Introduction

Throughout the history of English language education policy in Colombia, particular policies shifted language-learning contexts more than others did. First, General Education Law 115 of 1994 intended to provide education for all individuals (Congreso de la República de Colombia, 1994). More importantly, schools were required to guarantee foreign language studies to students and ensure that they could use that foreign language for conversation and reading purposes upon graduation (Congreso de la República de Colombia, 1994). Most schools chose English as the foreign language to teach.

Second, the development of the Basic Standards of Competences in a Foreign Language: English (hereinafter, "Standards") assisted teaching and learning environments by providing a recognizable, measurable system for language acquisition (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2006) based upon the language ability levels stated in the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) designed by the Council of Europe (2011). The expectation was that Colombian primary and secondary students would achieve a CEFR B1 level by the end of 11th grade in English and a B2/C1 level of English after university (Usma, 2009; Vélez-Rendón, 2003; Wells, 2008).

The third and current shift has been the Plan Nacional Bilingüe of the Ministry of Education (now, Colombia Bilingüe, 2014-2019) which promotes English language learning with the aim of achieving a bilingual nation in both the public and private sectors of education. This plan proposes that all students learn English by 2019. Other interventions introduced in the plan include professional development workshops for teachers, the creation of resources and materials, and strengthening the use of technology in schools (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2014).

Within the Colombian context, economic and sociocultural shifts appear to be the most relevant changes since the implementation of the newer language policies (Cárdenas, González, & Álvarez, 2010). The economic position toward the learning of English in Colombia is twofold: the perception that knowing English improves economic opportunities and therefore status, even within the country; plus, the millions of Colombian pesos toward investment at primary and secondary levels would increase equitable learning and international competition (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2014). The sociocultural position on language learning involves learners' actions and rules established within the context (Grin, 2002). Currently, while it may be that many learning contexts are struggling to meet, if not resisting, the demand for English language teaching, the status of English in Colombia has gained precedence.

Nonetheless, Colombian English language teachers and learning institutions still have much to learn from student input and value statements (López & Bernal, 2009). Even with all of the aforementioned developments and implementations, very little has affected the teaching process nor has it met the learning needs of the students. Therefore, this study intends to provide more information to help fulfill the current challenge regarding how to approach language learning classes and classroom contexts by uncovering student perceptions, beliefs and attitudes about English language learning. In this way, the interpretative results could help inform the practice of English instruction in such a way that teachers and professors influence student learning of and attitude toward English. Thus, the guiding research question for this study follows: How do students' beliefs or value statements about learning English in Colombia depict a contextual view of English language learners?

Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework review below consists of three key components: a brief summary of studies regarding beliefs about language learning and a description of the economic and sociocultural perspectives on language learning. The hope is that by combining the three, a clearer, contextual view of Colombian students' perceptions will reveal trends or areas that we, as educators of the English language, can address in our individual learning contexts.

Beliefs about language learning

According to Ellis (2002), "beliefs are both situated and dynamic. They change as a product of new situational experiences and, in particular, the attributions that learners make for their success or failure" (pp. 22-23). This section provides examples and details of three types of belief studies: normative, contextual, and metaphor analysis.

Normative studies

Normative studies consist of statistical and quantifiable answers in which results act as indicators or behaviors based on some causal relationship (Barcelos, 2000; Holliday, 1994) or trait (Wesley, 2012). The most common normative studies include the Beliefs about Language Learning Inventory (BALLI) created by Horwitz (1985). The BALLI uses five categories to classify student beliefs about language learning: foreign language aptitude, difficulty of language learning, nature of language learning, learning and communication strategies, and motivation and expectations (Horwitz, 1985).

Major findings using the BALLI instrument include beliefs regarding language aptitude, language hierarchy, and repetition (Horwitz, 1985); language aptitude, vocabulary and grammar (Horwitz, 1987); a tendency to share beliefs among cultural groups (Horwitz, 1999); and how beliefs can be exchanged between students and teachers (Kern, 1995). Other BALLI studies include comparing students based on gender. Parilah et al. (2009) demonstrate specific differences between males and females in learning difficulties and language immersion, while Jafari & Shokrpour (2012) report motivation, language learning difficulty, and language aptitude affecting the sexes differently.

