Introduction: A Colombian EAP Program for PhD Students

To survive in the more-than-ever competitive academic world, non-English speaking scholars need to not only master the essentials of writing for publication in English but also develop effective public speaking skills (Zareva, 2009) to participate in the conferences organized by the academic communities of which they want to be recognized members. Research papers and conference presentations can pose challenges related not only to their content and elaboration, but also to their rhetorical and linguistic aspects. To help scholars overcome these challenges, more and more English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses for faculty or graduate students include research writing and public speaking skills as part of their language instruction. These courses are meant for graduate students to learn to master researcher genres (Hyland, 2009) such as the research paper and the conference presentation; however, being a graduate student does not necessarily guarantee knowing the basics of academic writing or public speaking in English. For this reason, graduate students in contexts in which English is not a first language need to start their academic English instruction with basic undergraduate student genres (Hyland, 2009) like the essay and the oral presentation.

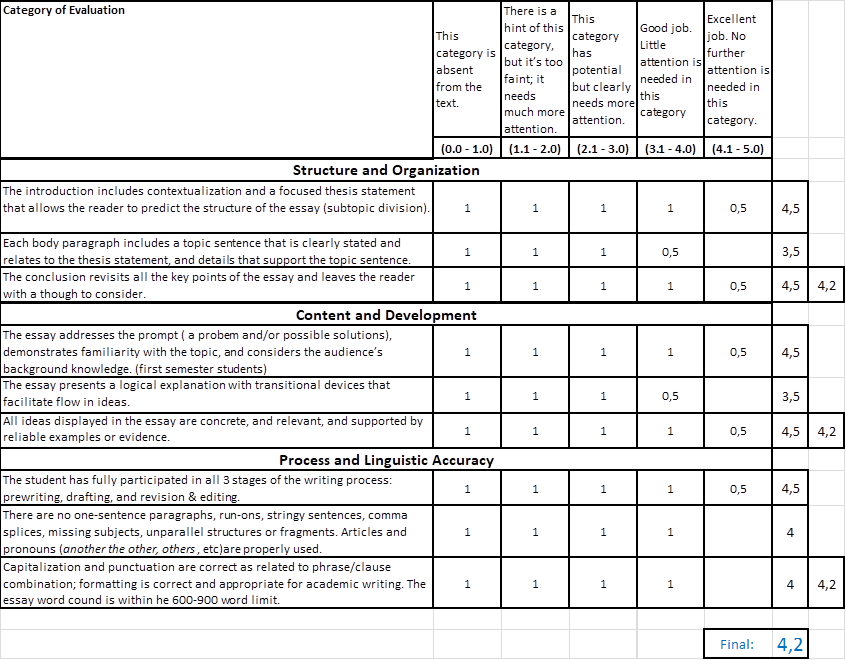

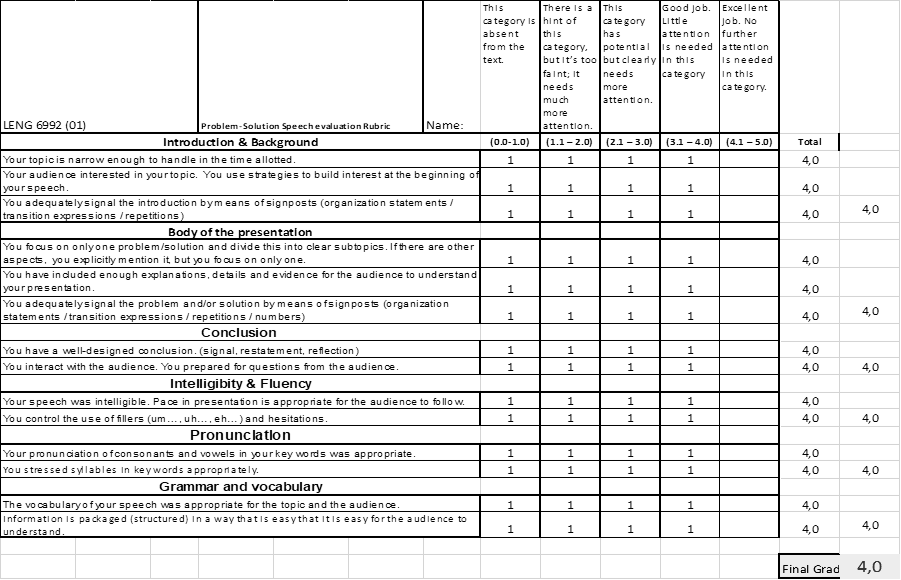

I am an instructor of the second course of an EAP program for different PhD programs at a private university in Colombia. In this course, my students learn to write academic essays and present them in the form of short oral presentations (OPs) whose content is their research in progress. I expect essays to be clear, organized, and linguistically accurate (see appendix A for criteria) and oral presentations (see appendix B) to additionally be engaging and easy to understand, given that the audience is composed of other PhD classmates from different disciplines. Essays usually meet the expected criteria, arguably because of the opportunity students have to revise and edit them with the help of the instructor. In the oral delivery, however, struggling students face several difficulties ranging from lack or misuse of linguistic resources to discontinuous, choppy, or halting talk; lack of engagement with the audience; and heavy dependence on slides or scripted versions of their talk, which in many cases recycle the sentences in the essays (Nausa, 2015).

This study1 analyses this last aspect: sentences (content) that students recycle from their essays either completely unaltered or modified. The purpose is to identify how the changes to the way in which written content was expressed to rework it in the oral mode are a mark of oral performance achievement. This article focuses on two mechanisms to express or modify written content in the oral mode: changes to the expression of modality and the inclusion of code glosses.

Research Questions

To approach this observed overall satisfactory achievement of writing objectives in contrast to the marked oral performance differences among students, this research aims to answer the following questions:

-. What are the differences between the essays and OPs in this class as observed in (1) the use of modality and code glosses with an emphasis on (2) the grammatical accuracy and (3) pragmatic appropriateness of the changed sentences?

-. What linguistic differences in the use of these two mechanisms are observed between high-rated and low-rated OPs?

Modality and Code Glosses

