Introduction

The study of forms of interaction between the teacher and students, and their impact on a positive teacher-student and student-student relationship, offers an advantageous opportunity to better understand how the teacher can develop these essential elements in the foreign language (FL) classroom. As previous studies have shown, the attitudes of students not only toward the teacher, but toward classmates as well, affect motivation and performance in the learning of a FL (Minera Reyna, 2009; Dörnyei, 2002; Swan, 2003). Investigations have found that the development of positive relationships can be actively nurtured by the teacher over time (Eschenmann, 1991). As such, it is important to explore which interactions help build these relationships and to what extent. The three forms of interaction chosen for this study due to their value in second language and foreign language acquisition are positive comments, corrective feedback, and personal thematic discourse. Additionally, due to the transition to the synchronous online classroom as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, further investigation into the impact of the online versus face-to-face setting on the development of these relationships has become an essential component.

As half of the semester was conducted FtoF and half synchronously online due to the emergence of the pandemic, the unique circumstances allowed for the comparison of the two learning environments. Due to this sudden transition into online teaching and the unknowns that we have about teacher-student and student-student interaction in online settings, this study examined three questions regarding differences in the development of the teacher-student and student-student relationships in the FtoF and online classroom. These research questions include the following: (1) In terms of FtoF and online synchronous classes, which has a greater impact on the development of a positive teacher-student relationship? (2) In terms of FtoF and online synchronous classes, which has a greater impact on the development of a positive student-student relationship? (3) How does feedback (i.e., positive comments and corrective feedback) differ from the FtoF to the online classroom?

Additionally, in terms of the impact of the three forms of interaction on the teacher-student and student-student relationship in the FtoF classroom only, that is, prior to the transition to the online classroom, two main questions are explored. (1) Of the three forms of interaction from the teacher examined in this study, positive comments, corrective feedback, and personal thematic discourse, which are the most effective in the development of a positive teacher-student relationship? (2) Of the three forms of interaction mentioned above, which are the most effective in the development of a positive student-student relationship?

To address these questions, students from six different beginner-level Spanish courses at a university in Hawai’i were asked to participate in the study by completing a three-part questionnaire during their final month of the semester with open and closed-ended questions regarding the impact of the online and FtoF setting, as well as the impact of the forms of interaction on rapport with their teacher and peers. After a qualitative analysis of their responses, an important relationship between a personal FtoF classroom, feedback, and the teacher-student relationship was revealed, as well as the importance of personal thematic discourse and positive comments in the development of the student-student relationship. This study concludes with suggestions of various pedagogical implications for when we find ourselves in a situation like the current one in which interaction, essential in the building of positive relationships, needs not only to be incorporated into the FtoF classroom, but in the classroom online as well.

Theoretical Framework

The following section presents research on the role of teacher-student and student-student rapport in the field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) in both the FtoF and online classroom. First, studies on the correlation between rapport, motivation and linguistic performance will be described, followed by research on the impact of these relationships on online learning. Then, studies on positive comments, corrective feedback and personal thematic discourse will be described as seen in both the FtoF and online setting.

Rapport in the Field of SLA

The correlation between the teacher-student and student-student relationship, motivation, and linguistic performance in the learning of a FL has been an important discovery in the field of SLA. The teacher-student and student-student relationship were incorporated in the socio-educational model by Gardner and Lambert (1972) and Gardner (1985) referred to as “attitudes toward the instructional atmosphere.” The impact of the teacher on the attitudes of the students has been investigated by many such as Minera Reyna (2009), Eschenmann (1991), and Dörnyei (2002). Minera Reyna (2009) demonstrated in a study that, among the attitudes of ten students examined in the FL classroom, the most positive attitude was toward the teacher, which correlated positively with their attitude toward their classmates and perseverance in learning Spanish as a second language. Gardner (2001) also proposed that the role of the teacher has a profound influence in the classroom. He found that a fundamental part of student motivation is their attitude toward the school atmosphere, which includes the teacher and their peers. In relation to the “social unit” of the classroom (the combination of the teacher-student and student-student relationships), a study by Dörnyei (2002) found that even when the student has a mediocre attitude toward the tasks, their output and their verbal participation can increase when their attitude is positive towards the course.

Rapport in the Online Classroom

These findings in the FtoF medium also apply to online environments. In the online setting, a sense of community co-constructed by positive teacher-student and student-student rapport has been shown to increase student satisfaction and persistence in the online course (Rovai, 2002a; Pollard et al., 2014). Rovai (2002a) found that the teacher’s role includes promoting a sense of community among students through socio-emotional-driven interaction, among other components, such as by writing empathetic messages or promoting selfdisclosure. Another factor that seems to contribute is social presence. Garrison et al.’s Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework (2000) holds that social presence, or the participants’ ability to project themselves online both socially and emotionally, is one of the essential elements in building community and promoting meaningful interaction. They claim that it is within the socio-emotional environment that students are better able to construct meaning of the course material (i.e., cognitive presence). Likewise, in a survey completed by 137 university students taking online courses, Pollard et al. (2014) discovered that instructor social presence impacts both the development of classroom community and students’ positive perception of their online course, allowing for enhanced academic learning. Finally, in a study by Sher (2009), the author observed that encouraging participation in discussions, giving feedback, and treating students with respect are effective in fostering rapport between teacher and peers. In fact, Sher’s study, which consisted of a survey completed by 208 students across multiple disciplines in webbased university classes, revealed that not only is teacher-student interaction one of the most critical components in student satisfaction but also in fostering a positive learning environment which promotes a sense of community among students.

