The Colombian government, like many governments in the world, has a national bilingualism programme. Like the other programmes, the aim is to introduce a certain level of foreign language competence into the skill sets of students of all levels. The General Law of Education (Ley 115 de 1994) and the Law of Bilingualism (Ley 1651 de 2013) both require education in a foreign language at all levels of formal education. However, neither law actually stipulates that English be the mandatory language; this is more the result of moment-to-moment government policy than actual law. The choice of English, though, is, and has always been, related to economic activity and perceived international opportunities that accompany learning English (Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia, 2006). The Colombian government’s bilingualism programme has, over the course of its lifetime, attracted the ire of several sectors of Colombian society-criticisms that are usually to the effect that learning a second language affects the value of regional and national identities. In particular, it is compulsory English language learning that is argued to result in the wide scale devaluing of national and, particularly, regional identities given that English is such a ‘powerful language’, and its ties to powerful international cultures therefore represent a threat to local culture.

Negative popular perceptions have developed in many communities in response to the English language learning mandated by the national government that suggest it results in the depreciation of local and national culture and identity (e.g., the idea that learning English will make children ‘want to not be Colombian’). While it is true that such opinions may come more from political ideology or personal concern, others may arise from real experiences, and it is indeed accurate to say that the Colombian government has not presented any studies to actually support its decision to focus on English at the expense of any of the hundreds of other available foreign languages. A point in favour of these perceptions is the fact that there is a connection between language and identity, and there is much literature examining the relationship between the two, particularly the identities created by language learners in regard to their second languages. However, that is not to say that these perceptions are completely accurate as there is a lack of research regarding the change in perception and worth of L1 national and regional identities over time (or if it occurs at all). Hence, the purpose of this study is to detect changes (if any) in national and regional identity perceptions and to measure the perception and worth of national and regional identity in a small city in regional Colombia, thus analysing the strength of opinions regarding EFL and national identity.

Literature Review

The study of identity has blossomed over the last half-century. Until recently, identity was considered a fixed quality of a person-something that did not change and was with the person from birth to death (Joseph, 2004). This position, considered essentialist, shifted in the social sciences (including linguistics) into what is now known as post-essentialism or constructivism, which posits that identity is not an innate characteristic, but something which is constructed in social situations and interactions and that, as a result, can change over time. Importantly, the value given to an identity determines whether it will remain exercised by the individual and thus survive. The most influential of recent post-essentialist theories, the one most current theories are based on or in opposition to, has arguably been that of social identity theory. Proposed in 1967 by Henri Tajfel, this theory proposed a twofold view of identity: a personal identity composed of unchanging innate personal attributes (physical characteristics, etc.) and a social identity. This social identity consists of our group memberships and how they can conflict with each other. Given that we act differently in each of the groups of which we are members, it is possible for us to have many different social identities and change them over time. Ochs (1993) built upon the psychosocial view, stating that our social identities encompass all our reputations, roles, responsibilities, and interests-indeed, any point of reference that involves another person or group. Blackledge and Pavlenko (2001) furthered a similar position, arguing that an individual can never freely choose who they want to be, but must negotiate their identity positions in reference to overarching historic, economic, and sociopolitical structures, while Norton (2011) defined identity as the way a person understands their relationship to the world, the way that relationship is constructed across space and time, and how the person can understand possibilities for the future.

In terms of the relationship between language and identity, much work has been done over the last three decades. In line with the above notions of identity, Weedon (1987) identified language as the site of identity construction and noted that languages themselves are embedded within larger social structures, i.e., languages are not ‘clean’ mechanisms to be used for construction but bring with them all of the history and attitudes associated with them. Bourdieu (1991) continued in this vein of thought, arguing that language is a form of social ‘capital’. Language users and language learners choose language in a ‘linguistic market’ where languages have symbolic worth and power. Thus, language users and learners may choose from a ‘marketplace’ of languages according to their identity needs and desires, and the value of a language may be directly tied to its relationship with the speaker’s identity. Ochs (1996) posited that the relationship between language and identity is not direct but rather mediated by speakers. Successful speakers understand the socialized conventions inside language acts and create stances according to their understanding and mould identities according to how each interlocutor uses the linguistic resources available to them. Gumperz (1992) noted that language is used for contextualization, that is, speakers use linguistic signs to create the contextual space for situated interpretations based on shared meanings and values with Hall (2011) adding that all speakers belong to varied groups and that contextualization helps to take on group identities defined by group membership, which can be defined through discursive negotiation. Rajagopalan (2001) argued that language is used to ‘flag’ allegiance to one group or another and that a speaker’s choice of language is not a means of negotiation but a means of differentiating from other speakers, i.e., sociological othering or defining one’s identity in contrast to others and actively separating an outgroup as the ‘other’. Byram (2006) added that language or dialect choice is an effective means of creating belonging but also of othering other speakers. Lo and Reyes (2004) then built upon this notion by putting forward the idea that languages are used relationally, that is, to create identities in relation to other groups by actively othering and comparing groups to create identity positions.

