Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

Print version ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.15 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2013

Undertaking the Act of Writing as a Situated Social Practice: Going beyond the Linguistic and the Textual*

La escritura situada como una práctica social: más allá de la lingüística y el texto

Claudia Marcela Chapetón Castro**

Professor at M.A. in Foreign Language Teaching

Universidad Pedagógica Nacional

E-mail: cchapeton@pedagogica.edu.co

Pedro Antonio Chala***

Professor at B. Ed. in the Teaching of Modern Languages

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana

E-mail: pchala@javeriana.edu.co

*This article reports findings of the research project titled: Going beyond the linguistic and the textual in argumentative essay writing: a critical approach carried out at Universidad Pedagígica Nacional in Bogotá, Colombia between August 2010 and December 2011.

**Claudia Marcela Chapetín, PhD in Applied Linguistics, is Associate professor at Universidad Pedagígica Nacional, Bogotá. She also holds an MA in Applied Linguistics degree, and a BA in English and Spanish. Her research interests include literacy practices, metaphor, and corpus linguistics.

***Pedro Antonio Chala Bejarano, M.A. in Foreign Language Teaching. He is a teacher of English at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. His professional interests include EFL literacy practices and materials design. He has authored school and university EFL teaching materials.

Received: 30-Nov-2012 / Accepted: 15-May-2013

Abstract

With an interest to go beyond an emphasis on linguistic and textual features that seem to prevail in writing practices, this qualitative action research study looked at EFL argumentative essay writing within a genre-based approach, where writing was understood as a situated social practice. A group of undergraduate students from a B.Ed. Program in Modern Languages participated in the study. Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews, questionnaires, class recordings, and students' artifacts. Findings revealed that participants undertook the writing of argumentative essays by bonding with their audience, establishing personal involvement with their texts, and giving support to their arguments. The study suggests that it is important to encourage students to focus on their sociocultural and personal context so that EFL writing can be approached in a more purposeful and meaningful way.

Key words: Writing as a situated social practice, argumentative essay writing, genre-based teaching.

Resumen

Con el interés de ir más allá de un énfasis en las características lingüísticas y textuales que parecen prevalecer en las prácticas de escritura, el presente estudio de investigación-acción cualitativa analizó la escritura de ensayos argumentativos en inglés como lengua extranjera dentro de un enfoque basado en la enseñanza de géneros, donde la escritura se entiende como práctica social situada. Un grupo de estudiantes de un programa de Licenciatura en Lenguas Modernas participó en el estudio. Los datos fueron recogidos a través de entrevistas semiestructuradas, cuestionarios, grabaciones de clase, y artefactos producidos por los estudiantes. Los resultados revelan que los participantes emprendieron la escritura de ensayos argumentativos estableciendo vínculos con su audiencia, involucrándose con sus textos, y sustentando sus argumentos. El estudio sugiere que es importante animar a los estudiantes a enfocarse en su contexto sociocultural y personal de modo que la escritura en inglés como lengua extranjera pueda abordarse de una manera más útil y significativa.

Palabras clave: Escritura como práctica social situada, escritura de ensayos argumentativos, enseñanza basada en géneros.

Résumé

Avec l'intérêt d'aller au-delà d'un 'accent mis sur les caractéristiques linguistiques et textuelles qui semblent dominer les pratiques d'écriture, cette enquête de recherche-action qualitative a fait l'analyse de l'écriture d'essais argumentatifs en Anglais comme langue étrangère, avec une approche fondé sur l'enseignement de la théorie du genre, où l'écriture est comprise comme une pratique sociale située. Un groupe d'étudiants de Licence en Langues Modernes a fait part de cette enquête. Les données ont été recueillies à travers d'entretiens semi-dirigées, des questionnaires, d'enregistrements dans la salle de classe et des écrits produits par les étudiants. Les résultats montrent que les participants ont entrepris l'écriture d'essais argumentatifs en créant des liens avec leurs lecteurs, s'engageant avec leurs textes et soutenant leurs arguments. L'enquête suggère l'importance d'encourager les étudiants à se centrer dans leur contexte socioculturel et personnel, en sorte que l'écriture en Anglais comme langue étrangère puisse être abordée d'une manière plus utile et significative.

Motsclés: l'écriture comme une pratique sociale située, l'écriture d'essais argumentatifs, l'enseignement de la théorie du genre.

Resumo

Com o interesse de ir mais além de uma ênfase nas características linguísticas e textuais que parecem prevalecer nas práticas de escritura, o presente estudo de pesquisa-ação qualitativa analisou a escritura de ensaios argumentativos em inglês como língua estrangeira dentro de um enfoque baseado no ensino de gêneros, onde a escritura se entende como prática social situada. Um grupo de estudantes de um programa de Licenciatura em Línguas Modernas participou no estudo. Os dados foram recolhidos através de entrevistas semiestruturadas, questionários, gravações de classe, e artefatos produzidos pelos estudantes. Os resultados revelam que os participantes empreenderam a escritura de ensaios argumentativos estabelecendo vínculos com a sua audiência, envolvendo-se com seus textos, e sustentando seus argumentos. O estudo sugere que é importante animar os estudantes a enfocar-se no seu contexto sociocultural e pessoal, de maneira que a escritura em inglês como língua estrangeira possa abordar-se de uma maneira mais útil e significativa.

Palavras chave: Escritura como prática social situada, escritura de ensaios argumentativos, ensino baseado em gêneros.

Introduction

Writing is an important component in many foreign language classrooms. The emergence of English as an international language has urged educational institutions to help students develop their communicative abilities instead of just focusing on the teaching of grammar. Writing, as an important language skill, has then been included in the tasks that students are supposed to develop in their English classes.

