CONTENTS

Introduction. 1. Literature on policing in Colombia. 2. Empirical notion of police legitimacy. 3. Research into police legitimacy. 4. Levels of police legitimacy in Colombia. 5. Research design, limitations and analytical strategy. 6. Results and discussion. Conclusions. References. Appendix A: Structure of the sample. Appendix B: Variables and measures. Appendix C: Regression outputs. Appendix D: Variables' codes.

INTRODUCTION

Fyodor Dostoevsky once said: "The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons"1. My interpretation of Dostoevsky's idea is that a real democracy must be strongly committed to human rights. This means that a democracy must protect everyone's rights regardless of who that person might be. Whether a person is a rapist, a murderer, a theft..., her human rights cannot be breached. As a result, these people whose behaviour makes them "undesirable individuals" are still entitled to enjoy human rights. Foucault gives an account of the disappearance of punishment as a spectacle by the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century, of the deprivation of its visible display and the transition to a stage in which punishment takes place under the secrecy of prisons2. In this scenario, where "undesirable individuals" are punished in a place and in a way that cannot be seen by members of the public, is when a democracy can be judged in its real dimensions. If prisons are places where inmates are treated with respect and dignity, a society can be regarded as civilised.

In a similar vein, the degree of civilization in a society can also be judged by assessing the police. A civilized society is one that engages with the notion of equity and democratic policing which assumes that "policing services should be distributed fairly between groups and individuals. When the police are enforcing the law, the pattern of enforcement should be fair and not targeted unjustifiably on particular individuals or groups"3. In contrast to this standpoint, the police usually target certain individuals and groups who are more likely to be policed4. This disproportionality might be due to the kind of crimes the police focus on which are more likely to be committed by the people who are usually policed, or the fact that these groups of people spend more time in public spaces, or their likelihood to fit stereotypes of suspiciousness or the less power they have to challenge police interventions5. Moreover, increasing anxieties, thanks to the sense of danger which is manipulated not only by the media but also by the state6, may lead people to accept and even desire this unjustifiable targeting on "dangerous others" just for the supposedly sake of security. This is precisely an uncivilised society and an undemocratic regime.

While hugely important, this is not, however, the only reason why policing must be a primary concern in a democracy. Weber argues that "coercion by violence is the monopoly of the state"7. In this way, the police are pivotal given that they have the power to exercise physical force which might be risky in terms of arbitrariness as discretion is an element essential to policing, given that "full implementation of the law is impossible, not only due to resources but because much of the daily routine of police work is not about law enforcement but service provision and order maintenance. As a result of this partial law enforcement compromise, police officers have the responsibility to decide who is arrested, stopped, questioned and so on"8.

Despite the relevance of the police in a democracy, policing has been understudied in Colombia. And among the scarce existing research on this topic, none has addressed police legitimacy, although the police are regarded by many citizens as the "face" of the state. In other words, the police can be considered as the most visible state institution due to the fact that they are the state on the streets, to borrow the telling title of Hinton's book9. There might be people who have never seen judges, legislators, ministers, presidents... but they have certainly encountered police officers. In consequence, the state should be interested in measuring police legitimacy, understanding what factors influence it and implementing procedures that help increase trust in the police.

Most of the empirical evidence suggests that there are at least two factors that are associated with police legitimacy10: People's assessment of the quality and style of police contact11, that is, the way the police treat them while being subject of an intervention (procedural justice), and strength of social order12, which is a broad term that encompasses a variety of elements from perceived police effectiveness in fighting crime, prompt response to calls for service, anxiety about crime, state legitimacy and discrimination to collective efficacy-community members' willingness to intervene in order to prevent and fight crime and disorder13-, racism, process of democracy, corruption and perceived social disorder14. In this respect, strength of social order as a foundation to police legitimacy could be regarded as a response to procedural justice theory's critics who consider that this interpretation of legitimacy cannot account for the episodes of police exercising their power in unfair ways that do not result in damage to legitimacy15. Thus, strength of social order is able to offer explanations for police legitimacy that procedural justice theory cannot.

As these associations that explain police legitimacy are yet to be tested in Colombia, this research presents a first attempt to overcome this lacuna and, drawing on secondary data from a survey conducted in Bogota, Cali and Medellin, the three main cities in Colombia, this paper seeks to answer the following research questions: Is there an association in Bogota, Cali and Medellin between perceived procedural justice during involuntary contacts of citizens with police officers, on the one hand, and police legitimacy, on the other hand? And is there an association in these three cities between strength of social order and police legitimacy?

For the purpose of this paper, police legitimacy, public trust and confidence in the police are interchangeable terms. Furthermore, it is crucial to distinguish between policing and police since they refer to different phenomena. Policing is "the set of activities aimed at preserving the security of a particular social order"16 and the police are an agent, among others, that do policing. Additionally, procedural justice refers to people's judgements about the fairness of the procedures whereby the police exercise their powers17. Another distinction that is worth making is that between low policing and high policing. While the former is defined as "everyday policing as performed by uniformed agents and detectives"18, the latter is identified in terms of political police whose aim is to protect the political regime, aim that encompasses the protection of the state, the national security, the nation's political institutions and the constitutional framework19. Given that the questions addressed in this article have to do mainly with involuntary contact with the police, which refers to street-level policing, this paper will focus on low policing. Lastly, in this paper proactive police contact with citizens, police-initiated contact and involuntary contact with the police are used interchangeably.

The article is organized as follows: in the next section, I review previous research on policing done in Colombia to show the level of development of the field where the present research is framed20. Following a brief discussion about the empirical notion of police legitimacy that this paper will embrace, I focus on the main findings of research into police legitimacy conducted in other countries. I then present some survey results on police legitimacy which provide some context about the importance of the issue that is going to be addressed. Next, I describe the research design, its strengths and weaknesses, and the analytical strategy I resorted to. The goal of such reflexive accounting is to give "a full explanation of the methodological procedures used to generate a set of findings, done in the interests of potential replications, and for the benefit of readers wishing to assess credibility"21. In the next section, I go on to present and discuss the results in light of previous research. Some conclusions are drawn in the remainder of the paper.