Positive and Corrective Feedback and Personal Thematic Discourse

The effects of interactions between students and the teacher such as positive comments, corrective feedback, and personal thematic discourse have all been of interest in the development of these essential relationships. Positive comments are a form of interaction by which the teacher can demonstrate their confidence in the student and lower their affective filter which promotes learning (Hawk et al., 2002). In fact, studies in the online setting have found that praise and encouragement, among other types of interactions that minimize the feeling of distance between the teacher and students, lead to greater learning (Swan & Shea, 2005). Likewise, constructive and supportive feedback has been shown to be a principal component in building trust and community in the online classroom (Rovai, 2002a). Hackman and Walker (1990) found in a study involving 324 distance learning university students that positive comments and encouragement can be given effectively by thanking students for their contributions by name, smiling, and giving written and verbal praise on their assignments. As Ellis (2009) discusses, positive feedback has not received as much investigation as negative feedback (i.e., corrective feedback) in the field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA), but pedagogical theory values it for its provision of affective support and increased motivation in learning.

Another form of interaction that not only plays a role in building rapport but has also proven to be an essential component to second language learning is corrective feedback (cf; Ellis, 2009; Swan & Shea, 2005). As proposed by Hays (1970), the climate of the classroom depends on whether the student perceives the teacher’s communication in a defensive way or not. As such, the moments of corrective feedback offer the student the opportunity to observe empathy from the teacher who is aware that the pride and confidence of the student are at risk. A study by Swan and Shih (2005) found that in the online setting, when students may feel particularly isolated, constructive and timely feedback, among other characteristics such as self-disclosure and encouragement from the teacher, is a means by which the instructor can foster positive teacher-student rapport essential in online learning. Likewise, the way in which the teacher provides corrective feedback

can communicate esteem and patience. Hawk et al. (2002) found that empathy, respect, and patience are fundamental elements in the development of the teacher-student relationship, and they motivate the student toward a higher academic performance. Their study showed that teachers can show and build respect by maintaining a courteous attitude, putting effort and energy into their work, as well as having enthusiasm for the class, loyalty to the school, and a genuine caring for the learners.

Personal thematic discourse, the third form of interaction investigated in this study, promotes a sense of connection that develops through sharing personal and authentic experiences, including by the teacher (Henry et al., 2018; Blattner et al., 2012). Self-disclosure, that is, personal discourse, has also been shown to build rapport by means of communicating a personal investment in the relationship (Cayanus et al., 2009). As González-Lloret (2020) explains, classroom community can be strengthened through the disclosure of personal information during classroom activities such as likes, dislikes, fears, and other details that help the students and teacher get to know each other. Additionally, Rovai (2002a) found that personal discourse can be fostered in the online classroom by putting learners into groups for informal discussions at the start of the term, as well as by assigning collaborative activities. As shown in a study by Hackman and Walker (1990), instructors can promote student participation online by asking questions, encouraging students to share, and giving personal examples. Blattner and Lomicka (2012) discuss an increased self-disclosure by students, higher motivation and a more positive classroom environment due to teacher self-disclosure via Facebook®. As found in studies by Zhang et al. (2009), and Cayanus et al. (2009), there are various advantages of self-disclosure by the teacher such as the positive correlation between the teacher-student relationship, motivation and academic performance. In the case of this study, the term thematic has been added to personal discourse to signify the inclusion of personal experiences in line with the topic being studied in the classroom.

Based on these studies that focus on the teacherstudent relationship, interaction, and academic performance, further investigation into the forms of interaction that aid in the development of positive rapport as well as differences between the FtoF and online classroom are essential in order for teachers to establish and maintain the interaction necessary to promote positive relationships in both the FtoF and online environments.

Method

This qualitative study examines students’ perceptions of the differences and similarities between the online and FtoF FL classroom regarding the development of rapport with the teacher and peers, as well as differences in teacher feedback after the sudden transition from the FtoF to the online classroom due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. A qualitative analysis was also conducted on the impact of the three forms of interaction investigated in this study: positive comments, corrective feedback, and personal thematic discourse on the teacher-student and student-student relationship from the point of view of the students. To do this, approval was sought from the irb to conduct the study. Written consent to participate was given by the students before completing the questionnaire (see Appendix).

