Introduction

A very asymmetrical conflict among various sides of government, irregular armed groups, and urban crime groups has been developing on the streets and in the schools throughout Colombia. English teachers may argue that learning English is good for their students’ future professional careers and that it helps them to become self-sufficient, but English teachers rarely engage in classroom discussions related to the ongoing conflict or any other social justice issues, such as bullying, racism, classism, and other forms of discrimination (Pedro1, August, 2016). In light of Colombia’s Ley 1732 that stablishes Cátedra para la paz (Curriculum for peace) (República de Colombia, Ministerio de Educación, 2004), which optionally guides teachers to employ pedagogies of peace in their classes, María (pseudonym), an English teacher, wondered how her English class could engage her students in learning while thinking about national and international social issues.

Teaching English as a foreign language should not only be about teaching the language for the sake of language learning, but also about empowering students to discuss issues that are related to their local context (Morgan & Vandrick, 2009). While some English teachers have striven for more engaged thinking, especially about issues related to Indigenous populations and other marginalized communities (Usma, Ortiz, & Gutiérrez, 2018), some think it is fundamental to engage students specifically in peace education because it allows us to connect across differences (Gould, 2013). María (pseudonym) expressed that her personal and professional goal is to conscientize her students about local and national social injustices by tapping into their perceptions about peace and encouraging them to look for possible solutions. In order to explore these ideas more deeply, María and I conducted a collaborative research project. We posed an overarching research question that guided our inquiry: How can a social justice-oriented approach be used in the English classroom for the purpose of creating awareness of local and global social realities?

María gathered artifacts from the classes, such as photographs, videos and written pieces to reflect on her own pedagogical approach. She also recorded an audio journal to describe these practices and then discussed it with me in order to prepare the subsequent lessons. As a critical friend, I looked over the artifacts, listened to the audio journals, and gave recommendations for classroom activities. The interactions between María and me were important because they led to the collaborative creation of the lesson plans she used with her students.

Based on our observations and conversations, María and I found that her students became more aware of and responsive to the country’s realities, the Colombian conflict, and some of the inequalities they were facing in the school and in their neighborhood. The students also learned how to use the topics explored in class to express their ideas and thoughts about the conflict by making a connection to other global issues. From María’s audio journal and reflections, themes related to the students’ conscientization of global and local social problems emerged along with an urgency to solve them and have a positive impact on their communities.

Although María experienced several constraints and difficulties in carrying out this project, she found that her emerging pedagogy changed her students positively. Toward the end of the academic year, students commented how learning English with a social justice focus made them realize how this could be important, not only for economic purposes but also to conscientize others and solve ongoing problems in their communities. As a critical friend, I had the opportunity to give more personalized feedback on classroom practices as I learned more about María and the students’ personal, professional, and academic lives.

In regular conversations with María, we discussed prevailing teaching English practices, whose main aim is economic mobility rather than social justice. We concluded that English seems beneficial for the students’ professional future, but rarely for addressing Colombian social issues. It is only in the past few years that these topics have permeated English teacher education in Colombia (Sierra Piedrahita, 2016), and María extended this social justice sentiment from the teacher education realm to her EFL classroom.

Theoretical Framework

This collaborative research project was informed by three main conceptual lenses: social justice, critical pedagogy, and globalization. In this section, I will explain how these three theoretical underpinnings critically question the status quo and how the subject matter becomes meaningful when students are able to connect their daily life experiences to broader problems of power in society (Macrine, 2009), which, for the purposes of this project, were treated as mainly caused by globalization.

Social Justice

Social justice as a concept is troublesome because it is not fixed; it has multiple meanings and has been conceptualized in different forms depending on the field (sociology, philosophy, etc.). Likewise, achieving social justice is a complex and challenging task for any society and for humans that requires us to strive for social transformation (Johannessen & Unterreiner, 2008). Capeheart and Milovanovic (2007) argued that social justice is not a narrow system that looks for justice for a single individual, but a societal one; thus there is a need to re-examine the ideas of dominant and nondominant justice, and how inequalities affect people or groups. In order to understand the many inequalities present in our daily lives, Nieto and Bode (2012) discussed social justice as a means of treating all people with respect, fairness, dignity, and generosity.

In his seminal piece, Rawls (2001) discussed justice as fairness and how society’s political, social, and economic institutions fit together as a unified system for cooperation across generations. Social justice must therefore be a structure of modern constitutional democratic states to rule the citizens’ actions in benefit of the civil society (Rawls, 2001). Other thinkers have praised human capabilities development in lieu of focusing efforts solely on achieving equal distribution of goods and resources (Morris, 2002; Nussbaum, 2003). In addition, Zajda (2010) proposed the concept of justice as a set of principles encompassing economic, legal, and political dimensions guided by a sense of responsibility to work with others. This implies that social justice must contribute practically to precise action in real-life contexts that feature equal distribution of benefits within society via societal principles. In an earlier publication, Miller (1999) focused on fairness, suggesting three principles to understand how societies engage with it: outcomes of distribution according to need, distribution according to claiming rewards based on performance, and distribution on the basis of equality. Others argued that there cannot be social justice without cognitive (epistemological) justice (Santos, 2007, 2014; Visvanathan, 1997), that is, unless the plurality of knowledges is recognized. Thus, social justice should not be merely treated as a single philosophical concept or a theoretical construct. Moreover, in the context of education, social justice treatment should instead be based on what it can bring to educational practice.

