Introduction

The lives of Colombian people have been marked by more than five decades of armed conflict, experiencing it directly or indirectly. In 2016, after four years of dialogues, President Juan Manuel Santos finally signed a peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the oldest guerrilla group in Latin America. This historic event brought great hope of social change. However, contrary to all expectations, in a plebiscite intending to ratify it, a majority of voters said no. How can this be understood? Although different factors might have influenced the shocking results of the plebiscite, the preceding media campaigns to win voters on both sides undeniably played a defining role in this decision (Botero, 2017). On the one hand, the political forces supporting the peace agreement were too confident and focused on explaining and selling it as the best possible choice. On the other hand, right-wing opponents’ intense media campaign proved to be effective through incendiary speech, distorted information, and the primary purpose of arousing feelings of anger and indignation among the electorate (Botero, 2017).

This transcendent event evidenced the tremendous impact of the media on public opinion, the construction of democracy, and the dynamics of politics (Reyes & León, 2016). It also revealed the urgent need to educate Colombians as critical media consumers who recognize war as a battleground of opposing narratives where the truth has been one of its main victims (Murillo, 2017); in this battle, different agents and forms of violence are legitimated (Gómez Arévalo, 2015), and some groups benefit by keeping economic and social control. Therefore, it is paramount that Colombians gain awareness of their role in perpetuating violence and discover their vast potential to contribute to peacebuilding. Undoubtedly, language educators can make a significant contribution in this direction and critical peace education can offer alternative frames of thought and action to take on this responsibility.

Critical peace educators maintain that peace can only be achieved if the causes of violence are tackled, in other words, if equitable conditions are created for everyone (Bajaj, 2015); this requires a transformation of education. Recognizing this possibility in foreign language teaching, and particularly in ELT, demands a shift from seeing language as an object of study to seeing it as a means that produces social realities (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2012). This move also implies seeing education and language teaching as sites to raise awareness about the way language reproduces and creates unfair power relationships (Kruger, 2012), and as intertwined in sociopolitical and historical contexts (Pennycook, 1990). Fortunately, this move has started to take place in Colombian ELT.

Recent research reveals an increasing interest in transcending instrumental approaches to English teaching and re-orienting practices to impact school communities’ unequal, violent realities. Within these efforts, some researchers have identified the need to use different theoretical perspectives related to peace education. For instance, Aldana et al. (2020) used peace education to explore how fifth-grade Indigenous children, who were victims of the conflict, could build memory artifacts to re-elaborate their traumatic memories and contribute to their healing process. Similarly, using the lenses of social justice and critical pedagogy, Ortega (2020) collaborated with an English teacher in an underprivileged neighborhood in Bogotá to sensitize her ninth graders about the social inequalities surrounding them and to take action for change. By the same token, Bello (2012) studied undergraduate students’ discourses of their social realities through discourse analysis and citizenship competences. Likewise, Romero and Pérez (2021) drew on citizenship and communicative competences to discuss global warming with ninth graders and engage them in reflection and the search for solutions as responsive citizens. These studies were conducted in disenfranchised contexts in public institutions across different educational levels, which confirms that it is possible to use ELT contexts as rich scenarios to educate critical citizens who take an active role in the transformation of their realities.

At an international level, some researchers have introduced different theories and concepts from peace education (PE) and critical peace education (CPE) in teacher education programs and courses. For example, Arikan (2009 focused on preservice ELT teachers working on grammar through environmental peace education activities to discuss social issues from a global perspective in their classrooms. In addition, Christopher and Taylor (2011) used critical reconstructionist perspectives to raise awareness of social and economic injustice and the defense of human rights, which resulted in student teachers wanting to turn their classrooms into places for justice.

This type of work shows a valuable path to follow considering that our social realities in Colombia have been historically permeated by war and violence. We strongly believe English preservice and in-service teachers in our country could better respond to the demands of our social realities. This can occur if they become critically conscious of how violence operates at the micro and macro level, the role of media in these dynamics, and their potential to promote peace starting from their practices as language educators. We believe it is time that this work capitalizes on the many contributions to peace education made by Colombian and other scholars in our region that help us understand this phenomenon from our place.

Acknowledging this need, the present study targeted a group of preservice teachers in a foreign language teacher education program at a public university branch in Antioquia, a region affected by cultural, structural, direct, and ecological violence. The study resorted to CPE, pedagogy of memory, and CML to foster critical consciousness of our country’s armed conflict in these preservice teachers while weaving different ways to teach English that contribute to peacebuilding. In this vein, the study intended to answer the following research question: How can the implementation of a pedagogical unit based on CPE, pedagogy of memory, and CML enhance foreign language student teachers’ critical consciousness about the representations of Colombia’s armed conflict promoted by mainstream media?

Theoretical framework

This study drew on critical approaches to peace education and literacy. In this section, we first introduce CPE and its principles; then we present pedagogy of memory as a critical approach within CPE and its relevance to work on PE initiatives in our context. Finally, we introduce critical media literacy’s principles and core concepts as valuable frames and tools to work with English learners on the analysis of the role of media in the dynamics of violence, conflict, and war.

Critical Peace Education

PE stands as an international movement working for the elimination of all forms of violence, the transformation of educational praxis in diverse contexts around the world, and the construction of peaceful, just social structures where human rights are respected (Bajaj, 2015; Galtung, 1990; Gómez Arévalo, 2015). This study was guided by critical peace education (CPE): A political approach to PE because it maintains that social change can occur both inside and outside school, reclaiming engaged action and analysis of local contexts (Haavelsrud, 1996, as cited in Bajaj, 2008). For critical peace educators, it is paramount to analyze the connections between school and its larger social context. They claim that unbalanced relations of power and their causes generate inequality, which education and social action should dismantle; learning processes should revolve around local meanings and realities to promote students’ agency, democratic participation, and social action; and all educators should critically reflect on their role and positionality regarding education (Bajaj, 2015).