However, as Lillis (2001) states, student writing has been labelled as "problematic", with teachers arguing that students cannot write well, and texts being used as an assessment tool. Likewise, as the author points out, the essay, as a ";default genre" has been widely used in educational contexts, but little has been done to approach it as a social practice. Success in essay writing has been understood mainly from the linguistic dimension, and students have been instructed to focus their attention on how they write, taking for granted why they write, where, when, and in connection to whom. We agree with Lillis in that student writing is not a problem, but an opportunity for learning about literacy practices and how they can be approached, understood, and enhanced; working on these aspects may foster transformation in language classrooms and society.

From empiric observation and analysis of writing practices in the EFL classroom, it appeared that a descriptive and narrative approach to writing argumentative texts was privileged with little concern for social reality; besides, the students' voices seemed restricted in their discourse, as the purpose for writing was reduced to producing and submitting a product to be graded.

This study emerges as an opportunity to incorporate a new perspective towards the act of writing that could raise awareness about its dynamic nature, which is shaped by social and situated features. The main purpose of this study was to identify and describe how the students approached argumentative essay writing when it was understood as a situated social practice.

This study takes a social view of learning that acknowledges the importance of social contact for intrapersonal construction of meaning and scaffolding in learning (Bruner & Sherwood, 1975; Vygotsky, 1978). It also draws on the idea that learning is directly affected by social and contextual factors, as well as through social interactions and social relationships (Tarone, 2007). In the same line of thought, literacy is considered from a critical perspective that goes beyond the mere learning of reading and writing skills and the mastering of linguistic forms; it takes in personal, social, and cultural practices that shape the acts of reading and writing, and it provides us with tools for critical reasoning to challenge and transform sociocultural practices through reflection and careful thought (Giroux, 2001). The three theoretical considerations underpinning this study are explained as follows:

The act of writing: a socio-situated practice

Writing is described as socio-situated practice which connects language to what socially situated individuals do both at the broader level of culture and in specific situations (Lillis, 2001). This highlights the idea that writing links us to our cultural, social, situated contexts. According to Baynham (1995), writing as practice looks at the way in which writing and the writer are entrenched in institutional practices, discourses, and ideologies. In his words, to understand writing as situated social practice, it is important to consider various aspects: the subjectivity of the writer, the writing process, the purpose and audience, the text as product, the power of the written genre of which the text is an exemplar, and the source or legitimacy of that power. Baynham's proposal is central to this study, since it brings in different dimensions that challenge the perspective that writing is mainly a technical skill whose success depends on the mastering of linguistic forms and the ability of a writer to shape ideas to be decoded by the reader. To better understand this perspective towards the act of writing, we now discuss briefly the social and situated nature of this literacy practice.

Writing is social because it takes place within a social realm. It arises from the writer's need to communicate, learn, or express (Ramírez, 2007). As writers start jotting down their thoughts, they engage in dialogic communication with the world and with the powers that compel them to write. Besides, writing involves ideologies and powers that are inherently attached to the writers and that are put together in a dialogical relationship with their voice, influencing their ideas, beliefs, and feelings.

Writing as situated practice takes place at a specific moment in time and history and at a specific place in society; it makes up part of the world and acquires meaning within the context where it occurs. Two main aspects make texts situated. First, the writers' own experiences, beliefs, and feelings, which are built and shaped through contact with others; and second, those inherent to individuals such as age, gender, or race. These life experiences and personal features that students as writers bring with them are called, by Lillis (2001), voice-as-experience. These voices situate writing not only as the set of utterances that are produced in interaction, but also as cultural world views which may not be explicit in a utterance or discourse (Ramírez, 2007).

It is our belief that adopting this socio-situated perspective on the act of writing can allow students as writers to approach their situated, social, and cultural contexts and go beyond the formal and linguistic aspects implicit in this literacy practice to assume it in a more purposeful, dialogical, and meaningful way.

Argumentative essay writing

Predominantly argumentative essays deal with controversial topics; in them, an author defends a point of view that he/she considers valid (Díaz, 2002). Their main purposes include, among others, getting an adhesion, modifying a judgment, convincing, or persuading the reader to change a point of view about a subject. Argumentation, however, involves social action. That is, for persuasion to occur there needs to be a dialogic interaction between interlocutors (Ramírez, 2007) who have certain reasons and purposes to communicate and present them in order to reach an agreement.

Although establishing face-to-face interaction in a written text may not be possible in the EFL classroom, it is basic for the writer to think of the audience in order to select the ideas to be presented. Goatly (2000) describes how texts can convey and create interpersonal relationships by drawing on three dimensions: Power, contact, and emotion. Goatly also refers to various language elements that authors use in order to build up relationships with their audience: Addressing the reader directly, or expressing solidarity or separation, showing concern for the reader, reducing assertively, imitating everyday speech, or showing formality. Taking into account these aspects shows an organization of discourse in function of the readership, and their relevance at the textual level is expanded to a social level that is also implied in writing as a situated social practice.

Argumentative essay writing is understood in this study as a dynamic process of creation.1 First is the text, considered as a unit, consisting of several textual and linguistic elements; second is writing as a process of creation, thought, and use of skills; and finally is the situated social context that the writer and his/her audience belong to. We refer briefly to these three dimensions below.