The effectiveness of an OP depends on aspects like focus on novelty, engagement with the audience, use of the visual channel, and simplification of information (Carter-Thomas & Rowley-Jolivet, 2003). Given that OPs are oftentimes based on written versions that might include complex linguistic structures such as nominalizations, heavily modified noun groups, and passive voice (Halliday & Matthiesen, 2004; Biber, Grieve, & Iberri-Shea, 2009), the adjustment of information might be a challenge for non-native speakers (NNS) or novice presenters. Failure to make appropriate discursive choices might place a processing burden on both the speaker and the audience. Two concepts-modality and code glosses, and their related mechanisms-allow us to understand the transformation of the way content is expressed in the transition from written to oral content by the same author. These two concepts have been widely studied within the systemic functional linguistics approach (modality) and metadiscourse (code glosses).

Modality

The study of modality has been approached under other related terminology: propositional attitudes (Cresswell, 1985), evaluation (Hunston, 1994; Swales, 2004), hedging (Hyland, 1996a; (1996b), and stance (Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad & Finegan, 1999), among others. Modality is defined as the judgement of what is being expressed (Halliday & Matthiesen, 2004). In you must finish the report soon, must indicates the speaker’s judgement towards the action expressed in the clause. Halliday and Matthiesen propose three related aspects in the understanding of modality: types, orientation, and value.

There are four types of modality: probability (may be), usuality (sometimes), obligation (must be), and inclination (want to or can). These four types can be grouped into two general categories: modalization (probability and usuality), or the degree of certainty or frequency of what is said; and modulation (obligation and inclination), degree of desirability or willingness.

Orientation refers to how modality is expressed according to two dimensions: subjective-objective (opinion-holder presence) or explicit-implicit (salience of expression of modality).

_________________________________________________________________________

(1) Eh, eh I think that the problems is this. The violence is more reported now. (GCOP)2 3

_________________________________________________________________________

In (1) I think that expresses probability in a subjective way; the opinion-holder is the person uttering or writing the clause (I). The same expression conveys modality in an explicit way; I think that is not inside the modalized clause the problem is this.

_________________________________________________________________________

(2) If we understand eh well this change in that conception we probably eh eh [fs] we be able to have a better cities and eh we [fs] and la… eh tss [fs] maybe we can eh preserve some important environments like the eastern mountains in Bogotá. (GCOP)

_________________________________________________________________________

In (2) probably and maybe express probability in an objective and implicit way; the speaker construes the proposition as objective since the adverbs do not directly refer to the pronoun we (the opinion-holder) but to the predicates (be able to have better cities / preserve environments). The adverbs also convey modality in both implicit and explicit ways: probably is inside the modalized clause ( we probably be able ) while maybe is outside ( maybe we can).

