Introduction

The distribution of relative particles’ use in Spanish has not received sufficient attention considering the large number of linguistic varieties existing in America and Spain. Indeed, research on the subject has only been devoted to those varieties from Santiago de Chile (Olguín, 1981), Mexico City (Palacios, 1983; Mendoza, 1984), Sevilla (Carbonero, 1985), Madrid (Gutiérrez, 1985), Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Herrera, 1995) and a few other Ibero-American cities (DeMello, 1993), but none of the studies has addressed Colombian Spanish varieties in depth.

The present manuscript reports a study that aimed to fill this variationist void through the examination of relative clauses retrieve from the corpus PRESEEA-Medellín (Project for the sociolinguistic study of Spanish from Spain and America). It seeks to answer two questions: firstly, to what extent do social predictors condition relativizers selection in Medellín? And secondly, how do the outcomes of this speech community compare to those of other communities? The main purpose of the study was, therefore, to quantify the degree to which demographic and social predictors such as gender, age, social class, and level of education affect the frequency and distribution of relative pronouns, relative adjectives, and relative adverbs in such a variety. The investigation also intended to replicate and re-examine some of the previous works related to the topic and provide valuable empirical baseline data to help produce subsequent research on Colombian Spanish.

The analysis departed from the hypothesis that extra-linguistic variables can explain a percentage of the variation in the choice of the complementizers que, quien, como, donde, cuando, cuyo, cuanto, and the complex relativizer composed by an article and que or cual, despite the fact that grammatical restrictions are thought to have a major role.

This kind of language studies from a social perspective acquires relevance when it is understood that language has a social function

both as a means of communication and also as a way of identifying social groups, and to study speech without reference to the society which uses it is to exclude the possibility of finding social explanations for the structures that are used. (Hudson, 2001, p. 3)

In this vein, Berruto (2010) recalls that the frequency of cases in which the social aspect determines the internal form of grammar is very low; nonetheless, diastratic variation is expected when the focus of analysis is the distribution in the uses of the structures generated by the grammar. From this perspective, the study sheds light on the variables conditioning relativizers distribution and may be useful to unify dissimilar outcomes found in previous analyses. Additionally, this research fits into the sociolinguistic intention of expanding the knowledge of language variation, seeking to understand the social usage of the linguistic faculty. It cooccurs with other variationist studies carried out in Colombia such as the analysis of subject pronoun expression in Medellín (Orozco & Hurtado, 2021) and the Caribbean (De la Rosa, 2020; Pérez & Camacho, 2021); the research about T-V distinction and nominal address forms in the speech communities of Bogotá (Mahecha, 2021), Cali (Grajales & Marmolejo, 2021) and Medellín (Arias, et al., 2016); and the examination of some sociophonetic phenomena, for instance, the diastratic variation of intonation found in women from Medellín (Muñoz, 2021).

Theoretical Framework

In this section the grammatical rules that condition relative selection and the main problems of their classification will be examined. Furthermore, some studies that have approached the topic from a variationist point of view will also be mentioned to make clear the starting point of this research.

Relativizers

The Nueva gramática de la lengua española (NGLE, 2009)characterizes relative pronouns based on three dimensions: a syntactic one, a semantic one, and a morphological one. From the syntactic point of view, Porto Dapena (2003) believes that relativizers have a double function: They anaphorically reproduce the lexical content of an antecedent, and, at the same time, they serve as a conjunction between a main and a subordinate clause. Spanish relativizers can be part of three paradigms depending on whether they take the place of an argument, adjunct, or attribute (See Table 1, sections a and b), or whether they modify another expression as definite adjectives or quantifiers (See Table 1, sections c, d, and e).

Table 1 Syntactic Classification of the Relativizers

| Syntactic Class | Relativizer | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Pronouns | quien, que, cuanto, article cual, article que | Quien termine el examen debe salir. Whoever finishes the exam must leave. Cuanto diga será usado en su contra. What you say will be used against you. |

| Adverbs modifying a verbal phrase | cuando, como, donde, adonde, cuanto | Avísame cuando llegues. Let me know when you arrive. |

| Possessive determiners | article cual, cuyo | Esa es la niña cuyo padre es piloto. That’s the girl whose father is a pilot. |

| Quantifiers of a nominal phrase | cuanto | Le compraban cuanta cosa se le antojaba. They bought him whatever thing he wanted. |

| Quantifiers of an adjectival phrase or an adverbial phrase | cuan, cuanto | Cuanto más trabajes, mejor. The more you work, the better. |

From a morphological perspective, the NGLE (2009) divides relativizers into those that possess pronominal or adjectival inflection (number: quien / quienes, cual / cuales; gender and number: cuanto[s], cuanta[s], cuyo[s], cuya[s]) and those that behave as adverbs and, hence, do not show any kind of morphological variation (cuando, donde, como). Relativizers can be further split into simple (que, quien, cuando, donde, como) and complex (definite article and cual or que). The forms el cual / la cual / lo cual / las cuales / los cuales are always complex. El que / la que / las que / los que can be considered complex pronouns just when they are not the head of a semi-free relative clause, that is to say, when the grammatical values of the elided antecedent are not retrieved by a definite article (Bello, 2021). As a general rule, “the antecedent of the complex relativizers appears expressly and is always external to them” (NGLE, 2009, p. 44, own translation). This is not the case of example (1), where the relativizer que refers to a determiner phrase that contains an implicit nominal phrase. In example (2), on the other hand, the determiner and the relativizer formed an indivisible syntactic segment (complex relativizer).

(1) ¡El Ø que hizo eso me las va a pagar!

Whoever did it will pay for it!

(2) Las mujeres con las que salgo son siempre malvadas.

The women I date are always mean.

From the semantic parameter, relativizers encompass different semantic features (See Table 2) that are checked in the uttered or tacit antecedent. The NGLE (2009) and Gili (1980) suggest that in free relative clauses the antecedent is contained within the relativizer. Consequently, the adverbs cuando, donde, como and the pronoun quien would comprise in their meaning the constructions el momento en que, el lugar en que, el modo en que and la persona que respectively.

