Introduction

The aim of this paper is to analyze the complex relationship between bilingualism and the processes of expressing emotions and thoughts. In order to achieve this aim, the paper first provides a relevant theoretical framework on which the conducted research relies. The concept of bilingualism has been widely discussed in the literature, and what seems quite obvious is the fact that authors' interpretations of who counts as a bilingual are quite diverse. Analysis of the concept becomes more complex if its relevance in the process of identity construction is taken into consideration. Moreover, the relationship between bilingualism and ways of expressing emotions and thoughts is presented through specific criteria, such as the importance of age in L2 acquisition, environmental factors, dominance of a particular language in a particular period of life, etc. This is taken into consideration in the analysis of the results of the research carried out in March 2015.

The basic goal of this paper is to demonstrate whether research participants' second language is, and to what extent it is, the language preferred for expressing emotions and thoughts. A secondary aim is to validate some of the generalizations made by Pavlenko (2005; 2006; 2014), i.e. to test different factors influencing the choice of language used for different types of activities related to expressing emotions and thoughts. The hypothesis is that the first language (L1) is not always the first language chosen in processes under analysis but rather that sometimes the second language (L2) is selected first, or even a combination of both languages, in specific situations. The analysis of the data collected in the research is divided into two parts. The first is concerned with the relationship between bilingualism and the expression of emotions, as well as the different criteria which prove that a bilingual uses different languages in order to express emotions, while the second analyzes the relationship between bilingualism and cognitive processes. With regards to the formation of bilingual identity, it is presumed that different criteria have a role in the choice or the combination of languages, and that these are reflected in the relationship between the choice of languages in different types of linguistic expressions and the nature of the overall bilingual and bicultural identity.

Bilingualism and identity

The term bilingualism has been given different interpretations and connotations depending on the context within which it has been studied. From the sociolinguistic point of view, it is associated with contexts other than those strictly related to language and society as it is inextricably linked to the individual and the process of forming not only collective but individual identities, as well. Scholars are diverse in their attempts to address a variety of issues associated with the phenomenon of bilingualism. Among many others, the following are some of the general questions usually dealt with: Are bilinguals to be considered two personalities in one or two separate personalities? What processes are involved in switching from one language to another? What is the influence of the environment during language acquisition?

As was stated previously about the term bilingualism varying from author to author, some different proposals may be observed. A very broad definition is offered by Grosjean (2008) who proposes that "bilingualism is the regular use of two or more languages (or dialects), and bilinguals are those people who use two or more languages (or dialects) in their everyday lives" (p. 10). Besides such broad definitions, there are also those according to which reference should be made not only to the sociolinguistic perspective, but also the sociopsychological one. Liebkind (1995) proposes several conditions according to which a person may be considered bilingual. Besides the criteria of origin, language proficiency, and language function, a crucial condition refers to attitudes as well: "if you feel yourself to be bilingual and are identified as bilingual by others" (p. 80).

Most scholars agree that bilingualism is a difficult term to define. Besides the methodological problems related to both the researcher's level of objectivity and the precision in evaluating knowledge of languages, Adler (1977) raises other important issues related to the difficulty of defining who counts as a bilingual:

One could perhaps define bilingualism as the complete, or less complete, command of at least two languages, speaking, hearing, writing and reading them. It will be a matter of taste -or of severity- to include all of these activities into the definition. There are many cases of bilinguals who speak two languages fluently, but cannot write one or the other properly and grammatically, or neither. Can these people be called bilinguals? (p. 6)

Clearly, one of the major problems in defining bilingualism relates to differences of degrees of language competence in two receptive and two productive language skills. Baker (2011) implies that besides not taking into account the differences of degrees of language competence in L1 and L2 related to these four language skills, we may also fall into the trap of being "too exclusive" or "too inclusive" if we choose to analyze bilingualism from the point of view of the two extremes -identifying a bilingual as a person who has native-like competence in both languages, or as someone who has at least a basic competence in a second language (pp. 7-8).

In addition to the problems related to identifying a bilingual on an individual level, there is also the concept of societal bilingualism which needs to be taken into consideration. Having strong implications for research on language planning and language policy in different multilingual contexts, societal bilingualism is frequently analyzed together with individual bilingualism. This becomes evident in multilingual contexts where we can focus on "large numbers of individual bilinguals who function as linguistic mediators between the different groups present. It is these mediators who represent the link between societal and individual bilingualism" (Baetens Beardsmore, 1986, p. 5). Furthermore, societal and individual bilingualism are often analyzed in relation to different bilingual communities (see Hoffmann, 1996, p. 47). If we accept as a fact that there is no definite answer to the question of who exactly a bilingual is, we may also assume that the same problem arises in attempts to define who a monolingual is. Moreover, we may hypothesize that an absolute monolingual may not even exist. Using the term "unilingual" and based on the fact that both the processes of changing registers and languages include changes on all linguistic levels, Paradis (2007) proposes a similar claim and states that "unilinguals can mix registers the way bilinguals mix languages for a number of purposes, including jocularity" (p. 16). Therefore, it cannot be said with certainty that people who use only one form of a language exist. There are no pure monolinguals or unilinguals.

In relation to processes of forming different types of identities, being bilingual includes not only the use of two languages, but, in most cases, also management of two cultures in the sense that bilinguals might feel they are part of two different cultures to varying degrees. However, it is not always possible to identify an individual as bicultural even if they are bilingual. Bilingualism and biculturalism are two phenomena that, despite some overlaps, present specific differences in their manifestation within individuals. Correspondingly, Grosjean (2008) explains that "bilinguals can usually deactivate one language and only use the other in particular situations (at least to a very great extent), whereas biculturals cannot always deactivate certain traits of their other culture when in a monocultural environment" (p. 215). If we accept the definition that states that only basic competence in L2 is necessary for a person to be identified as a bilingual, then it is safe to assume that developing a bicultural identity is a very complicated process. Besides the linguistic factor, there are others that come into play. By becoming a part of both cultures, a person is no longer only bilingual, but also bicultural. In deciding on their own cultural identity, such individuals have to weigh factors such as the actual acquaintance with the two languages and cultures, family and personal experience, general perception and reception of the two cultures, etc. (Grosjean, 2008, p. 219).