Framed in these principles, CP educators attempt to unveil and disrupt direct, structural, and cultural violence. Direct violence is perpetrated by specific actors while in indirect or structural violence their perpetrators cannot be identified since this type of violence is built in the system and is evidenced in the unequal distribution of power and unequal opportunities (Galtung, 1969, as cited in Kruger, 2012). In addition, cultural violence is present in symbolic aspects of human existence like religion, art, language, science, and ideology that can be used to justify direct or structural violence (Galtung, 1990). In addition to understanding how different forms of violence operate, CP educators work to construct positive peace.

Positive peace is understood as the absence of structural violence and the elimination of its causes (Brantmeier, 2013; Galtung, 1969, as cited in Kruger, 2012). It entails the presence of social justice, equity, environmental sustainability, and the fair distribution of resources (Brantmeier, 2013). This view of peace identifies with the principles of CPE. However, mainstream discourses and initiatives towards peace understand it as the absence of direct violence disregarding the structural causes of violence; this view is known as negative peace. In sum, embracing a critical perspective on PE encompasses varied principles that include not only a deep understanding of the different types of peace and violence but also an analysis of the power structures in which they operate in specific contexts.

Critical work in PE entails analyzing and critiquing structural issues affecting society, paying attention to local meanings, and engaging different voices, encouraging equal participation, and promoting agency (Bajaj, 2008; Bajaj & Brantmeier, 2011; Hantzopoulos, 2011). In the analysis of structural issues, learners pay attention to both power relationships (Brantmeier, 2013) and structural inequality (Bajaj, 2008) to question dominant narratives of peace and violence (Gounari, 2013). It is equally important to address situations in learners’ local settings (Bajaj, 2008) and consider the local understandings of peace and violence (Brantmeier, 2013) for devising possible actions to transform reality. CPE also intends to hear multiple voices, especially those coming from learners’ own experiences (Freire, 2000) to compare the narratives of both dominant and disenfranchised groups.

Pedagogy of Memory

In tune with the CPE idea that understanding and analyzing social structures to understand the dynamics of violence should be grounded on local meanings and realities, this study was also enriched by a locally developed perspective of PE, i.e., pedagogy of memory. Pedagogy of memory aims to create spaces for dialogue and understanding and strives to construct an inclusive historical culture based on the motto never again (Torres, 2016). It involves working with people’s memories about their experiences and feelings (Aponte, 2016) as fundamental to reaching peace and justice (Arias, 2016) and avoiding human rights violations (Sacavino, 2015). Likewise, pedagogy of memory can enhance the reconstruction of social bonds by listening to victims’ voices (Mayorga et al., 2017) and examining the perspectives of all war agents in their social and historical contexts (Padilla & Bermúdez, 2016). Such considerations will disrupt hegemonic representations of social groups (Garzón, 2016) and support learners in developing a more comprehensive understanding of conflicts (Padilla & Bermúdez, 2016).

By the same token, pedagogy of memory becomes particularly relevant to the Colombian context since we seem to be immersed in total obliviousness (Ospina, 2013). Such disregard for our memory is especially evident in schools where violence is not a topic of discussion; instead, civic instruction emphasizes the regulation of citizens’ behaviors (Murillo, 2017). Sadly, oblivion stands as the main feature of our political culture (Garzón, 2016), which takes a toll on both election days and the way our young students understand war.

Critical Media Literacy

Working with pedagogy of memory also sets the need to develop critical views of the media with the student teachers participating in this study. This is because it is vital to reinforce the testimonies disclaimed by the mainstream media (Murillo, 2015) and to recognize that war is a battlefield of different narratives (Murillo, 2017). Therefore, in this study, critical media literacy (CML) principles and pedagogical tools supported the analysis and creation of media texts about the Colombian armed conflict.

CML is a practical approach to critical literacy that engages learners in analyzing and critiquing media messages regarding how power operates among audiences, media, and content (Gainer, 2010). For doing so, CML includes different forms of literacy such as the use of new technologies, analysis of mass communication, and critical consumption of popular culture; it also enhances the creation of alternative media “to challenge media texts and narratives that appear natural and transparent” (Kellner & Share, 2007, p. 4).

CML provides learners with opportunities to analyze and question media messages, unveil structural relations of oppression and make their voices heard. Through CML, learners can develop skills to uncover hidden messages in lifestyles, values, and worldviews promoted by media texts. They might also examine different issues affecting their lives, make connections to what happens in society (Kellner & Share, 2005), and make their voices heard through the creation of alternative media texts (Gainer et al., 2009). Hence, this type of work enhances the use of the media to promote social change and positions students as citizens responsible for constructing a better society (Kellner & Share, 2005). Such work is guided by CML key concepts, which can help learners deconstruct and reconstruct media messages about peace and violence and critically reflect on them.

Media educators share five key concepts that guide the critical analysis of media texts (Kellner & Share, 2005). First, media messages represent reality in a particular way (non-transparency); second, the media have their language and rules to construct messages effectively (codes and conventions); third, people may have different interpretations of media messages (audience); fourth, the media support certain values and worldviews (content and message); and finally, the media are driven by an interest in profit and power (motivation). All these guiding concepts have the potential to enhance students’ critical reflection about their own views on peace and violence, the local dynamics of power that generate violence, different types of violence that are promoted by the media in their local context, and the forms of violence they are involved in on a daily basis. In the following section, a description of the method used in this study will be presented.

