1. Introduction

Reflecting on and discussing the method of scientific research is always necessary, even if we often have clarity on what, how, where, and why we are researching, since the subjects and processes we study in the humanities and social sciences are in constant trans-temporal, trans-scalar, and trans-territorial movement. By "method" we refer to the research trajectory undertaken since the definition of the topic and object of study, its objectives, goals, theoretical-conceptual orientation, and research techniques.

Therefore, it is a temporal and relational process because we usually do not research alone: we learn and teach through social relationships with others who are directly and indirectly involved in each movement, even in individualized research such as master's and doctoral studies. We thus consider the method as a relational and power-related issue that involves a multidimensionality of political, ideological, cultural, economic, and environmental questions.

Comprehending life and its territorialization is not a simple or quick task. It seems, in fact, that the complexity of life is quantum-gravitational, starting from the intrinsic relationship of particles-atoms-molecules-cells, which happens through the interaction of protons and electrons exchanging photons. These photons, in turn, mediate electromagnetic interactions between particles and generate energy to sustain the universal unity of everything that exists within the solar system-stars-galaxies-galaxy clusters. Gravity and the quantum field mutually "pull" each other, thus avoiding the collapse of our natural-cosmological-social life (Cox & Forshaw, 2016). Therefore, life is extremely simultaneous, with countless relationships coexisting in time and space; we refer to them as trans-territorial.

At the same time, life is transmitted between different beings, moving, and transforming itself from one body to another through atoms and DNA IT unfolds in time and space, metamorphoses, and reincarnates, resulting from the interaction among coexisting and preceding beings. Therefore, life is historical and relational (Coccia, 2022). Furthermore, life is also social (cultural-economic-political-environmental) and occurs in historical phases, with countless successions and transformations, that we consider to be trans-temporal.

Life, then, occurs daily as a process in time and space with a duration and a territorialization. The latter relies on the community as an essential scale for democracy and the preservation of life, a process in which the simultaneous interaction of diverse interconnected and inseparable realities becomes increasingly evident. To preserve life, the community needs to take place necessarily in a solidary, plural, and sustainable manner, where we can recognize identities, voices, and feelings, as well as practice the democracy that safeguards life (Shiva, 2006).

In this sense of exteriority-alterity-temporal and territorial-, that is, of territorialities that outstrip academicist research, the research method is also considered at the level of education (teaching-learning). At the same time, it can be used as a method of action and cooperation with the subjects of each project. Thus, it can (im)materialize itself as a versatile and cross-cutting movement of participatory-action-research, as we will demonstrate below, built from a perspective that we consider decolonial and counter-hegemonic.

We have been experimenting with this concept over the years from both inside and outside the university, namely in classrooms, research, and university outreach; the latter formerly referred to as an approach oriented towards cooperation in the university-territory interface. This means that the subjects of each project are not objectified as mere providers of data and information, but rather understood as subjects just like researchers, with thoughts, knowledge, difficulties, needs, desires, etc.

Based on the research and action projects we have carried out since 1996 (Saquet, 2020), it is also essential to in(sub)vert the Euro-North-centric methods and paradigms considered as "modern" and "postmodern", which we often "simply" reproduce as models applicable to any territorial reality. This is an essential condition for thinking and building what we call the method of coexistences to act (in research-education-cooperation) centered around the university-territory interface, with the aim of constructing a fairer and more ecological society.

To understand the university-territory interface in its multidimensionality and to act upon it in a horizontal, participatory, respectful, and dialogical manner- as we have experienced despite the many challenges and difficulties we have faced over the years-it is essential to overcome Euro-North-centrism, namely academicism, urban-centrism, universalism, colonialism, and globalism inherent in hegemonic methods used in sciences like Geography.

Instead of dichotomizing subject and object, society and nature, university and territory, science and popular knowledge, it is crucial to reconstruct theories and redefine concepts and techniques while respecting the subjects, their choices, knowledges, trajectories, and cultural memories to jointly build knowledges that are increasingly useful for living a better and more fulfilling life, while teaching and learning, researching and cooperating. These processes involve the attainment of decision-making autonomy within and outside the university (Freire, 2011 [1974]).

Thus, the university, as one of the several existing educational levels, is understood as a territory linked to other territories through everyday and multidimensional territorialities and networks (Saquet, 2007, 2013, 2014, 2015 [2011], 2017b, 2019a, 2019b, 2020). It is a crucial territorial space-time for exposing dominations, coercions, degradations, bourgeois intellectualism, vulgar politics, corruption, and the centralization of power; as well as for co-producing versatile solutions for each territory, social group, and people. The university and scholarly research, when disconnected from the everyday life of our people (with regard to popular and more vulnerable social classes), even if critical, are not sufficient neither to overcome the conditions of poverty and misery faced by billions of people to address serious environmental impacts.

2. Decoloniality-liberation versus coloniality-domination

Overcoming colonization and coloniality is fundamental, considering its complex multidimensionality that has been reproduced for centuries in Latin America, both before and after the so-called political-administrative independences, as accurately characterized by Fals Borda (1979 [1968]) as "unfinished revolutions", precisely due to the perpetuation of dependency and subordination, the control and the hegemony of so-called global countries and actors. "The old value structure and the ritual sense of colonial society were not seriously affected" (Fals Borda, 1979 [1968], p. 40).

