Introduction

The global success of streaming platforms and the growing demand for localised content have substantially increased the availability of audiovisual products translated into multiple languages. Streaming has brought about the decentralisation of the us film industry and has expanded the reach of non-English language productions around the world. In fact, many of the latest most-watched on-demand series come from non-English markets such as Korea (Squid Game), France (Lupin), or Spain (La Casa de Papel).

Although the import of foreign content into Anglophone territories is not new, the recent bias in favour of English dubbing can be seen as an interesting turnabout. Until now, the practice of dubbing has been associated with the so-called dubbing countries, where viewers are exposed to dubbed versions on a daily basis and where dubbing is a solid and full-grown audiovisual translation (AVT) modality. In the past few years, however, platforms such as Netflix have been actively promoting English-language dubbing as part of their international strategy to try to captivate a bigger audience. As a result, the number of foreign productions dubbed into English as well as the consumption of dubbed material in English-speaking markets, where the dominant transfer mode for non-local shows has usually been subtitling, have risen exponentially (Ampere Analysis, 2021). This AVT modality is now expanding amongst an audience coming from non-dubbing backgrounds and with limited exposure to translated content.

Netflix is nowadays one of the leading subscription video-on-demand (SVoD) platforms worldwide. Its vast catalogue of audiovisual material has led the streaming service to become a dominant global distributor by offering millions of users the possibility to access local and non-local content à la carte. The company’s latest moves clearly evince that it is a staunch advocate of mainstream dubbing (Sánchez-Mompeán, 2021). The platform has been implementing several strategies to promote this practice in historically non-dubbing countries (e.g., Finland, Sweden, or Poland, without much success thus far) and is determined to make it succeed amongst an audience traditionally averse to dubbing. Netflix has spotted a niche in Anglophone markets such as the us. Their own data confirm the apparent triumph of English dubbed versions amongst a major share of us subscribers who decided to watch foreign shows such as Money Heist (La Casa de Papel in the original; Pina, 2017-2021), Dark (bo Odar & Friese, 2017-2020), or The Rain (Kainz & Arthy, 2018-2020) with English dubs instead of with subtitles (Goldsmith, 2019).

Although Netflix’s language settings, which stream the dubbed versions of foreign titles by default, might be partly responsible for such an upward trend, there are grounds to believe that the new generations of viewers are apparently more amenable than ever to watching non-English shows (Roberts, 2021) and gradually consuming more dubbed content (Newbould, 2019). No official figures, however, have been released by the platform so far.

On the downside, dubbing does not seem to be captivating everyone in the public and continues to be a source of controversy in Anglophone territories, where most viewers are being exposed to this AVT mode for the very first time. Dubbed dialogues have received a negative backlash from several users, who have referred to dubbing as “a strangely dislocating and downright weird experience” with characters sounding like “a malfunctioning Alexa” (Watkins, 2021). The fact that target viewers are demanding more quality in dubbed versions has brought pressure to bear on streaming platforms such as Netflix, since high quality holds the key to making their international strategy successful in English-speaking markets.

In this article, the concept of quality is brought to the fore and evaluated as far as viewer engagement is concerned. Negative comments call into question the level of quality of English dubbed versions and, at the same time, pave the way for exploring in more detail the connection between an unfavourable response on the part of the audience and their lack of habituation to this mode (Spiteri Miggiani, 2021b). Due attention is therefore devoted to the relationship between (under)exposure and how dubbing is received and perceived by this “novel” viewership as well as to the impact that an unconsolidated background in English-language dubbing might have on both quality and engagement.

The Dubbing Experience Through the Lens of English Viewers

Viewers exposed to dubbing for the first time will find this practice rather bizarre. The original soundtrack has been removed and replaced by dialogues translated into a different language and reenacted in synchrony by voices not belonging to the on-screen characters. An article published in The Spectator (Watkins, 2021) recently complained about the “dislocating” experience of listening to a French actor such as Omar Sy in the tv drama Lupin (Kay & Uzan, 2021) speaking in a marked American accent while he is strolling across the Seine. The piece points out the difficulty of fitting a language such as English into the fast-pace French mould and concludes by urging English audiences to watch the non-local series with subs instead of with dubs if they really wish to enjoy the authentic and stylish Parisian show.