While social justice as a concept may vary between authors, they agree that education for and about social justice has generally been considered a reasonable way to engage students in discussions about the inequalities they live through. Teaching for social justice is therefore teaching for educational equity as teachers fight for a more open and just world for everyone (Johannessen, 2010; Ukpokodu, 2010). Mthethwa-Sommers (2012, 2014) posited that, although some social justice education theories argue that schools may serve as transmission tools of the dominant culture thus perpetuating inequalities, other theories demand that schools serve as spaces to transform oppressive policies and foster social justice and democracy. Significantly, promoting social justice follows an agenda of its own, under specific goals prioritizing “equal participation of all groups in a society that is mutually shaped to meet their needs [...] in which distribution of resources is equitable and all members are physically and psychologically safe and secure” (Bell, 2007, p. 1).

Cochran-Smith (2010) already discussed a contemporary theory toward teacher education for social justice in which children should receive a world-class education and become a well-qualified labor force to preserve their nation’s economy and be able to compete in a multicultural world. Students in today’s classrooms are diverse: They come with a myriad of linguistic and cultural backgrounds that need to be asserted, valued, and recognized as equal. Many countries are considered diverse, and Colombia is not an exception. Students there come from different backgrounds (Afro-Colombians, peasants, Indigenous-descent, mestizos, among others), which has led to suggest that culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogies be used (Ladson-Billings, 1992; Paris & Alim, 2017) to pursue a more equitable education.

It is important to highlight that curriculum studies have not focused only on social justice from different teachers’ and students’ perspectives in relation to their communities (Picower, 2012) but also on how peace education and democratic citizenship (Hastings & Jacob, 2016) are gaining more attention in the teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL) research agenda due to efforts by social responsibility special interest groups (Chang, 2018).

Critical Pedagogy

Like social justice, critical pedagogy is complex to define. It involves more than learning some pedagogical techniques, as it looks beyond classroom practice because it “believes that nothing is impossible when we work in solidarity and with love, respect, and justice as our guiding lights” (Kincheloe, 2008b, p. 9). Inspired by critical theory, on one hand, critical pedagogy functions within the social embeddedness of education, in which identity becomes an active construction by the individuals who transform themselves and their cultures in a natural social and political process of becoming human (Wardekker & Miedema, 1997). On the other hand, critical pedagogies, critical peace education, and especially engaged thinking argue that education can provide individuals with the necessary tools to improve and strengthen themselves in order to create a more egalitarian society (Kellner, 2000). This helps to bring about social change by empowering students to become more critical of power relations. Giroux (1994) states that “pedagogy in the critical sense illuminates the relationship among knowledge, authority, and power” (p. 30) and points out how questions of audience, voice, power, and evaluation actively work to construct particular relations between teachers and students, institutions and society, classrooms and communities.

Moreover, some scholars claim that critical pedagogy in education must commit to empowering the powerless to become active critical producers of meanings in order to transform themselves and those conditions which perpetuate injustice and inequity (Kellner, 2000; Kincheloe, 2008a; Mclaren, 1988). This means that education can provide individuals with the necessary tools to strengthen themselves in order to create a more egalitarian society, while peace education can bring about social change. Additionally, teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) can empower students to use language to discuss issues of national importance and challenge oppressive epistemological mindsets. In this regard, Al-Amri (2011) posited that a critical perspective in TESOL education might empower students and generate social-cultural consciousness as they improve their metacognitive skills. Meanwhile, in EFL education Sung (2007) suggested that teachers need to engage critical teaching practices by localizing pedagogy as they question issues of power and promote social justice to challenge the monopoly of Western English teaching.

Critical pedagogy has been continuously working on promoting self-reflexivity to connect theory and practice in the field of applied linguistics and thus to try and shift how language education can be more politically accountable to society (Pennycook, 2001, 2008, 2010). Since its inception, critical pedagogy has focused on questioning power relations while facilitating the students’ processes of sensitization and conscientization to connect their daily life experiences to larger problems of power in society (Freire, 1970; Macrine, 2009).

Globalization

In the last decades, we have seen processes of interaction and integration among peoples and enterprises across the globe with the purposes of connecting, trading, and investing in goods and services. After WWII, we have experienced an increased awareness of what it means to be global and pursue collective progress. In this regard, Meyer (2007) distinguishes two meanings for globalization. Firstly, the idea of interdependencies and rates of transactions around the world, in which global production and commodities are exchanged with cross-national investment patterns. Secondly, the idea of a widespread consciousness of interdependence and the embeddedness of the local and national within a worldwide society. These processes of interaction and integration generate what is called a world culture in which we belong to each other, we are connected economically and culturally, as Meyer, Boli, Thomas, and Ramirez (1997) argued:

worldwide models define and legitimate agendas for local action, shaping the structures and policies of nation-states and other national and local actors in virtually all of the domains of rationalized social life -business, politics, education, medicine, science, even the family and religion” (p. 145)

This brings about an international society that tends to be more interdependent in an effort to be similar, homogenous and legitimating itself to apply universal models applicable worldwide.