One of the few normative studies of language learning beliefs in Colombia comes from Schulz (2001). She compared language learners and teachers in the US and Colombia. Schulz (2001) reports varying differences between explicit grammar teaching and corrective feedback, but very similar traditional language teaching styles.

Normative studies tend to demonstrate, descriptively, that language learning can be systematized and operationalized (Wesley, 2012) providing general concepts of the learner, learner beliefs, and other classifiable traits of language learners and learning (Wesley, 2012). Therefore, these types of studies only provide a narrow view of who language learners are and in what ways they are capable of learning a second language. Though there were some differences, most of the studies reflect similar conclusions to Horwitz (1988) in that beliefs toward language learning resonate regardless of a student's cultural disposition.

Contextual studies

The second type of belief study is contextual studies. Contextual studies examine student perspectives and changes in the same through content analysis (Borg, 2011; Mercer, 2011). The disadvantage of such studies, however, is that small scale studies are difficult to generalize to an entire population (Barcelos, 2006). According to Barcelos (2006), contextual studies have occurred in two major phases: through the mid-1990s and early 2000s (Allen, 1996; Barcelos, 2001; Miller & Ginsberg, 1995) and later with Borg (2011), Mercer (2011), and Peng (2011).

Miller and Ginsberg (1995), in a study of American graduate and undergraduate students in Russia, discovered that student beliefs were more focused on vocabulary, syntax, and speaking correctly. There was also an important discovery that learning for these students was "doing" (p. 306) and a "journey" (p. 310). Allen (1996) observed one Libyan student in Canada through interviews and a diary (journal) study. He discovered that the student shifted beliefs toward the teacher's ideas and influence. Likewise, Barcelos' (2001) study in Brazil revealed that previous learning experiences impact learning beliefs, but do not necessarily demonstrate how those experiences contribute to student actions. All of these studies exemplify the importance of understanding beliefs, but they do not necessarily represent a full understanding of the learners in general.

The second phase of contextual studies implied that beliefs are situational and complex (Mercer, 2011), shifting (Peng, 2011), and influenced by reflection and contextual affordances (Borg, 2011; Peng, 2011). Using journals and interviews with regard to learning beliefs and self-perception as a learner, Mercer (2011) found in Austria that beliefs are difficult to separate and change. Peng (2011) studied a first-year student in a university to determine how, if at all, beliefs changed from language learning in high school to language learning in university. Peng (2011) found that classroom affordances can help students change perspectives and beliefs, thus demonstrating that learning and the learner do respond to context. Furthermore, Borg (2011) focused on in-service English language teachers in the UK. He found that when knowledge changes, there is a shift to better, more reflective teacher growth and beliefs. Through discussion and articulation of beliefs, it is possible to help teachers improve their classroom practices.

Metaphor analysis studies

The use of metaphor analysis studies has provided information from students to help determine beliefs about language learning through identifying expressions, words, or other dialogic descriptions. Determining categories required identifying particular influences or rating beliefs toward language learning (Ellis, 2008). In these cases, attitudes, learning characteristics and perceptual mismatches need consideration. Wan, Low, and Li (2011) examined student and teacher trainer beliefs about the role of the teacher in the language classroom. The study revealed teacher roles such as nurturer, devotee, and provider. However, mismatches between the studied groups demonstrated differing roles in such categories as cultural transmitter and authority figure. These findings established how powerful a teacher's role is envisioned by students and just how student beliefs and perceptions become affected by that role.

Economic perspective and language learning

Grin (2002) states that "languages are not seen only as elements of identity or as potentially valuable skills, but as a set of linguistic attributes which ... together influence actors socioeconomic status" (p. 13). There are three particular areas of interest regarding economic effects. The first relates to the economics of language learning and its effect. The second idea represents how the nature of language skills may characterize an area in which there could be a profitable investment. The final idea considers that language is both a set of linguistic attributes and influence socioeconomically (Grin, 2002). Within this framework, we can look at English language learning in Colombia accordingly.