Method

This inquiry process was a qualitative case study. According to Yin (2003), a case study is useful to explore situations in which a specific intervention may produce undetermined outcomes; a case study can be used under three conditions: when trying to answer “how” and “why” questions, when the behaviors of the participants cannot be manipulated, and when investigating contemporary phenomena in a particular context. The work presented in this paper stands as a single case study since a single pedagogical intervention consisting of a CML unit was conducted; it examined a contemporary phenomenon: how foreign language student-teachers interrogated views of peace and violence promoted in local media; and it was conducted in an English oral and written communication course in a foreign language teacher education program at a public university.

Participants

Participants were selected using criterion sampling (Patton, 1990). In this case, the three student teachers selected have had very different experiences with the armed conflict, and they showed different levels of awareness regarding underlying media messages. We will refer to these participants as Felipe, Hernan, and William to guarantee anonymity.

Felipe is a 26-year-old FL student teacher coming from a public high school and lives in eastern Antioquia with his mother and sister; he belongs to a low social stratum and works as an apiarist. Felipe thinks he has indirectly experienced the armed conflict, mainly through the media and other people’s experiences. He keeps himself updated on the country’s situation through the mainstream national and local media.

Hernan is a 22-year-old FL preservice teacher, from a middle-low social stratum, who finished high school in a public institution. As a teenager, he had to deal with urban violence in his neighborhood (Narrative, April 13, 2018). He reads national magazines, watches local TV channels, and listens to local radio stations to be updated; he emphasizes the importance of verifying information received from any media source (Survey, February 26, 2018).

William is a 23-year-old FL preservice teacher coming from a middle-low social stratum. William’s family was displaced by the armed conflict when he was just a newborn. Despite the tragedies he witnessed, he got involved in NGOs by working with victims of the armed conflict. As a representative of the armed conflict victims in Antioquia, he has worked to defend human rights and in the construction of proposals for the peace agreement (Narrative, April 13, 2018). As a social activist, William often tries to be informed about the country’s situation through the national mainstream media.

The Pedagogical Intervention

The study was conducted in a foreign language teacher education program at a public university in Antioquia, Colombia, at one of its regional branches. It involved a pedagogical intervention in a fourth-semester English oral and written communication course. Classes took place four hours a week over seven weeks. This intervention integrated the course objectives with work on CML, CPE, and pedagogy of memory as illustrated in Table 1. These objectives included providing critical reflection spaces and promoting the development of the four language skills, particularly inferring main ideas from oral and written texts, composing different texts, and supporting main ideas in a talk.

Table 1 Course Objectives

| Course Objectives | CML Objectives | CPE Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| To show comprehension of informative, narrative, and argumentative oral and written texts about topics of general interest and related to the field of foreign language teaching. To state and argue their viewpoint in oral presentations and debates in relation to academic and professional matters. To summarize authentic argumentative, narrative, and informative texts. To participate in conversations about controversial topics. | To guide students in analyzing and creating media texts about the Colombian conflict in terms of authorship, audience, content, and purpose. | To compare the voices of victims, the State, war agents, and the media. To provide spaces for dialogue and reflection on the causes and consequences of the armed conflict in Colombia. To reflect on both individual and local conceptions of peace, violence, and agents of violence. |

As for CML objectives, the pedagogical project attempted to guide students in analyzing and creating media texts about the Colombian conflict in terms of authorship, format, audience, content, and purpose. In this vein, CML’s guiding concepts and questions included: (i) Who created this message?; (ii) what creative techniques are used to attract my attention?; (iii) how might different people understand this message differently?; (iv) what values, lifestyles, and points of view are represented in, or omitted from, this message?; (v) why is this message being sent? (Jolls & Sund, 2007). In addition, several pedagogical strategies from pedagogy of memory provided spaces for dialogue and reflection in the classroom to construct knowledge collectively. Such tools included questions and practical activities based on interactive techniques from qualitative research in social sciences, which are proposed by Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (CNMH, 2013), namely, debates, discussions about objects that elicit people’s memories, analysis of photographs, and the creation of videos. Working towards CPE and pedagogy of memory involved comparing the voices of victims, the State, war agents, and the media; identifying the causes and consequences of the armed conflict in Colombia; and reflecting on both individual and local conceptions of peace, violence, and agents of violence.

Lessons were planned based on the backward design model proposed by McTighe and Wiggins (2004) to ensure they were oriented toward the desired results. This design model offers a guide to organizing content so that it makes sense in all its stages (desired results, assessment evidence, and learning experiences) without becoming prescriptive. Using this design model, one of the main learning experiences planned was the creation of counter-texts challenging official views of peace, violence, and war agents presented in media texts.

The first counter-text was a speech bubble activity in which students observed original images of war agents and created their own counter-ads using bubbles. The last counter-text was a podcast or a video presenting their views of the Colombian armed conflict as well as their own experiences. For the creation of the different texts, students were asked to consider and make decisions about text type, format, contents, audience, and purpose. In order to do this, students were also guided by the five CML core concepts in the light of the following questions for the construction of media texts: What am I authoring? Does my message reflect understanding in format, creativity, and technology? Is my message engaging and compelling for my target audience? Have I clearly and consistently framed values, lifestyles, and points of view in my contents? Have I communicated my purpose effectively? (Jolls & Sund, 2007). In the following section, we describe the data collection methods used in this study.

