Introduction

Power struggles have always been present in human history, and in the last few years, thanks to the insertion of decolonial theory in the educational scenario, and more explicitly, in the English language teaching field (ELT), scholars have begun to question the Status quo in multiple manners to detach from hegemonic influences that have been permeating this area. For instance, in Latin America previous scholarship on native-centered models for students to achieve a native-like pronunciation has started to turn to areas that aim to acknowledge and incorporate marginalized perspectives and cosmogonies. Thereby, this has led to a more conscious theorization of the field, making it possible to hold that, within Colombian ELT and other countries of the global south, the decolonial project is gaining force.

In general terms, the main intention of the decolonial turn in ELT is to detach from phenomena that have been affecting the field for a long time. Macías (2010) names three of them: McDonaldization (Ritzer, 2008), Americanization (Phillipson & Skutnabb-Kangas, 2002), and linguistic imperialism (Canagarajah, 1999, Phillipson, 1992). These phenomena have not only promoted erroneous views on bilingualism. Beyond this, they have boosted an agenda of hegemonization of knowledge, power, and being. Because of this, individual identities and cosmogonies appear to have been influenced in order to fit into the modern marketizing-knowledge-making system where only epistemological perspectives coming from the global north seem to be valid (Castañeda-Peña, 2021; Núñez-Pardo, 2018, 2020).

Still, even if the previous aspects have been influenced by the foregoing hegemony, discursive practices, or discourse, as it is most commonly referred to, appear to have been considerably impacted. According to Escobar (2013) and Guerrero (2008, 2009a, 2009b) discourse, especially that implemented within the framework of Colombian language policy making, seems to have been manipulated to maintain unbalanced power dynamics in society. Valencia (2013) maintains that this has not only occurred as a manner to keep unbalanced power relationships among the Colombian population. Instead, this author contends that this has happened because of the desire that those in power have to continue implementing “policies like the NPB, and other neoliberal reforms” (Valencia, 2013, p. 38) that ultimately allow foreign intervention that favor a very small part of the population: elite communities that have been historically privileged.

Given the importance that discourse has for society and for Colombian ELT in general, this qualitative research study aimed at examining prevailing hegemonic discourses in ELT while also exploring counter-hegemonic discourses that have taken place in said field. This is necessary because research studies revolving around the research interest in question are scarce, even though a critical view on areas such as bilingualism (Guerrero, 2008; Mejía, 2006), the role of culture in language education (Gómez-Rodríguez, 2015), the intersection between gender affiliation and identity (Castañeda-Peña, 2021; Ubaque-Casallas and Castañeda-Peña, 2020b; Viáfara, 2016), materials design (Núñez Pardo & Téllez, 2009), and critical language policy (Correa & Usma, 2013; Escobar, 2013; Guerrero, 2008) has been growing.

Overall, this study was informed by critical literacy (CL) and critical discourse analysis (CDA). Combining principles of these approaches was paramount for the development of this research as these allowed for analyzing and unveiling the hegemonic discourses/influences that still take place within the ELT field in the country. Plus, Freire’s (1994) perspective on the notion of counter-hegemonic has helped establish how much of the national scholarly literature is resisting. Both approaches shed light on how ELT professors, researchers, and Colombian schools of education have understood the importance of questioning the colonial system (Maldonado, 2006; Mignolo, 2010; Walsh, 2013) and making our voices be heard, acknowledged, and respected.

Before proceeding, yet, it is worth bringing up this quote by Foucault (1979): “where there is power, there is resistance” (p. 95). As for the ELT field, this means that although it is observable that hegemonic influences have permeated it, there exist instances of counter-hegemony in which scholars have been acknowledging and highlighting epistemologies and identity markers/affiliations that have been suppressed and subalternized. Considering these aspects, it is possible to hold that decoloniality is not only an agenda that seeks emancipation and liberation of oppression. Besides that, it is an attitude and lifestyle for which we have to fight and live for (Maldonado, 2006; Mignolo, 2010; Walsh, 2013) to raise a more conscious and critical reflexive view of towards the field and life in general.

