Introduction

The film industry is a multi-billion-dollar business providing entertainment to millions of viewers globally. Hundreds of movies are released each year, and the United States and Canada alone released over 700 films per year between 2014 and 2019 (Navarro, 2022) in addition to the thousands of films and series available on streaming platforms such as Netflix, which had over 2000 titles available in the same period (Soda, 2019). However, translation is key to globalization and the international success of any industry.

During Netflix’s fq4 Earnings Call in January 2022, Theodore Sarandos, Co-CEO of Netflix, expressed that “great storytelling from anywhere in the world can entertain the world” (Gupta, 2022, p. 6), and reaching the entire world is only possible through translation. The biggest cinematographic hits such as Joker, Avengers, Squid Game, Money Heist, and many others would not have become global phenomena without their dubbed and subtitled versions, which are the most common translation modalities to broadcast programs in television, cinema and streaming platforms. During the same call, Gregory K. Peters, Netflix’s COO, stated that the streaming platform subtitled seven million run-time minutes and dubbed five million run-time minutes in 2021 (Gupta, 2022), demonstrating a small gap between subtitling and dubbing. However, the company usually dubs into nine languages and offers subtitles in 27 (Goldsmith, 2019), which makes the gap between the two modalities more considerable; and this could be related to the difference in time and money necessary to produce each translation modality.

Cinema was born in Paris with the Lumière brothers, but the biggest muscle in the industry continues to be Hollywood (Nowell-Smith, 2017). Nonetheless, in recent years other territories have presented internationally successful films such as Rome (2018) by Alfonso Cuarón (México), A Fantastic Woman (2017) by Sebastián Lelio (Chile), Embrace of the Serpent (2015) by Ciro Guerra (Colombia), Wild Tales (2014) by Damián Szifron (Argentina), and Parasites (2019) by Bong Joon-Ho (South Korea). On the series side, Netflix has produced several non-English shows that have become global phenomena: Money Heist (Spain), Lupin (France), Elite (Spain), Dark (Germany), Squid Game (South Korea). According to Bela Bajaria, Netflix’s global head of TV, the viewing of non-English language content in the us increased by 71% between 2019 and 2021 (Avila, 2021).

Bigger audiences come with more considerable pressure on the quality of the productions. In this case, English subtitles become one of the barriers in the way to the heart of the English-speaking audiences, as expressed by Bong Joon-Ho, the director of Parasites, through his interpreter, Sharon Choi, during the Golden Globes ceremony of 2020, “Once you overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films” (Bucaria, 2022). Although small countries, such as Colombia, have many other barriers to overcome before reaching international markets, subtitles will also determine the industry’s growth.

Streaming platforms have globalized and revolutionized cinema and television, but this also means there are many critical eyes on their products. For example, there have been several controversies regarding Netflix’s subtitles, one of the more recent was about the translation into Spanish and English of the subtitles of Squid Game, where the fans noticed and complained about the discrepancies between the subtitles and the original audio, demonstrating how important it is for the public to have high-quality subtitles.

Cinematographic Industry in Colombia

In 1922, the first fiction feature film produced in Colombia was María by Máximo Calvo Olmedo, and the following six years are considered to be the Golden Age of the Colombian cinema, with around 14 feature films recorded in the country (Idartes, 2020). One of the most important moments in the history of the country’s cinema was when Victor Gaviria’s Rodrigo D: No futuro (1990) was the first Colombian film to participate in the Cannes Film Festival, and a bigger surprise arrived nine years later when La vendedora de rosas (1998), from the same director, was part of the official selection in Cannes (Correa, 1999). However, it took over 20 years to see another international success of this magnitude when Ciro Guerra’s Embrace of the Serpent made its way to the Oscars in 2016.

The industry is growing steadily. In 2022, there were 194 films released, re-released, or broadcasted in film festivals in Colombia-154 less than in 2019, where 354 films were released (Proimágenes Colombia, 2021). However, this is the effect of the pandemic; the pre-pandemic statistics reveal there was a constant increase in the number of films released and box office sales in the national cinemas (Proimágenes Colombia, 2021). Now Netflix, Prime Video, and HBO are producing original content in the country, and programs like the Colombian Film Commission are working on the international projection of Colombia in the audiovisual market. The objective of this program is the promotion of the country as a destination for international audiovisual production. Thus, translation will play a determining role in all the stages of these processes.

Considering the increasing international recognition of the Colombian film industry, there is an increasing need to assess the quality of the productions to ensure they meet the highest quality standards or find solutions for the problematic areas. As English is one of the most spoken languages in the world and subtitles one of the most used translation modalities in the cinema, this study assesses the quality of the English subtitles of five international award-winning films: La sirga (2012) by William Vega, La playa D. C. (2013) by Juan Andrés Arango, Tierra en la lengua (2014) by Rubén Mendoza, La tierra y la sombra (2015) by César Augusto Acevedo, and Niña errante (2018) by Rubén Mendoza.