Netflix, for its part, is convinced that dubbing can increase audience engagement even amongst reluctant users; but its success, or lack thereof, is very often attributed to the quality of the dubbed product. Shoddily dubbed versions of Asian and European films in the past may still linger in the minds of many viewers. Though still on the path to consolidation, English-language dubbing appears to be trying to learn from past mistakes. Greg Peters, chief product officer at Netflix, admitted in an interview that quality dubbing will be the key to attracting a wider and satisfied audience in Anglophone markets (Bylykbashi, 2019); and, as put by Chris Carey, the managing director of one of the most recognisable localisation and media companies in the world (Iyuno-sdi Group), “a good dub has a higher consumer retention, so high engagement”, whereas “a bad dub will lower audience engagement” (O’Falt, 2020). Some of the aspects that could compromise the quality of the dubbed version and, therefore, prove detrimental to engagement are unnatural translated dialogues, overacted performances, and recurring mismatches between the characters’ words and their lip movements (Hayes, 2021; Sánchez-Mompeán, 2021; Spiteri Miggiani, 2021a).

Audience engagement, understood as “the cognitive, emotional, or affective experiences that users have with media content” (Broersma, 2019, p. 1), has always been a major concern in the film industry. Filmmakers and producers seek to keep viewers engaged in the audiovisual content they create and in the story they tell (Piazza et al., 2011). Fresno (2017) explains that in order to facilitate the filmic experience of users, it is paramount that they comprehend what they are watching and get immersed into the plot. This requires, in turn, the receiver’s willingness to take part in the fiction and his/her interest in the audiovisual material, which translate into “a desire to keep watching and discover the twists and turns that await throughout the plot” (p. 14). Even if spectators are fully aware that what they are watching is not real, they can still be transported into the fictional world and become completely absorbed by it thanks to a series of cognitive processes stimulating immersion, namely presence, transportation, character identification, flow, and perceived realism (Raffi, 2020), which can vary according to the fictional content and the spectatorship.

Although there is no empirical evidence to date that dubbing increases audience engagement, research conducted by Palencia Villa (2002) demonstrated that those viewers used to consuming dubbed content were successfully transported into the fictional world and perceived on-screen characters as credibly and authentically as the viewers who watched the original version. Almost two decades later, however, a reception study by Raffi (2020) has shown that language transfer can compromise or partly reduce involvement in the fiction and that original products seem to report a higher degree of immersion than dubbed versions. In her research, the author found that English participants watching an original clip from Game of Thrones (Benioff & Weiss, 2011-2019) managed to reach a higher level of immersion in terms of perceived realism, character identification, enjoyment, and transportation than Italian participants watching the dubbed version of the same clip.

Other studies comparing the impact of dubbing and subtitling on audience engagement have revealed that both modalities are equally effective from a cognitive and evaluative point of view (Wissmath et al., 2009; Perego et al., 2015; Rader et al., 2016; Matamala et al., 2017; Perego et al., 2018). Nevertheless, more recent research by Riniolo and Capuana (2020) has provided evidence on how viewers unaccustomed to consuming dubbed fiction tend to report greater enjoyment when watching the subtitled version of a particular program. Their results indicate that media preference is commonly culture-bound on the grounds that subtitling was selected as the preferred AVT method in primarily English-speaking countries with limited exposure to foreign audiovisual content. These findings are in line with those obtained in an extensive survey conducted by the European Commission (2012) about viewing preferences and with another survey conducted by Netflix (Moore, 2018), in which a clear bias in favour of subtitling was identified amongst mainstream us subscribers. Despite this, the company later admitted a misalignment between viewer behaviours and preferences, as their statistics suggested that dubbing was outpacing subtitling as users’ preferred way to consume non-local productions in this country (Hayes, 2021).

Admittedly, the lack of a deep-rooted subtitling industry in Anglophone markets and the increase in the number of non-local offerings, which were few and far between before the advent of streaming, might be helping to tip the balance in favour of this AVT modality. The positive trend towards dubbing and the fact that Anglophone users appear to be more amenable to this mode given their novice condition as consumers of dubbed content (Hayes, 2021) are opening up a golden opportunity for Netflix to keep developing its international strategy in these territories and to persuade viewers to embrace more dubbed material. However, the company’s intention to stimulate the consumption of English-language dubbing could become sullied by a not-so-favourable reception amongst many of the users who have expressed their dissatisfaction with the poor quality of dubbed versions in terms of synchronisation, naturalness, and performances.

Given the “novel” status of this translation mode, the dubbing experience of English viewers could obviously be affected by multiple challenges posed by the absence of a solid dubbing tradition and consolidated guidelines leading the way in professional practice (Spiteri Miggiani, 2021b). In this light, the aim of the subsequent section is to explore the potential flaws associated with the perceived low quality of the target text as well as the strategies implemented by the streaming giant to satisfy English viewers’ demands and make the most of their dubbing experience.