Language and effects

For the purposes of this study, the perspective of language learning and its effect emanates from the viewpoint of English as the "essential target language." Taking into consideration the history of both English language teaching and learning in Colombia, perspectives have blended in such a way that knowing English creates the idea of economic power and status.

Throughout the years, English has become the language of business, technology, politics, and intercultural understanding (Guerrero, 2010). The teaching of English is widespread throughout the world, and in Colombia it is considered essential to succeed in a globalized world (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2006), which results in English learning shifting the focus to those cultures that speak English. There are particular strategic alliances that help promote English education throughout the country (e.g., British Council, Ministry of Education, and other commercial programs) (Guerrero, 2010), which produce the illusion that English is necessary to prosper. This idea has filtered through the educational sectors for decades (Guerrero, 2010; Wells, 2008) and may be hindering other relevant learning processes.

A principal critique, however, involved with English education is the imposition of the language on indigenous and Afro-Caribbean cultures within the country (Guerrero, 2009). Learning English is not necessarily a priority for these particular regions and cultures, but throughout the years, it has become noticeable that power belongs to the type of language being used globally and, in this case, learned; thus, the learning of English ultimately marginalizes the less popular or "powerless" language groups (Guerrero, 2009).

Nature of language skills

The idea that learning English skills as a profitable investment resounds throughout government policy; however, because of the geopolitical population distribution throughout the country, equitable diffusion that ensures attainment of these skills is still limited (Guerrero, 2010). The rural towns and "pueblos" have both less of a need for English and a lack of resources (including language teachers) to help students acquire English skills. Gómez Campo and Celis Giraldo (2009) have noted particular policies that established special admission programs for universities, scholarships, and grants for lower income families, but there is still a large demand in the market that is not being met. Also, transportation, personal health and safety, food and responsibilities within the home affect the learning of the English language (Guerrero, 2010) in that they impede a student's development, educational process, and economic growth.

Linguistic attributes and influence

The final ideas considers both the language's attributes and its influence on socioeconomic power. English language acquisition is considered a skill from which power and earning differences are derived; therefore, the market and market value are what drive success or failure (Grin, 2002). Regarding Colombian perspectives of economics and English language learning, there is a long way to go for such attainment.

Both the aforementioned Standards and the Colombia Bilingüe program promote the learning of English for better job opportunities both inside and outside the country (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2006). In terms of perceptions and influence, the British Council (2015) surveyed students and employers and found that students recognize English as important for university studies and employment prospects, and that they consider it mandatory rather than a choice. In contrast, students also reported that the courses are expensive and they have few resources to access the language and little time to learn it. Some reported no need to learn the language. Seventy percent of the employers surveyed reported that English was an important skill for hiring purposes (British Council, 2015).

Sociocultural perspective and language learning

Sociocultural perspectives examine and try to understand human behavior and development through the particular rules of social groups and the contexts in which they belong. Vygotsky (1978) reminds us that social context plays a key role in shaping learners' cognitive and social behavior. The actions that a learner does or does not choose cannot be understood completely if the context is not taken into consideration (Bourdieu, 1991). In a context such as Colombia, the social system influences the way a learner accepts and chooses his or her foreign language learning experience (Wells, 2008).

According to Bandura (1997), learning is controlled externally, and in Colombia, there is a tendency to "operationalize" the target language content (Wesley, 2012). Students' intrinsic and extrinsic tendencies and behaviors develop based on the constructs of the social context in which they are involved. Thus, the motivation to learn a second language, or anything else, is embedded in students' choices, intensity and dedication, and in the value of what is to be learned (Dörnyei, 2009). For the purposes of this study, two particular sociocultural areas are the focus: the actions exhibited by students that facilitate or constrain learning, and the rules that influence those actions.

Social context ideas of learning English

As demonstrated in the discussion on economic factors, the act of learning English as a foreign language comes from stipulated or mandated language policies that determine learner needs for the language to improve the economic development of the country (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2014). Once developed, the Standards determined the ability ranges for all levels of education within Colombia, and these CEFR levels help determine content and learning within each level of schooling. English language learning programs in the country typically report constructivist points of view in which language knowledge is built through sociocultural activities, but in reality, few schools have access to resources that would empower such learning experiences. Language-learning environments should provide meaningful and appropriate learning for students that leads not only to the development of language skills, but also general knowledge and "know how" (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2006).