Table 2 Semantic Traits and Relativizers

| Feature | [+Person] | [+Object] | [+Place] | [+Time] | [+Manner] | [+Quantity] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relativizer (Spanish) | Que, quien, cual | Que, cual | Donde | Cuando | Como | Cuan, cuanto |

Regarding the functions that relative pronouns could perform, complex pronouns have in common the fact that they are limited to prepositional clauses while the main differences in their use are caused by prosodic requirements. Que, definite article and que or cual have a complementary distribution: whereas the first is used in clauses without a preposition, complex relativizers are -almost- exclusively used as part of a prepositional phrase. Secondly, the pronoun quien can appear in all syntactic contexts as long as the antecedent has the trait [+ human]. Nonetheless, it cannot be the subject of a restrictive clause unless there is no explicit antecedent (free-relative clause). Thirdly, the adjective cuyo does not perform any argument or adjunct function since it never directly modifies the verb of the subordinate clause. Cuanto, on the other hand, has greater syntactic freedom because, in addition to being an adjective, it is also an adverb and a pronoun. Its use is limited to restrictive clauses without prepositions. When cuanto introduces free relative clauses, it might perform the functions of indirect object, subject, or direct object of appositive relative sentences. Finally, the classification of adverbial relativizers is less sharp: they play for certain the role of adjuncts. Their usage as subjects, direct objects, complementos de régimen preposicional (prepositional complement), and genitive complements are infrequent or very close to the characteristics of indirect interrogatives. Although for traditional grammarians these argument functions are introduced by means of adverbial conjunctions (without antecedent) instead of relative adverbs (with explicit antecedent), this work will adopt the theoretical framework proposed by the Real Academia de la Lengua Española (NGLE, 2009), and therefore, it will accept the notion of implicit antecedent (free relative clauses).

Studies on Relativizers

The study of relativizers usage in Spanish has had rather limited coverage in comparison with other linguistic phenomena. In the 1980s, for example, Olguín (1981) attempted to identify the frequency of relative particles in Santiago de Chile to determine the most usual syntactic functions of the clause and describe the influence of gender and age on those frequency. Considering a corpus of 3,408 tokens, the author found that the average usage of relativizers was higher in the most mature generation than in the other two age groups and that gender did not create any kind of variation in the results. Furthermore, the research revealed that the pronoun que was the most frequent (94.57 %), followed by cual (3.25 %), quien (0.96 %), the adverb donde (0.79 %), and the determiners cuyo (0.35 %), and cuanto (0.08 %).

In another research, Mendoza (1984) described the use of relativizers in the low-prestige norm of Mexico City. He identified 1,495 relative forms belonging to 46 interviewees. In an analogous manner to Olguín (1981), the author found the dominant presence of pronoun que (90.2 %), but in the rest of the cases, the distributions were quite divergent: donde (1.2 %), cuando (0.9 %), quien (0.9 %), cual (0.3 %), cuyo (0 %), and cuanto (0 %). This may indicate a diatopic distinction and a diastratic one, since, as confirmed by subsequent research (Álvarez, 1987; Suñer, 2001), the determiners cuyo and cuanto have almost disappeared from the low-prestige norms and have a very limited scope in the high ones.

In the 1990s, George DeMello (1993) selected eleven corpora belonging to the Proyecto de estudio coordinado de la norma lingüística culta de las principales ciudades de Iberoamérica y de la Península Ibérica (Coordinated study project of the high-prestige norm of the main cities of Latin America and the Iberian Peninsula) to compare the use of the relative pronouns with a human antecedent (article cual, article que, que and quien) in the standard linguistic norm of eleven Ibero-American cities (e.g., Bogotá, Buenos Aires, Caracas, La Habana, among others). The results showed that que lost its primacy in restrictive relative clauses with a preposition and a human antecedent. A case in point is Excerpt 3:

(3) La última es la de un contador al cual entrevisté.

The last one is from an accountant whom I interviewed (DeMello, 1993, own translation)

In this construction, the eleven cities were divided into those that preferred quien (Bogotá, Buenos Aires, Caracas, La Habana, La Paz, and San Juan), those that favored the complex relativizers article cual or article que (Santiago, Madrid, Lima) and those that had no predilection at all (Sevilla and Mexico City).

Two years later, Herrera (1995) examined the use of relativizers in the Spanish variety spoken in Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Canary Islands). The variables of his doctoral thesis included extralinguistic predictors such as age, level of instruction, gender, and sociocultural background. The scholar performed a multiple regression test to infer the theoretical probability of the appearance of relativizers in the speech of 37 participants. Some of the most relevant conclusions concerned the fact that gender had no real effect on the number of pronouns used by the participants. Similarly, the researcher found a negative correlation between age, social level and the number of pronouns produced. Additionally, Herrera (1995) reported greater pronominal variation among women. She also identified a major use of que and a higher volume of prepositional deletion among individuals over 55 and from lower social classes. Example 4 illustrates this:

(4) Un hermano de Andrés {que ⁓ al que} llaman Benito

A brother of Andrés that they call Benito (Herrera, 1995, p. 174, own translation).

Afterward, González Díaz (2001) published a variationist study of que galicado1: a structure in which ‘que’ takes the place of a canonical relativizers in cláusulas hendidas (cleft sentences with the copulative verb before the emphasized phrase and the relative clause, as in Excerpt 5) and cláusulas pseudohendidas inversas (cleft sentences with the emphasized phrase before the copulative verb and the relative clause, as in Excerpt 6): “if the antecedent is a noun phrase (NP), the canonical form must be el/la/lo/los/las que, quien/quienes; if the antecedent is locative, the canonical form is donde; if it is a modal, como; if it is an adverb of time, donde” (Bentivoglio & Sedano, 2017, p. 113, own translation).

(5) Fue entonces {cuando ⁓ que} habló con mi mamá

It was then {when ⁓ that} he spoke with my mother (González-Díaz, 2001, p. 3, own translation)

(6) María fue {quien ⁓ la que} habló con mi mamá

María was the one who spoke with my mother (González-Díaz, 2001, p. 3, own translation)

The researcher examined a spoken corpus of 36 participants from Caracas and identified 152 occurrences of cleft sentences. González Díaz (2001) defined three social variables (i.e., gender, age, and socioeconomic level) and two linguistic variables (i.e., syntactic function and number of syllables) based on previous studies by Sedano (1998), Alario, and Navarro (1997). Findings showed an almost identical percentage of canonical forms use (49.5 %) and que galicado (51.5 %). Also, they revealed that, while age and gender do not have a significant impact on the choice of the canonical pronoun, the socio-cultural level has a substantial effect on it (52 % upper class; 62.7 % middle class; 38 % lower class).