Data Collection

Data collection took three months and included a survey administered to the whole class, recordings of the six course class discussions, three samples of students' work, one individual interview, and two group interviews also conducted with the whole class. At the beginning of the course, students received information about the study and the selected participants signed a consent form. They also completed a survey in Spanish to provide data about their background, media consumption habits, and theme preferences.

These results informed the unit design. Through the intervention, students participated in critical class discussions that were held in English and recorded to observe both students’ language performance and to examine their views on media messages, peace, violence, and agents of violence. They also created different artifacts in English including a personal narrative about their experiences with violence in Colombia and two counter-texts: A speech bubble activity and a podcast or video. These artifacts showed how learners engaged in the deconstruction and reconstruction of media messages related to peace and violence in the armed conflict of our country and whether they presented critical counter-narratives that challenged mainstream media messages. At the end of the course, students participated in one individual and two group interviews that allowed researchers to collect data about learners’ views of peace and violence and compare them to the initial views expressed in the survey, to examine new attitudes and positions towards media texts, and to know about their perceptions concerning the implementation of the pedagogical project. These interviews were conducted in Spanish. In this paper, we translated into English data that were collected originally in Spanish. Finally, three participants were selected in terms of their experiences with the armed conflict and their levels of consciousness regarding media messages about the class topics.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a constructive method in which some categories and codes were created by combining both deductive and inductive methods (Altrichter et al., 1993). Therefore, there were some pre-established categories based on the theories that guided the study and others that emerged from the data. The pre-established categories attempted to feature the critical consciousness that students may develop; they included analyzing the local context, challenging unbalanced relations of power, and identifying all sorts of violence. On the other hand, those categories emerging from the data revolved around recognizing the need to challenge mainstream media and identifying language teachers as technicians.

The process was fluid and involved managing and knowing the data, focusing the analysis, categorizing information, identifying patterns, making interpretations, tracking choices, and involving others (Suter, 2012; Taylor-Powell & Renner, 2003). After the initial familiarization with the data, all the information was uploaded to NVivo 10 in order to code it and easily retrieve such codes (Bryman, 2012). Taking this initial analysis into account, some brief reports were written. During the process, the pre-established categories were refined, emergent categories were added, and the case of each participant was analyzed and reported separately. These reports were discussed and compared in order to discover new patterns as well as commonalities and differences in the participants’ processes and understandings; thus, the categories were reshaped, and the findings were presented in an integrated manner.

Findings

Through this pedagogical intervention, participants could develop more complex analyses of the representations of Colombia’s armed conflict in mainstream media. Critical discussions around different media texts helped students gain a better understanding of the dynamics of violence, its causes, and its multiple forms. Such texts also allowed for challenging dominant or limited representations of war agents, giving prominence to the voices of disenfranchised groups, and gaining a better understanding of the media’s role in the perpetuation of different forms of violence. This section accounts for the three participants’ views, contradictions, and realizations along the stages of the intervention.