National identity in current research and social thought has followed the path of social identity, meaning that it has been found to be enacted in relation to other identities. Anderson (1983) viewed nations as imagined communities, that is, groups which do not have a firm existence, but one in the minds of individuals expressed as a set of behaviours and attitudes. This is supported by Renan (1982) who saw the nation as a site of continuous construction by individuals forming groups, and national identity as neither a stable nor objective construct. Billig (1995) added that national identity is not fixed at birth but is an ongoing social construction performed and recreated through the invocation of recognised social activities and histories. Wodak, de Cillia, Reisigl, and Liebhart, (1999) argued that national identity has no essentialist substance but is the result of ongoing discursive construction between agents using publicly recognised discourse and socialization. Block (2007) added that even people born, raised and educated in a single region from a country nurture their sense of national identity through recognised symbols and activities.

Thus, a clear line of thinking exists: nation and nationality are not givens. A nation is something that must be constructed through discourse and public recognition, and nationality-the condition of belonging to said nation-must also be negotiated and as such is a social identity. The relationship between language and national identity can be understood in similar terms. With national identity argued as a social identity constructed through social meanings and history, it makes sense that language should be an important part of this construction-the choice of a language signals allegiance to a certain group and its history. Therefore, attitudes and language identities in favour of one language or another are signs of political allegiance and not of the inherent strengths of any given language (Rajagopalan, 2001; Byram, 2006), with language laws and policy reflecting choices favouring one history or another, and one group or another (Joseph, 2004).

In terms of language choice and identity, much research has taken place into the construction of second language identities and the effect of the L1 on second language identities. Norton and McKinney (2011) noted that identity offers foreign language learning theorists a comprehensive framework that integrates the learner with the social world and explains how social power relations affect learners and their access to the target language and its community. Recent research into language and second language acquisition has focused on the new identities that learners create with or in relation to the target language community (Block, 2007). Much of this research focuses on investment, linguistic capital, and minority identities in developing identities in the target language. While Block (2007) and Norton (2011) indicate that language learners create new identities based on the imagined community of the target language, we currently lack research on what effects foreign language learning (in this case EFL) has on the original national and regional identities held by the language learner in the country of the original national identity.

Investigation into original national identities until now has been undertaken in the case of learners studying abroad. Polanyi (1995), Twombly (1995), and Talburt and Stewart (1999) examined how the national language identity of students in study abroad situations is used as a means of combating uncomfortable foreign situations with the effect of increasing a positive view of the original national identity, while authors such as Acton and Walker de Felix (1986), Laubscher (1994), Bacon (1995), Wilkinson (1998), Pellegrino (2005), Kinginger and Whitworth (2005), and Isabelli-Garcia (2006) noted the same-that study abroad language programmes often have the opposite effect of what one might expect: ‘greater ethnocentrism’, i.e., the original national language identity is strengthened through exposure to foreign languages in a study abroad program. However, as noted above, studies on the effects of EFL on students in their own country in terms of their national identity are lacking, and given the different linguistic environments, previous conclusions may not be extendable to same-nation situations. Therefore, this investigation seeks to examine the effects that EFL learning has on the national and regional identities of people still living in their nation of origin.

Methodology

The purpose of this study was to see if any meaningful difference exists in the perception and value of regional and national identity as a result of foreign language learning in the country of origin of the language learner. As such, it was decided that doing so would require measuring the difference in attitudes and perceptions over time, if it occurred. This produced the need for measurable and comparable results, thereby requiring a quantitative method. However, in order to understand the reasons for any change it would be necessary to include a qualitative element. Thus, it was decided that a survey would be the most appropriate vehicle for the investigation, and to ensure a complete response rate, it would be distributed in person. Given budget restrictions, the number of surveys was limited to 400, producing a 4.9% margin of error at 95% confidence.