In addition to the description of que galicado in the speech of Valencia (Venezuela), Navarro (2006) also examined the correlation between social predictors and relativizer selection in a corpus of 484 interviews. As in all previous research on the subject, the author recognized a preeminent use of que (65.65 %); however, the percentages were not as extreme as those in Olguín’s (1981) (i.e., 94.57 %), Mendoza’s (1984) (i.e., 90.2 %), DeMello’s (1993) (i.e., 96 %), or Herrera’s (1995) (i.e., 88 %). The next most frequent relative words in Navarro’s (2006) study were article que (19.49 %), donde (10.37 %), article cual (2.35 %), and quien (1.83 %). There was a very limited production of como (0.29 %), cuando (0.22 %), cuyo (0.04 %) and cuanto (0.02 %). Regarding social variables, the researcher observed that the level of education and income class were the only extra-linguistic variables having a real effect on the variation. Conversely, Sedano (1998) discarded these predictors and reported gender as the sole significant variable (women used que more often than men). Alario (1991), in turn, indicated that neither the gender nor the socioeconomic level of young speakers explained the alternation.

Between 2006 and 2018, there were numerous studies on relative pronouns carried out on corpora that, however, aimed at non-sociolinguistic purposes. van der Houwen (2007) for example, studied the use of relative pronouns in Spanish essays written between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries; Balbachan (2011) focused on asymmetries in the use of the definite article and the prepositions in restrictive relative clauses from a semantic-pragmatic perspective; Corredoira (2015) examined relative clauses without an explicit antecedent; López (2016) conducted a functional grammar study on the relativizers in the novel Don Quijote de la Mancha; Álvarez (2018) analyzed the simplification of the relative system from 1950 to 2009 starting from the corpora CORDE, CREA, and CORPES XXI; Vellón (2019) described the evolution and conditions of use of the demonstrative pronoun aquel/aquella as an antecedent for prepositional relative clauses in the corpus CORDE (Diachronic Corpus of Spanish); Lopes (2019) took advantage of the discursive-functional grammar to trace the pragmatic (topic, contrast, focus), semantic ([± definite]), and syntactic constraints that allowed the appearance of the resumptive pronouns in the relative clauses of the corpus PRESEEA.

In conclusion, it is evident from this brief overview that relativizers have been studied assiduously in some varieties of Venezuelan, Mexican and Iberian Spanish, but that in others the research has been very general (e.g., in Lima, Bogota or Buenos Aires) or even absent (i.e., in Medellín). Thereby, it was necessary to carry out an updated study on the subject considering three facts: (1) the little sociolinguistic research on the subject since 2000; (2) the existence of this conceptual gap in some linguistic communities; (3) and the lack of agreement among linguists on the conditioning variables of relativizer selection.

Method

This corpus-based study is inserted in the sociolinguistic scope. It has an exploratory design since it does not consider all the explanatory variables that could account for the variation of relativizers. It uses quantitative tools for the description of the phenomenon such as an analysis of variance (ANOVA) and some post-hoc tests. Two versions of the collected data were proposed: on one hand, the distributions were indicated by taking into consideration the most modern theoretical foundations of Real Academia de la Lengua Española (NGLE, 2009), and in which the notion of relative adverb with implicit antecedent is accepted. This model, especially useful for the analysis of diastratic variation, was named “Medellín - Version 1”. On the other hand, since other studies observed have maintained the traditional differentiation between adverbial conjunction and relative adverb (Herrera, 1995; Mendoza, 1984; Navarro, 2006; Olguín, 1981; Palacios, 1983), this paper offers a version of the results omitting the instances of como, cuando, and donde when they have an implicit antecedent. This version of data is called “Medellín - Version 2”. A further methodological difference is linked to the treatment of the complementizers que and article que, which are distinct relativizers in the NGLE, but are grouped in the same variable in the other studies. Consequently, these relativizers are considered separated variables in “Medellín - Version 1”, whereas “Medellín - Version 2” shows both tokens as part of the same variable.

Corpus and Speech Community

PRESEEA is a project for the creation of a sociolinguistic corpus of Spanish spoken in the most populated urban areas of America and Spain. The corpus of Medellín was collected between 2006 and 2010 by Grupo de Estudios Sociolingüísticos [Sociolinguistic Studies] from Universidad de Antioquia by following a uniform stratified sampling scheme and a system of semi-structured interviews (González-Díaz, 2008). The questions revolved around different familiar topics such as weather, problems of the city, and personal queries about the interviewee’s employment, family, and daily routines, among others. The compendium of audios and transcriptions was made up of 119 interviews of about forty-five minutes each. It included four age groups: young (ages 15-19), first-generation (ages 20-34), second-generation (ages 35-55), and third-generation (ages 56+). The first level was omitted to guarantee comparability with other studies. Consequently, 89 interviews were used. Informants were grouped according to their level of education: primary level (ages 7-13), secondary level (ages 13-19), and higher education level (From second university year on). In the corpus, there were more men (56) than women (33), especially in the third generation and the first level of education (see Table 3).

Hypothesis

Based on the findings from previous studies cited in the preceding section, this research assumed that an amount of the variation in the use of relativizers can be explained by the diatopic parameter (Medellín, Santa Cruz, Valencia, Mexico, and Santiago de Chile) and by diastratic predictors such as age (20-34, 35-54, 55+), gender, level of education (primary, secondary, or university) and social class (upper-middle-class, lower-middle-class, and lower class). They constitute the underpinnings of variationist sociolinguistics and have proved to play a determinant role in language variation (e.g., Bayley, 2013; Berruto, 2010; Chambers, 2009; Silva & Enrique, 2017; Tagliamonte, 2006).

The dependent variables coincide with the relativizers quien, donde, cuando, como, cuanto, and the complex complementizers article cual and article que, while the independent variables are the social predictors. The null hypothesis (H0) assumes a lack of correlation between the predictive variables and the response variables. The alternative hypothesis (H1) implies the existence of diastratic and dialectal influence on the anaphoric choice. This assumption is informed by the different outcomes found in the literature review, which suggest a lack of conclusive information as to the effects of social predictors on relativizers selection (Bentivoglio & Sedano, 2017; Corredoira, 2015; Lopes, 2019; Navarro, 2006; Verrón, 2017, among others).