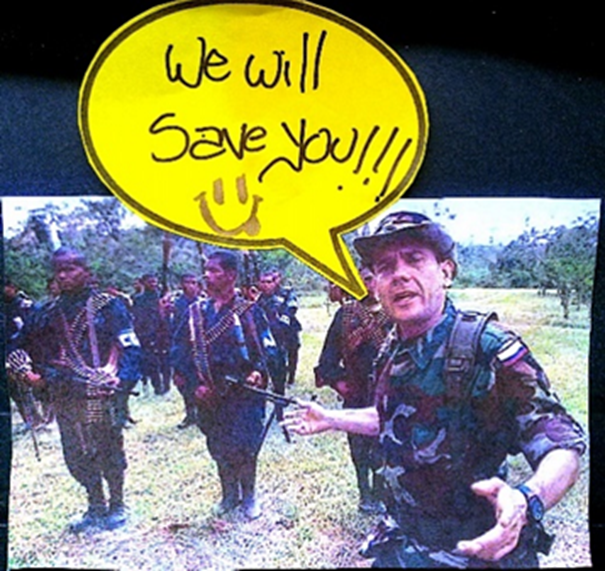

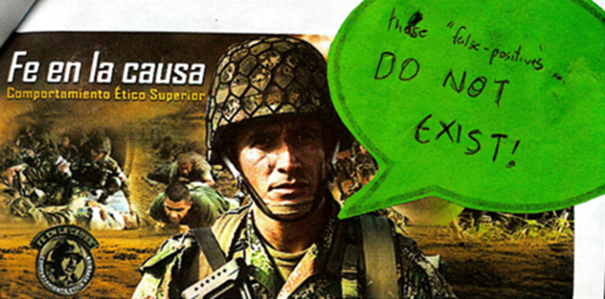

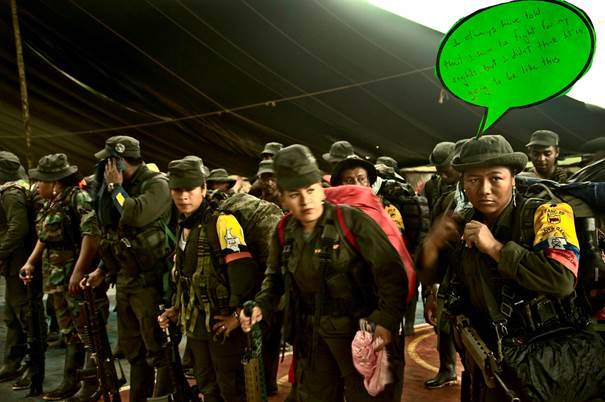

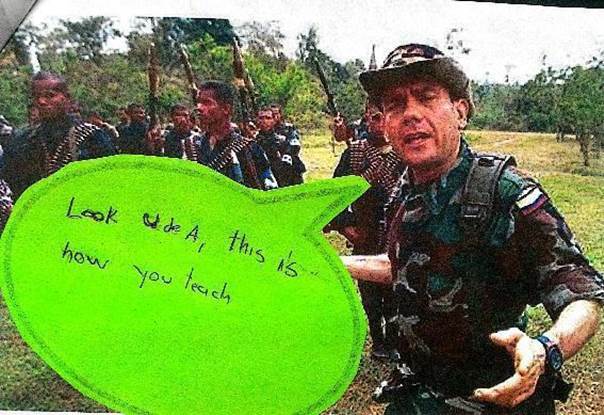

What War Looks Like

Felipe, Hernan, and William had different perspectives on the armed conflict in Colombia. Coming from different life trajectories, these three student teachers perceived violence, war agents, and peacebuilding in different and sometimes contradicting ways. At this initial stage, students participated in a speech bubble activity based on a series of pictures taken from different media and related to the war in Colombia. They had to observe the images and respond to them in a bubble. In this activity, Felipe and Hernan focused on portraying war agents as crime perpetrators. They used sarcasm to refer to paramilitary groups (see Figure 1), the incompetence of state forces (see Figure 2) and to big scandals such as false-positive cases1 (see Figure 3), and male prostitution in the army (see Figure 4).

Source: Policía Nacional de Colombia, 2011, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/policiacolombia/5885648462

Figure 2 Speech bubble text by Felipe

Source: Policía Nacional de Colombia, 2011, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/policiacolombia/5885648462

Figure 4 Bubble Speech by Hernan

However, some of their reflections went further to challenge widespread representations of some war agents in the mainstream media. For instance, when referring to guerrilla members, Hernan explained that he attempted to portray them as victims since they might regret their actions, suffer when committing violent acts, and be afraid and troubled because of the horrors of war (see Figure 5). This reflection shows that he could detach from official perspectives that tend to demonize certain groups and legitimize State forces as naturally well-meaning agents.

Data also showed that students could identify direct violence. When describing their previous experiences, Felipe mostly referred to destruction, kidnappings, murders, and fear caused by the armed conflict as he described what he saw in the media: “the journals and TV news showing people dying, going to other places because of violence and a lot of houses resting on parts on the ground after the attacks” (Felipe, narrative, April 13, 2018) . In turn, Hernan narrated how he witnessed visible manifestations of violence in his neighborhood:

[…] Many of them [my friends] died due to a war between gangs, some other [because of] the famous limpiezas [social cleansing]. I really felt sadness in my heart when a young [boy] died in my neighborhood. Besides [this] feeling, I also felt gladness because it was not me; thanks to my parents, I took another way. (Hernan, Narrative, April 13, 2018)

In addition, students could perceive some more subtle forms of violence around them. In the speech bubble activity, Felipe represented gender violence and explained that female guerrilla members suffer discrimination since they have historically been assigned certain roles in society (see Figure 6). Similarly, William referred to some invisible forms of violence, including discriminatory comments against his university that portray it as an institution that trains guerrilla members (see Figure 7), which is a widely spread stereotype in the local context.

Source: A. Gómez, Mujeres guerrilleras. Flickr, 2017, https://rb.gy/z5sh2u

Figure 6 Speech bubble by Felipe

William and Hernan also expressed their views of the role the media have in the conflict. In the first-class discussion, William stated, “all the media is promoting good education and information.” (William, class discussion, March 12, 2018) On this occasion, Hernan stated that even if the FARC had committed deplorable actions, the media should present the perspective of this group so that they convey neutral information: “it’s difficult because FARC we know that they hold a wrong perspective and have done bad things, but maybe [the media should] show the perspective of the FARC too” (Hernan, class discussion, March 12, 2018). In these statements, students did not seem to recognize that all media texts have purposes and intentions, and therefore, they cannot be neutral or naturally well-intended. However, Hernan highlighted how the media should include the perspectives of different agents in the conflict when covering the news.

A very significant finding at this stage was that the three participants recognized people’s transformative potential to change their realities and work towards peacebuilding. To Hernan, “education can cultivate critical individuals that are not easily manipulated by politicians” (Hernan, survey, February 26, 2018, own translation). He saw peace and violence as closely linked to ELT since “teachers can use English as both a means to inform about the context of our country and as a tool to teach a language” (Hernan, survey, February 26, 2018, own translation). In this same direction, Felipe and William recognized the commitment of the government, armed groups, and citizens as fundamental to putting an end to the Colombian armed conflict. William also highlighted “the need to empower people to work towards this goal” (William, survey, February 26, 2018, own translation); in fact, he was personally committed to the creation of scenarios for peace and reconciliation in his role as an activist: “We have built proposals in favor of the victims. These proposals have been presented to the government with the interest of [making the victims] part of the [government] projects. We have participated in mobilizations for the peace agreement” (William, narrative, April 13, 2018). It is interesting to see in these statements how the three students are aware of their agency in the transformation of violent realities and show different levels of personal involvement in achieving this goal.

Interrogating Grand Narratives About the Armed Conflict

Through this pedagogical intervention, Felipe, Hernan, and William gained awareness of the role of different war agents in the armed conflict, increased their capacity to question the truths presented in media texts, and recognized the relevance of including the victims’ voices in the narratives about the conflict.

