Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a combination of symptoms that manifests in an individual following direct or indirect exposure to an event that affects the person's life, health, or integrity. The individual starts avoiding both the associated memories and the related external stimuli. However, intrusive symptoms in the form of flashbacks, nightmares, and undesirable and involuntary re-experiencing of the event often occur. This causes psychological and physiological discomfort that increases the state of alertness directed to evade these re-experiencing symptoms, which manifest in hypervigilance, exaggerated startle reaction, irritability, lack of concentration, sleeplessness, and reckless or self-destructive behaviors. These are accompanied by: alterations in cognitions, which include negative irrational beliefs about oneself, others, the world; persistent alterations in mood, such as negative emotional states; along with dissociative symptoms, such as social detachment and/or estrangement. These symptoms persist for at least a month and cause significant impairment in the person's functioning. (Asociación Psiquiátrica Americana, 2014) PTSD damages the quality and the prospects of life, inter-personal relationships, and inclusion and growth into society (National Institute of Mental Health , 2008).

Around 1.8 % of Colombians have suffered from PTSD once in their life span (Ministerio de la Protección Social, 2005) [Ministry of Social Protection]. However, the prevalence of the PTSD increases significantly in a population exposed to serious events such as those related to any kind of abuse (Mingote, Machón, Isla, Perris, & Nieto, 2001). In Colombia, 49,807 children or adolescents were admitted into shelters in 2013 because of abuse-related trauma (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar, 2014) [Colombian Institute of Family Welfare]. In this population, PTSD levels can reach as high as 50 % (Mingote, et al., 2001).

Typically, PTSD is managed with medication, which causes secondary symptoms, and by conventional psychotherapy, which generally is better suited for adults. Therefore, it is important to seek for new, non-secondary effect approaches, in order to manage PTSD, in a way that is appropriate for children, and easily applied in group sessions meant for obtaining an efficient outcome. In this aspect, we propose EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques), which consist on the stimulation of some specific points in the acupuncture channel system, while recalling the memories or symptoms the individual wishes to overcome (EFT Universe, 2010). The presence of a system of electromagnetic channels has been shown in millivolts (Becker, 1985). The stimulation of this system causes the central release of endorphins, which decrease the sensation of pain (Giralt, 2009). Currently, the effectiveness of acupuncture has been demonstrated in diverse disorders, included PTSD (Kim YD, Heo I, Shin BC, Crawford C, Kang HW, Lim JH, 2013). Unlike acupuncture, EFT uses tactile stimulation instead of needles: various controlled and randomized studies have shown the effectiveness of acupressure in the decrease of anxiety (Meeks, Wetherell, Irwin, Redwine, & Jeste, 2007; Valiee, Bassampour, Nasrabadi, Pouresmaeil, & Mehran, 2012; Wang, Escalera, Lin, Maranets, & Kain, 2008).

Additionally, EFT includes a thoracic massage below the middle section of the clavicle, known as "the sensitive point." It is believed that this massage works on the intercostal nerves and, thereby, decreases the sympathetic over-stimulation of the intermediolateral horn (Caso, 2004). Although the underlying mechanism of thoracic massage effects is still not clear, some evidence has proven its influence on the autonomous system (Fossum, Kuchera, Devine, & Wilson, 2011).

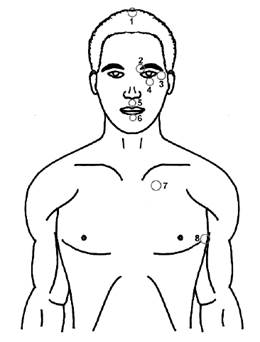

The "abbreviated basic recipe" of EFT consists on the following steps: (1) Problem: identify the treatment's objective. (2) Assessment: identify the related symptoms and their individual perceived level (from o-nothing to 10-the highest). (3) Preparation: massage the "sore spot" while a phrase of self-acceptance is being declared regardless of the incident or symptom. (4) Tapping: give taps with the fingers over an initial or ending point, of each one of the principal energy channels of acupuncture (Figure 1). (5) Re-assessment: once the tapping round has been concluded, the level needs to be reassessed. If it has diminished, steps 3 to 5 should be repeated until reaching either a level 1 or a level o; if it remains the same, a dialog should be conducted with the individual in order to identify emerging thoughts, images, sensations, or feelings that are blocking the healing. These should be treated as if they were a separate problem, while going back to the original problem at a later time (Craig G., 2016).

