INTRODUCTION

The physician-patient relationship (PPM) is “a professional- interpersonal relationship that serves as the basis for health management. It is a relationship where a service of great importance is provided since health is one of the most precious aspirations of the human being” 1. The PPM is based on freedom of choice and identifying and sharing their respective autonomies and responsibilities. The physician in the relationship seeks a care alliance based on mutual trust and respect for values and rights and supplying comprehensive and complete information, considering communication time as healing time 2. For the American Medical Association code, it is a moral activity that arises from the imperative of caring for patients and alleviating suffering, becoming a matter of clinical ethics guided by trust, freedom, and ethical responsibility 3.

Beauchamp and Childress have identified four principles that distinguish health care: autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. The emergence of the principle of autonomy profoundly impacted the PPR 4 but not always positively.

Historically, PPR has been idealized and framed in terms of benevolent determinism characterized by patient trust and physician availability in a long-term relationship; however, social and cultural changes have affected this relationship 5,6. The patient has become more active and participatory; now, the patient recognizes the right and freedom to decide on their care 7,8.

In the Anglo-Saxon principlism literature, a transition from disease-centered medicine to patient-centered medicine is promoted since it assumes the empowerment of patients to take an active role in their care and the construction and organization of care systems 9-11. Chochinov proposed dignity as a fundamental value of the care model in medicine 12,13.

A few years ago, the term Bioethics was alien to the context of the practice of medicine and is currently inherent to it; its objective is to distinguish between “what should be” and what “should not be” in actions that affect human and nonhuman life 14. When it comes to medical action, it is called “medical ethics.” The medical actions based on the four principles mentioned were enriched in the 1990s with the principles of dignity, integrity, and vulnerability 15 (Table 1).

Table 1 Ethical principles, values , and conditions investigated in the questionnaire

| Principle | Definition |

|---|---|

| Autonomy | People choose an action rationally, based on a personal appreciation of future possibilities and their value system 16,17 |

| Dignity | All human beings are equal since everyone deserves respect and esteem regardless of individual differences 16,17 |

| Beneficence | It refers to the obligation to prevent or alleviate harm, to do good, from the trust between the physician and the patient as a process characterized by empathy and communication 17 |

| Justice | Equality in the dignity and rights of human beings must be translated into unique and personalized attention where everyone is treated according to their needs and without discrimination 17,18 |

| Vulnerability | It is a condition of the fragility of the human being in terms of their biological, psychological, or social condition, which must be protected, especially when it comes to severe and catastrophic disease in patients 19. |

Source: Own elaboration.

With the Barcelona Declaration, the need to value the notion of vulnerability becomes relevant. It is placed together with the notions of autonomy, integrity, and dignity, allowing a different approach to medicine from a framework of solidarity and social responsibility. The consideration of vulnerability as a notion of the precariousness of all living beings, human and non-human, who are exposed throughout their existence to the risk of being injured, ennobles the bioethical discourse that traditionally focused on autonomy and justice, putting aside traditionally paternalistic care stands 20,21.

Eight years ago, we began to train residents and physicians of the Nephrology Service of the Hospital General de México in ethics and anthropology to promote humanism in their medical work. We decided to build and validate an instrument to identify the bioethical principles in the PPR. Once validated, we intend to know the results of the scales administered to the patients of the Nephrology Service.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