Actions for learning

Jang and Jiménez (2011) found that the quantity and quality of sociocultural experiences within certain classroom environments limit student linguistic development, thus limiting general learning through either the applied rules or understanding of the target culture and language. Limitations in Colombia include

lack of linguistic knowledge,

little understanding of sociocultural approaches to language learning (though institutional plans declare that such approaches are used), and

a strong belief that exposure to language and practice will improve students' overall language acquisition (British Council, 2015).

Classrooms in the Colombian context, then, may need to help create learning communities that not only focus on the value of learning English as an important skill in and of itself, but also see learning as a way to communicate knowledge and "know-how" to others in a meaningful way. This would include providing opportunities for students to identify the sociocultural needs of a community and the means to adapt or change beliefs and attitudes accordingly. In this sense, the actions students choose will reflect not only their ideas regarding professional and economic development, but also their personal purposes for learning English.

In summary, for the purposes of this study, the combination of student beliefs about learning English and the economic and sociocultural perspectives of language learning guide the inquiry. Normative results inform this study concerning the aspects of students' cultural dispositions and beliefs about language learning. Contextual studies reveal that context and situational affordances could encourage shifts in beliefs, and the metaphor analyses show that understanding positions and attitudes through words and demonstrations could inform what teachers and learners believe about language learning. The economic perspective, through the lenses of ethnicity, language skills and influence, reiterates the need to define English language learning needs through the perceptions of the students in our specific contexts. Student opinions and beliefs about English language learning are still under-researched and may be found not to hold all economic ideals. The sociocultural perspective, through the lenses of rules and actions taken or not taken, will help provide information regarding the perspectives of students' language learning experiences and actions.

Method

This qualitative, interpretative case study stems from information provided by a larger study (Bailey, 2013), and was designed around the convergence of three research areas: beliefs about language learning, and economic and sociocultural issues surrounding the language-learning context. By returning to all the self-reported, qualitative data provided by students from the larger study (see Appendixes 1 and 2), this research offers an interpretative view of how students perceive English language learning in their particular context. The study also offers curriculum planners, instructors, and professional development providers an idea of how the reality of language learning is changing in Colombia. The importance of reflecting upon ideas through different lenses may provide innovative means for teaching language.

Participants

Fifty university student participants from all levels of English and all socio-economic backgrounds willingly answered three questions regarding their beliefs about language learning from a longer questionnaire provided to them (see Appendix 1). The student population was 312 students, representing a sample factor ratio of 6:1 to the population of 2,002 students in the English program; the fifty students involved in this study represent a sample factor ratio of 6:1 of the 312 participating students (Lagares Barreiro & Puerto Albandoz, 2001), thus providing a representative sample for discussion.

Demographic information was collected for use with the quantitative data collected for the larger study (Bailey, 2013), but the qualitative data was random and the demographic information was not applied because it was not deemed necessary. The students signed agreements with the understanding that all information would be confidential, and numbers rather than names were assigned to each student. The students also agreed that the information could be used for further research and reporting (see Appendix 2). Participants were allowed to answer in either English or Spanish.

Materials

Three questions were chosen for language learning beliefs for this particular study:

Question 1: How would you describe your beliefs about learning a second language?

Question 2: Describe a previous event (positive or negative) that helped develop your beliefs about learning a language.

Question 3: Explain how the experience from question 2 affected your behavior as a language learner.

Procedure

This interpretative study used qualitative measures to determine students' beliefs and perceptions about language learning. Student statements were reviewed for completion and relevance according to each of the three questions. Then, the statements were labeled into either the economic or the sociocultural perspective per question. After that, the responses were divided into the sub factors within each aforementioned perspective, providing a comprehensive view of student beliefs and perspectives. Once all statements were categorized, shorter emerging ideas were identifiable within each of the factors and sub factors. Then, those shorter themes were reanalyzed, thus providing a compilation of Colombian student language learning beliefs and perceptions. The results section will discuss these findings in detail.

