Introduction

This special issue offers a different perspective on language combinations to that which so often prevails in translation studies literature. Scholars, practitioners, students, and other readers of audiovisual translation (AVT) are invited to invert the Anglocentric lens through which English is customarily viewed as the source or original language, and to explore AVT theory and practice in consideration of English as the target language, i.e., the language of translation.

In the privileged position it holds as the de facto lingua franca worldwide, English has been either the source or pivot language of innumerable translations over the past century, especially insofar as audiovisual texts are concerned. With the arrival of the talkies in the late 1920s, the film industry soon became dominated by Hollywood, propelled in part by the ‘star system’ (Holmes, 2000; McDonald, 2000). This marketing strategy involved a management style by studios that curated and promoted idealistic personae for movie stars that made their films all the more alluring. The ensuing popularity of Hollywood titles led to the establishment of postproduction industries around the globe dedicated to the localisation of imported English-language content. Films were translated into a myriad of target languages, through professional practices such as subtitling and dubbing, which remain popular to this day, as well as multilingual versions (also called MLVs), which are now defunct. According to Chaume (2012, p. 2), the latter fell out of favour due to “the high production costs involved, and their unpopularity with foreign audiences who wanted to see the original actors and actresses on screen rather than their local counterparts”, likely due to the carefully cultivated stardom of these artists mentioned previously and possibly also due to a certain exoticism attributed to the foreign.

In countries where English is not spoken natively, these English-language originals were and continue to be mainstreamed in cinema theatres, on TV channels and, more recently, on streaming platforms. Conversely, in the Anglosphere, non-English-language, or ‘foreign’, content has traditionally been reserved for film festivals and art-house cinemas until recent times. The surge of subscription video-on-demand platforms (SVoDs or streamers)-such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, HBO Max, Disney+, or Hulu-has witnessed a balancing act whereby content in languages such as Spanish, Korean or Turkish, to name but a few, is now mainstreamed alongside English-language originals. Many over-the-top (OTT) platforms have also embraced the creation of their own original content, both in English and in many other languages, turning themselves from distributors into production companies too.

Ahead of the curve as is its wont, Netflix began creating such content that, in the first instance, was “local-for-local” (Brennan, 2018), thereby catering more thoughtfully to their international audiences. In a move from globalisation to glocalisation (Svensson, 2001), this meant that the company created original content in countries where the streamer was operational, for instance, Spanish content in Spain or German content in Germany. Their tactic has generally been to join forces with existing production houses in the host countries so as to co-produce titles availing of local infrastructure.

It is advantageous for an over-the-top (OTT) media service to have boots on the ground and foster local ventures in such a way, with a physical rather than merely cyber presence. Nevertheless, the fact that the initiative or incentive to produce content at a local level did not emanate from Netflix alone, rather, great impetus arose from European Union legislation that entered into force in 2018. Indeed, Article 13, Directive (EU) 2018/1808 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 November 2018 amending Directive 2010/13/ EU, explicitly states that VoD platforms operating in the member states of the EU must thereafter exhibit a portfolio composed of at least 30% European content, whether that involve acquiring distribution rights to said content, (co-)producing it or providing funding to local producers: “Member States shall ensure that media service providers of on-demand audiovisual media services under their jurisdiction secure at least a 30% share of European works in their catalogues and ensure prominence of those works” (Official Journal of the European Union, 2018, n. p.).

Netflix had already recognised the metamorphosis in content origins before the EU legislation entered the fray, having stated in 2017 that they were “quickly approaching an inflection point where English [would no longer] be the primary viewing experience on [the platform]” (Fetner & Sheehan, 2017, n. p.). In the face of their burgeoning non-English catalogue, Netflix seized the opportunity to go beyond their local-for-local offering, and expanded to a “local-for-global” (Brennan, 2018) one. This meant that not only would the company undertake the production of non-English-language titles, but it would also embark on the widespread post-production of these titles, localising them into a symphony of languages, including English.

Bearing in mind that Netflix was now co-producing its own content in EU nations, the above meant the streamer had unfettered distribution rights to that content, which created more incentive to invest in and get creative with localisation practices, in the aim of appealing to a wider number of viewers. A development of this nature would not be as straightforward as localising English-language content into other languages, for which localisation precedents have existed since the invention of cinema, and new complexities have been brought about in workflows in which the language of the original production has ceased to be English. Adding to this, absolute distribution rights have certainly given rise to larger localisation budgets. Taking the example of English-language localisation for Castilian-Spanish series and films, Netflix has proven more likely to dub ‘Netflix original’ content, for which it has exclusive, open-ended distribution rights (Hayes & Bolaños-García-Escribano, 2022, p. 223). The company could, however, have relied solely on the more affordable alternative of subtitling but has decided to invest more into a localisation mode that might captivate more viewers over a longer span of time. Netflix’s zeal for translating non-English materials into a myriad of languages can be interpreted as an attempt to appeal to its largest cohort of viewers at home in the us and in other English-speaking territories. We can speculate that translation efforts have not been altogether altruistic, but a means to maximise returns on its expenditure into European productions.