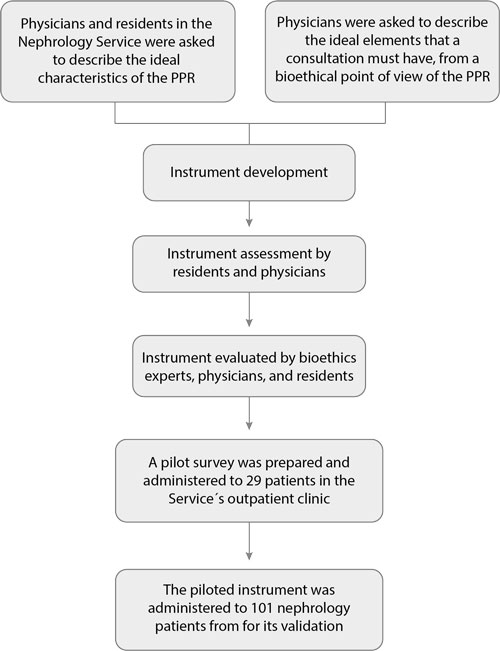

We sought to build an instrument to evaluate the presence of enriched bioethical principles in the care of patients of this service and hospital, which was validated after being piloted and reviewed by health personnel involved and experts in bioethics (Figure 1).

A questionnaire called ReMePaB (acronym in Spanish for PPR with bioethical principles) with twenty-one questions was obtained. It included four questions about autonomy (5, 6, 10, and 19), two dichotomous questions referring to informed consent, three on beneficence (15, 18, and 20), five on dignity (1, 2, 3, 14, and 21), three on justice (4, 12, and 13), and four on vulnerability (7, 8, 9, and 11), all on a Likert scale.

Table 2 Reliability of the questionnaire for the bioethical principles, pilot test (n = 29)

| Test | Retest | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Mean | Standard deviation | Cronbach's alfa | Mean | Standard deviation | Cronbach's alfa |

| Autonomy | 6.34 | 3.19 | 0.94 | 6.45 | 3.21 | 0.94 |

| Beneficence | 4.31 | 1.29 | 0.96 | 4.17 | 1.51 | 0.95 |

| Dignity | 6.48 | 2.28 | 0.95 | 6.55 | 2.59 | 0.94 |

| Justice | 4.83 | 2.14 | 0.95 | 5.10 | 2.38 | 0.95 |

| Nonvulnerability | 7.24 | 3.80 | 0.95 | 7.79 | 3.76 | 0.95 |

Source: Own elaboration.

The test-retest was carried out as part of the instrument validation in the Nephrology Service outpatient clinic. After explaining the study’s objectives and procedures to the participants, they signed the informed consent and were interviewed face to face during the test; it was explained to them that 24 hours later, they would receive a phone call for the retest.

Table 3 Reliability of each question of the ReMePaB questionnaire. Presentation of the mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach's Alpha (n = 29)

| Question | Mean | Standard deviation | Cronbach's alfa |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Did the doctor who treated you introduce himself? | 1.18 | 0.39 | 0.97 |

| 2. Did the doctor call you by name? | 1.11 | 0.31 | 0.97 |

| 3. Do you think the doctor greeted you cordially? | 1.54 | 0.88 | 0.97 |

| 4. Do you think the doctor received you on time? | 2.04 | 1.10 | 0.97 |

| 5. Did the doctor allow you to talk about your health condition? | 1.50 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| 6. Did the doctor devote the necessary time to your consultation? | 1.54 | 0.88 | 0.97 |

| 7. Did the doctor explain your health condition? | 1.54 | 1.07 | 0.97 |

| 8. Did the doctor explain the lab results? | 1.89 | 1.23 | 0.97 |

| 9. Did the doctor explain the medical treatment to follow? | 1.57 | 1.07 | 0.97 |

| 10. Did the doctor explain the care you should have? | 1.79 | 1.17 | 0.97 |

| 11. Did the doctor explain the procedures (dialysis, hemodialysis, x-rays, endoscopy, etc.) you should undergo? | 2.29 | 1.36 | 0.97 |

| 12. Was the doctor's information clear to you? | 1.32 | 0.67 | 0.97 |

| 13. Did the doctor allow you to express your doubts? | 1.46 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| 14. Do you think the doctor treated you warmly? | 1.29 | 0.66 | 0.97 |

| 15. Did someone take your vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, etc.)? | 1.04 | 0.19 | 0.97 |

| 18. Was the physical examination performed by the doctor sufficient? | 1.96 | 1.14 | 0.97 |

| 19. Were your doubts clarified? | 1.46 | 0.84 | 0.97 |

| 20. Did the doctor and you agree about the main health problem for which you came today? | 1.25 | 0.59 | 0.97 |

| 21. Do you think the doctor treated you as a person? | 1.32 | 0.72 | 0.97 |

Source: Own elaboration

After the pilot test with the instrument ReMePaB, it was administered again to patients in the outpatient clinic of the nephrology service from March 1 to April 30, 2018, at the same institution for validation. All the questionnaires were in Spanish since it is the participants’ mother tongue.