Taking into consideration the topic of this paper, the focus of attention with regards to developing a bilingual's cultural identity must clearly be placed within affective dimensions. With regards to different motivations that come into play in the process of developing a bilingual and a bicultural identity, we may apply Clément's analysis of the affective dimensions that are relevant for L2 acquisition (1980) , according to which we may assume that there are two basic forces governing these affective dimensions -a desire for integration and a fear of assimilation. This means that the extent of the usage of L1, L2, or both in different contexts and for different purposes will also be governed by the relationship between these two forces within an individual. For example, Hamers and Blanc comment on the factors influencing the development of so-called additive balanced bilinguality (situations when both languages are developed and when L2 is reinforced while reinforcing L1, i.e. learning L2 is not carried out at the expense of L1), and claim that, in order for this type of bilinguality to occur, "the two languages and cultures must be favourably perceived and equally valorized" (1989, p. 128). It is quite clear that the overall identity of each bilingual speaker is unique and can hardly be compared to identities of monolingual speakers, primarily because it is much more complex and includes not only an array of linguistic but also affective and cognitive factors. This has relevance for the discussion of this paper since the nature and the extent of bilingualism and the linguistic choices that bilinguals make have a profound influence on their overall identity. Although this is not a part of the discussion of this paper, this influence is evident in the ways in which bilinguals who use both languages and switch between or mix them are perceived by others (especially monolingual speakers). On the other hand, with regards to the topic of our discussion, we may say that it is extremely difficult to put forward clear and unambiguous generalizations regarding the factors that come into play when a bilingual decides to use either L1, L2, or both languages in processes of expressing emotions or for performing cognitive operations since these are extremely personal and individual decisions. However, some of the informants' responses presented in subsequent parts of the paper clearly demonstrate the specific factors that govern their own choices regarding the use of L1, L2, or both languages in these processes.

Bilingualism and expressing emotions

Since the greater part of this paper deals with research on how bilinguals process and express their emotions and how this impacts the formation of their identity, it is necessary to look more closely at what is understood when the term 'emotion word' is used. Defining the term heavily relies on the level of abstractness and, from a semantic point of view, the relationship between word and referent. Unlike concrete words for which the association between referent and word is in most cases easily established via perceptual saliency, abstract words are more difficult to process because this association is more complex to establish. What category do emotion words fall into? From the semantic point of view, emotion words are those that carry an affective type of meaning. Furthermore, they can be distinguished along two axes -"level of arousal (i.e. low, moderate, or high)" and "valence (i.e. positive, negative, and neutral)" (Altarriba, 2006, p. 235). More importantly from the point of view of a bilingual speaker, it is necessary to identify the relevant factors that might be used to evaluate the mediation of language emotionality in such individuals. For the purposes of this study, we will rely on Pavlenko's (2005) "identification" (pp. 185-186). Factors are briefly presented here but explained in detail later on together with the results of the research. The first of these factors refers to the age of acquisition. Here, we can argue about the level of emotionality and whether the language first learned is more emotional. The second factor is the context of acquisition. If emotion words in second language are learned through intimate relationships, they will have high emotional value. On the other hand, emotion words learned in the second language in formal surroundings would have low emotional value. The third factor is the speaker's personal history of trauma, stress, and violence related to either L1 or L2. Additional relevant factors include language dominance, word type, and proficiency. The importance of these factors has been identified in different types of research, e.g. the importance of age and level of proficiency among English-Spanish bilinguals (see Harris, 2004; Harris et al., 2006).

Bilingualism and cognitive processes

Analyses of the possible relationships between different cognitive processes and bilingualism diverge greatly both in scope and methodology. There are many cognitive processes that may be investigated in terms of the usage of either L1 or L2. But what does it mean "to think in a language?" According to De Guerrero (2005), this notion basically refers to the concept of individuals' "verbal thought" and denotes "a purely introspective belief based on the subjective impression that thoughts in their minds have the characteristic ring, form, and dialogicity of speech" (p. 19).

It is not easy to confirm that a person always uses one language to think, count, write a diary, pray, write shopping lists, etc. Therefore, some aspects that contribute to the hypothesis that a bilingual person switches languages for such activities will be observed in the continuation of this paper. Firstly, we may consider the language in which bilinguals count. Pavlenko (2014) proposes specific variables that should be taken into consideration when one attempts to answer this question. The first one is L1 advantage, by which "many bilinguals acknowledge that, regardless of their current language dominance and environment, they still use their L1 for simple arithmetic operations" (p. 99). Perhaps bilinguals turn to their first language when counting because they feel more natural in that way. Another variable refers to language of instruction advantage. Pavlenko (2014, p. 99) identifies it because it appears that even though L1 was first acquired at home, it is the language learned in school that is most easily retrieved for mental operations, such as counting in this case. There is also the variable related to language dominance, where it is suggested that bilinguals use L1 for mental operations in cases when L1 is dominant, while they choose L1 less frequently when it is on the same level of dominance as some other language, and it is least used when some other language is considered dominant (Dewaele, 2004b, referred to in Pavlenko, 2014, p. 100). The fourth variable is called language advantage, i.e. the "advantage conferred by the language itself" (Pavlenko, 2014, p. 100). The last variable refers to the language of encoding advantage, which is associated with retrieval of numerical data (Pavlenko, 2014, p. 101). In 1998, Cook undertook a study in which the usage of languages was tested for the following purposes: self-organizational (e.g. making shopping lists); doing mental arithmetic tasks (e.g. counting or adding up); memorizing everyday information (e.g. days of the week or phone numbers); unconscious uses (e.g. dreaming); expressing emotions (e.g. happiness or sadness); non-communicative uses (e.g. talking to small babies or animals); and praying to oneself (as cited in De Guerrero, 2005, pp. 64-65).