Value is the expression of modality between polarities: yes and no. For example, in obligation, polarities are expressed by the imperatives do and don’t, while intermediate values (modalities) can be expressed by modals such as should, or verbs such as required, which mark modality in values from strong (close to YES-do) to weak (close to NO-don’t).

Several previous studies have been carried out on English native speaker (NS) and NNS, novice and professional expression of modality in written academic genres (e.g., Barton, 1993; Hyland, 1996a; 1996b, 2005b; Lee, 2008; Aull & Lancaster, 2014; Bruce, 2016; Lancaster, 2016; etc.). However, no studies on changes in the use of modality to transition from written to oral discourse have been found. Two lines of study focus on English NS and NNS expression of modality in undergraduate and graduate programs.

First, modality in OPs has been studied in the context of L2 learners’ discourse socialization, the adaptation to a group’s discourse practices. Morita (2000) analysed the ways in which NS and NNS (Japanese and Chinese) graduate students expressed modality as epistemic stance. In a similar study on OPs as project work for L2 socialization, Kobayashi (2006) identified the use of relational and sensing verbs by undergraduate Japanese students as a mechanism to describe their thoughts and feelings from a Systemic Functional Linguistics approach.

A second line of study focuses on syntactic mechanisms used by NS and NNS to express stance in OPs. Zareva (2012) , for example, analysed the use of first-person pronoun stance structures, adverbials, and anticipatory it-stance structures (explicit-subjective) to persuade. In a similar study, Zareva (2013) analysed first-person pronouns to identify the identity roles construed by TESOL graduate students in their OPs, based on Tang and John’s (1999) typology of academic identities. Some of the roles found can be related to specific modality types. For example, the role of originator (e.g. I found that) can be interpreted as a strong, subjective, explicit way of expressing probability.

Like Zareva’s (2012), this pilot study seeks to identify how modality is expressed in graduate students OPs in English. However, this study puts more emphasis on the language choices to transition from written modalized content in essays to express it in OPs.

Code Glosses: A Definition and a Taxonomy

Code glosses have been studied within the concept of metadiscourse as the ways text producers organize their texts and interact with their audience (Hyland, 2005a). Vande Kopple (1985) proposes a classification system of metadiscourse: textual and interpersonal. Textual metadiscourse includes (1) text connectives (first, second), (2) code glosses (for example), (3) validity markers (discussed here as probability modality), and (4) acknowledgement of authorship (according to). Interpersonal metadiscourse encompasses (1) illocution markers (in conclusion), (2) attitude markers (discussed here as obligation and inclination modalities), and (3) commentaries (to directly address the audience).

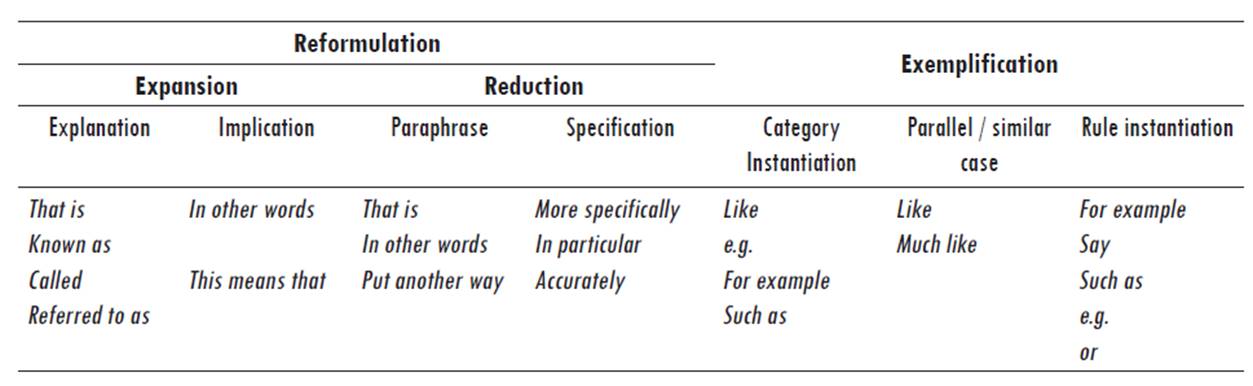

Although Vande Kopple assigns code glosses a textual function, it could be argued, as Hyland (2005a, 2007) does, that these devices also perform an interactional clarifying function. Hyland (2007) defines code glosses as actions that the writer or speaker performs to elaborate their discourse to make it clear and accessible to their audience, or as “small acts of propositional embellishment” (p. 267). Hyland classifies glosses into two general categories: reformulation and exemplification (see Table 1 for his taxonomy of code glosses).