In Pursuit of Quality Dubbing

Prior to the streaming era and contemporary digital cultures, viewers were deemed as passive consumers of media content, more conformist or simply less demanding. New approaches to viewing experience, however, has led present-day audiences to move from “the traditional role of consumers to an active role of prosumers” (Orrego-Carmona, 2018, p. 322) or, as described by Casarini (2014), “pro-active re-mediators who are highly proficient in program appraisal and directly interact with the shows they watch” (p. 1). On a social level, this interaction surpasses the screen and becomes a powerful tool that brings together subscribers from all over the world while sharing their impressions on social media sites about the original or translated content they consume. The receivers’ standpoint tends to be followed closely by distributors and localisers, who interpret users’ feedback - either positive or negative - as a valuable source of information about their preferences and expectations. Even though in the eyes of spectators the most exposed and vulnerable AVT mode has traditionally been subtitling, owing to the ease with which the source and target dialogues can be compared (Díaz Cintas, 2003), the possibility of switching almost effortlessly between different linguistic versions on SVoD platforms has currently left dubbed products more prone to comparisons and judgements than ever before.

Placing the focus back on English as a target language, it is commonplace to find instances of criticism from lay viewers over translation choices and overall quality. Recent cases in point are the English subs in Squid Game (Dong-hyuk, 2021), accused of changing the meaning and tone of the Korean show, and the English dubs in the Spanish drama Money Heist (Pina, 2017-2021) or in the German series How to sell drugs online (fast) (Käßbohrer & Murmann, 2019-ongoing), accused of lacking naturalness and authenticity. Although such discussions on social networks and fora can contribute to raising awareness about the role and intricacies of audiovisual translation, most complaints arise from non-experts in the field. Despite this, their views are generally taken very seriously and often used as a yardstick to measure quality levels.

The top three most vilified aspects of dubbing by English-speaking target audiences are precisely related to some of the fundamentals of dubbing, namely lip sync, voice performance and natural dialogue, generally perceived as “too dubby”. The so-called “dubby effect” has been described as a type of poorly synchronised dialogue which sounds artificial, distracting, and defies the viewers’ cinematic experience. Since making English-language dubbed content sound less dubby is a priority for streaming platforms such as Netflix (Goldsmith, 2019) and, as acknowledged by the company itself, its subtitles and dubbing “are good but not yet great” (Weiss, 2021), what follows will focus on the most criticised aspects by viewers as a means to identify the potential constraints that might be impairing the quality of dubbed products and reducing English users’ engagement.

Lip Sync

Acceptable lip sync - often used in real practice as an umbrella term to refer to both phonetic synchrony and isochrony - is singled out by Chaume (2007, 2012) as one of the quality standards that should be met in dubbing. In essence, synchronisation makes dubbing work by tricking viewers into believing that audio and image stem from the same source, a phenomenon described as a form of “ventriloquism” by Altman (1980). Phonetic synchrony involves matching the translated dialogue with the articulatory movements of the character’s mouth by mirroring open and closed vowels and bilabial and labio-dental consonants, especially in close-ups and extreme close-ups.

As for isochrony, it concerns the temporal correspondence between the in- and out-times of the source and target dialogues. Complying with the principle of isochrony also means to avoid empty mouth flaps when the character’s lips are moving or to utter sounds while closed, a particularity that Spiteri Miggiani (2021a) prefers to associate with a new type of synchrony named “rhythmic synchrony” (p. 6). According to Chaume (2012), isochrony deficiencies are very often at the bottom of complaints about a bad dubbing, because “this is where the viewer is most likely to notice the fault” (p. 69). Indeed, lip synchronisation (and rhythmic synchrony) adds realism to the diegetic construct and “promotes the strategy of invisible editing” (Magnan-Park, 2018, p. 219), whereas obvious discrepancies between the dialogue track and the image can severely disrupt the receiver’s cinematic experience.

Some of the complaints posted by fans and reported by mainstream media concern unmatched lips in English dubbing, where inaccuracies in the length of the source and target utterances and in the characters’ mouth movements have been perceived quite frequently. Target viewers have been using several adjectives such as annoying, distracting, off-putting, unsettling, upsetting, or simply bad to describe the lip sync of dubbed voices in non-local series and movies, especially those on Netflix (Salvi, 2020; Phillips, 2021; Pollard, 2021). Needless to say, this alleged defective or inadequate lip sync contributes to maximising the dubby effect, which threatens the integrity of the dubbed text and disturbs the viewer’s suspension of disbelief.