Theoretical Framework

This section presents a review of the two guiding constructs of the study: the notions of hegemony and counter-hegemony and othering/ otherness and towards the recognition of alternative discourses in Colombian ELT: The representation of others as equal ones. These constructs were fundamental for the development of this study as hegemony has been permeating different areas of society ranging from politics to culture, and even education. ELT is no exception to this rule, and by understanding how it has influenced this field, the academic community in general will have a clear understanding of how to face these harmful dynamics.

The Notions of Hegemony and Counter Hegemony

Hegemony has been theorized by multiple authors across scholarly literature. For example, H. Davis (2004) conceptualizes it as “the winning of consent in order to gain and maintain power. Consent, however, is not a fixed goal. It is a moment of power which is always contestable and that has to be constantly rewon” (p. 46). On the other hand, Weaver et al. (2016) establish that hegemony is related to the maintenance of ideologies/deeds that disempower individuals with epistemologies that differ from mainstream socio-cultural and political relations, which implies that individuals/communities who do not fit into the status quo are normally segregated. In turn, Lull (1995) refers to hegemony as asymmetrical power dynamics that occur between and among social classes. In a few words, hegemony can be conceived as the set of ideologies/agendas that “impoverish, disenfranchise, enslave, disempower, and humiliate people” (Sawyer & Norris, 2013, p. 6) to maintain unbalanced power dynamics that only benefit a small part of the population fitting in standards imposed by those in power.

As suggested above, hegemony has the capacity to position some individuals, knowledge, or actions as superior and others as inferior. In Colombia, hegemony has been especially noticeable in policy-making processes as ELT and national policy designers have been responding to interests from international entities as it is the case of the British Council (Correa & Usma, 2013; Usma-Wilches, 2009). Although it is not negative at all, as the British Council is an authority in the field of English language teaching worldwide, overlooking the specificities of the different existing communities and their corresponding epistemologies in order to impose neoliberal standards is indeed harmful. This situation has been highlighted by the aforementioned authors as they established that not all stakeholders’ viewpoints are considered at the moment of designing Colombian linguistic policies. Therefore, it is worth asserting that hegemony is a system through which individuals who do not enact privileged identity markers or affiliations are oppressed and marginalized. Consequently, their voices are silenced.

On the other hand, counter-hegemony, or decoloniality as it is also frequently denominated, refers to the array of actions that set the possibility of a deep and transformative liberation. In this sense, Carroll (2006) establishes that counter-hegemony seeks to transform society and “abolish underlying generative mechanisms of injustice” (p. 20). Moreover, it seeks to raise awareness about individuals or groups who have been oppressed throughout history; and those whose experiences and knowledge have not been completely acknowledged in society and other scenarios including education (Zembylas, 2013). Hence, beyond a political agenda, counter-hegemony also comprises a socio-academic initiative that intends to contest Westernized views on knowledge as, historically speaking, knowledge produced in Anglo-European scenarios has been regarded as the valid one.

As a result of the previous circumstances, concepts including the subaltern and knowledge otherwise have been gaining ground in the overall educational scenario because they help illustrate the positions of subjugation or superiority in which some individuals are. Regarding the specific field of ELT, counter-hegemony is exercised in new spaces for reconsidering the English language teaching profession and what it means to be an English language teacher in a country like Colombia. This is especially observable in recent ELT scholarly literature where decolonial and critical reflexive lenses have been drawn on to obtain more realistic, reflexive, and sensitive insights into the context where these take place. Therefore, it is possible to claim that concepts such as otherness and the questioning of the structures of the structure (Castañeda-Peña, 2021) are more often considered.

Othering, Otherness and Towards the Recognition of Alternative Discourses in Colombian ELT: The Representation of Others as Equal Ones

This second construct is crucial for the development of this research study since, within the context of this investigation, discourse is not merely understood as the oral exchange that individuals enact. Although this exchange is undeniably one of the principal components and manifestations of discourse, in an overall sense, this latter is made up of several structural and sociocultural subsystems that intertwine and vary depending on the context.