The FAR model for the assessment of subtitles proposed by Pedersen (2017) is the tool selected to carry out the analysis since it was designed for interlingual subtitles and uses a penalty score system that will allow determining the adequacy of the subtitles quantitatively. Some adjustments were made to the model to align it with the objective and scope of this research.

Theoretical Framework

This section presents and overview of the translation quality assessment models used in written texts and in subtitling, followed by the description of the FAR model by Pedersen (2017) and how it was adapted to fit the purpose of this paper.

Translation Quality Assessment

The term “quality” has been the topic of discussion in translation studies for several years, and it has been challenging to define, but there is a long history of different approaches. For the translation of written texts, there is the proposal of Reiss (2000), for whom the text operates at a communication level, and therefore, the translation should aim at being functionally equivalent to the source. House (2015), who initially made the proposal in 1971 but presented a reviewed version in 2015, focuses the analysis on the register and genre of both texts. Also, Nord (1997), with the functionalist approach, focuses on the target audience. O’Brien (2012) analyzed eleven quality assessment models and concluded that most of them were based on an error typology. Moreover, organizations such as the International Organization for Standardization and the European Committee for Standardization have drafted norms for the translation process where the qualities and competencies necessary for translating are specified (ISO 17100:2015, EN 15038). However, all these models are designed for written text and do not consider the technical parameters of audiovisual translation. Therefore, they are not suitable for assessing subtitling or other modalities.

Audiovisual translation entails technical restrictions specific to each modality that force translators to modify the texts only to comply with the spatial and temporal restraints imposed by the media they use. Thus, what might be considered an error in the translation of a scientific article might not be an error in a documentary’s interlingual subtitles. For example, in dubbing, the restrictions are related to lip synchronization and isochrony (Chaume, 2005). Likewise, in audio description, the limitation is the time since it is only possible to describe when there is no dialogue (Orero & Vilaró, 2014). Furthermore, for the different subtitling modalities, there is a limit on reading speed and characters per line, among others (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2021). All these elements particular to each translation modality create the necessity of using a quality assessment method designed specifically for each modality.

Subtitles Quality Assessment

Subtitling is part of a superordinate concept: timed text, divided into several categories, subtitling, surtitling, subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing, live subtitles, and cybersubtitling (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2021). Each of these types of subtitles has its own set of limitations, and the guidelines are usually established by the company requesting the service from the translators, making the definition of quality in subtitling more complex.

Defining quality is not the only challenge; designing a model for measuring quality can be even more complicated. In interlingual subtitling, this term can be addressed differently depending on the agents involved in the subtitling process, subtitler, quality controller (QCer), language service provider, researchers, and others (Díaz-Cintas, et al., 2020). Nonetheless, quality is measured every day in translation. In the case of interlingual subtitling, Nikolić (2021) describes the quality assurance processes followed in different companies -where QCers usually check the technical and linguistic aspects of the subtitles against the client’s guidelines- and presents the results of a survey which indicate that the stakeholders in the quality control process do not have significantly different opinions on what are quality subtitles. This is somehow different from what Remael and Robert (2016) found in their survey study on subtitle quality assurance and quality control, which suggested that clients seem to be more focused on the technical requirements than the linguistic ones, and subtitlers had a broader approach and considered every aspect equally (Remael and Robert, 2016).

Guidelines tend to be a quality assessment tool in subtitling; but each company usually creates its own guidelines, and different translators’ associations have also proposed their guidelines. Carroll and Ivarson (1998) proposed the Code of Good Subtitling Practices a couple of decades ago, a short and simple list of principles for subtitle spotting and translation supported by the European Association for Studies in Screen Translation. This association also provides a list of guidelines for each audiovisual translation modality proposed by international translators’ associations such as the Association des Traducteurs/Adaptateurs de l’Audiovisuel (ATAA) or the Asociación de Traducción y Adaptación Audiovisual de España (ATRAE). However, these guidelines are focused on the technical limits and not on assessing the quality of a finalized product. They provide instructions regarding technical restrictions such as character limit, the use of italics and hyphens, and how to treat songs. There is also the Multidimensional Quality Framework (MQM) designed to assess human and machine translation, and it includes over 100 categories for issue types that can be selected depending on the specific type of text to be assessed (Lommel et al., 2014). Nevertheless, it does not include categories related to audiovisual translation.

Within the audiovisual translation models, there is the NER model. Martínez and Romero-Fresco (2015) proposed this model for the quality assessment of live subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing. It includes three severity labels for the errors (minor, standard, and serious) and measures accuracy by subtracting the total number of errors from the total number of words in the respoken subtitles. Then, the result is divided by the total number of words, and this is multiplied by 100 to obtain a number in percentage values. Based on this model, Romero-Fresco and Pöchhacker (2017) developed the NTR model to assess interlingual live subtitles. The NER model is also the basis for the FAR model proposed by Pedersen (2017).