Netflix’s global localisation, or ‘glocalisation’, strategy has involved different modes of AVT, such as subtitling, dubbing, voiceover, lector dubbing, subtitling for the d/Deaf and the hard of hearing or closed captioning (SDH or CC) and audio description for the blind and the partially sighted (AD). In most cases, the company has adhered to existing conventions in the markets it seeks to attract with these translational practices and produces, for instance, dubs and subs in language varieties such as Castilian-Spanish for Spain and ‘neutral’ Spanish for Latin America, voiceover (also called lektoring) for countries like Poland, and Cantonese dubs for non-English or non-Mandarin content aimed at Hongkongers. Conventions can be observed in the exhibition patterns displayed in any given country, such as in the higher volume of subtitled or dubbed versions available in their territories, depending on the tradition of the country, and in the default preselection of a given mode when both are available. Nevertheless, preferences can be very subjective and differ between viewers on an individual level rather than national level, which, as put forward by Chaume (2012, pp. 7-8) makes it very difficult to continue to distinguish nowadays between dubbing and subtitling countries as has been done in the past. Having said that, it is interesting, from a company’s operational perspective, to identify which are the most common AVT practices in the various countries where they operate because habituation can sway individual preferences towards one AVT mode or another (Nornes, 2007, p. 191).

Known as a disruptor in the industry, and arguably aware of the changes taking place in the viewing habits of the new digital generations, Netflix has gone against the grain on AVT conventions in cases where the company deems that gains are to be made in so doing. A case in point is that of the English-language dubbing industry. Netflix tiptoed into the virtually empty dubbing arena in late 2016 with its English dub of Brazilian series 3% (Pedro Aguilera, 2016-2020) and adopted an aggressive localisation strategy in its English dubbing thereafter. Taking the example of Netflix’s portfolio of Castilian-Spanish live-action fiction alone, for the period between January 2017 (i.e., the dawn of English dubs) and June 2021, 65.9% of the titles available in this category on Netflix in the UK and Ireland were dubbed into English (Hayes & Bolaños-García-Escribano, 2022). Netflix’s English-dubbing endeavours were largely considered brand new when they first launched but this seemingly novel attribute was not entirely accurate. English dubbing had been popularly practised at different moments in time since the inception of the talkies, with European content localised this way in the 1930s and 1950s, Spaghetti Westerns in the 1960s and Kung Fu films in the 1970s (Hayes, 2021). Despite the decline of dubbing for live-action, animation had continued to be dubbed into English across the threshold of this century. Yet, many native anglophones currently subscribed to Netflix had not ever seen these historic dubs of live action or had not paid heed to the technical quality of the dubbing therein. It could also be argued that viewers might not be consciously aware that productions such as anime are dubbed, due to the characters’ mouth flaps being “simplistic and non-language specific” (Hayes, 2023, p. 10).

Netflix’s modern English dubs are divorced from English dubbing precedent, not only in time but in many other respects, including linguistic and technical quality. To a large extent, the present-day dubs are a big improvement on English-dubbing shambles in the past, which had a rather detrimental effect on films by legendary directors like Fellini or Almodóvar. On the other hand, subtitling has been a constant in the localisation of foreign content in this century and the last. Examples date back to the pioneering English subtitles employed on the BBCs broadcasting of Der Student von Prag (The Student of Prague, Arthur Robinson, 1935) in 1938 (Hall, 2016) to Anthony Burgess’s acclaimed English subtitles for Cyrano de Bergerac (Jean-Paul Rappeneau, 1990) in 1990, through to the annually subtitled films showcased at festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, Venice, or Toronto, and into the art-house cinemas in anglophone countries mentioned previously.

Of course, non-fiction is often subtitled on mainstream distributors like national TV channels, to translate foreign reporters on the news or in documentaries. Furthermore, in the age of streaming and social media, subtitles are prolific on networks like YouTube and Instagram, and many of these are typically created via speech-to-text synthesis, with or without human intervention, and, in the case of Instagram, they appear as paint-on subs rather than full subtitles as is conventional in subtitling fiction. As for non-fiction, such content is often subtitled on more mainstream distributors like national TV channels in anglophone countries. However, it must also be acknowledged that there is perhaps a more notable tendency towards using voiceover in these situations, such as for speech by foreign reporters speaking their native language on the news, e.g., on the BBC (Filmer, 2019), or for speakers in documentaries.

Until the advent of streaming platforms, foreign content had seldom been screened on national TV channels or in mainstream cinemas in anglophone countries and a rather negligible number of English speakers were accustomed to consuming subtitled or dubbed versions. This reality has changed dramatically now that streaming platforms have established themselves as prominent if not prime distributors in the entertainment industry. Given the avalanche of media being produced in languages other than English, Netflix conducted research to determine how best to attract native anglophones to this new content. The company surveyed viewers in the us and found that they reported they would not be interested in watching foreign content in general; however, when this perception by subscribers was contrasted with their viewing habits, the company discovered two main facts: that foreign content was actually being consumed more than the questionnaire had indicated and that viewers in the US who had watched the dubbed version of a series proved more likely to finish the series than those viewers who had selected the subtitles instead (Bylykbashi, 2019).

It is worth noting that English dubbed versions of foreign content are defaulted-or pushed-on the platform. The default setting on English dubs could be a tick-the-box exercise for the ‘prominence’ stipulated in the EU directive. It could also be a ruse to distract viewers in the US who had proclaimed their disinterest in non-English content so that they might watch such content and get hooked on it in time before twigging that it is a dub of another language. The ultimate motivating factor behind attracting more American viewers is, of course, to generate more revenue.