Reformulation

In reformulation a new unit is introduced as a restatement of the old unit to frame it from a different stance, elaborate on it, or add emphasis to it. Reformulations are classified into two types: expansions and reductions Hyland (2007).

Expansions amplify the meaning of what was previously expressed and are concretized in two subtypes. One is explanations used to elaborate on the meaning of what was expressed by adding a gloss or a definition. Markers to introduce explanations are that is, known as, called and referred to as.

_________________________________________________________________________

(3) First eh, the (lineal synthesis) is called4 too eh [synthesis by steps]. This means, eh that eh [you can use one chemical reaction A eh plus B eh produce C.] (GCOP)

_________________________________________________________________________

Example (3) also exemplifies the other subtype of expansion: implication. Implications provide a summary or a conclusion of what was previously expressed and are typically marked by in other words and this means that.

The second type of reformulation is reductions. Reductions narrow down the scope of a previously expressed proposition.

One kind of reduction is paraphrasing, which offers a gist or a summary of what was previously expressed. Paraphrase markers include that is, in other words, and put another way.

_________________________________________________________________________

(4) In this model the labour market have a complete information and eh make the decision the [fs] about the salary or wages. (In this case, the labour market [fs] the labour market pay in order to eh individual productivity.) In other words, [more productivity implies eh more salary or wages.] (E1-P1)

_ ______________________________________________________________________

The other kind of reduction is specification. Specifications add details that constrain propositional interpretation. Some markers of specification are specifically and in particular.

_________________________________________________________________________

(5) First, general policies, these type of policies are supporting any kind of entrepreneurial acti [fs] activities, no matter what kind of firm there are making. And localized policy, specifically supporting high growth firms. (E1-P1)

_________________________________________________________________________

It needs to be born in mind that some signals, like in other words, announce that a code gloss will be used, but do not specifically announce whether the gloss will be an expansion or reduction. It is in the interpretation of the gloss that the hearer-reader identifies it as one or the other.

Exemplification

The second category of glosses is exemplification. Examples provide more accessible ways to interpret content. Hyland (2007) proposes three types of examples: category instantiation, parallel case, and rule instantiation.

The first presents instances of a general category; like and such as are markers of this type.

_________________________________________________________________________

(6) Overcrowding and poor sanitation expose individual [fs] individuals, especially children to the involvement of (parasites) such as [the malaria parasite plasmodium] transmitted by the female Anopheles mosquito. (GCOP)

_________________________________________________________________________

The second introduces parallel or similar cases to the one that needs elaboration; like is a typical parallel case marker.

_________________________________________________________________________

(7) Eh there is popular metaphor in the medical institution that says that your (body) is like [a building blocks], is formed by building blocks,language le building blocks like molecules. (GCOP)

_________________________________________________________________________

The third type provides a precept or instantiation of a rule; say, for example, and or introduce this type of exemplification.

______________________________________________________________________

(8) also (the emotion last a certain period and finally, may have a define location in the body). For example, [disgust is located in the stomach, eh or fear is located in the heart rate,] ok? (GCOP)

_________________________________________________________________________

Table 1 summarizes the code glosses taxonomy and includes some examples of their typical markers:

Research on code glosses in English academic discourse is framed within the study of metadiscourse and has mainly focused on written academic texts (cf., Valero-Garcés, 1996; Hyland, 1998; Bunton, 1999; Vergaro, 2004; Bondi, 2005; Murillo Ornat, 2006a, 2006b, 2012, 2016; Del Saz-Rubio, 2011; Li & Wharton, 2012; Basturkmen & Von Randow, 2014).

The use of code glosses has also been studied in academic posters, a written genre closely related to OPs. D’Angelo (2010, 2011) analysed the use of metadiscourse (including code glosses) and other visual elements as communication strategies in academic posters written by native speakers of English in different disciplines. In relation to code glosses, she found that similar interactional strategies across disciplines suggest cross-disciplinary conventions. Talebinejad and Ghadyani (2012) compared the use of code glosses in posters written in English by Iranians and native speakers of English. The authors found that NS use more code glosses, but fewer pictures in their posters, which was interpreted as NS’ perception of the process of persuasion as of high importance in the construction of arguments and the avoidance of ambiguous interpretations.

In oral academic discourses, code glosses have been studied mainly in instructor discourses for lecture comprehension by language learners (Aguilar & Arnó, 2002; Aguilar, 2008 ) and for their role and use in EAP classrooms (Bamford, 2005; Bu, 2014; Lee & Subtirelu, 2015).

