The prickly shark Echinorhinus cookei, belonging to the Echinorhinidae family, is widely distributed in the temperate and tropical seas of the world, being registered in numerous countries of the American continent, both in the Caribbean and in the Pacific (Chirichigno,1963; Flores and Rojas, 1979; Bearéz, 1996; Robertson and Allen, 2002, 2015; Rojas et al., 2006; Mejía-Falla et al., 2007; Ruiz-Campos et al., 2010). The species is considered marine and pelagic, with coastal habits and a known distribution from shallow waters to 320 m depth (Rojas et al., 2006; Ruiz-Campos et al., 2010; Cortés et al., 2012). Echinorhinus cookei can reach 400 cm in total length (TL), its reproduction is of the aplacental viviparous type, and it is presumed that it feeds on a variety of fish, other sharks, octopuses, and squids (Cox and Francis, 1997; Brito, 2004).

This species has few records in the Eastern Pacific, from Oregon to southern Mexico, including the Gulf of California, El Salvador, and Costa Rica (Hubbs and Clark, 1945; Collyer, 1953; Ebert, 2003; Rojas et al., 2006; Ruiz-Campos et al., 2010). In South America, records are known from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador, Peru, and Chile (Chirichigno, 1963; Pequeño, 1989; Bearéz, 1996; Brito, 2004) with fragmented presence along the known distribution gradient and an unconfirmed report in Panama (Robertson and Allen, 2002, 2015). In the Colombian Pacific, it was considered a potential distribution species (Mejía-Falla et al., 2007; Mejía-Falla and Navia, 2019) despite having bibliographic records for the oceanic island of Malpelo (Rubio, 1988). However, to date, no specimens were available to corroborate its taxonomic identity.

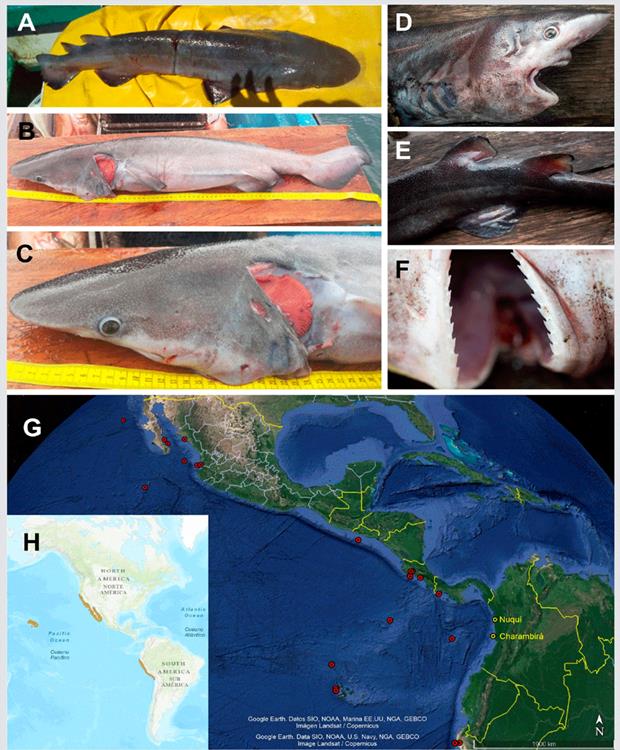

Since 2017, the Colombian national fisheries statistics system (SEPEC, for its acronym in Spanish) has been registering in localities such as Bahía Solano, Juradó, Tumaco, and Buenaventura, the landing of a shark species with the common name “tollo aguado” associated with artisanal fishing tasks and whose volumes were very low. In Colombian Pacific fisheries, this common name has traditionally been assigned to Prionace glauca, a very rare species in the area whose catches are restricted almost exclusively to the oceanic area and industrial fisheries (Mejía-Falla et al., 2017; Duarte et al., 2019). Since the so-called “tollo aguado” catches were concentrated in artisanal fisheries, it became evident that another species was being recorded under that common name. On March 10, 2021, during an artisanal fishing operation in Nuquí, Chocó (5°44’14.0”N, 77°16’36.5”W) at approximately 2 km from the coast and captured with a long line, a male specimen of 88 cm TL weighing 8 kg (Table 1) was captured at a depth close to 100 m. The external morphological characteristics of the individual were verified, and its identification as an Echinorhinus cookei specimen was confirmed (Figure 1B, C, Table 1). This individual (specimen 1) corresponds to an immature male (non-calcified clasper, 2 cm long). In this area, the species is used for bait and rarely for local consumption. Subsequently, on November 17, 2022, another “tollo aguado” individual (specimen 2) was captured in an artisanal long-line fishing operation at approximately 150 m depth. This capture was made in the vicinity of the community of Charambirá, Litoral del San Juan, Chocó (4° 14’ 08.5” N, 77° 35’ 59.8” W), about 8 km from the coast. This specimen corresponded to an immature female with a total length of 102 cm and a weight of 5.4 kg (Figure 1D-F, Table 1). Additionally, and based on photographs, it was possible to establish that in 2017, the capture of a specimen of this species was recorded in the vicinity of the Gulf of Tribugá, northern Chocó, and also in an artisanal fishing operation called “wind and tide” fishing (Figure 1A). Based on these specimens and their characteristics, it was established that the so-called “tollo aguado” caught in artisanal fisheries corresponds to the species E. cookei.

Table 1 Measurements of the captured Echinorhinus cookei specimens and their relation (in percentage) to the total length (TL).

Figure 1 Images of E. cookei specimens captured in 2017 (A), 2021 (B, C), and 2022 (D, E, F). Distribution map of confirmed occurrences in the ETP (red dots; taken from Robertson and Allen, 2015) and new records of the species in the Colombian Pacific coast (Nuquí and Charambirá; yellow dots) (G). Map of the extent of occurrence of E. cookei in the Eastern Pacific (taken from Finucci, 2018) (H).

Contrary to the landings obtained mainly in the south, the verifiable catches of this species (photos or specimens) in the Colombian Pacific are concentrated in the department of Chocó, where records of catches have occurred in the towns of Nuquí and Charambirá (this document) and Jurubirá (Malpelo Foundation, unpublished data). This species does not have a higher commercial value, its consumption is very occasional, and it is used more frequently as bait. Recently, using human-crewed vehicles, the presence of E. cookei was confirmed in the Colombian Pacific Ocean area, specifically on Malpelo Island, with an observation at a depth of 1,036 m (Bessudo et al., 2021).

Although the georeferenced records of the species in the Eastern Tropical Pacific (POT; Robertson and Allen, 2015) suggest that the species is rare and has a fractional distribution (Figure 1G), the increasing information about its capture in the Pacific coast of Colombia indicates a possible bias in previous knowledge about the distribution and abundance of this species (Figure 1H). This could be because the species inhabits very deep areas, and artisanal fisheries that overlap with its natural distribution do not catch it regularly. Moreover, when individuals of this species are caught, they are discarded as they lack commercial value. The current record complements the information on the latitudinal distribution of the species. It reinforces its continuous distribution throughout its latitudinal range in the Eastern Pacific and rules out a possible antitropical distribution (Figure 1H, taken from Finucci, 2018). This new information on its distribution in the POT will allow adjusting the values of the Extent of Occurrence and Area of Occupancy of the species for future evaluations of its threat category according to the IUCN criteria, where it is currently categorized as Data Deficient (Finucci, 2018).

text in

text in