A study of the relationship between bilingualism and identity in expressing emotions and thoughts

As was already stated, bilingualism is not an easy concept to identify; different authors' opinions are such that who counts as a bilingual is a rather loose framework. Similarly, identifying which language a bilingual person uses in the process of thinking or expressing emotions and why represents a very challenging task. Therefore, the aim of this study is to challenge the hypothesis that L1 is always the first chosen in these processes and propose that sometimes L2 is the first to be selected, or, moreover, that a combination of both languages may also appear in specific situations. The data collected and interpreted in the research conducted for the purposes of this paper might help to shed some light on the connection between individuals' language usages and emotions, as well as cognitive processes.

Methodology and research questions

As was stated above, the basic goal of this paper is to demonstrate whether participants' second language is the language preferred for expressing emotions and thoughts, and to what extent. The theoretical incentive for the design of the study's research questions has been elaborated above. In this section, the focus is placed on the elaboration of the specific type of methodology, i.e. the methodological procedure used in the study and specific research questions. In order to achieve the aim of this study, a qualitative methodology was used, i.e. the method of open-ended questions in a questionnaire. This particular methodology "does not provide the defining characteristics of qualitative data. It is the nature of the data produced that is the crucial issue" (Denscombe, 2007, p. 286). In other words, unlike quantitative methods whose primary aim is to confirm a single or set of hypotheses related to an issue, qualitative methods aim to provide an in-depth exploration of an issue as they exhibit more flexibility in classifying informants' feedback. Additionally, unlike quantitative methods, which focus mainly on presenting a community's characteristics, quantitative methods stress an individual's viewpoint. Knowing that qualitative methods offer the basis for understanding a specific topic, the use of open-ended questions is in this case relevant, as the experiences of bilingual participants are questioned (see the Appendix). The questions match the participants' competencies, and all participants answer the same questions. Due to the nature of open-ended questions, the participants have more freedom in their responses, which is also important regarding the aim of the study. Although the application of this type of questions has certain disadvantages, primarily the fact that the research has to pay more attention to how data are analyzed, it is still a valuable method for gaining insight into a bilingual's mind. Thus, the collected material "is more likely to reflect the full richness and complexity of the views held by the respondent. Respondents are allowed space to express themselves in their own words" (Denscombe, 2007, p. 166). Following the qualitative presentation of participants' responses to open-ended questions, which represents the basis of the applied methodological apparatus in this paper, there is also a descriptive and a quantitative presentation of the occurrences of usage of either L1, L2, or both languages in expressing emotions and in different types of cognitive processes for all participants.

As far as the main types of information gathered are concerned, we may speak of those related to "facts" and those related to "opinions;" these two should be evidently structured and treated differently by the researcher (Denscombe, 2007, p. 155). The beginning of the questionnaire consists of introductory questions, which demand some basic information about the participants including the usage of their languages, and are presented later on. The second part of the questionnaire is made up of questions strictly connected to the topic of expressing emotions and cognitive process. The structure of the questionnaire is in correspondence with the research questions which are, in turn, aligned with the overall goal of the study. Research questions relate to identifying instances of bilinguals using L1, L2, or both languages when expressing emotions or engaging in specific cognitive processes and they have to do with the factors that might be taken into consideration in such identifications, as proposed by authors such as Pavlenko (e.g. age of acquisition, context of acquisition, personal history, language dominance, language proficiency, language of instruction, etc.). Specifically, they aim to answer questions about which language is viewed as "more emotional;" which language is used to express different types of emotions or retelling a stressful event; and which language is involved in processes of thinking, counting, converting currency, writing diaries, writing shopping lists, and writing notes/lists.

The research was conducted in March 2015 on ten anonymous participants with their acceptance of participation in the research. The data collected was used exclusively for the purposes of this research. The participants' statements presented in this paper have been translated by the authors as the research was conducted in Croatian. During the analysis of the questions included in the questionnaire, not all participants' answers were used for every question due to the limitations related to the length of this paper.

Results and analysis

Participants and their sociolinguistic environment

Before presenting and interpreting the results of the research concerning emotions and cognitive processes, the participants should be contextualized in their sociolinguistic environment. In this paper, sociolinguistic environment refers to participants' age, chronological order in acquiring languages, and the environment in which languages were acquired, which is elaborated on in the continuation of the paper. This placement is necessary because "the sociolinguistic and biographical contexts in which any bilingual has learned and spoken his/her two languages are critical to understanding the role of bilingualism in affective experience" (Koven, 2006, p. 86).

As was already stated, the research consists of two types of questions. The first type concerns introductory questions that are explained in this part of the paper. The second part deals more strictly with emotions and cognitive processes. Introductory questions include information about age, chronological order in acquiring languages, and the environment in which languages were acquired. The questions in this group also considered the age of the participants when they came in contact with their L2 for the first time and in which surroundings, as well as the age at which they began to use it actively. As far as the participants' first languages are concerned, four consider Croatian to be their L1, two German, two English, one Hungarian, and one Italian. As for their L2s, for five of them it is Croatian, for four it is German, and for one both German and Spanish. The questions about which language was used in their school education and which language they use at home with their families are useful in order to place the participants in their sociolinguistic environment. The research included ten participants of different ages (from 21 to 46). There were nine female participants and one male. Majority of the participants began to use their second language during early childhood.

"I was in contact with my second language from the first year of my life, but began to use it actively when I was three or four" (P4, 23).1

"When I was one year old, my family moved to Germany, and I began to use it actively from the age of three" (P7, 24).

"I grew up in Switzerland and my parents spoke only Croatian with us from the beginning. I began to learn Swiss in the kindergarten (since I was four)" (P8, 24).

"I acquired both languages at the same time as I was born in Switzerland, but at home I spoke Croatian with my parents" (P10, 23).

