Introduction

In the context of dating, the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) gives the opportunity to maintain instantaneous contact and to strengthen the affective bond, but they also could be used for aggressive behaviors, control and domination over a partner, without the spatial-temporal restrictions of the "real" contexts (Caridade et al., 2019; Caridade & Braga, 2020; García-Sánchez et al., 2017; Machado et al., 2022). Cyber dating abuse or cyber dating violence (CDV), consists of the perpetration of behaviors intended to intimidate, control, monitor, humiliate, and attack a partner, through the use of technological devices (Borrajo et al., 2015a; Caridade et al., 2019; Cava et al., 2020; Machimbarrena et al., 2018; Rey, 2022; Thulin et al., 2020). CDV includes hostile and intrusive behaviors, humiliations or embarrassing behaviors, and the exclusion or blocking from social media, as well as sexual violence behaviors, such as pressuring or threatening the partner to send photographs with sexual content (Bennett et al., 2011; Hinduja & Patchin, 2020; Watkins et al., 2020; Zweig et al., 2013).

The statistics of the CDV prevalence studies point out that this issue could affect an important number of adolescents and young adults (Galende et al., 2020; Hinduja & Patchin, 2020; Machado et al., 2022; Smith et al. 2018; Stonard et al., 2014). A review of the literature carried out on 44 studies about CDV, most of which were carried out in the United States and to a lesser extent in others countries like Spain and Mexico, found prevalence rates which ranged from 8.1% and 93.7% for perpetration and between 5.8% to 92% for victimization (Caridade et al., 2019). These statistics claim the need to identify the circumstances that should be intervened in different contexts, to prevent the perpetration of CDV among adolescents and young adults, the population that most uses ICTs and have a higher risk for dating violence -DV- (Caridade et al., 2020; Galende et al., 2020).

Regarding the differences by sex in the prevalence of CDV, the results of the studies are contradictory, since while some report differences (e. g., Van Ouytsel et al., 2020; Zweig et al., 2013), others do not (see: Caridade et al., 2019; Machado et al., 2022). Zweig et al., for example, found that a significantly higher percentage of women had exercised CDV, both sexual and nonsexual, among 3745 American adolescents, while Van Ouytsel et al. found that be woman increasing the risk of perpetration between 466 Belgians from 16 to 22 years.

An important dimension of behavior that would make it possible to examine the differences by sex in CDV is the frequency of the behaviors perpetrated. However, with the exception of the study by Reed et al. (2018), who found among 703 American high school students that women performed some types of CDV more frequently than men, no further research on the subject can be found in the specialized literature.

Regarding the variables related to perpetration, a review of the literature revealed that the legitimization of CDV among adolescents, jealousy, romantic myths, sexist views, gender stereotypes, negative childhood experiences, and exposure to family conflicts could be associated literature (Caridade et al., 2019). Among adolescents or young adults, a relationship has also been found between perpetration with the justification of CVN behaviors and myths about romantic love (Borrajo et al., 2015b), the perpetration of bullying and norms of violence of male against female adolescents (Peskin et al., 2017), the problematic use of the internet and cyberbullying (Peña et al., 2018), anxious attachment (Toplu-Demirtaç et al., 2022), as well as being older, the perceived social norms of peers, the endorsement of gender stereotypes, and having observed intrusive controlling behaviors by the father (Van Ouytsel et al., 2020). Although these studies represent an advance in the understanding of CDV perpetration, their number is still low and most of them have been carried out with samples of less than a thousand participants (Caridade et al., 2019; Caridade et al., 2020; Curry & Zabala, 2020).

There is evidence that indicates that young people who inflict traditional DV have a higher probability of committing CDV (Caridade et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2018; Stonard et al., 2014). In this way, Zweig et al. (2013) found that who perpetrated sexual abuse through electronic means presented a probability 16 times higher of sexually coercing their partners, compared to those adolescents who did not carry out CDV. Since psychological DV includes behaviors such as coercion, humiliation and control, it has been considered that the perpetration of traditional DV could associate or predict CDV, given that the CDV includes frequently behaviors of psychological violence as control, coercion and aggressions carried out by electronic means (Reed et al., 2018; Temple et al., 2016). Consistent with the above, Lara (2020) informed high and moderated correlations between CDV perpetration and coercion, emotional punishment, instrumental violence, detachment and humiliation, in 1538 Chilean adolescents and young adults. However, there are no studies that examine whether traditional DV increases the risk of CDV perpetration.