1. LITERATURE ON POLICING IN COLOMBIA

Robert Reiner agrees that the academic study of policing is relatively young, just about fifty years old22. Nevertheless, there is a vast literature on this topic, especially in the United States and the United Kingdom. By contrast, policing is not a field largely studied in Colombia, where the police are only trusted by roughly half of the population, in line with some surveys shown below. This lack of studies is surprising since crime rates in Colombia are very high-this country has a homicide rate slightly less than double the regional average in the Americas (30.8 versus 16.3 per 100,000 population), according to data of 2012 published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime23, picture that has hardly changed over time-and police work is usually linked to crime control, although this image has been challenged by empirical evidence: "The police are as much a social service agency as they are a crime fighting outfit"24. Popular images suggest that the main task of the police is dealing with crime in spite of the fact that sociological research in the United States and the United Kingdom has concluded that the bulk of police work involves tasks other than crime control25.

Literature on policing can be framed within four waves of research. The first wave relates to the study of police misbehaviour. As stated by Punch, the emphasis "tended to be on investigation of abuses and on deviations from the legally prescribed norms of law-enforcement"26. The second wave of research rests on the effectiveness of policing, "defined in terms of impact of these policies and practices in identifying those whose behaviour may signal that they are intending to commit serious crime, or that they may have just completed a crime [...]. The standard inquiry in this type of evaluation is whether stops turn up active offenders or those being sought by the police or the seizure of contraband"27. A third wave of research lies in police cultures. That is, the study of the institution from inside, focusing on "police work as work"28. The aim of this set of studies, which mainly relies on ethnographies and participant observations, is to understand workplace practices and attitudes by describing "the minutiae of officers' daily shift work and lives"29. A fourth wave of research into policing concentrates on police legitimacy and on "how the activities of the police shape public views about police legitimacy"30.

I now resort to this framework to critically review the existing literature in Colombia while showing its weaknesses, not as a critique but as a way to better interpret research findings. Although there are books and articles on policing besides those cited in this paper, they are solely theoretical. The ones reviewed in this section are the only ones, to my knowledge, that have attempted to answer research questions with empirical evidence.

Police misbehaviour

In regard to police misbehaviour, it must be acknowledged that the media has hugely reported police abuses and misconduct, yet there are only four pieces of research that have addressed this issue in Colombia. The think tank CINEP gathers data of human rights violations in Colombia and publish it periodically in the journal Noche y Niebla. In one of the latest issue, CINEP stated that during 2016 the police were the presumed responsible for 548 human rights violations31. To get a sense of the magnitude of this matter, the paramilitary groups were the presumed responsible for 550 human rights violations in 2016. That is to say that illegal armies committed two more human rights violations in 2016 than a legal force which is supposedly in charge of security and human rights protection. While shocking, the reliability of this data could be questioned on the grounds that its sources were the victims, their families and counsels rather than independent agencies that provided information after carefully investigating each case.

Coupled with this journal, a research project on protests and riots provided evidence of misbehaviour by Colombian police riot squad that led to multiple injuries and fatalities32. For instance, it documented cases where the riot squad used firearms, which is not allowed, and killed people involved in protests. This study relied on interviews with police officers and people who usually exercise the right to protest. It also reported both judicial decisions whereby riot squad officers were found guilty of malpractice and media reports about police abuses.

Elsewhere I analysed data drawn from the same survey explored in this paper that demonstrated that certain people are more likely to be stopped and searched33. The main findings of this piece of research suggested that proactive police contact with citizens was more likely to target men, people from working and middle class, black and indigenous people and individuals that had or wore either visible tattoos, visible scars, baggy shirts, baggy trousers, baggy caps, shorts, skinny trousers, uncommon haircuts, dark clothes or dirty clothes. These conclusions were also supported by borrowed interview data from previous unpublished empirical work. A critical assessment of this piece must take into account that the sample was not truly representative of people who live in the three cities where the survey was done because its respondents were not chosen at random from the population34, although weighted data was used in the analysis to correct for the imbalance in the sample.

Using qualitative data collected in Cali, a city where more than half of its population is black and where they are heavily discriminated against, and building on interviews with black people, Lam and Ávila-Ceballos described several cases in which the police mistreated black citizens35. Since the information given by the interviewees was not contrasted with other sources of data before making inferences, it is not clear whether their accounts were exaggerated and led researchers to commit what Jerolmack and Khan call the attitudinal fallacy, that is, "the error of inferring situated behaviour from verbal accounts"36.

Policing effectiveness

In relation to effectiveness of policing, there are two pieces that attempted to assess the impact of hot spot policing. Ramírez evaluated hot spot policing in Bogota between the years 2009 and 2011 and concluded, by analysing the crime in two areas of the city where this strategy was implemented, that it was not effective in reducing crime37. However, this piece of research is problematic in the sense that it relied on data about reported crimes rather than on victimisation rates. In this context, the rise of some crimes after the implementation of the policy might have been due to an increase in crime reporting rather than to an actual growth of victimisation.

Along with this preliminary effort to examine the effectiveness of hot spot policing in Bogota, Ruiz-Vásquez and Páez maintained that hot spot policing in Bogota and Medellin from 2008 to 2016 had positive results in decreasing some crimes in certain areas where this strategy was applied38. They also pointed out that there were unintended consequences such as the displacement of crime. This work, however, was not a proper impact assessment since it did not collect independent and reliable data. The authors simply reproduced information on crime reporting provided by local governments-not by an independent entity with no interest in hiding information-rather than data on victimisation rates. This data might be therefore untrustworthy as there is evidence that the police in countries such as England, Wales, France and Australia have manipulated crime statistics39. The other source employed by Ruiz-Vásquez and Páez was media reports in which neighbours who were interviewed stated that crimes had displaced. In this scenario, evidence of crime displacement was weak since it was based on perceptions rather than on actual experience of displacement.

Police cultures

When it comes to police cultures, literature is even fewer. Some colleagues and I examined a programme implemented in Bogota and Soacha in 2015 where some police officers were trained to mediate disputes between citizens40. To that end, we did both non-participant observations and interviews with police officers and citizens whose conflicts were mediated by the police. The data collected revealed sexist and racist cultures within the police force that had an important effect on the way officers approached disputes that involved women, black people and members of the LGTB community.