In the cruel process of European conquest, invasion, and colonization of Latin America, there was a dominating expansion that "murders the other" and reproduces a hegemonic culture, economy, politics, as well as the "modern" European philosophy. The latter, from its Hellenistic-Roman origins, aligns with the interests of the dominant slaveholding classes (Dussel, 1980).

Many indigenous peoples were initially co-opted and enslaved, but the overwhelming process of conquest was not limited to the first nations, as it expanded over time and space by submerging local classes in different countries and eras. They even incorporated many intellectuals who adopted theories, techniques, concepts, and practices of the colonizer by wearing masks, as eloquently explained by Fanon (2009 [1952]). Western "modern" science is oriented towards specialization and the fragmentation of reality, as well as its universalization and commodification (Toledo & Barrera-Bassols, 2008).

To assimilate the oppressor's culture and venture into it, the colonized had to provide guarantees. Among other things, they had to adopt the forms of thought of the colonial bourgeoisie (Fanon, 2005 [1961], p. 66).

However, this North-South domination is not the only one; there is also vertical domination between capital and labor; or erotic-social domination between men and women; or ideological-cultural domination (between parents and children; between the dominant state or culture and popular culture) (Dussel, 1997, p. 107).

Such "vertical" domination occurs, for example, with the Mapuche people-and many other indigenous groups-who are not recognized neither by the State nor within the society they live in, that is notably capitalist. Indigenous people are marginalized and negated within the capitalist mode of production and the historical and geographical reproduction of colonial power; it leads to the suppression of their knowledge and ways of life.

The "other" is situated in the "lower" part of the trans-temporal and trans-territorial relationship, and as a result, they can be crushed, buried, enslaved, controlled, punished, made invisible, and violently oppressed in different aspects of everyday life. This perpetuates what Fanon (2009 [1952]) recognized as the misery of the philosophy inherent in the "civilizing colonial world." Whose colonization and civilization? How and why so?

Colonization was carried out by pirates, miners, traders, and industrialists driven by greed, brutalization, violence, hatred, massacres, slavery, dehumanization, and the disdain for the "native" people. They imposed cultural domination and submission, thus reducing the "other" to mere objects (Césaire, 2020 [1955]). "I am talking about millions of men in whom fear, inferiority complexes, timidity, subservience, and despair have been cleverly instilled" (Césaire, 2020 [1955], p. 25).

Thus, we understand that the predatory coloniality is a multidimensional and multidirectional phenomenon, as illustrated by Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, Albert Memmi, and Enrique Dussel. It was carried out by "henchmen of capitalism", who may very well be intellectuals, referred to here as bourgeois. They reproduce themselves particularly in colonized countries, where they are often feared and admired, driven by a desire to be like the colonizer-from the metro-polis-and bask in the same privileges. The bourgeois intellectual imitates, threatens, punishes, co-opts, and mystifies, all while being co-opted and mystified themselves! Colonization and coloniality are economic, political, and cultural processes carried out by usurpers who employ various mechanisms of oppression, domination, contempt, and racism. It perpetuates poverty, disease, and hunger; thus characterizing the internal-external, dialectical, oppressive, and dehumanizing colonialism (Memmi, 2021 [1955-56]).

Historically, both inside and outside the university, it seems to be a "praxis of domination" that occurs under a philosophy of repression and control, as an imperial strategy (Dussel, 1980) serving conservative purposes and contributing to the expropriation of the other (Dussel, 1986). This expropriation is violent and cruel, driven by the diffusion of capitalist ideology, in which land is considered "passive" and belonging to "no one", while knowledge becomes monocultural, thus establishing a diversity of private property in colonized territories (Shiva, 2006). This process is directly linked to colonial and capitalist expansion, which is domineering and dispossessing, (im)materialized through economic, (geo) political, cultural, and environmental practices that extend across different educational levels, including universities.

Colonization, coloniality, and the praxis of domination can only be overcome through the "suppression of the colonial relationship", which requires the uprising and revolution of the colonized, effectively breaking the "colonial condition" (Memmi, 2021 [1955-56]). It is necessary and urgent to build decision-making autonomy and liberation, recognizing oneself as subjects and practicing self-management, identifying oneself with the people, and engaging in communication with it based on class struggle and place [struggle].

So, it is also crucial to revolutionize the social sciences, such as Geography, in theoretical, conceptual, methodological, and political spheres by contributing systematically and intensively to drastically part with the domination of positivist empiricism, deductive logic, as well as "modern" and "postmodern" theories (materialist, immaterialist, and hybrid), which are academicist, universalistic, globalizing, and urban-centric. All these theories historically contributed to the objectification of both subjects and nature, external to our bodies, and to commodify them within a worldview that seems to be bound by capitalism and globalization.

Thus, decolonization and liberation are urgent and vital for our people from popular and the most vulnerable classes, whether in rural and urban areas. Decolonization needs to occur through a movement of subversion and counter-hegemony. For us, it is understood as a process aimed at creating a "new human being" through the liberation struggle (Fanon, 2005 [1961]), enabling a concrete freedom to plant, harvest, and eat; to transform and take ownership of the results of one's labor, to sing and dance, to wander and teach, to learn and inhabit, to feel secure and have good health, to think and produce one's existence according to one's own needs and desires.