With regard to argumentative essay organization, three main parts are at the core: the introductory paragraph, which presents the topic and prepares the audience favorably so that they accept the thesis; the body, which supports and develops the thesis statement and has a topic sentence (the main idea of the paragraph), supporting sentences, and sometimes a concluding sentence; and the concluding paragraph, which reminds the reader of the most important aspects and implies a reinforcement of the arguments that were used. Each of these three parts influences what can be said and done in the others, thus implying a dynamic relationship. The process of writing involves a reflective and creative author who makes decisions and becomes engaged in dynamic action with the purpose of influencing and establishing a dialogical connection with the readers. The writer, who belongs to a sociocultural reality, uses his/her personal background, knowledge, and experiences to relate to an audience and expresses his/her viewpoints with regards to issues that concern them both. To this end, the author also comes into contact with power relationships, Discourses (Gee, 2008), and social and cultural practices which make up part of his/her reality and shape him/her as a person and as a writer.

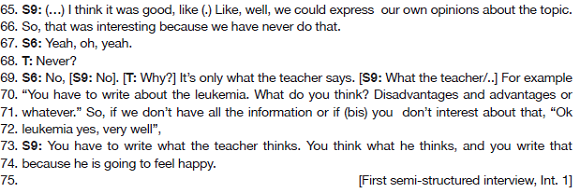

Genre as situated social action

This study draws upon the perspective of genre as social action (Hyland, 2004) and evolves to become genre as situated social action (Bastian, 2010; Miller, 1984). Thus, it goes beyond the focus on textual and linguistic aspects embedded in writing to consider the context in which texts are produced, along with the purpose of the writer, and ultimately to view writing as an attempt to interact and communicate with the audience.

Hyland (2004) states that while genres involve generalities and conventions, their understanding is more dynamic, thus favoring change and negotiation. Although linguistic and textual aspects are recognized as a part of genres, the social dimension of communication and the relationship between the genres and the social context in which they occur are more relevant. This view allows for flexibility in terms of content and form. Therefore, the approach is not limited to the repetition or copying of templates; instead, it allows students to analyze and reflect upon the organizational and linguistic features of the argumentative genre so that they can challenge the power of the text (Grundy, 1987) and take risks as to how they use rhetorical structures or frames (Hyland, 2004) and formulaic sequences (Morrison, 2010). This perspective provides opportunities to consider students' own voices and experiences, their purposes for writing, the writing processes that they follow, and the audience of their texts. This, consequently, brings into play the view of genre as situated social action.

In this respect, Bastian (2010) asserts that genres are actions occurring within specific, social, and recurrent rhetorical situations. The author states that, as social actions, genres contain ideological elements that " represent and reinforce what participants within certain rhetorical situations value, believe, and assume" (p. 31). On the other hand, Miller (1984) claims that the genre finds meaning from the social context in which that rhetorical situation arises. These visions suggest that genres are situated and acquire authentic value in the specific context in which they appear, and that in order to have a complete perspective of their meaning, it is necessary to go beyond their linguistic and textual features.

The perspective of genre as situated social action accounts for key aspects in writing. These aspects involve the writer's subjectivity to choose a topic and select the ideas that he/she wants to include in a text; the purpose and audience which account for a dialogical relationship between the writer and his/her readership; the cultural and social context in which the text appears, which imbue it with situated elements that it needs to become meaningful; and the beliefs, values, interests, Discourses (Gee, 2008), and knowledge that surround, influence, and shape the ideas that are included in the text.

Two other factors that permeate the concept of genre as situated social action in this study are collaboration and scaffolding (Bruner & Sherwood, 1975) provided by skilled writers to struggling peers (Lin et al., 2007). Appropriate scaffolding that takes place throughout the whole writing process of an essay can benefit not only how language and rhetorical structure are used in the text, but also how ideas, attitudes, and previous knowledge can be articulated with the situated context in which writing occurs, thus generating active engagement (Cotterall & Cohen, 2003).

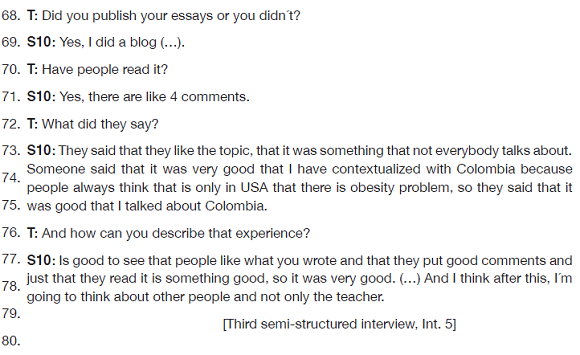

Methodology

This is a qualitative action research study that aims to generate holistic insights by looking into behavior in its natural environment (Johnson & Christensen, 2004). Action research is oriented towards educational practice, and its end is fundamentally to provide information that will contribute to the improvement of teachers' practice (Sandin, 2003). Improvement, as stated by Sagor (2000), results from the adjustments teacher-researchers can make to their action, based on the findings of their studies. This type of research allows for reflection on pedagogical practices, aiming at the generation of action towards constructive change.

Context and participants

This study was conducted at a private university in Bogotá. The participants belonged to the B. Ed. in the teaching of Modern Languages and were enrolled in the High Intermediate level of English, which is a course taken in sixth semester. A group of fifteen students (two male and thirteen female) aged 17 to 23 participated in the study. All participants signed a letter of consent indicating their acceptance to participate in this action research project.