Thanks to fieldwork I have done when doing research into policing in Bogota, I observed that police chiefs regularly demanded on each shift that constables asked a given number of people for identification, arrest certain number of individuals, seize a given amount of knives, among other requests. This pressure often led officers to arbitrary actions such as arresting innocent people and buying the knives that were not found during searches41. This evidence was drawn from interviews with 30 constables in Bogota that agreed that this situation in effect happens, which shows that saturation was attained and therefore generalisation could be claimed at least in Bogota and in the squads in which these officers worked42.

If policing in general has not been studied that much in Colombia besides this handful of pieces of research, police legitimacy has been totally ignored. Unlike other countries, where the variables that have an effect on shaping police legitimacy have been largely studied, literature in Colombia has not focus on this matter at all.

Overall, evidence-based policymaking on policing in Colombia is very unusual. The present research falls within this framework and intends to provide empirical evidence of factors that may explain the levels of public trust in the police in Colombia, which in turn could be useful for policymakers to design evidence-based policies.

2. EMPIRICAL NOTION OF POLICE LEGITIMACY

Probably one of the most well-known definitions of legitimacy is the one provided by Weber, who links it to the term domination. For him, domination is "the probability that certain specific commands (or all commands) will be obeyed by a given group of persons"43. According to this thinker, there are three pure types of legitimate domination depending on the grounds the claims to legitimacy are based on. The claims may be based on rational grounds, that is, "a belief in the legality of enacted rules and the right of those elevated to authority under such rules to issue commands (legal authority)"44; on traditional grounds, that is, "an established belief in the sanctity of immemorial traditions and the legitimacy of those exercising authority under them (traditional authority)"45; and on charismatic grounds, that is, the "devotion to the exceptional sanctity, heroism or exemplary character of an individual person, and of the normative patterns or order revealed or ordained by him (charismatic authority)"46.

In a democracy governed by the rule of law, which is the case of Colombia, police domination should be anchored to their legal authority. Yet, this is an objective or normative conceptualisation of legitimacy that overlooks a subjective or empirical notion of legitimacy47. When legitimacy is examined from an empirical perspective, studies have shown that citizens consider the police to be legitimate and to have the right to ask them to obey because of a number of factors other than their legality48. Therefore, the main difference between the normative and the empirical conceptualisation of legitimacy rests on the source of domination. While the source of the normative notion is the legality of the police, the source of the empirical notion is people's assessment on the way the police exercise their powers, that is, procedural justice, and strength of social order49. Empirical research has also demonstrated that procedural justice and strength of social order-not police legality-have the potentiality to trigger some behaviours like law-abidingness and cooperation with the police50.

Thus, the Weberian conceptualisation of legitimacy, which relies merely on police legality, seems fairly narrow when it comes to exploring public trust in the police from an empirical standpoint which is the goal of this article. I am not arguing, of course, that legality is not important. On the contrary, legality is central, particularly in Colombia where there is qualitative evidence that suggests that illegal armies, such as right-wing paramilitary groups and left-wing guerrillas, have de facto performed tasks that the police are in charged with such as maintenance of order, control of disorder and prevention of crime51.

As a result, the Weberian approach should be regarded as necessary, yet not sufficient. It must, therefore, be complemented with an empirical concept of legitimacy that provides evidence of why there are people who do not trust the police, despite the fact that they are a legal authority. Police legitimacy is then understood is this paper as a concept that have to go beyond the notion of legal authority (normative legitimacy).

3. RESEARCH INTO POLICE LEGITIMACY

As seen above, among the four waves of research into policing, the wave that has been the most neglected in Colombia is the one that focuses on police legitimacy. Neither academics nor the government have attempted to explain why some people trust the police, while some do not. Fortunately, this conundrum has been faced by studies carried out elsewhere which provide compelling evidence suggesting that police legitimacy is associated both with procedural justice and strength of social order. This huge body of empirical literature reveals that improvements in police legitimacy can bring about more law-abidingness and more public willingness to cooperate with the police.

Based on results of a cross-sectional national survey conducted in the United States in 2012 using a probability sample of 1,603 individuals aged 18 and over, Tyler et al. found that respondents who lived in neighbourhoods where disorder was a problem were more likely to distrust the police52. This finding could demonstrate that legitimacy is shaped by the strength of social order. Nevertheless, these authors also found that police legitimacy was not associated with fear of crime, which could partly challenge the strength of social order approach in this respect. Interestingly, this study demonstrated that police legitimacy was associated with willingness to cooperate. Accordingly, those who considered the police to be legitimate were more likely to report crimes and help to prosecute criminals53. It is crucial to recognise that the questionnaire asked respondents on likelihood of cooperation with the police, rather than on actual experiences of cooperation.

Tyler et al. analysed the results of telephone interviews with a stratified random sample of 1,261 men aged 18-26 in New York City in 2012. Their main findings were four. First, people who experienced a personal contact with the police and who felt that they had not been fairly treated were less likely to trust the police54. Second, people who perceived that the police treatment of citizens in their neighbourhood was fair were more likely to regard the police to be legitimate55. Third, legitimacy promoted cooperation with the police and people who thought that police stop and searches in their neighbourhood were intrusive were less likely to cooperate56. Four, high scores for police legitimacy were associated with less engagement in criminal activity in the past year57.

As some of these results were based on perceptions and not on actual contacts with the police where intrusiveness was directly experienced by respondents, Harkin's critique is relevant in the sense that these people's perspective on the police could have been born in a hypothetical image of them where ideology and backgrounds could have played a vital role: "The more participants could not justify their relationship to the police in terms of actual, lived experience, the more important it becomes to consider abstract ideological issues. Such ideological knowledge fills the vacuum left by a scarcity of first-hand proof and experience"58. This author cited the example of immigrants who may "import their views on police legitimacy from their home-of-origin. Such views do not reflect in any way on the behaviour of the local police, but the local police can be subject to a legitimacy deficit because of those views"59. Furthermore, the finding related to law-abidingness was problematic because it depended on a self-report measure which can lead to social desirability biases. Additionally, the directionality was uncertain: police legitimacy could have had an effect on law-abidingness or, conversely, engagement in criminal activity might have had an effect on lack of confidence in the police.