Results

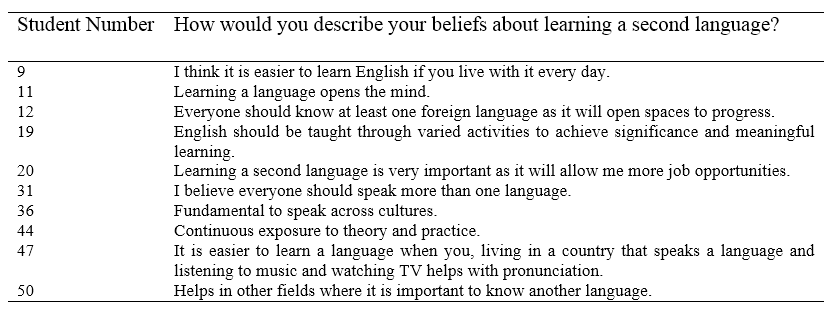

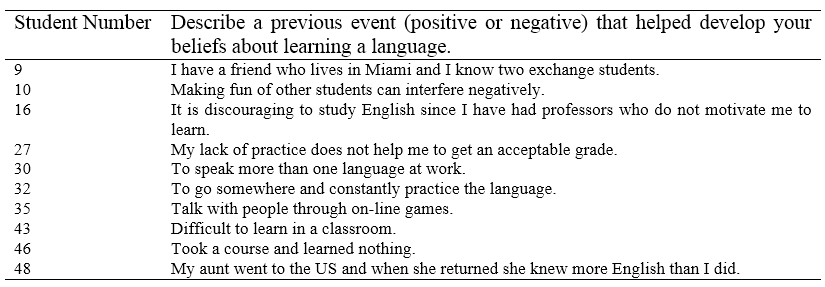

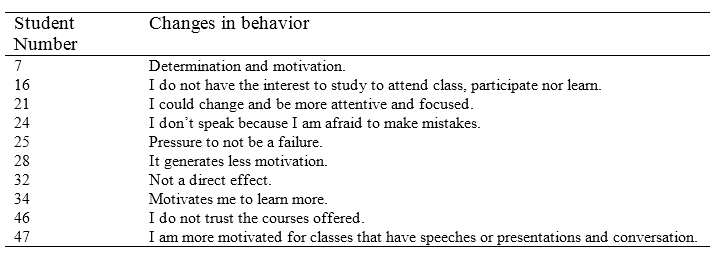

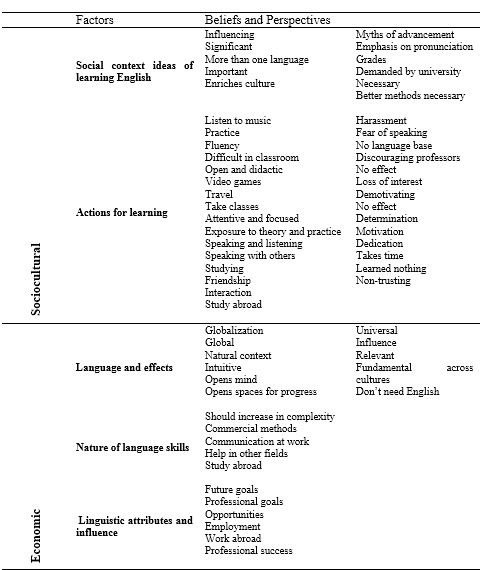

The fifty student participants divulged a range of beliefs and perceptions with regard to their language learning, their experiences, and the ways in which those experiences affected their behavior. The responses demonstrated honest and detailed statements, which made for a comprehensive analysis. Tables 1, 2, and 3 represent some of the relevant student answers. Table 4 shows the triangulation of the student comments within the sociocultural and economic factors and the sub factors of this study.

The statements in Table 1 demonstrate students' fundamental ideas that English is important to learn in order to communicate across cultures, that it is important to practice continuously, and that language learning provides opportunities for progress. These statements indicate a sociocultural shift toward more intercultural and economic interests and demonstrate the importance of continuous practice for fluency.