The downside to EFT consists on the fact that its protocols are repetitive and monotonous, which are unpleasant for children. However, recreational activities can make it more appealing. We propose art-therapy, which "utilizes the artistic creation as a tool to facilitate the expression and resolution of emotions as well as emotional or psychological conflicts" (Asociación Profesional Española de Arteterapeutas, 2012). [Spanish Professional Association of Art-therapists]. This means that, in art-therapy, the importance is given not to the esthetic outcome but to its relation with regard to the psychological processes (Covarrubias, 2006). In art-therapy, the individuals express themselves from a distance, therefore, their observation is being made, not from the first person but rather from the third person. Moreover, the individuals start using non-verbal languages, such as plastic, sonic, or body language to represent their conflicts, fears, and aspirations, which brings about a greater awareness of these emotions (Klein, 2006). Among art-therapy methodologies applied in post-traumatic children, "plastic expression" has been widely utilized. It consists of the manipulation of materials, such as paints and modeling clay, in order to facilitate the expression and processing of the traumatic content (Valdivia, 2002). When this plastic expression is introduced in a recreational form, produces relaxing and pleasant emotions that offset the stress and negative emotions associated with the traumatic memories. This balances out the inclination to evade them, while motivating the participation of children in the mentioned activities and facilitating the expression and resolution of those memories (Trejos Parra, Cardona Giraldo, & Cano Echeverri, 2005).

Consequently, the objective of this study was to determine the effectiveness of EFT with a recreational plastic expression (RPE) program in post-traumatic stress of school age children boarded for abuse-related trauma.

Methods

Design

The design was made in the form of an experimental investigation, with an experimental group and a control group chosen randomly and with the inclusion of pre- and post-assessment values. It was presented to the Bioethics Committee of the University, showing that the risk involved was minimal (Ministerio de Salud, 1993) [Ministry of Health], since it only consisted on the discomfort experienced when recalling the traumatic events, which was part of the therapy protocols already established. Given that the potential benefit was the reduction or disappearance of PTSD symptoms, with the improvement in both the quality and the prospects of life, the protocol was granted the committee's approval.

Participants

The studied population consisted of 47 children boarded for abuse in four different shelters, listed in the "Colombian Institute of Family Welfare" (ICBF for its acronym in Spanish), which is a government entity dedicated to the comprehensive protection of children and adolescents, aiming to guarantee the exercise of their rights and freedoms. One of its strategies is to place children and adolescents in shelters for the restitution of their rights, which were violated due to either mistreatment or abandonment.

Children in each shelter were divided into an experimental group and a control group. The inclusion criteria were: (1) comply with the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD; (2) voluntary acceptance in the research participation; and (3) being between the ages of 7 and 14 years old (with younger individuals the DSM-5 criteria changes, and with older individuals, a more complex program would have to be implemented for middle as well as older adolescents). The exclusion criteria were: (1) the presence of evident cognitive or communication disorders; (2) taking part in other PTSD therapeutic processes; (3) suffering from a new emotional trauma during the course of the research; and (4) being absent from 20 % of the interventions. However, there was a high number of withdrawals caused by the mobility of this population, resulting in an experimental group of 27 children and a control group of 20 children. Of the 47 participants, 52 % were females and overall had lower school grade scores than expected for their age, given the established violence in either their social or family circumstances.

