Introduction

Research training has become a key component in language teacher education. Even though we are at seemingly opposite ends on the teaching spectrum-José Vicente as a teacher educator and Linda Katherine as a student teacher-the need to engage in such a form of training brought us together through a research incubator. In this pedagogical reflection, we describe our experience in research training, and then we articulate it with existing theory to reflect upon the role of research mentoring in language teachers’ professional development. This article is divided into three main sections. In the first one, we will contextualize the conditions for research training in teacher education programs in Colombia, in compliance with the latest government reform (materialized in Decree 2450 of 2015, Resolution 02041 of 2016, and Resolution 18583 of 2017). Then we describe research training in our institution, focusing on two choices students can make -the traditional path or the alternative one.2 In the second section, Linda describes her personal process of engaging in teacher research and connecting research-based knowledge with her teaching practicum. Here we adapt prior theory to produce a model of research competencies, attitudes, and aptitudes. In the last section, we explore the role of teacher research in language teachers’ professional development; analyze the dynamic role of research training within the school-university partnership; and discuss the nature, benefits, and limitations of mentoring for research training within the context of language teacher education.

Context

National context

The 2014-2018 National Development Plan(Law 1753 of 2015) aims to make Colombia “the most educated country in Latin America by 2025” (p. 83). In response to this ambitious goal, the Ministry of National Education (MEN) recently introduced a reform to teacher education programs that sets the conditions for obtaining the Register of Qualified Programs (hereafter RQP)3 and that equates them to those for the High-Quality Accreditation (hereafter HQA)4.

As stated in this reform, research constitutes a key component toward the achievement and maintenance of quality standards in teacher education. In fact, the Colombian government has identified research as the strategy that makes it viable for teaching programs “to develop a critical attitude and a creative ability in teachers and students with the mission of contributing to scientific knowledge, innovation, and social and cultural development” (Decree 2450 of 2015, p. 6). Therefore, by means of this reform, the national government has put forth specific demands for student teachers and teacher educators as regards research education.

As a starting point, and to ensure that student teachers receive effective research training, the government has established through Decree 2450 (2015) that teacher education programs are required to:

develop a culture of research in which students are to be trained in the spirit of inquiry, creativity, and innovation;

devise mechanisms to disseminate the program’s research and link it with the functions of teaching and outreach;

create research groups that contribute to the development of students’ technical and empirical knowledge in connection with teacher education, curriculum design, and the critical analysis of teaching practices; and

foster conditions for students to generate and explore research ideas through their participation in research-monitoring or research-incubator programs.

To supplement Decree 2450, Resolution 02041 (2016) and Resolution 18583 (2017) lay down the quality requirements that teacher education programs must meet in order to obtain, renew, or modify their RQP. The resolution establishes, among other conditions, that teacher educators should: (a) engage in research training and classroom research activities, and (b) produce and disseminate relevant knowledge derived from their research-related activities. In this way, the government wants to make sure that teacher educators will be able not only to participate actively in the academic discussion within their specific discipline, but also to prepare future teachers in keeping with the discipline’s developments.

Institutional context

With regard to the institutional context, the School of Education and Humanities at Universidad Católica Luis Amigó5 has graduated English teachers since 1996. From the outset, the program has had four plans of study with their corresponding RQPs. However, the current B. A. Ed. in English Language Teaching obtained its RQP in 2010 and started operating the following year. With over 900 students and over 30 faculty members, the program received HQA in August 2016.

According to the Program’s Educational Project (PEP)6, graduates should be able to apply pedagogical principles to teach English in the Colombian context and to conduct research projects to improve English teaching and learning in the educational institutions they work for.