The association between procedural justice and law-abidingness was confirmed by an experimental study that overcome the limitations of the survey methodology highlighted above. Unlike previous research that had assessed the association between procedural justice and attitudes about legitimacy, and between procedural justice and subsequent self-reported offences60, an experimental study undertaken in Milwaukee in the late 1980s revealed that the use of fair procedures by the police when arresting spouse assault suspects inhibited subsequent assault in a greater degree than when procedural justice was not employed. For this experiment, 825 male suspects arrested were interviewed on whether they believed they had been treated in a procedurally fair way and reoffending rates were drawn from public records. Paternoster et al. argued that the reason why procedural justice led to more law-abiding people is that it made spouse assault suspects "feel attached to the social order"61 and certified "their full and valued membership in the group"62.

This experiment was eloquent in describing the link between procedural justice and propensities to comply with the law in the future, but it had at least three relevant limitations. First, as it took place in the suspects' environment, there may be confounders. Second, suspects arrested were not randomly assigned to officers who respected procedural justice and who did not. In this context, the most aggressive and violent suspects, who might have been likely to reoffend due to those characteristics, could have been mistreated by the police officers as a consequence of their disrespectfulness. Third, the suspects were interviewed while in police custody, which could have led to social desirability bias. These limitations, therefore, prevented causality claims.

The Milwaukee Domestic Violence Experiment was challenged, however, by a randomised controlled trial conducted in 2013 in Scotland with 816 drivers who were stopped by the police. This research did not find any statistically significant effect on trust in the police as a consequence of procedural justice. People in the treatment group as well as people in the control group reported high levels of confidence in the police63. This may have been due either to the lack of association between procedural justice and police legitimacy or to the limitations of the study. Researchers acknowledged that preliminary qualitative fieldwork had revealed that regular and day-to-day interactions between the police and drivers had many procedural justice features incorporated64. Given that officers in the treatment group and in the control group were told to act as usual, the real difference then was that drivers in the treatment group were given a leaflet which explained that the police had the right motives in conducting the stop. Since such leaflet was the intervention, what the results of this experiment actually showed is that the leaflet, as a way to add something additional and to the procedural justice already perceived by drivers, had no impact on enhancing police legitimacy. Moreover, all drivers stopped were given a questionnaire and asked to send it by post or, alternatively, to respond to it online. Therefore, those who did respond to the questionnaire could have been more likely to regard the police to be legitimate, which may explain why no differences were found between treatment and control group.

It is worth noting that the bulk of research into police legitimacy has been carried out in the United States and the United Kingdom65. The question that raises is whether these findings would be similar in other countries, especially in developing countries with high crime rates and whose societies are socially divided and very unequal, which is the case of Colombia. Tankebe addressed this issue in Ghana. He analysed a cross-sectional survey conducted in 2006 in Accra which used a multistage sample of 374 individuals aged 18 years and older66. Tankebe found that procedural justice and police trustworthiness were positively correlated with public willingness to cooperate with the police67. He also observed a positive correlation between procedural fairness and police trustworthiness68. But more interesting, cooperation was found to be associated with perceptions of police effectiveness69. For him, since Ghana failed to establish a clear distinction between colonial and postcolonial legal authorities, people may have identified the police and their procedures with colonial policing, therefore they may have decided to cooperate with them only if they felt that security would have been enhanced70. One limitation that is worth mentioning is that not all the research participants had a direct encounter with the police71, hence there could have been differences between people who actually experienced procedural justice and people who perceived procedural justice.

In line with this evidence, Bradford et al., drawing on the 2010 round of the South African Social Attitudes Survey, an annual national survey with a nationally representative probability sample of 3,183 South African adults aged 16 years and over, offered robust evidence that police effectiveness constituted a stronger predictor of police legitimacy than procedural justice72. Bradford et al. argued that this result may have been due to the growing existence of private security and vigilante groups73. As people may turn to alternative security providers, assessments of police effectiveness might have played a key role. Moreover, the authors posited that there were wider social and political factors that shaped police legitimacy. For instance, they provided evidence that perceptions of corruption, experience of victimisation and fear of crime undermined police legitimacy, while trust in the government in a wider sense was likely to improve trust in the police (i.e. satisfaction with basic service provision was associated with police legitimacy)74.

Finally, García-Sánchez et al., drawing on the Americas Barometer survey of 2014, indicated that in the American countries people who felt unsafe in their neighbourhoods were less likely to trust the police, probably because they regarded that situation as a failure of police effectiveness75.

This is not to say that police legitimacy in the United States and the United Kingdom is not shaped by public assessments of police performance and effectiveness. Tyler holds that evidence from Anglo-American studies points out that public views about police legitimacy could be influenced by these variables. Although research has indicated that people are more likely to refer to procedural-justice issues than to performance or effectiveness of the police when making inferences about police legitimacy76.

In summary, research has demonstrated that procedural justice influences people's behaviours in relation to law and the police. Thus, people who are treated by the police respectfully and fairly are more likely to regard this institution to be legitimate, which means that they are in turn more likely to cooperate with them and to obey the law. Other set of studies in the United States and the United Kingdom has stated that police legitimacy is linked to perceived police effectiveness, but this association is less strong than the association between procedural justice and police legitimacy77. However, these findings have been challenged by research done in more unequal societies with higher crime rates. In these settings, perceived police effectiveness is a stronger predictor of police legitimacy and public cooperation with them than procedural justice78. Overall, the studies reviewed are consistent with each other. Of course they all have different limitations, but the fact that their results point in the same direction, regardless of the methodology employed, means that this body of literature offers robust evidence of the association between procedural justice and willingness to cooperate with the police and comply with the law, on the one hand, and between strength of social order and cooperation, on the other hand.

4. LEVELS OF POLICE LEGITIMACY IN COLOMBIA

I argue that police legitimacy in Colombia is low-which could have negative effects upon law-abidingness and cooperation with the police, according to the literature reviewed above-because it is usually lower than trust in the army which is probably the state institution that citizens would be more likely to relate to the police despite being forces in charge of different duties79. In this context, having a look at trust in the army while analysing trust in the police could shed light on how low the police legitimacy in Colombia is.

The survey Encuesta de percepción y victimización conducted by Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá80 between June and August 2017, which used a probability sample of 8,749 inhabitants of Bogota aged 18 and over and face-to-face interviews, revealed that 45 percent of the people surveyed considered that the work carried out by the police when it comes to security issues was poor and 33 percent thought it was fair, while 23 percent of the individuals deemed the work of the police as good. By contrast, the work carried out by the army was considered to be good by 55 percent of the people surveyed.