The FAR Model

In 2017, Pedersen proposed this model for assessing translated subtitles, an error-based analysis where the errors are included and classified depending on their impact on the viewer.

FAR stands for the three main areas assessed in the model: functional equivalence, acceptability, and readability. The functional equivalence area includes two types of errors, semantic and stylistic. These errors are related to the transmission of the original meaning or message; and for Pedersen (2017), the adequate form of assessing this is pragmatic equivalence. Acceptability assesses the adherence of the subtitles to the target language norms and is divided into grammar, spelling, and idiomaticity errors. Finally, readability evaluates how easy to read the subtitles are, and it is essentially related to the technical parameters of subtitling. It is divided into the following three categories: segmentation and spotting, punctuation and graphics, and reading speed and line length.

This model uses error labels and a penalty point system by classifying the errors into minor, standard, or serious, with scores ranging from 0.25 to 2 points. It also proposes an approval rate by dividing the error score by the total number of subtitles.

The FAR model was selected to carry out this research due to the broad scope of the error categories and the penalty point system that allows the comparison of the results between the categories of one set of subtitles and several sets, which was the purpose of this study. However, some modifications were made to increase objectivity when classifying the errors and speed up the process in general.

Model Adaptation

The assessment of these subtitles was made to obtain a general perspective of the English subtitle quality in Colombian films with international exposure. However, given the study’s limits, and since the objective was to give an appreciation of a finalized product instead of a deep analysis of the translation errors, the adaptation of the FAR model in this study modified the use of the minor, standard, and serious labels since the author believes classifying each error within these three categories could entail a high degree of subjectivity unless a group of professional translators can reach an agreement on the severity.

The penalty points of the errors in the FAR model depend on their impact on the contract of illusion with the viewer. For Pedersen (2017), the contract of illusion is an agreement the viewer makes when watching subtitled films where they pretend the subtitles are the exact representation of what is being said on screen. However, measuring that impact is not easy. There are some studies on the subject, such as that of Deckert (2021), where the impact of spelling errors in interlingual subtitles was assessed, and it was found that the viewers did not report a negative impact on their enjoyment, comprehension, or cognitive effort. Furthermore, Kruger et al. (2022) conducted an eye-tracking experiment to assess the impact of high reading speeds and concluded that comprehension declined as the reading speed increased.

More research is necessary to reach a consensus regarding the impact of specific errors on the audience. Nonetheless, as presented in the models of Pedersen (2017), Martinez and Romero-Fresco (2015), and other quality assessment systems, not all errors have the same impact; missing a comma or adding a capital letter will not affect the viewer in the same way a semantic error would, but both should be avoided.

After carefully considering the previously mentioned issues, the author decided that it would be more suitable for the study to apply the severity labels to the categories instead of the errors as follows: minor for readability, standard for acceptability, and serious for functional equivalence. This modification recognizes that not all errors have the same impact while decreasing the subjectivity in the error classification. Therefore, the scores are assigned equally to all errors in the category: all readability errors will have a score of 0.25, all acceptability errors 0.5, and all functional equivalence errors 1.

The approval rate will also be obtained as proposed by the FAR model although, as expressed by Pedersen (2018), there is no reference range for this type of measure in interlingual subtitling. The NER model (Martínez & Romero-Fresco, 2015) considers an approval rate of over 98% acceptable, but since the calculation is based on words and not subtitles as the FAR model, they cannot be compared. Therefore, this measure will only be used to compare the films and support the qualitative data.

Method

Films are not only distributed in cinemas; they usually go through a series of screenings in film festivals around the world and are also screened for international award ceremonies such as the Golden Globes or the Oscars. Usually, non-English language films have to be subtitled into English to participate in these festivals and international screenings, which is why for this research, the English subtitles of the films La sirga by William Vega (2012), La playa D.C. by Juan Andrés Arango (2013), Tierra en la lengua by Rubén Mendoza (2014), La tierra y la sombra by César Augusto Acevedo (2015), and Niña errante by Rubén Mendoza (2018) were analyzed.

All these films are dramas developed in a Colombian context; in turn, the language used in the films includes many colloquialisms and cultural references. The five films participated in several national and international film festivals, and each of them won at least one international award. The subtitles analyzed are those included in the official DVD, and these were extracted using Subtitle Edit; the technical information of each set of subtitles was also obtained with this software.

