Introduction

By intentionally managing shade trees alongside crops, agrosystems possess the capacity to create habitats and preserve wildlife species within extensively modified tropical landscapes 1. Coffee and cocoa agrosystems are widely recognized as the most familiar examples, frequently characterized by a diverse array of shade tree species forming a prominent and dense canopy 2. Hence, the significance of these shade trees is profound, and they exhibit considerable variation in their characteristics. They can be categorized into three main types: 1) Polycultural system: In this approach, multiple species of shade trees, including forest species, are intentionally planted alongside the crop trees. The shade trees are interspersed throughout the plantation, creating a diverse and mixed canopy that benefits the cocoa or coffee plants, 2) Monocultural shade: This type of system is characterized by a dominant shade tree species or a few selected species that primarily provide shade for the crops. The shadow cast by these trees dominates the agrosystem, 3) Diversity shade systems: These systems encompass a wide range of shade tree species, typically consisting of around 30 to 40 different plant species. This diversity includes both fruit-bearing and timber species. The spine of these systems typically consists of fast-growing nitrogen-fixing legumes such as Erythrina spp., Gliricidia sepium, Samanea saman, and Inga spp. In all of these approaches, the shade trees play a crucial role in providing the necessary shade and microclimate for the cocoa or coffee plants to thrive, while also contributing to the overall ecological diversity and sustainability of the agrosystem 3.

Shade trees utilized in cocoa agrosystems globally share commonalities with those found in plantations in Mexico. In Ghana, for instance, shade tree species such as Persea americana, Citrus senensis, Gliricidia sepium, Ceiba pentandra, Cedrela odorata, and Spondias mombin are commonly employed in cocoa agrosystems (Abdulai et al., 2018). In Brazil, cocoa agrosystems make use of shade tree species like Spondias mombin, Cedrela odorata, Guazuma ulmifolia, Ceiba pentandra, and Genipa americana. These trees contribute to the shade and overall ecological dynamics of cocoa plantations in the country 4. In Colombia, cocoa agrosystems incorporate shade tree species such as Spondias mombin, Psidium guajava, Swietenia macrophylla, Cordia alliodora, Annona muricata, Guazuma ulmifolia, Artocarpus altilis, Pouteria caimito, Gliricidia sepium, Persea americana, Musa paradisiaca, Cedrela odorata, and Ceiba pentandra. These diverse trees contribute to the shade and ecological composition of cocoa plantations throughout the country 5. Cedrela odorata, Spondias mombin, and Guazuma ulmifolia are among the shade tree species utilized in cocoa agrosystems in Bolivia. These trees play a crucial role in providing shade and contributing to the ecological balance within cocoa plantations in the country 6. In Cameroon, cocoa agrosystems incorporate shade tree species such as Ceiba pentandra, Citrus reticulata, Citrus sinensis, Persea americana, Psidium guajava, Spondias mombin, Mangifera indica, and Musa paradisiaca. These trees are deliberately planted in cocoa plantations to provide shade and contribute to the overall ecological balance within the agrosystems 7. In Costa Rica, shade tree species commonly found in cocoa agrosystems include Carica papaya, Castilla elastica, Cedrela odorata, Cocos nucifera, Genipa americana, Gliricida sepium, Leucaena leucocephala, Spondias mombin, and Samanea saman. These trees are intentionally cultivated alongside cocoa crops to provide shade and contribute to the ecological dynamics of the agrosystems in the región 8. In Nigeria, shade tree species such as Citrus sinensis, Mangifera indica, Psidium guajava, Citrus reticulata, Persea americana, Cocos nucifera, Ceiba pentandra, and Spondias mombin are commonly found in cocoa agrosystems. These trees are deliberately grown alongside cocoa crops to provide shade and contribute to the overall ecological balance within the agrosystems in the country 9. In Indonesia, cocoa agrosystems incorporate shade tree species including Mangifera indica and Swietenia macrophylla. These trees are intentionally planted alongside cocoa crops to provide shade and contribute to the ecological dynamics of the agrosystems in the country 10. In Ecuador, Cedrela odorata is a shade tree species commonly used in cocoa agrosystems. It is intentionally cultivated alongside cocoa crops to provide shade and contribute to the ecological balance within the agrosystems in the country 11. In Peru, cocoa agrosystems incorporate shade tree species such as Cedrela odorata, Persea americana, and Swietenia macrophylla. These trees are deliberately planted alongside cocoa crops to provide shade and contribute to the overall ecological balance within the agrosystems in the country 12.