Spiteri Miggiani (2021b) explains that the quality of lip synchronisation is sometimes reduced for the sake of naturalness in speech and tempo. On many occasions, prioritising natural-sounding dialogues as well as natural-sounding speed rate implies a less accurate text in terms of phonetic synchrony and isochrony. In fact, English might become more demanding as a target language due to its conciseness and slow pace in comparison with other languages such as French, Spanish, or Italian. A study by Pettorino and Vitagliano (2003) showed that, when dubbing from English into Italian, articulation rates were deliberately modified to abide by lip sync. Voice talents used to decrease pause durations by starting to dub a fraction of time earlier and finishing a fraction later, thus reducing the total number of original pauses by 7% and increasing articulation rates by around one syllable per second in the target version. In terms of translation, condensation techniques were also prioritised. The reverse strategies could thus be needed when dubbing from any of these languages into English to finetune asynchronous mouths and make it easier for viewers to become immersed in the dubbed film without compromising their engagement and enjoyment.

Although the recurrence of imperfectly synchronised mouths can lead spectators to feel disconnected from the audiovisual material and divert their attention away from the storyline (Smith et al., 2014), an absolute match between the lip movements and the words enunciated is almost impossible to achieve and is, in Herbst’s (1997) words, even “unnecessary” to maintain the illusion of lip synchronisation (p. 293). As suggested by Kilborn (1989), Herbst (1997), and Sjöberg (2018), viewers are prepared to accept and compensate instances of slight delays and occasional mismatches, which are seen as a natural and inevitable side effect of the dubbing process. However, it is also true that the lack of regular exposure to dubbing could accentuate this gap and prevent receivers from ignoring the imperfect mismatch between lips and audio. In this case, the inexperience of English viewers when watching dubbed fiction could lead them to pay too much attention to the character’s lip movements, thus remaining more vulnerable to the lie behind dubbing and more sensitive to asynchronous mouths. This (un)conscious eye bias has been explained by the presence (or absence) of the so-called “dubbing effect” (Di Giovanni & Romero-Fresco, 2019; Romero-Fresco, 2020), which will be explored more deeply below.

Voice Performance

Another quality standard to be reached in dubbing is the use of realistic voices and credible performances on the part of dubbing actors (Chaume, 2007, 2012). One of the keys to a favourable dubbed version is precisely the voice cast, which is generally selected according to a number of criteria such as acting skills, professional competence, vocal tessitura, diction, technical and linguistic abilities, and the characters to be dubbed (Pena Torres, 2017). Delving into the Anglophone context, Spiteri Miggiani (2021a) observes that physique, gender, character role, and age tend to be prioritised in the selection of a suitable English voice for a character. Complete unity between the voice we hear and the body we see on screen is of utmost importance for credibility and authenticity. The voice gives a sense of individuality and different nuances to dialogues and characters (Kozloff, 2000). It also plays a foremost role in preserving the identity and personality of characters and needs to meet the expectations of viewers in terms of body-voice correspondence (Bosseaux, 2019). The character’s voice also constitutes a great source of paralinguistic information through intonation, loudness, rhythmicality or tension, adding meaning to the denotative or purely linguistic content of the speaker’s words. In fact, as stated by Kozloff (2000), vocal features are a powerful tool for listeners to judge emotions and recognise emotional states.

A questionnaire distributed to Spanish dubbing actors (Sánchez-Mompeán, 2020a) provided useful input on the most important skills that should be demonstrated when dubbing a character in the studio. Respondents unanimously placed acting skills at the top of the chart, which makes perfect sense considering that making a scripted and read-aloud dialogue sound credible and authentic is much more difficult to achieve if dubbers are not good enough at acting. Along with a satisfactory performance, proficiency in pronunciation and good diction were also identified as fundamental for successful dubbing essentially because a clear and correct pronunciation and diction are necessary skills to produce an intelligible and well-articulated oral dialogue (Wright & Lallo, 2009). Synchronisation also ranked highly for most dubbing actors, even if occasional blemishes in synchrony can be amended by the sound engineer in the last stage of the dubbing process. Mimicking the original actor’s prosodic cues and reflecting the speaker’s attitude were also included as two of the most important factors for dubbing a character successfully.

Issues pertaining to voice and performance were also rated high as the most expected quality standards by lay viewers of Persian dubbing according to a reception study with Iranian audiences (Ameri et al., 2018). Results showed that the consistency of voices through a whole series, the body-voice adherence (Spiteri Miggiani, 2021b), and the accuracy of original pitch and tone in the dubbed version were at the top of the list for participants as the main factors to preserve quality in dubbing and preceded other important aspects such as fluent and natural translations.