Also, four participants began to use their second language actively when they were ten or older, due to moving to another country, although three of them were in contact with their second language from early childhood because they spent summer holidays in the country to which they moved later on.

"During my childhood, I was in contact with Croatian; I could understand it, but I could not speak Croatian. I began to use it when I was 14. At home and during the summer holidays spent at my grandma's, I was in contact with Croatian, but later due to moving I had to start using it in my everyday life" (P6, 21).

"I was in contact with my second language since I was 10 but began to use it actively since I was 12. When I came to live to Croatia, I began to use Croatian actively, mostly in school" (P9, 21).

Only one participant was not in contact with the second language until the age of 10, when she moved to another country. Furthermore, as the language of their school education is concerned, four of them had their school education conducted in their L1, while six participants first had their education in L1, but due to moving to another country, it changed to another language, which is today their L2.

"Half and half... during my elementary education, I lived in Italy, but I went to high school in Croatia" (P6, 21).

"1st-6th grade: English; 6th-8th grade: Croatian, and 1st-4th class of high school: Croatian" (P9, 21).

Regarding the language spoken at home, five participants usually speak their L1 and three of them usually switch languages, mostly depending on the situation.

"Croatian with my parents, but both Croatian and Swiss with my brothers" (P8, 24).

Two participants tend to speak one language, but sometimes switch to the other. The difference is that one participant usually uses L1 and the second one now L2.

"At home I speak English with my parents, with my sister also usually English, but sometimes we speak Croatian" (P5, 24).

This participant's L1 is English and L2 Croatian.

"It depends on the topic of the conversation, but now usually Croatian" (P6, 21).

(This participant's L1 is Italian and L2 Croatian).

The results concerning the situations in which they use either language are various and discussed in the latter part of this paper. On the basis of the results so far, we can conclude that all participants were in contact with their L2 since their childhood, though some began to use it in the early years of their childhood and some later. They use both their L1 and L2 on daily basis, which is of great importance for further analysis. The observations made about the age of participants' exposure to L2 are relevant for two reasons. Firstly, they contribute to the understanding of participants' choice of either L1, L2, or both, which is to be presented in subsequent parts of the paper. Secondly, these observations are important because they contribute to understanding the participants' overall identity. Namely, if most of the participants were exposed to their L2s early in childhood, this means that they should not have problems expressing emotions or dealing with cognitive processes in either of the languages. In other words, the choice of either L1 or L2 in some cases seems more a matter of the participants' preference for expressing something that is more intimate and connected with their "core" identity by using the language that actually represents that core identity. On the other hand, in other types of situations the motivations behind choosing either L1 or L2 might be quite different. This will be demonstrated in the following parts of the paper by the presentation of informants' responses concerning the usage of different languages in the expression of emotions and in cognitive processes.

Analysis of results concerning emotions

In this part of the paper, we will focus on the ways in which bilingual individuals use their languages to express emotions. Grosjean (2010) proposes it is a myth that "bilinguals express their emotions in their first language", especially in cases of simultaneous acquisition of the languages, but, to a great extent, also in cases of successive acquisition (p. 129). Furthermore, Pavlenko (2006) poses the following question: "Do bi- and multi- linguals sometimes feel like different people when speaking different languages?" (p. 1). Such a question clearly emphasizes the complexity of the area of study, but also the extent to which this type of analysis is both a linguistic and a psychological issue. Only by taking these approaches into consideration can we conceive of how difficult it is to determine which language bilinguals use when they express emotions. Nevertheless, the focus here is on the data collected from the study, that is, on the participants' personal experiences. The results are analyzed to determine if the factors that influence emotionality are consistent with those presented by Aneta Pavlenko (2005).

Age of acquisition

The first factor is the age of acquisition of a particular language, by which the language acquired earlier is assumed to be more emotional (Dewaele, 2004c, as cited in Pavlenko, 2005, p. 185). Based on the results of the undertaken research, eight out of ten participants answered that they felt their mother tongue to be more emotional, even though majority was introduced to their L2 already in their childhood. Examples in this sense include the following:

"Hungarian is my more emotional language because it is my mother tongue. I started acquiring it since childhood and my education was in Hungarian" (P3, 46).

"I think English is emotionally closer to me because it is the language of my childhood. I feel more comfortable in that language. I do not have to think whether I will make a grammatical mistake or use some wrong word and I do not have to think about the vocabulary" (P5, 24).

Context of acquisition

Context of acquisition means the L2 can have emotional value due to the context in which it is learned. This is a very important concept and may be taken as a general principle considering the fact that among the informants, there is a notable pattern according to which emotional contexts of language learning and use promote strong emotional resonances. By referring to Dewaele (2004c), Pavlenko (2005) writes that formal contexts have a strong influence in considering emotion words as less emotional (p. 185). Also, if emotion words are learned in more private contexts, individuals may feel that these are closer and more significant to them (Pavlenko, 2004, as cited in Pavlenko, 2005, p. 185). One participant, whose L1 is German, stated that she was able to utter "I love you" in Croatian with more feelings because this participant's first love comes from Croatia:

"In Croatian, but I think that is more because I met my first and true love in Croatia. Therefore, the sentence 'I love you' was uttered for the first time in Croatian and was honest and made sense. I connect that sentence with my first love; therefore it does not have the same meaning in German" (P10, 23).

Another research question that can be connected to this factor is whether the participants have or had a partner whose dominant language is not their dominant language. Due to the small number of participants, more information about their experience could not be collected.

"In the beginning as I used English, it had more value to speak about emotions in English. But now after we have been together for several years, I am used to that, and I talk in Croatian to him. The more emotional we are, the more I can give of myself, so to speak, in Croatian. Maybe it is also because I know that it is his emotionally closer language" (P5, 24).

Perhaps this leads to the conclusion that if this participant had not had a partner whose dominant language was not the same as hers, she could not express her emotions freely in Croatian, as perhaps she would not have developed that vocabulary.