Other variable that could increase the risk of perpetration is CDV victimization, since some investigations have found high prevalences of both perpetration and victimization in the samples under study (Lara, 2020; Redondo, Luzardo-Briceño et al., 2017), and the bi-directionality is very frequent in prevalence studies of traditional DV (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017; Wincentak et al., 2017; e. g., Young et al., 2021). According to Young et al. (2021), the bi-directionality in DV may reflect a normalization of violence in relationships, so interventions should focus on promoting healthy relationships and not so much on supporting the victim or modifying the offender's behavior, which would be the case if the violence were unidirectional. These researchers found in a nationally representative sample of Welsh, that bi-directionality tended to be high in relation to emotional violence and less so in relation to physical violence. Given that, as already mentioned, CDV involves many behaviors of psychological violence, it is to be expected, in light of what these authors found, that the risk of perpetration increases with victimization. In that sense, Cava et al. (2020) found that victimization significantly predicted the perpetration of CDV in a sample of 492 adolescents from Spain. Nevertheless, there are no other studies on the increased risk of perpetration due to victimization.

The studies carried out in Colombia concerning the prevalence of DV indicate that this problem could take place among a high percentage of adolescents and young people (e. g., Martínez et al., 2016; Redondo et al., 2017; Rey et al., 2022). To date, only one study has been published concerning CDV involving 639 university students (age mean: 17.66 years), of which, 27.5% reported having been aggressed through ICTs on some occasion during the year prior to the study, while 26.7% informed having committed the same type of violence during this period (Redondo, Luzardo-Briceño et al., 2017). According to the TICs Colombian Ministry (Ministerio de Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones, 2023), in the country there are more than 79 millions of mobile phones subscribers, with a population of 55 millions approximately. Therefore, it is possible that CDV affects a significant number of Colombian adolescents and young adults. However, in this country no studies have been conducted about the differences by sex in the prevalence and frequency of CDV, and the potential variables that could increasing the risk of perpetration, which would permit the outlining of valid strategies for its evaluation, intervention, and prevention.

The prevalence figures of CDV call for the need to examine the variables that could be related to the perpetration, with DV victimization and psychological DV perpetration being two variables that the results of some studies indicate could be related. Therefore, it would be worth examining them in order to establish intervention and prevention strategies based on evidence. On the other hand, in Colombia there is a lack of studies on these variables and an absence of published studies on the differences by sex in the prevalence and frequency of CDV, which make it possible to determine if this problem affects women and men differently in adolescence and youth, in order to establish care and prevention strategies for this problem that take these differences into account.

Based on the above, this research proposed as objectives: (a) To compare the prevalence and frequency of CDV by sex in a sample of Colombian adolescents and young adults, and (b) to explore the relationship between CDV perpetration with CDV victimization and the perpetration of psychological DV.

Method

Design

According to Méndez and Nahimira (2000), this study implemented a non-experimental, cross-sectional and comparative design.

Participants

The participants were 2023 adolescents and young adults: 1072 women (53%) and 951 men (47%). They live in Bogotá, the capital of Colombia (n =1000) and Tunja, in the department of Boyacá (n =1023). From the total, 74.7% (n=1511) of the participants were adolescents (between 13 and 19 years of age), while the remaining 25.3% (n =512) were young adults (between 20 and 40 years of age), with a mean age of 17.92 years (SD=3.6). With regard to sexual orientation, 92.3% (n =1868) reported being heterosexual, while 5.4% (n =109) considered themselves to be bisexual and 2% (n =40) homosexual (six participants did not give any information regarding this point). From the participants, 61% (n =1234) were between eighth and eleventh grade, in six secondary education institutions of Bogotá and Tunja, while 39% (n =1234) of the participants were doing their bachelor and undergraduate degrees in Tunja. The participants declared having had a mean of 4.17 sentimental relationships (SD =4.31), with an average duration time of 11.65 months (SD=19.1) with the current partner and 9.48 months with the previous (SD=12.11). According to the classification of the National Administrative Department of Statistics, the participants live in sectors of socioeconomic level: low-low (n =416, 20.6%), low (n =1011, 50%), medium-low (n =472, 23.3%), medium (n =100, 4.9%), and medium-high (n =16, 0.8%; eight participants did not give this information).