Globalization as a multifaceted phenomenon has become a symbol of postmodernity in which new dimensions of social and economic stratification have emerged with equity and equality implications for educational opportunities (Zajda, 2010). These opportunities are created for new markets under primarily neoliberal ideas for the distribution of educational resources via free tax agreements and individual self-interests (Banya, 2010). English language education has become part of this global trend. We see more English language education across the globe (Block & Cameron, 2002; Pan & Block, 2011; Rubdy & Tan, 2008; Yusuf, 2012), and Colombian classroom practices and linguistic policies are not exceptions to this rule (González, 2010; Usma, 2009b).

Language classroom practices and policymaking decisions are reflections of the globalization neoliberal-style that has permeated the English language teaching (elt) industry around the world. Furthermore, because English has become a tool for modernization, teaching and learning the English language has turned it into a device for global communication, which has led the acceptance of multiple varieties of the English language as its contact with speakers around the world grows (Gnutzmann & Intemann, 2005). For Block and Cameron (2002), this language expansion occurs because language is the medium of communication, social interaction, and social relations, and it is used in networks around the world, which connect the local with the global. Block and Cameron (2002) also state that “distance is not an issue for these non-local networks, but language remains an issue of some practical importance: global communication requires not only a shared channel (like the internet or video conferencing) but also a shared linguistic code” (p. 1).

The way the English language is connected around the world exemplifies how globalization affects different countries in different ways. It has affected language policy in Turkey (Kirkgöz, 2009), hiring practices in Korea (Jeon, 2009), the rise of English language businesses in Ukraine (Smotrova, 2009), teaching practices to internationalize education in Vietnam (Dang, Nguyen, & Le, 2013), and student mobilization in China (Xu, 2013). While globalization has permeated many aspects of our lives in recent decades, organizations, ministries of education, stakeholders, etc. usually represent the interests of only some, not all (Peterson & Helms, 2013).

The entire ELT industry has been affected rapidly by globalization as well, which has brought about positive effects, such as the commodification of English (Heller, 2003). It has also influenced the teaching and learning practices within many institutions and organizations that provide English education (Shankar, 2015). However, although advances in technology have made communication easier and faster, and subsequently interaction with other cultures has become an effortless task for English students (Shankar, 2015), globalization has also encouraged dependency on others. Alfehaid (2014) proposed that this dependency means teachers may not be able to be sufficiently creative when using cutting-edge technologies and appropriate materials for their lessons.

Language Instruction for Social Justice-Oriented Pedagogy

For several years now, EFL teachers have been focusing on teaching linguistic structures and forms using communicative methods, and a few have purposefully used social justice approaches to develop conflict resolution skills (Hastings & Jacob, 2016). However, EFL education can empower students to use language to discuss issues surrounding direct physical violence, structural violence, and social injustice. Morgan and Vandrick (2009) argued that the English language classroom is a good site to discuss peace because the classes focus on language and communication; the English class offers the perfect opportunity to “develop pedagogies addressing [...] conflict and the dehumanizing language and images that promote it” (p. 510). In addition, Arikan's (2009) study in which grammar was contextualized through environmental peace education activities to raise students’ awareness of global issues demonstrated that the approach was an effective strategy for foreign language teaching. However, he noted that “the activities suggested are more likely to be used for practice and production phases (to reinforce concepts and solidify the new language) because they require students’ active participation and engagement” (p. 96). This highlights that pedagogical activities should target specific issues that can connect local problems to global concerns.

While social justice and critical pedagogy approaches to education have been used in classrooms for some time, research, policy, and practices on how these approaches may be applied in ELT classrooms are rare. According to Hastings and Jacob (2016), English language learners are often on the margins of society; therefore, those who teach them must advocate for their needs. Corson (1999) suggested that social justice should critically acknowledge human diversity and be recognized in policy decision-making. However, English-only policies in multilingual contexts are quite common (Davis, 1994; Kamhi-Stein, Maggioli, & Oliveira, 2017; Oliveira, 2014). Unfortunately, these policies are not in line with the reality of most ELT classrooms (Hornberger, 1988; Jong, Li, Zafar, & Wu, 2016; Usma, 2009a).

English-only ideologies that promote the status of English as superior to other languages and that do not represent the interests of marginalized and racialized people are common in language teaching. For example, in Colombia costly bilingual schools continue to propagate the idea that English is best, marginalizing Indigenous languages in the process (de Mejía, 2006). Mohanty (2009) also argued that a power imbalance exists among languages to the detriment of the languages of marginalized peoples. He reiterated that English in many multicultural contexts has been portrayed as superior, resulting in it killing other languages, including Indigenous ones. Conversely, Mohanty’s (2009) premise suggests that if national governments adopt a multilingual approach that values and acknowledges all languages, social justice will be furthered, because the languages (and therefore views, voices, and worldviews) of marginalized groups will be privileged and protected.

Scholars are increasingly interested in exploring how ELT can be used to foster social justice orientation and practices in students. For example, Jakar and Milofsky (2016) recently used the English classroom as a site to discuss and transform conflict. They conceptualized peacebuilding as a process of establishing relationships by seeking individual and collective solutions and proposed a content-based curriculum that emphasizes multiple-perspective conversations about conflict involving dialogue skills, creativity, narrative, and student empowerment that can provide space for discussions around, in, and on conflict (Jakar & Milofsky, 2016).