Counter-hegemony "[...] is fully realized when the subaltern condition of the popular classes is broken [...]" (Hidalgo Flor, 2015, p. 140). It is evidently a slow and challenging process, as opposed to the predatory, oppressive, and expropriating colonization and hegemony. It is also, contrary to the colonial face of "modernity" and "postmodernity". This also implies producing another philosophy "of existence", according to Márquez Fernández (2015), and, for us, a Geography and praxis of research-education-action/ cooperation. Counter-hegemony can occur within Indigenous', Afro-descendant's, peasant's, student's, teacher's, worker's, etc. social and territorial movements, whenever there is debate and self-recognition, class and place consciousness, shared synergies and solidarity, democratization and community life, environmental sustainability.

This can be achieved through movements of criticism and contestation of coloniality and "modernity", (im)materialized as processes of decolonization and counter-hegemony through a liberating praxis that breaks away from dominant paradigms (productive, commercial, financial, scientific, political, cultural, and environmental) and embraces "alternative" processes centered on well-being, social participation, and democracy. It involves revolutionizing power through an activist, co-participatory, deliberative, debated, and community-oriented praxis (Márquez Fernández, 2015).

Thus, we can understand that there is a "de-colonial" movement taking place in different territories and times. It emerges from the social, ethical, political, and epistemic responses constructed within Indigenous and Afro-descendant movements (Walsh, 2014 [2008]). These responses condition the appearance of alternative ways of thinking and acting (Mignolo, 2003 [2000]). In this movement, which we consider to be trans-temporal and trans-territorial, academic and political, cultural and environmental, there is a need for a profound struggle against coloniality and its material, epistemic, and cultural effects, e.g., the normalization of extermination, domination, subordination, land expropriation, death, torture, rape, colonization of thought, etc. (Maldonado-Torres, 2018).

Decolonization and decoloniality, therefore, should correspond to a process of critical research, contestation, and activism toward a radical change in hegemony and coloniality (Maldonado-Torres, 2008). For us, drawing from our previous learning derived from action-research, decolonization and decoloniality can only occur alongside an effective "praxis of liberation" that subverts the dominant status quo. It could be related to class, nation, gender, pedagogy, or political and cultural realms (Dussel, 1980, 1986), in a constant struggle against poverty, exploitation, and injustice (Dussel, 1997).

This requires reflection-action/cooperation engaged politically with the people, working for and with them, with particular emphasis on the university-territory interface. Research-education-cooperation needs to be formative, processual, dialogical, reflective, and participatory, embodying a praxis of communicative reciprocity and popular liberation (Freire, 2018 [1968]).

Liberation is only possible when we have the courage to be atheists of the empires of the center, thus facing the risk of suffering their power, their economic boycotts, their armies and their agents of corruption, murder and violence (Dussel, 1980, p. 15).

We need a reasoning that is not limited to the ability to process information and the use of techniques [...]. We have to [...] break with the stereotype of the intellectual limited to the management of the universal accumulation of knowledge (Zemelman, 2011 [2005], p. 278).

Thus, we understand that the praxis of liberation needs to be our object of study and action/cooperation working at the university-territory interface, with urban and/or rural communities, through a method of phases and, especially, of coexistence, concretely contributing to the production of a popular territorial science (PTS) (Saquet, 2022a).

As our life is historical and relational, in phases and simultaneities, it seems very appropriate and necessary to try to advance qualitatively in the construction of a method that recognizes cosmological and universal unity. "[...] Each one lives from the body of the other. [...] Each territory is a metamorphosis in progress [...]" (Coccia, 2022, p. 164). "Everything belongs to other lives, it has already lived several forms and times, everything is readapted, resystematized, reformed" (Coccia, 2022, p. 109).

Therefore, our experience clearly reveals that methodological coexistence is one of the fundamental conditions of Participatory-Action-Research [Investigación-Acción-Participativa - IAP by its original formulation in Spanish] and PTS to co-produce multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary knowledge. In this way, we have been able to collaborate historically and continue to cooperate directly to identify, understand, represent, explain, and enhance the singularities of each territory in favor of its inhabitants, particularly the most politically, culturally, and economically vulnerable classes.

As Juana Júlia Guzmán-one of the peasants who inspired other Colombian workers in the early 1970s during their political struggles for land and territory-has cogently stated: "Cowards do not make history" (Rappaport, 2020). They may make history in academia by coveting political positions, achieving citations with exciting texts, but they are certainly not making history toward the people, working and fighting with them.

We have been working through participatory-action-research, in the wider framework of qualitative research, at the territorial level of urban and rural communities because this is the scale that has been most coherent for cooperating directly with the people. We move inside and outside the university by theoretical-methodological and political phases and coexistences. Within the community, we have identified solidarity and sharing, benevolence and cooperation, synergy and respect, human beings very close (culturally, affectively, and politically) to each other. They reproduce relationships that are part of a "communitarian praxis", as argued by Dussel (1986). Communities contain subjective and cultural, affective and political recognitions between subjects and their daily spaces, with their identities and knowledge, food and heritage (Giuca, 2019).