The films used premiered more than five years ago. However, not all films released in Colombia offer an official DVD that can be used for research or are easily accessible. In this case, the objective was to analyze subtitles that were not created by streaming platforms since the practices and processes in those platforms are well known. Thus, in order to extract the subtitles, DVDs were selected. All the DVDs also included French subtitles since, traditionally, France has been an ally of Colombia in film productions, and it hosts one of the most important international film festivals, the Cannes Film Festival. Nonetheless, those were not included in this study.

The linguistic and technical elements of translation and subtitling were considered during the implementation of the adapted FAR model. Assessing the readability area requires establishing the technical norms to be followed. In this case, since it was not possible to obtain the guidelines each translator received, the subtitles were compared against the standards of the industry described by Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2021). Therefore, the maximum characters per line was 42; one-line subtitles are preferred unless it exceeds the character limit per line; lines should follow grammatical and syntactic considerations instead of aesthetic rules; italics should be used for song lyrics, characters off scene, voices through electronic media such as phones and TV, and for inner monologues; hyphens for distinguishing characters speaking at the same time or interrupted dialogue; and the maximum reading speed will be 17 characters per second (cps). That said, having some subtitles over the limit is allowed in most guidelines; therefore, no penalizations were made for exceeding reading speed unless the average is over that limit.

Before including an error in the analysis, the technical restrictions were checked to make sure there was a more suitable translation that fit the parameters used in each film. In addition to the FAR model implementation, other possibly relevant statistics of the subtitles were retrieved with Subtitle Edit: Maximum reading speed, average reading speed, subtitles below 5 cps, maximum characters per line, minimum duration of a subtitle, maximum duration of a subtitle, and number of subtitles above 17 cps. Also, to provide more information that might help identify the source of the errors, there will be a brief description of the experience of the subtitlers that were credited in some films. The following section includes the results of the FAR model assessment followed by descriptive analysis.

Results

This section presents the results of the application of the adapted FAR model, followed by a table presenting technical information for each film individually, with examples of the main errors found. Next, there will be a table comparing the results of all films included in the study. The FAR results include the total number of errors, the total score according to the penalty system (1, 0.5, 0.25), and the approval rate obtained by dividing the total error score by the total number of subtitles. The result is multiplied by 100 and subtracted from 100, thus, obtaining the approval rate.

La sirga (Vega, 2012)

This film is a drama narrating the story of Alicia, who has fled the armed conflict in her village to go live with his uncle and help him build a hostel in the Andes. It was part of the Director’s Fortnight in Cannes 2012 and won the Best Debut Film award at the Havana Film Festival, among other international and national awards.

Table 1 shows that the functional equivalence category had the highest score, which is of concern since this category has the most severe errors, those that might affect the general cohesion and understanding of the film. In addition, it appears the translator had issues understanding some local phrases and expressions; for example, at 00:36:04, three characters are talking about a friend of theirs who is not present to help them with something.

Table 1 FAR Scores for La sirga

| Categories | No. of Errors | Score | Approval Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Equivalence | 12 | 12 | 97.87 % |

| Acceptability | 14 | 7 | 98.76 % |

| Readability | 4 | 1 | 99.83 % |

| Total | 30 | 20 | 96.45 % |

In the subtitles in Table 2, we can see a semantic error with the phrase “A strange child.” In the original audio, “Y que anda raro” is a local expression that, in this context, means that the person is not behaving as usual, something is wrong with them, but it is related to the paranormal event. Instead of referring to this situation with the ill character, the translation repeats the fragment about the strange child. It was considered a functional equivalence error since the original sentence intends to explain why the character is not there to help the others, and omitting this information leaves the absence of the character unexplained, affecting the coherence of the dialogues especially since the next subtitle also has a functional equivalence error. The Spanish sentence “Sí, está enduendado” means to be haunted by an elf, but the English translation repeats the information about the child instead of referring to the character. Since the scene finishes there, the viewer might not understand the dialogue entirely.

Table 2 Functional Equivalence Error in La sirga

| Spanish Audio | English Subtitles |

|---|---|

| Que estaba allá en la carbonera y se le apareció un niño y... Y que anda raro. | He was in the mine, and a child appeared to him... A strange child. |

| Ah, eso es el duende. | It must’ve been the elf! |

| Sí, está enduendado. | Yes, it is strange. |

The acceptability category had the highest number of errors, which were related to the spelling of proper names and some missing verbs and articles (such as the missing article in the sentence “I forgot shovels”), the name Óscar was written without the accent, there is a missing verb in “The only one who does don Julian,” and the name of the lagoon is La Cocha, thus, the article has to be capitalized, which was not the case in the entire film.

This film does not present a challenge regarding technical aspects of subtitling since the dialogues are slow. Table 3 presents some statistics regarding the technical aspects of the file, and it can be said that this film is within the average guidelines of the industry by not exceeding 40 characters per line and maintaining an average reading speed of 12 cps. Furthermore, the minimum time on screen of a subtitle is usually 1 second (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2021), and at least one subtitle was below this measure. However, no penalizations were made for those subtitles since this could be within the guidelines provided to the translators and some companies consider 20 frames acceptable as the minimum duration (for example, Netflix).