When assessing the credibility of voice performances in the Anglophone context, it is not uncommon to find negative comments by users and mainstream media complaining about flat, exaggerated, artificial, unrealistic, and poor deliveries in dubbed dialogues as well as about the notable differences found between some original and dubbed voices in terms of vocal qualities and intonation (Goldsmith, 2019; Salvi, 2020; Pollard, 2021; Watkins, 2021). For instance, an article published in Telegram & Gazette (Phillips, 2021) lauded actress Ludivine Sagnier’s natural voice in the French original version of Lupin while lambasting the dubbing actress’ vocal qualities in the English version, which points once again to the vulnerability of dubbing in the streaming era:

Sagnier’s natural speaking voice, for example, is wonderful: warm, brisk, wholly distinctive. […] Without Sagnier’s actual voice, her first scene in the café renders the character colder, blunter and, in terms of intonation and vibe - hate to say it - far more of a scold.

The above falls in line with Spiteri Miggiani’s (2021a) findings, reporting a general tendency towards flat speech melody and deflated intonation in English dubbing. The author also detects instances of unclear pronunciation and articulation, perhaps motivated by the faster pace adopted in English dubs for synchrony reasons. Such perceptions are at odds with the modulated melody and slower tempo typifying English language but are consistent with the results obtained by Kogan and Reiterer (2021) in their auditory analysis. Drawing on their study, which demonstrates a clear trade-off between pitch and rate in most languages, it may be possible to argue that the faster pace in English dubbing might be preventing the voice talents from resorting to a natural and fluctuated delivery, since these authors’ data reveal that the faster the speech rate in a language, the less pitch is modulated. As a result of this pattern, flatter voice performances instigated by temporal and visual limitations might be maximising the dubby effect and impairing the quality of the English dubbed version.

The choice of accents could also prove detrimental to voice performance and the reception of the dubbed content. Hayes (2021) explains that the absence of proper guidelines has led platforms like Netflix to “experiment” (p. 3) and take arbitrary decisions on the type of accents and language varieties to be used in English dubs, sometimes ending in contrived and overacted performances. As noted by Mereu Keating (2021), the variety of accents and voice talents’ sociolinguistic differences were already open to extensive criticism in the first films dubbed (from Italian) into English, where dubbed voices were accused of sounding “incongruously absurd” (p. 266).

The lack of a long-established and large dubbing industry in Anglophone territories has stunted the growth and development of a skilled and experienced school of dubbers such as the one cultivated in traditionally dubbing countries. Instead, English voice talents have carved out a niche in other professional markets like anime, advertising or animation, which also require a myriad of vocal techniques and specific competences but fairly different from the ones expected in the dubbing practice (Sánchez-Mompeán, 2015). This can obviously bring new challenges to voice performance, firstly, because the number of trained dubbing actors still might not be enough to satisfy the current demand and, secondly, because there is no standard or point of reference against which voice talents can compare their oral delivery (Spiteri Miggiani, 2021b). Likewise, the new viewership will have to set its own tolerance threshold (Spiteri Miggiani, 2021a) to eventually get used to the way dubbed dialogue sounds, which might considerably differ from the “melody” of domestic productions or spontaneous discourse they are familiar with. In this regard, prosodic features become paramount to help to distinguish between what sounds natural within the context of dubbing and what sounds natural in fictional and non-fictional speech (Sánchez-Mompeán, 2020a).

Natural Dialogue

One more requirement for quality dubbing is the translated dialogue itself, which should sound realistic, be plausible, and achieve an acceptable and culture-specific oral register (Chaume, 2007, 2012). In the same way that set designers and scriptwriters bring into being true-to-life settings and dialogues that can trick the audience into believing that what they are watching and hearing looks real, translators/dialogue writers need to produce a translation that sounds natural within the context of dubbing. The language used in dubbing (also known as dubbese) must thus camouflage its prefabricated and written origin while giving the impression of “real realism” (Pérez-González, 2007, p. 7), conveyed by natural and convincing translated dialogues that are “widely accepted and recognised as such by the audience” (Chaume, 2012, p. 81).

Despite the above, dubbese has very often sparked controversy in dubbing countries, even if viewers are habituated and familiarised with dubbed speech. The main reason is that the language of dubbed dialogue imitates some features of spontaneous discourse but also coexists with a very normative and artificial fictional language (Baños-Piñero & Chaume, 2009; Romero-Fresco, 2009), thus widening the gap between dubbed and naturally occurring speech. Nonetheless, it is worth pointing out that naturalness is not necessarily derived from the resemblance between the language used in dubbing and the language used in spoken discourse but rather from “what spectators recognise as the legitimate, acceptable language of audiovisual dialogue”, which is ultimately embraced as “a variety of their language repertoire” (Pavesi et al., 2014, pp. 13-14).