Meanwhile, Medley (2016) argued that, for teachers to successfully engage in conflict transformation, peacebuilding orientation must be a part of their professional teacher identity. She drew on narrative inquiry to explain how her identity and personal experiences allowed her to be a teacher who works on peacebuilding initiatives in the English classroom (Medley, 2016). She has worked with trauma-affected students from several countries, including Nepal, Sri Lanka, Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Kenya, Israel, and Palestine to understand their collective experiences of conflict and to try to help bring hope, restoration, and healing (Medley, 2016).

Within social justice-oriented approaches to research and practice, peace and peacebuilding have encountered a space to dialogue with language education. Oxford (2013, 2017) took direct steps toward peace by designing peace language activities that were field-tested in EFL teacher education classes in Argentina. She provided empirical evidence that structures of violence can be overcome in EFL classes if peacebuilding perspectives are promoted in different contexts by discussing six crucial dimensions for humanization: inner, interpersonal, intergroup, international, intercultural, and ecological (Lin & Oxford, 2011; Oxford, 2013, 2017).

Although Colombian EFL educators can learn from this Argentinian experience, they can also examine problems in their local communities and discuss them using existing activities to solve those problems. Colombia has already worked to integrate community issues into its curriculum with the programa de competencias ciudadanas (Colombian program of citizenship competencies) (República de Colombia, Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2004). Following the program’s implementation, Chaux, Lleras, and Velásquez (2004) and Chaux et al. (2008) both explored possibilities for how to use these competencies in the classroom. This is a resource that the EFL community in Colombia has not utilized to its full potential, but it could benefit the marginalized communities in urban and rural areas alike, as recently proposed by Peláez and Usma (2017) and Sierra Piedrahita (2016).

In Colombia, social justice as a concept has not been discussed directly but has permeated in different forms such as cooperative learning to foster dialogue and reflection (Contreras & Chapetón, 2016), learning for personal growth and social awareness (Parga, 2011), learning to address aggressive behavior (Castellanos, 2002), learning to establish personal connections while creating argumentative essays (Chapeton & Chala, 2013), and learning to encourage critical participation using songs in the EFL classroom (Palacios & Chapetón, 2014).

The research above shows that, in addition to learning important technical aspects of the English language (such as grammar, pronunciation, etc.), EFL classes can help students connect with the Colombian reality as well as global issues. Ongoing discussions among Colombian teachers, scholars, and researchers have demonstrated the need for teacher education programs, professional development, and curriculum design that better reflect the realities of the Colombian context.2 Teacher education programs have been studied to understand how social justice can help language teachers to develop a political view of their work and effect change in different school contexts in Colombia (Sierra Piedrahita, 2016). However, much more needs to be done in the English language classrooms of post-accord Colombia, hence the collaborative action research presented in this paper.

Method

First, I must declare my positionality and my relationship with the English teacher and her students in this research project. I entered into it as a critical friend (Costa & Kallick, 1993; Elliot, 1985) when I met María (pseudonym) in 2015 in Colombia. We were both concerned about how ELT would be involved in the peace agreement process that was taking place in Colombia at that time. We set out a collaborative action research project with the intention of solving some of the problems that occur in an institution or community with a practical orientation (Hinchey, 2008). This research took place in a community in the southwest of Colombia’s capital city which is densely populated and has high rates of internal immigration from other regions, and most of its inhabitants fall into the government’s low socioeconomic status designation (Secretaría Distrital de Planeación, 2009).

Co-Researchers

The participants in the study were ninth-grade students (around ages 14-15) in an EFL class in an urban public school attended by many disadvantaged students. The data collection began in August of 2016 and continued until December 2016. María decided to take action in her class by using social justice themes (e.g., bullying, classism, racism, and others) while teaching English. She and her students discussed what themes they wanted to explore based on their experiences in and out of school.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection included 13 teacher self-observations recorded in a notebook in the form of diary entries, 12 reflections in the form of audio journals, and ongoing semistructured interviews with six selected students. María made reflections in her diaries, which she shared with me in the form of an audio WhatsApp message for discussion and feedback once a week. The focus of the diaries was to reflect on her own pedagogy and discuss which activities worked well for students and which ones were more challenging, so she could adapt accordingly for the subsequent class.

Informally, she asked her students for feedback in order to get ideas for the lesson plans she prepared, but six specific students were key in the decision-making process as she interviewed them twice a month to get specific contributions on themes and activities for the class. Fewer informal interviews were conducted with parents (during parent-teacher meetings) to understand the students’ lived experiences outside the classroom, including their struggles and problems. María wanted to include some of these experiences as part of her lessons, for example one day she asked students to work on a project about unemployment as this was one of the most common issues parents mentioned during her meetings. Additionally, the principal met María regularly to give her feedback and encourage her to continue her work as she had become an inspiration for other teachers. He asked her to continue doing her activities as these were becoming role models for other teachers who were working on other issues, such as recycling, global warming, teenage pregnancy etc.