The presence of diverse shade trees in cocoa plantations (Theobroma cacao) offers valuable habitats for the conservation of wildlife. These trees serve as crucial spaces that support a wide range of organisms, including insects, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals 13. Cocoa is a prominent crop that is often associated with a wide array of shade trees, showcasing substantial diversity 14. Spondias mombin, Cedrela odorata, Persea americana, Mangifera indica, and Citrus sinensis are among the frequently employed shade tree species in cocoa plantations worldwide 15. Guazuma ulmifolia, Ceiba pentandra, Erythrina americana, and Samanea saman are the prevalent shade tree species found in cocoa plantations in Tabasco. These trees are commonly utilized to provide shade for cocoa trees in the region 16;17. The objective of this research is to calculate the similarity indices of shade trees used in cocoa agrosystems in the region of Comalcalco, Tabasco, Mexico.

Methodology

Characterization of the study área

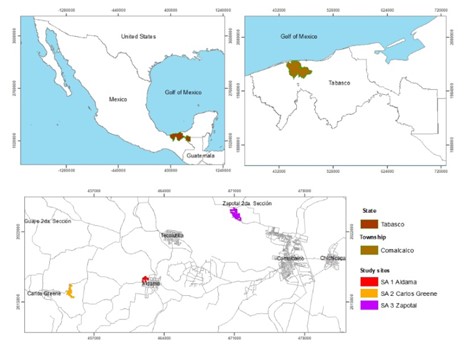

The research was conducted in three distinct cocoa agrosystems situated in the Comalcalco region of Tabasco, Mexico (Figure 1). For this study, three specific cocoa agrosystems were chosen as the designated research sites.

Sampling procedure

To assess the vegetation structure within the cocoa agrosystems, the three study sites (listed in Table 1) were utilized. In each of these sites, a total of 10 plots measuring 25 × 10 meters were selected, resulting in a plot area of 250 square meters. This approach followed the recommendations proposed by 18. In total, 30 Temporary Sample Plots (TSPs) were established, and measurements including diameter at breast height (DBH), total height, and crown diameter were recorded for all individuals with a DBH of 1.3 meters or greater.

Characterization of the dynamic of shade trees in cocoa agrosystems

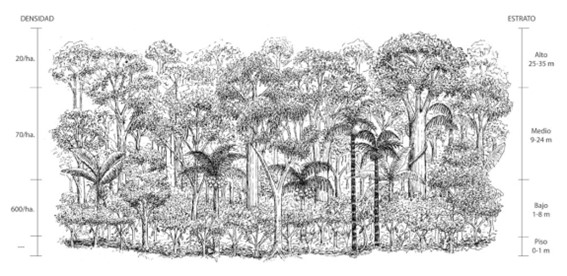

The cocoa agrosystems are characterized by their integrated polycultivation approach, where different plant types are strategically arranged in layers and tiers, spanning from the sun-exposed areas to the shaded regions (as depicted in Figure 2). This multi-layered system promotes biodiversity and provides varying levels of light and shade for the different plants grown within the agrosystems.

Dasometric variables

The trees within the cocoa agrosystems were taxonomically identified and marked with GPS coordinates for georeferencing purposes. Various dasometric variables were recorded, including the diameter at breast height (DBH) at 1.3 meters above the ground, crown diameter measured using a tape, and total height (Ht) measured using a clinometer, following the methodology outlined by 20.