Those communitarian aspects are also identified and qualified by Gonçalves (2022) by highlighting the affective subjective relationships between subjects who share the same cultural tradition and a "solidary territorial order", in the broad sense of the reciprocity practiced in certain territories and at certain times. Knowledge is passed on from generation to generation, with common gains and experiences.

In the communitarian feeling, aspects such as customs, linguistics or even behavior underpin social awareness about the existence of the community and its recognition. The bonds of social solidarity are referenced in reciprocal actions in which no one is disadvantaged and the whole community is fulfilled by learning (Gonçalves, 2022, p. 66).

In urban and rural communities, we have researched and acted upon over the years (Rio Grande do Sul and Paraná, Brazil) by teaching and learning the method of coexistences in a practical way. In those communities, territorial mobilization and self-organization are very present, usually based on a community identity and political-cultural differences. Amid the contradictions and challenges of participatory-action-research, we create networks of cooperation and solidarity at different scalar levels. There, the State is often totally or partially absent, it does not do its constitutionally required duties in terms of building a fairer and more sustainable society for all.

As expected, we have historically experienced many difficulties such as the State's and political parties' contempt, irregular urban occupations, environmental degradation, lack of basic sanitation, and others related to urban and rural infrastructure. Self-organization and mobilization, as well as struggle and continuous confrontation, are contingent on these processes, although they are often ephemeral, depending on the territorial conditions, needs, desires and objectives of each group and social class. Self-management can arise out of the contradictory and complex communitarian lives, diversity and synergy, carried out by the inhabitants of each territory and community, including a sustainable, multidimensional, and trans-scalar praxis, as already evidenced in Saquet (2015 [2011], 2017a, 2017b, 2018a, 2019a, 2019b, 2020, 2022a).

3. The method of coexistences in participatory-action-research

We do not believe in the neutrality of science, teaching-learning, research and action. We think that there are sciences (not always theorized) in practices and practices in sciences. Science is a political movement of confrontation (PMC), of mobilization and (in) formation practices (MIP), of solidarity and cooperative actions (SCA), and of participatory-action-research (PAR). It results, then, in what we call popular territorial science (PTS) (Saquet, 2020, 2022a).

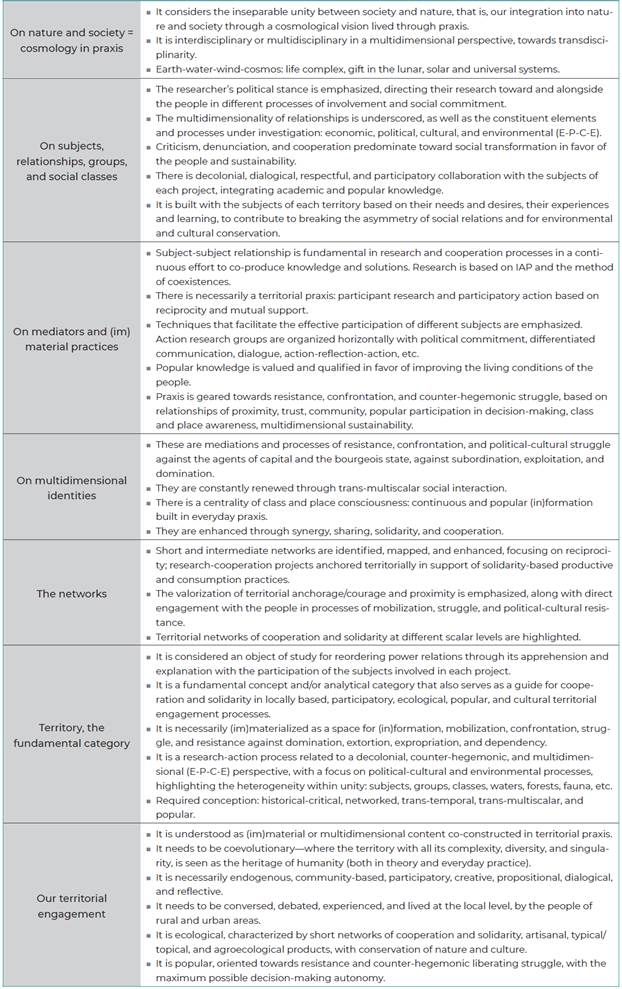

To this end, one of the fundamental premises is to know and practice Freire's "pedagogy of the oppressed, autonomy and hope" (2011 [1974], 2011 [1996], 2016 [1992]), as well as the PAR and Fals Borda's "popular science" (2011 [1967], 1978, 2015 [1979], 2006 [1980], 1981). We theorize and act inside and outside the university, teaching and learning, researching in phases and with coexisting activities, in transtemporal, transmultiscalar, and trans-territorial processes (Table 1), always envisioning direct collaboration to solve everyday problems.

Participatory-Action-Research is a method, as well as a participative action; therefore, it requires recognition and valorization of the research subjects and their knowledge, cosmologies, techniques, and ecosystems. It requires humility and respect from the researcher, dialogue and reflection, as well as boldness and methodological versatility to simultaneously research and cooperate. Following the reasoning of Rappaport (2020), JuanaJulia Guzmán (activist) and Orlando Fals Borda (educator) represented two groups and initiatives that resulted, in the early 1970s, in what Fals Borda called "action research" and a symbiosis between "people's knowledge" and "scientific knowledge".