Instruments

Four instruments were designed and used to collect data in this study. First, two questionnaires were used: one, at the initial stage of the process, to build up a participant's profile and gather data about students' attitudes towards writing; and another, applied at the end of the process, to inquire about the experience of writing argumentative essays after the intervention had taken place. Audio recordings of class sessions were used during sixteen weeks. These were highly useful, as they provided rich data on a permanent-recall basis, which included the actual words used in the interactions that took place in the development of the class activities. Artifacts (i.e. the written texts created by the participant students and the written evaluation of each cycle), collected at three different moments of the intervention, became important pieces of evidence to show the way students undertook the act of writing from a situated social perspective. Finally, three semi-structured interviews were conducted; one at the end of each cycle. Interviews became a primary data source, as they gathered students' descriptions of feelings, reactions, and perceptions of how they approached writing in the study. They also complemented and enhanced the data that was gathered through the questionnaires, the audio recordings, and the students' artifacts.

Pedagogical Design

The instructional design emerged after careful observation and reflection upon the way in which writing was being approached: mainly as an instrumental practice for students to get a grade. A second stage of the research cycle involved articulating theory (Sagor, 2005) to support the construction of the pedagogical intervention, which in turn, led to a third stage: implementing action and collecting data. This was linked to the fourth stage of the cyclical process: reflecting on the data and planning informed action.

The instructional design followed the order of topics for writing, as presented in the course program. The design was composed of three cycles, each one corresponding to a term in the semester and dealing with a different type of argumentative essay: Opinion, For and Against, and Problem-Solutions. During the implementation of the instructional design, the group of participants in the study engaged in the development of a series of activities that were designed considering writing as a situated social practice (Baynham, 1995; Gee, 2008; Lillis, 2001), and were pedagogically supported by the genre-based approach to teaching writing (Hyland, 2004; Bastian, 2010; Miller, 1984). Each writing cycle consisted of six stages: Exploring the genre, building knowledge of the field, text construction and drafting, revising and submitting a final draft, assessment and evaluation, and finally, editing and publishing.2

Findings

The processes of data analysis followed the grounded approach (Corbin & Strauss, 1990), as the aim was to gather insights from the data that had been systematically collected. This implied an inductive work, which started out with the raw data, and after a process of systematic analysis, meanings emerged.

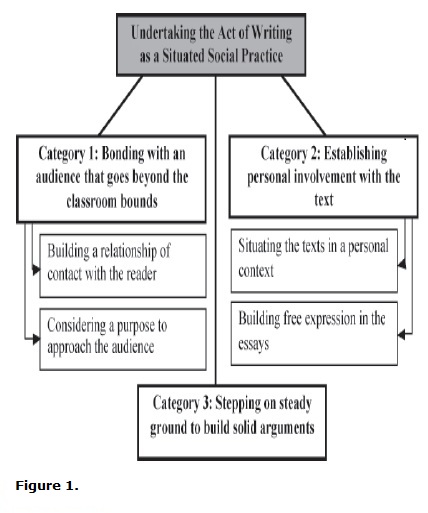

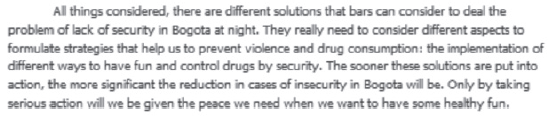

The emergent categories and sub-categories are shown in Figure 1. The data showed that undertaking the act of writing was an opportunity for participants to get involved in relevant social issues and at the same time build relationships with their audience. In so doing, they also established links between their texts and their situated context; these links were mediated by and expressed through their arguments. It was found that the bonds with the audience were built through a relationship of contact, keeping in mind the purpose participants wanted to attain. Personal involvement with the text was established by situating the text in a personal context and expressing ideas freely. When approaching the act of writing as a situated social practice, the data showed that participants also backed up their ideas with solid arguments from different sources, as well as their own knowledge of the world. Each category and sub- category is now described in detail.

Bonding with an audience that goes beyond the classroom bounds

The data showed that the participants of the study wrote their texts considering their potential readers and showing willingness to establish bonds with them. The audience that read the essays in this study involved not only the teacher but also peers and students' contacts on Facebook; this was important for the participants to go beyond the concept of audience that they had: The students had expressed in the interviews and the initial questionnaire that the audience was not an aspect to consider in their previous writing experiences, since their essays were usually read by the teacher only.

As to the bonds that were established in the essay writing experience in the study, it was clear to the students that they were supposed to have a purpose, mainly convincing, persuading, or attracting the reader. However, in their case as students of the B. Ed., the reader was by default the teacher who read and marked their papers and then gave them back with feedback and a grade; this showed a linear relationship which was mainly composed of them as authors and the teacher as the only reader. The data showed that the participants were willing to establish connections with their audience in two main ways: By building a relationship of contact and by considering the purpose of the essay.

Building a relationship of contact with the reader

The analysis of the data showed that the participants used a number of elements in their essays to establish contact with their readership. Contact is understood here as the horizontal social relationship that the author wants to establish with the reader (Goatly, 2000). The use of these elements evidenced the participants' concern not just for writing a text for the class, but also for establishing clear and close communication with their audience within a situated context.

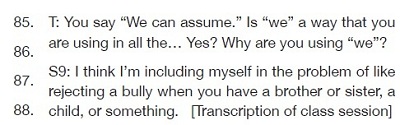

In the first place, although there were participants who preferred to use impersonal forms to express their ideas and support them, there was also an interesting tendency to use the pronoun "we" to address the readersand establish a closer relationship of solidarity, affinity, and partnership:

In Goatly's terms (2000), this was mainly an inclusive we, to include the reader in the discussion of the topic. Through the use of this pronoun, the students were able to explore a closer way to get in contact with the readership:

Writing was, as shown by the data, a way for students to involve their readers and get involved in social issues. At the same time that students wrote their texts, they participated in the ideas and Discourses (Gee, 2008) of their reality. This is directly linked to the idea of writing as a situated social practice (Baynham, 1995). Writing was more than just putting words together; it became situated social action. It involved a situated writer willing to bond with a situated audience; by doing this, they participated in the sociocultural practices that shaped them as people of the world and members of society.