The inclusion criteria were the following: (a) being between 13 and 40 years of age, (b) being unmarried, (c) being in or having had a sentimental relationship, and (d) having the written consent of the parents and of the adolescent (except for those of legal age). Therefore, the exclusion criteria were: (a) having an age outside the mentioned range, (b) being married or in a free union, (c) not having had a sentimental relationship and (d) not having the written consent of the parents and of the adolescent (or that of the latter, if he/she was of legal age). The sampling was not probabilistic for convenience, according to the availability of the participants in the institutions.

Instruments

Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (CDAQ ;Borrajo, Gámez- Guadix, Pereda et al., 2015)

This questionnaire allows to reports the perpetration and victimization of direct aggressions and monitoring/controlling behaviors made by electronic means during the last year, through 20 pairs of parallel items which are answered with a Likert scale of six options: (1) Never, (2) Not in the past year, but it has happened before, (3) Rarely: once or twice, (4) A few times; between 3 and 10 times, (5) Usually: between 10 and 20 times, and (6) Always: more than 20 times. The factor of direct aggressions include behaviors such as publishing or sending messages and other humiliating or embarrassing content, as well as threatening the partner with the same (example: "My partner or ex-partner has threatened me through new technologies to physically harm me", "I have threatened my partner or ex-partner through new technologies with physically hurting him/her"). Whereas, the factor of monitoring and controlling behaviors include checking the partner's phone, as well as his/her messages and publications on social media, or calling insistently to know where he/she is and with whom (example: "My partner or ex-partner has checked my social networks, WhatsApp or email without my permission", "I have checked my partner's social networks, WhatsApp or email without his/her permission"). The authors of CDAQ reported satisfactory rates of content, construct and convergent validity, based on the data provided by 788 Spanish people between 18 and 30 years of age, obtaining alpha which range between .73 and .87.

The instrument was validated with 2023 Colombian adolescents and young adults (Rey et al., 2021), carrying out some adjustments with the aim of adapting it to standard Spanish, given that there were some terms and expressions of common use in Spain, which may not have been understood by the participants, presenting a alpha of .84 for the scale of perpetration and .87 for the scale of victimization. The confirmatory factor analysis showed satisfactory adjustment indexes for the original structure of the instrument and its scales correlated significantly with measures of psychological DV.

Checklist of Experiences of Psychological Abuse to the Couple (CEPA;Rey et al., 2019)

This checklist allows report 14 behaviors of coercion, humiliation and control committed in the past 12 months, through a Likert scale of four options: Never (0), Once (1), A few times (3) and Many times (4). Examples of items: "You threatened to take her/him to a mental institution", "You criticized her/his physical appearance -being fat, thin, etc.-", and "You watched her/him in her/his place of study, work, or another different space". The instrument was validated with 1729 Colombian males and females, between 12 and 42 years of age, obtaining an alpha of .85. The scale showed appropriate adjustment rates and correlated significantly with personality trait scales associated with gender. With the sample of this study a general alpha of .72 was obtained.

Procedure

The authorization of several educational institutions of secondary and university education in Bogotá and Tunja was requested to invite their students to study, obtaining authorization from eight of them. After the study was authorized by these institutions, the students were contacted in their classrooms according to their availability to request their informed consent, or their permission and the informed consent of their parents, in cases where they were under aged, for which a form was given to them with the following information: the objectives and the methodology of the study, their anonymity, the confidentiality of the information obtained, the autonomy of the research with respect to the institution, the voluntary nature of participation, and that the decision to withdraw during the course of the research would be respected without any legal or social consequences. In order to counteract social desirability, in addition to the anonymity in the responses to the questionnaires and the confidentiality of the information, in this form the participant was asked to commit to "answering honestly so that the investigation yields valid results". They were also guaranteed that their identification data would not appear in the report, presentation or academic publication of the study and that the data collected would only be used for research and academic training purposes, in conformity with the legal norms that regulate scientific research in Colombia.

