INTRODUCTION

Ticks are ectoparasites of great importance in transmitting microorganisms to humans and animals (Parola & Raoult, 2001; Jongejan & Uilenberg, 2004; Labuda & Nuttall, 2004; Dumler & Walker, 2005). Ticks from the family Ixodidae, also known as hard ticks, are obligate ectoparasites of all kinds of terrestrial vertebrates; they can produce anemia and paralysis, but their primary importance is given by the fact that they are vectors of nematodes, viruses, bacteria, and protozoa (Guglielmone & Robbins, 2018). Forty-three species have been reported in Colombia belonging to the genera Amblyomma, Ixodes, Haemaphysalis, Rhipicephalus, and Dermacentor (Guglielmone et al. 2003; Rivera-Páez et al. 2018); these ticks are essential in the transmission of rickettsias of spotted fever group such as Rickettsia rickettsii, R. parkeri, R. massiliae, R. africae and R. conorii in America (Matsumoto et al. 2005; Parola et al. 2005). Ticks can be vectors by transmitting rickettsias across their bite but can also be reservoirs by the transstadial and transovarial passage of these bacteria (Bremer et al. 2005; Parola et al. 2005).

Rickettsiae are gram-negative, obligate intracellular coccobacillus bacteria. The genus Rickettsia has been classified into four groups: The spotted fever group (SFG), the typhoid group (TG) (Hackstadt, 1996), the transitional group (TRG) (Gillespie et al. 2007) and the ancestral group (Stothard & Fuerst, 1995). Phylogenetic relationships in this genus have been established by variability in genes coding for the enzyme citrate synthetase (gltA) and external surface antigens and proteins (sca1, sca2, sca4, ompA, and ompB) (Merhej et al. 2014).

Currently, tick-borne rickettsial diseases are recognized as zoonotic diseases, causing a febrile syndrome that can be present in 1.5-5.6 % of travelers to tropical areas and 2.7 and 48.5 % of residents of such places (Blanton, 2013; Merhej et al. 2014). Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Tobia fever in Colombia, Brazilian spotted fever in Brazil) produced by R. rickettsii can be severe, with case fatality rates between 7.3-100 % (Raoult & Parola, 2007; Nogueira-Angerami et al. 2009; Regan et al. 2015). In Latin America, cases of the disease have been described in Brazil (Labruna, 2009), Colombia (Hidalgo et al. 2007; 2011) and Argentina (Paddock et al. 2008). In Colombia, outbreaks with lethality between 26 to 36 % have occurred in departments such as Cundinamarca, Córdoba and Antioquia (Acosta et al. 2006; Pacheco-García et al. 2008; Hidalgo et al. 2011).

In 2012, in the northern area of Caldas, it was found that 5 out of 27 patients with febrile processes compatible with the rickettsial disease presented antibody titers against R. rickettsii; all patients showed a variation in the titer that ranged between 2 to 3 times its initial value in the samples taken during convalescence, which suggests that they were suffering from an active disease (Hidalgo et al. 2013). Given the findings mentioned above, the objectives of this study were to establish the frequency of vectors associated with rickettsiae of the SFG group and to detect and identify the species of rickettsiae present in ticks found in this region of the department.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

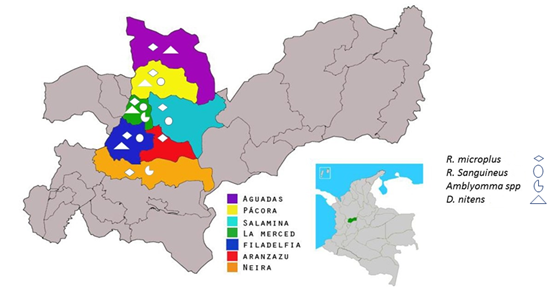

A cross-sectional, observational, and descriptive study was conducted in which convenience sampling was carried out in rural properties and the urban area of each municipality. The study area comprised the northern region of the department of Caldas, Colombia: Neira 5°09'46''N, 75°31'31''W, Aranzazu 5°16'18"N, 75°28'12"W, Salamina 5°23'15"N,75°29'41"W, Pácora 5°31'53"N, 75°27'20"W, Aguadas 5°36'07"N, 75°27'22"W, La Merced 5°23'35"N, 75°32'42"W and Filadelfia 5°17'33"N, 75°34'17"W) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Map of Caldas department of Colombia with the study area colored and ticks species localization.