Experiment measuring Tool

The tool consisted of a gradual scale measuring the intensity and frequency of the symptoms, which was constructed with questions obtained from each of the PTSD symptomatic criteria specified by the DSM-5. The scale was adapted for the student population, not only in accordance with their literacy, but also by adding emoticons and explanatory drawings. Furthermore, the scale was validated through the judgment of six experts: three psychologists, one psychiatrist, one speech therapist, and one recreation professional; and by means of a pilot test on 39 children belonging to two institutions, resulting in an alpha coefficient Cronbach of o.934 (SPSS 17). The scale was completed by means of a personal interview conducted by the researchers to ensure the understanding of the questions and the validity of the information.

First, child abuse was explained, then the test was completed. It included the following questions. The first questions were answered with options: Yes/No. (A1) Have you ever experienced something like that? (A2) Have you ever seen that happen to someone close to you? If yes, then to whom and explain. (A3) Have you ever heard of that happening to someone close to you? If yes, then to whom and explain. (F) Did this occur more than 1 month ago?

The second questions were answered with frequency options: 2 - everyday, 1 -some days, o-never; and severity: 2- a lot, 1- more or less o-nothing. (B1) Have you had painful memories or repetitive play of punishment, mistreatment or abuse? (B3) Have you felt or acted as if it was happening again? (B4) Have you felt wrong emotionally by remembering it: shock, sadness, anger, etc.? (B5) Have you physically felt bad to remember it? With: sweating, tremors, palpitations, etc.? (C1) Have you tried to avoid remembering what happened? (C2) Have you avoided things or situations that remind you of it? (D1) Have you been able to remember what happened, in its entirety? (D2) Do you think negatively of yourself, of others or the world? For example: you are bad, you cannot trust anyone, or the world is dangerous? (D3) Do you feel guilty or blame others for what happened? (D4) Do you keep negative emotions, such as fear, sadness, anger, guilt? (D5) Are you still participating in activities that you enjoyed before? (D6) Do you feel distant or away from others? (D7) Do you continue feeling positive emotions, such as happiness, satisfaction, love? (E1) Do you get angry easily and attack others: yelling, insult others, strike others, are you crying, etc.? (E2) Do you participate in dangerous activities which endanger your health or your life? E3) Do you feel in danger? (E4) Do you get scared easily? E5) Do you have difficulty concentrating? E6) Do you have difficulty sleeping, or do you wake up during the night?

The experimental procedure

The experimental procedure consisted of three phases: (1) pre-assessment, (2) EFT with recreational plastic expression, and (3) post-assessment. During the pre-assessment phase, mistreatment, post-traumatic stress, plastic recreational expression, and EFT were presented and explained to the participants by means of videos and dramatization. Subsequently, the scale was implemented through a personal interview during which the drawings related to the different types of mistreatment were first presented and explained. Then, each question was explained in order to validate the child's understanding of the given question. Afterwards, a response to each question was requested from the child, with the support of an answer sheet showing numbers and emoticons that indicated the level of frequency and intensity related to the corresponding symptom. In addition to the scale, the levels of negative emotions were measured by means of the "Subjective Units of Distress" (from o-nothing to 10-the highest) before, during, and after each session in order to keep an accurate account related to the decrease of the symptoms. Additionally, observations were conducted during the interventions, and interviews were also conducted with the children and caretakers at the end of the intervention.

The RPE program consisted of six sessions that lasted for two hours each. Every session comprised a short psychomotor activation phase, a central phase of the aforementioned program, and a final phase of awareness into the present moment while generating positive emotions. A different material was used in each session: drawings, paint, collage, plasticine modeling, puppets, and masks. The program was organized in a progressive manner, in such a way that the recall of the memory was first obtained indirectly, then in a direct manner, while in the last session a new project of life without PTSD was developed. Three rounds of abbreviated basic EFT procedure were implemented each 10 minutes throughout the sessions. The EFT phrases were repeated using a song to make them more entertaining. The EFT Tapping Basic Recipe (with 8-points) was utilized with phrases such as "Even though this happened, I love myself the way I am" and "Even though this happened, I know how wonderful I am."

The post-assessment phase was performed one week after the last session took place. The data analysis was performed using MS Excel and SPSS 17 statistics software for Windows. The test between the experimental and control groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney test, and the pre vs. post-test with the Wilcoxon test. A 0.05 alpha was defined.