Unfortunately, because of the political and ideological power of the west, discourses about whiteness, native speakerism, and othering have spread around the globe. In general terms, these supremacist discourses (Ferber & Kimmer, 2000) or discourses of othering/otherness have been present in ELT and in knowledge in general as standardizing dynamics closely linked to identity, gender, values, and knowledge have been promoted by groups in power (Ferber & Kimmer, 2000).

In relation with this aspect, Dervin (2016) sustains that the main purpose of said discourses is to turn “the other into an other, thus creating a boundary between different and similar, insiders and outsiders’’ (p. 2) expanding even more the gap that exists between people from different affiliations. In short, they seek to demonize all those who are different to what has been established as socially correct.

On the contrary, alternative discourses are defined as discourses that emerged as an opposition to mainstream Euroamerican stances. According to Wang (2010), alternative discourses challenge implicit notions of racism, xenophobia, homophobia, and other ideologies that oppress a big majority. These types of discourses have the potential to acknowledge individuals that have been marginalized as some nationalities, religions, languages, identities, and even races have been demonized (Dervin, 2016).

To conclude, it is worth reaffirming that, within the context of this research study, discourse is not merely a set of linguistic units that encompass a message or that characterize certain groups present in society (Gee, 2015). Beyond that, discourse is perceived as a set of actions that have a two-fold purpose. On one hand, it may contribute to the consolidation of hegemonic agendas that disregard identity markers and affiliations that differ from those opposed by the powerful. On the other hand, it also has the potential of challenging such influences by representing others as equal ones who deserve the same recognition.

Method

This research was framed within the qualitative tradition as it aimed to explore and understand better a phenomenon that has been taking place lately in the Colombian socio-educational dimension (Flick, 2009; Saldaña, 2011; Stake, 2010). Furthermore, this investigation also followed principles of two approaches to qualitative inquiry, i.e., meta-synthesis and documentary analysis.

Overall, meta-synthesis was carried out because through this, the researcher aims to generate a comprehensive overview of a phenomenon through different studies already conducted that are treated as data (Walsh & Downe, 2005). In this light, studies giving an account of systematically examined phenomena become the principal data source. Likewise, incorporating documentary analysis expanded my research scope and developed a more profound understanding of a phenomenon that has taken place not only within the framework of empirical research but also in other documents in the Colombian context, these being academic, non-formal, or of any other type.

Data Collection

As previously stated, this study combined principles of meta-synthesis and documentary analysis as a manner to have a more solid collection of empirical research and other types of documents that would be beneficial for the analysis (Finfgeld-Connett, 2010; Lewis-Beck et al., 2004). Even though at first it was also my intention to incorporate in the analysis other sources like videos, images, and interviews, the research focused on written documents such as empirical and conceptual articles and language policies. This was because these are the most common sources for disseminating knowledge/information concerning Colombian ELT.

Data collection consisted of two different moments. In the first stage, research articles published in five Colombian specialized ELT journals were collected. For this, specific terms such as indigenous, decolonial, subaltern, and counter-hegemony in ELT were searched at the journals’ websites. This decision was made considering that these descriptors are highly associated with the field of critical applied linguistic and decolonial stances (Tajeddin, 2021). Secondly, official documents coming from governmental entities began to be gathered, particularly, documents published by the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN). The general requisite in this stage was that the documents must have been oriented toward English language teaching and learning. Hence, here language policies became my main source of data.