Code glosses in spoken EFL student academic discourses, and more specifically OPs, have only appeared in a couple of studies. Kong and Xin (2009) analysed metadiscourse in Chinese non-English major EFL learners in basic oral communication tasks, including short non-academic OPs under testing conditions. The results of this study focus on the quality of spoken production as evidenced by the amount and type of metadiscourse (including code glosses) used. Alessi (2005) studied the frequency, form, and function of metadiscourse markers in OPs by advanced Italian learners of English. Although the presentations given by the students in that study were based on written content, no comparisons were made between the way information was conveyed in written sources and how it was translated into their OPs. The use of code glosses was analysed “to interpret and disambiguate meanings of words and phrases” (Alessi, 2005, p.184), but they were found to be almost entirely absent from the OPs as compared to NS oral discourses.

Analysis of the literature found justifies the study of modality and code glosses in OPs. The use of these linguistic aspects has not been studied to explain the transition from written to oral modes in contexts like the one described here.

Methods: Context, Participants, and Data Collection

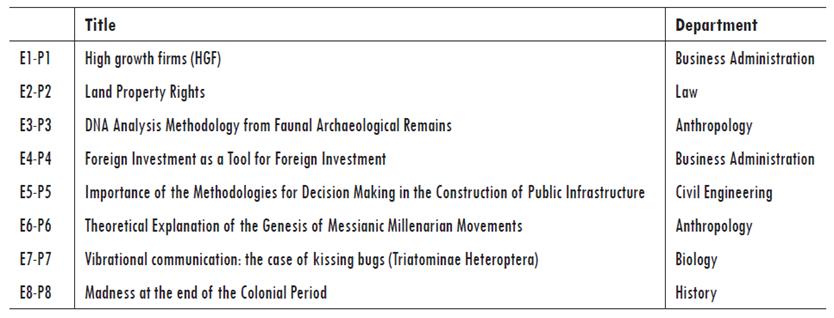

This research was carried out in a Colombian EAP program aimed at helping students enrolled in PhD programs in a private university in Bogotá improve their academic writing and public speaking skills (Janssen, Ángel, & Nausa, 2011). In the second course of this program, students learn to write essays and present them to their audience of multi-departmental classmates in the form of a short OP. The eight participants in this study were chosen from the nine courses taught since the first semester of 2011. Three students were enrolled in humanities PhD programs (anthropology and history), three in social science programs (law and business), and two in science/engineering programs (engineering and biology). Rough estimations allow us to state that students in this course would be placed between the A2 and B1 levels of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR).

The selection of students for this pilot study was based on the grades assigned to their oral presentations (see Appendix 2), on a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 being the maximum possible grade. Grades ranging from 3.9 to 5 were classified as high-achieving, those below the class average (3.8) as low-achieving. To obtain a balanced comparison, four low-rated and four high-rated OPs were chosen. A low-achieving grade did not necessarily mean a failing grade.

To identify the mechanisms used to present essay content in oral presentations, I compiled a corpus of eight pairs of parallel texts (11,064 tokens) following the Carter-Thomas and Rowley-Jolivet (2001) methodology of comparing parallel written (conference proceedings) and spoken (conference presentations) texts by the same author. In this study, all the texts were part of a class project in which students had to write essays (see Appendix 1) about the problems they were approaching with their PhD research. The essays were written based on the logical division of ideas (expository) structure (Oshima & Hogue, 2006). Essays had to be presented to the class in the form of a short OP. To prepare for the OP, students studied models of problem-solution speeches (Reinhart, 2005). OPs had to be 5 to 10 minutes long, include visuals like slides from presentation programs, be delivered keeping the class’ multi-departmental, non-expert, PhD student audience in mind, and include a space for questions and answers.

The essay and related OP subcorpora (see Appendix 3) contained 5,255 and 5,809 tokens, respectively. Essays were collected in the rough draft stage (without the instructor’s comments and suggestions) to guarantee that the samples reflected the students’ actual English use. OPs were videotaped and transcribed orthographically, including tags (see Appendix 4 for conventions) to mark reading from slides or script moments and speaking disfluencies.