Results

One-tailed tests were used, given that, in accordance with the theoretical re-vision, the EFT by means of a RPE program could either diminish or leave the symptoms intact, but never increase them, like it indeed occurred. A one-tailed alpha test with a 0.05 level of significance was utilized.

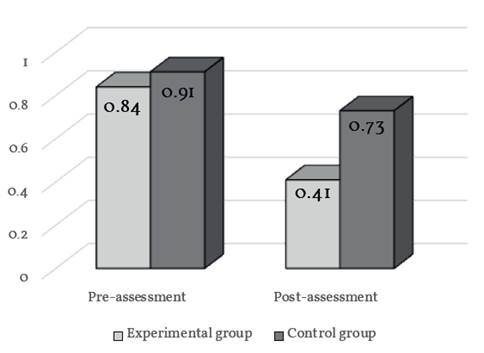

Figure 2 Changes in the symptom level of PTSD in school age children boarded for abuse. Colombia, 2015

No significant differences were observed between the pre-assessments of the experimental and control groups (p=0.257; Mann-Whitney). However, differences were observed between the post-assessment of experimental and control groups (p=0.002; Mann-Whitney). There were significant differences between the pre-assessment and the post-assessment in both groups (experimental group: p=0.000, control group: p=0.013; Wilcoxon). However, the group that participated in the RPE workshops and EFT procedure improved significantly more (0.43 points) compared with the control group (0.17 points), hence resulting in the significant difference between groups in the post-assessment. In accordance with this, 11 children of the experimental group (46 %) stopped experiencing PTSD symptoms in comparison with five children in the control group (28 %).

Although significant differences were observed between the experimental and control participants, not only globally but also per dimension, the control group also displayed a decrease in PTSD levels without even participating in the program. This improvement could have been due to the following factors: (i) the children had been placed in an environment where their rights were protected, away from the aggressive environment where they had lived the traumatic events; which may have spared them from new exposures to the traumatic experiences. Indeed, in 30 % of the individuals with PTSD, the symptoms disappear in the absence of any treatment (Sadock & Sadock, 2008). (2) An unexpected event was noticed during the post-assessment: the participants of the recreational program had taught the song with the EFT points to only some of their peers in the control group.

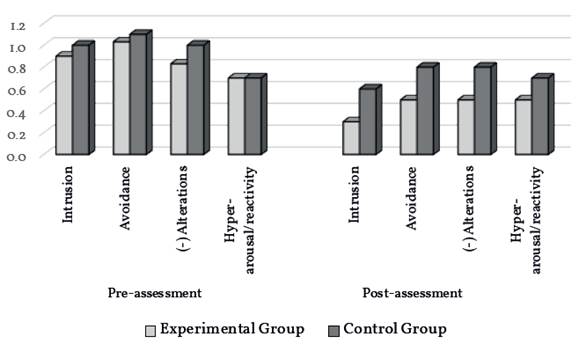

Figure 3 Changes in the symptom level of each PTSD criteria in school age children boarded for abuse. Colombia, 2015

The level of all DSM-5 symptomatic criteria decreased in both groups, in descending order: intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations, and hyper-arousal/ reactivity. In the pre-assessment, no significant differences were observed in any criteria between the experimental and control groups. In contrast, there were significant differences in the post-assessment, with the exception of some of the intrusion symptoms (p=0.058; Mann-Whitney). This suggests that intrusion symptoms are the most persistent among PTSD symptoms, maybe because the mind still continues trying to overcome the memories (Kolk, 2000).

During and after the interventions, additional observations were performed and were transferred into field diaries and semi-structured interviews. The information gathered in this qualitative evaluation corroborated quantitative findings and is discussed throughout the following section.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine the effectiveness of emotional freedom techniques with an RPE program in post-traumatic stress of school age children boarded for abuse-related trauma.