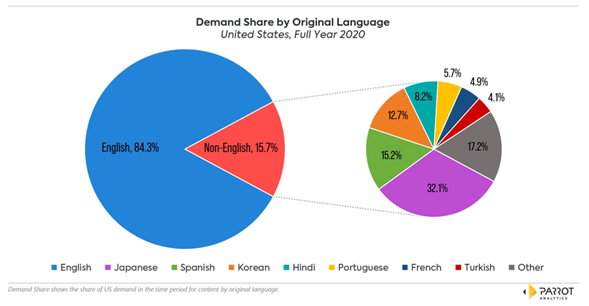

Then Chief Product Officer of Netflix and now (at the time of writing) co-CEO, Greg Peters, has praised the quality of English dubs for increasing viewership of non-English-language content (Collins, 2018). In his keynote speech at Web Summit held in Lisbon, Portugal, in 2018, he stated that “great stories can come from anywhere, and they can travel everywhere, as long as we use technology to get the right story in front of the right person, and make it a great experience” (Netflix, 2018, online). His speech instantly led to media coverage with online article titles like “Netflix’s plan to get everyone watching foreign-language content. Yes, even English-speaking Americans” (Collins, 2018). By 2020, statistics released by Parrot Analytics (2021) revealed that across different distributors in the US -beyond streaming giant Netflix- the demand in the country for non-English content was reflected in 15.7% of content watched, with Japanese, Spanish and Korean contributing most notably to the data, as illustrated in the graphic in Figure 1, which is not exclusively representative of dubbed versions but of localised ones more generally.

A similar study conducted by Patel (2021) confirms that an increasing share of the most popular TV shows and films around the globe are being produced outside the USA, with 27% of the most popular titles in 2021 coming from outside the USA, up from 15% in 2017. One can speculate that diasporic and migrant populations account for a significant portion of this demand, as well as cult followings for the anime genre and the fact of blockbuster titles captivating large audiences, such as in the cases of Spanish series La casa de papel (Money Heist, Álex Pina, 2017-2021) and Oscar-winning Korean film 기생충 (Parasite, Joon-ho, 2019).

Mainstream media in different countries have picked up on the resounding and continual successes of foreign content available on different platforms, often lauding the availability of dubbed versions and giving them credit for these triumphs. On this front, the vast list of Spanish series that have captivated viewers via their English dubs, cited in an article by Adoma (n.d.), the voice actor syndicate of Madrid, Spain, or the South China Morning Post’s (2021) call for more voice actors to meet Netflix’s demand for dubbed versions are clear symptoms of the changes taking place. Might it be serendipitous that through compliance with legislation adopted by countries in the EU, companies such as Netflix springboarded into mass localisation and discovered the unprecedented draw of the likes of English dubs? Or might it be that the streaming giant is forever ahead of the curve, paving its own path that many other streamers then follow? Whichever the case, what is clear is that non-English language films, series, and non-fiction content is thriving among native anglophone audiences, and this is largely due to translations provided in English, whether through dubbing or subtitling.

Wherever English dubbed versions are made available for non-English content, subtitles are also available, whether defaulted or in need of manual selection. Furthermore, non-English content which streaming platforms make available to viewers in anglophone countries and which have not been dubbed invariably come with subtitles. It is therefore safe to say that subtitling remains the most prominent form of localisation for the into-English directionality and the explosion of non-English content on streaming platforms has meant that subtitling is not only more prolific than ever before but it has also brought about a battery of new challenges to transfer content across so many language combinations in a satisfactory manner. Netflix’s Greg Peters, mentioned previously, disclosed that in 2021 the platform “subtitled seven million and dubbed five million run-time minutes” (Marking, 2022), and, according to information released by Netflix, consumption of dubbed programming increased 120% from 2020 to 2021 (Lee, 2022). We can logically calculate that a healthy portion of that dubbing and subtitling was devoted to the robust and growing portfolio of content from languages other than English, requiring translation into English, whether as a final-destination language or stopover, i.e., pivot.

Subtitles are becoming increasingly popular among viewers, especially among a youth demographic. There are multiple explanations for this reality, with the increase in foreign content being only one and not necessarily the most pivotal in steering this demand for subtitles. Indeed, subtitles are often consumed intralingually, meaning in the same language as the audiovisual text itself, whether this be the viewer’s native language or not. One reason viewers tap into the subtitles available in English for an English-language original, for instance, may be for clarity in the sound quality. Not all films have dialogue as unclear as in Christopher Nolan’s movies (Pearson, 2022); however, many are difficult to decipher and taxing on the ears and brain. Dr Ben Byrne, from the RMIT University, Australia, a specialist in sound in digital media, has explained that films were traditionally produced for cinema exhibition and, as such, are made with the expectation of being screened in a room with a surround-sound speakers, a plush acoustic environment, and little or no noise interference (Forsberg, 2023). He further commented on the irony that technological advancements can backfire and whereas actors used to have to project their voices into overhead microphones they now have lapel or portable mics and this can make them complacent in the delivery of their lines and lead to problematically indistinct speech.

Nowadays, individuals often access audiovisual content on devices significantly smaller than a cinema screen, ranging from TV sets to laptop monitors and from tablets to mobile phones. These devices typically have limited speaker projection, with the dwindling size of devices tending to lead to a diminuendo in decibels. Furthermore, nowadays viewers are often nowhere near optimum acoustic environments, with earphones in or headphones on, consuming content in noisy spaces such as public transport. In 2022, Netflix reported that 40% of its subscribers worldwide were using subtitles for all viewing and that 80% would switch on subtitles at least once each month, with both figures surpassing the number of viewers who require subtitles due to hearing loss (Cunningham, 2023).