Results of one of the latest Gallup Poll conducted in June and July 2018 in Bogota, Medellin, Cali, Barranquilla and Bucaramanga, which consisted of 1,200 telephone surveys of residents of those cities aged 18 and over, showed that 54 percent of the people surveyed had a positive opinion about the police and 44 percent had a negative opinion about them, whereas 75 percent had a positive opinion and 22 percent had a negative opinion about the army81.

According to one of the latest Americas Barometer surveys done by the Latin American Public Opinion (LAPOP), which used a national probability sample design of 1,512 Colombian voting-age adults, 49 percent of the people surveyed in 2014 trusted the police while 59 percent trusted the army82.

On the other hand, cross-country comparisons are also possible with data drawn from the Americas Barometer survey conducted in 2014 and analysed by García-Sánchez et al. This survey was done in 28 countries, it was nationally representative of voting age adults in each country and it was weighted so that each country had an identical weight in the pooled sample83. According to the Americas Barometer survey, police legitimacy in Colombia in 2014 was not as low as it was in other countries such as Guyana, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic and Bolivia where public confidence in the police was roughly 13 percentage points lower than it was in Colombia, as shown in Figure 1. Nevertheless, when compared to countries with a more robust and stronger democracy, police legitimacy in Colombia can be regarded as low. The Rule of Law Index measures countries' adherence to the rule of law through "the experiences and perceptions of ordinary citizens and in-country professionals concerning the performance of the state and its agents and the actual operation of the legal framework in their country". To this end, the World Justice Project regularly conducts general population polls as well as a series of qualified respondents' questionnaires. According to the Rule of Law Index, Canada is ranked 9th in the global ranking; Chile, 27th; and Colombia, 72nd84. In this scenario, police legitimacy in Canada and Chile in 2014 was nearly 18 percentage points and 15 percentage points higher than it was in Colombia, respectively (Figure 1).

Source: GARCÍA-SÁNCHEZ, M., RODRÍGUEZ-RAGA, J. C., SELIGSON, M. A. & ZECHMEISTER, E. J. Cultura política de la democracia en Colombia, 2014. Dilemas de la democracia y desconfianza institucional en el marco del proceso de paz. Bogotá: USAID, 2015, 112.

FIGURE 1 TRUST IN THE POLICE IN AMERICAN COUNTRIES

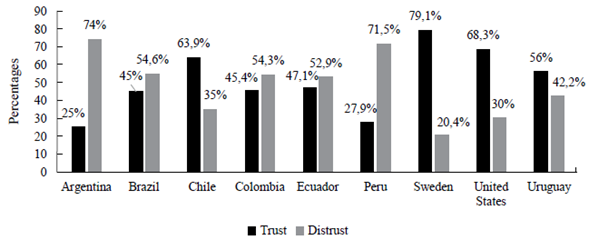

Another source of data useful to examine how high or low police legitimacy is in Colombia when compared to other countries is the World Values Survey which was a poll that was representative of people aged 18 and over in each country where it was carried out. One limitation of this survey was that it was only conducted in some cities of each country, therefore it was not representative of the population of the entire country. I focus on the South American countries where the survey was conducted to frame the Colombian case in a regional context. The South Americans countries where the survey was done are Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Uruguay. The questionnaire applied asked for how much confidence the interviewee had in the police and the answer had four options: a great deal of confidence, quite a lot of confidence, not very much confidence or none at all. In order to make this analysis simpler I cluster the first two options and consider them as trust in the police and then I cluster the remaining two and consider them as distrust.

Figure 2 indicates that the most common trend in South America was distrust of the police, as opposed to trust. This is the case of Argentina where 74 percent of the people surveyed distrusted the police, Brazil where 55 percent distrusted the police, Colombia where 54 percent distrusted the police, Ecuador where 53 percent distrusted the police and Peru where 72 percent distrusted the police. Interestingly, Uruguay and Chile did not follow this trend. In these countries the majority of the people surveyed trusted the police. Thus Colombia had a level of trust in the police which did not seem rare in the South American context. It is noteworthy that trust in the police in Colombia was even a lot higher than it was in Peru and Argentina. However, police legitimacy in Colombia was very low when compared to developed countries such as Sweden, as seen in Figure 2.

Source: WORLD VALUES SURVEY. World Values Survey Wave 6:2010-2014. 2014. Selected samples: Argentina 2013, Brazil 2014, Colombia 2012, Chile 2012, Ecuador 2013, Peru 2012, Sweden 2011, United States 2011, Uruguay 2011. Year differences are due to the fact that the survey was not carried out at the same time in every country.

FIGURE 2 TRUST IN THE POLICE

In sum, levels of confidence in the police in Colombia varies according to the surveys analysed, which is normal due to differences in sample designs and in questionnaires. In addition to this, assessments of police legitimacy are made at a particular time and this is a fluid notion, as stated by Bradford et al., in the sense that these valuations "may change over time or vary depending on context. People may assign the police more or less legitimacy in different places or at different times"85.Yet, broadly speaking and considering the limitations of the surveys and the comparisons, around 40 and 50 percent of the people surveyed trusted the police. This level of public confidence in the police seems to be low, at least when compared with public confidence in the army. However, levels of trust in the police in Colombia could be regarded as acceptable in the American context. Nevertheless, the fact that trust in the police was higher in some South American countries as well as in developed countries indicates that this state of affairs must not be seen as inevitable. It is then possible to achieve improvements in this matter. To this end, it is necessary to identify why a large proportion of the population in Colombia-nearly half of it-did not trust the police which is my goal in the remainder of this paper.

5. RESEARCH DESIGN, LIMITATIONS AND ANALYTICAL STRATEGY

Methodology

This study drew on secondary and pooled data gathered by a survey conducted in 2013 in Bogota, Medellin and Cali. This survey was designed by a Colombian think tank named Dejusticia. Although the raw data is unpublished, I was allowed by Dejusticia to use it in this article.