Survey Design

The survey was designed to begin with three initial demographic questions: gender, age and years of English classes taken. To measure the effect of foreign language education on identity perception and worth (in this case English language education) four categories were created in the years of English classes taken variable (0 years, 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years), thus measuring the effect of foreign language education over time. It is important to note that this is not a longitudinal study but rather cross-sectional; by using 400 surveys at 95% confidence, it can be supposed by sampling at the same place with the same independent variables of place of study (Universidad del Tolima) and city of origin (Ibagué) that the participants (with a variation of 4.9%) will be in a similar, and thus comparable, statistical situation. Therefore, while not longitudinal, the study should nonetheless give an indication of the effect of foreign language learning on perceptions and worth of identities without using the same participants over time.

The basic demographic questions were followed by 15 Likert items relating to the value of local and national identities, levels of belonging, and language worth. Finally, two yes/no/don’t know questions were given that directly asked about change in identity value, both of which were followed by open-ended ‘why?’ questions.

Survey Distribution

The survey was distributed at Universidad del Tolima in the city of Ibagué, Colombia. Ibagué has a population of 553,524 (Ibagué Cómo Vamos, 2016) and is the capital of the department of Tolima, in the centre of the country. Tolima has a population of 1.4 million people with its main industry being agriculture (rice and coffee) (DANE, 2005). Furthermore, Universidad del Tolima is the largest and most important public university in the region. It has a student population of approximately 20,000 that is characterised by belonging to either lower social classes in the capital of Ibagué or coming from small villages.

The survey was distributed in person on July 13, 2016, by the researcher and a group of 15 volunteers from his sociolinguistics class. The 400 surveys were divided into four groups of 100 to create quotas of 100 surveys for each level of exposure to English language instruction. The group then walked around the university selecting students at random asking for the level of English language instruction received. Students who had received English language education for periods of time exactly matching one of the four categories were invited to complete the survey. Students who agreed to participate were then given the required ethics and permission forms.

Data Analysis

Once all the forms were completed and the quotas met, the data from the surveys were entered in the statistical analysis programme SPSS v.22 by the researcher for analysis (omitting invalidated surveys). The demographic data were compiled into frequency tables while the Likert item results were divided by level of English exposure and tables of descriptive statistics were created for them. The arithmetic means were then tabled into a graph and received chi-squared tests to check for statistical significance. The final two quantitative questions were given the same treatment as the Likert items. The qualitative responses were compiled according to years of English language learning then analysed using content analysis to look for trends by grouping answers according to character.

Results and Analysis

Demographic Information

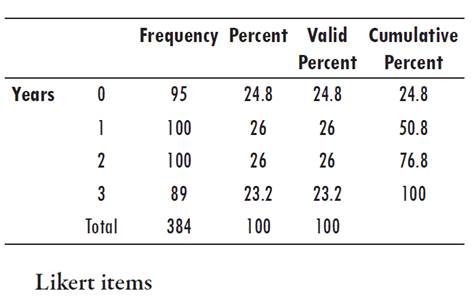

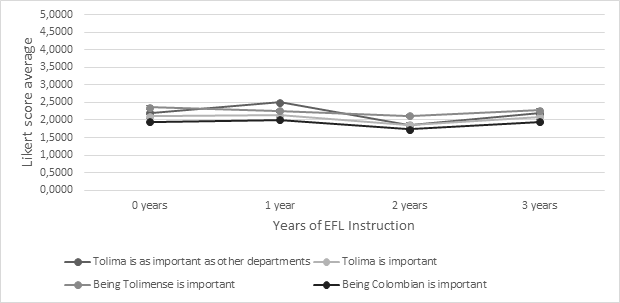

Of the 400 surveys given, 384 were valid (96%). Table 1 shows the valid surveys by years of English Education received (the principal variable). As can be seen in the table, the quantities of year-based sampling are roughly equal and unaffected by the 4% of invalidity. In terms of gender, there was a 9.4% difference favouring male respondents (54.4% male vs. 45.6% female), while ages ranged from 18 to 38 years old with a mean of 20.74 (σ = 2.82).