La playa D. C. (Arango, 2012)

This film narrates the story of Tomás, an Afrodescendant young man who ran away from the armed conflict on the Pacific coast with his family and arrived in Bogotá, where life is not easy either. It was part of the Cannes Film Festival’s Un Certain Regard, and it won the Best Director award at the Santiago International Film Festival (SANFIC), among other international and national awards.

This film also had many errors in the functional equivalence category and had the lowest approval rate of all films; most issues were related to the translation of cultural references (see Table 4). For example, at 00:36:11, one of the characters is telling the story of a man who was fighting with his wife over a secret she discovered (Table 5).

Table 4 FAR Scores for La playa D.C.

| Category | No. of Errors | Score | Approval Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Equivalence | 27 | 27 | 95 % |

| Acceptability | 37 | 18.5 | 96.58 % |

| Readability | 20 | 5 | 99.08 % |

| Total | 84 | 50.5 | 90.65 % |

Table 5 Functional Equivalence Error in La playa D.C.

| Spanish Audio | English Subtitles |

|---|---|

| Y la mujer no sé cómo se enteró por allá qué significaba ese corte | His wife found out about it, I don’t know how. |

| y casi lo pela. | She almost shaved his head. |

The word “pelar” means “to peel,” but it is also commonly used in slang to replace “kill” (Table 5). However, in this case, it means that the woman was extremely angry with the man and almost got physical with him. The English translation is FAR from the original meaning and creates a different interaction between the characters; something similar to what happened at 00:37:59, where a character gives his opinion on his haircut.

The literal translation for “violento” is “violent,” but here it is slang for “really good” (Table 6). The man thinks his haircut is amazing; however, the translation conveys the opposite. This film, in particular, had a high number of spelling mistakes and punctuation errors, such as the following subtitles: “What’s uo?,” “Go on, tell him waht we decided.”, “You’ve got talent or ypu don’t.”, “Unbelieable!”

Table 6 Functional Equivalence Error in La playa D.C.

| Spanish Audio | English Subtitles |

|---|---|

| Quedó violento. | Real bad. |

This film is also within the industry standards (Table 7), but the minimum duration on screen here is low, with only 16 frames in several subtitles.

Tierra en la lengua (Mendoza, 2014)

This is the story of a man raised in the violence of the Colombian countryside who one day makes a trip with two of his grandchildren to convince them to kill him before a disease does. It won a special mention by the jury and the Best Film award by the Youth Jury in the Pesaro Film Festival, among other international and national awards.

This film had the highest number of errors in total and the lowest approval rate for functional equivalence (Table 8). The approval rate for readability was the lowest of all films, but given the low score for these errors, the total approval rate of the film was not significantly affected; most errors were due to poor segmentation. Something probably related to the result in functional equivalence is the fact that it contains a significantly higher number of cultural references, which is where the translator failed to convey the accurate meaning. For example, at 00:00:45, a woman is describing her feelings for her husband (Table 9).

Table 8 FAR Scores for Tierra en la lengua

| Categories | No. of Errors | Score | Approval Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Equivalence | 36 | 36 | 94.68 % |

| Acceptability | 15 | 7.5 | 98.9 % |

| Readability | 37 | 9.25 | 98.64 % |

| Total | 88 | 52.75 | 92.2 % |

Table 9 Functional Equivalence Error in Tierra en la lengua

| Spanish Audio | English Subtitles |

|---|---|

| Yo creo que a mí me gustaba un tipo que no le temblara la mano | I think I was attracted to a man whose hands didn’t shake. |

The original phrase “que no le temblara la mano” is an expression making reference to a determined, confident man who does not hesitates when making decisions. Unfortunately, the literal translation used in this case does not render the original meaning adequately, affecting the understanding of the sentence. The same issue happens at 00:17:55 when a woman is in a difficult yoga position, and her grandfather sees her and says, “Uy, mamacita, ¿se torció?” In Colombia, it is a local belief that if you have been in the heat or exercising, you should not open the freezer or take a cold shower because your face or body might get paralyzed due to the sudden temperature change; this is called “torcerse.” The grandfather’s comment in the scene is related to this local belief, and it is also a joke due to the intonation of his voice, a joke lost in the English translation of “Honey, you’re all bent out of shape!”

There were also ten missing subtitles in the file, two of which were on-screen text. Regarding readability, the score was affected by poor segmentation, as exemplified in Table 10.