Personal history of trauma, stress, or violence

The third criterion is personal history of trauma, stress, and violence (Pavlenko, 2005, pp. 185-186). Pavlenko (2005) suggests that it is common to think about some negative experiences in the language that is emotionally further in order for speakers to distance themselves from negative feelings (pp. 185-186). On the other hand, she also makes reference to Brison (2002), who experienced trauma, and believes that it is to the same extent uncomfortable to speak about it in any language as it is embedded in the person's psyche (as referred to in Pavlenko, 2005, p. 186). Varying answers were given to the question regarding which language they think it is easier for them to use to retell some negative experience or trauma. Some answered that it does not make any difference, while some claimed it is easier in their mother tongue because they express themselves more easily.

"For me it is easier to talk about everything in Swiss because sometimes I lack words in Croatian. But I have noticed that that has changed since I have been living in Croatia" (P8, 24).

"I think it is easier in the first one, especially if it happened when I was little and when I was thinking in English. But if something happened in the Croatian surrounding, then I cannot translate some words, therefore it is easier to retell it in Croatian" (P5, 24).

Language dominance

The fourth criterion is language dominance. Pavlenko (2005) argued that people express their emotions better in their dominant language even though it may not be their first acquired language (p. 186). The great majority of the participants answered that they can express their emotions better in their dominant language, but in this research, it turned out that their dominant language is also their mother tongue.

"I believe that when I express myself in English my words have more value. When I spoke Croatian in the beginning, I felt as it is something strange, as if I spoke some strange words that did not mean what they were actually supposed to mean" (P5, 24).

"In Italian because I can express myself easier and without fear of making a mistake" (P6, 21).

One participant answered differently from the others:

"It all depends where I am and for how long. When I come to Switzerland, I need about one week to switch to that language and then I automatically express myself better in that language. As I am now in Croatia, I express myself better and easier in Croatian" (P10, 23).

We can see that for this participant it could be more a question of surroundings while both of her languages could be equally dominant.

Word type

The following criterion is the type of word. Pavlenko (2005, p. 186) states that for instance, "taboo words elicited strong reactions in both languages" (L1, L2), "although (...) stronger in L1", based on statements by Dewaele (2004a, 2004c) Harris et al. (2003), Harris (2004) and Harris et al. (2006). Nevertheless, she also includes terms of endearment in this category, stating that the views about these are very different.

"It depends on which word I use in which surrounding more, that is the reason in which language I will remember some word faster. For example, if it is about nature, the word would come to me faster in Hungarian, because I used to study a lot of words connected to that in school, in Hungarian. If I speak about subjects connected with faith and religion, the word would come to me faster in Croatian because I use those words more in the Croatian surrounding" (P3, 46).

Language proficiency

The last criterion refers to language proficiency. In this context, it is important to mention a study conducted by Rintell (1984), which included native speakers of different languages whose L2 was English, and whose results in evaluating emotional intensity in English were largely influenced by their language proficiency in the L2 (as referred to in Dewaele, 2006, pp. 123-124).

Referring to Dewaele (2004b), Pavlenko (2005, p. 186) writes that some bilinguals find their L1 more emotional, even though they have reached higher proficiency in some other language. However, some speakers who have low L2 proficiency react strongly to some words in their second language, e.g. swear words; it is more a case of their "performance of affect" (Pavlenko, 2005, p. 186). Thus, in this context, we may differentiate between general language proficiency in L2 and the extent of knowledge of individual vocabulary items in L2. The following example demonstrates that the choice of L2 to express emotions is primarily a matter of the extent of knowledge of swear words in L2, and not necessarily a matter of general language proficiency in that language.

"I express my anger in Croatian because it has more swear words" (P10, 23).

This participant's L1 is German and L2 is Croatian.

Furthermore, there is also the issue of an individual's inability to express their emotions in L2 due to the lack of linguistic content in that language. For instance, in one language, there is one lexeme denoting anger, while in the other there may be a few of them, each different in meaning. That leads to issues related to conceptual and structural equivalents (Pavlenko, 2014, p. 257).

It is also important that there may be significant changes in cognitive representations of the category of emotions. From the point of view of analyzing such a category or semantic field in its changes, these changes may include different cognitive processes, such as "category restructuring, expansion, and narrowing, as well as internalization of new emotion categories that do not have a counterpart in the L1" (Pavlenko, 2014, p. 253).

Based on the data collected for the purposes of this research, the participants were unanimous in stating that there is a problem of vocabulary when it comes to expressing themselves in a certain way in their non-dominant language.

"Yes. It is hard to talk freely and be myself when I have to think about the words and about the vocabulary. And often in difficult moments I lose words and I am not able to put together one Croatian sentence" (P5, 24).

"Yes, it does. Sometimes, because my vocabulary in Croatian is restricted, it is tough for me to express myself" (P9, 21).

Nevertheless, as far as expressing anger is concerned, participants answered differently to the question regarding which language is easier for them to use to express anger and whether it is easier for them to express anger towards the person who shares their L1. Some said it was their dominant language in which it is easier to express anger:

"Yes, it is my dominant language. I feel like I am more into the conversation" (P2, 31).

"The brain functions in that way. As if that language has 'ingrown' or 'possessed' more territory in the brain. As if that inner being, personality, is connected only to one language. Even though it is not a problem to express anger in my L2, I felt it more spontaneous and uncontrolled in my mother tongue. In the second language it is more 'controlled'" (P3, 46).

"For me the problem is that when I am angry I do not want to think about the words because then I get lost and cannot express myself" (P5, 24).

Furthermore, some said they use a mixture of the languages:

"Usually in Croatian, but sometimes I use some German words" (P7, 24).

Another participant answered that for her the easiest way to express anger is when a person she is angry with speaks both English and Croatian (those are the participant's L1 and L2, respectively).

"I think so. For instance, it is easier for me to yell at somebody who understands both English and Croatian because I can express myself easier" (P9, 21).