In a study carried out by YouGov surveying 3,600 participants, the British internet-based market research and data analytics firm found that 61% of viewers in the 18-24 demographic used subtitles vs. 31% of people aged between 25 and 49, 13% for 50 through 65, and 22% for individuals aged 65 and above (Greenwood, 2023). The sound quality of dialogues is sometimes so dire that it can be held responsible for new remote controls (e.g., the Sony Sound Bar) that enable individual viewers to customise their listening experience, such as by amplifying the dialogue tracks so that they stand out from ambient noise. Other reasons a hearing viewer might access subtitles is due to cognitive variation such as hyperactivity impacting attention spans, or due to accents in the film or series that are difficult to attune to, or in aid of learning a foreign language or consolidating the native one, as propelled by the initiative Turn on the Subtitles (https://turnonthesubtitles.org).

Irrespective of the motivation for using subs, distributors must cater to this huge demand. It comes as little surprise that streaming leader Netflix has been setting the trends on subtitling conventions for the past decade. Netflix’s Timed Text Style Guides are offered on open access on the company’s website, available for use by the ilk of partner vendors, e.g., language service providers (LSPs), their freelance translators or anyone interested in subtitling, such as translation academics and subtitlers in training. These guides prescribe technical and linguistic parameters to which subtitlers must adhere in their work. Pedersen (2018, p. 97) noted that Netflix’s early such guidelines were a “one-size-fits-all system”, but that as they are regularly updated, local specificities are being incorporated into many language-specific subtitling guides. Nevertheless, it is undisputable that whether Netflix decides to converge with or diverge from traditional subtitling conventions in any given market, its guides turn to gold and become adopted as the de facto industry standard because many largescale LSPs are clients of the platform, so the guidelines proliferate, and they are also used in many academic centres to train future subtitlers.

It is remarkable to witness the transformation of media (post)production throughout the 2010s and into the 2020s, which has seen English displaced from centre stage as us companies the ilk of Netflix have hedged their bets across a sea of languages. The severity of change over the past decade can be felt in reading previous scholarship:

The international exchange of films and TV productions is becoming increasingly asymmetrical. Onscreen, English is the all-dominant foreign language, and even major speech communities are turned minors in the process. In Europe, only France, Denmark and Sweden have a domestic film production able to keep the United States and other imports below a market share of 80%. Meanwhile, audiences in the United States and the UK are rarely bothered with foreign-language productions. Like people almost all over the planet, they enjoy Anglophone productions. But unlike all others, they do not often enjoy foreign-language productions, whether dubbed or subtitled. (Gottlieb, 2009, p. 21)

Challenges Posed to Studies on English AVT

The invasion of streaming platforms in the field of media distribution and exhibition, together with the boom in foreign-language content on these platforms have created a large amount of work for many professionals in the entertainment industry. Insofar as media localisation is concerned, workload has skyrocketed for practitioners of subtitling (project managers, templators, translators, QCers, etc.) and dubbing (transcribers, translators, script adaptors, voice actors, dubbing directors, dubbing assistants, sound engineers, etc.). In tandem with these developments, scholars in the field of audiovisual translation have been galvanised into researching the novelties brought about by streaming platforms and into updating course curricula to ensure they are keeping abreast of industry practices and best preparing their students for market realities (Bolaños-García-Escribano et al., 2021).

In the specific case of English-language localisation, the above can be a particular challenge for such educators, and the reasons are threefold. On the one hand, the novelty in many of the workflows and processes mean that educators must liaise closely with the industry to have accurate information as to how the processes are evolving, and these details might not be openly available. Although it can be considered that English AVT studies arebeing thrown in the deep-end or experiencing a baptism of fire, they can reap the benefits of relying on earlier research into AVT that focused on other languages as the target language, and chartered practices harking back to VHS tapes through to DVD and Blu-ray discs, to silver-screen cinema, terrestrial and satellite TV channels, and now to streaming services. Although English has not generally featured as a target language in the subs or dubs of these studies, many of the analytical tools remain applicable when the language combinations or directionalities are inverted.

Furthermore, there is a fundamental shift in paradigm at play when one considers distribution directionality and its bearing on research methodology. That is to say that English has predominantly been treated as the source language in translation studies and certainly within studies in audiovisual translation. By trading places and becoming the language of translation, the lens through which English is viewed needs to be adjusted. In Translation-Driven Corpora, Zanettin (2012, pp. 48-51) highlights the need to understand the difference between original and translated texts. For instance, a novel widely distributed in mainstream bookshops in its country of origin might be published by a boutique publisher and marketed differently in a country where the book has been translated. We can draw from this logic that it is difficult to compare English-language originals to English dubs or foreign content with subtitles; however, not necessarily due to questions of distribution.

As streaming platforms are international and offer multilingual content, they can be considered to transcend issues of asymmetry in distribution. Nevertheless, an English-language localised production cannot be equated to an English-language original and must be analysed as a localised version, with many of its characteristics dictated by the original audiovisual text which pertains to another language, culture, and sign system. Although the “scale of postproduction at Netflix is blurring the lines between originals and localised versions and the latter are being treated with the creativity typically reserved for originals” (Hayes & Bolaños-García-Escribano, 2022, p. 229), this creative licence is bringing about trends in the burgeoning category of English-language productions that are the result of translation.