Once the corpus was compiled, I read and colour-coded all eight pairs of texts to identify sentences expressing the same content in the author’s essay and OP transcription. 108 sentences (3,166 tokens) were extracted for analysis and compared to identify how written content was reworked in the oral context and the relative success of those mechanisms. Changes to aspects of modality were identified based on the SFL (Halliday & Matthiesen, 2004) account of the phenomenon (refer to Section on Methods). Markers of explicitness and subjectivity like modal verbs (must), adverbs of certainty (maybe) or clausal constructions (I think that...) were considered in the manual analyses. Code gloss analysis was based on the identification of elements not present in the essay but in the OP, which was interpreted as modifications made for the audience. Hyland’s (2007) code gloss marker taxonomy was useful in the identification of these elements.

Findings

This article describes changes to the expression of modality and inclusion of code glosses as ways to present originally written content in OPs and to generally distinguish high and low levels of performance.

Changes to the Expression of Modality

Among the three aspects in the expression of modality, change of orientation or value, and transition between types of modality were found to be two sub-mechanisms that students used to change written (w) into spoken (s) content as illustrated in (1w) and (1s)5:

_________________________________________________________________________

(1w) Some people have thought that this right is unlimited and that it is possible for the owner to do everything there.

(1s) Some people thinks that the property rights eh has eh essentially a individual conceptual reflects a individual conception, so they think they can do over their property eh anything that they want. (E2-P2)

_________________________________________________________________________

In (1w), two types of modality are expressed: probability and inclination. Probability is expressed objectively and explicitly (orientation) by some people have thought. Inclination is expressed objectively and explicitly by it is possible. To transform this content into the oral mode, the student kept the objective-explicit expression of probability (they think), but made use of subjective-implicit realizations of inclination such as ability/potentiality (can).

Syntactic choices made by the student in (1s) were both pragmatically and grammatically appropriate. First, the use of extraposed clauses (it is possible…) to mark stance has been found to be most frequent in the written mode (Carter-Thomas & Rowley Jolivet, 2001), and the use of modals (can) to express modality is typical of oral modes (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004). Additionally, the choices in (1s) fixed the meaning of what was expressed in (1w). (1w) fails to express the potential violation of the law (obligation) because it is written as expressing potentiality. (1s) clarifies the intended meaning.

The discrepancies in meaning between (1w) and (1s) can be explained as follows. Can and it is possible are two ways of expressing inclination, but can is also used to express obligation at a low value. Inclination includes two variants: potentiality and ability. The meaning in (1w) is clearly more inclined towards potentiality (not to low-value obligation) as confirmed by the surrounding lexical context (the right is unlimited, …do everything there). The meaning in (1s), on the other hand, places more emphasis on obligation at a low value, also as reinforced by the lexical context (reflects a individual conception, anything that they want).

From this analysis, it can be concluded that this student exhibited grammatical and pragmatic knowledge to transfer modalized propositions to the oral mode notwithstanding the inaccuracy in (1w). Grammatically speaking, he showed evidence of knowing the aspects (orientation and value) he could modify to express inclination. Pragmatically, he demonstrated he was able to select forms typical of oral and written academic discourses. As a result, his ability to modify the expression of modality could be conceived of as a marker of successful oral performance.

Low-achiever sentences in the OP subcorpus, on the other hand, did not exhibit the application of any of the abovementioned strategies. As can be observed in the following examples, modalized sentences are barely changed:

_________________________________________________________________________

(2w) In many archaeological context can be found remains of several types;

(2s) Eh [reading4] in [fs] in many contexts [fs] in many archaeological contexts, the archaeologists can found remains of several types. (E3-P3)

_________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________

(3w) However, in reality a movement can never be explained only by a cause. (3s) Ok the conclusion, eh [reading] in reality a movement can never be explained only by a cause. (E6-P6)

________________________________________________________________________

This lack of change in the oral version can be explained based on what authors like Zareva (2009) and Rowley-Jolivet and Carter-Thomas (2005) have found in their studies contrasting the performance of NS and NNS in presentations based on written texts: NNS tend to use language resources that are more typical of the written mode, which probably reflects their perception of OPs as more formal events, while NSs’ choices reflect a more casual and interactive perception of OPs. These authors, however, do not discard lack of grammatical and pragmatic knowledge as a potential reason for the NNSs’ choices, which seems to also be the case in low-rated OPs. Similarly, Flowerdew (2000) found that learner’s discourse in writing does not exhibit a high degree of modalization. In this study, low-rated OPs did not exhibit a high degree of modalization or mechanisms to vary its expression either.

Another way of modifying the written expression of modality was the transition between types of modality. The following examples illustrate this transition.

_________________________________________________________________________

(4w) As an example, in construction projects, people usually try to get quality projects, cheap, and in a short time.