Diameter at breast height (DBH)

After establishing the plots, a direct measurement of the diameter at breast height (DBH) was conducted for all trees within each Temporary Sample Plot (TSP). Only one reading of DBH was taken for each tree present in the TSPs, where 𝐷𝐵𝐻=𝐶/π𝐷𝐵𝐻=𝐶/π.

Determination of canopy height

To overcome the challenges associated with directly measuring canopy heights, an indirect approach was employed. A clinometer was utilized to measure the angles of the tree base (θ), the canopy (ρ), and the horizontal distance (hd). This method allowed for an estimation of canopy heights in situations where direct measurements were impractical, using the following basic trigonometric formula: Ht=hd (tan𝜌+tan𝛳) Ht=hd (tan(tan𝜌+tan𝛳).

Determination of crown diameter (CD)

To determine the crown diameter within each Temporary Sample Plot (TSP), the projection of the crowns was measured in two directions: primarily North-South and East-West. This approach allowed for the assessment of crown dimensions within the TSPs in multiple orientations, taking as reference the projection of the ends of the same on the ground CD= (cd1+cd)2/ 2CD=(cd1+cd)/2 11.

Using the collected measurement data, a database was created to facilitate the calculation of Basal Area (BA), which represents the cross-sectional area of a tree measured at a height of 1.30 meters. The Basal Area was computed using the following formula: BA= 0.7854* DBH2BA=0.7854*DBH2 where BA = Basal area in m² and DBH = diameter at breast height in m².

Sorensen Similarity Index

In order to assess the floristic similarity among the three study sites included in this investigation, the Sorensen Similarity Index (ISS) was employed. This index allowed for a comparison of the shared plant species between the study sites, providing insights into their floristic resemblance. ISS = [(2C) /(A+B) *100]

Morisite-Horn Index

The Morisita-Horn model is widely utilized as a means to quantify similarity between ecological communities. This model possesses certain attributes that render it valuable, such as its ability to minimize the influence of species richness and sample size. However, it is worth noting that the model is greatly influenced by the abundance of the most common species within the communities being compared. Where, IM-H = 2 Σ (ani bni) / [(da + db) (aN) (bN)]. Where, aN = number of individuals of community A, and ani = number of individuals of the ith species in A. is = Σ an² /aN².

Statistical analysis

The mean values of vegetation height, diameter at breast height, and crown diameter per plot were analyzed using the t-student test for independent samples. This statistical test was employed to compare the means and determine the presence of significant differences in the dasometric variables among the study sites. By applying this test, we obtained an indicator of the observed significant differences in the dasometric variables between the different study sites.

Results

Average height and diameter

The shade trees associated with cocoa in SA 1 and SA 2 exhibit larger dimensions, with an average height of 16.40 m and 15.47 m, and a crown diameter of 7.55 m and 7.38 m, respectively, as indicated in Table 2. In contrast, the trees in SA 3 are comparatively smaller in terms of height and diameter.

Basal area

The average basal area of cocoa trees within the 3 to 7-meter stratum is recorded as 21.7 m2, as presented in Table 3. In comparison, the associated plants in the other strata of SA 1 and SA 2 exhibit larger average basal areas of 156 m2 and 208 m2, respectively, within the agrosystems. Notably, the basal area of cocoa trees and shade trees in SA 3 is significantly smaller when compared to the other study sites.