Collection and identification of ticks. Ticks parasitizing equine, bovine, and canine individuals were collected between January and December 2015 in each municipality listed above. Ticks were carefully extracted with entomological tweezers to preserve the capitulum of the specimens. The individuals from each animal were stored in Eppendorf® tubes with 90 % ethanol, duly labeled. Data was obtained for each animal sampled, such as sex, age, breed, presence or absence of ectoparasites, date of tick harvest, municipality, place of sampling (urban or rural), altitude, and specific site of vector extraction. Tick morphological identification was carried out by visualization under a stereomicroscope (Euromex ref: stereoblue) and according to Jones et al. (1972), Barros-Battesti et al. (2006), Mehlhorn (2008), Martins et al. (2010) and Nava et al. (2014; 2017).

Molecular detection of Rickettsia spp. in ticks. Groups of eight ticks were formed, selecting the arthropods by species and municipality of origin. DNA extraction was performed using the commercial kit Ultraclean Tissue & Cells DNA Isolation Kit sample Cat. 12334-S (MO BIO laboratories) (MO BIO Laboratories, 2019). DNA was stored at -80 °C until amplification by conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

The citrate synthetase enzyme gene (gltA), common in all members of the genus Rickettsia, was amplified using primers CS78 and CS323, which amplify a fragment of 440 bp (Labruna et al. 2004). In the case of the presence of this gene, the ompA, ompB, and 17kD genes of this microorganism would be amplified to establish the Rickettsia species by sequence comparison. To verify the integrity of the DNA obtained, the primers of the tick mitochondrial 16 S rDNA gene (16S+1: CTG CTC AAT GAT TTT TTA AAT TGC TGT GG; 16S-1: CCG GTC TGA ACT CAG ATC AAG T) that amplify a fragment of approximately 463 bp (Black & Piesman, 1994) were used. Rickettsia parkeri DNA was used as a positive control, and ultrapure water was used as a negative control.

Amplification was performed using the Dream Taq Green DNA polymerase kit (Thermo Scientific®) according to the following protocols. For the gltA gene, denaturation at 95 °C for three minutes, followed by 35 amplification cycles with the following temperatures 98 °C for 20 sec, 56 °C for 15 sec and 72 °C for 60 sec, and a final extension at 72 °C for 60 sec (Labruna et al. 2004). Amplification of the 16S rDNA gene, was carried out with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 sec; 10 cycles with the following temperatures 98 °C for 30 sec, 48 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 40 sec; 15 cycles of 98 °C for 30 sec, 50 °C for 40 sec and 72 °C for 30 sec; 10 cycles at 98 °C for 30 sec, 55 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 40 sec and a final extension at 72 °C for seven minutes (Black & Piesman, 1994).

Statistical analysis. A descriptive study of tick infestation in the animals sampled was performed. To establish possible relationships between infestation, type of domestic animal, area of origin, and municipality, Pearson's Chi-square test was used, using Excel (Microsoft) and Epi-info (CDC).