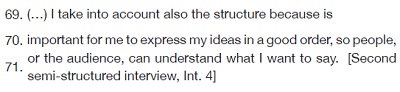

Another way for the participants to establish contact with their readership was through a careful organization of their ideas and the appropriate use of grammar and vocabulary. These aspects were revealed to have an important value, not only to shape the texts, but also to make the ideas clearer for the audience:

S1: I can support my own ideas with strong arguments, but I have to take into account grammar and vocabulary to make it easier and clearer to understand." [Final questionnaire]

The students point to the importance of organization to communicate with the audience. In this respect, Goatly (2000) suggests that the order in which we present information is crucial in organizing our material effectively. Just as the students understood the relevance of the rhetorical structure of the essays in order to meet the requirements of the genre, they also mentioned that it was important to write in a way that their ideas could be understood. There was concern for establishing a dialogic connection with the readership, and the way that ideas were presented and organized was important for communication to occur. In the students' view, formal aspects in their texts were important, but beyond this, it was implied that they wished to establish a relationship with their readers. Students expressed that they were careful to present their ideas and feelings about the topics of their essays, but at the same time it was important for them to make their texts clear, in order to connect with the audience and be able to communicate in a meaningful way.

As stated above, the writing experience in the study allowed students to build relationships not only with the teacher and their peers, but also with an external audience on Facebook or on a Blog. This was an opportunity for students to receive further ideas and comments about the essays from their contacts:

S8: "[By uploading essays on Facebook] Different people can give us their opinion about what they think about our essays and can give us feedback." [Final questionnaire]

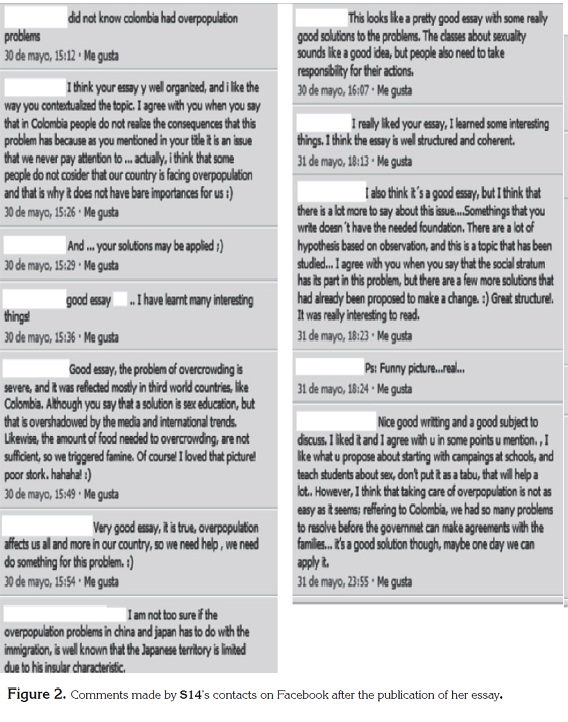

In the majority of the cases in which students published their essays, contacts cooperated to provide their points of view about the texts. Given that the essays were written in English, the audience was mainly people who could understand this language; also, depending on the topic, the number of comments varied. Figure 2 is an example of a thread of comments posted on Facebook in response to the publication of a pros and cons essay:

It is important to highlight the fact that sharing the essays generated dialogic communication (Ramírez, 2007) between the authors and their readership; the authors did not just transmit ideas to their readers but shared them instead, and this fostered dialogue.

This contributed to the building of a relationship of social contact (Goatly, 2000), which focused on the content of the texts rather than on the form, thus generating interaction. Besides, as evidenced in the comments that were generated, there seems to be an indication of a collective construction of knowledge in which different people participated with their own understanding of the issue that was being discussed. The ideas and further comments that were provided contributed to improving the participants' perception of the writing experience and acknowledging the importance of writing for an audience that was beyond the teacher and even their peers:

As can be seen here, publishing also allowed the students to focus their attention on the content of their texts and pay closer attention to how they expressed their ideas to reach the audience. Besides this, it also helped them to realize that writing does not have to be linked to the context of the classroom only, and that the audience can be different from the teacher. Although publishing the essays generated different feelings in the students, including anxiety about the readers' reactions, it was found to be a valuable and enriching experience that allowed them to share their ideas and to look at other people's points of view; that is, generating dialogic interaction with an audience that goes beyond the classroom bounds.

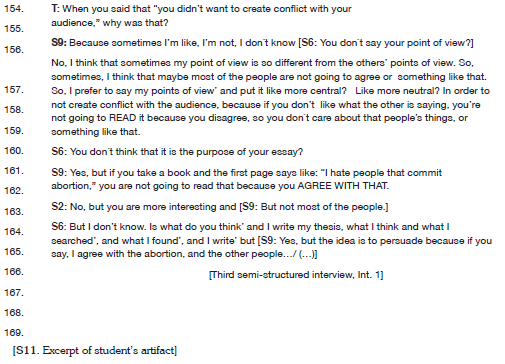

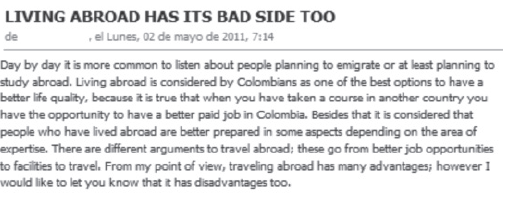

Considering a purpose to approach the audience

The data showed that identifying the purpose to write was a way to establish a dialogic connection with the reader. Students saw that through the essays they could persuade their audience to change their points of view with regards to the topics they discussed. As the essays were not read only by the teacher, the participants became more aware of the way that they were going to express their ideas and communicate with distant readers. From this perspective, then, the authors were able to articulate their discourse and the relationships that they wanted to build with their audience (Ramírez, 2007). In the following extract from an interview, a student shows how she understands the approximation she needs to make when trying to approach her audience and persuade them:

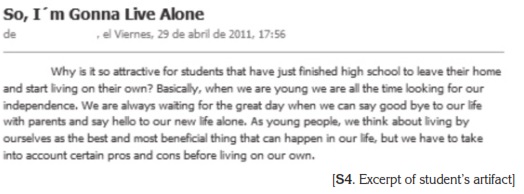

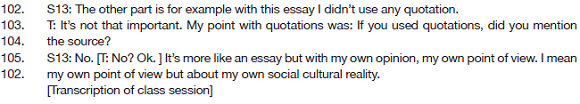

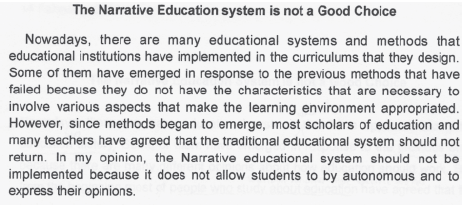

It was found that the connection that authors established with their readers was not linear; the students did not consider only their own points of view to present and convey a message, but also considered the audience's reactions and foresaw the way to reach it. The texts presented the purpose in the thesis statement, at the end of the introduction, following genre conventions, showing the students' presence, and establishing connections with the reader. The following essay introduction shows a way to express the purpose and at the same way establish communication with the audience:

In this excerpt, the writer included information of her context to introduce the topic as well as a concession idea, thus establishing two types of connection: First, she drew on knowledge of reality that her readers may share, and second, through the concession idea, she showed her consideration of points of view that were different or opposing to hers; in other words, she anticipated the audience's reactions. Besides this, she reduced her assertiveness (Goatly, 2000) when she presented her purpose, by using "From my point of view" and "I would like to." By carefully selecting forms, participants showed understanding of an interpersonal dimension of writing rather than only a linear connection between a writer and the readers. In this respect, a student wrote in the final questionnaire:

S8: "It is really important to think about the purpose of the text because it helps us to establish the way we will write and obviously we need to have good arguments that support our ideas and convince our audience." [Final questionnaire]

Through explicit analysis of the genre, socialization, and personal reflection, participants became aware that they needed to fulfill a purpose that was indeed the purpose of the genre. It was shown by the data that one way that they found to achieve their purpose was through an appropriate organization and presentation of their discourse. This would allow them to reach their audience and persuade or convince them.

Establishing Personal Involvement with the Text

The data pointed out that the participants of the study assigned an important role to getting involved with the texts when they wrote their essays. Establishing personal involvement here refers to the different ways in which the students created a link with their texts and imprinted their personal touch to make the essays theirs. Baynham (1995) states that "Not all writers are equal within the discourse community" (p. 241); this is why although explicit teaching of essay writing was provided to the whole class, it was possible for students to approach the act of writing and get involved in it from a situated and personal way. This personal involvement in the act of writing was expressed in two main ways: by situating the texts in a personal context and by building free expression in the essays.

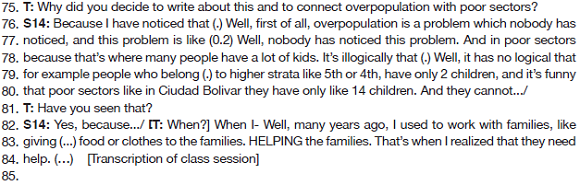

Situating the texts in a personal context

As shown in the data, the participants focused their writing experiences on their reality as students, as members of the wider society, and as people of the world. They showed involvement with the issue that they wanted to discuss, either because it was a personal experience or because in one way or another it affected them as social beings. Text situatedness allowed the participants to express their ideas in a more confident way and at the same time imbue their texts with a sense of social relevance:

[S8. Excerpt of student's artifact]

Situating the texts in their sociocultural context, as seen above, was useful for the participants to draw upon their knowledge of the world and of the reality that they were living, in order to support their ideas and connect with their readers. In other cases, personal experiences were used as the backbone to discuss a social problem; this allowed the writers to express their arguments from their own perspective:

S6: I like write this kind of essay [Problem- solutions essay] because the topic is easy and is a part of my life, so I live that problem and it is easy for me to write and to give my personal opinion." [Final questionnaire]

The students were able to build engagement with the text using an array of experiences (Lillis, 2001), which was all that they brought with them and contributed to shaping their texts. In the following excerpt of a class in which the students were presenting their final essays, a student shows how she feels connected to the topic of her essay through a personal experience, which allowed her to construct and present her own arguments:

It is important to note that by approaching writing as a situated social practice, participants were able to reflect upon their personal reality, discuss issues that belonged to their sociocultural context, and participate in the social practices that surrounded and shaped them as members of a community. Even in the first essay, in which the topic was chosen for them, the students were able to find a connection and write their ideas. This is shown by the following quote:

S7: ";My experience with this essay [Opinion essay] was really good because I liked the topic we wrote about. Although the teacher gave us the same topic I was really interested on it because I could explain my thoughts related to this subject, and because this topic is related with my major and the reality of education." [Final questionnaire]

Although being assigned a topic generated different reactions, students discussed the issue and took part in a social reality that pertained to them as students of a B. Ed. and future teachers. In this way, they were also considered as subjects that belonged to a society and participated in the social practices of an educational institution with projection to their field of work.