In order to comply with the aforementioned requirements, administration and faculty have made research a key component of the English teaching program at Luis Amigó. Student teachers enrolled in the program can receive research training in two different yet complementary ways: On the one hand, all students must take the regular path of mandatory research coursework stipulated in the curriculum. As far as research training goes, this is the only preparation most students get. On the other hand, in addition to the mandatory courses, students who want to further their research education can undertake an additional path of research-oriented extracurricular activities, which involves joining an in-house research incubator or semillero7 and eventually becoming research monitors and/or research assistants.

Students who choose the regular path have to complete a series of research courses leading to the completion of their graduation paper. Starting in the fifth semester, this coursework is made up of three seminar courses administered by the Research Office8 and two graduation paper courses delivered only to students in the English teaching program.

Each seminar extends over a period of 16 weeks. The first seminar addresses the general methods and applications of research across different areas. The second and third seminars focus on the philosophical tenets and methodological approaches of the quantitative and qualitative traditions (Reichardt & Rallis, 1994), respectively.

Classes of up to 90 students from different undergraduate programs take these mandatory courses. A team of three tutors, who come from different programs and have different perspectives on research, is responsible for conducting the on-campus sessions, which are mostly theoretical and lecture-based. The tutors have limited time to interact with each other and with students, whether in class or outside of it. Furthermore, students have to take four computer-based exams spaced out throughout the course, but they rarely receive sufficient feedback on their test results. Under such classroom conditions, the relationships that teachers build with students are rather impersonal and the vision of research that students derive from their instruction is often fragmented.

After taking the research seminars, students from the English teaching program have to take two consecutive courses leading up to the completion of the graduation paper requirement. Faculty members teach both courses with English as the primary language of instruction. In the first one, students are required to present a research proposal designed in response to the educational needs they may have perceived within the context of their teaching practicum. In the second, students have to implement the proposed project under the guidance of their advisors and systematize it in the form of a research report.

For a large number of students, the graduation paper project constitutes their first hands-on research experience, yet they manage to produce findings that measure up to the standards set for their level of education. More importantly, after completing their research study, especially during the public defense of their projects, most of them manifest a deeper appreciation for the role of research in their professional development than they had at the beginning of the course. Unfortunately, this learning process becomes far more difficult than it should be for those who take only the regular path of mandatory courses, as many of them have often developed apprehension towards research by the time they have to face the graduation paper requirement.

On the other hand, the alternative path to get research training involves taking part in a semillero. For Torres Soler (2005), “Semilleros […] constitute a new model of teaching and learning. They are conceived as a space for the exercise of freedom, academic criticism, creativity, and innovation” (p. 2). According to González (2008), by forming these groups, institutions seek to foster a research culture among undergraduate students, who come together to conduct activities related to research training, formative research, and networking (p. 186). Echeverry (as cited in González, 2008) emphasizes that semilleros constitute a space for the integral development of their members, whereby they learn to design investigative tools and develop cognitive, social, and methodological abilities.

At Luis Amigó, the Research Office established that “semilleros are formed as a strategy for the integration of different areas of knowledge [by] groups of students, graduates, and teachers'' (Puerta & Macías, 2013, p. 6). Luis Amigó’s semilleros emerge from research groups or lines of research and depend upon them. Currently, Luis Amigó has 15 research groups and 46 lines of research, and only researchers who participate actively in the different research groups at each school can coordinate a semillero, which in turn must have at least four students to function.9

The English teaching program at Luis Amigó has one research line, Construcciones Investigativas en Lenguas Extranjeras (Research Constructions in Foreign Languages, or CILEX), belonging to the School of Education’s research group -Educación, Infancia y Lenguas Extranjeras (Education, Childhood, and Foreign Languages, or EILEX). CILEX, in turn, supports five semilleros. Students from the English teaching program who want to join them must complete one year of research training in the Semillero Sensibilización (Awareness Raising Research Incubator). In this initial group, student teachers become familiar with the role of research not only in educational contexts but also in their own professional development. Once students have completed this first stage, they are in a position to enroll in one of five thematic semilleros in the following areas of English language teaching: (1) language assessment and acquisition, (2) technology integration in the classroom, (3) linguistic policy and planning, (4) cultural studies, and (5) language teacher education.