Participants

The participants of this study were university students in beginner-level Spanish as a Foreign Language classes at a university in Hawai’i between the ages of 18 and 21 years old. The study included six intact classes of the same level and curriculum with six different teachers. Each class lasted 50 minutes, three days a week. The classes adopted a communicative and task-based pedagogical approach (Long, 1985), and followed a task-based textbook called Gente: A Task-Based

Approach to Learning Spanish. Classroom activities intended to engage students in goal-oriented and relevant tasks with an emphasis on communication and language use, while also practicing listening, writing and reading. For the first half of the semester, the classes were held face-to-face, while the second half, due to the emergence of COVID-19, was conducted online using Zoom for synchronous meetings. With the shift to the online setting, more Web 2.0 technologies were implemented in order to allow for a continuation of relevant and meaningful interactive and collaborative tasks.

Data Collection

In order to collect data on the students’ perceptions of the quality of their relationships as a result of the three forms of teacher interaction, as well as being in the FtoF versus online classroom, the students completed an anonymous questionnaire via Google Forms with closed and open-ended questions (See Appendix). Five to six minutes were needed to complete the questionnaire. It was constructed by the author of this study based on previous research such as by Dörnyei (2003), Swan and Shih (2005), Sher (2009), Rovai (2002a, 2002b), and Rovai et al.’s Sense of Classroom Community Index (SCCI) (2001).