Likert items

The responses to question 4 (I am proud to be from Tolima) showed a positive trend within all years. The difference between year 0 (2.0211) and year 3 (2.0659) was a slight change of 0.0445 towards disagreeing with the statement. However, the extremely small size of the change (statistically insignificant) and the stable line of the graph (see Figure 1) show that EFL classes had no effect on regional pride. A similar result can be seen in national pride (question 5). The general trend was noticeably positive towards the statement ‘I am proud of being Colombian’ and, while there is a slight rise in the trend in the second year, it is stable. However, the difference between year 0 and year 3 was a 0.0384 move towards disagreeing with the statement (away from national pride) which is also not statistically significant enough to consider that EFL exposure caused a change in national pride.

Responses to the 6th question (I would prefer to live in another country), while not being as stable as the prior two items, showed much the same trend: in favour of the statement, and-with slight fluctuations-the overall result is minimal with a 0.0938 shift towards disfavouring the statement (statistically insignificant). This indicates that exposure to EFL classes does not affect the overall desire to live in another country. The trend seen in the 7th question (Colombia is a good country) is similar. It is noticeably positive towards the statement, and while there is fluctuation to both sides of the trend, the overall result is a 0.1134 movement towards disagreement. However, like the others, the result is statistically insignificant and unable to demonstrate that exposure to EFL classes changes perception of the country.

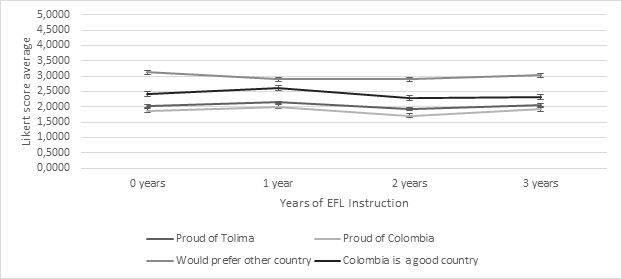

The 8th question (Colombia is among the best countries in the world) (see Figure 2) produced a slightly fluctuating trend over the four years. However, the trend starts and finishes ever so slightly in favour of the statement, with a 3-year change of 0.3064 in favour (year 0 average 2.7789, year 3 average 2.4725). Statistically significant, this item indicates that exposure to EFL instruction results in a slightly increased opinion of one’s own country. The following Likert item (I plan to stay in Colombia) follows a similar pattern, starting and finishing slightly in favour of the statement with a slight fluctuation in year 2. This item has a final change of 0.1141 in favour of the statement, a statistically insignificant movement which is too small to hint at larger trends.

The 10th question (I plan to stay in Tolima) produced a similar trend as well, although disfavouring the statement, beginning with an average of 3.1684 and finishing with an average of 3.0549. It produced a statistically insignificant difference of 0.1135 that, again, is too small to predict larger changes in attitudes. The final item in Figure 2 (question 11: Colombia is as important as Anglophone countries) differs from the other 3 items in that it shows a clear trend without fluctuation, producing a shift of 0.4502 in favour of the statement. This indicates that exposure to EFL instruction over time leads to a statistically significant, slightly more favourable view of Colombia when compared with Anglophone countries.

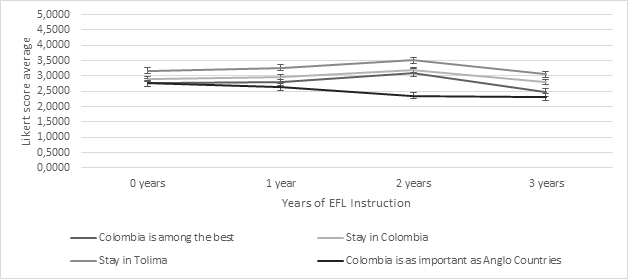

The next four Likert items (questions 12-15, see Figure 3 below) produced patterns that were very similar to each other: relatively flat lines in favour of the respective statements, all with statistically insignificant changes in value over time, thus indicating that EFL instruction has no effect on their agreement with the statements. The statements included the following: Tolima is as important as other departments (0.0127 change over 3 years), Tolima is important (0.0174 change over three years), Being Tolimense is important to me (0.0832 change over three years) and Being Colombian is important to me (0.0086 change over three years).