In light of our review of neuroimaging findings, PTSD can be considered to be generated by the dissociation between the right hemisphere, which encodes the event -implicit memory-, and the left hemisphere, which does not encode it -explicit memory-. Since in accordance with previous neuroimaging findings, when the experience is too intense for the person to bear, the right amygdala, and other associated structures, present hyperarousal, which inhibits other cerebral structures to contextualize and integrate the memory. Consequently, a hypofunction of the Broca area in the left hemisphere is observed. In this way, the event remains out of œntext and disintegrated; therefore, it becomes permanent and generates event-related dysphoric symptoms of hyperarousal, which are perceived as unwanted and intrusive. Subsequently, the avoidance symptoms emerge, making it more difficult to process the traumatic event (Kolk, 2000).

Consequently, management of PTSD requires looking for the processing of traumatic memories by facilitating their exposure, which diminishes the expected avoidance, thus bringing into the open the expression of traumatic events; so, the explicit memory can then code, integrate, and contextualize them. However, this expression should be carried out using strategies that allow the conscience to distance itself from the events, in order to avoid becoming overwhelmed by the associated sensations and emotions. Such strategies should facilitate the non-verbal expression, since the verbal language is obstructed in regard to the traumatic event. In contrast, interventions based only on verbal language have not demonstrated efficacy in reducing anxiety, probably because the amygdala is capable of controlling the superior cortical centers (Kolk, 2000). At this point, the RPE plays a key role since it is a non-verbal expression that allows a person to distance himself/herself from the traumatic memories.

Given the children's age, their verbal skills are still developing, which makes it harder for them to express their emotions in a verbal manner. Therefore, the utilization of non-verbal techniques is necessary in the psychotherapeutic processes of PTSD in children. These include drawings, paintings, modeling clay, or puppet activities (Valdivia, 2002). Moreover, RPE allows children to exteriorize their emotions and perceptions, increase their self-knowledge, reveal their inner world, and reorganize information from a new perspective, thus contributing to the integration of their personality and the improvement of the quality of their life (Covarrubias, 2006).

As stated above, RPE adjusts to the needs of children who have suffered traumatic events, since the activities taking place are not done through a dialogue-mediated cognitive process, but through the motor and sensory functions that are the focus of the plastic approach (Steele & Raider, 2001). According to our observations and references made by the participants, the RPE utilized in the present study allowed the children to remember and express the traumatic events in a non-verbal manner, keeping a certain distance from those events when depicting them outside their minds and in a safe environment. Indeed, children felt free to fearlessly express their memories, thoughts, and emotions, which corroborates previous findings (Llanos Alonso, 2010). To summarize, RPE gave way to an uninhibited exposition and expression, allowing the subsequent overcoming of the traumatic material (with EFT).

Furthermore, the fact that RPE was conducted in groups contributed to the recovery process by providing children with a channel of communication in front of other people; who in turn represent the society they belong to. This process put an end to the invisibility of the painful event, thereby overcoming the barriers of silence and making it possible to reach a conclusion in front of other peers as well as facilitators. This also substantiates previous reports (Cury Abril, 2007).

Alternatively, recreation may be used therapeutically in two ways. The first approach deals with directly increasing the psycho-social well-being while diminishing anxiety and improving the mood (Vella, Milligan, & Bennett, 2013). The second deals with its playful nature, in this manner facilitating the implementation of therapeutic strategies in either an individual or group form (Trejos Parra, Cardona Giraldo, & Cano Echeverri, 2005b), both being demonstrated in the current research, where recreation provided comfort and facilitated the implementation of the psychotherapeutic program.

As suggested in Stumbo and Peterson (2000), the therapeutic recreation comprises three components: (1) the functional intervention, which focuses in the correction of the difficulties that people have; (2) the educational one, which implies the acquisition of new understandings, attitudes, and skills in regard to human and social development; and (3) the involvement, which allows the practice of the knowledge acquired in the two aforementioned components (Stumbo & Peterson, 2000). In the current study, a therapeutic intervention was implemented in order to mitigate the PTSD, by facilitating the learning of new and effective ways of confronting traumatic memories (EFT with RPE), thus children were able to practice such components by EFT along with a plastic program. In this manner, children acquired the tools to face the painful memories without avoidance, which could bring about the ongoing recovery from PTSD.