An interviewer applied the scale in person. The inclusion of the patients was consecutive as they left the consultation and agreed to participate. The questionnaire also included demographic variables such as age, sex, years of studies, diagnosis, time of coming to the consultation, residence, occupation, socioeconomic level, and the application of the Zung questionnaire to determine the presence or absence of depression in the participants.

The Zung Depression Scale is a self-report that measures depressive symptoms. It is made up of twenty statements related to depression, and of these, ten are proposed in affirmative terms and ten in negative terms. Somatic and cognitive symptoms take a great weight, each consisting of eight items, two more that refer to mood, and another two that refer to psychomotor symptoms. The response options follow a 1-4 Likert-type scale where 1 is very seldom; 2, sometimes; 3, many times, and 4, almost always.

Concerning the answers to the scale to determine each bioethical principle, “yes” was considered in the case of dichotomous questions; in the rest of the reagents, the answers ranged from “nothing” to “a lot” (Table 4).

Table 4 Description of the mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s Alpha of the ReMePaB questionnaire (21 questions) (n = 101)

| Question | Mean | Standard deviation | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1 | 1.12 | 0.33 | 0.80 |

| Question 2 | 1.04 | 0.20 | 0.81 |

| Question 3 | 1.25 | 0.59 | 0.80 |

| Question 4 | 1.69 | 1.00 | 0.80 |

| Question 5 | 1.14 | 0.49 | 0.80 |

| Question 6 | 1.16 | 0.52 | 0.80 |

| Question 7 | 1.15 | 0.57 | 0.80 |

| Question 8 | 1.31 | 0.70 | 0.80 |

| Question 9 | 1.22 | 0.64 | 0.80 |

| Question 10 | 1.40 | 0.87 | 0.79 |

| Question 11 | 1.69 | 1.02 | 0.81 |

| Question 12 | 1.11 | 0.40 | 0.80 |

| Question 13 | 1.13 | 0.44 | 0.80 |

| Question 14 | 1.25 | 0.61 | 0.80 |

| Question 15 | 1.05 | 0.22 | 0.81 |

| Question 18 | 1.87 | 1.04 | 0.80 |

| Question 19 | 1.25 | 0.65 | 0.79 |

| Question 20 | 1.17 | 0.55 | 0.80 |

| Question 21 | 1.17 | 0.38 | 0.80 |

Source: Own elaboration

It was an observational and descriptive study. This study was approved by the institution’s Research and Research Ethics Committees and registered under number DI/18/105B/006.

The data obtained were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 21. The frequencies and percentages of the sample were calculated. Internal consistency was examined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient between items and components of the instrument, and the intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated to figure out the reliability and global consistency. A result equal to or greater than 0.6 was considered acceptable, obtaining a p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

For the pilot, the instrument was administered to 29 patients, obtaining the following values represented in Tables 2 and 3 for Cronbach’s Alpha and the means for each bioethical principle.

For instrument validation, 101 patients were interviewed with the ReMePaB. Regarding sociodemographic variables, the participants were between 18 and 84 years old (M = 50, SD 17); 70 % were men, and the average years of study were eight (SD 4), so 71 % have primary education. Marital status was married or in a domestic partnership 57 %, single 34 %, and widowed or divorced 10 %. Of those interviewed, 48 % came from the State of Mexico, 41 % from Mexico City, and the rest from other states. As for occupation, 30 % were homemakers, 23 % were unemployed, 45 % worked in different trades, and 2 % were pensioners. Regarding the socioeconomic level, 88 % have low income. In the case of the type of consultation, 87 % were subsequent, and 64 % knew their diagnosis. In 82 cases, no depression was detected with the Zung scale.