It is relevant to note that amidst peasant and workers' struggles, in different countries like Brazil and Colombia, "alternative approaches" to research are produced through partnerships between radical Latin American social scientists (such as Orlando Fals Borda and Paulo Freire) and leaders of rural social movements. They are among academic science and popular knowledge, research, and militant political action.

In the process, a dynamic synergy would evolve between the act of investigation and that of using its results to transform existing social relationships. Rigorous empirical research would contribute to the development of new political strategies, while the political agency of the coresearchers would lead them to establish novel investigative agendas (Rappaport, 2020, p. 8).

Such movement of university-territory integration through participatory action research seems to be revitalizing in Latin America. For instance, we highlight three doctoral theses. IN Argentina, Canevari (2021) creatively combines common techniques of academic science with others that are not widely used, as they are part of PAR, within the scope of popular education-that is, non-hegemonic. His research practice is shared in transformative processes within a peripheral urban community in La PLata, where theory guides the action-research, and at the same time, it is revised based on empirical research and cooperation carried out during their doctoral studies.

In Brazil, Silva (2022) also adopts Participatory-Action-Research as a theoretical-methodological framework, with Paulo Freire and Orlando Fals Borda as fundamental references, in an effort to conduct research in successive and coexisting phases, particularly in collaboration with quilombola subjects (Afro-descendants). The research itself is a political action anchored in the rural community and its culture, working at the interface between popular knowledge and science. It helps identifying urgent needs, and valuing the individuals while solving some of their common problems.

Lastly, in Mexico, García Ángel (2022) also conducts her doctoral research based on the approach of participatory-action-research, employing qualitative techniques and, notably, engaging in dialogue with the research subjects (peasants) to understand their experiences, struggles, and resistances. Aspects of the peasant's "feeling-thinking-acting" are highlighted, emphasizing the importance of autonomy in decision-making and exploring the differences and similarities between movements in Mexico and Colombia. Therefore, the concept of territory is fundamental, understood as a historical-social construction shaped through praxis and everyday experiences, with emotions and reason, and encompassing disputes and solidarities.

In general, it involves the participation of the researcher and other subjects in each project, a process that needs to go beyond inviting peasants or other workers to collect data or presenting our analyses to them. It needs to be a movement of reciprocal learning, where popular and scientific knowledge are integrated theoretically, methodologically, and politically towards a common goal. Hence the centrality of the method of coexistences. By researching only in phases, it will be much more challenging to teach and learn simultaneously, co-produce knowledge, and generate popular and sustainable solutions.

During PAR, to understand territorial singularities and treasure them toward building a life with identity and autonomy, it is necessary to invest time in debates, popular participation, coexistence, and shared management. In this way, qualitative research will capture more details and nuances that can guide the creative invention of the future based on "us, community members" and local networks of cooperation and solidarity. It involves recognizing and valuing the territorial heritage by the local society (Saquet, 2017b).

We should not eliminate the "human experience", our feelings, and our suffering from research and analysis. The bourgeois intellectual does not engage with the common people, with the country's population; they indulge in frivolous pleasures typical of bourgeois life, enjoying many privileges exclusive to their peers. "To be on the left or the right is not only a way of thinking but also (perhaps above all) a way of feeling and living" (Memmi, 2021 [1955-56], p. 63).

This way of feeling and living, for example, is identified among the Mapuche people (Chile) and their territory because this relationship is inseparable: the foundation of their daily life and their biological and social reproduction (Mansilla Quiñones, 2018). In this way, we can research and cooperate, teach and learn, by building "spaces of learning for the incorporation of subjects" (Zemelman, 2006 [2003]), constructing knowledge through debate and creativity, integrating the university and the territory. Dialogical and horizontal mediation is vital to produce increasingly useful knowledge to support popular projects, which have their potential in the conscious social subject, rescuing and valuing their desires, needs, and decisions (Zemelman, 2011 [1989]).

In general, we can carry out: i) studies on the territorial praxis of domination and/or liberation (from outside and about it) in a critical approach of denunciation focused on the subject-object relationship; ii) studies focused on the praxis of resistance and decolonial confrontation, thus providing support to the popular struggle; iii) studies participating in the territorial praxis of liberation, carried out with the subjects of each participatory-action-research project, necessarily focused on the subject-subject relationship and from a decolonial and counter-hegemonic perspective.

We position ourselves in this last conception and option, even though we know that studies of territorial topics (at different scales) in Geography usually occur in a deductive manner; that is, from the global to the local, emphasizing international subjects and processes conditioning individuals and other phenomena in neighborhoods, cities, rural communities, and municipalities. It involves a thorough and lengthy literature review followed by the collection of secondary data, the construction of (mainly digital) maps, and the collection and analysis of primary data. A significant portion of the time spent during a master's or doctoral program is dedicated to taking courses and conducting literature reviews, resulting in long chapters that are often disconnected from each other.

