INTRODUCTION

Brucellosis is an infectious disease caused by a facultative intracellular pathogen that belongs to the genus Brucella; it is part of the 2α class of the Proteobacteria, whose members share the ability to interact intracellulary with the eukaryotic cell (Moreno et al. 1990; Paulsen et al. 2002; Chain et al. 2005; Ficht, 2010).

For many years, this genus comprised only six species, denoted the classical brucellae: B. melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis, B. canis, B. ovis and B. neotomae (Allardet-Servent et al. 1988; Vargas et al. 2011; Scholz & Vergnaud, 2013; Skendros & Boura, 2013). Mainly differentiated by their host preference and a set of antigenic and phenotypic characteristics. Since the 90’s four Brucella species have been isolated from marine mammals, rodents and surprisingly from a breast implant (Paulsen et al. 2002; O’Callaghan & Whatmore, 2011; Vargas et al. 2011; Ortega et al. 2013; Wattam et al. 2014). Other studies have reported the isolation of novel Brucella species denoted Brucella vulpis (Hofer et al. 2012; Scholz et al. 2016) and Brucella papionis (Whatmore et al. 2014) that belong to the atypical group of Brucella (Tiller et al. 2010), and other isolates from frogs, fish and additional rodents thus expanding the type of host of this bacterium (Eisenberg et al. 2012; Eisenberg et al. 2016; Scholz et al. 2016; Soler-Lloréns et al. 2016; Whatmore et al. 2016).

In relation with the genetics of this pathogen, in 1985 a high degree of identity (>90%) among Brucella species was found from studies made by DNA-DNA hybridization between the different species (Gee et al. 2004), which made them difficult to classify. Since then, a consensus has been reached about the grouping of the Brucella species by different authors, given that the results depend on the techniques, the number of strains used, and the inclusion of new species as well as the method of phylogenetic analysis used. The aim of this review was to compare from a methodological point of view, the Brucella species that are most widely studied and among which phylogenetically clear relations are presented.

METHODS

The study includes a comprehensive search in electronic databases. A literature review was conducted with the following key words: Brucella, evolution of Brucella, phylogenetic of Brucella, classification of the genus Brucella, methods for classification of Brucella, species in Brucella and the combination of these terms. Records ranged from 40-50 articles, and articles published in English and Spanish were identified, classified and analyzed. Articles that provided relevant information on the basis and subject of the review were selected, the period considered in the research was from 1985 (first publication about Brucella genus) to 2016. Items whose thematic is not related to evolution or typification techniques were excluded

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Regarding the phylogenetic relationship of Brucella species, a consensus about the grouping of the different Brucella species is shown:

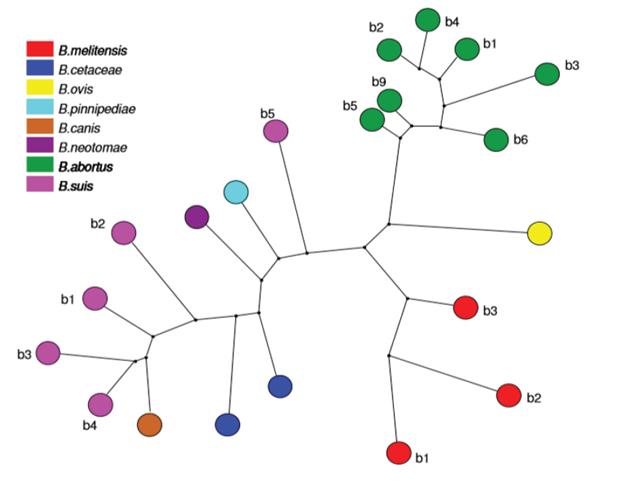

Brucella abortus and Brucella melintesis: The phylogeny for these two species depends on factors such as type and number of species included in the analysis, as well as the technique and methodology used. In this classification, many authors have disagreed on through the years, the current consensus from the comparative study of the Brucella species through variations in the Omp2 gene sequences up to the last analyses realized from SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) (Vignal et al. 2002; Ohishi et al. 2008; Wattiau et al. 2011) and of orthologous proteins, considers Brucella melitensis and Brucella abortus as part of a monophyletic group (Figure 1) (Mirnejad et al. 2012; Wattam et al. 2014). When we carried out phylogenetic analyzes, through the analysis of housekeeping genes including O. anthropi as an external group, showed B. abortus and B. melitensis as sister species, each of them monophyletic (Arboleda et al. 2017)

Figure 1 Phylogenetic analysis based on maximum parsimony from SNPS (Wattam et al. 2014). All branches have 100% support unless otherwise noted, which permits restricted use. License number 3798391155478.