Building free expression in the essays

Throughout data analysis, free expression of ideas, points of view, and feelings emerged as an important way in which the participants approached the act of writing. They were able to analyze and criticize social phenomena such as educational practices, violence, or the use of technology, and suggest solutions to issues that they found problematic. Expressing their points of view was a way for them to gain control of their essays and personalize the act of writing, as illustrated in the following quote:

S3: ";My own ideas and strong arguments I think that are important because that makes my essay mine, and with that I'm able to achieve my purpose." [Final questionnaire]

The students looked for information to support and illustrate their ideas with quotations and paraphrases; however, they acknowledged the importance of presenting their own voice in the essays, and they valued the chance to express their points of view freely, without restrictions that they had previously encountered, as revealed in the collected data. The following excerpt from an interview illustrates this point:

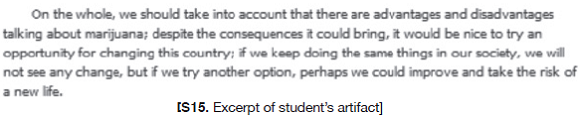

Since writing as a situated social practice involves understanding "the subjectivity of the writer and his or her implication in social practices" (Baynham, 1995, p. 208), it was important to allow students to express their opinions freely. Carte blanche given in the pros and cons essay and in the problem-solutions essay resulted in a display of students' ideas about different topics. As shown in the following pros and cons essay conclusion, participants were also careful in reducing assertiveness (Goatly, 2000), thus demonstrating awareness of the social practices and Discourses (Gee, 2008) that surround writing:

The opportunity to express their ideas was determining for participants to view writing as purposive action, rather than as an obligation in the course. It was found in the data that students' involvement when writing their essays depended greatly on their interest in and knowledge of the topic; in turn, these two factors depended on how identified the participants felt with the issue. In this respect, the data showed that even if the students did not know much about a topic, they investigated and learned about it because they found it interesting and relevant to their lives or their sociocultural context.

Stepping on Steady Ground to Build Solid Arguments

Another way in which the participants of the study approached essay writing was by supporting their ideas using different resources. This was revealed to be useful for students to build arguments with solid bases and at the same time improve their knowledge about the topics. Although the use of references was more emphasized in the second and third cycles due to reflection on the issues of quotations and fallacies, the data showed that the participants also supported their ideas with knowledge of the world and their reality throughout the whole experience:

[S8. Excerpt of student's artifact]

The data revealed that the students drew upon previous knowledge and knowledge of the world to support their points of view and express general ideas. They also resorted to specific knowledge that belonged to their personal background (Lillis, 2001) to illustrate their arguments. Likewise, voices from other sources like class or online materials that participants found authoritative were integrated and made part of their essays. This textual interaction (Goatly, 2000) was shown by the data to be a way for participants to learn about the topics and also to participate in the social practices (Baynham, 1995) and Discourses (Gee, 2008) that surrounded them. On the other hand, participants also perceived that using references in the essays was as an important element to give support and strength to their arguments and make them clear:

S12: ";As in any essay, it is imperative researching in order to support well and clarify the arguments."

[Final questionnaire]

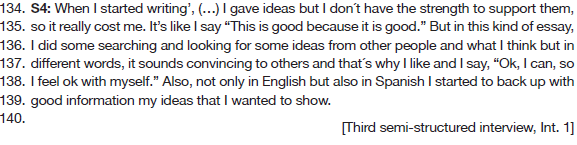

It was shown that inclusion of supporting evidence was more than just a class requirement. Other voices allowed the participants to feel more secure about their arguments, as they supported their ideas and helped them to convince or persuade readers:

Including ideas from other sources in the form of paraphrases and quotations was important for the participants to generate a more meaningful interaction with the audience and approach it with more solid arguments; they expressed ideas based not only on their perceptions of the world but also on steady ground that had already been explored by other authors.

All in all, the categories that emerged from the data analysis related in terms of the situatedness and confidence that were built through the approximation of writing as a situated social practice within a genre- based pedagogy. Participants found in this experience the opportunity to express their own ideas, and by doing this, were able to resort to their knowledge of their personal and situated context (Baynham, 1995; Lillis, 2001); besides this, they also had the opportunity to establish contact (Goatly, 2000) and dialogic communication (Ramírez, 2007) with different types of audience, which allowed them to approach writing from a more socially situated perspective, going beyond the linguistic and textual aspects.

At the same time, being immersed in a genre- based approach to writing, participants were also able to undertake this literacy practice in a more self-reliant way. They enjoyed the support of their teacher and peers through scaffolding (Bruner & Sherwood, 1975; Vygotsky, 1978), and they made an explicit discovery of key genre features (Hyland, 2004; Morrison, 2010); this facilitated the act of writing and helped them build confidence to express their arguments in the essays.

Conclusions and implications

The data showed that there were three main ways in which the participants of the study undertook writing when it was understood as a situated social practice. Firstly, the students bonded with the readership (peers, teacher and contacts on Facebook or a Blog) in two main ways. To begin with, students established a relationship of contact and dialogic communication with the audience, involving them in the essays and making their texts clear, to be understood by those who read them; in this way, meaningful communication was established. The publication of the essays on social networks was a positive experience because it fostered further dialogic communication with an external audience focusing on the content of the texts rather than on formal aspects. On the other hand, the participants also created bonds with the audience because they kept in mind the purpose of their essays; the students became aware that they could persuade or convince their readers by carefully articulating their discourse and approaching the audience through dialogic communication.