As my aim was to explore probabilistic associations between some variables of interest, survey methodology was an appropriate methodological choice86. Naturally, this methodology has limitations. Thus, my exercise shows, at best, associations, as opposed to experimental methodologies which may show causality and directionality87. Nevertheless, I claim directionality in this paper from a theoretical perspective and based on previous research. Equally, survey methodology has the weakness of being unable to provide full certainty that the associations found are real and not affected by confounding variables.

Sampling process

This cross-sectional survey was based on a convenience sampling of 2,146 respondents. Between May 25th and June 10th of 2013, 844 people were surveyed in Bogota; 649, in Cali; and 653, in Medellin (the sample structure is summarised in Appendix A). All the interviews were conducted face-to-face by an interviewer on a street corner and, to control selection biases, interviewers were required to survey alternately one woman and one man, and to survey people with different physical appearance and from different social classes. To this end, surveys were carried out in public places where people from all these backgrounds and with these characteristics are expected to be such as football grounds, courthouses, public libraries and shopping centres. Thus, the sample excluded institutionalised population, that is, people living in hospitals, prisons and other institutions88. It is important to recognise this limitation because in those settings, especially in the most coercive ones, like prisons, police legitimacy could be low as many inmates might have been put in jail thanks to the work of the police as they are "the normal gateway to the criminal justice process", as expressed by Reiner89.

Since convenience sampling is a type of nonprobability sampling, representativeness is not one of its features. There is risk of bias, therefore extrapolations and generalisations to general population cannot be made90. This is explained by the fact that in this kind of surveys interviewers are "most likely to approach people who look approachable and are obviously not in a great hurry to be somewhere else"91. Notwithstanding this weakness, such technique has a feature that makes it the most appropriate one for the purpose of a study of this kind. Physical appearance is one of the factors people usually use to discriminate against others92. In addition to this, there is evidence in Colombia suggesting that youth styles and subcultures93, from rappers to punks, determine partly who is policed against94. Since one of my aims was to explore the association between police legitimacy and procedural justice, physical appearance could make a difference because the police may mistreat those individuals as a result of prejudices and, therefore, they might not consider the police to be legitimate. From this perspective, it was key to include in the sample people with different physical appearances, which would not be secured by probability sampling due to the lack of a sampling frame from which the sample could be selected.

Owing to limited space, I did not test here whether the associations hypothesised maintain controlling for the demographic data available, including physical appearance. The influence of race, gender, age, social class and physical appearance on police legitimacy in Colombia is likely to be a complex subject which is beyond the scope of this paper.

Questionnaire

The primary aim of the survey was to collect data on public safety and discrimination in policing. Accordingly, the questionnaire included demographic questions (age, social class, gender, race, educational attainment), questions on public safety (anxieties, assessment of state institutions tasked with issues in relation to security), questions on victimisation (crime reporting, public-initiated contacts with the police to report dangerous or suspicious activities or report a crime) and questions on policing (proactive police contacts, police treatment).

One strength of the questionnaire was that it minimised the recall period. Every time it asked respondents whether or not they had experienced certain situations, such as being victimised or having involuntary contacts with the police, the questions were limited to those experiences that had occurred in the past year. In this way, the risk of memory bias was reduced.

Another advantage of the questionnaire is that it asked about actual experiences of public-initiated contacts with the police and proactive contacts, rather than perceived likelihood of initiating voluntary contact with the police in the future or perceived likelihood of being policed against. Hence, the weakness of Tyler et al.'s study mentioned above, whose questionnaire relied on likelihoods and perceptions rather than on experiences, could be overcome95. As Jerolmack and Khan put it, "psychological research on attitude-behaviour consistency (ABC) has repeatedly demonstrated that people's verbal responses at time 1 are often unrelated to their observed behaviour at time 2"96.

Interestingly, at the end of the survey the interviewers were required to record respondent's physical appearance using a checklist and without asking the person surveyed. The checklist comprised: baggy shirt, baggy cap, baggy trousers, shorts, skinny trousers, unusual haircut, dark clothes, dirtiness, visible scars and visible tattoos. While it is true that respondent's physical appearance was subjectively determined by the interviewers, which could be regarded as a weakness of the questionnaire, this is probably the best and fastest way to determine someone's physical appearance. Self-reporting was not an alternative because, when it comes to discrimination, what matters is how people are perceived and seen by others who discriminate on those bases, rather than how the people discriminated against see themselves.

Hypotheses

The hypotheses addressed in this paper were six. The first four tested the procedural justice theory in Bogota, Medellin and Cali, and the remaining two tested the strength of social order model in the same three cities.

* The procedural justice theory suggests that perceived procedural fairness increases police legitimacy.

1. People who considered that their rights were respected when experiencing involuntary contacts with the police are expected to be more likely to report the crimes they are victims of.

2. People who believed that their rights were respected when experiencing involuntary contacts with the police are expected to be more likely to initiate voluntary contacts with the police in order to report dangerous or suspicious activities or report a crime.

3. People who considered that their rights were respected when experiencing involuntary contacts with the police are expected to be more likely to assess the police services during public-initiated contacts either as good or very good.

4. People who claimed that their rights were respected when experiencing involuntary contacts with the police are expected to be more likely to evaluate police effectiveness in controlling crime as good.

* The strength of social order approach claims that perceived police effectiveness increases police legitimacy.

5. People who felt safe in their neighbourhoods are expected to be more likely to report the crimes they are victims of.

6. People who perceived police effectiveness to be good are expected to be more likely to report crimes they are victims of.

Variables

The response variable in these six hypotheses was police legitimacy, concept that researchers have usually operationalised as people's perceived obligation to obey the police, public trust and confidence in the police97 and moral alignment with the police98. The use of this definition has led researchers to link police legitimacy to a variety of behaviours, such as crime reporting, public-initiated contacts, assessment of police services during public-initiated contacts and evaluation of police effectiveness in controlling crime. These behaviours could be then used as proxies for police legitimacy since none of the questions in the survey analysed here asked respondents on perceived obligation to obey, on trust nor on moral alignment.

Empirical evidence has demonstrated that public confidence in the police is associated with people's willingness to cooperate with them99. In other words, citizens who support the police are likely to consider them to be legitimate. As Tyler points out, "The public supports the police by helping to identify criminals and by reporting crimes. In addition, members of the public help the police by joining together in informal efforts to combat crime and address community problems, whether it is by working in 'neighbourhood watch' organizations or by attending community-police meetings"100. In this light, it is reasonable to think that people who report the crimes they are victims of and people who voluntarily initiate a contact with the police are citizens who trust them. Therefore, I used in this paper crime reporting as well as public-initiated contacts as proxies for police legitimacy.