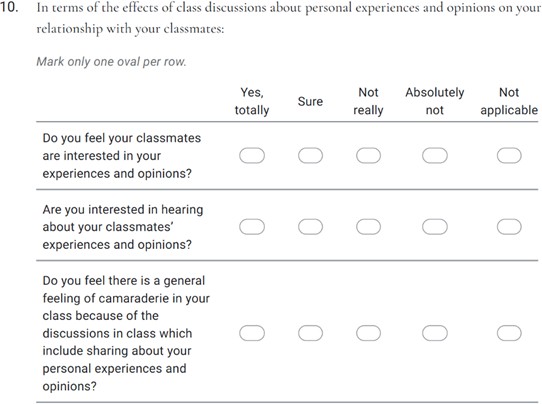

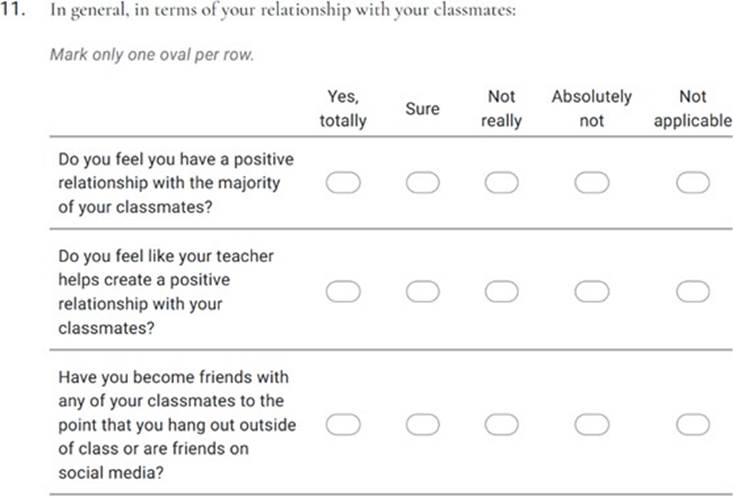

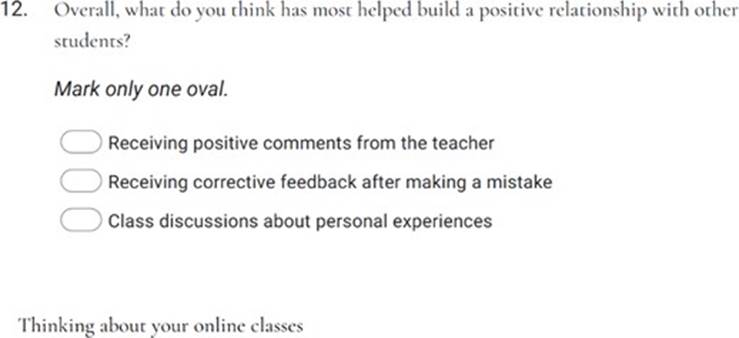

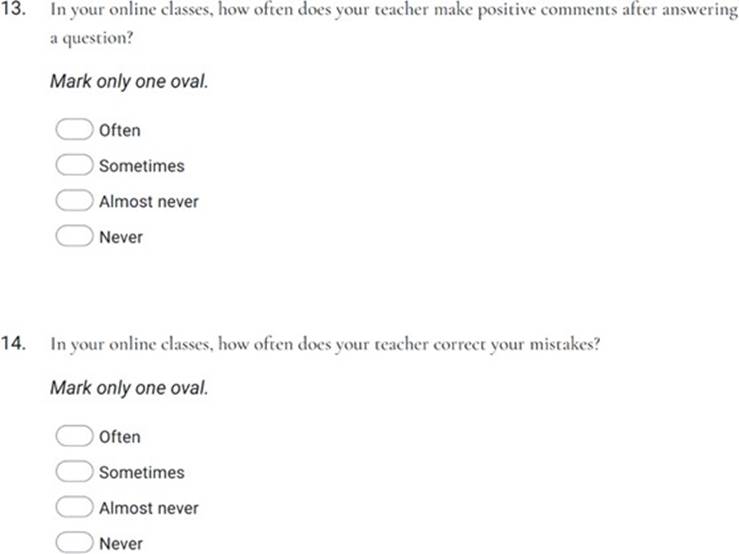

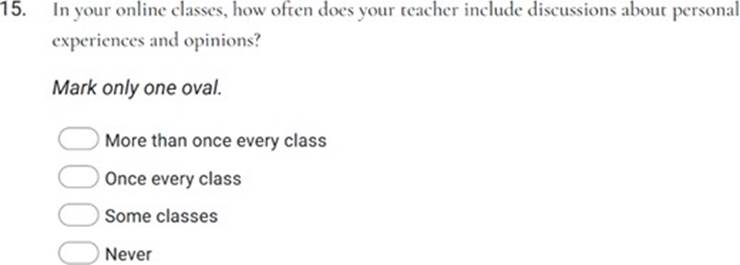

The questionnaire has three parts. The first part of 13 closed-ended questions focused on the students’ perceptions of their relationship with their teacher as a result of their teacher’s use of the three forms of interaction in the FtoF classroom. The second part, also consisting of 13 closed-ended questions, examined the students’ perceptions of their relationship with their classmates while considering their teacher’s use of the three forms of interaction in the FtoF classroom. Lastly, the third part allowed students to compare the development of their relationships with their teacher and classmates online versus FtoF as well as any differences in their teacher’s use of feedback in these two conditions. It includes six closed-ended questions and three open-ended questions.

Data Analysis

The data of this study was analyzed qualitatively, with the implementation of thematic analysis for the open-ended questions of Part 3 of the questionnaire. As data could potentially vary according to the teacher, the responses of the students were firstly analyzed separately per class (i.e., per teacher). Since it was clear that there were no differences between the groups, data was aggregated. Twelve of the thirteen questions in both Parts 1 and 2 regarding the forms of interaction were analyzed according to the value each question received based on the students’ responses of Yes, totally; Sure; Not really; and Absolutely not. On the questionnaire, the student response of Yes, totally, was equivalent to the interaction having a very positive impact, and it was assigned 6 points; Sure, or a somewhat positive impact, was assigned 4 points; Not really, or no significant positive impact, was assigned 2 points; and Absolutely not, definitely no positive impact, was assigned 0 points. After a value was ascertained per form of interaction, the impact of the three forms could be observed per class.

Lastly, a thematic analysis was done of the three open-ended questions of Part 3 which explored the students’ perceptions of online versus FtoF classes on building positive relationships with their teacher and classmates as well as the differences they noticed in feedback online and FtoF. Further analysis was made by comparing the prevalent themes with the responses to the closedended questions of Part 3 which asked directly which setting, online or FtoF, was preferred regarding the development of the teacher-student and student-student relationship. As with Parts 1 and 2, data was analyzed separately and then aggregated as it was clear that there were no differences between the groups.

Results

Due to the focus of this special issue on the role of technology in language teaching and learning amid the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the results presented below will commence with a focus on the similarities and differences between the FtoF and online classroom, as investigated in Part 3 of the questionnaire, followed by the impact of the three forms of interaction on these relationships in the FtoF classroom.

Online versus FtoF Classes and the TeacherStudent Relationship

Differences between synchronous online and FtoF classes in building a positive teacher-student and student-student relationship, as well as differences in teacher feedback, were explored in the final part of the student questionnaire. First, students were asked to compare the teacher-student relationship online versus FtoF. When asked the open-ended question about why they thought online or face-to-face classes were better for building a positive relationship with their teacher, the student responses were in favor of the FtoF instructional setting. The most common response stated that FtoF provided a more personal experience (26 % of the students; 14 of the 56 students). This was followed by a better ability to connect in a FtoF classroom as said by 7 of the students (13 %). It should be noted that out of the 13 % of students who said they experienced a greater connection with their teacher FtoF, almost half of these also described this connection as being personal, displaying a possible overlap between the two responses of a more personal experience and ability to connect. Other shared responses included better communication (11 % of the students), better interaction (9 %) and easier to ask questions (9 %). Additionally, four students (7 %) stated that FtoF classes felt more real or genuine, and three students (5 %) mentioned FtoF classes made it easier to stay motivated. Lastly, two students (3 %) stated that they were more likely to attend office hours and discuss issues with their teacher after class when FtoF. As can be seen, there are various factors that take place in the FtoF classroom which can be taken into consideration when planning for and conducting a synchronous online class.

Regarding the closed-ended question about the teacher-student relationship, when asked whether they thought online or face-to-face classes were better for building a positive relationship with their teacher, the students in five of the six classes unanimously answered in favor of FtoF. In the sixth class, two out of fourteen students chose online classes (Figure 1). As can be seen, the students shared an overwhelming preference for the FtoF classroom in terms of developing teacherstudent rapport, as discussed above. Subsequently, in response to the first research question of this study, whether FtoF or online synchronous classes have a greater impact on the development of a positive teacher-student relationship, FtoF classes were perceived by the students to have the greatest impact on the development of a positive teacherstudent relationship.