Afterwards, the instruments were applied to the group, checking that all the items were answered. The participants were not remunerated for their collaboration. However, they were offered the possibility to receive the results obtained from the instruments, if requested. The data were collected in 2019, within the framework of a project endorsed by the ethics committee of the funding institution.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained were systematized in an SPSS database version 26.0, which were revised in order to identify and correct errors in the data collection, implementing the following statistical analyses: (a) Chi Squared test and Odds Ratio (OR) to compare the percentage of women and men who reported the perpetration of at least a CDV behavior, leastways once o twice in the past year ("Rarely"), (b) the same statistical analyses to compare the percentage of participants that perpetrated and not perpetrated at least a CDV behavior, leastways "Rarely", and informed have suffered at least a CDV behavior leastways "Rarely" and reported have perpetrated at least a psychological DV leastways once in the past year, (c) T-test independent samples to compare the frequency of CDV behaviors between women and men, both overall and by factor, and (d) multiple linear regression, taking as dependent variable the frequency of CDV behaviors perpetrated and as independent variables the frequency of CVD behaviors suffered and the frequency of psychological DV perpetrated.

Results

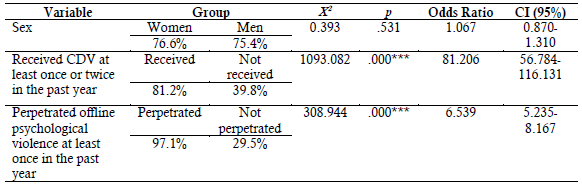

The 87.5% (n=1770) of the participants reported having perpetrated at least one behavior of CDV selecting the option: "Not in the past year, but it has happened before", not finding a statistically significant difference between the percentage of women and men who informed this circumstance (women: 88.1%; men: 86.9%; X 2 [1, V=2023]=0.667, p=.414, OR=1.116, IC: 0.857-1.453). While, the 76% (n=1538) of the participants informed having perpetrated at least one behavior of CDV once or twice in the last year, not finding a statistically significant difference between the percentage of women and men who informed that frequency (see Table 1).

The probability of perpetrating a CDV behavior (at least rarely) was 81 times higher between the participants who received CDV at least once or twice in the past year, than participants that no, and six times higher among participants who reported having committed psychological DV at least once in the past year, that among participants no informed that perpetration (see Table 1).

Table 1 Percentage of Participa«ts who Reported a«d Not Reported Having Perpetrated CDV at Least Rarely a

Vote. CDV: Cyber dating violence; X 2: Chi Square value; p: Significance; CI: Confidence interval.

a Once or twice in the past year.

***p <.001

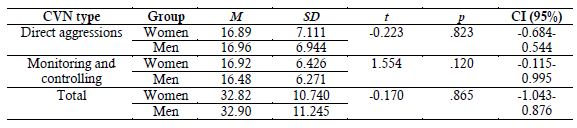

No statistically significant differences were found by sex regarding the frequency of perpetration of CDV behaviors at a general level, neither in the direct aggressions factor nor in the monitoring and controlling behaviors factor (see Table 2).

Table 2 Differences Between Women and Men in the Frequency of CDV Behaviors Perpetrated

Note. CDV: Cyber dating violence. M: Mean; DS: Standard deviation; t: Value of T-test; p: Probability; CI: Confidence interval.

The multiple linear regression analysis reveals that the frequency of CVD behaviors suffered (B=.736; p=.000) and the frequency of psychological DV perpetrated (B=. 113; p=.000), explained 62.6% of the variance of the frequency of CDA behaviors perpetrated: F (2, 2023) = 1690.104, p=.000, Adjusted R 2 = .626.

Discussion

The objectives of this study were to compare the prevalence and frequency of CDV by sex in a sample of Colombian adolescents and young adults, and to explore the relationship between CDV perpetration with CDV victimization and the perpetration of psychological DV. The results indicate a high prevalence of adolescents and young adults perpetrating CDV among the Colombian population, and, therefore, the advisability of continuing to investigate this problem and generate alternatives for its evaluation, intervention, and prevention.