After the data were collected, managed, and processed, I used Nvivo 10 software to explore the emerging themes as I used content (Berg, 2009) and thematic analyses (Ryan & Bernard, 2000) of recurring codes/nodes. As a critical friend and researcher, I developed a subjective interpretation of the nodes through a systematic classification process of identifying patterns (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

For this action research project, not only did we focus on triangulating the data (Fusco, 2008), but also following a poststructuralist approach called crystallization in which the students, teachers, and I discussed the emerging themes. Crystallization (Fusco, 2008) has the potential to provide more in-depth and complex understandings of how the social world works. Here, we all see ourselves as researchers, we see the extent to which text validates itself as we engage more deeply with the data. Richardson (2000) also invited researchers to see data as if they flowed within a crystal, reflecting colors and patterns, and to consider them as refracting the light and giving off different shades. In the same way, crystallization represents different angles from different views that allow for three-dimensional data analysis, just like a prism reflects the external into the internal and then refracts again to the external. As such, María and I believed the power of many voices to have been heard, with many stories to consider in the research process.

While María collected the data, she discussed them with me as a critical friend in order to reflect on her practices and prepare the next lessons. I looked over her lesson plans, listened to the audio journals, and gave recommendations for classroom activities. The outcome of each interaction between me (as the critical friend) and the teacher was used for subsequent lesson planning. During this constant monitoring, we all collaborated (me, remotely in a large North American city and María with her students in Bogotá) to determine the criteria for selecting the most appropriate activities to address social justice themes, especially what language skills must be used when discussing problematic situations and when reflecting on how they all connect to global circumstances.

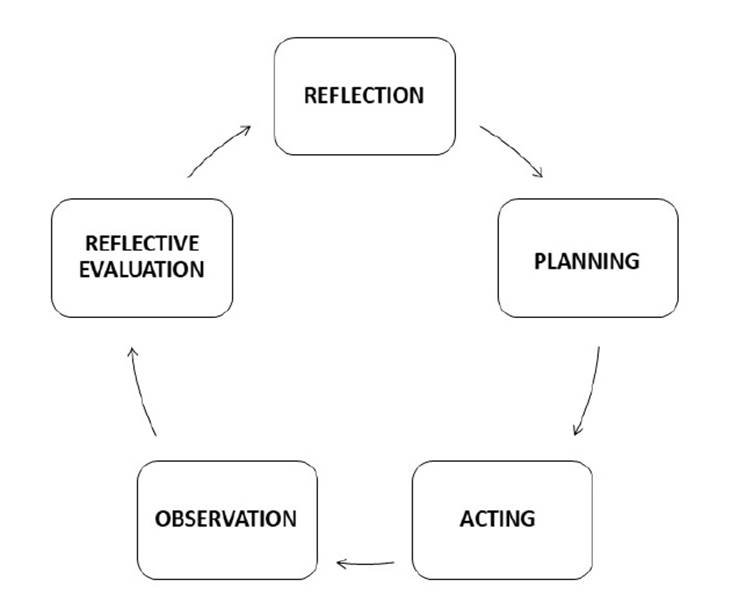

I describe the action research process as a continuous cycle (Figure 1). There was an initial reflection stage in which María and I discussed problems in the classroom or any other issues that arose. Then, she prepared a draft lesson plan that she discussed with her students and me. Subsequently, she taught the class according to the plan and entered into a process of self-observation. After the class, María and I got in contact and discussed the pros and cons of the lesson plan and how it could be improved. Finally, another process of reflection based on previous evaluation took place, and María planned another lesson.

English in Action

Given the constant struggles María’s students regularly experienced, she and I had various conversations about how to bring different pedagogies into the classroom that could address their concerns. She decided to call this pedagogical and research project English in Action because, she said, “I believe that in order to learn, students need to put things into action”. Then, we both agreed to collaborate on creating activities that considered the information the students shared about their own violent experiences in and out of school. In this section, I will give a brief overview of the activities that were conducted in the classroom in order to address María’s concerns and explore how this collaborative action research experience might be a sound example for other colleagues to follow.

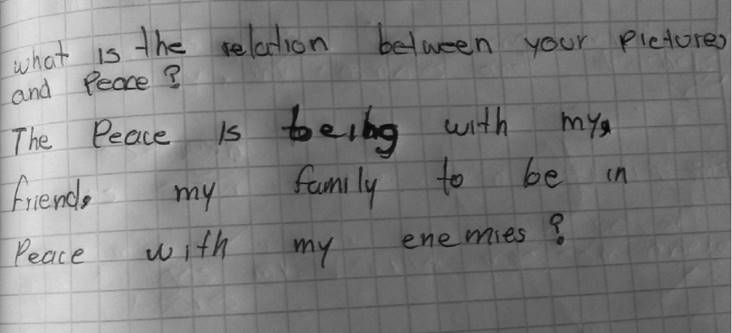

María created some activities to discuss bullying issues and how to address them from a peace education perspective. The first attempt was to ask students what the concept of peace was for them. Students got into groups of four people and discussed orally what the meaning of the word peace was for them. Some students sketched their ideas on their notebooks while María was monitoring their work and giving them comments on what they were discussing. She asked them to summarize their ideas on a few words or drawings in their notebooks (see Figure 2) and shared their conceptualizations with their peers.