Online versus FtoF Classes and the Student-Student Relationship

Students were also asked to compare the impact of online versus FtoF classes on the development of their relationships with their peers. When asked the open-ended question about why they thought online or face-to-face classes were better for building a positive relationship with their classmates, similarities and differences could be seen with the results discussed above regarding the FtoF classroom and the teacher-student relationship. The most common response to this question in support of the FtoF instructional setting was “interaction” as answered by 20 of the 52 students (38 %) to answer the question. This contrasts with the 9 % who mentioned this attribute regarding the teacher-student relationship in the FtoF classroom. On the other hand, common responses regarding rapport building with peers, in line with building a positive relationship with the teacher, expressed that there was a more personal experience in the FtoF classroom, as said by 7 students (13 %), better connection (13 %), and better communication (9 %). More clarification would be needed, but there could be overlap among the answers of interaction and communication as well as between a personal experience and better connection.

When examining the impact of the FtoF and online classroom through the close-ended question regarding whether they thought online classes or face-to-face classes were better for building a positive relationship with their classmates, three of the six classes unanimously chose FtoF classes. In two of the other classes, 2 out of the 8 students chose online classes, while in the last class, 4 out of the 10 students chose online classes. Overall, 48 out of the 56 students chose FtoF classes for developing a positive student-student relationship (Figure 2). These results provide insight into the second research question, which was “In terms of face-toface and online synchronous classes, which has a greater impact on the development of a positive student-student relationship?” As can be seen, the majority of students elected FtoF classes as having a greater impact on building a positive relationship with their classmates. Although to a slightly lesser degree than the 54 students that preferred the FtoF classroom for developing the teacher-student relationship, the need to bring qualities from FtoF to online is again apparent.

Online versus FtoF Feedback

As two of the types of interaction discussed in this study are forms of feedback (positive comments and corrective feedback), differences between online and FtoF feedback were explored with one open-ended and one closed-ended question.

In order to examine the attributes of feedback online and FtoF as seen by the students, they were asked how they thought feedback was the same or different in the online and face-to-face Spanish class. In response, more than half of the students said they are the same (52 % of the students). Although preference for one medium or the other was not part of the question, 48 % of the students shared that they preferred face-to-face feedback. 12 % of this latter group stated the reason was the ease of asking questions when face-to-face. 7 % stated that face-to-face feedback is more personal. Other answers included various difficulties of online learning in general. Students who felt that face-to-face and online context were the same referred to the same amount of feedback, same content, and same learning from the feedback.

In terms of the effectiveness of online versus FtoF feedback, students were asked a closed-ended question regarding whether they thought getting feedback in online language classes was more, the same, or less effective than in face-to-face classes. Only 5 of the 56 students (9 %) said more effective, while 22 (39 %) said less effective. That said, a little over half of the students (52 %) said it was as effective (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Student Answers to the Question: Do You Think Getting Feedback in Online Language Classes is More, the Same, or Less Effective Than in Face-to-Face Classes? Note. Total number of students was 56.

This raises the third research question regarding the students’ perception of differences between synchronous online and FtoF feedback given by the teacher: How does feedback differ from the face-to-face to online classroom? As can be seen, there is a mixed perception of not only the effectiveness of feedback online versus FtoF, but also regarding the similarities and differences between the two. Nonetheless, although 52 % of the students stated there were no significant differences, it is noteworthy that almost half of the participants (48 %) stated that they preferred FtoF feedback and 39 % stated that FtoF feedback is more effective. As the students’ answers varied greatly regarding the differences, further investigation into the preferred qualities of feedback in the FtoF classroom would be beneficial in order to be able to implement them as much as possible in the online setting.

The Teacher-Student and Student-Student Relationship in the FtoF Classroom

The following section presents the results of the thirteen closed-ended questions of Parts 1 and 2 of the student questionnaire regarding the impact of the three forms of interaction: positive comments, corrective feedback and personal thematic discourse on the teacher-student and student-student relationship in the FtoF classroom.

In accordance with previous studies (Swan, 2003; Ellis, 2013; Pacansky-Brock et al., 2020), the results revealed that among the six classes all three forms of interaction have a positive impact on the teacher-student and student-student relationship in the FtoF classroom. That said, certain forms of interaction were perceived to have a greater impact on rapport than others. First, when asked the closed-ended question regarding which of the three forms of interaction most helped build a positive relationship with their teacher in the FtoF classroom, 25 out of 56 students chose receiving positive comments (44.6 %), followed closely by 24 students who chose corrective feedback (42.9 %) and 7 who chose personal thematic discourse (12.5 %; see Figure 4). This raises the fourth research question: Of the three forms of interaction from the teacher examined in this study (positive comments, corrective feedback, and personal thematic discourse), which are the most effective in the development of a positive teacher-student relationship? As can be seen, the results reveal that positive comments and corrective feedback were chosen by the students to be the most effective in the development of this relationship. It should be noted, however, that the small number of students to choose personal thematic discourse (12.5 %) may reflect a perceived role of the teacher as one who gives feedback, and not one who engages in personal thematic discourse with the class. It may also be due to the lack of clarity in the questionnaire that personal thematic discourse includes the self-disclosure of personal experiences and opinions by the teacher.