Table 3 Total basal area of cocoa agrosystems

| Height stratum | SA 1 | SA 2 | SA 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Area (m2) | Trees m2 ha-1 | Basal Area (m2) | Trees m2 ha-1 | Basal Area (m2) | Trees m2 ha-1 | |

| 3-7 m | 21.88 | 3321 | 23.15 | 7494 | 20.25 | 1254 |

| 8-11 m | 38.71 | 565 | 28.44 | 2718 | 28.44 | 678 |

| 12-15 m | 79 | 159 | 79 | 656 | 63.99 | 267 |

| 16-19 m | 240 | 24 | 255 | 126 | 79 | 141 |

| >20 m | 270 | 12 | 470 | 49 | 177.75 | 11 |

Field sampling

A total of 16 families were identified within the three cocoa agrosystems selected as study sites, as indicated in Table 4. Among these families, Fabaceae displayed the highest number of species, with a total of six species. Sapotaceae was represented by three species, while Malvaceae, Anacardiaceae, Bignoniaceae, Lauraceae, Meliaceae, Moraceae, and Rutaceae each had two species within the agrosystems.

Table 4 Tree species are found in three cocoa agrosystems in Comalcalco, Tabasco

| Family | Scientific name | Common name | Height (m) | Agrosystems | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA 1 | SA 2 | SA 3 | ||||

| Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica | Mango | 10-30 | X | ||