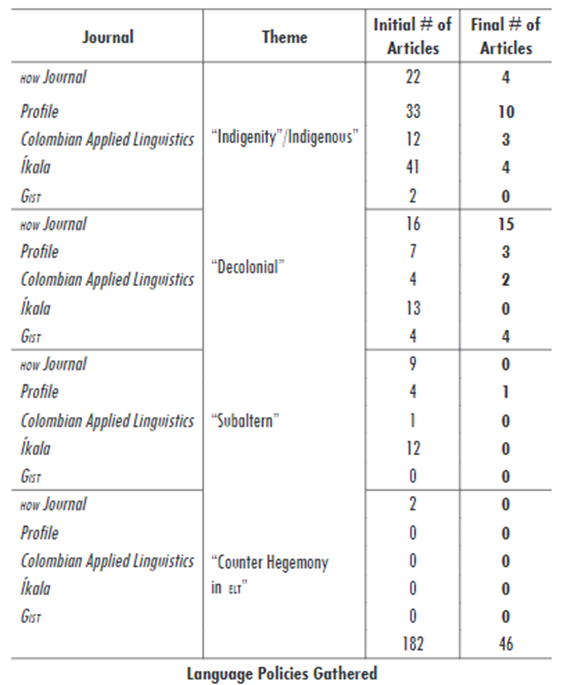

In the beginning, 182 articles were collected as they referred to indigeneity/indigenous epistemologies and knowledge (110), decoloniality (44), the subaltern (26), and counter-hegemony in ELT (two). Also, three official documents on language policies were gathered. However, some of these texts only made a general allusion to few terms or did not address a profound discussion of the same. When that occurred, I discarded said documents. It is worth remarking that another criteria I settled for gathering the articles was that they should not contain more than one of the terms established to do my search. Thus, after another review, the original number of documents to analyze was reduced as observed in Table 1.

Data Analysis and Findings

Since this study aimed at examining the types of hegemonic discourses that have prevailed in Colombian ELT while also displaying alternative discourses through which Colombian scholars within the field have been resisting such an influence, it became necessary to combine principles of CDA and CL. It is paramount to point out that, whereas CDA and CL are characterized by a large number of characteristics, for the development of this study, and following the perspective of Amoussou and Allagbe (2018), I drew on the principles of: (a)uncovering, revealing, or disclosing, (b)sustaining an overall perspective of solidarity with dominated groups, and (c) presenting an oppositional stance against the powerful for CDA on the principles of criticality and taking action for social transformation (Chapetón-Castro, 2005; Comber 2012, 2014; Moje, 2000) for cl. As a result, this action allowed analyzing more in-depth the existing relationship between the types of hegemonic discourses that have permeated ELT, the power dynamics behind these (Fairclough, 2001, 2013; Kress, 1990; Rogers, 2011), and the discourses of counter hegemony that have taken place.

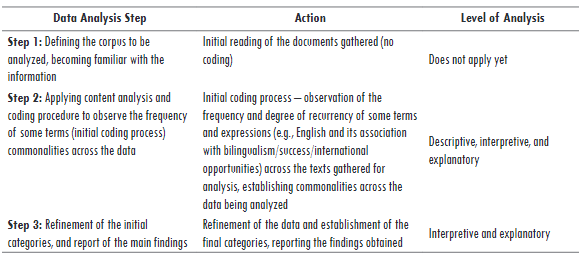

Yet, as CDA is concerned with the types of discourses and ideologies that legitimize power, as an approach, it offers a wide myriad of analytical tools to analyze the just mentioned elements. Thus, the analysis of data followed Cukier et al.’s (2009) analytical framework which consists of three steps: (1) defining the corpus to be analyzed, (2) applying content analysis and coding procedure to observe the frequency of some terms and phrases, and (3) reading and interpreting the empirical observation (See Table 2). These procedures aligned with the ones Guerrero (2008) adapted in her critical discourse study, i.e., Fairclough’s (2001) three levels of analysis. In this vein, my research accounted for (a) a descriptive stage (a linguistic analysis), (b) an interpretative analysis (analysis of a text vis-a-vis other texts), and (c) an explanatory stage, which, according to Guerrero (2008) “brings together the formal features of the text and combines it with the analyst’s own set of beliefs, assumptions, experiences and background to unveil the meaning of the texts” (p. 30).

Table 2 illustrates the data analysis process carried out.

All in all, combining these two fields of knowledge led to becoming aware of the fact that only certain agents and actors have been dictating what should be taught and how it should be done (Bishop, 2014; Dharamshi, 2018; Mora, 2014). However, and more importantly, it also allowed for acknowledging other viewpoints/voices that have been taking place within the ELT field in the last few years. In the following section I present the overall findings obtained from the implementation of this analysis.