Ethical aspects. To obtain the sample, the owner of the animal or the administrator of the farm was asked to sign an informed consent form; a survey was filled out with each animal sampled in which the demographic data mentioned above were obtained. The research project was submitted for review by the Bioethics Committee of the Universidad de Caldas, with the approval for the development of the project, by means of act 006 of 2014. The researchers involved in the development of the project are aware of the universal declaration of animal rights proclaimed by the International League for Animal Rights, Geneva, Switzerland, the guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (NRC, 1996) and the ethical principles of animal experimentation enunciated by ICLAS, International Council for Laboratory Animal Science.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

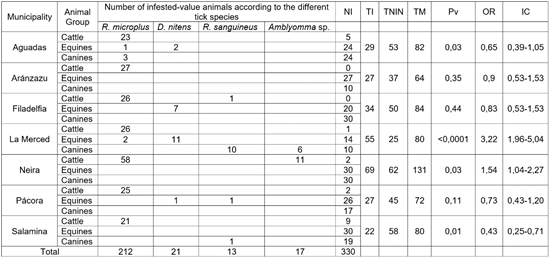

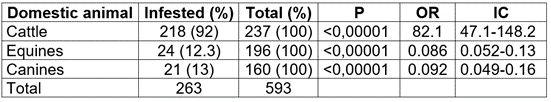

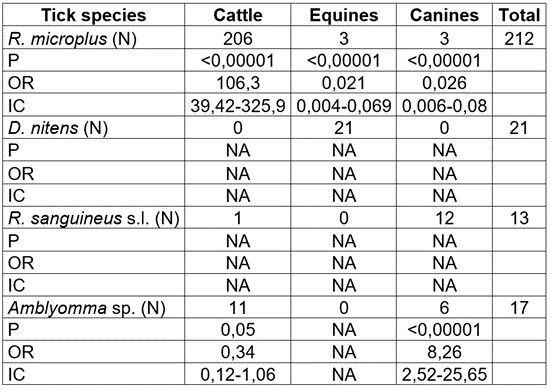

A total of 593 domestic animals were examined, collecting 713 adult ticks in the seven municipalities sampled (Table 1). According to the animal-tested, 40 % corresponded to bovines (Bos taurus), 33 % to equines (Equus caballus), and 27 % to canines (Canis lupus familiaris) (Table 2). Most of the animals were females (71 %) and came from rural areas (567 animals, 96 %). Of the total bovines, 92 % were infested, with high statistical significance (Table 2). The most frequently found tick species was R. microplus, followed by Amblyomma sp. and R. sanguineus (Table 3). The number of infested equines was low, corresponding to 12.3 % of the total number of animals in this group (Table 2). Unlike bovines, the most frequent tick species was Dermacentor nitens, found in 10.7 % of this group of animals (Table 3). Four of the seven municipalities had no infested equines, while Filadelfia and La Merced had the highest percentages of infestation, 25 and 44 %, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of ticks by group of domestic animals and municipalities in the northern region of Caldas-Colombia department.

NI: Not infested; TI: Total infested; TNIN: Total not infested; TM: Total of animals sampled; Pv: P value; OR: odds ratio; IC: confidence interval

Table 2 Frequency and statistical analysis of tick infestation in bovines, equines, and canines in the northern region of Caldas-Colombia department.

P: P-value; OR: odds ratio; IC: confidence interval.

Table 3 Frequency and statistical analysis of tick species found in cattle, equines and canines in the northern region of Caldas-Colombia department.

P: P-value; OR: odds ratio; IC: confidence interval.

The percentage of infestation of canines was 13 % (Table 2); the most frequent species was R. sanguineus s.l. (57.1 % of the infested animals); the presence of Amblyomma sp. in this group is highlighted, finding high statistical significance for this type of tick (Table 3).