Teacher-researchers in the program coordinate these five semilleros. Each of them comprises a group of six to fifteen students from Luis Amigó’s English teaching program. Students meet with their coordinator at least once a week for two-hour sessions; however, the length and frequency of the meetings vary greatly depending on each semillero’s commitments, so much so that some weeks coordinators spend up to eight hours with their pupils. Ordinarily, coordinators guide students through the design and implementation of research projects tied to their thematic line of interest. This training involves formative activities that cover the entire lifespan of a research project, from its inception to its dissemination at academic venues. Therefore, semillero coordinators also assist students in presenting at academic events and writing academic manuscripts.

José Abad has coordinated research incubators since 2010. First, he coordinated the incubator on language assessment and acquisition; as of 2016, he coordinates the one on language teacher education. Linda Katherine joined the semillero led by Professor Abad in 2012. In the following sections, we describe our personal experience in and our reflection upon research education thanks to our participation in this semillero and the impact it has had on our professional development, our teaching practices, and our relationship, which has developed around the dynamics of mentoring.

Research experience

Taking the first steps

According to McKay (2009), one of the main reasons teachers do research is to become more effective. She considers it “essential that novice teachers be introduced to the basics of classroom research methods and assumptions” (p. 281). In line with McKay’s statements, I, Linda, believe that engaging in research training activities not only enables novice teachers to be successful, but also provides them with a better understanding of classroom research itself.

I became involved in research in my first semester at the English teaching program. I started in Semillero Sensibilización, where I learned the three essential elements of research: “(1) a question, problem, or hypothesis, (2) data, (3) analysis and interpretation of data” (Nunan, 1992, p. 3). After this initiation, I joined the incubator on language assessment and acquisition in the second semester of my bachelor’s degree.

This semillero motivated me to keep learning about research, so I took part in my first research project, which dealt with factors and strategies affecting students’ preparation for English exams. This project brought along some valuable lessons. I learned to transcribe interviews and to codify qualitative data using specialized software. Furthermore, as McKay (2009) states, one of the challenges first-time researchers face is sharing “their research findings through presentations and publications” (p. 286), which I did for a poster presentation about codes and conventions for transcribing interviews. Finally, this project helped me realize that assessment and learning strategies are two important tools I want to include in my academic and professional life.

Engaging in research

After my first project, I had the opportunity to be a research assistant in a cross-institutional research project led by Professor Abad on learning-strategies instruction. The functions I performed in this project included:

Participating in the design of data collection instruments (rubrics, surveys, and questionnaires)

Managing databases of participants and test and survey results

Writing down team meeting minutes

Coding questionnaire responses

Using NVivo® software to help analyze qualitative data

Assisting in the creation of graphs for quantitative data

In this project, I worked with very knowledgeable researchers and other student teachers. As experienced by Castro-Garcés and Martínez-Granada (2016), who explored the benefits of collaborative action research, all the members of the research team learned from one another, even though the roles we played throughout the study were different, and precisely because of that. For example, I vividly remember my meetings with co-researchers and methodological advisors from whom I learned various ways to approach both the collection and analysis of data. Consequently, my knowledge regarding specific aspects of research improved significantly.