Additionally, the novelty of foreign content for many anglophone viewers has been a double-edged sword as on the one hand it has meant that there are generally few expectations to meet in creating localised versions. On the other hand, however, these expectations are not low, rather they are extraordinarily high because the closest benchmark they have is that of original versions. On occasion, such high standards have led to intolerance, with keyboard warriors lashing out on social media before managing to habituate themselves to English-language localisations and get a sense of their particularities and distinctiveness as a genre in their own right. In response to such complaints about the subtitling of Korean series 오징어 게임 (Squid Game, Hwang Dong-hyuk, 2021-) on Netflix, AVT scholar Orrego-Carmona (2021) safeguarded the AVT discipline and practitioners of audiovisual translation alike by publishing an article in mainstream media to address the concerns of viewers and explain to them the differences between originals and AVT modes like subtitling and dubbing and the restrictions therein. The translation community has also been raising awareness of streaming platforms and language service providers cutting costs and engaging in machine translation with human input only arising at the point of post-editing, i.e., the proofreading stage, which is often carried out by an individual who may have no knowledge of the source language or its cultural nuances and, hence, the poor quality being found in translations.

Content Covered in the Articles of this Issue

The authors of the 12 articles in this issue have approached its theme from an empirical (3), descriptive (7), or theoretical (2) viewpoint, complementing each other so as to paint a clearer picture of the state of the art of audiovisual translation into the English language. Regarding the various professional AVT practices, seven of the articles focus on subtitling and five on dubbing, thereby covering the two dominant modes of AVT. Yet, this special issue heralds more research on AVT into English, dealing with other cognate fields that also form part of the English AVT ecosystem, such ad, SDH, or revoicing practices beyond dubbing such as un-style voiceover or simil sync, to mention a few possible avenues. Concrete themes explored by the authors include pivot-translation practices, the challenges of dealing with the transfer of expletives, diglossic communities and multilingualism, linguistic variation, culturally specific references, argot, cultural identities, interlingually recycled terminology, quality assessment, transcreation, and the use of AVT as a didactic tool in the foreign language classroom.

The source languages revisited throughout the issue are Spanish and Italian, which reflects the fact that the cradle of studies in audiovisual translation finds itself primarily in Spain and Italy. Much scholarly literature in this area is therefore written in or by speakers of Spanish or Italian. The Spanish majority also reflects the Colombian provenance of this journal, as well as realities such as the immense global success of Spanish and Latin American originals hitherto mentioned, which has been possible thanks to English dubs as well as English subtitles. To a lesser extent, other source languages are also discussed, including French, Portuguese, Dutch, German, Russian, and English itself (both intra- and interlingually). Eleven of the articles are written in English and one in Spanish.

The issue opens with three empirical studies. In “On Pivot Templators’ Challenges and Training: Insights from a Survey Study with Subtitlers and Subtitler Trainers,” Hanna Pięta, Susana Valdez, Ester Torres-Simón, and Rita Menezes shed light on a questionnaire concerned with both subtitling practice and training and the challenges faced therein. There were 380 respondents, 100 of whom were pivot templators, 83 of whom also translate from pivot templates, and 75 subtitler trainers. Focusing on the responses provided by the participants, the authors found that Spanish was the most frequent source language of the audiovisual material for which English pivot templates were created and English itself was the second most frequent language of the original material. Nonetheless, findings also revealed that templates were mostly created in English irrespective of the source language spoken in the audiovisual production. Furthermore, most templators creating such English templates speak English as their L2 and so exophonic translation comes into question. Another finding was that training on pivot templating is a rarity despite being widely practised by subtitlers working for SVoDs, and any training provided tends to happen in-house, e.g., from an LSP. The authors respond to the challenges in pivot-template creation by suggesting areas on which to focus when training students or professionals into the practice.

Pięta et al.’s article segues nicely into the next by José Fernando Carrero Martín and Beatriz Reverter Oliver, called “El inglés como lengua pivote en la traducción audiovisual: industria y profesión en España” [English as a Pivot Language in Audiovisual Translation: Industry and Profession in Spain]. These authors surveyed 81 practising translators and interviewed eight more. Almost all respondents had used English-language templates frequently in their work in the preceding five years. Respondents reported that translating from a pivot was increasingly part of their routine and especially in work from SVoDs but also in work for film festivals, with the latter having used pivot translation traditionally, unlike TV channels or the cinema in Spain, where translation directly from the original is more common. The participants in the study routinely translated from pivots for subtitles, dubbing and voiceover scripts, with 74.1% doing so for subs, 65.4% for dubs and 14.8% for voiceover. The article offers insight on a range of AVT practices for different outlets, including SVoDs, language-service providers (LSPs), dubbing studios, videogame studios, TV channels, film festivals and museums. A point worth mentioning from this article is that a high percentage of translators in Spain noted having received education in translation studies (TS) or AVT more specifically. This can be contrasted with the sparsity of TS or AVT tradition at universities or other institutes of higher education in anglophone countries, which might be one reason behind the finding in Pięta et al.’s article that English-language templates are often created by non-native speakers.