Complete genome sequencing is ideal; they have the advantage that mutational changes are totally reflected in the sequence, an event that does not occur in proteins, due to the degenerate character of the genetic code; clarifying in this way the main evolutionary mechanims involved in the different processes of speciation, an example of this type of study was made in 2015 in where the authors sequenced the complete genome of several B. melitensis strains, achieving not only discrimination between vaccine and endemic species, but also performing a phylogenetic reconstruction of the history of the species and proposing a possible global distribution of the bacterium (Whatmore et al. 2005; Tan et al. 2015).

Brucella suis and Brucella canis: In relation to these two species, it has been particularly difficult to distinguish among them because of the few genetic polymorphisms allowing to discriminate them at the molecular level (López-Goñi et al. 2011). Ficht et al. (1996) identified variations in the sequences of the gene that codes for the Omp2 protein, this membrane protein linked to the formation of porin, could be used for the differentiation of species given the high degree of sequence conservation (Ficht et al. 1990). Phylogenetic analyses postulated a recent divergence and a close relationship between these two species, proposing them as sister taxa with a common ancestor that is not shared with other species of Brucella (Whatmore et al. 2005).

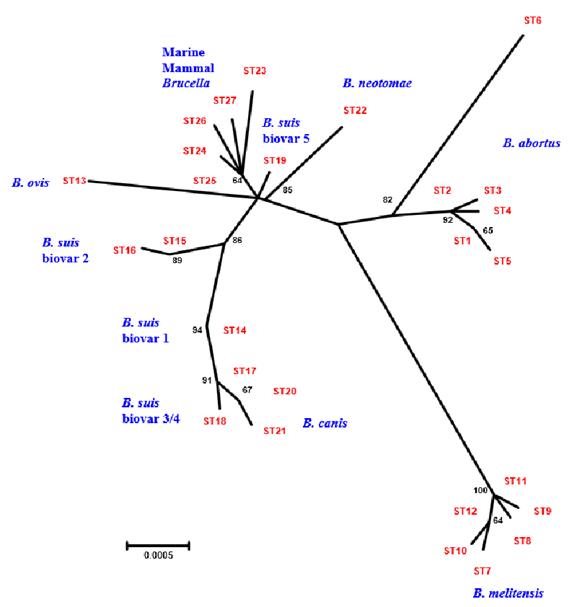

With the use of techniques such as AFLP (amplified fragment length polymorphism) (Meudt & Clarke, 2007), MLEE (Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis) (Selander et al. 1986) and orthologous proteins, it is not possible to differentiate these two species and hence their limited use as tools (Gándara et al. 2001; Whatmore et al. 2005; Wattam et al. 2009) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Dendogram from multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (Gándara et al. 2001), which permits restricted use. License number 3798390614711.

Techniques such as MLVA (Multilocus variable number of tandem repeats analysis), VNTR (variable number of tandem repeats) (Al Dahouk et al. 2007) and MLST (Multilocus sequence typing) (Maiden et al. 2013) show a clear dispersion between different strains of the same B. suis species (Figure 3), where the greatest distance is found between biovar 5 and the other biovars. Additionally, it exposes the separation of B. suis into two subclades, one formed by the biovar 2 and one that contains biovars 1, 3 and 4, making this species a paraphyletic group (Wang et al. 2016), converting it into the most diverse strain of this bacterial genus (Le Flèche et al. 2006; Sankarasubramanian et al. 2016). This research also shows the direct emergence of B. canis from a B. suis ancestor (Figure 2) (Le Flèche et al. 2006).

Figure 3 Phylogenetic analysis based on maximimum parsimony from MLVA (Le Fléche et al. 2006), which permits unrestricted use.

In our 2016 research, in which B. suis is observed as the species with the greatest genetic diversity among the strains studied; and the proximity between B. suis and B canis is observed, forming part of the same clade, with low divergence (Arboleda et al. 2017).

Brucella ceti and Brucella pinnipedialis: Referring to these two species, the first one was isolated from porpoises, whales and dolphins while the second one was isolated from common seals (Gándara et al. 2001; Foster et al. 2007). It is from these reports that the largest number of isolates have been reported and the host range has been significantly expanded (Verger et al. 1985). Since their discovery, the marine Brucella strains have been subjected to a range of tests such as DNA-DNA hybridization and ribotyping, in order to compare them with the terrestrial strains (Verger et al. 2000).

The first inclusion of marine species in the phylogeny of Brucella was made by Jensen et al. (1999), where an unusual grouping between these was demonstrated, similar to what was found between Brucella canis and Brucella suis serotype 1 (Michaux-Charachon et al. 1997). The ones isolated from the marine mammals presented different profiles from the other species of Brucella, placing them in a different clade or branch of the tree (Figure 1, Figure 4) (Whatmore et al. 2007).

Figure 4 Phylogenetic analysis based on concatenated sequences through neighbor joining (Whatmore et al. 2007), which permits unrestricted use.