Table 10 Poor Segmentation Examples in Tierra en la lengua

| Subtitle in English | Proposed Version |

|---|---|

| If your grandfather comes, we’ll have to stop. | If your grandfather comes, we’ll have to stop. |

| Jennifer! Miguel! Come say hello to your [grandpa! | Jennifer! Miguel! Come say hello to your grandpa! |

| and shot him in the back of the head. | and shot him in the back of the [head. |

Table 11 presents the technical statistics. The technical aspect of this film follows the tendency of the previous two. It is within the industry parameters regarding line length and reading speed, but the minimum duration on screen is too low (14f). Moreover, when observing the waveform in the subtitling program, it was noticeable that the spotting was not very precise; the out time of many subtitles is over 20 frames late, which would be the reason so many subtitles have reading speeds under 5 cps, and in some occasions, the audio does not match the subtitle on screen due to the late timing. Figure 1 shows the soundwave with the subtitles of a scene. We can see that the boxes do not exactly match the audio. The first subtitle appears six frames after the audio starts. Moreover, subtitles 1, 2, 3, and 4 end more than 6-7 frames after the audio, which affects the synchrony of the subtitles. These issues are not related to reading speed since it is low in all of them.

Table 11 Technical Statistics in Tierra en la lengua

| Number of subtitles | 676 |

| Maximum characters per line | 43 |

| Minimum duration on screen (SS:FF) | 00:14 |

| Maximum duration on screen (SS:FF) | 06:00 |

| Subtitles over 17 cps | 87 |

| Subtitles below 5 cps | 28 |

| Average reading speed (cps) | 12 |

| Maximum reading speed (cps) | 33 |

La tierra y la sombra (Acevedo, 2015)

This film is a drama narrating a fragment of an old man’s life who returns after 17 years to a home he abandoned, given that his only son is ill. He quickly discovers that sugarcane monocrops have destroyed all the farms in the area. It won the Camera d’Or at Cannes and the Le Grand Rail D’Or and Cannes SACD awards during Critics Week, among other international and national awards.

The results in Table 12 indicate that, although the highest number of errors were in the readability category, the category with the highest score was also functional equivalence, with a score of 9. For example, at 01:04:20, one character admires the personality of the other character’s wife (Table 13).

Table 12 FAR Scores: La tierra y la sombra

| Categories | No. Errors | Score | Approval Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Equivalence | 9 | 9 | 98.11% |

| Acceptability | 6 | 3 | 99.37% |

| Readability | 18 | 4.5 | 99.06% |

| Total | 33 | 16.5 | 96.53% |

Table 13 Functional Equivalence Error in La tierra y la sombra

| Spanish Audio | English Subtitles |

|---|---|

| Tu mujer es brava. | Your wife is brave. |

While in the Royal Spanish Academy’s dictionary, the first definition for “bravo” is someone brave, in Colombia, this word is usually connected to being upset or bad-tempered, which is the case in this scene. Another linguistic error was found at 00:04:42, where one character is saying to the other that he arrived really fast from the other city. He says, “Le rindió” in Spanish, which means he arrived faster than expected. However, the English translation says, “You must be exhausted,” which is entirely unrelated to the original expression.

Two subtitles appeared 10 seconds before the actual start of the audio, and the dialogue happening at the moment was lost. This error would severely affect the viewer since it does not have coherence with what was said before. Therefore, the viewer cannot understand that part of the scene. Regarding readability, there were several missing commas and poor segmentation (Table 14).

Table 14 Technical Statistics in La tierra y la sombra

| Number of subtitles | 475 |

| Maximum characters per line | 40 |

| Minimum duration on screen (SS:FF) | 00:18 |

| Maximum duration on screen (SS:FF) | 05:18 |

| Subtitles over 17 cps | 57 |

| Subtitles below 5 cps | 20 |

| Average reading speed (cps) | 12 |

| Maximum reading speed (cps) | 25 |

Overall, the spotting of the subtitles can be significantly improved. The out time of many subtitles was unnecessarily late compared to the audio, and the in time was a couple of frames late sometimes, making the subtitles appear a little bit later than the audio. However, these issues were not included in the score. This film is also within the technical limits of the industry, except for the minimum duration on screen, which is again too low.

Niña errante (Mendoza, 2018)

This film tells the story of Angelita, a young girl who meets her three half-sisters when their father dies. They make a trip to leave Angelita with an aunt while they grieve their father and get to know each other. It won the Golden Wolf award at the Tallin Black Nights Film Festival and the Best Fiction Film award at the Colombian Film Festival New York, among other international and national awards.

This was the film with the highest total approval rate (Table 15). However, there are several errors related to local expressions or cultural elements, which is why the functional equivalence category has the lowest approval rate. One crucial but easily avoidable error was in the pseudonym of a poet. There is a scene where all the girls are listening to a recording from their father, which transcribed says, “Acordáte1 de equis quini,” literally translated would be “Remember X five hundred.” However, it was translated as, “Remember the poet, ‘X Quint’...?”, which is incorrect because X Quint is not the name. X-504 is the correct pseudonym of a Colombian poet named Jaime Jaramillo Escobar and what should be included in the subtitle. The problem may come from the fact that the actor does not say the complete name “ex five hundred and four”; he only says “equis quini,” which is “ex five hund.” Nevertheless, the translator did not do further research to confirm the name, even though the next lines were a poem written by X-504. A quick search on the internet with the poem’s verses would have clarified who the author was (Table 16).