Some participants stated that it does not really matter in which language they express anger. According to some, this is because they consider they do not have the problem of a lack of vocabulary, and for others because for them the expression plays a more important role than words do.

"I believe I can express anger in the same way in all languages. I do not think it is a question of the vocabulary; I think it depends on the situation" (P4, 23).

"I think that it can be seen when somebody is angry even without too many words. That is why I consider that vocabulary in that situation is not that important at all; it is important to show some emotion" (P8, 24).

"It is not that much in the lack of the vocabulary. It all depends in which language one is thinking at the moment. Because when I speak in my L2 or if I want to express myself in some special way, automatically the sentences come to me in Croatian. And due to the fact that Croatian grammar and sentence are different from German ones, it can happen that at that moment I do not express myself in the way I would in Croatian" (P10, 23).

It is interesting to note that all participants said that it was not a problem for them to express anger in their L2, but that some preferred their L1 because they can express themselves without thinking. Finally, this could also be connected with the level of their proficiency in L2.

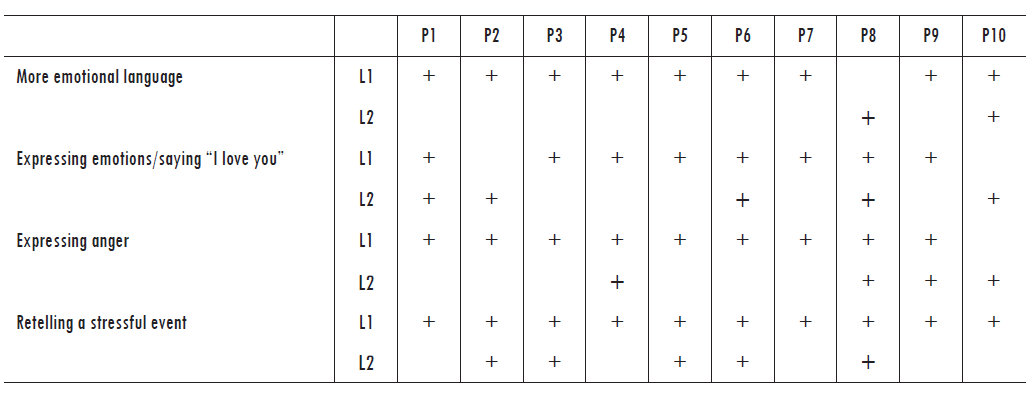

After the qualitative analysis of the participants' responses, the following refers to the second part of the analysis, i.e. the quantitative analysis. Table 1 presents the usage of a particular language in the expression of emotions, as well as a descriptive presentation of participants' responses.

The first indication investigates which language they find more emotional. Eight of the ten participants answered that they find their L1 to be more emotional, whereas one participant finds both languages similarly emotional (P10, 23), and for one (P8, 24), her L2 is more emotional. This participant's answer could be related to the fact that even though she lives in Croatia (Croatian is her L1) now, she still expresses herself emotionally better in her L2 since her school education was conducted in that language and she lived part of her life in that country.

Five participants stated that the sentence "I love you" has deeper and more sincere meaning for them in their L1 and three of them stated that it does not depend on a language. It may be the case that L1 and L2 are equally dominant for them. However, one participant (P2, 31) stated that this sentence has deeper meaning in her L2, possibly connected to the fact that she lives in Croatia (Croatian is her L2) and that she has a partner whose L1 is Croatian. Another participant (P10, 23) answered that this sentence has more value for her in her L2, as she uttered it for the first time in her L2. Six informants express anger more easily in their L1, one in L2, and three can express themselves the best when using both languages. One participant (P10, 23) finds it easier to express anger in her L2 due to the fact that Croatian (her L2) has more swear words. As far as retelling stressful events is concerned, half the participants can express themselves better in L1, whereas the other half would use both languages in order to fully express themselves.

Analysis of results concerning cognitive process.

The question of how bilinguals process thoughts is raised often. Linguists, as well as psychologists, are curious about whether bilinguals process thoughts in the same way as monolinguals (unilinguals) or differently. It seems that we may speak only of data differences, and not those related to the actual cognitive processing. Namely, "the difference is one of degree; it concerns only the content of representations (i.e., the specific combination of conceptual features), not the way concepts are acquired, formed, used or stored" (Paradis, 2007, pp. 13-14). Nevertheless, one must be aware of the fact that bilinguals have two languages included in the process of thinking: "In the bilingual process, we assume that two languages are expected to become involved in the cognitive process, even in the prelinguistic organization level, but more clearly so from the first level of linguistic organization on" (Javier, 2007, p. 30).

The part of the research questions dealing with cognitive processes is presented in order to relate the collected data to the four criteria concerning counting that differentiate bilinguals from monolinguals. The criteria are proposed by Pavlenko (2014) and discussed in what follows. Apart from counting, there are other activities connected with thinking, such as writing a diary, schedule, shopping list, everyday notes, etc., which are also included in the analysis of the results concerning cognitive processes.

To begin with the criteria, the first proposes that bilinguals would more often choose their L1 for counting even if they have reached a high proficiency in their L2 (Pavlenko, 2014, p. 99). Seven participants always count in their L1, while three of them switch from one language to another.

"I always, but really always, count in Italian. I cannot explain it even to myself" (P6, 21).

"I count in Hungarian. Even if Croats are around me I count in Hungarian, even when I do so out loud" (P3, 46).

"Always in German, numbers confuse me in Croatian" (P2, 31).

"As a rule, I count in English, but if people are around me, then I count in Croatian or when I was at school and we learned something in math in Croatian, so I would count in my head in Croatian while doing my homework" (P5, 24).

The following criterion is the language of instruction advantage (Pavlenko, 2014, p. 99). It means that it is likely for a person to think in the language of their education, even if that is not their L1. As a matter of a fact, all participants, except one, claim to count in language of their early education.