Data Extraction and Statistical Model

The corpus analysis toolkit AntConc 3.5.82 was used to identify 26,835 occurrences of que, como, donde, quien, cuando, cuanto, article cual, article que, cuyo and their morphological variants. Since the software detected not only the relative particles but also conjunctive, prepositional, and interrogative variants of the words (the corpus is not annotated), it was necessary to proceed to a classification phase of the propositions. Tabulation and data analysis were carried out using the statistical processing software R. The assumptions of normal distribution, independence of data points, homoskedasticity, and rational scale were checked. It was found that the level of education violated the assumption of homogeneity of variance. This asymmetry was solved in the post-hoc analysis phase by performing a post hoc Games-Howell test instead of a Tukey multiple-comparisons test.

The diastratic variation was examined with a two-way ANOVA and some post-hoc tests: pairwise comparisons t-tests with the Bonferroni correction, Tukey’s tests, and a Games-Howell test. It was decided to indicate the results of the first two tests because, although “Bonferroni has more power when the number of comparisons is small” (Field, 2012, p. 431), Tukey is more reliable with dissimilar sample sizes. The third test was only applied to the variable with heteroskedasticity since it does not assume homogeneity of variance. According to Cohen (1988), for an ANOVA test, 0.1 is considered a small effect, 0.3 assumes a medium effect, and 0.5 indicates a large effect. A value smaller than 0.1 is considered a marginal effect. The significance threshold of 0.05 was maintained. Outliers were removed from the model, but they were included in the description of the frequency.

Results

This segment shows the absolute and relative frequency obtained from the analysis of the corpus PRESEEA-Medellín. The results were compared with the effects documented by Herrera (1995), Olguín (1981), Mendoza (1984), Palacios (1983), and Navarro (2006) to give an idea of the variation in the diatopic parameter. The incidence of social variables on response variables is illustrated in the second part of this section.

Diatopic Variation

The relativizers identified in the sociolinguistic corpus of Medellín significantly exceeded the totals presented by the authors for the other Spanish varieties. However, this is a divergence derived from the collection method and the size of the corpora used, as can be seen in the relative frequency of each token (See Table 4).

Table 4 Relativizers in the Spanish of Medellín, Valencia, Santa Cruz, Mexico, and Santiago de Chile

| Relativizer | Medellín version 1 | Valencia (Venezuela) (Navarro, 2006) | Medellín Version 2 | Santa cruz (Herrera, 1995) | Mexico (low prestige norm) (Mendoza, 1984) | Mexico (high prestige norm) (Palacios, 1983) | Santiago de Chile (high prestige norm) (Olguín, 1981) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | |

| Que | 3681 | 44.80 | 2682 | 65.6 | 5593 | 90.17 | 1434 | 88 | 1349 | 90.2 | 1565 | 86.5 | 3223 | 94.6 |

| Quien | 25 | 0.30 | 75 | 1.83 | 25 | 0.40 | 24 | 1.4 | 14 | 0.9 | 28 | 1.6 | 33 | 0.9 |

| Article cual | 35 | 0.43 | 96 | 2.35 | 35 | 0.56 | 33 | 2.0 | 4 | 0.3 | 43 | 2.4 | 111 | 3.2 |

| Article que | 1912 | 23.27 | 784 | 19.2 | ||||||||||

| Cuyo | 1 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.1 | 12 | 0.3 |

| Donde | 805 | 9.80 | 424 | 10.3 | 477 | 7.69 | 84 | 5.1 | 110 | 7.4 | 133 | 7.4 | 27 | 0.8 |

| Cuando | 1151 | 14.01 | 9 | 0.22 | 21 | 0.34 | 26 | 1.6 | 18 | 1.2 | 19 | 1.0 | - | - |

| Como | 607 | 7.39 | 12 | 0.29 | 51 | 0.82 | 28 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 0.8 | - | - |

| Cuanto | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Total | 8217 | 4085 | 6203 | 1630 | 1495 | 1810 | 3408 | |||||||

| Sample size | 89 | 89 | 89 | 37 | 46 | - | 89 | |||||||

First of all, from the information contained in Table 4, it is evident that the adoption of the theoretical perspective of the NGLE (2009) created a significant discrepancy with the data of the other authors. The unification of que and article que and the elimination of adverbs without antecedents resulted in an increase in the use of relativizer que (46.65 %) and a reduction of cuando and como from 14.03 % and 7.23 % to 0.34 % and 0.83 % respectively. Although the realizations of donde were halved, the relative frequency of this adverb of place was not affected as strongly as that of the other adverbial words. Quien, cuyo and article cual have not perceived important changes. Navarro (2006) also separated que from the compound form el que. If we compare the oral production of Medellín (Version 1) and Valencia, it is observed that Colombian Spanish has a higher use of the complementizer article que than the Venezuelan variety. On the contrary, Valencians prefer the relative pronoun que without any article more regularly.

Some tokens have a similar behavior along the diatopic axis. The selection of que in Medellín (Version 2), for example, fell between the percentage of utterances from Valencia (84.8 %) and the maximum threshold of 94.6 % identified in Santiago. Besides, the values were very close to those of the low prestige norm of Mexico (Mendoza, 1984). These findings are in line with the assiduous tendency of speakers to replace the canonical relativizers with variants containing que. The relative adjective cuyo appeared only once in the Colombian variety consistently with the magnitudes of the other linguistic communities. Its propensity to disappear from the informal and formal registers was already perceived by Alcina and Blecua (1975) more than forty years ago. The relative determiner cuanto is absent from the informal registers in the three communities that have studied the nonstandard norm for Spanish except for Valencia where it is introduced once. It appears a few times (> 0.2 %) in the standard variety of Mexico and Santiago de Chile.

Additional relativizers had rather dissimilar proportions. Medellín exhibits the smallest productivity of pronoun quien and the second most restricted use for relative adverb cuando with values very close to those of the Valencian community. For the first relativizer, Santiago de Chile and Mexico (low prestige norm) double the percentage of occurrences of the Andean city, while Santa Cruz, Mexico (high prestige norm), and Valencia triple or quadruple the Colombian values. Nevertheless, the number of instances is very limited in all varieties (> 1.83 %). Regarding the temporal adverb, the linguistic communities of Mexico (<1.0 %) and Santa Cruz (1.6 %) exceed considerably the oral production of the adverb in Medellín (0.34 %) and Valencia (0.22 %).