Table 15 FAR Scores in Niña errante

| Categories | No. of Errors | Score | Approval Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Equivalence | 7 | 7 | 98.86 % |

| Acceptability | 4 | 2 | 99.68 % |

| Readability | 9 | 2.25 | 99.64 % |

| Total | 20 | 11.25 | 98.17 % |

Table 16 Technical Statistics in Niña errante

| Number of subtitles | 613 |

| Maximum characters per line | 53 |

| Minimum duration on screen (ss:ff) | 00:14 |

| Maximum duration on screen (ss:ff) | 06:00 |

| Subtitles over 17 cps | 93 |

| Subtitles below 5 cps | 23 |

| Average reading speed (cps) | 12 |

| Maximum reading speed (cps) | 28 |

On the technical side, there were several subtitles with more than 45 characters per line, even one with 49 and another with 53; these were included as errors. Something particular about this film was the use of hyphens. The others used two hyphens at the beginning of the line to indicate that two characters were speaking, which is the standard. However, in this film, only the second line contained a hyphen, but it was consistent throughout the film. Therefore, there were no penalizations since the guidelines could have instructed it.

Translators

All the films included the name of the translators or subtitling company except for Tierra en la lengua. La tierra y la sombra was translated by a French company that specializes in film production and subtitling services in several languages; no individual names appeared. The same translator worked in La sirga, La playa D.C., and Niña errante. This translator has a blog advertising translation services, including a summary of their extensive experience in several translation fields. This blog states that the translator was born in an English-speaking country and has lived in Colombia for more than 15 years. The specialty areas are social sciences and film and television. It was not possible to determine the background education of the translator, but some of the errors found are unusual given the extensive experience in the field.

Overall Quality

Table 17 compares the scores and approval rates for all the films. La playa D.C. was the film with the lowest approval rate, and Niña errante had the highest; all of them were over 90%.

Table 17 FAR Scores and Approval Rate Comparison Between Films

| Film | Total Score | Approval Rate |

|---|---|---|

| La sirga | 20 | 96.45% |

| La playa D.C. | 50.5 | 90.65% |

| Tierra en la lengua | 52.75 | 92.20% |

| La tierra y la sombra | 16.5 | 96.53% |

| Niña errante | 11.25 | 98.17% |

| Total | 151 | 93.62% |

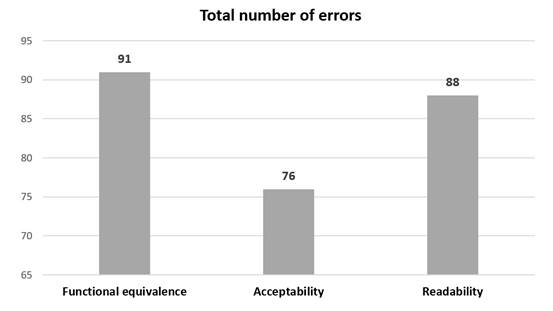

When calculating an approval rate for the films together, the result was 93.62%, showing there is room for improvement in the overall quality. However, Figure 2 presents the total number of errors per category (all films combined) and evidences that the highest number of errors are present in the functional equivalence category, with readability in second place and acceptability in the third.

Functional equivalence: Most errors were related to semantics, especially the mistranslation of cultural references and local expressions. Two of the films had additional or missing subtitles. Even though these errors were included in the functional equivalence category since they considerably affect dialogue cohesion and viewer experience, they could result from the translator not working on the final cut of the film, which occurs sometimes, and it would not be the translator’s responsibility.

On the stylistic side of functional equivalence, only a couple of subtitles seemed to have a register that was too high for the character on screen; but in general, the translations maintained the tone and register of the original.

Acceptability: Even though this category did not have as many errors as functional equivalence, there were still many spelling errors, especially in La playa D. C., which could have been avoided by using a spellchecker either on the subtitling tool or in a text editor. Moreover, there were some grammar issues in the other films related to missing articles or verbs; and in some subtitles, an adaptation instead of the literal translation would have been preferable.

Readability: All the films are within the standard parameters of the subtitling industry described by Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2021) regarding character limit per line and reading speed. However, the segmentation in all films can be improved significantly. For example, many prepositions and conjunctions were left at the end of a line and nouns were separated from adjectives, which might indicate a lack of knowledge of the current subtitling practices.