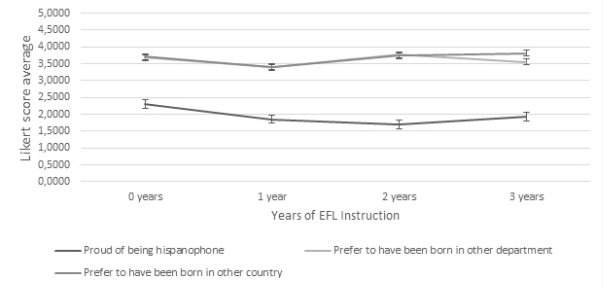

The responses to the final Likert items can be seen below in Figure 4. Question 16 (I am proud of being a Hispanophone) starts in favour of the statement, and over the course of three years of EFL instruction strengthens in favour by 0.3822 (statistically significant). This result lends itself to the inference that EFL instruction actually strengthens the identity of the native speaker instead of weakening it (albeit very little). The next two statements (I would prefer to have been born in another department and I would prefer to have been born in another country) show variation over the years but begin and finish against the statement with only minimal change: 0.0858 and 0.0974, respectively, statistically insignificant changes.

Yes-No Questions and Open Responses

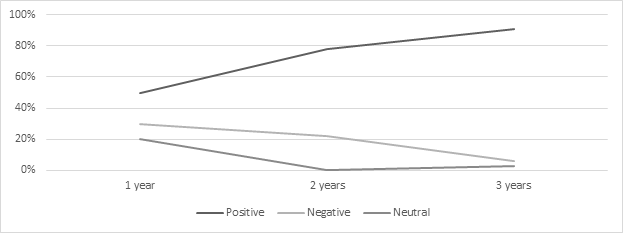

Questions 19 and 20 dealt with direct perceptions of change in identity value with responses of either yes, no or don’t know, followed by an open why/how question. The results were tabulated and graphed, and the open responses were classified as either stronger (Colombian or regional identity stronger), weaker (Colombian or regional identity weaker) or neutral (neither stronger nor weaker, or irrelevant). Question 19 (Do you believe that your opinion about being Colombian has changed since you started learning English?) produced a very clear trend which can be seen in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Responses to Question 19 (Do you believe that your opinion about being Colombian has changed since you started learning English?)

As can be seen in Figure 5, there is a clear trend over the 3-year period regarding changed attitudes towards Colombian nationality, with a 36.3% change in attitudes towards Colombian nationality. The classification of the responses regarding the possible change can be seen below in Figure 6.

As Figure 6 illustrates, there is a statistically significant change in both positive and negative attitudes over the course of 3 years’ exposure to EFL instruction. However, the data show a particularly dramatic trend towards positive image changes that, when calculated with the percentage of change from Figure 5, gives a 33.2508% increase in positive perception of Colombian national identity versus a 2.178% increase in negative perception. Thus, it can be inferred that EFL instruction increases the positive value of Colombian national identity over time.