Results

In this section the main findings obtained from the analysis of the data are presented. In general, two categories emerged. These categories were not only essential for establishing how hegemony has been acting in Colombian ELT. Beyond this, this action was vital to also showcase stances of counter hegemony where ELT scholars have been resisting such an influence.

Top-Down Decontextualized Discourses about Bilingualism, Identity, and Native Speakerism

One of the initial findings obtained from the study aligns with what other authors (Correa & Usma, 2013; Escobar, 2013; Guerrero, 2008) have already manifested: in Colombia, a large number of official linguistic documents have employed neoliberal discourses to contribute to the spread of an erroneous view on bilingualism, identity, and native speakerism.

Concerning the field of bilingualism, Mejía (2006) asserts that, in our country, “there is a tendency to focus on English-Spanish bilingualism at the expense of bilingualism in other foreign languages, or in indigenous languages” (p. 152) and other dimensions within this area have been disregarded. According to this author, it is necessary, therefore, to assume a more critical position in the ELT field. This is because it seems that, for a long time, Colombian English educators have mainly enacted a passive technician identity (Kumaravadivelu, 2003), i.e., teaching a language only for communicative purposes. Even though this situation is not totally negative, it is harmful in the sense that not incorporating principles of critical theory/pedagogy in the teaching of languages may lead to what is known as objectifying (Reagan, 2004) and instrumentalizing (Kumaravadivelu, 2003) perspectives. Consequently, wrong perceptions of language teaching may be developed.

A case in point is how the connotation of bilingualism and its implications have been influenced due to official documents. In this sense, the Colombian National Bilingualism Plan: 2004 - 2019 asserts that “Bilingualism [is] improving communicative skills in English as a foreign language in all educational sectors” (MEN, 2004, p. 4, own translation). The foregoing excerpt shows that English is favored over other foreign/indigenous languages. This is also evident in the following fragment from the text Basic Standards of Competence in Foreign Languages: English:

In the Colombian context and for this proposal in specific, English entails the status of a foreign language. Given its importance as a universal language, the Ministry of Education has established within its policies the goal of improving the quality of the teaching of English, allowing better levels of performance in this language. Thus, it is intended that when students graduate from the school system, they should have achieved at least a B1 English proficiency level (pre-intermediate) (MEN, 2006, p. 5, own translation).

As a result of these dynamics, English in Colombia has fulfilled what Mahboob (2011) regards as a gatekeeping condition. According to Mahboob, this gatekeeping condition excludes individuals who can-not afford to pay for better education in terms of English. As a result, they will not have the same academic or job opportunities as those who have mastered the language. Thus, it seems that principally the most privileged communities have the resources to access better language learning materials and other linguistic opportunities such as traveling or establishing interaction with native English speakers through academic exchanges (Matsuda, 2012).

Changing the aforementioned situations requires gradually inserting “ethnographic longitudinal multi-site case studies” (Levinson et al., 2009 as cited in Correa & Usma, 2013, p. 232) in policy-making. In this manner, it will be possible to finally leave behind generalized discourses where the English-Spanish relationship is favored since “it is not the same to learn English in a cosmopolitan city like Bogotá as it is in the countryside, or in a highly touristic town like Santa Fe de Antioquia as in a farming town like Yarumal” (Correa & Usma, 2013, p. 236).

Regarding the identity dimension, findings suggest that discourses employed in language policies have also been exerting certain influences to shape Colombian individuals’ identities and fit in international standards. In this vein, people subjugate themselves to knowledge, actions, and identities promoted by powerful countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. Valencia (2013) affirms that this has occurred because influencing Colombians to accept “the government’s creation and application of policies like the NPB, and other neoliberal reforms” (p. 38) would be a simpler way to keep promoting the insertion of transnational companies that profit from our resources. In short, it would allow a gradual colonization of being.