In the first place, students gained awareness of the involvement of different actors and war agents in the conflict. Felipe, for instance, moved away from his initial focus on guerrilla groups as the only party perpetrating violence; in a discussion about a newspaper article, he stated, “[the] FARC […] had an ideology but these other armed groups they don’t have any ideology, they only fight for money and to control the traffic, the drugs and that” (Felipe, class discussion, May 7, 2018). He went further to include other actors whose actions increased the intensity of the conflict: “the armed groups, political forces that create polarization among citizens, and Colombian people who behave indifferently and do not take actions” (Felipe, group interview 1, May 21, 2018, own translation). In addition, during the implementation, students worked with several videos about 2016’s plebiscite from an online campaign inviting Colombians to reject the peace agreement. When analyzing one of these videos, guided by the five CML concepts, William claimed that even if most voters had approved the peace agreement, it would have just meant the end of the conflict with one group:

In the] other video Colombia is showed as a best country but [if] the [YES-vote] in favor of the peace agreement is approved it represents the [end] of the conflict with only one armed group and in Colombia there are other groups that are not included in that peace agreement (William, class discussion, March 21, 2018).

As it can be observed, William recognized the importance of including all war agents in order to work towards peace. These examples show how students could bring new elements to the analysis of the conflict by acknowledging the role of other actors who may not exert direct violence and that the peace agreement was just a beginning in the search for peace.

In the second place, data also showed that students could widely question spread narratives about the conflict in the mainstream media. In one of the class sessions, students discussed an online campaign about the plebiscite whose main argument was trying to convince voters in this video that guerrilla members would not go to prison if the peace agreement were validated through the plebiscite (Campaña por el NO en el plebiscito[CPNP], 2016). In this activity, Hernan cast doubt on whether “paying a guerrilla ex-combat eight million Colombian pesos for running a business would be more or less expensive than sending them to prison” (Hernan, class discussion, March 21, 2018, own translation). Moreover, he criticized the techniques used in the video to achieve its purpose as he stated, “there are no arguments in the videos, they are just playing with your feelings” (Hernan, class discussion, March 21, 2018).

Similarly, when examining another video from the same campaign (CPNP, 2016), William could unveil some omissions in it. In this text, the main argument for voting for no included all the economic benefits that the peace agreement would grant guerrilla members while working-class people could barely feed their families. Here, William called his classmates’ attention to the fact that the commercial did not explain how people’s poor working conditions were going to change by voting for no in the plebiscite, as he stated: “If the NO [vote] wins, the situation of Javier won’t change.” (William, class discussion, March 21, 2018). In this activity, students could question the main arguments presented as truths in this media campaign. They assessed the validity of the information presented, the techniques used to create those messages, and what these messages omitted. This allowed them to realize that the dynamics of the conflict in Colombia are in no way black or white and that the views of the conflict presented in them have specific purposes.

Thirdly, students also emphasized the need to consider the victim’s perspectives to understand the conflict better. In one of the class discussions, students scrutinized some photographs representing different versions of the conflict. They described the photographs, evoked memories of events and places marked by war, and compared the voices of the victims, the state, and war agents in the conflict. This interactive technique, which comes from social studies, intended to set up a dialogue between the content of the photographs and the interpretations students may have about the social reality of their country. In this activity, Hernan was moved by one image showing an indigenous woman who had been injured by a landmine and was smiling despite her tragedy, in this case he stated that “she lost her both hands and one eye, but in the picture she is smiling, so it’s a very nostalgic image” (Hernan, class discussion, April 9, 2018). Furthermore, Hernan was able to identify the voices omitted from a newspaper article addressing issues of violence in Colombia (The Guardian, 2004). He noticed that the original article focused on the perspective of paramilitary groups; therefore, he selected a new article that addressed different situations faced by children recruited by paramilitary groups. He stated,

In this article, we found that they omit the other perspectives. They only focus [on] the paramilitaries’ perspective, so that was the reason we took these two articles: BBC News and CBC News, and here we made a little comparison. For example, this [one] called our attention because this talks about the children who are in the paramilitary groups, and it was the only [one] that mentions children in the news (Hernan, class discussion, May 7, 2018).

In the same activity, William’s concern about the victims was also evident in the analysis he did of a newspaper article related to peace and violence in Colombia. He suggested an alternative heading to transform the original news article: “Victims support YES in the plebiscite”, which he considered a text that advocated for making victims’ voices heard: “[it] is very similar the structure of the text but the main difference is that here in this text, [the] main characters are the victims, and the voices of victims are the most important in this article” (Class discussion, May 7, 2018).

As shown before, the three participants gave prominence to the voices of victims, their suffering, and their struggles, which in many cases are overlooked in official narratives. They assessed the intentions, omissions, and techniques of media messages and took an active role as readers and viewers, these student teachers could deconstruct widely spread official narratives about war agents, their motivations, actions, and impact on people’s lives.

New Understandings, Different Perspectives, and New Texts to Build Peace

The final project in this pedagogical intervention was conceived as an opportunity for students to create a video or a podcast with their perspectives on the Colombian conflict. In their work, they decided to rebel against the stigmatization of Colombia as a violent country and give prominence to victims’ voices. They also made connections on how violence is present in their daily lives, discussed media manipulation, and reflected on their potential to contribute to peacebuilding. This was in no way a linear path of achievements; there were many gains as well as doubts, feelings of frustration and sadness, and even, some rebellion in students’ counter-texts.