The significant role that the credibility of the dubbed dialogue plays in the enjoyment of the media content has been highlighted by Pavesi et al. (2014), who conclude that viewer enjoyment “is strictly bound to plausibility as audiences become immersed in the fictional representation through realistic characters and settings, but also, we may add, credible dialogues” (p. 11).

Along with asynchronous lips and unrealistic voice performances, English dubbed dialogue has been accused of lacking naturalness with words and expressions that sound too dubby in the target language (Goldsmith, 2019; Miller, 2021). Several comments in the American social forum Quora have wondered why the dubbed versions of foreign-language films and series tend to sound so artificial and unnatural in English (Lavarini, 2020; Writes, 2021; Whitehead, 2021; amongst others). Fans of Money Heist, for instance, have cast doubt on the quality of dubs by complaining about jarring and stilted dialogues. This series is a very interesting case study, for Netflix decided to redub the first two seasons of the Spanish drama in order to cater to viewers’ desires. In other words, redubbing was seen as a problem-solving technique to minimise the perceived dubby effect. Not only did the company hire a new dubbing studio and recruit a different voice cast, but they also retranslated the script for the sake of naturalness and idiomaticity. As shown in Sánchez-Mompeán (2021), the changes introduced in the retranslated version of the series were mainly based on reformulations, omissions, additions, or re-expressions of the previous translated lines with the purpose of making English dialogues sound more natural and truthful. Hints of literal translation were also recurrent in the redubbed script, a strategy curiously associated with low quality when the focus on the literal sense of the words implies rejecting a more functional and meaning-based translation.

Reflecting on the language used in English dubbing, Spiteri Miggiani (2021a, 2021b) points to less standardisation and a bit more over-domestication in an effort to sound as spontaneous as possible in the target language. This clearly diverges from the normative use characteristic in other dubbing cultures, such as Italy or Spain, but reflects the relative freedom Anglophone territories can certainly enjoy in profiling their own dubbese. Spiteri Miggiani (2021a) explains that English-language dubbing might “choose to distance itself by seeking customised strategies, while being aware of the norms that usually govern dubbing elsewhere” (p. 151). Public reception and engagement with the dubbed fiction could facilitate the gradual development of its personality by striking a balance between quality assurance and the constraints imposed by the mode itself. But, most importantly, the audience must end up accepting the way dubbing sounds and be ready to compromise with this “new” naturalness within the context of dubbing, which despite imitating spontaneous-like dialogue will inevitably stem from a pre-planned and prefabricated source.

In sum, the dubby effect perceived by several English users might be reinforced by the presence of potential mismatches between the character’s lips and the audio and between unrealistic deliveries and unnatural translations. Due to the importance of viewers feedback and the commitment of streaming services like Netflix to improve their subscribers’ immersive experience in the (dubbed) content they consume, several strategies are being put into effect to guarantee high-quality levels in English dubs (Sánchez-Mompeán, 2021).

In terms of production, the company is expanding its physical presence transnationally, which means that it now has production facilities in several countries around the globe. It has also optimised both its infrastructure by creating a separate division focused exclusively on dubbing innovation and its network of professionals. In fact, Netflix has added a number of professional roles to the dubbing process such as the Director of International Dubbing, the Creative Dubbing Supervisor, and the Creative Manager of English Dubbing. Their tasks include supervising the recording and mixing sessions, preparing guideline documentation for localisation partners, collaborating with dubbing studios, and providing casting notes, preserving the creative intent of filmmakers throughout languages, and ensuring consistency between the different stages of the dubbing process, amongst others. The company is also investing in the centralisation of work by drawing up practical guidelines and templates to help practitioners deal with translation and recording issues. Quality control processes are also in force to guarantee that the company’s standards are met across different languages.

The deliberate efforts made by Netflix to assess and enhance the quality of English dubbed versions could prove insufficient as long as audiences do not fully familiarise themselves with the dubbing mode. Although there is little doubt that poor quality certainly put viewers off the dubbed product, the novel profile of English-speaking users as dubbing consumers and their lack of exposure to this AVT practice could also exert a negative impact on viewer response and on their immersive experience. Against this background, as will be discussed in the next section, the dislike of many English viewers towards dubbing might not necessarily be based solely on quality reasons but also on their lower threshold of tolerance as compared to more accustomed audiences.