"I count in Croatian but according to the German principle as I learned there" (P10, 23). (This participant's L2 is Croatian. It is also clear that this participant does not count strictly in L2 but uses the principle thought in L1 in early education).

The last two criteria refer to language dominance and language advantage (Pavlenko, 2014, p. 100). Pavlenko (2014, p. 100) writes that a particular language would be chosen for counting if it is dominant in a particular context or due to the person's longer socialization in that society. This can be attested by a participant's answer (P5, 24), who said that she would count in Croatian (which is her L2) while doing her homework, as she learned it in Croatian at school, while her L1 is actually English. Another participant (P10, 23) stated that she counted in Croatian but by using the counting rules learned in Switzerland. The conclusion arises that this participant's dominant language could be Croatian, but the rule she learned in Switzerland has the advantage, even though she lives in Croatia now. Another participant's answer was the following:

"I count in Swiss. Maybe sometimes in Croatian, but it is more unconscious; for example, sometimes when I am in the store or bank. I think it is connected to the fact that I live in Croatia now" (P8, 24).

In this case, it is evident that L2 takes over sometimes.

Regarding the process of thinking in general, participants mostly think in their dominant language because they feel more secure and natural that way. Yet there are situations when they would switch to their L2, and that is due to their surroundings or when they are studying in their L2 and it becomes normal for them to think or express themselves in that language. Here we present answers to the question concerned with the choice of the language generally used for thinking.

"99% in dominant language. I combine contents easier. Preparing for classes is in German. It gives me security that that language is a part of me even though I do not live there anymore" (P2, 31).

"As a rule, I think in English. But, there are moments when I think in Croatian. For instance, if I think about some material I studied in Croatian and I have wider vocabulary concerning that, then I would think in Croatian or even when I think about some conversation that was in Croatian. When I pray or count, then it is in English" (P5, 24).

"I think in Swiss a lot, but I have begun to think in Croatian as well. Since I moved back to Croatia, I have met new people and found myself in new situations. If I talk to somebody in Croatian, then I would remember that person later in Croatian and I would think in Croatian. But I do not consider those to be special situations, it simply depends who it is about and in which language the conversation was. In general, when I think about something, and it does not include a particular person, it is mostly in Swiss" (P8, 24).

"It depends on the situation I am in. When I think about something connected to the university, then I think in Croatian, but in general I mostly think in English" (P9, 21).

We will now turn to Cook's (1998) study introduced by De Guerrero. This study was explained previously in this paper, and its aim was to find out which language was used for internal purposes (as referred to in De Guerrero, 2005, pp. 64-65). This study serves as a framework for some questions included in the questionnaire used for the purposes of this study.

One question was concerned with converting money from one currency to another. The participants were supposed to state which language they used when they had to convert the price of something to a different currency. Almost all participants answered that they would use their L1 for this particular purpose.

"German...because I recalculate in Euros" (P2, 30).

"Hungarian. I am sure I will not make a mistake and I am more concentrated" (P3, 46).

"Croatian because I count faster in it" (P4, 23).

"I count everything automatically in Swiss Francs, never in Euros. It is my habit and whenever I came in Croatia for holidays, I would always convert in Swiss Francs" (P10, 23).

One possible explanation for the usage of German for converting into Euros could be the fact that the Euro is the currency used in Germany and German is this participant's L1. Nevertheless, another participant, who grew up in Switzerland, answered that she conceptualizes everything in Swiss Francs. Therefore, the specific currency used in a particular country in which the person was brought up is the one that is automatically chosen.

However, one participant answered that she would use her L2 and considers it to be more natural.

"I would use Swiss because it is more natural to me and I think I would convert it faster" (P8, 24).

Furthermore, there was a question related to writing diaries. Those who write diaries were supposed to answer in which language they do so, and the answers were quite diverse.

"Always in German. I express myself best in that language" (P10, 23).

"A few years ago I began to write a diary in Croatian as I wanted to practice how to express myself in Croatian and then I continued to write in Croatian, but when it is too late or when I am nervous I write in English without thinking, and only later I find out I wrote in the wrong language" (P5, 24).

"I don't write a diary but I write down my thoughts. I write in both languages. I think that when it is more personal, my texts are written in Hungarian. If it is something general or a record of an event or notes from a lecture, then it would be in Croatian" (P3, 46).

The last question was concerned with writing all kinds of lists (shopping lists, to-do lists, daily schedules, and school schedules). Six participants stated that they would use both languages, sometimes a mixture of both languages, and sometimes one language for one kind of list and the other for a different kind of list.

"If the list has to do with the activity I will do myself -it is in Hungarian. Sometimes if the lists, duties, or schedules are linked to some other people, then I write in Croatian" (P3, 46).

"Most of my lists are mixed. Even when I make a schedule, I begin writing the days of the week in Croatian and unconsciously, after the second or third day, I end up writing in English. But the subjects written in school schedule are always in Croatian. To-do lists are also mixed and even when I write a reminder in the calendar, it is mixed. One day I write 'rođendan' [birthday] and the other day I write 'bday'" (P5, 24).

"I write shopping lists and school schedules in Croatian, but to-do lists in Italian. Sometimes even I myself do not understand why I chose that particular language, more often it is easier in Italian, it seems more natural" (P6, 21).

"Croatian because I live in Croatia. But I see what a big influence German has on me. For instance, I would hardly solve a crossword in Croatian because I do not know that many words in standard Croatian. But in German I would solve it without problems. German is a nicer and a more natural language to me. I personally consider German to be my mother tongue" (P10, 23).