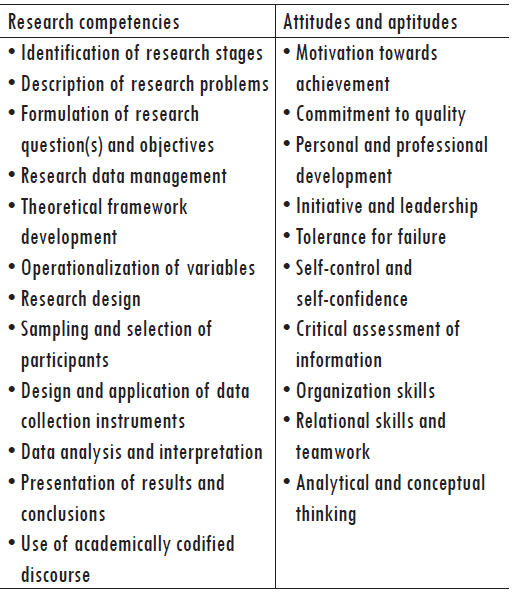

According to De Faría and De Alizo (2006), successful teacher-researchers should have a high level of technical and generic competence. Technical competencies are associated with the expertise and academic knowledge concerning the management of concepts, techniques, and procedures applied in the research process. On the other hand, generic competencies refer to personal and human qualities that include motivation, initiative, and relationships management (p. 161).

Based on our experience, we adapted De Faría & De Alizo’s theory (2006). For us, technical competencies refer to skills that develop over time because of the continual practice of research, whereas generic competencies are attitudes and aptitudes that researchers bring to research activity at any given time. Competencies are research-bound; in contrast, attitudes and aptitudes may improve as a result of doing research, but their development is neither restricted to nor contingent upon it. However, they are both necessary for the professional development of teacher-researchers. Because of the different functions I played as a research assistant, I have significantly developed my research competencies and strengthened my research attitudes and aptitudes. Table 1 shows a synthesized list of these competencies, attitudes, and aptitudes.

Incorporating research into the practicum

One of the most relevant aspects of an English teacher’s education is the practicum (Cohen, Hoz, and Kaplan, 2013). Gebhard (2009) states that, “A variety of terms is used to refer to the practicum, including practice teaching, field experience, apprenticeship, practical experience, and internship” (p. 250). Because of my background in research, I decided to incorporate research-based knowledge into my practicum. Consequently, I introduced language-learning strategies (Chamot & O’Malley, 1990; Cohen & Weaver, 2006; Oxford, 1990, 2011; Wenden & Rubin, 1991) to my 11th grade practicum class in order to prepare them for college life and help them enhance their performance in English oral assessments.

Abad and Alzate (2016) define learning strategies as “thoughts and actions purposely employed by learners to manage and self-direct their learning” (p. 132). I applied a diagnostic exam to assess students’ oral skills and an online questionnaire to explore their current use of learning strategies. During the preparation of this article, I implemented learning strategies instruction. As a follow-up, I plan to publish the results of my classroom research project.

In the following section, we will connect our research experience with prior theory to reflect upon the role of teacher research and research training in language teachers’ professional development, and we explore the notion of mentoring and the impact it can have on research education.

Discussion

Teacher research and teachers’ professional development

Research enhances language teachers’ professional development (Castro-Garcés & Martínez-Granada, 2016; Burns, 2011; Edwards & Burns, 2016). Teachers who take on research avoid the pitfall of professional stagnation because research takes them out of the comfort zone of unquestioned beliefs and routine teaching practices and prods them into active cycles of inquiry, data collection, reflection, and reinterpretation of their classroom realities. Research also leads teachers to reconfigure their relationships with students, parents, colleagues, and supervisors, thereby helping them to reframe their own teaching identities in light of their role as active agents of change within their own school communities. Moreover, the need to connect their own projects to prior research- and theory-based knowledge helps teachers keep abreast of developments in the language teaching profession and gives them the opportunity to join in the scientific discussion within their own discipline. As a result, doing research builds up teachers’ knowledge and raises their status as professional educators.

Formal research, however, entails the application of highly specialized scientific methods that are rooted in complex epistemological and ontological paradigms. For this reason, teachers, as other professionals, normally require specific training to learn what research is about and how to conduct it. Due to its complexity, research must be learned under the guidance of a trained researcher. Therefore, research training often occurs in the context of a university, a socially designated center for the sponsorship and implementation of research.