Student statements demonstrated more positive than negative experiences (see Table 2). However, it is important to recognize that students still have motivational and affective issues based on their classroom learning experiences and demotivating teachers. These results also demonstrate that English education's sociocultural aspects are shifting toward experiences that are more realistic rather than the "typical classroom." The results also point to the importance of speaking English for work purposes, which again demonstrates a focus on economic practices. All of these results thus demonstrate a need for changing teaching approaches.

Student-reported changes in behavior (see Table 3) also report positive and negative perceptions. Some students, for example, reported no change with regard to the experience, whereas others were motivated and wanted to learn more. It is important to note that some students reported that the classes in which included more interaction and student production the more motivating their experiences. Some students stated that there was a fear of failure. These concerns reveal a lack of both interest and motivation in learning the language.

Table 4 represents the compilation of the most common themes throughout the two major factors (economic and sociocultural) and their representative sub-factors. Beginning with the sociocultural perspective, and considering the social context and their ideas of learning English, it is apparent that their beliefs reach beyond necessity and compulsory language education and show that knowing other languages is becoming a cultural phenomenon, thus demonstrating students' willingness to learn a language. Regarding learners' actions that facilitate or hinder learning, we can see that there is still a fear of learning a language for various reasons, which from a teaching perspective could have indications for teacher classroom behaviors and practices. Given the expression of such fears, the fact that students want to practice and interact with others is both emergent and relevant.

The economic factors in Table 4 begin with language and its effect. Students' perceptions reveal some resistance as one student commented: "My parents don't speak English, so why should I have to learn it?" This demonstrates a tie to the mother tongue and possibly implies one or more key differences within the learning contexts of Colombia. The other comments revealed that English is a universal language and relevant and fundamental across cultures. The comments also indicated that language learning should be natural and intuitive.

Regarding the nature of language skills that could be developed, student commentary demonstrates that communication skills for particular purposes are a key reason to invest in learning English. Their comments also refer to the simplicity of English language learning and the vast array of commercial methods that are available. Looking at the final area, both dimensions equally, student statements strongly reveal the need for English to assist in professional success and other financial opportunities. These responses imply that students believe that learning the English language is not only a cultural fact, but also that such skills will influence their future socioeconomic position.

Discussion and conclusions

The results indicate that students strongly believe that language learning is social, fundamental and necessary to be successful not only in learning settings, but also professionally. Student concerns demonstrate that learning a language is more than a classroom activity, and that learning should be addressed in ways that are more meaningful. These ideas concur with beliefs about language learning studies. For example, the categories that belong to the BALLI (Horwitz, 1985) are still prevalent and useful for language learning and teaching today; the difference now is how to apply and provide students with learning experiences that go beyond traditional and classroom-based learning environments. Students want interaction and production, not only with their peers, but also with others in the world.

Borg (2011) noticed that beliefs could shift through time. Therefore, if teachers could motivate students with more reflective and thoughtful practices, perhaps the benefits would become balanced between economic and sociocultural ideas. That is to say, if we could change our learning environments into engaging and thoughtful arenas of equal participants, students would more likely adapt, and, as Ellis (2008) stated, remove the perceptual mismatches between learning a language to learn and learning a language to use and intensify the "journey" (Miller & Ginsberg, 1995).

With regard to sociocultural and economic perspectives of learning, the results revealed that knowing English as a second language is a cultural fact, and classrooms need to reflect this notion. Though there still exists resistance in learning the language, if teachers commit to encouraging language skills in meaningful and practical ways, students could change their perceptions of their investment and reap the benefits of professional success and other financial opportunities.

In conclusion, English language learners demonstrated the need to shift the current practices of language teaching. Providing positive experiences and meaningful learning and addressing the student more than the method will influence language learning. Possible shifts could include:

Interactive classroom teachers through reflective thought

Post-method ideas of particularity, practicality, and possibility (Kumaravadivelu, 2006)

Contextualizing learning materials and processes

Content and language integrated learning (CLIL) methods

Intercultural and interlanguage experiences

Some future research could include implementing interventions that address students' beliefs and perceptions, creating materials for post-method learners, or applying CLIL to primary or secondary schools based on contextual affordances and measuring its success.