After some consideration, María realized that the students were having vague ideas about what peace is, she concluded that discussing abstract concepts were not sufficient to have a real impact on students’ lives. She wanted her students to really explore more in depth their own ideas and engage them in concrete actions to seek transformation. Subsequently, she and her students collaborated to create activities that involved taking concrete actions. Together they had several discussions about what to do within the school, but also how to have an impact on the community.

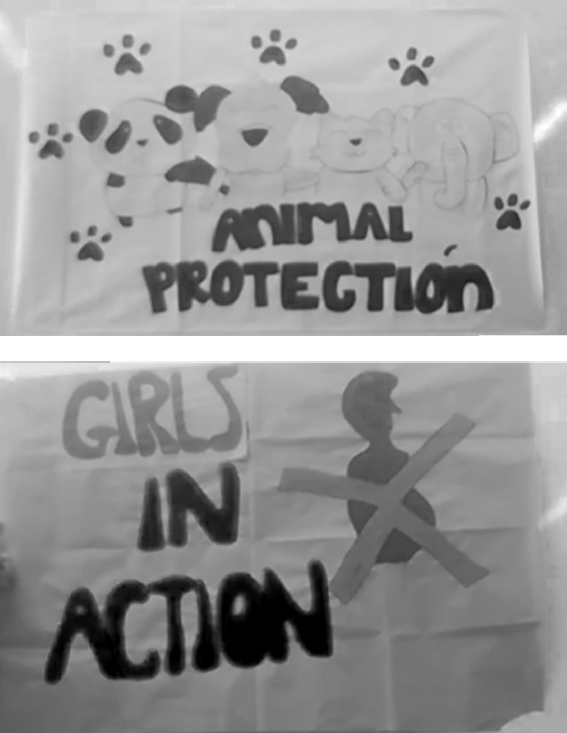

As a result, students created organizations that sought to support people in the community. They generated ideas for protecting animals, inviting students to avoid illegal drug use by practicing soccer, supporting pregnant adolescents, and others. During the process of this task, each student organization had to write its mission, vision, and goals, and María provided scaffolding through error correction in grammar and punctuation. Students did a series of in-class presentations with posters (see Figure 3) to practice speaking the language in front of their peers and get feedback. Some of the groups actually went into their neighborhoods and raised money to provide food to homeless people and buy dogfood for dogs. Others went around the school and created awareness about drug addiction and teenage pregnancy.

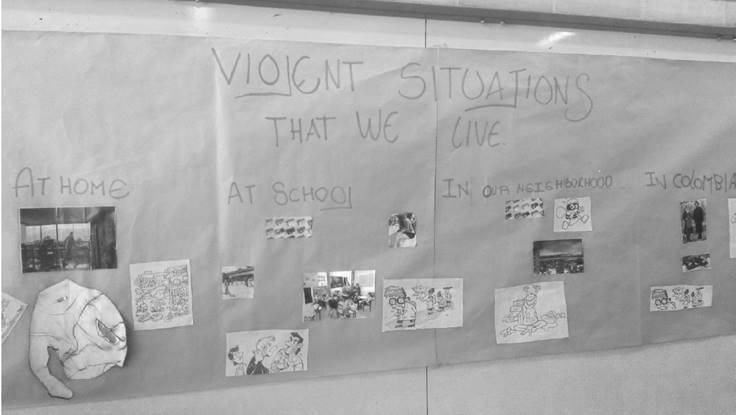

Another activity carried out was to examine the different areas of life where students believed there was aggressive behavior. Students researched what was happening in their communities and became aware of the many sectors in which Colombians face inequality such as salary and pay, unemployment, intra-family violence, and access to food or water. As a follow up of this activity, they also presented their personal experiences of violence at school and at home in the form of class presentations with posters (see Figure 4). The posters were hung on the school’s walls to create awareness of local, national, and international violence and civil aggression.

One more activity that María did with her students in order to address violence represented in their posters was to create performance sketches based on real-life school scenarios. After several classes, the students and María worked together to create scripts, correct grammar, and rehearse for their performances. When they completed their preparations, the students performed their sketches to different audiences in the school.

Finally, María and her students went through a process of reflection about all the work they did during that academic year. Students’ comments reflected how they gained awareness of different social problems faced by their school, their neighborhood, Colombia, and international communities. Various teachers from other subjects took initiatives to create their own artistic projects based on what has come to be referred to as paz con justicia social in Colombian education circles, which I have translated to “peace with a social justice lens.” In the following year, other English teachers in the school created projects to encourage students to present positive experiences from their neighbourhoods while doing presentations to promote intercultural awareness.

Results

In response to the main research question of this collaborative action research project, namely, how a social justice-oriented approach can be used in the English classroom for the purpose of creating awareness of local and global social realities, I found evidence of the following emerging themes: 1) normalization of violence and how pedagogies can counter such normalizing discourse, 2) students becoming more responsive to the Colombian conflict and social inequality because they are connected with similar global issues, and 3) the impacts of English activities on the community beyond the classroom as an act of praxis.