It was also found that the prevalence and the frequency of CDV were similar between men and women, unlike previous studies (Reed et al., 2018; Van Ouytsel et al., 2020; Zweig et al., 2013), suggesting that the research and intervention of this form of cyberviolence in Colombia should target the youth population regardless of gender. In this sense, Reed et al. consider that beyond the sex of the perpetrator, social stereotypes about gender and dating relationships play a more preponderant role in CDV. Therefore, the beliefs that justify control behaviors through ICTs and that normalize aggression by these means should be examined, so they support the design of different prevention strategies for this problem.

The results also indicate that the risk of committing CDV is significantly higher when at least one psychological DV behavior was perpetrated in the last year, results which are consistent with those obtained by Cava et al. (2020), who found that offline DV significantly predicted CDV. These results indicate that a person who inflicts traditional DV has a higher probability of exercising CDV and supports the idea that CDV is an extension of traditional DV, particularly the psychological (Borrajo et al., 2015a; Duerksen & Woodin, 2019; Caridade et al., 2020; Jaen-Cortés et al., 2017; Stonard et al., 2014; Temple et al., 2016). Therefore, at the level of prevention, it is not necessary to make distinctions on the type of DV (traditional or online), but campaigns should focus on DV in general (Reed et al., 2018). However, the high prevalence of CDV found in this study and in others (see Caridade et al., 2019), indicate that it is convenient to include in the prevention campaigns strategies, methodologies and components that focus on the cyberviolence, such as education on the proper use of ICTs and what to do the victim of this type of violence (Machimbarrena et al., 2018).

The results also show a close relationship between CDV victimization and perpetration, because the victimization increased 81 times the risk of perpetration. A high bi-directionality has been noted in offline DV (Rubio-Garay et al., 2015; Wincentak et al., 2017), and it is possible that victimization and perpetration are the two sides of the same coin, in the sense that those who exercise DV also receive it, because she/he has beliefs that justify and normalize aggression in dating relationships. It is also possible that whoever suffers this type of violence at some point ends up exercising it, since it ends up being accepted as a normal pattern of the relationship (Young et al., 2021). Therefore, timely detection and intervention of CDV victims would constitute a valid alternative to prevent perpetration. It is worth noting that justification and myths about romantic love have been linked to CDV (Caridade et al., 2019), hence it is recommended to examine in depth the myths and beliefs that justify and normalize this form of cyberviolence, as well as the effectiveness of interventions focused on promoting healthy relationships in the victimization and perpetration of CDV.

The previous findings are supported by the results of the multiple regression analysis, which indicate that the frequency of victimization and the frequency of perpetration of psychological DV significantly predict the perpetration of CDV, similar to that reported by Cava et al. (2020) and Lara (2020). Therefore, an increase in the perpetration of CDV could be expected if the frequency of victimization increases, among adolescents and young adults in whom aggressive patterns of partner interaction have been established. Likewise, an increase in the perpetration of psychological DV would predict an increase in the perpetration of CDV, probably due to the essentially psychological nature of the latter, extended to virtuality scenarios (Reed et al., 2018; Temple et al., 2016). In this way, it should be expected that an adolescent or young person who has exercised psychological violence against her partner will extend this form of violence to this type of scenario as the frequency of perpetration increases.

In summary, the results suggest that CVN detection and prevention campaigns should focus in both men and women, particularly those who have suffered this form of violence and have exercised traditional DV. Given the relationship between offline and online DV, these prevention campaigns should be carried out for DV in general, although considering specific aspects for CDV, such as the proper use of ICTs, if it is also considered that the youth population massively uses these media to manage their social relationships (Galende et al., 2020). However, more research is required to account for the possible role of other variables not examined previously, such as the influence of peers, and the beliefs, attitudes and knowledge about the use of ICTs, among other (Machado et al., 2022; Machimbarrena et al., 2018).

The following are some of the strengths of this investigation: the size of the sample, the participation of adolescents and young adults, and the use of different statistical tests that allowed comparing their results. Notwithstanding, this study was transversal and it not examined the sexual CDV, on which there could be differences by sex in terms of prevalence and risk factors, limitations that should be contemplated in future investigations.