Consequently, research training in language teacher education usually takes place within the school-university partnership and strengthens it. Unlike other forms of research that come about within the confines of a laboratory, teacher research (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1993, 1999; Cross & Steadman, 1996; McKay, 2009; Shagoury & Power, 2012) as a social construction requires researchers to visit the classroom repeatedly to test and advance educational theory, very much in the way Linda did it during her practicum. Furthermore, inasmuch as it requires the school-university partnership to exist, teacher research also strengthens this tie as it helps bridge gaps between theory and practice and between the ideals of academia and the actual demands of school.

As part of their advocacy for the pedagogical use of critical dialogue, Freire and Macedo (1995) wrote:

We must not negate practice for the sake of theory. To do so would reduce theory to a pure verbalism and intellectualism. By the same token, to negate theory for the sake of practice…is to run the risk of losing oneself in the disconnectedness of practice. It is for this reason that I never advocate either a theoretic elitism or a practice ungrounded in theory, but the unity between theory and practice. (p. 379)

In line with their thoughts, we believe that the perspective of an educational researcher who is unaware of the realities of the classroom is as limited as the practice of a teacher who is not informed by theory, inquiry, and reflection. By making this statement we want to draw the line that connects not only the school with the university but also educational research with teacher practices in the classroom. At the heart of this argument, which also underpins current advocacy for research training in language teacher education, lies the notion of teacher research we mentioned before.

In the words of Cochran-Smith & Lytle (1999), teacher research refers to “all forms of practitioner enquiry that involve systematic, intentional, and self-critical inquiry about one’s work” (p. 22). For Shagoury & Power (2012), teacher research is “…research that is initiated and carried out by teachers in their classrooms and schools” (p. 2).

Lawrence Stenhouse (as cited in Elton-Chalcraft, Hansen, & Twiselton, 2008), proponent of the educational action research methodology, perhaps the most widely used in language teacher education programs in Colombia, was radical in his promotion of teacher research by stating that “[educational] research and development ought to belong to the teacher” (p. 12). Since then, teacher research has become not only a fundamental component of educational research but also a movement with clear political undertones that has garnered worldwide support from an important number of scholars in the field of language education (Allwright, 1993; Allwright & Bailey, 1991; Borg, 2006, 2013; Burns, 2010, 2011; Freeman, 1998; McKay, 2009; Nunan, 1992). But the call for teacher research in language teacher education does not come only from international experts in the field. The very reform we referred to in our introduction makes explicit appeals that teacher educators be engaged in classroom research.

From our perspective, it would be a huge contradiction to promote the call to educate language teachers in doing research and simultaneously maintain that educational research can be relevant without incorporating research that is conducted by teachers within the context of their own schools and classrooms. And even though not all educational research comes from teachers, we believe that its pertinence depends on the effectiveness with which it can hinge on and respond to the actual needs of students and teachers, whether in its inception, development, or outcomes.

In short, teacher research is the catalytic force that can help teachers reconcile educational theory and teaching practice. It is through inquiry, observation, dialogue, and reflection, methodically carried out in the form of research, that teachers can generate contextualized theory and bring a meaningful praxis to bear. In our experience, the potential of research to further teachers’ professional development, bridge theory and practice, and strengthen the school-university tie is maximized through mentoring.

Mentoring

By learning to do research together, we gradually entered a mentor-mentee relationship. Hence, I, José Vicente, felt a profound need to clarify what mentoring entails. According to Malderez (2009), mentoring is a “process of one-to-one, workplace-based, contingent and personally appropriate support for the person during their professional acclimatization (or integration), learning, growth, and development” (p. 260).

Malderez also suggests that successful mentoring occurs within educational environments that supply adequate conditions for mentors regarding time, remuneration, training, and support so that they can perform their role to the best of their ability. Consequently, as happens with teacher research in general, mentoring in language teacher education requires the link between the school and the university. Malderez is clear about this connection when she states, “in initial teacher preparation, mentoring often occurs within a partnership between a license-giving institution (university or college) and the school” (p. 261).