Violence Normalization and Counter-Narrative Pedagogies

First, data revealed that aggressive practices have been normalized and have become part of the students’ everyday lives. Overall, bullying was not seen as a negative factor in students’ relationships but rather a sign of friendship. One student shared the following comment with the teacher: “Profe, pero hacerle bullying a ella no es malo, no ve que somos amigos y eso le va a hacer bien” [But, Teacher, bullying her isn’t bad. Don’t you see that we’re friends, and that it’s going to do her good?]. María also commented in her audio reflections on how students saw their violent attacks on each other based on their Colombian soccer team preferences as normal. Additionally, she commented on how frequently her students mocked each other when they made grammar or pronunciation mistakes in English: “Veo cómo esta niña le dice a la otra: “Es ‘she plays,’ no ‘she play,’ boba.” [I can see how this girl tells the other, “It’s ‘she plays,’ not ‘she play,’ you stupid girl.”].

Given that the behaviors María witnessed are consistent with similar research conducted in history and other classes in Colombian classrooms (Padilla & Bermúdez, 2016; Villar-Márquez, 2011), we can see that these normalized discourses have occurred not only in a specific class but across the school spectrum. In one of our Skype meetings, María made this connection, stating that, in her many discussions about these topics with colleagues from the Colombian teachers’ union (Federación Colombiana de Trabajadores de la Educación [FECODE]), she learned that most teachers (not only English teachers) were grappling with this normalization in the classroom and looking for ways to respond pedagogically.

However, the evidence showed that, toward the end of the academic year, the students demonstrated that participating in these social justice activities -especially the performance sketches- not only helped them to improve their English skills but to challenge the normalized discourses of violence targeted by the activities. Laura (pseudonym), one of the students, made this comment in one of the interviews: “Profe, haciendo estos diálogos me ayudó a entender que no debo matonear a mis amigos. No, profe, eso no está bien. [Teacher, by doing these performance sketches I got to understand that I shouldn’t bully my friends. No, Teacher. That’s not good.]”. The evidence also showed that María’s social justice-based approach empowered the students to become advocates for peace and encouraged them to learn more about other cultures: “Yo veo a los muchachos más empoderados y con ganas de aprender más de otras culturas. [I see the kids more empowered and eager to learn more about other cultures.]”. This demonstrates how English brings positive effects as students commodify their English assets (Heller, 2003) to connect with and learn from other global contexts.

Social Awareness and Glocal Connections

As a second emerging theme, the data collected showed evidence that students were able to make international connections. Many students realized that by learning English they would be able to understand other cultures and learn from the struggles other countries have been through. The topics discussed in class allowed them to express their ideas about what transpires in Colombia (poverty, unemployment, immigration, violence, etc.) and how it is connected to their own conceptualizations of peace and other parallel global issues. During one of the presentations about the students’ perceptions of violent situations locally and globally, María engaged her students in in-depth discussions about what it means to be poor in Colombia compared to other countries such as India. The evidence suggested an emerging theme related to this engaged thinking (Gould, 2013), as María detailed how students saw socioeconomic classes in a more subjective manner than at the beginning of the school year with a greater basis on their personalities and beliefs about global and local struggles. In other words, the students did not discuss peace or social justice as strictly abstract ideas, but in terms of concrete actions needed to address immediate social issues, especially those in their lives and communities. As one student stated, “Profe, ahora sí entiendo por qué tenemos que hacer algo YA para resolver el problema de pobreza local… mundial). [Teacher, now I understand why we need to do something NOW to solve the issue of local… global poverty.]”.

The students’ perceptions were always at the center of each class because María wanted them to focus on turning their ideas into concrete actions. For the students, these actions mean having conversations about Colombian social issues, violence and discrimination. For example, María told me about one class in which some students discussed in small groups about the Colombian problems, for example they talked about floods happening in some of the most vulnerable communities of Colombia, unemployment among immigrants from Venezuela, and the peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), and how they all connected to issues in the Middle East, such as the Syrian conflict and immigration to Europe and North America. Alfehaid (2014) stated that it is through these types of discussions that students and teachers can learn how globalization can have a positive effect on them. In this case, María and her students realized how social media and other media outlets have allowed them to learn about both foreign and local issues that they had never heard of before, thus making them more aware of and responsive to social problems.

Yo me acuerdo cuando los niños me contaban lo de que hay muchos inmigrantes de Venezuela en el barrio y yo les decía que eso también pasa en México a Estados Unidos y en Siria hacia Europa. No somos ajenos a eso. [I remember when children told me about the Venezuelan immigrants in our neighborhood, and I told them that this also happens from Mexico to the United States and from Syria to Europe. We are not alien to that.]”.

Some students argued that learning about other cultures and their problems would not have been possible if the teacher had not encouraged them to learn English and use social media to learn from others.

Community Praxis

A third theme that was observed in the data collected as well as in María’s regular communication with me as a critical friend, which showed evidence that social awareness created in class was the result of María designing and implementing her classes with an aim to encourage students to care about others and of she sawing the project through to the end of the semester. María expressed that all her work was based on her personal goals, one of which she brought up in the following excerpt: “I want my students to be happy and also learn the linguistic skills to become social agents of change”). She also expressed her commitment to working to bring about social change by using a social justice-based approach in her classes that translated to concrete actions in her students’ communities. She wanted to guide her students to go beyond thinking abstractly about certain concepts and push them to act to have an impact on society.