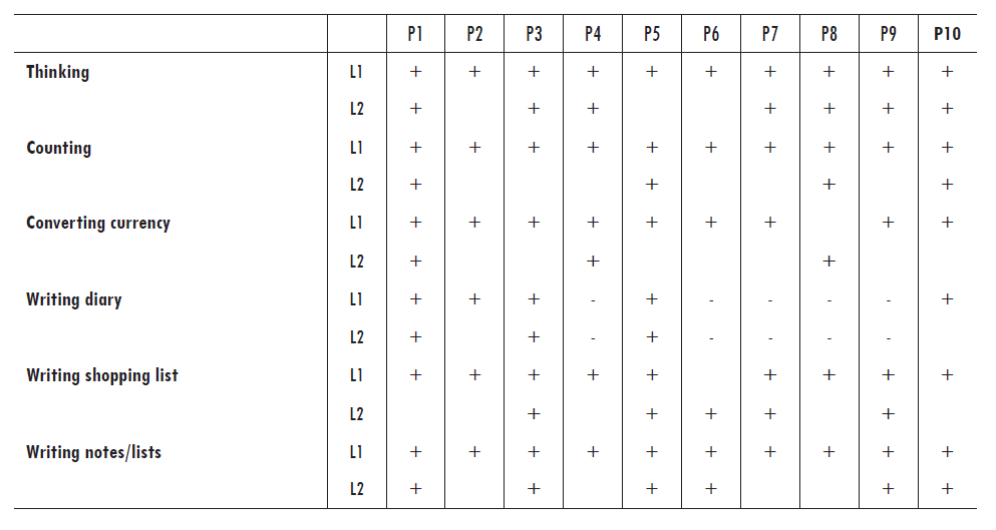

Table 2 provides data on activities that include information about the usage of the particular language by the informants. The first process is thinking, and three participants responded that they think in their L1, whereas the majority use a mixture of both languages. As the informants answered, it may usually depend on the topic they think about, people they think about, etc. On the other hand, the majority answered that they would unconsciously use their L1 for counting, and four of informants said they use both languages. For converting currency, the majority would use their L1 again, and two of them use both languages. However, it is interesting to note that one participant (P8, 24) uses her L2 for converting currency, but this same participant uses both languages for counting. These results may be compared to Pavlenko's claim related to the L1 advantage variable and her own experience with arithmetic operations (2014, p. 99).

Furthermore, five participants keep diaries, and among them two write in their L1 and three use both languages in order to express their thoughts. Writing lists is divided into two separate sections, the first including writing shopping lists and the second, writing notes and different kinds of lists. Five participants write shopping lists in their L1, one in her L2, and four use both languages. As they responded, the mixture of languages takes place especially when some products are specifically close to each other in both languages. Lastly, six participants use both languages for writing different kinds of notes and lists, whereas four of them prefer their L1 since it comes more naturally to them when writing down their thoughts or different notes.

It has already been stated that the basic goal of this paper is to demonstrate whether participants' second language is the language preferred for expressing emotions and thoughts, and to what extent. The results presented in this analysis related to expressing emotions and cognitive processes clearly demonstrate the different patterns of participants' choices of specific language for specific purposes. In the process, Pavlenko's observations have clearly served as a helpful framework and a valuable guideline for identifying the different factors that should be taken into consideration when analyzing patterns of participants' choices of specific language for specific purposes.

Conclusion

The focus of this paper was to analyze the relationship between bilingualism and the processes of expressing emotions and thoughts. With regards to bilingualism, many authors do not have the same opinion about whom they consider to be a bilingual. For some, a bilingual person is someone who has basic competence in the second language, while for others it is a person who has a native-like competence in the second language. Furthermore, there are also different views among scholars in proposals of specific criteria suitable for qualifying someone as a bilingual.

The basic goal of the analysis conducted was to test the different factors influencing the choice of languages used for different types of activities related to expressing emotions and thoughts. This paper represents an attempt to demonstrate that L1 is not always chosen first and that sometimes L2 is chosen first, or that there may even be a combination of usage of both languages in the processes analyzed. In order to support this hypothesis, a study was conducted among ten bilingual participants who were asked to answer a set of questions concerning the languages in which they express emotions and thoughts. The first part of the research dealt specifically with emotions and the second, with cognitive processes. The four criteria proposed by Pavlenko (2005) were used as a framework to identify the situations and reasons why a particular language was chosen to express emotions.

Generally, the majority of the participants considered their L1 to be more emotional. For some of them, it is only their L1 in which they can sincerely utter the sentence "I love you," but the choice of L1 is even greater when it comes to expressing anger. Nevertheless, some participants consider the usage of both languages to be the best option in order to express themselves fully. The analysis also deals with the ways in which the two languages are used by bilinguals in order to process specific actions connected with thinking, such as counting, writing a diary, schedule, shopping lists, everyday notes, etc. The results show considerable differences from one individual to another, presumably because the language acquisition process is connected with different situations and surroundings, such that in some situations, one language has dominance while in other situations, another language takes over.

In this sense, the majority thinks in both languages, depending on the situation, topic, etc. However, as far as counting and converting currency are concerned, the L1 is mostly used. Some participants responded that they are not even aware of why they choose their L1 for these actions. There are also situations in which a mixture of both languages is used, for instance in writing lists. Some lists would be written in one language while another kind of list would be in another language. Half of the participants prefer L1 when writing shopping lists, and others mix languages, mostly depending on whether the products are closely related either to their L1 or L2. Though the answers are unique for every individual, the common conclusion is that none of the participant use only one language for expressing emotions and cognitive processing.

Nevertheless, the identity of bilinguals is affected while expressing emotions and thoughts since in some situations bilinguals would choose one language, while in other situations another language would prevail. Therefore, by taking into consideration the factors analyzed, it can be stated that different factors influence the choice of a particular language and that all those factors contribute to the process of identity construction. Another important notion is that of belonging to a particular culture, or even more than one culture at the same time, which also contributes to the formation and expression of the overall identity of bilinguals. Regardless of the complexity of factors that come into play when discussing bilinguals' and biculturals' identities, and based on the presentation of the participants' responses, this paper supports the notion that the choice of different languages in performing different operations is largely affected by an array of subjective and highly personal factors. Nevertheless, the study offers a basis for validating claims that have previously been made by influential scholars in the field and on the basis of a unique sample.