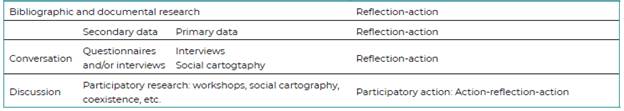

In our participatory and popular territorial option, we do not disregard the aforementioned phases, but we shorten their duration to carry out coexisting activities, such as collecting primary and secondary data, along with social and digital cartography. Whenever possible, we cooperate directly with the subjects of each project, and we aim to avoid long and tiresome chapters that are too theoretical and disconnected from the study's topic and problems. We try to describe and analyze the "object of study" right at the introduction of the master's thesis or doctoral dissertation to gain depth in the analysis and participatory-action-research (Table 2).

TABLE 2 FORMS OF PRODUCING SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE (EXEMPLIFIED BY THE TOPIC OF AGROECOLOGY)

SOURCE: Adapted from Saquet (2022b).

The research process and the production of knowledge focus on the relationship between space, time, and territory, hence, on their historical successions and coexistences, which we emphasize in the PTS. THrough various completed action-research projects, we have found the need to balance both trans-temporality (historical) and transterritoriality (simultaneous) by working simultaneously with literature and document research, by collecting secondary and primary data (including tabulation, representation, and analysis), as well as conducting workshops and other qualitative activities such as participant observation and social mapping (Table 3). All these techniques are fundamental, complement each other, and contribute effectively to a proper and in-depth understanding of the "object of study" and reordering of power relations, all while caring for nature and the community. These principles form the basis of a decolonial and counter-hegemonic participatory-action-research approach.

Over the years, there has been a strong emphasis in our projects on participatory social cartography because it is essential to identify territorial references and their meanings, including mental maps (Dansero et al., 2019; Amato & Matarazzo, 2023). Through social cartography, collective data and representations are recorded; it also serves as a tool for defending the rights of indigenous peoples based on their identities and territorialities (Pelegrina, 2020; Bonfá Neto & Suzuki, 2023). The cartography is made through participant observation, interviews, and workshops by engaging with community members and recording their interpretations of their everyday lives from an "anticolonial" perspective of political and cultural resistance (Bonfá Neto & Suzuki, 2023). This approach is one way to democratize access to data, maps, and other information that are part of each scientific research project. Furthermore, participatory cartography is a powerful tool for recognition, identification, mobilization, and struggle.

Participatory cartography, integrated with territorial planning, mobilizes and connects actors to territories, while also involving these actors in the production of knowledge about the territory, with the potential to contribute to sustainable territorial development (Bonfá Neto and Suzuki, 2023, p. 7).

Some fundamental characteristics of researching and cooperating in phases and coexistences are methodological and conceptual versatility and the objectives and goals of each participatory-action-research project. These in face of a fleeting and uncertain socio-natural-cosmological reality, ephemeral and prolonged, unknown and known, (a) theoretical, (meta) physical, objective and subjective.

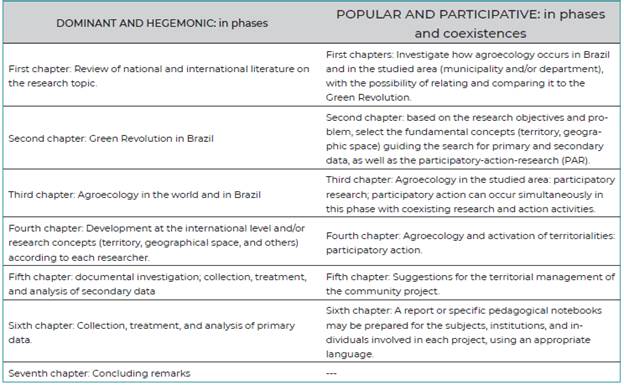

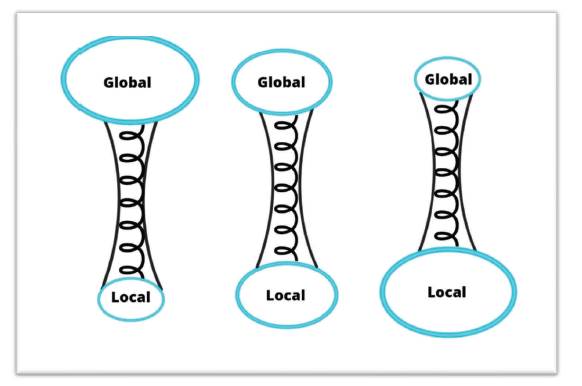

Versatility is essential in the method of coexistences because it allows us to balance, in terms of data and analysis, the scalar levels of the global and the local- should this be the researcher's choice-thus focusing more or less on trans-multiscale and transterritorial relationships and networks, as illustrated in Figure 1. The choice is technical, methodological, scientific, and obviously, political. It highlights the geographic phenomena and processes that the researcher (from different genders of identity) deems essential to carry out their participatory-action-research to support the coproduction of knowledge and the popular classes, who are more economically, politically, culturally, and environmentally vulnerable.

SOURCE: created by Marcos Saquet, 2023; illustrated by Felipe Barradas Correia Castro Bastos.