Based on studies of the Omp2 gene polymorphisms these authors proposed two subdivisions, recognizing two marine species, Brucella pinnipediae isolated from seals and Brucella ceti isolated from dolphins and porpoises (Cloeckaert et al. 2001), while other authors, through techniques such as VNTR, MLST, Fingerprint, demonstrated the separation of the marine species into three isolated groups (Le Flèche et al. 2006; Whatmore et al. 2006; Dawson et al. 2008): the first was obtained from species of dolphins, the second consisted in strains isolated from porpoises and the third contained isolates of different seal species (Groussaud et al. 2007; Dawson et al. 2008; Sidor et al. 2013). From these studies we retained the subdivisions within the B. ceti species because of their host preference between dolphins and porpoises. In a similar manner we speak of an ecological subdivision between the members of the pinnipediales species, demonstrated by a subgroup of hooded seals (Dawson et al. 2008).

Two groups have been agreed on based on more specific techniques: B. ceti and B. pinnipediales, with very small genetic distances, indicating a simultaneous divergence (Wattam et al. 2014); however it does not match the phylogeny of its main host. Guzmán-Verri et al. (2012) discusses the ability of the Brucella species to jump from one host to another and in some cases to generate new species depending on their preferred host, but they are in no case closely related with the divergence time of the host species, assuming a contamination of the marine species by the food chain (Dawson et al. 2008; Guzmán-Verri et al. 2012).

Brucella ovis and Brucella neotomae: Since the initial studies on the phylogeny of Brucella, B. ovis and B. neotomae species have been reported as the most divergent (Ficht et al. 1996; Michaux-Charachon et al. 1997; Jensen et al. 1999; Wattam et al. 2009), these data have differed depending on the techniques used and the inclusion of one or two species in the same analysis, placing these two species in the same clade is influenced by the used technique.

To define the basal or the most divergent species, different techniques have been proposed: the first one with MLVA, MLST and orthologous protein (protein in different species that connected through vertical evolutionary descent) (Fitch, 1970), where the authors confirm the previous divergence of B. ovis forming a separate clade from the other Brucella species (Le Flèche et al. 2006; Whatmore et al. 2007; Wattam et al. 2009) corroborated with the SNP orthologous study, suggesting that brucellosis in animals such as pigs, goats and cattle occurred from contact with infected sheep, approximately in the last 86.000 to 296.000 years (Foster et al. 2009; Yang & Rannala, 2012). Our phylogenetic analysis, including O. anthropic as an external group yielded results according, placed B. ovis as the first lineage to be divided from the rest of the species of Brucella and recognize it as the basal species (Arboleda et al. 2017).

The second species, B. neotomae reported by Audic et al. (2011), from the analysis of the orthologous genes and the inclusion of a greater number of species, showed an initial divergence from B. microti and after this event the divergence of B. suis and B. neotomae demonstrated by the loss of a 2.6 kb fragment from these two species (Wattam et al. 2009; Audic et al. 2011).

Brucella of early divergence: Throughout the years and with the advances in molecular analysis, new species of Brucella have been discovered, this causes variations in phylogenies (Audic et al. 2009; Whatmore et al. 2016) sequenced and examined the phylogeny of MLVA based on VNTRs from B. microti, initially isolated from voles, foxes and later from soils, being the only species with a reservoir outside a mammalian host (Rónai et al. 2015), contradicting the assumption that B. ovis is the most basal species and showing that B. microti is an even more basal species than B. ovis, also indicating that B. inopinata isolated from humans presents a previous divergence (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Phylogenetic reconstruction from 1,486 orthologous genes (Audic et al. 2009), which permits unrestricted use.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion there is a clear transition in the evolutionary tree of Brucella from its initial analysis 20 years ago, where a single species with multiple biodiversities was established (Foster et al. 2009). Phylogenetic studies have helped to see gene transfer events, thereby allowing not only the differentiation of the various Brucella species, but also the acquisition of virulence factors including the type IV secretion system, a perosamine based O antigen, and systems for the maintenance of metals and lineages involved in its host preference (Wattam et al. 2014; Tan et al. 2015).

The development of new studies to reach a better understanding of Brucella evolutionary history, host specificity and pathogenicity, is still needed to include a greater number of representatives genomes of each species, and to incorporate and to evaluate previous data (Moreno et al. 2002). Phylogenomics is the best alternative to ensure a better resolution to these questions, considering others speciation processes that can cause variations in the resulting trees (Eisen & Fraser, 2003) because it provides a direct way to estimate the evolution of the species from all the shared genes, and in which no duplication patterns or horizontal gene transfers are involved.

This review article demonstrates how molecular and bioinformatics advances have led to a better understanding of the genus Brucella, defining small but significant differences between species, which can be used to identify important interactions that contribute to the invasion, persistence, transmission and even virulence of each one of them.