From this perspective, mentoring in language teacher education usually takes two of the following forms: a university academic that guides the educative process of a graduate or undergraduate student, or an experienced teacher that takes under his or her wing a novice teacher in a school context where they both work. In either case, mentors are experienced teachers. In the case of research mentoring (Borg, 2006), the knowledge about research that mentors hold almost invariably comes from their own educational background at the university level.

All the same, effective mentoring demands clarity as to the roles that mentor and mentee play with respect to the novice teacher’s preparation. In their earlier work, Malderez & Bodoczky (1999) defined the roles of mentors as:

Models that mentees can look up to as concerns what it means to be a teacher

Acculturators who facilitate mentees’ integration into a specific professional milieu

Supporters who accompany the mentee through the emotional ups and downs of their professionalization

Sponsors who strive to ensure inclusion of the mentee into the professional community and facilitate conditions and resources for optimal learning, and

Educators who scaffold the processes of becoming a teacher, of teaching, and of learning to teach.

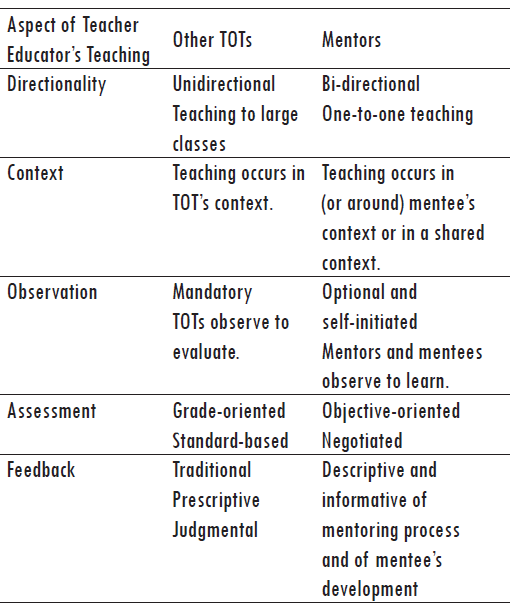

Malderez (2009) also points out that there are significant differences between other teachers of teachers (TOTs) and mentors. Table 2 summarizes some of those differences.

Table 2: Differences between other teachers of teachers and mentors

Note: Adapted from Malderez (2009)

Although there are variations as to the context and directionality of their teaching and the aims and means for observing and assessing students, the most significant differences between mentors and other TOTs lie at the core of the purpose with which they perform their roles. In this regard, other TOTs focus on the “maintenance of standards within an organization or system” (Malderez, 2009, p. 260), whereupon they often evaluate and train student teachers according to pre-set standards of expected behavior and thinking. These instructors often play supervisory roles that suppose controlling attitudes and prescriptive language. Hence, their students learn to play by the rules to fit within the model, but they have scant chances to pose questions, challenge standards, or build personal significance under their trainers’ supervision.

Mentors, on the other hand, focus on their mentees’ development and inclusion within a professional community, so they tend to go beyond the functions established by their job description. Teacher educators are hired to plan, instruct, oversee, coordinate, evaluate, and certify. But walking the extra mile for students to usher them into the profession the way mentors do requires a variegated set of skills and dispositions that educators deploy not because of the external demands or privileges inherent to their jobs, but because of a personal commitment to their students’ growth.

Mentors use feedback to guide mentees into noticing the rules and behaviors that best suit a particular school or professional community. Thus, mentors scaffold the development of mentees’ professional skills and help them link and validate various kinds of knowledge (Malderez, 2009). Mentees, therefore, are likely to become empowered self-discoverers who progressively engage in the twofold process of critically assessing their professional growth while deconstructing the impact of their practices on specific educational communities.