EFT has "the potential of desensitizing patients with PTSD without requiring them to fully engage in a verbal reliving of the traumatic experience" (Kolk, 2000), in which a great number of investigations, both randomized and controlled, EFT indicates its effectiveness in PTSD management, by means of only a few sessions (Church, 2013).

As mentioned earlier, exposure to the traumatic memory is a key component in treatments accepted for PTSD. Indeed, once this exposure is repeated without the negative consequences previously experienced, the distress response decreases. However, the approach can only be effective by means of prolonged exposures and when it recalls the complete sequence of the traumatic material. Additionally, the exposure does not affect the complex emotions processed by the cerebral cortex, such as guilt, which requires use of the cognitive restructuring. In contrast, the EFT has demonstrated its effectiveness without prolonged exposure, without a fixed focus on the complete sequence of the traumatic event (but on associated thoughts, feelings, or emotions) and in regard to the elaboration of complex emotions. Based on early neuroimaging studies, EFT appears to inhibit the hyperarousal of the amygdala, which, as stated before, plays a crucial role in the onset of PTSD. Consequently, this facilitates the processing of the traumatic memory by the hippocampus and the medial prefrontal cortex (Feinstein, 2010).

In this study, children worked during the recreational plastic expression, three rounds of EFT (that lasted 2 minutes each) approximately every 10 minutes. A rapid decrease in the intensity of the negative emotions was observed, and maximum levels were reached at the beginning of the session (10/10 on a Subjective Unit of Distress Scale-SUDS) which diminished or erased the negative emotions to the lowest level at the end of the same session. Likewise, the initial levels in the subsequent sessions started decreasing and the intensity of the symptoms decreased in a significant manner in six sessions, as corroborated by the statistic results. In contrast, the duration of the sole art-therapy programs tended to be longer (Eaton, Doherty, & Widrick, 2007).

Finally, traumatic events can make children lose vision of a safe and predictable world. Therefore, "not thinking about the future" is one of the symptoms encountered in children with PTSD (García Renedo, 2008). This symptom was clearly observed in the present study. However, it was also observed that, as children were working on their painful memories, they also began to think about their future lives. Indeed, by the last session of the program, giving a thought to a life project became possible without any effort, which was manifested during the implementation of RPE.

It can be concluded that EFT with RPE Program significantly decreased the presence and level of PTSD in school-age children boarded for abuse, in contrast with the control group. Interestingly, children in the control group also improved, but to a lower extent, probably because of the environmental changes including the protection of their rights, the recovery of untreated PTSD in a certain percentage of people and a lesser, unwelcome application of EFT in the control group. The Plastic Expression was found to be an adequate therapeutic approach in mistreated children, given the incomplete developing verbal skills and the hypo-activation of the post-traumatic stress speech area; besides, it allowed maintaining a distance from the traumatic memories by transferring them into objects outside of themselves and in a safe, group-oriented environment, facilitating the overcoming of the trauma. The Recreational environment provided psychosocial comfort, which decreased anxiety and improved the mood, thus helping to counteract avoidance, which is associated with the onset and maintenance of PTSD. The EFT provided a great decrease in the distress response, thus contributing to the suppression of avoidance, and facilitating the elaboration of the traumatic memory, including the cognitive restructuring. In contrast, this restructuring has not been observed following alone exposure to the traumatic event. The EFT with RPE Program allowed children to consider a life project, which was being avoided by the presence of PTSD.

This study had two limitations. One was the low number of participants, because it was required to work in small groups, and the short stay of many children in the protection institutions. The other [limitation]is that the œntinuity of the benefit of therapy over time was not measured, which does not allow to establish whether it was temporary or permanent. Therefore, more investigation is needed in the future in order to corroborate these findings and evaluate the efficacy of these therapeutic strategies using a greater number of sessions and follow-up for several months.