Secondly, the participants established personal involvement with the texts by imprinting their subjectivity in them. The personal involvement with the texts was expressed by situating the essays in a personal context and by building free expression in the essays. The data showed that the students were able to focus their writing experiences on their situated reality, which allowed them to draw upon their knowledge of the world and present their ideas from their personal points of view. They also analyzed issues that belonged to their context, and in this way, they participated in the social practices that surrounded them as members of society. Participants' free expression of ideas was a relevant aspect, as they could present their points of view without the restrictions that they had encountered in previous writing experiences, and because they were able to analyze different issues showing their personal voice. By expressing their feelings, points of view and ideas about social issues, they also gained control of their essays, as they could show their own voices and express what they wanted to share.

The third way in which the students undertook the act of writing was by stepping on steady ground to build solid arguments using different resources. The data showed that the participants were able to draw upon their knowledge of the world and integrate it in the essays to support their points of view; this allowed them to look at the issues from a more situated perspective. On the other hand, the data also showed that students built textual interaction by including ideas from other sources in order to back up their arguments. This connection with other texts was important in two ways: First, it helped them to learn more about the topics, and second it helped them to participate in the discourses that surrounded them as social beings. Furthermore, the data also showed that using authoritative references in their essays allowed the students to approach the audience with more solid and clear arguments, which in the end helped them to achieve their purpose too.

All in all, throughout the writing experience that was developed in this research study, the participants were able to explore different dimensions of writing, including the subjectivity that is imbued by the writers in their texts and the situated social perspective that is expressed in the dialogic communication established between the authors and their readership. Although there was still concern for linguistic and textual issues, the participants also took interest in the content of their essays; they approached writing in a different way, which allowed them to express their feelings, points of view, and ideas regarding social issues that pertained to them as members of society, and they were able to take part in the discourses and social practices that surrounded them. It was also possible to transcend the classroom practice and integrate external readers in this literacy practice, making it both purposeful and meaningful for the students.

With regards to the field of literacy, and specifically to EFL writing, this project has various implications. First, it is necessary to promote an approach in which writing is viewed as dynamic action rather than as the passive development of a skill. This action needs to involve a careful process of reflection on the part of both teachers and students, so EFL writing becomes a meaningful activity rather than an imposition. Second, it is important to view writing as situated action, closely related to the students' personal background. Approaching writing from this perspective can allow learners to express their ideas in a more self-reliant way because they can feel more confident when they write about a topic of their interest. Third, writing should be considered purposeful action; when students have a clear purpose for writing, this experience can be very fulfilling and enriching.

Notes

1See Chala and Chapetín (2012) for a detailed account of this perspective.

2See Chala (2011) for a detailed description of each one of these six stages of the writing cycle

References

Bastian, H. (2010). The genre effect: exploring the unfamiliar. Composition Studies, 38(1), 29-51. [ Links ]

Baynham, M. (1995). Literacy Practice: Investigating Literacy in Social Contexts. New York and London: Longman. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. S., & Sherwood, V. (1975). Pekaboo and the learning of rule structures. In J. S. Bruner, A. Jolly, & K. Sylva (Eds.), Play: Its role in development and evolution pp. 277-285). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Chala, P.A. (2011. Going beyond the linguistic and the textual in argumentative essay writing: A critical approach (Unpublished master s thesis). Universidad Pedagígica Nacional, Bogotá [ Links ].

Chala, P.A., & Chapetín, C.M. (2012). EFL argumentative essay writing as a situated-social practice: A review of concepts. Folios, 36, 23-36 [ Links ]

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research. Grounded theory Procedures and Techniques. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Cotterall, S., & Cohen, R. (2003). Scaffolding for second language writers: producing an academic essay. In ELT Journal, 57(2), 159-166. [ Links ]

Díaz, Á. (2002). La Argumentación Escrita. Colombia: Caminos Editorial Universidad de Antioquia. [ Links ]

Gee, J. P. (2008). Social Linguistics and Literacies. Ideology in discourses. Third Edition. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Giroux, H. A. (2001). Theory and resistance in education: Towards a pedagogy for the opposition. Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport CT, USA. [ Links ]

Goatly, A. (2000). Critical Reading and Writing. An Introductory Coursebook. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Grundy, S. (1987). Curriculum: Product or Praxis? London: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Hyland, K. (2004). Genre and Second Language Writing.Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. (2004). Educational Research. Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches. Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

Lillis, T. M. (2001). Student Writing: Access, Regulation, Desire. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Lin, S. C., Monroe, B. W., & Troia, G. (2007). Development of writing knowledge in Grades 2-8: A comparison of typically developing writers and their struggling peers. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 23, 207-230. [ Links ]

Miller, C. R. (1984). Genre as social action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70, 151-167. [ Links ]

Morrison, B. R. (2010). Developing a culturally-relevant genre-based writing course for distance learning. Language Education in Asia, 1, 171, 180. [ Links ]

Ramírez, L. A. (2007). Comunicación y Discurso. La Perspectiva Polifínica de los Discursos Literarios, Cotidianos y Científicos. Bogotá: Editorial Magisterio. [ Links ]

Sagor, R. (2000). Guiding School Improvement with Action Research. Virginia: ASCD. [ Links ]

Sagor, R. (2005). The Action Research Guidebook: A Four-Step Process for Educators and School Teams. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. [ Links ]

Tarone, E. (2007). Sociolinguistic approaches to second language acquisition research -1997-2007. The Modern Language Journal, 91, 837-848. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]