In his project, Hernan showed other forms of violence by creating a media text that was totally different from the ones analyzed in class. His final podcast aimed at changing the way people see Colombia and it was titled the risk is wanting to stay. Hernan introduced his podcast, referring to the damages caused by the armed conflict: To him, Colombia should not be a synonym for violence and fear anymore; therefore, he invited foreign people to visit our country and fall in love with its places. In his podcast, he stated: “People will realize that there are other interesting facts about Colombia despite war and drugs. You will know that Colombia is full of beautiful places to visit and that people is really different to what you may think” (Hernan, podcast script, May 12, 2018). This text shows his understanding of violence as not only direct aggression but also as the beliefs, attitudes, and actions that end up in rejection or discrimination of individuals and groups. At the same time, his view may be seen as a kind of rebellion to continue talking about war and conflict, considering that, at the end of the intervention, Hernan confessed that discussions around these topics had become monotonous to him. Interestingly, his feeling of boredom led him to create a very original text, which might show that even these unexpected reactions by students can become learning opportunities.

Regarding Felipe’s project, he decided to show the importance of telling the stories of victims whose perspectives are not usually included in the media. He made a video explaining the dynamics of the Colombian conflict. As he presented his work, he revealed the importance he gave to the victim’s testimonies, which was evident in its title it is time to remember and content: “In this video, [the victims] tell us their experiences in the armed conflict. In this way, we construct the narration from their memories” (Felipe, sic, video recording, April 11, 2018). Felipe also included other disregarded voices from the grand narrative of the armed conflict, particularly those of peasants and rural teachers:

Our video mainly represents the lifestyle of peasants, rural teachers, their struggles, and resistance in the armed conflict. It also unveils the value of life, the family, and education from the victims’ point of view. For example, in the story of Mr. Arsenio Marulanda, we can rescue values such as honesty and integrity. Also, the unconditionality of how Mrs. Luz Amparo Córdoba faces the situation of [...] education in conflict areas. In addition, the snippets of poems of Amador López show us the drama of forced displacement, the longing for home and faith. (Felipe, video script, April 11, 2018).

In the same vein, William created a podcast in which he emphasized the transformative role of the victims to put an end to the armed conflict. When talking about who benefited from his message he replied: “The victims of the armed conflict, because this information is a way to sensitize others about the damage generated by the war [and] the work [done] by the victims to overcome this [situation] and not [to] repeat it again” (William, sic, podcast script, May 12, 2018). Moreover, William was aware of the causes and consequences of the armed conflict as pivotal elements to understanding this issue and trying to solve it. With his podcast, he wanted the audience to understand “the main reasons for the conflict [to start], why and how it has continued, and the current consequences that have been generated” (William, podcast script, May 12, 2018). This reflection shows how William remained consistent with his idea of the armed conflict as a complex issue whose causes, consequences, and agents need to be better understood so people can unlearn the war.

Together with their analyses of violence in Colombia, students could make very close connections between media manipulation and violence. Felipe expressed his lack of trust in the purposes of the mainstream media in Colombia since sometimes they seem to pursue noble intentions, but at the same time, they misinform people:

The truth is that I do not know what to think about violence and the whole situation in Colombia because [the media] show a lot of information and you do not know if they are really trying to help to make things right or they are simply trying to make profit and they keep harming society. (Felipe, group interview 1, May 21, 2018, own translation).

In this regard, Hernan insisted that the media should be “neutral” while Felipe claimed that this could not be possible for they serve specific interests, and this does not allow them to tell the truth:

“The media obey different interests and while they are not neutral, they won’t be able to provide, let’s say, truthful information” (Felipe, group interview 2, May 28, 2018, own translation). This shows how Felipe stepped away from his initial trust in the pure informative nature of the media.

Of great relevance in the findings from this study was the fact that, even if this pedagogical intervention mainly emphasized the armed conflict, students could see how violence is present in every aspect of our lives. Felipe, for instance, referred to Colombia as a violent country where people do not tolerate that you support a different soccer team or that you belong to a different political party:

You can see, let’s say, in more tolerant countries, more open to many ideas that there is , let’s say, peace because you do not see those acts of violence you see in Colombia, that take place because of intolerance. Intolerance, I do not know why, because you are a member of a different soccer team, a different political party, and so forth. (Felipe, group interview 1, May 21, 2018, own translation).

Similarly, William saw violence in people’s adverse reactions towards conflict ranging from lousy management of relationships in daily life to difficulties in reaching peace in the country:

Bad management of relationships because I believe that, in the end, that is what conflict is about, isn’t it? And absolutely all conflicts happen because communication between two or more people is not well-managed. (William, group interview 1, May 21, 2018, own translation).

These examples, as well as some presented earlier in this section, show how these students went deeper in their understanding of how violence operates from an individual to a social level.

Students’ wider understandings of violence seemed to be in tune with their views of peacebuilding. From the beginning of this implementation, as mentioned earlier, they took a clear stance about the need for individual and social action to successfully build peace in our country and the potential of education, particularly of English teachers, to take actions in this direction (Survey, February 26, 2018). At this stage, William ratified his idea of peace as a collective project that all citizens can work for; he regarded “peace not only as a concern of any government program but also as a personal endeavor starting in the family and moving on to other social spheres.” (William, interview, May 31, 2018, own translation). However, he felt discouraged at some point in the pedagogical project and started to think that his work was insufficient to fight against the massive power of the misinformation campaigns promoted by mainstream media. In relation to the campaigns during the plebiscite, he stated:

I think that is disappointing and it is due to manipulation, but rather than the manipulation of information, it is emotional manipulation because that is reflected in the way the campaigns turned out, in the results […]. There are many reasons that rely more on emotion than on reasoning. What else can you do? This is a little disappointing because you feel when you are at the university, participate in some groups and you know you can find ways to be informed and to help educate people, but you realize that there is still a lot missing and that that emotional struggle that takes place and the little things you can do, teaching, is very little.(William, group interview 2, May 28, 2018, own translation).