The colonization of being consists of suppressing individuals’ identity and interests to fit into international and marketizing standards to keep a matrix of power (Mignolo, 2010). This, according to Escobar (2013), aligns with the discourses employed by men and policymakers to sell the idea that to be successful in a country like Colombia, it is necessary to master the English language. In this light, “the Ministry of Education projects English as the modern language of development and as the only language through which knowledge construction can take place, thus depicting it as the language of success” (p. 58), and as a result, local knowledge is disregarded.

When it comes to the identity of English teachers, the previous situation is also observable. Following the perspective of the national government and its language policies, the main role of teachers should be that of reproducing knowledge mechanically and unquestionably. This is suggested in the document Basic Standards of Competence in Foreign Languages: English as it only makes an allusion to the need to train teachers, but other activities, as it is the case of implementing research related initiatives and context sensitive dynamics so as to acknowledge sociocultural specifities, are not addressed. Hence, it aligns with what Guerrero (2010b) contends when she suggests that in these types of policies, English teachers tend to be invisibilized as they are not even mentioned in this overall process.

In a critical discourse analysis study on the foregoing document, Guerrero (2010b, p. 47) also concludes that one of the motivations men has for this role of teachers is that by spreading a “poor concept of teachers plus the ideology of the colonized” it will be easier to perpetuate asymmetrical power and knowledge relationships. Therefore, it becomes paramount to keep promoting a decolonial agenda within the ELT field as it has been occurring in the last few years.

Finally, the data analysis carried out also indicates that, in Colombia, native speakerism ideologies are still valid, especially in language policies made by the government and men as it seems there is no place for other varieties of the language. This is because they refer to English as a single entity 161 times across two out of the three documents and do not even consider the possibility of acknowledging the existence of Englishes, i.e., other varieties of the English language that have not necessarily developed within the context of inner-circle countries (Kachru, 1992). Additionally, it seems that the idea of mastering English as a foreign language is highly associated with the idea of globalization as a key to success (Valencia, 2013), as shown in the following lines retrieved from the document Basic Standards of Competence in Foreign Languages: English:

The National Government has the fundamental commitment of creating the conditions for Colombians to develop communication skills in another language. Having a good level of English facilitates access to job opportunities and education that help improve the quality of life. Being competent in another language is essential in the globalized world, which requires being able to communicate better, open borders, understand other contexts, appropriate knowledge, and make it circulate, understand, and make themselves understood. Enriching themselves plays a decisive role in the development of the country. Being bilingual expands the opportunities to be more competent and competitive. (MEN, 2006, p. 3, own translation)

As suggested in the previous quotations, for men and policymakers in charge of these processes, English is reduced to a single standard version, and mastering said version assures higher opportunities of success in terms of economy and “development”. Learners and teachers must adapt to the standard because of the blind attachment to inner circle traditions where standard Englishes (e.g., American and British English) are privileged over other varieties (Macias, 2010). Moreover, our exonormative/norm-dependent condition (Matsuda, 2012) is a factor that contributes to the previous situation.

Nonetheless, it is important to remark that, within the last few years in the context of applied linguistics and English language teaching, areas such as English as a lingua franca (ELF) and world Englishes have been gaining momentum. Thus, language varieties should be more considered in policy-making processes as with the global spread of English (Ceyhan-Bingöl & Özkan, 2019; Nunan, 2001; Seidlhofer, 2009) English has stopped belonging to communities coming from inner-circle countries (e.g., the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, or Australia) and now it belongs to all of us, native or non-native communities. This fact is highlighting as even communication through English within the United States and other inner circle countries has changed.

The above-mentioned argument aligns with what has been supported by Galloway and Rose (2018) and Jenkins (2015) who suggest that if principles of ELF were included in ELT and all its dimensions, a more pluralistic view of English would be spread. Accordingly, individuals would develop a global intercultural awareness, which is an open attitude towards other cultures while considering their respective sociocultural and linguistic backgrounds (Kumaravadivelu, 2003).