| Spondias mombin | Jobo | 10-30 | X | X | X | |

| Spondias purpurea | Ciruela | 3-8 | X | |||

| Annonaceae | Annona muricata | Guanábana | 3-8 | X | ||

| Annona reticulata | Annona | 6-8 | X | |||

| Bignoniaceae | Tabebuia rosea | Maculis | 10-30 | X | X | X |

| Burseraceae | Bursera simaruba | Palo mulato | 20-35 | X | ||

| Fabaceae | Erythrina americana | Mote | 10-30 | X | X | |

| Inga jinicuil | Jinicuil | 12-15 | X | X | ||

| Gliricidia sepium | Cocoite | 12-20 | X | |||

| Tamarindus indica | Tamarindo | 10-30 | X | X | ||

| Samanea saman | Samán | 25-50 | X | X | ||

| Leucaena leucocephala | Guaje | 3-6 | X | |||

| Lauraceae | Cinnamomum zeylanicum | Canela | 10-15 | X | ||

| Persea schiedeana | Chinin | 8-25 | X | |||

| Persea americana | Aguacate | 10-20 | X | X | ||

| Malpighiaceae | Byrsonima crassifolia | Nance | 3-7 | X | ||

| Malvaceae | Ceiba pentandra | Ceiba | 20-70 | X | X | |

| Guazuma ulmifolia | Guácimo | 8-15 | X | |||

| Meliaceae | Cedrela odorata | Cedro | 10-35 | X | X | X |

| Swietenia macrophylla | Caoba | 35-50 | X | |||

| Moraceae | Artocarpus altilis | Castaña | 12-21 | X | ||

| Castilla elástica | Hule | 20-25 | X | |||

| Myrtaceae | Pimenta dioica | Pimienta | 6-8 | X | ||

| Psidium guajava | Guajava | 3-10 | X | |||

| Syzygium jambos | Pomarrosa | 10-16 | X | |||

| Rutaceae | Citrus latifolia | Limón | 3-6 | X | ||

| Citrus sinensis | Naranja | 9-10 | X | |||

| Citrus nobilis | Mandarina | 2-6 | X | |||

| Citrus aurantium | Naranja agria | 3-5 | X | |||

| Sapindaceae | Talisia olivaeformis | Guaya | 15-20 | X | ||

| Nephelium lappaceum | Rambutan | 12-20 | X | |||

| Sapotaceae | Chrysophyllum cainito | Caimito | 10-25 | X | ||

| Manilkara sapota | Chicozapote | 25-30 | X | |||

| Pouteria sapota | Zapote | 15-45 | X | X | ||

| Oxalidaceae | Averrhoa carambola | Carambola | 3-5 | X | ||

| Bixaceae | Bixa orellana | Achiote | 2-5 | X | ||

| Boraginaceae | Cordia alliodora | Laurel | 7-25 | X | ||

| Caricaceae | Carica papaya | Papaya | 2-8 | X | ||

| Musaceae | Musa paradisiaca | Platano | 1-3 | X | ||

| Muntingiaceae | Muntingia calabura | Capulin | 3-8 | X | ||

| Rubiaceae | genipa americana | Jagua | 15-25 | X | ||

Similarity indices

In terms of the similarity between the study sites (as shown in Table 5), Sorensen’s qualitative index indicates that SA 1 and SA 2 exhibit the highest similarity in terms of species composition. On the other hand, the Morisita-Horn index suggests that the three study sites have a similar overall structure, considering both species composition and their relative abundance. SA 1 and SA 2 demonstrate a similarity of 27.46%, followed by SA 2 and SA 3 with 27.27%, while SA 1 and SA 3 exhibit a slightly lower similarity in structure at 26.52%.

Statistical analysis of dasometric variables

Among the dasometric variables examined, the diameter of the tree crown was the only one that exhibited statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) when comparing the means between the study sites, as presented in Table 6.

Table 6 Significant differences in the averages of the diameter of the Crown

| t Grouping | Mean | N | TREAT |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 6.1742 | 10 | SA 2 |

| A | 5.9353 | 10 | SA 1 |

| B | 4.5151 | 10 | SA 3 |

Based on the calculated values for the sites Aldama-Zapotal, Zapotal-Greene, and Aldama-Greene, the obtained values of TT = ± 2.2622 and FT = 3.18, with α = 0.05, indicate the presence of statistically significant differences, as indicated in Table 7.

Table 7 Average comparison values for the variables height, diameter at breast height, crown diameter and basal area.

| Variables | SA 1 - SA 3 | SA 2 - SA 3 | SA 1 - SA 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t Value | Value F | t Value | Value r F | t Value | Value F | |

| DHB | 2.11 | 4.52 | -1.11 | 4.76 | 0.02 | 7.24 |

| CROWN | 4.66 | 2.09 | -5.11 | 2.19 | -0.33 | 4.58 |

| HEIGHT | 1.58 | 4.40 | -0.14 | 4.36 | 1.29 | 4.91 |

| BA | 2.54 | 3.22 | -1.03 | 53.73 | -0.32 | 16.67 |

Discussion

As a result of habitat fragmentation and loss, certain species including insects, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals have sought refuge in cocoa and coffee agrosystems 21. It is important to acknowledge that these available habitats cannot be compared to pristine rainforests, which offer ideal conditions for many species due to their biotic and abiotic processes. However, for some endangered species, agrosystems represent their only available habitat. These agrosystems possess the potential to provide suitable habitats for wildlife conservation due to their tree diversity and canopy structure across different strata 1. The presence of various strata within cocoa plantations offers numerous benefits and ecosystem services, including water collection and purification, soil conservation, crop pollination, carbon sequestration, decomposition of organic waste, species conservation, protection against ultraviolet rays, partial climate stabilization, and the aesthetic appeal of natural environments 22. Consequently, it is important to consider providing economic incentives or implementing payment programs for environmental services to small-scale producers. This approach would encourage them to conserve and enhance tree cover in their cocoa plantations 23.

The presence and behavior of shade trees in cocoa agrosystems play a significant role in plant-animal interactions, population dynamics, and the evolutionary processes of animals that rely on plants for sustenance 24;25. Both abiotic and biotic factors influence the structural characteristics of agrosystems, such as canopy height and species distribution, which are crucial for maintaining diverse strata and the abundance of trees 26. The dynamic of shade trees in cocoa agrosystems holds great importance due to their composition, structure, and diversity, as they create favorable conditions to support the conservation of wildlife species 14. The dynamic of shade trees in cocoa agrosystems is commonly classified into five levels, including the emerging layer, canopy, undergrowth, and soil layer 27;28. Additionally, the dynamic of shade trees in cocoa agrosystems is classified as high, medium, low, and floor, indicating different levels of presence and distribution 29.