Using various pedagogical strategies such as drawing, and scripting dialogues, María engaged her students to both learn English and discuss social issues. Some students were sparked to organize themselves to address poverty, drug addiction, gang-related activities, and other social issues in order to create real organizations that raise funds and bring real actions to fruition to solve real problems. For example, María described how one of the student organizations looked at soccer as a way to help children in the community to stay away from gangs, and another group of students collected money to buy food for stray dogs and cats in their community. The students shared their experiences in classroom presentations conducted in English, while getting both linguistic feedback from the teacher and encouragement feedback from their peers. Various students commented on how these initiatives promoted creativity and how they helped them to reinforce what they learned in class. “Tomamos las ideas de la profe e hicimos este mural de la paz con el profe de ética. [We took the [English] teacher’s ideas, and we made this mural about peace with the Ethics teacher.]”. This evidences how activities are not carried out in a vacuum but in connection with society in the form of what critical pedagogy has called praxis (Bajaj, 2015; Bajaj & Hantzopoulos, 2016; Freire, 1970). In other words, the activities enabled students to engage in practical learning experiences, hence María’s project name -English in Action.

Finally, I also found that María felt her approach to teaching English gave her students hope about their future because they took part in real social influence in their school and real changes in their lives. By the end of the school year, the students felt that they were more socially aware and believed their future personal and professional lives should have a positive impact on society: “Hoy siento que a pesar de las dificultades que tenemos, ellos han aprendido a ser mejores seres humanos …y lo mejor es que están aprendiendo inglés. [Today, I feel that, despite the difficulties we have, they (the students) have learned to be better human beings […] and the best thing is that they are learning English.]”

This sentiment is in line with the critical pedagogy tenets holding that classroom activities can further critical consciousness for human and social development (Freire, 1970; Kincheloe, 2008a, 2008b; Lloyd, 1972; Mclaren, 1988, 2003) because they empower students to learn from local and global struggles and look for possible solutions.

This project showed that collaborative activities that engaged students with different activities promoted social awareness while providing the language skills necessary to address social injustice. The classroom and research efforts between María and I support closing the gap between research and practice by promoting dialogue between the creators and users of research. Doing collaborative action research in the classroom supports the social research agenda necessary in teaching education programs in Colombia (Escobar, 2013). This project seeks to add to the body of knowledge at the intersection of global issues and social justice education in ELT in a country where dialogue is still needed between the various actors in social conflict, which includes teachers, students, and other community members.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper has shown how teachers and students may benefit from co-constructed activities implemented in the classroom setting. In this case, they increased María and her students’ awareness and understanding of the many inequalities that some communities have faced through the years both in Bogotá and throughout Colombia. Also, in a country where the FARC and the government signed a peace agreement, María’s initiatives for classroom pedagogies may empower students to make better decisions to improve conditions in their communities and become better citizens. Such initiatives are timely and beneficial for ensuring a prosperous future for post-conflict education because they demonstrate how social justice issues can be discussed not only in social studies and history classes but across multiple curricula.

One of my reflections on this collaboration was that I discovered the importance of connecting with participants in the research process. I learned a lot about how María has involved her students in the decision-making process and I was truly affected by her work, and now I value the work teachers do even more, specifically in contexts in which it is necessary to validate knowledges that have been previously marginalized or devalued (Santos, 2007).

English in Action as a project has demonstrated the possibilities of how social justice-oriented approaches can intersect with English language education by shedding light on the different ways that students can be engaged to amplify their personal concerns. Other teachers and students in María’s school are already critically examining the many killings of community leaders, intrafamily violence, feminicide, child abuse, and other forms of violence. Although most of the activities María did in her classes looked at Colombian contexts, her students began making global connections to what happens in Latin America and other international contexts. For example, in one of María’s classes while reading about the Venezuelan and Syrian refugee crisis, her students noticed that what they experience on a daily basis is not something they struggle with alone, but that others with similar or worse conditions worldwide have experienced it as well. María’s initiatives have also inspired other English teachers in her school. One teacher at her school began examining how her initiatives could be used to encourage students’ pride in their Colombian heritage by creating social organizations that address social issues in their communities and presenting writing projects about their hopes and dreams for their future lives. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, the teachers at María’s school have begun to make efforts to strengthen ties among them and create interdisciplinary projects that critically examine sociopolitical issues in Colombia and other parts of the world.

In addition to EFL, I believe the findings of this research project are relevant to the fields of international education, social justice education, and TESOL because students can be encouraged to use English language skills to discuss relevant issues for them, their communities, and their families while also becoming advocates for equality, social justice, and peace. Also, although the work that has been done in Colombia on the relationship between social justice and English language education is emerging, it is exemplary as indeed empowers students to discuss issues that are relevant to the current realities of life (Sierra-Piedrahita, 2016).

As a researcher in collaboration with teachers and students, I came to the conclusion that our work must have the capacity for transformation and propose alternatives for a more socially just future. With the quote, “if research does not change you as a person, then you haven’t done it right” (Wilson, 2008, p. 135), I end by saying that I hope our work as researchers and teachers maintains constant curiosity, revolution, and social justice for all.