In addition to the above, the survey had two more questions that were connected to police legitimacy. First, respondents who had a voluntary citizen-initiated contact with the police were asked to assess police services. Second, people surveyed were asked to assess police effectiveness in controlling crime. Studies have observed that assessment of police performance and effectiveness are associated with public trust in the police101. In this view, I presumed that public evaluations of both police services during public-initiated contacts and police effectiveness in controlling crime were pieces of information about citizens' perceptions of trust in the police. Thus, I used these variables as proxies for police legitimacy.

The explanatory variables in the hypotheses formulated, for their part, were procedural justice and strength of social order. The survey asked those respondents who had involuntary contacts with the police if during that interaction their rights were respected. Tyler reviews some studies that have identified what criteria are taken into account by people when evaluating a procedure's fairness102. One of those key elements that people value is being treated with dignity and respect103. Therefore, I assumed that perceived respect for the rights of the person being policed could be taken as a proxy for procedural justice. Likewise, some pieces of research have found associations between strength of social order and public trust in the police through perceptions of safety in the neighbourhoods where people live in104 and perceptions of police effectiveness105. Given that the survey asked respondents whether they felt safe or unsafe in their neighbourhoods and required them to evaluate police effectiveness in controlling crime, I used these two variables as proxies for strength of social order. As a result of the literature cited, the methodological decision of taking these variables as proxies for police legitimacy, procedural justice and strength of social order is not arbitrary (Appendix B shows the wording of the questions used to generate the variables).

Analytical strategy

As the hypotheses formulated in this paper looked for associations among variables, regression analysis was the appropriate analytical strategy to employ. Furthermore, the regression model I used was a binary one, especially a logistic regression model, since my response variables were categorical and dichotomous106. The way the variables were coded to fit the regression model can be seen in Appendix D.

It is noteworthy that the number of respondents varied depending on the hypothesis due to filter questions included in the questionnaire. While it is true that the sample was comprised of 2,146 respondents, not all of them answered every single question given that the questionnaire was designed in a way that some questions were only asked to people who agreed with a previous question. For instance, only the respondents who experienced involuntary contacts with the police were asked if they believed that their rights were respected during the contacts and only the ones who were victimised were asked whether or not they reported the crime. So that, the subsample used to test hypothesis 1 consisted of those respondents who were victimised and who also experienced proactive contacts with the police. The size of the subsamples considered when testing each hypothesis can be seen in Table 1.

TABLE 1 SIZE OF THE SUBSAMPLES

| Hypothesis 1 | Hypothesis 2 | Hypothesis 3 | Hypothesis 4 | Hypothesis 5 | Hypothesis 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 194 | 539 | 138 | 537 | 492 | 492 |

All models were estimated using both coefficients scales in log odds and odds ratios, which are different ways to express exactly the same issue107. However, odds ratios could be easier to interpret. In consequence, the evidence provided here was interpreted in terms of odds ratios.

6. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

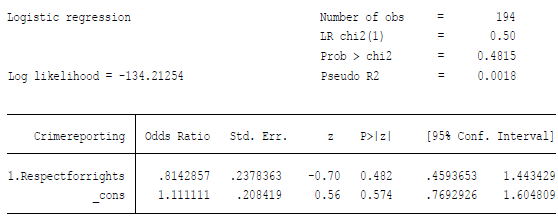

In this paper, procedural justice was measured as the level of respect the police had for respondents' rights during involuntary encounters and police legitimacy was measured in a variety of ways. First, crime reporting was used as a proxy for police legitimacy and was modelled alongside procedural justice. Unlike Tyler el al., who observed a correlation between police legitimacy and willingness to report a crime in the United States108, no evidence in favour of this hypothesis was found here (regression outputs can be seen in Appendix C). However, there is a slight difference between both studies. While this paper concentrated on actual crime reporting, Tyler et al.'s focused on willingness to report a crime.

Perhaps perceived fairness during contacts with the police does improve police legitimacy in Colombia, thereby it raises crime reporting rates. Yet, many respondents could have experienced involuntary encounters with the police after-not before-being victimised, something the design of the questionnaire did not allow me to control for. Another alternative is that crime reporting in Colombia is a behaviour associated with instrumental reasons, rather than with legitimacy reasons. According to a survey on unmet legal needs conducted in 14 main cities in Colombia in 2013, which was representative of people aged 18 and over, only 4.6 percent of respondents who had a legal need, including having been victimised, and who did not take any actions in order to solve the problem claimed that they made that decision based on the lack of confidence in the authorities. The majority did not take any actions to solve the problem because it was not worth it (27.3 percent) or because it was very time-consuming (20.3 percent)109.

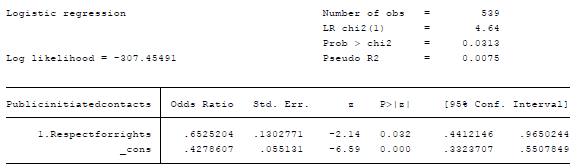

Nevertheless, when police legitimacy was measured as public-initiated contacts with the police to report dangerous or suspicious activities or report a crime, the data did show an association between procedural justice and police legitimacy (p<0.05). Surprisingly, for respondents who considered that their rights were respected during a proactive encounter with the police, the odds of initiating voluntary contact with them either to report dangerous or suspicious activities or report a crime decreased in relation to the odds for respondents who did not find that their rights were respected (Table 2). In contrast to the hypothesis formulated and to some studies conducted in the United States and Ghana110, procedural justice did not seem to enhance police legitimacy, at least when the variable public-initiated contacts to report dangerous or suspicious activities or report a crime was used as a proxy for police legitimacy. One possibility is that, despite regarding the police to be legitimate thanks to procedural justice, respondents did not report having initiated a voluntary contact simply because they were not aware of any dangerous or suspicious activities or because they had not been victimised. This could be the case because, when running the same regression controlling for victimisation, the association does not maintain.