The reliability analysis of the questionnaire was performed, and Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each question (Table 4), obtaining an intraclass correlation coefficient for the instrument of 0.81 (p < 0.05) with a 95 % confidence interval of 0.75-0.86 (Table 5).

Table 5 Description of the mean, variance, and Cronbach’s alpha for each bioethical principle analyzed ( n = 101)

| Bioethics principles (# of questions comprising it) | Scale mean | Scale variance | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy (4) | 19.21 | 19.85 | 0.63 |

| Beneficence (3) | 20.06 | 24.74 | 0.71 |

| Dignity (5) | 18.33 | 23.56 | 0.68 |

| Justice (3) | 20.22 | 24.29 | 0.70 |

| Nonvulnerability (4)* | 18.78 | 20.45 | 0.75 |

*The lower the score, the lower the perception of the vulnerability condition.

Source: Own elaboration

The bioethical principles studied, the related questionnaire items, and the number of participants who answered “yes” or “a lot” to each are presented in Table 6.

Table 6 Distribution of the questions by bioethical principle and number of participants who answered “yes” or “a lot” (n = 101)

| Questions | Frequencies (n) |

|---|---|

| AUTONOMY. Four items | |

| 5. Did the doctor allow you to talk about your health condition? | 92 |

| 6. Did the doctor devote the necessary time to your consultation? | 90 |

| 10. Did the doctor explain the care you should have? | 80 |

| 19. Were your doubts clarified? | 86 |

| BENEFICENCE. Three items | |

| 15. Did someone take your vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, etc.)? | 96 |

| 18. Was the physical examination performed by the doctor sufficient? | 55 |

| 20. Did the doctor and you agree about the main health problem for which you came today? | 90 |

| DIGNITY. Five items | |

| 1. Did the doctor who treated you introduce himself? | 89 |

| 2. Did the doctor call you by name? | 97 |

| 3. Do you think the doctor greeted you cordially? | 82 |

| 14. Do you think the doctor treated you warmly? | 83 |

| 21. Do you think the doctor treated you as a person? | 84 |

| JUSTICE. Three items | |

| 4. Do you think the doctor received you on time? | 62 |

| 12. Was the doctor’s information clear to you? | 93 |

| 13. Did the doctor allow you to express your doubts? | 91 |

| NONVULNERABILITY*. Four items | |

| 7. Did the doctor explain your health condition? | 93 |

| 8. How much did the doctor explain the lab results? | 81 |

| 9. Did the doctor explain the medical treatment to follow? | 89 |

| 11. Did the doctor explain the procedures (dialysis, hemodialysis, radiographs, etc.) you should undergo? | 64 |

*The lower the score, the lower the perception of the vulnerability condition.

Source: Own elaboration

The number of patients who answered “yes” or “a lot” to all the questions that made up each bioethical principle, and therefore, the bioethical principle present is described in Table 7.

Table 7 Number of participants who answered “yes” or “a lot” to all the questions that made up each principle (n = 101)

| Principle | Presence | Absence |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | 69 | 32 |

| Dignity | 67 | 34 |

| Justice | 60 | 41 |

| Beneficence | 53 | 48 |

| Nonvulnerability* | 54 | 47 |

*The lower the score, the lower the perception of the vulnerability condition.

Source: Own elaboration

It is observed that 69 % of the patients perceive autonomy to be present, followed by dignity and justice, while beneficence and vulnerability are manifested to a lesser extent.

In the case of the two questions about informed consent, we found that only 20 patients were asked to sign it, 16 of them were told what it consisted of, and the remaining four perceived deficiencies in the process. Informed consent did not play a relevant role in determining autonomy because medical practices requiring a signature are not carried out in the outpatient clinic; these questions apply more to hospitalized patients or those who undergo some intervention in studies or surgeries.