Alternative Discursive Practices in Colombian ELT: Resisting Hegemony within the Field

Even though the initial examination shed light on the fact that hegemonic discourses in ELT have mainly taken place within the context of language policies, a second level of analysis showed that discourses highlighting indigenous and other alternative stances are more frequent in the field nowadays. For instance, the work developed on indigenous students’ learning process within the context of a foreign language program at a Colombian university (Usma-Wilches et al. 2018) and in other English language teaching scenarios (Benavides-Jimenez & Mora-Acosta, 2019; Cuasilpud-Cachala, 2010; Escobar-Alméciga & Gómez- Lobatón, 2010; Velandia-Moncada, 2007) demonstrates that in Colombian ELT there is now a tendency to detach from notions of whiteness and Anglocentrist and Eurocentrist perspectives that validate westernized systems of knowledge construction, and instead the “glocal” (Kumaravadivelu, 2003), which is the intersection between the global and the local, is gaining force. Yet, and as suggested by Arias-Cepeda (2020) indigenous stances urgently warrant more research.

Even though it seems that indigenous communities’ experiences and overall indigeneity (Cameron et al. 2014) trajectories have been gaining ground in ELT in this country, another area of knowledge that has gained visibility as a manner to respond to the hegemonic standardizing discourses disseminated by language policies is local knowledge production and policy making. In relation with this, in the last few years, Colombian ELT scholars (Correa & Usma, 2013; Guerrero, 2010a; 2010b; Guerrero-Nieto and Quintero-Polo, 2021; Núñez-Pardo, 2020) have manifested the necessity of creating more locally sensitive policies as it seems that historically speaking, and especially in the national context, ELT/methodologies coming from Anglo speaking countries have been taken and blindly implemented. In this regard, Bonilla-Carvajal and Tejada-Sánchez (2016), Granados-Beltrán (2016), Moncada-Linares (2016), Mosquera-Cárdenas and Nieto (2018) make a series of suggestions to create more locally sensitive language policies and materials. Promoting intercultural understanding, analyzing embedded Colombian sociocultural issues, and continuously reflecting on our role as non-native English speakers in the current 21st century where society is globally interconnected are some of the aspects that require an urgent conceptualization.

Undergoing such a process and designing more locally sensitive policies and materials would be highly beneficial for the Colombian context because of many motives. However, and possibly the most significant one, is that we are a non-native community of speakers, and as such, our “Norm depending” condition has always favored the interest of transnational influences that seek to subjugate others who do not adjust to those dynamics. This stance is reaffirmed by Fandiño-Parra (2021, p. 172) who stresses that “the Colombian ELT community complies with the teaching of a powerful high market value language without much consideration of its implication in the minimization of the linguistic capital and linguistic human rights of Colombians’’ because we have accepted norms imposed by the powerful to fulfill international standards. Hence, developing a more local perspective would allow the design of more context sensitive practices.

To continue fighting back the previous influences, Fandiño-Parra (2021) draws on the work developed by Walter Mignolo (2007), Mignolo and Escobar (2013), Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel (2007), to mention a few, and proposes the implementation of a grammar of decoloniality which consists of working on three specific aspects: (a) a decolonization of power, (b) a decolonization of knowledge and (c) a decolonization of being. Here it is worth highlighting that whereas a decolonization of power is possibly the most difficult aspect to achieve because of the interests that individuals in power have, when considering the overall data analysis, it is possible to observe that a decolonization of knowledge and being has been taking place in Colombian ELT lately.

In Akena’s (2012, p. 600) view, coloniality of knowledge is related to the production of knowledge that has been “closely related to the context, class affiliation, and the social identity of the producers”. It means that even if diverse communities from around the world have different kinds of knowledge (or knowledges), legitimized communities, that is those that fit into standard models of “whiteness” and other phenomena from the same nature have had the opportunity of deciding and imposing what should be perceived as valid. This has been widely discussed in the work of national scholars including Bonilla-Mora and López-Urbina (2021), Carreño-Bolívar (2018), Castañeda-Londoño (2017), Gónzalez-Moncada (2021), Granados-Beltrán (2018), Miranda-Montenegro (2012), Ortega (2019), Mora (2021), Lucero and Castañeda-Londoño (2021), Mesa-Villa et al. (2020), Núñez-Pardo (2020), Ramos-Holguin (2021), Soto-Molina and Méndez (2020), Ubaque-Casallas and Aguirre-Garzón (2020a) as these Colombian ELT scholars have been advocating for the gradual recognition of our epistemologies and knowledge production system from our role as non-native speakers in ELT.