Figure 4 Combined Class Answers to the Question: Overall, What Do You think Has Helped Build a Positive Relationship Between You and the Teacher Most? Note. This figure shows the total number of students.

In contrast to the impact of the three forms of interaction on the development of the teacher-student relationship in the FtoF classroom, the majority of students did not pick positive comments or corrective feedback as having the greatest impact on their relationship with their peers although positive comments and corrective feedback were indeed still chosen by some. When asked the closed-ended question regarding what they thought had most helped build a positive relationship with their classmates, 35 out of 56 students chose personal thematic discourse (62.5 %), followed by 14 students who chose positive comments (25 %) and 7 who chose corrective feedback (12.5 %; see Figure 5). As a result, in answer to the last research question regarding which of the three forms of interaction were most effective in the development of a positive student-student relationship, it can be seen that the majority of students share a strong preference for personal thematic discourse. That said, it is noteworthy that a quarter of the students still chose positive comments, and 12.5 % chose corrective feedback.

Note. This figure shows the total number of students.

Figure 5 Combined Class Answers to the Question: Overall, What Do You Think Has Helped Build a Positive Relationship Between You and Your Classmates Most?

The fact that positive comments were perceived as an important factor in both teacher-student and student-student rapport, yet in the case of this study, they are a form of interaction between teacher and student shows that a causal relationship may be seen between the development of the teacher-student and student-student relationships. Although only 12.5 % of the students chose corrective feedback, this is also an interaction directly linked to the teacher within the context of the questionnaire, again showing a possible causal relationship between the teacher-student and student-student relationships. As such, the need to promote these three forms of interaction in the second language classroom is not only important for teacher and student rapport, but rapport among peers, as well.

Lastly, the initial twelve closed-ended questions of Parts 1 and 2 of the questionnaire examined the impact of each of the three forms of interaction separately on teacher-student and student-student rapport in the FtoF classroom prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Regarding the teacher-student relationship of Part 1, on a scale of 0 to 6, the responses to each set of four questions were between 4.83 (4 representing a somewhat positive impact) and 6 (representing a very positive impact). As such, the three different types of interaction were perceived very similarly by all students regardless of teacher (see Figure 6), and they were also all regarded positive comments; 5.55 for corrective feedback; and 4.41 for personal thematic discourse).

Figure 6 Student Responses to the 12 Questions of the Impact of the Three Forms of Interaction on the TeacherStudent Relationship. Note. 6 = Very positive; 4 = Somewhat positive; 2 = Neutral; 0 = Absolutely not positive

Similarly, the twelve closed-ended questions of Part 2 regarding the student-student relationship show that all three interactions were perceived positively as a whole among each class, regardless of teacher (see Figure 7), and they were also all regarded as important (5.56 average for positive comments; 5.23 for corrective feedback; and 5.03 for personal thematic discourse).

Figure 7 Combined Answers to the 12 Questions on the Positive Impact of the Three Forms of Interaction on the Student-Student Relationship. Note. 6 = Very positive; 4 = Somewhat positive; 2 = Neutral; 0 = Absolutely not positive

As can be seen, the initial twelve closed-ended questions of both Parts 1 and 2 regarding the teacher-student and student-student relationship revealed that all three interactions were perceived positively as a whole. In fact, although teachers tend to be a variable, there did not seem to be a notable difference among the responses per class regarding the impact of each form of interaction. That said, the lack of differences in the perception of the impact of each of the three forms of interaction on teacher-student and student-student rapport may be due to the design of the questionnaire not eliciting enough granularity on the data. Additionally, it should be mentioned that these closed-ended questions were not aimed at showing which form of interaction was perceived to have the most positive impact on building rapport with the teacher and peers, but simply if it had a positive or negative impact in and of itself.

In summary, as shown in the results of this study, although all three forms of interaction have a positive impact on the development of both teacher-student and student-student rapport, the development of said relationships in the FL classroom involves an array of factors which not only vary depending on the type of relationship (i.e., teacher-student or student-student) but also between the FtoF and online settings.

Discussion

Examining the development of positive teacherstudent and student-student relationships in the online and FtoF classroom from the point of view of the students, as well as differences between online and in-person feedback, important information has been revealed about the need to bring qualities of the FtoF environment into the synchronous online setting in order to promote a more personalized and communicative space. As various studies suggest, a sense of connectedness in the online classroom is indeed valuable and possible in order to satisfy students’ desire for community and satisfaction in the course (Gallien & Oomen, 2005). Now more than ever, with the unexpected transition to the online classroom from the FtoF setting due to the emergence of COVID-19, there is a need to establish the attributes that help build positive rapport in the online classroom.