The spotting of all films can also be improved. The out times were usually late compared to the audio, and on some occasions, the subtitles appeared more than 8 frames after the audio started. However, no spotting errors were included in the assessment since, after an initial viewing of all films with English subtitles, it was noticeable that this issue was repetitive and including them in the scoring would not have enriched the analysis. Moreover, some subtitles were too short. They contained two or three words that could have been merged with the next one to create a more fluid reading experience. There were no penalizations regarding the shot changes since the parameters vary significantly from company to company. The frame gap between subtitles was 2, a standard parameter in subtitling.

The minimum duration of the subtitles is of particular interest since several subtitles appeared on screen for less than a second or even less than 20 frames. The subtitles might have an adequate reading speed; however, as mentioned by Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2021), less than 20 frames might affect the viewer’s ability to read the subtitle completely.

Other Findings

The absence of italics in all films is also interesting. There were scenes with songs, voices heard through phones, or characters out of the scene that were not translated with italics. Nonetheless, this might not be the translator’s responsibility since a different team is in charge of formatting and creating the DVD files for these types of projects. There were no penalizations for this error.

Some films presented inconsistencies in writing words or names, such as Álvaro and Alvaro, Óscar and Oscar, ok and Okay. Since the FAR model does not include a category for inconsistency, these issues were included in readability due to their minimal impact on the viewer.

Discussion

Translating cultural references or cultural-bound terms, for Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2007), is always a challenge for any translator. Several studies discuss the translation strategies for cultural references (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007) or classify the types of cultural references (Zojer, 2011; Malenova, 2015), but the challenge for the translators in these films was the language variety from Colombia. The translators decided to do literal translations of most of the local expressions; however, they did not work in the context. And even though the translator of three films has lived in Colombia for more than 15 years, it was not enough to understand the phraseology. Unfortunately, these errors lowered the quality of the films dramatically since they will probably have more impact on the viewer than a minor reading speed or segmentation error.

Since the film industry in Colombia is just starting to grow and become more international, there are no previous studies on the quality of the English subtitles of Colombian productions. Therefore, this study is an initial assessment that should be replicated with more recent films and other languages to have a broader perspective of the quality of the subtitles. Further studies should help in the detection of repetitive quality issues that would help in the design of improvement plans for the subtitlers, but especially to inform film producers about the relevance of producing high-quality subtitles. Therefore, another field for future research is the quality of the French subtitles, which are almost always included in the DVDs, and it could be valuable to compare the results between languages. Finally, given the characters’ usually slow and short utterances in the films included in this research, it is worth exploring if films with faster and longer dialogues (which would require condensation) also maintain slow reading speeds or if they increase.

Conclusions

In general, the quality of the subtitles was acceptable. The most common parameters of subtitling, such as character limit per line and reading speed, were implemented in all films. However, having the functional equivalence category with the highest number of errors is concerning since those errors potentially change the narrative of the film by modifying the meaning, which directly affects the reception of the film.

It is common in the translation industry to find job opportunities where one of the requirements is to be a native speaker of the target language. However, the results of this research suggest that it might not be enough to correctly translate the colloquialisms and phraseology of a Spanish variant, in this case, the Colombian. The fact that the subtitlers of these films had experience in subtitling, were native speakers of English, and had experience subtitling raises the concern of what qualifications clients should request when hiring a subtitler since the previous parameters were not enough to render correct translations in these films.

The high number of spelling mistakes in La playa D. C. emphasizes the importance of final revisions on the files with external spellcheckers before delivery or with QCers, as it happens in audiovisual translation companies. However, freelancers usually self-revise. Although it was not possible to determine the processes carried out in the subtitling of these films, the spelling errors strongly suggest the revision process was not completed adequately.

In three of the five movies, readability was the category with the highest number of errors, suggesting that subtitlers need more training in the technical aspects of subtitling, such as segmentation and spotting. These results make it relevant to conduct research on the audiovisual translation industry in Colombia to determine if the quality of the subtitles produced in the country is being affected by the low availability of professional subtitlers or by the hiring processes in the producing companies.

Although the objective of this work was to assess the overall quality of the subtitles of Colombian films into English, the results are also relevant to the cinematographic industry. Subtitles are the medium to transmit the film’s dialogues to an international audience and the juries of film festivals. Thus, they should be created with the same rigorousness as the source dialogues to avoid affecting the general audience’s experience and increase the possibilities of a good outcome in film festivals.

Quality is a complex concept in translation in general, and it is difficult to establish the limits between good and bad quality. Thus, this work only considered obvious errors, such as those presented in the examples. The subtitles may have more issues that can be improved regarding fluency and adequacy.

The effect that errors in subtitles has on the audience cannot be measured precisely. However, the subtitles of these five films included many errors in all the categories. With audiences demanding better quality subtitles (as with Squid Game, for example), it is more important than ever to produce subtitles of the best quality.