To be more explicit, some of the dimensions that have been gaining recognition within Colombian ELT are the study of culture in ELT, the sense of community, and overall processes regarding ELT learning and teaching methodologies. The work of other scholars like Castañeda-Londoño (2019, 2021), Estacio and Camargo-Cely (2018), Posada-Ortiz and Castañeda-Peña (2021) has also served to visibilize that Colombian ELT is not perpetuating the original hegemonic influences from the field. Therefore, it is possible to stress that in the national context, the work of the authors I have referred to until now has contributed to the development of “Knowledge democracy” as its main intention is to acknowledge “the importance of the existence of multiple epistemologies, or ways of knowing, such as organic, spiritual, and land-based systems, frameworks arising from our social movements, and the knowledge of the marginalized or excluded everywhere (Hall et al. 2017, p. 13).

Undoubtedly Colombian ELT and discursive alternatives have been gaining ground within the last few years. This action has not only permitted a progressive decolonization of knowledge, but also a decolonization of being as positions towards identity have been gradually incorporated in the field. After the data analysis it was also possible to establish that now discourses that defy heteronormativity and other imposed “modern” perspectives of identity where mainly the binary self is accepted, have been gaining traction. Bonilla-Medina et al. (2021) highlight English learners’ racial identities configuration in ELT processes. Posada-Ortiz (2022) reconciles the bridge between pre-service English language teachers’ identity and its construction in other communities. Castañeda-Peña (2021), Castañeda-Trujillo (2021), Castro-Garces (2022), Ubaque-Casallas (2021a, 2021b), Ubaque-Casallas and Castañeda-Peña (2020b) propose examining more frequently ELT teachers’ identity because as J. S. Davis (2011) suggests, who we are inside and outside the classroom context matters, and of course, we are constantly changing. All in all, the previous analysis indicates that while hegemonic discourses, especially those coming from the men prevail, discourses highlighting alternative stances that acknowledge the other as an equal one have been gaining importance in the field of English language teaching in the Colombian context.

Discussion and Conclusions

Beyond establishing an overview of the hegemonic discourses that have prevailed in Colombian ELT, one of the goals of this research was to also display moments of counter hegemony where ELT scholars have been actually resisting hegemonic influences. Overall, the analysis of the several texts compiled allowed determining that even though governmental entities still decide what is ultimately taught within the context of the educational scenario, national ELT scholars have been advocating for the inclusion of knowledge otherwise, as well as for more equitable power dynamics. Hence, it is possible to affirm that the Colombian Government and ELT policymakers have a low interest in listening to the voices of all stakeholders to implement a more equitable policy-making process.

Even though it is observable that the whole situation resembles a David vs. Goliath battle, ELT scholars have been firm and continue conducting research studies that seek the recognition of the other, integrating epistemologies, identities, and knowledge that had been historically marginalized in the ELT scenario. In this vein, it is paramount to keep implementing these initiatives so that, at some point, we have the opportunity to assume more active participation in ELT policy-making processes.

Finally, even though all stakeholders’ voices have not been heard at all, and even if, for the most part, national language policies and entities serve international hegemonic purposes, the incorporation of our local knowledge has begun to gain traction in academia and other formal spaces (e.g., in conferences, ELT journals, and our classroom contexts). Hence, in order to keep resisting the influences of hegemony in ELT, it becomes necessary to continue doing research in areas revolving around teachers’ local knowledge, world Englishes, English as a lingua franca, and indigenous communities’ experiences and identities, to mention a few.

This is because, although these areas have been gradually incorporated into the field, more initiatives are necessary if the academic and non-academic community seeks to fully appropriate knowledge that acknowledges diversity and the other as an equal one.