Furthermore, the complex relativizer composed by the definite article and cual is underrepresented in the non-standard varieties of Medellín and Mexico. It is slightly more numerous in the standard norm of Santiago and Mexico, in the Spanish community of the Canary Islands (Santa Cruz), and Venezuela (Valencia). Thus, an effect of the diastratic and diatopic parameters cannot be discarded in the production of this relative pronoun. Despite this, more exhaustive and methodologically homogeneous contrastive studies are needed to verify a real correlation between the variables. The adverb donde is the second most frequently repeated relativizer in all the varieties analyzed except for Santiago de Chile. The values are quite uniform even though Medellín has the highest production, only surpassed by Valencia’s. The use of adverb como in the Andean community reveals important diatopic differences only in comparison with the Canary Island, where the modal relativizer is used twice as often, and in parallel with the low prestige norm of Mexico, which has no occurrences.

In summary, it seems evident that the tendency toward the reduction in the use of relative adjectives (cuyo and cuanto) and the increase in the frequency of the unmarked form (que) has been maintained from the 1980s to the present day. Some anaphoric items such as que, cuyo, and cuanto do not exhibit variation due to the diatopic parameter. In contrast, relative adverbs and the relative pronoun quien present some differentiation derived from geographical variation. A more in-depth study is required to accurately delimit the percentage corresponding to the random error and the effect of the explanatory variable. Subsequent section will focus on the diastratic axis of the study; it will show the most relevant data related to the correlation between age, gender, educational level, sex and the frequency of relatives.

Diastratic Variation

Three outliers identified with the Grubbs test were eliminated. The assumptions of independence of observations, normal distribution (central limit theorem), at least interval scale (mean between groups), and homoskedasticity were also verified. The result of the Levene test reported that the error variance for gender (F (1.84) = 0.09, p = .76), generation (F (2.83) = m0.86, p = .42.), and social class (F (2,83) = 2.48, p m= .089) is constant since the results were not significant. The level of education instead presented heteroskedasticity (F (2,83) = 4.55, p = .01) and, consequently, a post hoc Games-Howell test was applied instead of a Tukey multiple comparisons test to account for this variance asymmetry (Howell, 2013). The ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the education level (F (2, 76) = 3.37, p <.05, η2 = 0.08), social class (F (2, 76) = 3.56, p <.05, η2 = 0.08), and the interaction between gender and generation (F (2, 76) = 3.26, p <.05, η2 = 0.079) on the production of relativizers. The Adjusted R-squared showed that the model can explain 17 % of the variation in the response variable. Gender and generation alone did not exceed the designated significance threshold (0.05).

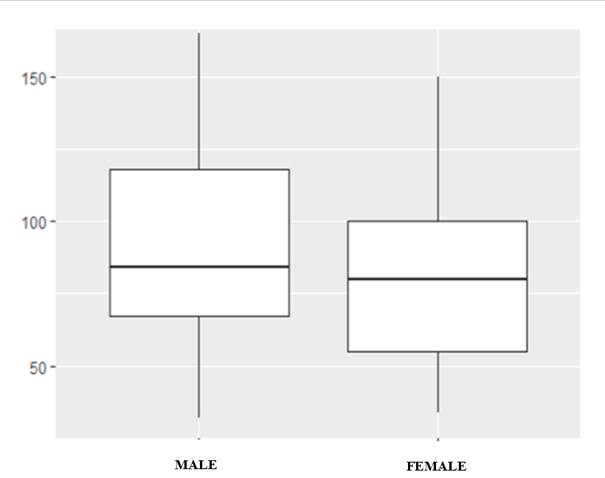

The Effect of Gender

The difference in frequency perceived in men (59.48 % [4888/8217]) and women (40.51 % [3329/8217]) was partly dictated by the lack of symmetry of the corpus (48 men and 41 women). Although, in practice, male participants produced a higher number of relativizers (X̄ = 92.42, SD = 35.12) than women (X̄ = 81.19, SD = 34.0), the ANOVA, the Games-Howell test, and the post-hoc t-tests indicated an absence of significance t (83.67) = 1.5055, p = 0.136. Figure 1 illustrates the overlapping between the data points of both groups. Consequently, it was not possible to reject the null hypothesis according to which both averages are equal. The small effect r = 0.16 also allowed for concluding that gender does not play a predominant role in the number of relativizers.

Additionally, the distribution of the complementizers helps to understand the lack of a statistically significant difference found in the tests. Table 5 shows that que, cuando and article que have very close percentages between the two genders, but the average usage is slightly higher in men for pronouns and in women for the adverb of time.

Table 5 Gender and Proportion of Relativizers (with Outliers)

| Gender | que | el que | cuando | Donde | como | el cual | quien | cuyo | TOT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Freq. | 2229 | 1121 | 577 | 479 | 438 | 32 | 11 | 1 | 4888 |

| % | 45.60% | 22.93% | 11.80% | 9.80% | 8.96% | 0.65% | 0.23% | 0.02% | 100% | |

| X̄ | 46.44 | 23.35 | 12.02 | 9.98 | 9.13 | 0.67 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 101.83 | |

| F | Freq. | 1452 | 791 | 574 | 326 | 169 | 3 | 14 | 3329 | |

| % | 43.62% | 23.76% | 17.24% | 9.79% | 5.08% | 0.09% | 0.42% | 100% | ||

| X̄ | 35.41 | 19.29 | 14.00 | 7.95 | 4.12 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 81.20 | ||

| TOT. | 3681 | 1912 | 1151 | 805 | 607 | 35 | 25 | 1 | 8217 | |

Note: Red indicates the lowest production, yellow the medium one, and green the highest one.

The forms donde and como have a medium rate: there is little difference between the proportions of use of the spatial adverb (higher average for men) and a notable discrepancy regarding the modal relativizer (ratio 2:1) in favor of males. The complementizer constituted by article and cual is preferred by men while quien is chosen more often by women.

The Effect of Age

Regarding the relationship between age and frequency of use, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test showed a significant difference between Generation 1 and Generation 2, t = 2.772, p .05 but none between G1 and G3, t = 1.033, p> .05 or G2 and G3, t = -1.611, p> .05. (R2). The Pairwise comparisons using t-tests and the Games-Howell test, on the other hand, did not reveal any significant pairs. The confidence intervals crossed zero in the last two comparisons, implying that the true difference between their means could be zero (no difference). All comparisons produced insubstantial effects (G1-G2: -0.09; G1-G3: -0.06; G2-G3: 0.03), suggesting that generation change does not have a main role in the production of relativizers.

The ratios of relativizers along the generational axis are maintained for the majority of the variants (see Table 6).