In Pursuit of Spectatorial Comfort

As acknowledged by Debra Chinn, Netflix’s Head of International Dubbing, the company’s intention is to create a new audience in Anglophone territories, one that is potentially more lenient towards dubbing (Goldsmith, 2019). Continuous and long-term exposure to dubbed content might be an essential step in attaining this goal. As a matter of fact, viewers play a significant role in making dubbing work. Evidence shows that in traditionally dubbing countries dubbing works not only because it complies with a number of conventions that make it succeed, but also because viewers become immersed in the fictional world by activating several cognitive processes that make it work. These could certainly contribute to minimising the dubby effect (in terms of lip-sync, realistic performances and natural dialogue) while allowing for extra spectatorial comfort.

One of these processes is related to gaze behaviour, according to Di Giovanni and Romero-Fresco (2019) and Romero-Fresco (2020), who discovered the existence of a dubbing effect, that is, an unconscious eye movement performed by viewers accustomed to dubbing that leads them to accommodate their eyes and direct their gaze to those parts of the screen that can preserve their cinematic illusion and help them forget the “lie” behind dubbing. Spanish participants in the experimental study spent 95% of time looking at the eyes and 5% looking at the mouths when watching the dubbed version of a scene from Casablanca (Curtiz, 1942), whereas English participants watching the same clip in the original version spent 76% of the time looking at the eyes and 24% looking at the mouths. This “prevails over the natural way in which they [dubbing audiences] watch original films and real-life scenes” (Romero-Fresco, 2020, p. 17), confirmed by the viewing pattern of the Spanish group watching a scene from an original Spanish (76 % on eyes and 24% on mouths). It could then be argued that viewers usually exposed to dubbed products have developed a particular attention bias by habit and unconsciously so as to avoid being distracted by occasional mismatches between the words uttered by the characters and their lip movements.

Another process activated by viewers to make dubbing work is the suspension of disbelief, a notion first used by the literary critic Samuel T. Coleridge (1817) to explain the way readers can become immersed in the fictional universe of a book and accept the parallel world created in the story. This could help spectators disregard those instances of unnatural delivery both from a linguistic and prosodic point of view. The suspension of linguistic disbelief refers to “the process that allows the dubbing audience to turn a deaf ear to the possible unnaturalness of the dubbed script while enjoying the cinematic experience” (Romero-Fresco, 2009, pp. 68-69). The author explains that the audience does not compare what they are hearing to what they would hear in a similar real-life conversation but to “their memory of that sound”, determined by what they are used to hearing in other dubbed products. The more accustomed viewers are to this practice, the easier it is for them to preserve their cinematic illusion (Díaz Cintas, 2018). Due to the fact that their threshold of permissiveness is necessarily raised to enjoy and engage with the dubbed material, their degree of tolerance to potential inconsistencies, including the potential unnaturalness of the translated dialogue, is also higher.

By taking this idea a step forward, it could be assumed that viewers could also disregard whether or not the prosodic delivery adopted by dubbing actors in their performances can be equated with that of naturally occurring speech. The suspension of prosodic disbelief involves “accepting that how onscreen characters say what they say may not necessarily sound as they would sound in a similar real-life situation, but as on-screen characters usually sound in dubbed products” (Sánchez-Mompeán, 2020b, p. 296). Whilst watching dubbed content, spectators tend to associate the way characters speak within the dubbing context with their memory of the prosodic patterns recurrent in other dubbed dialogues rather than with the way spontaneous speech really sounds. In the pursuit of spectatorial comfort, they necessarily turn a deaf ear to the potential unauthenticity of dubbing voices and prosodic delivery (e.g., intonation, speed rate, loudness, rhythm, or tension). Once again, the more accustomed viewers are to “the melody of dubbing”, the easier it will be for them to preserve their cinematic illusion and enjoy the fiction.

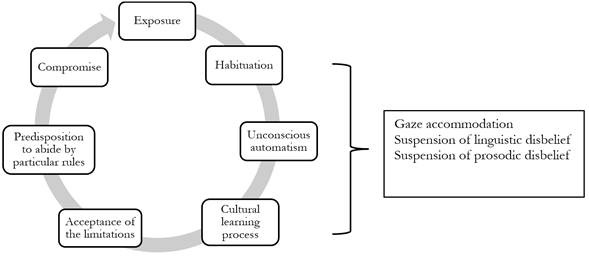

Although, as discussed above, mismatches between sound and image could be disregarded thanks to the dubbing effect, the unnaturalness of the translated dialogue could be reduced thanks to the suspension of linguistic disbelief, and unrealistic voice performances could be attenuated thanks to the suspension of prosodic disbelief, there are obviously other important factors that can determine audience response and wield a direct influence upon their enjoyment and engagement with the dubbed fiction (see Figure 1).