(4s) We cannot obtain a cheap project in a short time and with high eh [fs] with high quality. (E5-P5)

________________________________________________________________________________

(4w) modalizes the process as usuality (usually). In (4s), this process is expressed as potentiality (cannot). (4w) construes the process as ‘a usual attempt’ while (4s) construes it as something that is not feasible. The surrounding lexical context along with the expression of modality construes the nuances of meaning. In (4w) failure to get the quality projects done is expressed with the verb try, which presupposes that something was attempted but not done; in (4s), this is expressed with the negative modal cannot.

This transition is effective despite a few word choice and grammar inaccuracies being evidenced. The student managed to keep the meaning of the original proposition and used proper syntactic devices for the types of modality he selected for the essay and OP.

The low achievers’ sentences, on the other hand, did not exhibit the application of any of the strategies discussed so far. Sentences (5w) and (5s) serve as an example to illustrate this situation:

_________________________________________________________________________

(5w) The DNA is a type of organic biomolecule found in the cells of all living organism and can even be preserved after the death of these (animals, plants or humans) for hundreds and thousands of years.

(5s) The DNA is a type of organic biomolecule found in [fs] on living cells and [fs] and can be preserved after the death of an organism: animals, plants, or humans for hundreds and thousands of years. (E3-P3)

_______________________________________________________________________________

Sentence (5w) is modalized as potentiality can and expressed in passive voice. However, (5s) shows no modification to the expression of modality or the use of passive voice. In fact, the sentence remains almost completely unmodified. Like the transition examples in (2w-2s) and (3w-3s), the observed lack of change in the oral version (5s) seems to reflect the tendency observed by Zareva (2009) and Rowley-Jolivet and Carther-Thomas (2005) in NNS presenters: low-achievers seem to resort to what they know (written ways of expression) and ignore other language resources that could make their OPs more casual and interactive.

Use of modalization and changes to its expression seem to be key markers to discriminate between levels of oral performance. As shown in the sample sentences, high achievers demonstrated their ability to modify the orientation, value, or types of modalities. Low achievers, in contrast, did not demonstrate such ability.

Use of Code Glosses

OP sentences expressing originally written content by the same author exhibit more than one type of gloss introducing content not originally expressed in essays. Sometimes gloss markers assign a new discursive role to content expressed in writing. Sentences (6w) and (6s) illustrate the use of two glosses: implication and rule instantiation.

_________________________________________________________________________

(6w) In the first case, if vibrations travel through substrate the legs becomes the first receptor. (6s) (They uses eh four (xxx) organs that are located in the legs, in (xxx) legs.) That means [that the [fs] they are feeling the vibrations that cames through the substrate] because [those vibrations come to first in contact to the legs.] (E7-P7)

________________________________________________________________________

Although (6w) and (6s) express the same meaning, and both are used as elaborations of previous content, they perform different functions in the essay and OP. In the essay, (6w) is used as an instantiation of one of two cases of insect organ receptors: legs and antennae, as evidenced by in the first case. However, this instantiation function is not carried out as a code gloss given that (6w) is not an expansion of an adjacent sentence; it is positioned as a topic sentence in a new paragraph. (6s), on the other hand, includes two examples of code glosses. The first (implication) is introduced by that means. The second case (expansion) is marked by because… to introduce and explain the result of the legs’ organ receptors being in contact with the substrate, implicit in (6w). Probably, the need to make this information explicit is the student’s perception that the technical term (substrate) might pose difficulties for the audience. Although because has not been categorized as a gloss marker in the metadiscourse literature (e.g. Hyland, 2005a; 2007), but as a transition marker, it can nonetheless be argued that it performs this interpersonal function when used to expand given content, as in (6s).

Cases of code glosses were also found in low-rated OPs; however, in comparison to high-rated OPs, their use lacked either grammatical accuracy or pragmatic appropriateness, as seen in 7w and 7s.

_________________________________________________________________________

(7w) Finally, the social ideas and treatments of madness have the component of the familiar care, derived of catholic precepts of charity, poverty, and mercy. Furthermore in colonial context, they are determined by gender, castes and professions,

(7s) eh finally the social ideas about eh the treatment and the comprehension of madness that are related with familiar care in (Latin American context) is different, totally different with the treatment eh of madness in eh [English countries] of eh [English colonies,] sorry, and eh [French colonies]. Eh but also is related about the gender, the castes, and the types of madness. (E8-P8)

_________________________________________________________________________

(7s) shows the use of specification. English colonies and French colonies specify the colonial context referred to in (7w). However, two drawbacks are found in the transition from the essay to the OP. One, the glosses are not introduced by a marker like like or such as. It is not only the use of the gloss that helps to specify the meaning, but also the use of a marker that clarifies the type of reformulation that is being made. Two, the content is altered in ways that do not seem to be pragmatically motivated. For example, in (7w) the idea that is conveyed is that social ideas about madness in colonial contexts…are determined by gender, castes, and professions, while in (7s) the lack of a subject in the last clause (…also is related…) obscures this meaning because it is not clear to what this predicate refers.