Table 6 Generation and Proportion of Relativizers (with Outliers)

| Generation | que | el que | cuando | donde | como | el cual | quien | cuyo | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 (29) | Freq. | 1042 | 545 | 321 | 242 | 119 | 3 | 5 | 2277 | |

| % | 45.76% | 23.94% | 14.10% | 10.63% | 5.23% | 0.13% | 0.22% | 100% | ||

| X̄ | 35.93 | 18.79 | 11.07 | 8.34 | 4.10 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 78.52 | ||

| G2 (32) | Freq. | 1454 | 789 | 425 | 294 | 321 | 24 | 10 | 1 | 3318 |

| R.F | 43.82% | 23.78% | 12.81% | 8.86% | 9.67% | 0.72% | 0.30% | 0.03% | 100% | |

| X̄ | 45.44 | 24.66 | 13.28 | 9.19 | 10.03 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 103.69 | |

| G3 (28) | Freq. | 1185 | 578 | 405 | 269 | 167 | 8 | 10 | 2622 | |

| % | 45.19% | 22.04% | 15.45% | 10.26% | 6.37% | 0.31% | 0.38% | 100% | ||

| X̄ | 42.32 | 20.64 | 14.46 | 9.61 | 5.96 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 93.64 | ||

Table 6 evidences that que and article que retain primacy in all age groups with a percentage of around 45 %. G1’s mean is the lowest for all complementizers. The second generation, on the contrary, exhibits the highest averages of the sample for the two particles and also for como and article cual. This is probably the cause of the significance found by the Tukey’s test. The low frequency of donde reflects a lower use of relative clauses with a spatial function introduced by the adverb. The divergence mentioned is not semantic but lexical: when the percentages of the meanings of the relative segments were analyzed, it was noted that the trait [+ place] had the highest frequency in the second generation. From this information, it can be deduced that G2 tends to choose more often variants of the adverb donde (que or article que) to denote space.

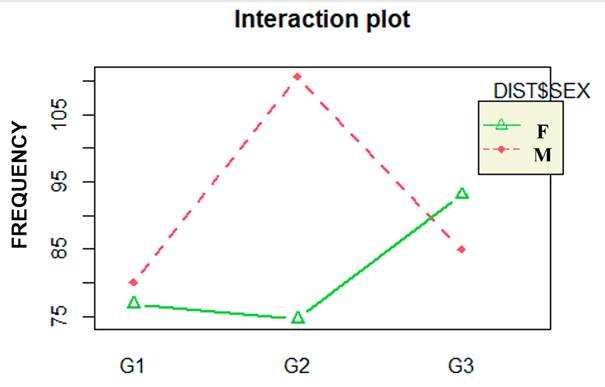

Regarding the interaction between the two predictors described, Figure 2 shows a distinction between males and females in how age affects the frequency of relativizers as the lines are not parallel.

There were fifteen combinations derived from the two social variables. Tukey’s test revealed that the variations between the words produced by the speakers are much greater for men of the second generation (X̄ = 110.56, DS = 27.78) than for women of the same age group (X̄ = 74.57, DS = 31.37). This difference was significant at an alpha level of 0.037. Nonetheless, the size of the effect is insubstantial. Social class, on the contrary, exhibits some levels with a more prominent effect, as is presented in the next segment.

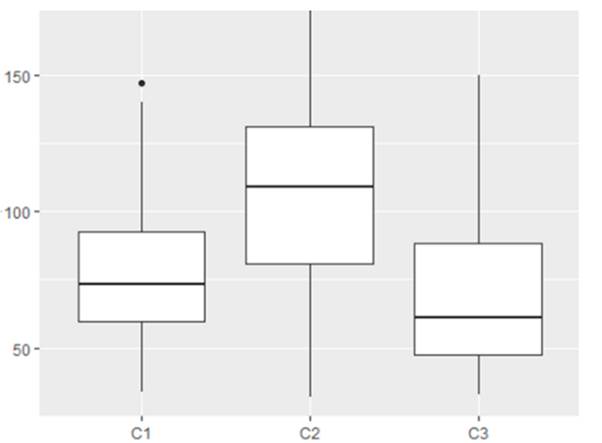

The Effect of Social Class

Social class is one of the significant variables identified by R through ANOVA. Figure 3 shows a notable difference between the average of the second class (X̄ = 103.22, SD = 39.18) and that of the first (X̄ = 78.58, SD = 27.01) and the third class (X̄ = 73.71, SD = 40.95).

The Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni’s correction and Games-Howell’s test found a significant difference only for C1-C2 (p =.0052 and p =.010 respectively). In turn, Tukey’s test did not determine any type of significant divergence: C1 and C2, t = 1.24, p>.05; C1 and C3, t = -0.56, p>.05; and C2 and C3, t = -2.007, p>.05. The effect was small for combinations that include C2, but it was insubstantial for the one in which that level is absent: C1-C2 =-0.14: C1-C3 = 0.02; C2-C3 =0.12.

Regarding the types of relativizers collected in Medellín, the forms que and article que did not propose remarkable differentiation between the three social groups, except that C3 choose them slightly more often than the other complementizers. The average use coincided between C1 and C3 for both constructions while C2 had higher values as seen in Table 7.

Table 7 Social Class and Proportion of Relativizers (with Outliers)

| S. Class | que | el que | cuando | Donde | como | el cual | quien | cuyo | TOT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 (50) | Freq. | 1796 | 984 | 634 | 412 | 369 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 4211 | |||||

| % | 42.65% | 23.37% | 15.06% | 9.78% | 8.76% | 0.14% | 0.21% | 0.02% | 100% | ||||||

| X̄ | 35.92 | 19.68 | 12.68 | 8.24 | 7.38 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 84.22 | ||||||

| C2 (32) | Freq. | 1635 | 795 | 463 | 336 | 220 | 25 | 16 | 3490 | ||||||

| % | 46.85% | 22.78% | 13.27% | 9.63% | 6.30% | 0.72% | 0.46% | 100% | |||||||

| X̄ | 51.09 | 24.84 | 14.47 | 10.5 | 6.88 | 0.78 | 0.5 | 109.06 | |||||||

| C3 (7) | Freq. | 250 | 133 | 54 | 57 | 18 | 4 | 516 | |||||||

| % | 48.45% | 25.78% | 10.47% | 11.05% | 3.49% | 0.78% | 100% | ||||||||

| X̄ | 35.71 | 19 | 7.71 | 8.14 | 2.57 | 0.57 | 73.71 | ||||||||

The adverbs cuando 10.47 % and como 3.49 % appeared less repeatedly in the discourse of the upper-middle class than in that of the other two social groups: C1 15.06 %, C2 13.27 %. The mean of the last class turned out to be much lower in comparison with the values of the other two levels: it maintained a ratio of 1: 1.64 with C1 and 1: 1.87 with C2 for the time relativizer and a ratio of 1:2.87 with C1 and 1: 2.67 with C2 for the adverb of manner. The relativizer donde was the third most repeated element in the second class with a rate of 11.05 %, but it was the fourth in the other two levels: 9.78 % (C1) and 9.63 % (C3). The highest average was observed in the lower-middle social class [10.5] while those of C1 [8.24] and C3 [8.14] were close together (See Table 7). The complex relativizer article cual was selected much more rarely in the first class (0.14 %) than in the second (0.72 %) and third ones (0.75 %). On average, C2 uttered more instances of this word. Finally, there were no occurrences of quien in the upper-middle class while the lower-middle class exhibited t-values higher than those of the lower class.