As seen in this study, the students shared an overwhelming preference for the FtoF classroom in terms of developing both teacher-student and student-student rapport. Although a preference for the FtoF classroom at the time of the questionnaire was clear and shared by students taught by six different teachers, it should be noted that the students had only completed four weeks of online classes after an unexpected transition due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, their responses were framed within a very unique setting. The same classes may have a different experience the following semester once both students and teachers alike have had more experience navigating the synchronous online space and teachers and institutions have had time to develop materials appropriate for online teaching and opportunities for authentic interaction. Nonetheless, the student responses reveal important information on the valued qualities of the FtoF classroom such as a greater ability to connect, a more personal setting, a greater ease in asking questions and receiving feedback, and more interaction, which can now be fostered in the online setting prevalent in this time of pandemic.

To start, looking at the three interactions investigated in this study in the FtoF classroom, this study can affirm that all three forms of interaction have a positive impact on the teacher-student and student-student relationship as found in previous studies (Swan & Shih, 2005; Sher, 2009; Blattner et al., 2012). It was unexpected, however, to see that corrective feedback was chosen by almost as many students that chose positive comments when asked which form of interaction they found to have the greatest impact on building a positive relationship with the teacher. Although corrective feedback has been shown to be a fundamental element in second language learning (Ellis, 2009), it was not anticipated to be perceived as positively by the students in terms of relationship building. That said, receiving personalized meaningful feedback is indeed a means by which the teacher can show their support and connect with the students (Pacansky-Brock et al., 2020). As a result of these findings, further investigation into the strategies implemented for giving corrective feedback, as well as the other two forms of interaction that students find to be the most effective on building rapport with both teacher and peers would be beneficial in order to better understand which methods best foster these relationships in the FtoF and online instructional setting.

On the other hand, the fact that almost half of the students chose positive comments as having the greatest impact on building a positive relationship with their teacher is not surprising. As Ellis (2009) explains, positive feedback provides affective support to the student which in turn motivates the student to continue learning. In fact, it is not only an important way to foster positive attitudes but is as important as, if not more than, negative feedback in the classroom (Ellis, 2013). As Pacansky-Brock et al., (2020) describe, the development of the teacher-student relationship through forms such as validation is at the heart of connecting students with each other and increasing student engagement and rigor. Likewise, in the results of this study, the value of positive comments, despite being a form of interaction between teacher and student, extended to rapport building among peers, demonstrating a possible causal relationship between the teacher-student and student-student relationship. As such, positive comments are indeed an essential interaction in building rapport in the FL classroom as they not only improve the teacher-student relationship but the student-student one as well.

Regarding the third form of interaction, personal thematic discourse, the fact that it was the most widely elected interaction by the students for its impact on building rapport with peers corresponds with previous studies which have shown that strong connections are built through personal discourse (Gallien & Oomen, 2005; Cayanus et al., 2009; González-Lloret, 2020). Consequently, it was surprising to be the interaction least chosen by the students regarding building rapport with their teacher. This could be due to the perception of the teacher as not being a participant in classroom discourse involving the self-disclosure of personal experiences. Future studies involving a focus on personal thematic discourse between students and teacher through activities in which the teacher explicitly shares their experiences (such as with Web 2.0 tools as discussed in further detail below) would allow for more insight into the impact of this form of interaction on teacher-student rapport. In fact, the use of technologies that promote meaningful interaction may not only aid in developing a sense of community (González-Lloret, 2020), but provide a bridge that allows for the personal connection and social presence valued in the in-person classroom to be promoted online (Lomicka, 2020).

As discussed, the presence of the favorable characteristics found in the FtoF classroom that help build rapport can now be fostered in the online setting with today’s advances in technology-mediated activities and greater opportunities for teacher-student and student-student interaction. More and more research has shown the success and benefits of authentic interaction in the online classroom (Woods et al., 2004). In fact, a study by Rovai (2002a), which compared the sense of classroom community experienced by 326 participants in FtoF and asynchronous online courses, found that the feelings of disconnectedness and isolation often associated with online learning were more often due to the course pedagogy and/ or design than the online setting. Accordingly, Rovai’s study suggests that at least the same level of community can be built in the online classroom as in the FtoF one. Likewise, various studies have revealed that instructors’ immediacy behaviors, that is, the interactions that minimize the feeling of distance between the students and teacher (i.e., encouragement, praising, individualized feedback, using humor, self-disclosure, etc.), promote this closeness and increase student satisfaction in the online classroom (Gallien & Oomen, 2005; Swan & Shea, 2005a). Indeed, these are some of the attributes that students mentioned enjoying in the FtoF classroom in this study. Fortunately, these are skills that teachers can implement online with the aid of certain technologies, as discussed in Pedagogic Implications below.

Pedagogical Implications

The implementation of the forms of interaction which improve the teacher-student and studentstudent relationship, is of great importance due to their role in motivation and performance in learning a FL. These forms of interaction along with the other attributes presented in this study, such as a more personal setting and a greater connection face-to-face, need to be converted as much as possible to fit the synchronous online classroom. Accordingly, a discussion of available techniques will follow, some of which would also be useful additions to the FtoF classroom.

There are numerous strategies to add occasions for interaction and connection in both the FtoF and online classroom. Some textbooks based on the communicative and/or task-based methods already present activities that could be a starting point and transferred to the synchronous online classroom with the use of breakout rooms in Zoom and collaborative writing in Google Docs. In fact, studies have shown that students can interact in breakout rooms in a way that may actually be more comfortable for them than face-to-face (Debrock et al., 2020). Furthermore, having longer and more frequent pair and small group activities in breakout rooms as well as FtoF, creates more opportunities for the teacher to give feedback and to promote a more personal environment.