TABLE 2 LOGISTIC REGRESSION FOR PUBLIC-INITIATED CONTACTS

| Odds ratio | Standard error | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for rights | 0.652 | 0.130 | 0.032 |

| Constant | 0.428 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.007 |

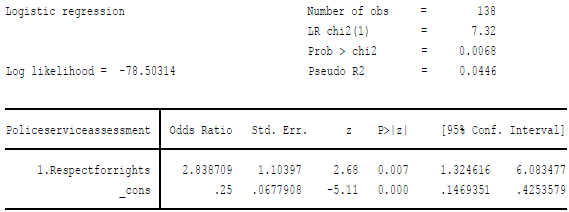

Additionally, the data showed another association between procedural justice and police legitimacy when measured as assessment of police services during public-initiated contacts (p<0.01). As hypothesised, the odds that respondents who considered that their rights were respected during a proactive encounter with the police and evaluated their services during public-initiated contacts either as good or very good were 2.839 times larger than the odds for those who claimed that their rights were not respected (Table 3).

TABLE 3 LOGISTIC REGRESSION FOR ASSESSMENT OF POLICE SERVICES DURING PUBLIC-INITIATED CONTACTS AS GOOD OR VERY GOOD

| Odds ratio | Standard error | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for rights | 2.839 | 1.104 | 0.007 |

| Constant | 0.25 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.045 |

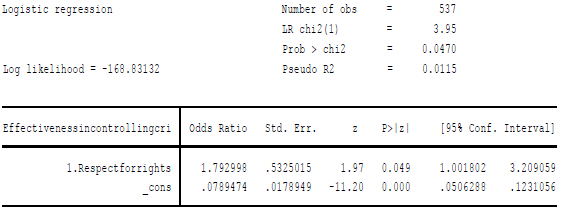

Another reasonable way of measuring police legitimacy is through citizens' evaluations of police effectiveness in controlling crime. In this way, those who believed that their rights were respected reported larger odds-1.793 times larger-of having evaluated police effectiveness in controlling crime as good than respondents who disagreed that their rights were respected (p<0.05) (Table 4). It is noteworthy that there might have been confounding variables. For example, differences explained by patrol methods. Reiner reviews an experiment done in New Jersey where foot patrols had an impact on citizens evaluating more positively police services and feeling less worried about crime111.

TABLE 4 LOGISTIC REGRESSION FOR ASSESSMENT OF POLICE EFFECTIVENESS IN CONTROLLING CRIME AS GOOD

| Odds ratio | Standard error | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for rights | 1.793 | 0.532 | 0.049 |

| Constant | 0.079 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.011 |

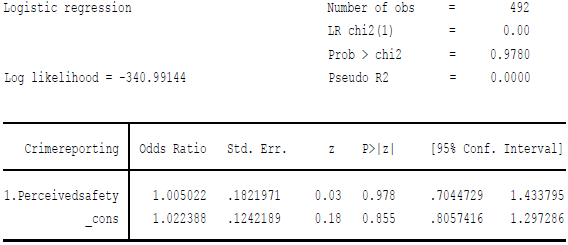

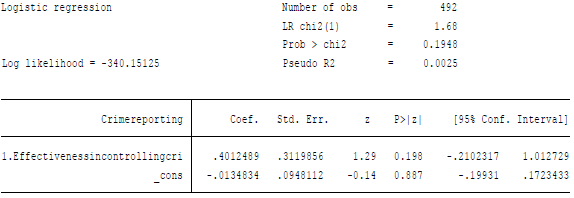

Finally, I tested the association between strength of social order (perceived safety of the neighbourhood and perceived police effectiveness) and police legitimacy (crime reporting). Yet, the data gathered did not offer evidence of any statistically significant association between these two variables. It is worth drawing the attention to the wording of the question that asked on perceived safety in the neighbourhood: "Using a scale from 1 to 6, where 1 means very unsafe and 6 means very safe, how safe do you feel in your neighbourhood?" Perhaps this leading question could have had an effect on the results.

Bradford et al. hold that the fact that police effectiveness is a more important predictor of police legitimacy than procedural justice in the South African context might be a consequence of the existence of alternative security providers, such as private security and vigilante groups112. If these authors are right, it is surprising that I did not find an association between police effectiveness and legitimacy. In Colombia, there are paramilitary and guerrilla groups that provide security in some regions113. Coupled with this, private security is a growing industry. Acero maintains that in Colombia there are more private security agents than police officers. In 2017, there were 244,757 private security agents versus 180,000 police officers114. Hence, further research should focus on the complex interplay between private security, vigilante groups and trust in the police.

This lack of association in Bogota, Medellin and Cali differs from the work of García-Sánchez et al. who showed a positive correlation between safety in the neighbourhoods and police legitimacy using pooled data from the American countries115, Tyler et al. who confirmed a positive correlation between perceived order in the neighbourhoods and police legitimacy in the United States116, and Tankebe117 and Bradford et al.118, who found a positive correlation between police effectiveness, cooperation and police legitimacy in Ghana and South Africa, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite all the limitations and its lack of representativeness, this is the first article that provides empirical evidence of an association between procedural justice and police legitimacy in Colombia, particularly in Bogota, Medellin and Cali. According to its findings, respect for rights during involuntary contacts with the police had a positive correlation with better assessments of police service during public-initiated contacts and better public evaluations of police effectiveness in controlling crime. Giving that these findings did not prove a causal link and they lacked generalisability, replications are encouraged to confirm or deny the results achieved. These results suggest, however, that procedural justice has to be taken into account by the police as it could enhance the perception that citizens have of them and, eventually, produce more law-abiding and cooperative citizens, as the literature has shown119.

The data analysed did not reveal associations between police legitimacy, on the one hand, and perceived police effectiveness and perceived safety of the neighbourhood, on the other hand. Nevertheless, this cannot be interpreted as lack of association between strength of social order and police legitimacy given that strength of social order is a broad concept that comprises many variables, which should be tested in further research.

Finally, the fact that some of my findings differ from the hypotheses raised cannot be regarded as a failure. These findings, on the contrary, are an invitation to further and more sophisticated research into a relevant topic which has been neglected in Colombia. Similarly, these results confirm that social science research is heavily dependent on contexts. Thus, variables that in some countries and social contexts could be strongly associated in others they might not, as seen here.