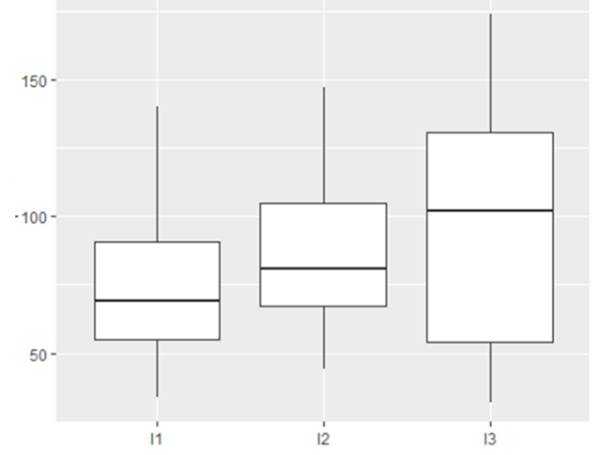

The Effect of Educational Level

With regard to the relationship between the level of study reached by the participant and its use of relativizers, the post hoc Games-Howell test did not identify any significant correlation for the education variable: I1-I2 (p = 0.215); I1-I3 (p = 0.08) and I2 - I3 (p = 0.67). Similar results were obtained from pairwise comparisons using t-tests. All parallels produced insubstantial effects except for the comparison between the first and third educational levels (I1-I2: -0.08; I1-I3: -0.12; I2-I3: -0.04) (See Figure 4).

A look at the distribution of the data (See Figure 4) shows a positive relationship between the number of relativizers produced by individuals and their level of education: as one goes up the scale, the total of anaphoric clauses increases. Table 8 shows that people at the first level of education produced the lowest means, with the exception of the adverb como, which had the highest number. The second level, in turn, presented intermediate values, excluding cuando and the complex relativizer article cual. The most informed group made extensive use of the relative pronoun que, the complex que with definite article, donde and quien; moderate use of cuando and cual; and low use of como. The same distribution was maintained throughout the corpus: que was the most frequent relativizer and quien/cuyo, the least recurrent ones (see Table 8).

Table 8 Level of Education and Proportion of Relativizers (with Outliers)

| Instruction | Que | Art + que | cuando | Donde | como | Art + cual | quien | cuyo | TOT. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 (29) | Freq. | 1036 | 603 | 360 | 236 | 236 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2476 |

| % | 41.84% | 24.35% | 14.54% | 9.53% | 9.53% | 0.04% | 0.12% | 0.04% | 100.00% | |

| X̄ | 35.72 | 20.79 | 12.41 | 8.14 | 8.14 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 85.38 | |

| I2 (29) | Freq. | 1141 | 580 | 384 | 250 | 182 | 17 | 6 | 2560 | |

| % | 44.57% | 22.66% | 15.00% | 9.77% | 7.11% | 0.66% | 0.23% | 100.00% | ||

| X̄ | 39.34 | 20.00 | 13.24 | 8.62 | 6.28 | 0.59 | 0.21 | 88.28 | ||

| I3 (31) | Freq. | 1504 | 729 | 407 | 319 | 189 | 17 | 16 | 3181 | |

| % | 47.28% | 22.92% | 12.79% | 10.03% | 5.94% | 0.53% | 0.50% | 100.00% | ||

| X̄ | 48.52 | 23.52 | 13.13 | 10.29 | 6.10 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 102.61 | ||

| TOT. | 3681 | 1912 | 1151 | 805 | 607 | 35 | 25 | 1 | 8217 | |

Discussion

This variationist study of relativizers in Medellín’s Spanish focused on two main research questions, namely, to what extent do social predictors condition relativizers selection in Medellín? and how do the outcomes of this speech community compare to those of other varieties? Findings reveal that social variables have a minor impact on the frequency of relativizers as the only predictors eliciting a significant effect on the probed linguistic phenomenon are social class and the interaction between gender and age. The significant role of the first variable concurs with findings in Santa Cruz (Herrera, 1995), Valencia (Navarro, 2006), and Caracas (González-Díaz, 2001) although with dissimilar outcomes. The positive linear relationship found by Navarro (2006), González-Díaz (2001), and Herrera (1995) does not apply to Medellín’s context: while in the former cities the sociocultural level (instruction, access to cultural capital) can explain the increase in the number of relativizers (Herrera, 1995) and also the preference of upper-class speakers for canonical pronouns over que galicado (González-Díaz, 2001; Navarro, 2006), in the latter speech community the justification for the lack of positive linearity may be related to the concepts of class aspiration and cross-over pattern.

Some lower-middle-class speakers “in the process of wishing to be associated with a certain class (usually the upper class and upper-middle class) […] will adjust their speech patterns to sound like them” (Patterson & West, 2018, p. 94), but through this attempt, they end up surpassing the normal values of the target class (Labov, 1966, 1972; Trudgill, 1974). It is interesting to note that, effectively, in the corpus PREESEEA-Medellín the upper-middle-class exhibits the minor mean of relativizers (73.71), a piece of evidence that contrast with the linguistic imaginary pursued by the lower-middle class (109.06) and with the results of Santa Cruz de Tenerife (52.83). In addition to these differences, Table 9 shows that the mean in all social classes from Medellín is higher than in Santa Cruz, which might be read as a possible interaction between the diatopic and diastratic variable.