Despite this and the disappointment generated by the 2018 presidential election results, which he attributed to media manipulation, William stated that his involvement in this pedagogical project motivated him to continue working towards peace. Particularly, witnessing the transformation of some of his classmates, he realized that his desire to change the realities of his country had not faded:

This unit encouraged me to continue making my contribution. Some of my classmates did not know anything about these topics, and now I can see them motivated, interested, and empowered to talk about them. This transformation makes me feel motivated to continue spreading the message of peace, since violence has marked our country and we are not always aware of this (William, interview, May 31, 2018, own translation).

William’s feeling of frustration and Hernan’s boredom concerning the topic of class discussions, presented earlier in this section, were certainly not expected results. Yet, their reactions and the way they dealt with them bring attention to the fact that pedagogical projects addressing sensitive topics such as war and violence are not an easy task, and they should not intend to have everything under control. Instead, these instances reveal that learning spaces, far from always being positive and ideal, encompass the tensions and challenges that humans face in their daily interactions and realities.

In sum, bringing their different life stories and experiences to the classroom conversations around media texts opened spaces for the three student teachers to gain a broader perspective on how different forms of violence operate in our local context. Students could question their own views and see more clearly how media texts can be used to create versions of the world that privilege some and disadvantage many, thus perpetuating violence and inequality.

Discussion and Conclusions

The present study showed that pedagogical work in ELT, particularly with preservice teachers in Colombia, can be enriched by the contributions of scholars in our region working towards peacebuilding along with the international developments of CPE and CML. Participants in this study widened their perceptions of the causes and consequences of the armed conflict and its different war agents, acquiring more elements to better understand their local context, and start judging their social reality (Aponte, 2016). Such principles helped learners understand Colombia’s conflict as a nonlinear phenomenon emerging from various social, political, and economic factors (Torres, 2016). Students’ participation in class discussions, analysis of photographs, and conversations with victims supported their analysis and comparisons of mainstream discourses and opened spaces to validate the silenced voices in the grand narrative of Colombia’s armed conflict (Ortega, 2016). Moreover, the use of CML key concepts and questions helped students analyze and critique media messages to unveil lifestyles, values, and worldviews promoted by mainstream media texts (Kellner & Share, 2005), thus deconstructing commonly spread representations of peace and violence in Colombia, and making their voices heard (Gainer et al., 2009).

Findings from this study are consistent with those conducted with advanced student teachers in different contexts working on topics related to peace and social justice. As in Christopher and Taylor’s (2011) study, student teachers realized their power to work for a more just society starting in their classrooms. This study also identifies with what was found in Arikan’s (2009) study, in which participants developed positive opinions about including PE topics in their English lessons. However, the present research also evidenced that addressing sensitive issues in the language classroom such as violence and social injustice may involve feelings of demotivation, disappointment, and sadness, and language educators should be aware of this as a natural part of learning.

In addition, the present study poses new elements to previous research done with preservice teachers in relation to PE. In the first place, findings revealed that resorting to the principles, core concepts, and critical theories of CPE, developed both at a local and international level, can guide foreign language educators and teacher education programs to better respond to the urgent need of working towards the eradication of violence and the construction of a more equal society in our country. This connection between English language teaching and CPE has just begun to be explored by some Colombian researchers in English classrooms and it seems to be at an initial stage at an international level. In the second place, the pedagogical intervention conducted showed that the development of critical consciousness is greatly enhanced when students’ life experiences and immediate social realities are brought into the classroom to reflect on them, problematize them, and envision actions for change (Gómez Arévalo, 2015). In the third place, findings showed that CML principles and concepts provided students with elements to identify media techniques and purposes and create their own media texts to contest grand narratives about the Colombian conflict, thus moving from reflection to action.

Regarding the limitations of this study, time constraints did not allow a more in-depth exploration of peace and violence beyond the context of Colombia’s armed conflict; nevertheless, participants could make connections between the analysis of the armed conflict and some other conflicting situations in their daily lives. Further research can address foreign language preservice teachers’ critical analysis of different forms of violence in both their classroom and immediate contexts, which may increase their awareness about ways to contribute to peace as a personal endeavor in every setting where they interact with others. Moreover, future studies can devise longer projects that move from the development of critical consciousness and the creation of counter-texts about violence and conflict to action involving school communities in transformative initiatives towards peace.

We hope this study can also bring some reflection on teacher education programs in Colombia. Teaching a language as if it were a mere body of knowledge to be delivered to learners does not match our mission of humanizing the world and does not contribute to building a peaceful country. Some of our future teachers disregard the realities beyond school walls and teacher education programs tend to prepare them to focus on linguistic knowledge while inquiry about educational processes in violent contexts is scarce or nonexistent. Therefore, it is paramount that foreign language teacher education programs revise whether their curricula are preparing future language teachers to be responsive to learners’ realities and to lead pedagogical proposals in their classrooms and school communities that promote the construction of peaceful environments.

This study also pointed out the need to do more interdisciplinary work in ELT to value the contributions of local knowledge. By working hand in hand with other disciplines, the field of ELT in Colombia can become a powerful ally working to educate critical citizens and transformative agents of the violent realities that inhabit our country. This study resorted to international theoretical developments such as CPE and CML and was enriched by local theories around peace and violence that allowed a deeper understanding and analysis of the armed conflict in our country. Further research is needed involving interdisciplinary work that helps us transcend instrumental views of language teaching and nurture foreign language teacher education curricula; this will contribute to preparing language educators that are sensitive to our social realities and willing to construct pedagogical proposals to support school communities’ processes of transformation, reconciliation, and non-repetition.