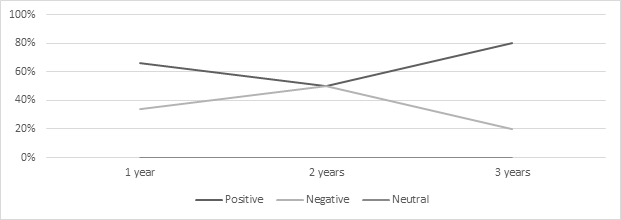

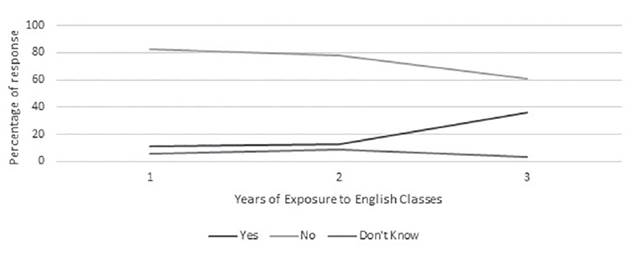

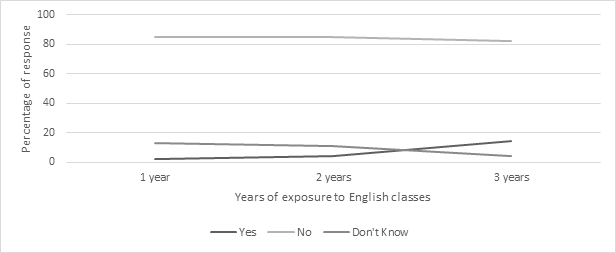

Question 20 (Do you believe that your opinion about being Tolimense has changed since you started learning English?) produced similar, though weaker, changes in responses. The percentage of yes-no-don’t know responses can be seen below in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Percentage of Yes-No-Don’t Know Responses to Question 20 (Do you believe that your opinion about being Tolimense has changed since you started learning English?)

As can be seen in the figure above, while most respondents did not evidence a change in value of their regional identity, by the third year 14% of respondents said that they had changed their opinion about their regional (Tolimense) identity, thus indicating a weak relationship between EFL and regional identity. Figure 8 below shows the classification of the open responses of the ‘yes’ respondents.

As Figure 8 shows, the change is exceedingly positive, finishing at 92% positive after the third year. When calculated with the 14% third-year change, the result is a 12.88% overall positive change in opinions about regional identity compared to a final 0.84% final negative change. We therefore can infer that exposure to EFL instruction over the course of three years provides a slight increase in the positive value of regional identity.

While the Likert questions related to perceptions about language learning demonstrated slight changes in positive identity (e.g., value when compared to other cultures, value of the identity itself), the participants disagreed with the clearly negative perceptions (preferring to have been born in another country or department). This disagreement increases over time of exposure to EFL instruction. In addition, a clear trend can be seen from the yes/no questions: English as a foreign language instruction does not negatively impact national or regional identities. Even though there is a slight change in negative perception (2.178% national, 0.84% regional), this pales in comparison to the positive change (33.2508% and 12.88% respectively, thus indicating that EFL instruction in Ibagué increases positive perceptions of national and regional identities.

Discussion

Within the spheres of identity and identity theory, this study provides a statistical foundation for several observations regarding EFL and identity. Concerns about changes in national and regional identity do not appear to be founded on anything solid, as this study not only managed to show that many such perceptions regarding EFL and identity depreciation are false, but also that the reality is often the opposite. Pride in country and region suffer no negative changes and in fact increase slightly, whereas positive opinions of the country increase significantly. Contrary to popular perception, instruction in English does not make students more likely to leave the country or even the department, and particularly strong opinions (such as preferring to have been born in another country) remain negatively regarded even after three years of EFL instruction, thus showing that EFL has no general negative effect on national/regional identity. Perceptions and criticisms of educational policy that propose EFL would diminish a student’s value of national and regional identity in themselves exemplify interesting observations about the nature of identity, in particular, overlapping points made by Bourdieu (1991), Tajfel (1978), Weedon (1987) and Rajagopalan (2001) about language and national identity, i.e., that identities are selected on a political basis. Proponents saying EFL prompts a change in identity value or causes identity loss characterize identity as a multifaceted creation under constant maintenance and construction, then posit that by choosing to invest in the social capital of the foreign language (Bourdieu, 1991), the students make a choice of political allegiance away from the original national language and towards the foreign language (Rajagopalan, 2001). They liken this to making a choice to depreciate the national language and the identity associated with it (and, ergo, the imagined community that comes with it). However, despite the logic behind the popular ideas about EFL and supposed identity change, the dynamic encountered is rather different.

Results from all national and regional variables in the Likert items never showed a lessening of value of Colombian or Tolimense identities in favour of foreign identities; they either remained flat or showed some degree of moving in favour of these local identities. Instead of favouring the social capital of the foreign language (and a powerful language at that), the students came to appreciate their own country more, with EFL instruction working as a contextual shared ground to reinforce Colombian cultural identity. The statistics provided by this study indicate that EFL instruction provides the context for students to appraise their habitus, and this contextual backdrop favours identification with the Colombian national group, even though the appraisal is being done in a language with a different set of social norms, group memberships and shared histories. This is demonstrated by increases in the Likert items Colombia is among the best countries in the world (question 8) and Colombia is as important as Anglophone countries (question 11)-the few that actually registered a statistically significant change-and by no increase in all other Likert items. The increase in the perceptions regarding Colombia as a country, its language and its place among other countries, along with the lack of any change in the statements indicating a negative position towards national identity indicate that EFL education provides the discursive space mentioned by Billig (1995) and Wodak et al. (1999). It appears that the EFL environment provides a space where the students, by invoking national symbols in linguistically contrasted surroundings, can compare their country and its symbols favourably to others, resulting in a more positive appraisal of their own nationality and creating a stronger link with their own national identity.