DISCUSSION

The construction of an instrument to evaluate the PPR was a meticulous process that allowed us to approach the bioethical principles that are most present in this relationship. There are instruments to measure the quality of medical care 22,23; others refer to the quality of medical care and its link with ethics, emphasizing that care must offer the best treatment, avoid harm, and have a sustainable and fair cost respecting the autonomy and rights of patients 19. Some did not evaluate the PPR and bioethical principles, which is crucial since it contemplates the human part of this relationship, the humanization of medicine 24.

In this case, from an approach to measuring bioethical principles, the number of questions for each was acceptable and, therefore, could be used as a reference. The results show that patients can take control of decisions according to the kidney disease that afflicts them, and the treatment and use of the resources available to the institution allow them to feel worthy.

Autonomy as a bioethical principle, where patients can take control of decisions about the kidney disease they suffer, dignified and fair treatment, and the use of the resources available to the institution, makes us think that bioethical principles are present in this study 19.

Regarding bioethical principles, in our research, autonomy was the principle with the highest score, reflecting that patients have a voice in the medical care they receive. It includes various concepts such as the right to know their health status, receive transparent, timely, and truthful information, ask for a second opinion, and accept or not a treatment, which is consistent with what Ocampo Martínez 25 points out. This author refers that the PPR has become a relationship between equals since both share autonomy as a value and as the practice of a right. Besides, Chin 26 points out that the patient can receive suggestions from his physician, but the former will be the one who decides to accept it or not and underlines this principle as a specific condition in health care 26.

Dignity, a principle inherent in every individual considered a human need and recognized as central in health sciences, showed in this study that, together with autonomy, they are present at Hospital General de México and help promote a practice of medicine that focuses attention on the person and not on the disease, favoring a more humanistic approach. Its preservation in medical care is crucial and involves aspects external to the patient (environment) and characteristics of the patient, such as their beliefs and values 27,28. To be treated as a person (as a unique individual), to be treated well, to be called by your name, to know the physician who treats you, to support your self-esteem, and to give you confidence, among other things, is to respect your dignity.

Justice refers to being treated based on patients’ rights in a non-discriminatory environment and following the needs of each person. Beneficence is understood as maximizing possible benefits, minimizing risks, and not harming 29. Although they are present in a sector of the investigated population, they remain improvement opportunities in the PPR.

Finally, vulnerability/non-vulnerability as a principle is also present in the investigated group, which is evident in both perspectives; that is, they do not seem to feel vulnerable when receiving medical care, which strengthens their autonomy (principle with the highest score). However, from the social vulnerability classification 30,31, it is a vulnerable population if we consider that the largest by percentage (88 %) have “low or meager” income, an average of eight years of studies, and a high rate of unemployment (45 %). It is significant to attend to this since the PPR does not only contemplate “the consultation time” but also the interpretation that the patient gives to the relationship that they establish with the person who is the depositary of their trust in an aspect as important as health.

CONCLUSIONS

An instrument has been developed to evaluate the PPR and the presence of extended bioethical principles, whose purpose is to enhance the dignity, beneficence, non-vulnerability, and autonomy of every patient who is cared for in the hospital and humanize medicine.

The expanded version of the principles of bioethics contemplated in the Barcelona Declaration 21 could promote the ethics of the first person, the ethics of virtue, where the ideal of human excellence is found, enabling the small virtues that facilitate work and human coexistence. In future research, the same instrument could be used with patients hospitalized and in other services. Another line of research could be the evaluation of human virtues in the PPR.

There is no doubt that details of courtesy, civility, politeness, punctuality, simplicity, diligence, optimism, good humor, joy, respect, and order make the disease and its signs and symptoms more bearable, in addition to promoting compliance with first-person ethics. With this vision, we would approach the ideal of virtue, a life worth living to overcome the vicissitudes of human existence.