The identified cases of code gloss use in high- and low-rated OPs allow us to draw two conclusions. First, it can be claimed that both high- and low-achievers in this study understand when potential moments of confusion or need for elaboration arise. Therefore, their use of glosses can be said to be pragmatically relevant. Second, as in modalization of content, there is variation between high- and low-rated OPs in terms of grammatical accuracy and pragmatic relevance. The high achievers’ glosses were pragmatically correct, were introduced by standard markers (that is), and contained fewer grammatical errors. The use of glosses was not found in several instances when they were expected during low-rated presentations, notwithstanding its apparent ease of application and the assumed ample knowledge that this PhD population had about their own research topics.

Conclusion

In this article, I have tried to answer the following questions:

- What are the differences between the essays and OPs in this class as observed in (1) the use of modality and code glosses with an emphasis on (2) the grammatical accuracy and (3) pragmatic appropriateness of the changed sentences?

- What linguistic differences in the use of these two mechanisms are observed between high-rated and low-rated OPs?

I have described changes to the expression of modality and inclusion of code glosses as two mechanisms to express written content in OPs. These mechanisms have been observed as more consistently followed by high-achievers both in pragmatic (clarifying potentially confusing information, not altering original meanings) and grammatical (using more standard forms or with fewer infelicities) terms. These mechanisms (and their submechanisms) are proposed as potential areas for the analysis of academic discourse in oral presentations and were found to be potential useful markers of successful performance in the OPs of Colombian students in an EAP course for PhD university programs.

The findings in this study might have pedagogical implications. University EAP classes that focus on productive skills could consider the findings in their grammar instruction. For example, the expression of modality with objective-explicit (e.g., it is assumed that) mechanisms could be taught as a key component in writing, and the use of subjective-implicit (we deem this x important) forms as similarly important in speaking. Not surprisingly, grammatical correctness is still favoured in many EFL or EAP contexts, underestimating or ignoring pragmatic aspects like register, sense of audience, or information simplification. EAP textbooks like Reinhart’s (2005)Giving Academic Presentations or Anderson et al.’s (2004)Study Speaking are examples of materials that present grammar in structural and functional terms. Also, the identification of how students modalize contents and include glosses to clarify content, along with the definition of grammatical and pragmatic criteria, could be implemented in the creation of assessment tools that describe levels of oral performance.

The use of a small corpus is one of the limitations of this study. The strategies identified to modify content cannot be claimed to be representative of this population’s oral competence or to reliably discriminate oral performance levels; on the contrary, it could be argued that the findings are merely idiosyncratic. Thus, it needs to be asserted that these mechanisms are indicative, but not conclusive. A second limitation in the methodology was the limited number of strategies to validate the transcriptions and discourse analyses. I transcribed, revised, and analysed the corpus, and none of the processes involved included other raters. The transcription and revision processes were simple and did not need a high degree of detail or tagging; however, my interpretations could have been influenced by my role as teacher, above all in the definition of levels of performances. Finally, the lack of information about the students’ levels as measured by a standard proficiency test was a third methodological drawback.

However, notwithstanding the limitations, the general goals of the study were met, especially given that the analysis of parallel written and spoken sentences by the same authors worked reasonably well in the identification of linguistic devices for mode change. Future follow-up studies will focus on modalization and code glosses in combination with other relevant aspects not considered in this pilot study. Firstly, I will include medium achievers in the comparisons and analyse the three groups using statistical techniques (e.g., MANOVA or regression analysis) to identify how different mode transition devices are related to performance level. Secondly, I will include a contrast between disciplinary fields (e.g., hard vs soft disciplines). Manual analyses of the corpus have shown that the use of these mechanisms could be explained if the students’ disciplinary fields were also considered. Finally, qualitative analyses will also include the use of nonverbal aspects (e.g., gestures, positioning, use of slides, etc.). In the videos, these nonverbal aspects oftentimes appear in coordination with glosses or modalizations, probably given their facilitative role in the comprehension of content.