The next article, entitled “Exploring Stereotypes and Cultural References in Dubbed TV Comedies in the Spanish-as-a-Foreign-Language Classroom,” focuses on the use of English dubs in the Spanish-language classroom and is co-authored by María del Mar Ogea Pozo, Carla Botella Tejera and Alejandro Bolaños García-Escribano. The authors carried out a perception study with 57 native-anglophone undergraduate students to gauge their understanding and comprehension of certain culturally specific references embedded in the Spanish series Valeria (María López Castaño, 2020-present), often inserted for comic effect. During the experiment, the students viewed the English dub of the series only and were provided with a transcript of the original Spanish for comparison. First, their comprehension of the cultural references was assessed, then the transcription was provided to them and, finally, students were asked to assess the actual translation of the cultural item in the dub and to select their preferred translation from a list of options provided. Using taxonomies from Franco-Aixelà (1996), Pedersen (2011) and Ranzato (2016), the authors then explain the students’ preferences. The participants in the experiment generally preferred conservation techniques, such as specification, but favoured substitution in many cases of obscured meaning. It is also highlighted that the visuals contributed positively to contextualising cultural references and conveying meaning. The article foregrounds the utility of audiovisual translation in the foreign-language classroom, breathing life into linguistic and cultural realities and fostering an acute sense of awareness about the ramifications of using cultural references in an interlingually communicative scenario. Complementary to their experiment, it would be interesting to conduct a similar study with participants that do not speak the language of the original and to compare their preference for different translation strategies.

The descriptive section of this special issue is comprised of seven case studies. The first is authored by Laura Bonella and is called “Language Variation in the Dubbing into English of the Netflix series Baby (2018-2020) and Suburra: Blood on Rome (2017-2020).” The author documents the strategies used in the English dubs of two Italian series on Netflix, both of which were dubbed at VSI Los Angeles. She analyses the portrayal of sociolects in the original and dubbed versions and shows how they are often conveyed via compensation strategies when linguistic asymmetries arise, such as by introducing expletives for colloquial registers or basilects. This article paints a nuanced picture of what is generally termed a ‘standardisation’ strategy, insofar as one American-English accent is used throughout the English dub, but efforts are made elsewhere to differentiate between characters’ speech in lexis, whereas the original resort to both lexis and accent for differentiation.

The following article is by Susana Fernández Gil and its title is “Quality Assessment of the English Subtitles in Five International Award-Winning Colombian Films.” Fernández Gil applies a revised and adapted version of Pedersen’s (2017) far model to the study of the English subtitles of five award-winning Colombian films in order to assess their quality. The films in question, which have all won at least one international award, are La sirga (The Towrope, William Vega, 2012), La playa D.C. (Juan Andrés Arango García, 2012), Tierra en la lengua (Dust on the Tongue, Rubén Mendoza, 2014), La tierra y la sombra (Land and Shade, César Augusto Acevedo, 2015) and Niña errante (Wandering Girl, Rubén Mendoza, 2018). This study reveals how technical parameters in subtitles are generally respected in film festivals, such as in relation to reading speeds and characters per line, but that quality wavers to a notable level when it comes to the transfer of cultural references and idiomacy. The author therefore raises the important question of whether and to what extent subtitlers are assessed on their knowledge of the source language or varieties therein, stating that there might be a disproportionate emphasis on experience in the technicalities of subtitling and being a native speaker of the target language, rather than on the profound knowledge of the source language and culture.

In “Multilingual and Multi-Generational Italian Identity in a Netflix Series: Subtitling Generazione 56k (2021) into English,” authors Marina Manfredi and Chiara Bartolini investigate the rendering of Italian identities in a case study focusing on the English subtitles of the series. They pay special attention to regional or diatopic language varieties and multilingualism. In their study, multilingualism is understood as encompassing geographic dialects (Neapolitan specifically), which is a relevant consideration in the complex linguistic landscape of Italy. They also pay special attention to diachronically marked or generation-specific varieties as well as to colloquialisms, youth speak and taboo language. Within their framework of analysis, linguistic variation is considered insofar as it contributes to characterisation, realism and humour. The authors found in their research of the chosen texts that, in line with existing literature, the subtitles tend towards standardisation of geographically marked language variation and neutralisation of cultural specificities, which leads to a loss of Italianness and sometimes humour. Echoing recent literature noting a change in treatment of taboo language, the authors also found that these subtitles favoured the use of taboo register. Interestingly, another finding is the fact that non-Italian-specific cultural references engaging millennials is generally maintained. This final point might link to Fernández Gil’s speculation about the level of subtitlers’ familiarity with source-language specificities or to a shift in globalised cultural values more broadly, as reflected in the priorities of the subtitler.

In the next article, “Subtitling the Mafia and the Anti-Mafia from Italian into English: An Analysis of Cultural Transfer,” Gabriele Uzzo analyses the techniques employed to convey mafia and anti-mafia lexicon present in the Italian series based in Sicily Vendetta: guerra nell’antimafia (Vendetta: Truth, Lies and the Mafia, Davide Gambino et al., 2021) when subtitled into English. Uzzo highlights that much of the existing literature on this lexicon and its translation deals with English-language originals, therefore focussing on Italo-American English and, to a lesser extent, Italian. The author conducts a quantitative analysis, documenting the number of times given translations have been chosen for the mafia-related references, mafia, mafioso, mafiosi, mafiosa, and mafiose. Then, he proceeds to a qualitative analysis of these data where anomalies arose in translation choices. The scholar explores the fundamental differences between the Italian and English languages as potential contributing factors to some of the translation challenges. The main taxonomy employed in the description of different strategies is that of Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2007). It would be interesting for a follow-on study to compare mafia terminology used in English-language originals with that of the English translation of Italian originals.