In terms of Google Docs, supplementary documents in line with the textbook can be created that permit the sharing of personal experiences and goals with collaborative writing in live time by the students. During such activities, the teacher can give immediate personalized feedback, both positive and corrective, verbal and written, along with comments and additional questions concerning the students’ interests. As found in a study by Sher (2009) conducted across 30 sections of online university learning programs, treating students as individuals and promoting an environment that fosters the sharing of learning experiences, a sense of community, teamwork, and interaction are valuable factors in online learning.

Beyond the possibility of self-disclosure involved in collaborative writing activities, the addition of comments and questions by the teacher can promote a sense of connection and community. It is the small actions, after all, that also play a part in developing positive rapport. For example, by arriving before and staying a little after a synchronous online class, a teacher can mimic the aspect of a more personal setting as found in the FtoF classroom. Similarly, by actively promoting office hours online, students’ desire for a greater ease in asking questions and receiving more personal feedback is addressed to a degree (DeBrock et al., 2020). Lastly, the use of icebreakers, even if not based on the textbook topic, allow students to get to know each other better and build a sense of community (González-Lloret, 2020).

Interaction among students can also occur during and outside of class by means of accessing everyday tools offered by the Internet in order to complete tasks that are relevant to the students’ lives. Such tools, as discussed below, can be completed in small groups or pairs in breakout rooms during synchronous online classes, as well as asynchronously. One such tool is Yelp, which allows students to complete meaningful tasks concerning restaurants or other shops of their choosing. Tools such as Google Earth and Google Maps allow for interaction concerning directions and searches of places of interest in a fun and relevant manner (González-Lloret, 2020). While using these tools to work collaboratively, the teacher can give personalized feedback, both positive and corrective, in breakout rooms or on the students’ Google Docs if used, as well as afterward with the class as a whole.

Activities including more self-disclosure and personal thematic discourse could be completed using social networks such as Facebook or Instagram, or other interactive platforms such as Padlet and FLipgrid. As Blattner and Lomicka (2012) explain, the amount of face-to-face interaction that students get in class is limited, whereas social networking sites allow students to build rapport with their peers and their teacher in a way that may be even more motivating and personal. Padlet may be used to reflect on and share personal experiences and interests as pertains to the classroom topic. It is an interactive web-based board upon which students can respond to the teacher and other students in a written format, create topics, and upload pictures. As described by Maceira et al. (2017), the manner in which Padlet can be used to reflect on one’s daily life and comment on the reflections of others is similar to the authentic responses to user-generated content such as on Facebook.

Lastly, another user-friendly and interactive tool is FLipgrid, a tool to be used asynchronously. FLipgrid is a website that allows teachers to create topics or tasks on which a shared, collaborative board of students’ work (i.e., videos) is posted and available for video discussion and feedback. In terms of community building, being able to not only see and hear classmate’s output when interacting through video messages but also have all the videos on one wall allows students to connect and get to know each other. In fact, within a community, even one that is in a digital space, students can express their identity through their stories of their friends and family, what they choose to wear in the video, their background, and how they respond to their classmates (Sickel, 2020).

As can be seen, the online classroom has opened up more opportunities to utilize the Internet to not only build language competencies in meaningful ways but to create spaces within and outside of the class for students to interact, get to know each other, and allow the teacher to give the feedback essential in foreign language learning and the development of positive teacher-student and student-student rapport.

Conclusions

This study reveals the importance of feedback from the teacher in the teacher-student relationship in the form of both corrective feedback and positive comments as well as the importance of positive comments and personal thematic discourse on the student-student relationship. Not only this, but the need to bring qualities from the FtoF classroom to the online setting, such as a sense of a more personal experience, ability to connect, ease in asking questions and receiving feedback, and greater interaction has been presented along with ways to do so. Due to the fact that the development of these relationships is perceived to be greater in the FtoF classroom by the students, exploring the attributes of the abovementioned characteristics, as well as how to further bring the qualities of positive comments, corrective feedback, and personal thematic discourse into the synchronous online classroom is essential.

In spite of the factors that limit this study such as the interpretive nature of the data of the questionnaire and the lack of granularity as seen in the data, some qualities that students value in the FtoF classroom have still been revealed, as well as the need to foster said factors in the online classroom. Now, with the rise in online classes as a result of COVID-19, there is an even greater need for studies to not only take place in the FtoF classroom but also in the online one, as well. Such future studies would benefit from being performed in online courses that promote collaborative and technology-mediated learning, such as in technology-mediated task-based teaching curriculums, which would allow for further insight into the creation of a more personal, interactive and collaborative space that harnesses the potential of technology and language use. In conclusion, with today’s technology and knowledge of collaborative online activities, the emotional element found in in-person exchanges may now take place in an online environment. As discussed by DeBrock et al. (2020), it is indeed possible to bring the “human element” to online learning.