Mentoring in research training presents a number of benefits for mentors and mentees alike. In essence, research mentoring in teacher education implies learning to articulate teaching and research, which presents both mentors and mentees with the opportunity to develop core professional research and teaching competencies. These skills include noticing problems; asking key questions; collecting, analyzing, and interpreting relevant data; and using the ensuing results to adjust their own teaching.

Mentors can also help student teachers to bridge perceived gaps between theory and practice, one of the most problematic aspects of beginning a teaching career. When student teachers embark on doing research under the tutelage of a caring and competent mentor, they learn not only to interpret the realities of the classroom with the support of existing theories, but also to construct their own theories of effective teaching and learning by investigating classroom-specific problems. Hence, engaging in research helps student teachers develop their personal practical knowledge (Clandinin & Connelly, 1995; Golombek, 2009) in a more rigorous and conscious manner than if they did it via teaching only.

The development of such knowledge goes hand in hand with the acquisition of a professionally codified language (Malderez, 2009), which constitutes a fundamental step in joining the professional community of language teachers and researchers. As social creatures permeated by language, we learn to deal with existential problems when we develop the ability to name them properly, because it is only by naming our problems that we start to understand them. Thus, an additional benefit that educators can derive from participating in research is the progressive development of an academic discourse to consciously name and increasingly understand the complex interplay of factors that account for both teaching and learning.

Despite its many benefits, research mentoring also poses some significant challenges. To begin with, not all teacher educators are prepared either academically or emotionally to undertake mentoring. They may lack not only the educational background but also the willingness to move in that direction. In fact, because of their particular teaching style and the beliefs underlying it, some teacher educators may not want to develop a relationship with students as close as the one that mentoring requires.

Likewise, some student teachers may not have either the emotional disposition or the initiative to engage in the dynamics of mentoring. The research incubator program at Luis Amigó is a case in point. Although semilleros are an open-access extracurricular activity frequently publicized in the program, only 6% of the students follow this alternative cycle of research training. The other 94% take the traditional path of institutional research courses. As mentioned before, this decision leaves students with constrained research training in terms of the time they have to complete it and the rapport they get to build with their research instructors, which can naturally limit their understanding of what research entails, why they should couple it with teaching, and how to do so.

Students’ and teachers’ lack of interest, time, or knowledge to pursue research mentoring may not be the greatest challenge to implement it. With greater emphasis placed on research training in teacher education, an increasing number of students are starting to become interested in learning how to do research at earlier stages of their professional development. In our program, semilleros started in 2010 with only one teacher and one student. Seven years later, the six semilleros currently in operation gather almost 60 students overall. Teacher education programs, nonetheless, may be unprepared to satisfy their students’ need for qualified research mentors. With an ever-growing number of hats to wear in the areas of teaching, research, and educational management, teacher educators face an uphill climb engaging in research mentoring. Moreover, as the law has raised the bar in terms of the qualifications that teacher educators should have, programs will be hard-pressed to find the right faculty members to perform as mentors, and even more so to allot them sufficient time to conduct research mentoring responsibly.

Conclusion

In conclusion, engaging in research training through a research incubator program has changed the course of our professional development and our understanding of it. This alternative path to research education has reshaped our relationship and redefined our roles around research mentoring. We are convinced that teacher research plays a key role in the professional development of language teachers (Burns, 2011; Castro-Garcés & Martínez-Granada, 2016; Edwards & Burns, 2016), and that mentoring (Borg, 2006; Malderez, 2009; Malderez & Bodoczky, 1999) has the potential to maximize this experience for student teachers and teacher educators alike. In spite of its restrictions, research mentoring can help language teachers bridge the gap between theory and practice, firm up their teaching identities, and bolster their professional knowledge. Furthermore, research mentoring, which takes place within the school-university partnership, can contribute to its maintenance and enhancement. However, for research mentoring to work effectively, teacher education programs must make this form of research training a formal component of their curriculum so it can benefit all the students and teachers willing to embrace it.