The frequency found of Amblyomma sp. in this research is very low compared to other studies conducted in Colombia. In a survey conducted in ten Colombia departments, Rivera-Páez et al. (2018) found a high frequency of Amblyomma. Eleven percent of the ticks were infected with different species of rickettsiae; none of them corresponded to R. rickettsii (Rivera-Páez et al. 2018). In the study conducted by Faccini-Martínez et al. (2017) in the municipality of Villeta (Cundinamarca), a high frequency of different species of the genus Amblyomma was also found; 1.7 % of the ticks had rickettsiae, identifying R. rickettsii in adults of D. nitens, in nymphs and larvae of A. cajennense s.l. and Amblyomma spp. In adults of A. cajennese s.l. and R. microplus, the rickettsia species could not be identified (Faccini-Martínez et al. 2017). Several factors could explain the low frequency of Amblyomma in our study: much of the sampling was conducted at altitudes above 1,000 m a.s.l.; Amblyomma cajennense prefers lower altitudes (average 472.9 m a.s.l.), although they have been found at altitudes of 1,100 m a.s.l.; additionally, it prefers dry climates, with minimum temperatures of 20.9 °C and maximum temperatures of 31 °C and is not very resistant to sudden temperature changes (Acevedo-Gutiérrez et al. 2018); the factors mentioned above are not found in the geographic areas sampled.

The predominant tick species in this study was R. microplus. This finding is compatible with authors who state that this species is the most frequent in Colombia and Latin America, in cattle and other domestic and wild animals that are in contact with their habitats (Benavides & Romero, 2001; Estrada-Peña et al. 2006; Rodríguez-Vivas et al. 2016). Cortés Vecino et al. (2010) described R. microplus as the most frequent tick in regions such as Caldas, Antioquia and Meta and geographical areas with altitudes ranging from 2,000 to 2,903 m a.s.l. Its role in rickettsial transmission is controversial (Bermúdez et al. 2009; Oteo et al. 2014; Pesquera et al. 2015; Monje et al. 2016; Faccini-Martínez et al. 2017; Quintero V. et al. 2017); co-infestation with infected ticks or ingestion of blood from a carrier host may be factors for this tick to present in its DNA the presence of rickettsial genome (Beeler et al. 2011; Merhej et al. 2014). It has also been demonstrated in vitro that infection with R. parkeri generates a negative effect on oviposition; in addition, this tick loses the ability to transmit this rickettsia to experimental animals (Cordeiro et al. 2018). The above evidence could explain the absence of rickettsiae in this species in the present study since no multiple infestation was found in the animals studied, which is also associated with the possible harmful effect of rickettsiae on this particular species.

The percentage of infestation in the municipalities ranged from 27.5 to 69 %, with a higher frequency found in the municipality of La Merced (55 of the 80 infested animals); when analyzing the frequency of infestation against the municipalities sampled, it was found that La Merced and Neira presented high statistical significance (Table 1). In a study of the frequency of active rickettsial disease in 2012 in municipalities in the northern part of the department, it was found that of 26 people with acute febrile illness, five presented an increase of 4-fold or greater in IgG titer against R. rickettsii in the sample taken at convalescence; this finding is compatible with a rickettsial disease of the spotted fever group; the vast majority of these patients came from the municipality of Salamina (Hidalgo et al. 2013). A high proportion of ticks associated with rickettsial transmission (19 of 21 D. nitens, 12 of 13 R. sanguineus s.l., and 6 of 17 Amblyomma sp.) came from Salamina or nearby municipalities (Filadelfia, La Merced and Pácora). Amblyomma samples from the municipality of La Merced were obtained from dogs, an animal group that has more significant contact with humans. Therefore, there is a greater probability of infestation. This is evidence that these municipalities could have a higher risk of rickettsial disease; therefore, future studies could be focused on this area of the region to clarify the type or types of rickettsiae circulating not only in vectors but also in people, domestic and wild animals.

When molecular tests for the detection of the gltA gene were performed, it was found that none of the DNA samples obtained was positive for this gene; this result demonstrates the absence of rickettsial genetic material in the ticks collected. With the results obtained, it is concluded that there are ticks associated with the transmission of rickettsiae; however, for the period in which this sampling was done, the role of ticks obtained from domestic animals in the transmission of these diseases is not evident and, therefore, further studies are required to clarify how rickettsiae of the SFG group are acquired in the region.