Certain tree species found in these study sites serve as fruit trees, including Citrus sinensis, Mangifera indica, Annona muricata, and Persea americana. Other trees present are valued for their use in forestry, such as Tabebuia rosae and Tabebuia guayacan. Notably, species like Cedrela odorata and Swietenia macrophylla, categorized as vulnerable according to the IUCN, are also found in these areas. Promoting the presence of shade trees in cocoa agrosystems is crucial for the conservation of wildlife species, as they create biological corridors that facilitate the movement and shelter of birds, insects, and mammals 30. Diversification in agrosystems has become an important strategy for producers to mitigate economic losses resulting from price fluctuations and low coffee and cocoa production 31. These strategies primarily involve diversifying the range of crops, including staple crops, vegetables, fruits, timber, ornamental plants, and even animals 32.

By incorporating shade trees and enhancing biodiversity within the system, diversification can improve the provision of ecosystem services without compromising coffee production 33.

In this study, the average height of trees was recorded as 11.67 m, with an average basal area of 38.71 m2 and a tree density of 49 m2 ha-1. These characteristics are similar to those observed in Mexico, where the average height is 11.28 m, the basal area is 34.1 m2, and the tree density is 45.75 m2 ha-1 34. In Cameroon, on the other hand, the mean height is 55.5 m, the basal area is 48.7 m2, and the density is 51.3 m2 ha-1 30. In Indonesia, the mean height is reported as 11.56 m, the basal area as 56.87 m2, and the density as 77.5 m2 ha-1 10. Ghana shows a mean height of 15.1 m, a basal area of 42.8 m2, and a density of 49 m2 ha-1 35. In Ecuador, the mean height is reported as 12.1 m, the basal area as 37.7 m2, and the density as 54.6 m2 ha-1 11. Lastly, in Costa Rica, the mean height is 21.1 m, the basal area is 25.5 m2, and the density is 61 m2 ha-1 36.

The presence of arboreal fauna at different levels of stratification is closely associated with the structural diversity of trees, making them vital components for biodiversity richness. In our study site, cocoa agrosystems serve as the primary habitat for wildlife, representing the closest resemblance to a natural forest due to the dynamic of shade trees within the cocoa agrosystems. Within these agrosystems, various habitats can be identified: 1) house gardens and cover crops: These areas support a wide range of fauna, including insects, spiders, and some mammals such as anteaters, wild boars, tapirs, and jaguars. The substantial amount of litter that falls to the ground in these areas is rapidly decomposed by termites, worms, and fungi, 2) ornamental shade and fruit trees: These trees provide habitats for snakes and certain bird species. They contribute to the diversity of fauna found within the agrosystems, 3) managed foliage and nitrogen-fixing legumes: These areas attract a variety of birds, including toucans, as well as mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. The presence of foliage and legumes creates suitable conditions for their survival, 4) emergent production palms and trees: These tall trees are particularly important for bird species like the scarlet macaw and other unique species. They serve as essential habitats within the agrosystems. The dynamic of shade trees in cocoa agrosystems plays a crucial role in providing these diverse habitats for wildlife, compensating for the loss of natural forest habitats.

Conclusion

Field measurements were conducted to determine the dasometric variables of shade trees within cocoa agrosystems. These variables included canopy height, crown diameter, and diameter at breast height. The information obtained from these measurements is crucial for calculating the index of importance and forest value of the shade trees. These attributes are significant as they can serve as input variables or parameters for predicting available habitats using ecological niche models and assessing habitat quality, particularly for birds and arboreal primates. Cocoa plantations, thanks to the presence of shade trees, have the potential to serve as important refuge areas for various species, including insects, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. This is especially evident when comparing them to more intensive agricultural practices that lack such diverse habitats. To enhance the assessment of shade tree dynamics in cocoa agrosystems, the use of LiDAR technology is recommended. This tool allows for the measurement of parameters related to shade tree dynamics and enables the quantification of species-habitat relationships. Such information is valuable for supporting conservation efforts and promoting the persistence of local populations.