FIGURE 1 Levels of research and reflection on the relations of totality between the local and the global

In any case, we think it is essential to always take into account the natural-cosmological-social coevolution that conditions historical and relational/coexistent life: we reproduce ourselves in a continuous struggle between life and death, in phases and simultaneities. Thus, in each participatory-action-research project, we can afford more or less emphasis on the local and the community (Figure 2), considering this scalar level as the most appropriate for co-constructing the solutions that our people so desperately need. This is based on a theoretical-conceptual and empirical depth, social immersion, and territorial anchorage, sharing problems and solutions that are often useful to us as students, professors, and researchers. "The changes we are able to achieve may seem of little importance, but the impact they produce will be crucial for the fate of the planet and humanity" (Shiva, 2006, p. 11).

SOURCE: created by Marcos Saquet, 2023; illustrated by Felipe Barradas Correia Castro Bastos.

FIGURE 2 Levels of research and reflection on the local and the global

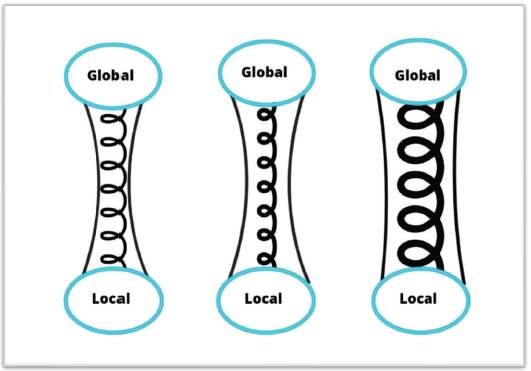

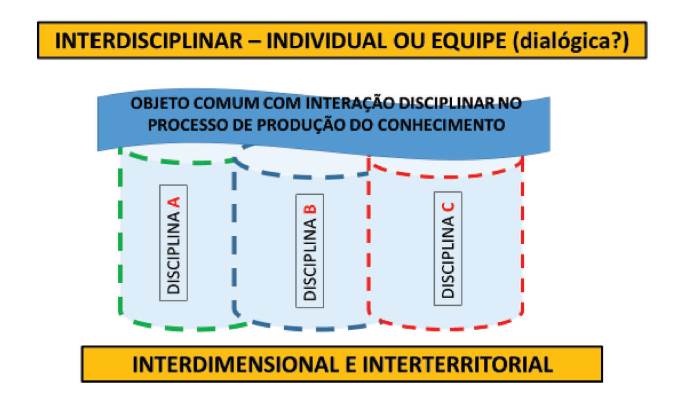

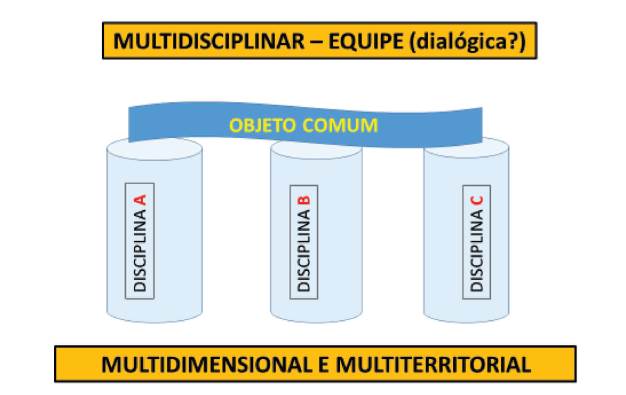

Participatory and participative research, happening simultaneously, are usually interdisciplinary (Figure 3) or multidisciplinary (Figure 4). They can occur during the master's and/or doctoral programs, either individually-as we conduct our master's and doctoral research practically on our own, although accompanied by a thesis advisor-or as a team. In the latter case, bringing together professionals from different fields of knowledge facilitates interdisciplinarity or multidisciplinarity, considering the different dimensions of life (social and natural) and scales of the territory (transterritoriality).

SOURCE: Elaborated by Marcos Saquet, 2023.

FIGURE 3 Interdisciplinarity in territorial and popular scientific research

SOURCE: Elaborated by Marcos Saquet, 2023.

FIGURE 4 Multidisciplinarity in territorial and popular scientific research

In an interdisciplinary perspective, whether in an individual or collective project, there is a need to recognize, research, and analyze elements and processes considering the unity of society-nature, time-space-territory, urban-rural, etc., according to each participatory-action-research project's topic and objectives. The integration of knowledge should occur in the movement of action research, in all its phases, from the project elaboration to the implementation of cooperation with the subjects (through coexistent activities).

In a multidisciplinary perspective, there is no fundamental requirement to integrate knowledges, techniques, theories, and concepts throughout the research and action process. The multidisciplinary team members can conduct research and activities separately while sharing the same objectives and bringing together their analyses and collaborations while writing the research report or master's or doctoral thesis. The student should engage in dialogue with professionals from other fields of knowledge during their program. It is important to note that this is one way to understand multidisciplinarity in territorial and popular scientific research, as we have argued, but it is not the only way. There are other approaches that we have not discussed in this text.

Our experience with participatory-action-research reveals a predominance of interdisciplinary research, conducted as described earlier, and this allowed us to co-produce a popular territorial science in a praxis movement between the university and territory, simultaneously constructing knowledge, thoughts, and actions (Saquet, 2015 [2011], 2018a, 2020, 2022a, 2022b). The co-production of knowledge has the potential to reconfigure power relations and contribute to breaking the dichotomy between specialized and local knowledge (Toro-Mayorga and Dupuits, 2021).