The results from the final two questions (Do you believe that your opinion about being Colombian/Tolimense has changed since you started learning English?) further support the last point and concur with the study abroad investigations performed by Polanyi (1995), Twombly (1995), and Talbert and Stuart (1999), who stated that foreign language environments tend to strengthen nation of origin national identities. However, in stark contrast to this research and the observations on study abroad education noted in Acton and Walker de Felix (1986), Laubscher (1994), Bacon (1995), Wilkinson (1998), Pellegrino (2005), Kinginger and Whitworth (2005), and Isabelli-Garcia (2006), EFL education in the country of origin does not increase the favour of national identity through greater ethnocentrism. No increase in pride was registered in any of the pertinent Likert items, e.g., questions 4 (I am proud to be from Tolima), 5 (I am proud to be from Colombia) and 15 (Being Colombian is important to me) which would be associated with ethnocentrism were an increase registered.

Thus, while EFL education provided in the country of origin strengthens the worth of national identity as study abroad foreign language learning does, it does not entail the nationality of origin being placed over another. This complex idea could be clearly seen in the results: there were positive shifts in how national and regional identities were appraised by 33.2508% and 12.88%, respectively, but not in categories equated with the importance of the national or regional identities as indicative of greater ethnocentricity or pride. Now, it must be taken into account that a common factor in the study abroad investigations was a series of negative feelings towards the foreign social environment in which the students found themselves, and this forced language to become a driving factor in not only stronger national identities but in developing ethnocentrism-a factor clearly absent in the present study as the students were in social environments native to them. This indicates that foreign language instruction in the country of origin would provide a more stable environment for the evaluation of national versus foreign identities and that this environment, contrary to popular belief, would actually increase the worth of the national identity but not ethnocentrism or nationalism.

The implications of the concurrence of these two aspects (increase in identity importance along with lack of ethnocentricity) are heightened when combined with the increase registered in the question I am proud to be a Hispanophone (question 16). Apart from an increase in local and national identities, the participants registered an increase in national language identity pride-the opposite of what popular conceptions suggest. The increase in pride in native language identity after EFL contact would suggest that the EFL environment provides the arguments that increase the social capital posited by Bourdieu (1991) against the capital of the foreign language. Whether or not this occurs through relational comparison of the languages as suggested by Lo and Reyes (2004) or through some use of the nationality building symbols and activities proposed by Block (2007) in the EFL classroom remains open to question and indicates a need for further research. However, this investigation has made it clear that in contrast to popular belief, EFL education does not diminish national or local identities but in fact increases them in addition to national language identity.

Conclusion

Quite to the contrary of common conceptions and beliefs, English as a foreign language instruction does not weaken Colombian national or regional identities. Instead, it may provide the contextual space for an appraisal of Colombian identities that results in a general move towards viewing these local identities in a positive light, being that after three years of classes EFL students showed greater appreciation of not only national and local identities but also the national language identity as well. Unlike research on study abroad, which also demonstrates the favouring of national identities, this study demonstrated that EFL instruction does not promote the ethnocentrism seen in study abroad investigations because there is no significant increase in national or regional pride. There is, however, an increase in positive opinions towards both national and regional identities, suggesting that learners appropriate the social capital of the target language to better gauge their own local identities and in the process appraise them more positively over time.

As an initial cross-sectional study, this investigation has shown that there is indeed change over time as a result of EFL instruction, but it also suffered the short-comings of cross-sectional studies in that it does not provide insight into the exact factors that caused the shift in attitudes in each of the different groups, factors that could be revealed through a longitudinal study performed over the course of several years with the same participants. However, the study does show that there is a general trend towards more positive appraisal of one’s own nationality after taking EFL classes (at least in Ibagué), and that regional identity also benefits from this type of education and opens the way to future (and perhaps qualitative) studies in the same field, particularly why national language identity increases and the what classroom factors may contribute to the changes in the appraisal of regional and national language identities.