In the following article, we move away from feature fiction and into a new territory altogether. In their article entitled “Is Transcreation Another Way of Translating? Subtitling Estrella Damm’s Advertising Campaigns into English,” Montse Corrius and Eva Espasa explore the concept of transcreation in their case study of the English subtitles produced for an ad campaign led by Catalan beer brand Estrella Damm. The authors acknowledge debates surrounding the use of the term ‘transcreation’ in translation studies and how it can be deemed controversial. Yet, they also highlight the industry benefits translators can enjoy when the term is used, such as unimpeded creative licence and higher remuneration for their labour, as well as the fact that the term elevates the perception of translation as a fundamentally creative activity. In the context of their study, the scholars use the term in relation to creative licence in cultural adaptations carried out to reach new audiences. The research focuses on the transcreation of 14 Estrella Damm ads into English for the UK as part of the company’s Mediterráneamente [Mediterraneanly] campaign, which zoned in on the regional origins of the beer. The authors focus on strategies utilised in advertising translation with respect to slogans, cultural references (to food and places) and song lyrics. The authors also conducted two semi-structured interviews: with the creative director of Estrella Damm and with the translator of the ad campaigns from Spanish into English. It is underlined that some of the original ads were recorded in Catalan and others in Spanish but that all ‘source texts’ analysed in the study were Spanish (i.e., some source texts were themselves translations, though culturally and linguistically close to the first source). The findings revealed literal translation in many instances for slogans, transcreation for cultural elements, and non-translation of numerous verbal items such as in the case of song lyrics. Many interesting topics are covered throughout the article including the translation of multilingualism and diglossia or Spanglish. It would be interesting for transcreation such as in this Estrella Damm corpus of subtitles to be compared with transcreation in dubbed ads or in entirely new versions of ads, e.g., with different actors and settings, and in marketing materials such as posters, as compared to videos.

The penultimate article in this case-study section is authored by Noemí Barrera-Rioja, under the title “The Rendering of Foul Language in Spanish-English Subtitling: The Case of El Vecino.” The scholar conducts an exploration on the translation of expletives in the English subtitles of the Spanish series, El Vecino (The Neighbor, by Miguel Esteban & Raúl Navarro, 2019-2021), beginning with a useful walkthrough of terminology pertaining to the topic of profane language, often termed ‘taboo’ in translation literature though not to be confused with culturally taboo topics more broadly. Using Ávila-Cabrera’s (2020) terminology to describe translation techniques, Barrera-Rioja describes the transfer of ‘offensive load’ as being either neutralised, preserved, toned-down, or toned-up (i.e., amped up). The author finds that swearwords have been conveyed in the subtitles in almost 70% of cases, whether accurately or toned up or down, and they have been omitted in the remainder of cases. She then hypothesises why strong language has been kept or not and acknowledges the fact that the series is being shown on Netflix, which has a no-censorship policy. Such is the intent to preserve the taboo register in the subs that the findings show compensation by non-offensive language being ‘toned-up’ as well as auxiliary swearwords being maintained despite their minimal contribution to the plot and their necessarily oral nature vs. the written nature of subtitles. This article demonstrates the value placed on register if the tone of a text is to be faithfully conveyed.

Finally, John D. Sanderson closes the descriptive studies section of this special issue by taking us back to the history of cinema and into the world of Spaghetti, or more generally Euro-Westerns, as well as (American) Westerns, in his article entitled “A Stranger in the Saloon: Lexical Disruption in the English Translation for Euro-Westerns Dubbing.” He rewinds in time and takes us on a round tour of the impact that dubbing has had on both European and North American Westerns, while paying special attention to the unique lexis pertaining to each of the two categories of Western, which he derives from the analysis of a comparable corpus. The first part of the corpus is comprised of 15 American Westerns from the 1940s through 1960s and their translation for dubbing into Spanish. The second half of the corpus is made up of 15 Euro-Westerns from the 1960s and 1970s along with the Spanish dialogue and their English translation for dubbing. Using keyword searches in SketchEngine across the parallel and comparable corpora, Sanderson discovers that a Spanish dubbese arose in the translation of American Westerns, often due to an overreliance on the same translation for terms expressed differently in the original. In turn, terminology used in these Spanish dubbed versions was perpetuated in Euro-Westerns and when these were dubbed into English, the terms were often recycled in English, e.g., via calques or cognates, rather than the translators availing themselves of the existing lexicon from American Westerns. We can consider that the different lexis is reflective of these two types of Westerns being somewhat of a different genre to one another. Alternatively, this cycle of dubbese might more simply be a result of pigeonholing by translators, insofar as they would immerse themselves in the source text so deeply that they became too far removed from appropriately idiomatic and genre-specific lexis in their respective native languages. The notion of the same genre being created on two sides of the Atlantic and perhaps belonging originally to one location more than the other is reminiscent of Uzzo’s discussion on Mafia terminology. We should not underestimate the socio-cultural impact of dubbese and it would be interesting to charter the translation choices for dubbing in the new English dubs of content originating from different languages.

The final section fast-forwards to the English dubs of the late 2010s and early 2020s, venturing into theoretical planes, with both articles investigating the experience of viewers in consideration of the fact that the dubbing mode is new for most of the audience in question. In her contribution entitled “English Dubs: Why Are Viewers Receptive to the Dubbing Mode on Streaming Platforms and to Foreign-Accent Strategies?,” Lydia Hayes interrogates the extent to which native-anglophone viewers may be receptive to the dubbing mode as a novelty and to foreign-accent strategies therein. She explores the evolution of English dubbing and the unique environment in which the English-dubbing industry is currently operating. The Castilian-Spanish dubbing industry is analysed for comparison and the relevance of the (im)maturity of a localisation industry is elucidated inasmuch as it impacts viewer expectations, preferences, and (in)flexibility in professional practices. The author explains a threefold mechanism, called ‘the dubbing trinity’, that viewers engage in when watching dubbed versions. She delves into the habituation of native anglophones to foreign accents in English and then explores the interplay between the aforementioned dubbing trinity and foreign-accent strategies used in English-dubbed versions. The article ends with a series of hypotheses and speculations that seek to explain the current success of English dubbing as a mode of AVT (e.g., in opposition to subtitles) and the acceptance of foreign accents used in English dubbed versions, while at the same time anticipating the future of dubbing practices in English.