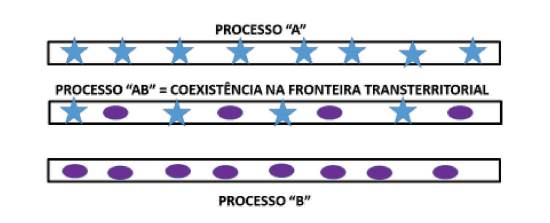

The process in which the present, past, and future signify historical movement and simultaneity-in everyday life and in research conducted in phases and coexistences-characterizes a constantly transtemporal, processual, and coexistent/relational/reticular movement: in the materiality of everyday life, this movement is unique (Figure 5 -process "AB").

SOURCE: Elaborated by Marcos Saquet, 2023.

FIGURE 5 The coexistence of life and territorial popular science

Processual transtemporality corresponds to phases, successions, periods, and historical moments. Coexistent transtemporality refers to concurrent relations and events, whether similar or different, occurring at different rhythms, trans-multiscalar and transterritorial levels, in the same or between different places, in the same or across different times. We experience multiple temporalities simultaneously (past, present, and future) as well as multiple territorialities (local and at different scalar levels) happening simultaneously (Saquet, 2007, 2015 [2011], 2017b, 2018b, 2019a, 2019b, 2020).

Thus, the PAR based on the method of coexistences and a perspective of popular, territorial, and decolonial praxis corresponds to a "revolutionary pedagogy of struggle and liberation" (Fanon, 1974), in other words, a historical-critical and political pedagogy (Fals Borda, 2015 [1979]). "The masses, as active subjects, are the ones who justify the presence of the researcher and their contribution to concrete tasks, in the active stage and in reflection" (Fals Borda, 2015 [1979], p. 263).

In this way, the process of research and knowledge production is directly linked to the action of the subjects involved in them, living in society, in time and space, co-producing unique territories of life. The produced knowledge must enrich our capacity for action based on everyday life, experiences, subjects, and their needs, in short, the "horizon of existing possibilities" (Zemelman, 2011 [1998]) in each time and territory.

4. Concluding remarks

We believe that the participatory-action-research built from the method of coexistences, without disregarding the specific historical phases of each scientific inquiry, forms a movement toward a popular territorial science and the cooperative solidarity in favor of life itself. This is how we conceive and affect the university-territory interface. It is a fundamental way to achieve decision-making autonomy, to co-produce knowledge by integrating science and popular wisdom through social immersion and territorial anchorage, thus contributing much more than we currently do to solve problems faced by the popular classes. The praxis of action research, conducted in this manner, becomes essential for the construction of a more just and ecological society, materialized as a territorial praxis of liberation (also territorial), as we have already demonstrated.

This is also a way to observe and recognize the other personified in their own territory, with their own name, senses, emotions, desires, and unique embodiments (Mansilla Quiñones, 2018). In the minds of indigenous peoples, peasants, and quilombolas (Afro-descendants), there existed and still exists a detailed knowledge of nature (Earth-Moon-Sun-Cosmos) and the territorial relationships they had and have with the land, water, forests, and other animals. This knowledge can only be understood, represented, valued, and enhanced through an appropriate method that integrates knowledge and sciences, society-nature, rural-urban, intellectuals-people, body-Earth-cosmos.

This means that within the university, we need to assume even greater social, economic, cultural, environmental, and, obviously, scientific responsibilities in favor of a popular territorial science that is increasingly useful for our people, directly contributing to the qualification and strengthening of community self-organization. At the same time, it is crucial to build local public policies that must necessarily operate at different scales, such as municipal, intermunicipal, regional, national, etc., according to the needs of each society, while considering the conservation of nature and culture.

Therefore, based on what we have learned through participatory-action-research conducted with the method of coexistences, we recognize that popular self-organization, as a part of the organized civil society, and the State are essential. All this by combining forces and sharing common goals to rediscover and revalue communities, their knowledges and techniques, their ecosystems and heritage, their identities and synergies, thus democratically reinventing their own future with maximum decision-making autonomy.

Self-organization and public policies can occur sequentially (constructed in historical phases) or simultaneously in time and space, as we have argued throughout this text, but they need to be directly linked to the daily life and the problems faced by the popular classes. In doing so, we can enhance and strengthen the university itself as a territory for research, education, reflection, and cooperation and contribute to overcome academicism, globalism, urban-centrism, and Euro-North-centrism inherent in abstract theories, methods, and concepts. These are often inadequate for understanding, representing, explaining, and co-transforming communities and territories toward a more just and ecological society.

It is therefore necessary to revolutionize the sciences and universities. In doing so, we can inspire and establish decolonial and counter-hegemonic theories developed with appropriate and coherent methods with the singularities of each time and territory. This can be achieved through the interface between the university and the territory, making a concrete contribution to breaking free from the coloniality of power and the classification of races (racism), as well as sexism and patriarchy. By doing so, we can qualitatively overcome the extreme social and territorial inequalities that exist in Latin America.