Table 9 Divergence on the Diatopic and Diastratic Axis (Social Class)

| Social Class | Medellín | Santa Cruz | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | Sample size | % | X̄ | Freq. | Sample size | % | X̄ | |

| Lower | 4211 | 50 | 51,2% | 84.22 | 853 | 20 | 52,3% | 42.65 |

| Lower-middle | 3490 | 32 | 42,4% | 109.06 | 460 | 10 | 28,2% | 46 |

| Upper-middle | 516 | 7 | 6,2% | 73.71 | 317 | 6 | 19,4% | 52.83 |

With respect to changes in linguistic use according to age, the absence of a significant effect is consistent with findings in Caracas (Sedano, 1998; González-Díaz, 2001), Valencia (Navarro, 2006), and Santiago de Chile (Olguín, 1981), which implies that the individual’s grammar system remains relatively stable throughout life as far as relativizers are concerned. However, it contrasts with the significant negative correlation identified by Herrera (1995) for Santa Cruz de Tenerife as seen in Table 10.

Table 10 Divergences on the Diatopic and Diastratic Axis (Generation)

| Gen | Age | Medellín | Age | Santa Cruz | Age | Santiago de Chile | ||||||

| Freq. | Sample size | X̄ | Freq. | Sample size | X̄ | Freq. | Sample size | X̄ | ||||

| I | 20-34 | 2277 | 29 | 78.52 | 20-34 | 707 | 14 | 50.50 | 25-35 | 1168 | 26 | 44.92 |

| II | 35-55 | 3318 | 32 | 103.7 | 35-54 | 577 | 13 | 44.38 | 36-55 | 1489 | 42 | 35.45 |

| III | 56+ | 2622 | 28 | 93.64 | 55+ | 346 | 9 | 38.44 | 55+ | 751 | 21 | 35.76 |

Despite the lack of significant results, the second generation of the Colombian dialect seems to make wider use of relative anaphora while the younger generation of the Venezuelan and Chilean varieties shows the greatest numerical representativeness. The lowest values were found within the first generation for Medellín, in the third age group for the Canary Islands and in the second one for Santiago de Chile. It is possible to maintain an interaction between the diastratic and diatopic variables even if it is necessary to test this hypothesis. A methodological weakness in the present study and the research conducted before must be acknowledged: the exclusion of the youngest speakers (below 20 years old) from the investigation may veil the existence of a change in progress in the use of relativizers. This is because, according to sociolinguistic theoretical underpinnings (cf. Labov, 1972; Chambers, 2009; Tagliamonte, 2012; among others), early generations are usually the ones that push the envelope of variation.

In terms of variation due to gender, the lack of statistical significance t (83.67) = 1.5055, p = 0.136 for the Andean speech community is consonant with the findings in Tenerife (Herrera, 1995: men 49.1 %, women 50.9 %) and Santiago de Chile (Olguín, 1981: men 50.9 %, women 49.1 %). These results coincide with the outcomes for Medellín in other linguistic domains (Orozco & Hurtado 2021), suggesting that both women and men have similar sociolinguistic behaviors with regard to more than one linguistic phenomenon. Yet, the ANOVA test determined a significant interaction between gender and age for the second generation. This implies that men ranging from 35 to 55 years old produce more relativizers than women from the same age group. A qualitative analysis of the correctness of the statements could reveal if gender paradox plays a major role in this differentiation.

Finally, the non-existent correlation between the level of education and relativizers proportions found in Medellín cannot be associated with similar studies from other speech communities since Herrera’s (1995) and Olguin’s (1981) did not analyze this predictor. Nevertheless, the evaluation of some related topics (relativizers selection) reveals that Medellín results differ from the conclusions for Valencia (Navarro, 2006) and México City (Powers, 1984). On one hand, Navarro (2006) affirms that education conditions the distribution of the variants article que and article cual and also the presence of resumptive pronouns (negative correlation): “the subjects of the second level of education and especially those of the high socioeconomic stratum restrict the appearance of the duplicated variant” (p. 96, own translation). On the other hand, Powers (1984) demonstrates that the academic background explains considerably the variation in relativizers selection. For example, the preference for the relative pronoun quien at the expense of the complex relativizer article que have a significant positive correlation with the level of education (p = 0.004): level i (17.15 %); level ii (38.46 %), and level iii (38.89 %). The fact that other research proposals about relativizers selection have found significant effects suggests that the relationship between this linguistic item and the educational predictor is more qualitative than quantitative: the level of instruction influences the preference for one variant over another one, but it does not seem to affect the total production of relativizers.

Conclusions

The objectives of the research were to discuss the distribution of use of the relativizers in the linguistic community of Medellín, compare the results with those obtained from other studies, and identify the predictors that affect those proportions. As regards the first purpose, the extension of que to the detriment of the other relativizers is evident. It is worth noting the disappearance of the relative adjectives cuyo and cuanto and the pre-eminence of the complementizer article que in contrast to the more elaborate variant article cual.

Regarding the second objective, the distributions partially resemble those of other varieties of Spanish such as those of Valencia, Santa Cruz, Mexico, and Santiago de Chile. Broadly speaking, que, cuyo, and cuanto show the same behaviors mentioned in the previous paragraph, which is a fact that reveals an overall inclination of Spanish to the extension of the first relative pronoun and the reduction of the other two. All communities have a uniform production of the adverb donde and a slight numerical variation for como, quien, cuando, and article cual: Medellín reports the lowest frequency for the pronoun [+ human] and the complex relativizer. The existence of an effect of the diatopic axis on the selection of complementizers cannot be denied, but it will be necessary to create a statistical model with all the data to ascertain the significance of that variation.

Concerning the third objective, social variables have a minor impact on the frequency of relativizers. The statistical model has distinguished significant relationships between social class and gender-age interaction, which is a fact that would allow for rejecting the null hypothesis. The effects, however, were all small. This means that, although the differences found in the corpus for these variables were not obtained by chance, their ability to explain the variation is not remarkable. In practice, men of the second generation (aged 35-55) produce a greater quantity of relative clauses than women of that age group. Speakers of the lower-middle class and higher education level also have the most representative numbers of the corpus.

Finally, it must be said that the subject of the behaviors of relativizers in Medellín has not been exhausted in this exploratory research. It is required to analyze and compare the usage of relativizers on the basis of their interchangeability in different contexts. In doing so, it is important to consider other relevant predictors such as its syntactic function, the phenomenon of resumption, displacement, emphasis, and the context of production (diaphasic and diamesic variation) of the relative clauses. Comparison with other Colombian varieties and with younger generations would also be relevant to contribute to a deeper understanding of this country’s Spanish. Furthermore, a future study should reckon annotating the corpus PRESEEA-Medellín to increase the level of data reliability.