The final article, “Engaging English Audiences in the Dubbing Experience: A Matter of Quality or Habituation?,” is authored by Sofía Sánchez-Mompeán, who looks into potential ways to engage English-speaking audiences in the dubbing experience and explores whether the engagement of this specific group comes down to the quality of the dubbed dialogues or to viewer habituation in the consumption of dubbed versions. The author discusses the negative impact that a lack of exposure to the dubbing mode can have on the viewing experience and, therefore, the importance of exposure in leading to acceptance of or willingness to engage with dubbed material. She explores lip-sync, voice performance, and naturalness in wording as key elements that lead to quality in a dubbed version. In relation to these, the author bears in mind comments made by viewers on social media or popular outlets about their experience of dubbed versions. Ultimately, Sánchez-Mompeán states that both high quality and exposure are needed to drive viewer engagement in English dubs, given that there have been lapses noted in lip-sync and given that viewers are not habituated to consuming dubbed versions. This article is a reminder that, despite the noteworthy boom in English-dubbed content, English dubbing is still in its infancy and viewers are particularly immature inasmuch as habituation is concerned.

Concluding Remarks

The remodelling of the production, post-production, distribution and exhibition mediascape has generated the need for more localisation of audiovisual content to be done into English. In turn, this demand has brought about a significant growth in the English-subtitling industry as well as the emergence of a most promising English-dubbing industry. This special issue is home to a collection of articles which add to the existing body of research on English-language AVT, currently in nascent stages and consequently modest in size; yet, gathering notable momentum as demonstrated by the publication of recent articles such as on the topic of dubbing (Hayes, 2021; Sánchez-Mompeán, 2021; Spiteri Miggiani, 2021a, 2021b; Hayes, 2022; Savoldelli & Spiteri Miggiani, 2023; Bruti and Vignozzi, forthcoming), as well as subtitling (Sanders, 2022; Black, 2022; Zeng & Li, 2023). Much scholarship to date has focused on English dubbing, likely due to the novelty of the practice in the industry and for most viewers; however, the contents of this special issue tip in favour of subtitling which is representative of the ubiquity of this particular practice.

When it comes to accessibility studies, most research conducted on areas such as SDH or AD have typically tended to focus on English intralingually, while works on dubbing and subtitling, as previously discussed, have looked at English as the source language of translation. Research into access services in English has traditionally received a fair deal of attention but given the current developments in the sector it would be most interesting to look into the interlingual practices of SDH and AD, to make foreign content accessible to people with sensory disabilities.

Additionally, alternative forms of dubbing into English, such as in videogame localisation, and of subtitling, such as in the case of surtitling and fansubbing, are being regularly practised but are nevertheless somewhat lacking in research. Furthermore, beyond the two dominant modes of AVT, i.e., subtitling and lip-sync dubbing, UN-style voiceover has often been used for translating non-fiction into English, such as for foreign news reports, documentaries, as well as in the arguably pseudo-non-fiction genre of reality tv, and so these are more areas for exploration in future research. The relatively recent advent of lector dubbing in English (Netflix, 2023), as practiced in shows like 피지컬: 100 (Physical: 100, Jang Ho-gi, 2023), a hybrid between lip-sync and the more traditional un-style voiceover in which the two languages can be heard at the same time (Díaz-Cintas & Orero, 2010), lends itself as a novel field of exploration.

It would also be academically enriching to compare localisation practices for international streaming platforms with those for national ones such as, for instance, BBC iPlayer in the UK, RTÉ Player in Ireland, RTVE Play in Spain, Rai Play in Italy and ARD Mediathek in Germany, as well as for international ones such as ARTE, BritBox and IFLIX to name but a few. By studying a wider range of source languages, this would further help to paint the picture of processes currently followed in English AVT, as there is a plethora of European languages being translated but also many Asian languages. Archival research conducted by scholars such as O’Sullivan and Cornu (2019), Alfano (2020) and Mereu Keating (2021) on the historiography of dubbing and subtitling into English, as an informative precedent of what is being done these days, has the potential of shedding light on and informing current industry practices and our understanding thereof. Finally, it would greatly benefit the body of literature on English AVT if more empirical research were undertaken, especially insofar as reception and perception studies with viewer respondents are concerned. This is not least of all because viewers nowadays hold sway over industry practices, given the projection of their voices on social media.

Drawing on the work of some prominent and promising scholars in the field of AVT, this special issue covers a few of the central areas of concern in the novel and dynamic study of dubbing and subtitling into English. A wide range of themes and issues have been discussed from a variety of perspectives, representing some of the many facets in which AVT manifests itself in the Anglosphere and are a testimony to the transforming power of AVT in cultural and media exchanges. The articles herein not only take stock of current practices and supply answers to some crucial questions, they also open up new debates by formulating new questions. We are optimistic that this volume will mark a solid start in the academic study of English-language AVT and will encourage further research that will allow us to charter the territory as practices evolve and the sample size of localised material expands.