The lack of exposure of Anglophone viewers and, by extension, their lack of habituation and inexperience as consumers of dubbed content might leave them more vulnerable to the uncanniness of dubbing and less open to naturally engage with this mode, an opinion also held by Spiteri Miggiani (2021b). On the contrary, viewers accustomed to dubbing and exposed to it from an early age tend to find it easier to suspend (linguistic and prosodic) disbelief while unconsciously accommodating their gaze for the sake of enjoyment in the same way as they familiarise themselves with the filmic experience (Romero-Fresco, 2020). Even if dubbese is a type of prefabricated language and ordinary people do not really speak like dubbing actors (Whitman-Linsen, 1992), they seem to imagine that they do in the same way that they try to imagine that what is happening on screen could be perfectly real. Once they have internalised the natural processes activated to engage with the dubbed fiction as an intrinsic part of their cultural learning process (Garncarz, 2004), they are more willing to accept the limitations of the medium itself (Chaume, 2013), are more predisposed to abide by the rules of this practice, and feel ready to compromise with the dubbed fiction to help preserve their cinematic illusion.

These processes contribute to spectatorial comfort in dubbing but cannot be held fully accountable for audience engagement and satisfaction in Anglophone territories. It is true that the lack of exposure and habituation of many English-speaking viewers increases their scepticism about dubbing, but quality also plays a fundamental part in this equation (Spiteri Miggiani, 2021a). The aim is to find the right balance between the aforementioned processes and a dubbed product with enough quality to make it easier for viewers to habituate to this AVT mode and be more lenient towards it. Although, by tradition, English-speaking audiences have been the least willing to consume non-local content and the least tolerant to embrace dubbing (Rowe, 1960; O’Halloran, 2020), nowadays English viewers are potentially more amenable to new practices and formats (Hayes, 2021) - certainly a step in the right direction to eventually become accustomed to and accept English dubs.

Conclusions

Streaming platforms have enjoyed a rapturous international reception since they landed in our mediascape, bringing with them a huge demand for translation services and, in some cases, defying established norms and conventions. The rise in dubbed content consumption in non-dubbing countries is a direct consequence of this changing global industry, where users are being given the chance to access more foreign fiction than ever before. Platforms like Netflix are investing heavily in dubbing and making inroads into the Anglophone market, traditionally less amenable to consuming translated material in general and dubbed content in particular. Determined to shape viewing habits and engage novel users in the dubbing experience, this strategy comes with more openness to listening to consumers’ needs and expectations and an increasing willingness to offer high-quality English dubs. Nonetheless, despite the efforts put into drawing in a wider and more satisfied audience in these territories, an unfavourable response on the part of the general public on social networks and fora and reported in the press has called into question the quality of English-language dubbed versions and the possibility of consolidating a dubbing industry in Anglophone countries.

Taking English end users’ reactions and comments about dubbed products as a starting point, this paper has addressed the relationship between quality and engagement by focusing on lip sync, voice performance, and natural translated dialogues, generally disapproved and perceived as too dubby by the public. These constraints, accentuated by the lack of a solid professional industry and dubbing tradition (Spiteri Miggiani, 2021b), exert a negative impact on the quality of the final version and stand in the way of full audience engagement.

Although quality plays a foremost role in eliciting a positive response from viewers, habituation can also be regarded as a determining factor in how they engage with and become immersed in the dubbed fiction (Spiteri Miggiani, 2021a, 2021b). By activating several cognitive processes stimulated by exposure to the dubbing mode, end users might gradually adopt a more lenient approach while raising their threshold of tolerance towards the dubbing environment. Engaging is thus a matter of both quality and habituation, which can be seen as two interrelated forces working together in favour of enjoyment and spectatorial comfort and which are essential to minimise the dubby effect perceived in dubbed versions.

Whilst this article tackles important issues relating to audience engagement and their expectations as novel consumers of dubbed content, it would be interesting to delve further into the rationale behind viewer complaints and the interplay between users’ age and reactions towards this AVT modality. Reception studies could contribute to a deeper understanding of English viewers’ preferences and real performance and how these affect their engagement with the dubbed fiction. This paper also has practical implications for professional development to attract a target audience more open to foreign content and more predisposed to dubbing. Creating a high-quality product in terms of synchronisation, delivery, and translation is obviously necessary to engage and satisfy spectators, but higher exposure and habituation can also hold the key to making English users welcome dubbing more positively and enjoy a similar experience to original viewers.