Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

versión impresa ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.15 no.1 Bogotá ene./jun. 2013

Pre-service Teachers' Construction of Meaning: An Interpretive Qualitative Study*

La construcción de significados por profesores en formación: estudio interpretativo y cualitativo

Nestor Ricardo Fajardo Mora**

Assistant Professor, School of Sciences and Education

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

E-mail: nerifamo@yahoo.es

*This article reports findings of the research project titled: The Construction of Meaning Through Text-Based Tasks: A Staring Point to Disclose Ideologies in a Group of Pre-service Social Studies Teachers carried out at Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá in Colombia between February 2009 and December 2010

**Nestor Ricardo Fajardo Mora, has a Bachelor degree in Modern Languages: Spanish-English and a Postgraduate in Language and Pedagogical Projects from Universidad Distrital. Also, he holds a Master Degree in Applied Linguistics to TEFL from the same university. He has been working in Education since 1996 in primary, secondary and university. Currently, he is an English Language Teacher in the Social Studies Undergraduate Program at UD. He is a member of "AMAUTAS" research group in areas such as Education, Critical Pedagogy, Identity, Subject Cosntruction, and Multicultural Issues.

Received: 22-Jan-2012/Accepted: 5-Feb-2013

Abstract

This research-based article presents an interpretive qualitative study with pre-service teachers of Social Studies, who construct their own meanings from social-studies texts through their roots of knowledge, their shared assumptions, and the intertextuality which are collectively related to the core category: Habitus. Using these strategies, the pre-service teachers employ their own values, understandings and representations of the world to construct meaning. The author of this research collected and analyzed the data through the methodology of Grounded Theory. Pre-service teachers' artifacts and class video recordings were used as major sources to collect data over the period of one semester.

Key Words: Construction of meaning, roots of knowledge, assumptions, intertextuality, habitus.

Resumen

Este artículo es el resultado de una investigación cualitativa interpretativa desarrollada con profesores de Ciencias Sociales en formación quienes construyen sus propios significados de textos relacionados con su campo de formación dadas sus raíces del conocimiento, sus asunciones compartidas y la intertextualidad las cuales se relacionan a su vez con la categoría Habitus que las nuclea a todas. El conocimiento previo, las asunciones y la intertextualidad de los docentes en formación les permite construir sus propios significados de los textos basados en sus valores, comprensiones y representaciones del mundo. El investigador recopiló y analizó los datos basado en la Teoría Fundamentada. Los trabajos producidos por los docentes en formación y las transcripciones de video grabaciones a lo largo de un semestre fueron los instrumentos de recolección de información.

Palabras clave: Construcción de significado, raíces del conocimiento, asunciones, intertextualidad, habitus.

Résumé

Cet article est le résultat d'une recherche qualitative interprétative développée avec des enseignants de Sciences sociales en formation, qui construisent leurs propres significations de textes en rapport avec leur domaine de formation, étant donné qu'ils partagent les mêmes racines de leur savoir, les mêmes hypothèses et l'intertextualité. Elles ont rapport avec la catégorie Habitus, qui est leur centre. Le savoir préalable, les hypothèses et l'intertextualité des enseignants en formation leur permet de construire leurs significations propres des textes fondés sur leurs valeurs, leur compréhension et leurs représentations du monde. Le chercheur a recueilli et fait l'analyse des données sur le fondement de la Grounded Theory. Les travails produits par les enseignant en formation et les transcriptions des enregistrements vidéo faits pendant un semestre ont été les instruments de recueil de l'information.

Mots clés: Construction de la signification, racines du savoir, hypothèses, intertextualité, habitus.

Resumo

Este artigo é o resultado de uma pesquisa qualitativa interpretativa desenvolvida com professores de Ciências Sociais em formação, os quais constroem seus próprios significados de textos relacionados com sua área de formação, dadas suas raízes do conhecimento, suas assunções compartilhadas e a intertextualidade, as quais se relacionam, ao mesmo tempo, com a categoria Habitus, que nucleia a todas. O conhecimento prévio, as assunções e a intertextualidade dos docentes em formação permite-lhes construir seus próprios significados dos textos baseados em seus valores, compreensões e representações do mundo. O pesquisador recopilou e analisou os dados baseado na Teoria Fundamentada. Os trabalhos produzidos pelos docentes em formação e as transcrições de vídeo gravações ao longo de um semestre foram os instrumentos de recolha de informação.

Palavras chave: Construção de significado, raízes do conhecimento, assunções, intertextualidade, habitus.

Introduction

This article describes a research study conducted with a group of pre-service Social Studies teachers, regarding how they make sense of English texts. The construction of meaning is a fundamental task for Pre-service teachers of Social Studies because, as professionals of education, they must fulfill the requests of the Ministry of Education of Colombia, defined by the National Bilingual Program. Moreover, they must be bilingual teachers and researchers in the current globalized world, who need to access a wide range of information, in order to keep up-to-date and be able to analyze social, political, economic or religious phenomena around the world. Because of this, pre-service teachers of Social Studies have to be able to construct the meaning of foreign texts; specifically English texts.

However, pre-service teachers' construction of meaning in the EFL class is a matter to be resolved, due to the lack of meaningful texts and resources implemented in English classes. Pre-service-teachers do not interact with English texts while they are reading; on the contrary, they observe reading as a tedious, meaningless, and frightening task. I consider that the use of English texts that trigger pre-service teachers' previous knowledge with EFL learning is a chance to comprehend how meaning is constructed. Consequently, the EFL class becomes a forum where social, historical, political and economic concerns can be analyzed and discussed among pre-service teachers of Social Studies, who find the opportunity to share their opinions and contrast different perspectives in the class.

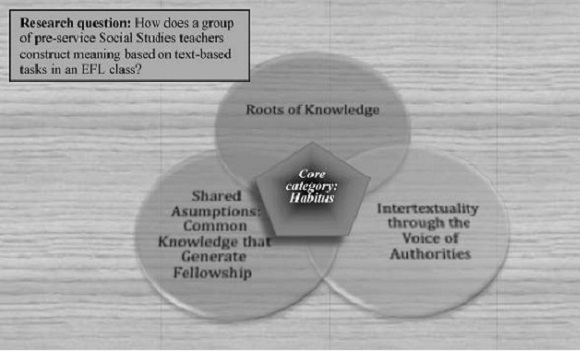

In order to account for these aspects, the research posed the following question: How does a group of pre-service Social Studies teachers construct meaning based on text-based tasks in an EFL class? Based on the research question, the objective posed was: to identify, describe, and analyze how pre-service Social Studies teachers construct meaning based on text-based tasks designed from issues pertaining to their field of study.

The results of the study give an account that Pre-service Social Studies teachers make meaning of English texts based on an internalized system of fixed and acquired dispositions, as well as on a range of personal possibilities within these dispositions that outlined schemes of perception, thought and action. That is, pre-service teachers construct the meaning of texts based on their habitus (Bourdieu, 1977). Habitus is the core category that entails three subsidiary categories: Roots of Knowledge, Assumptions: common grounds to construct meaning, and Intertextuality through the Voice of Authorities.

In this paper, I will present four main sections. Firstly, the theoretical framework that guided my study, secondly, the methodology employed in this research; following this, the findings and their discussion, and finally, pedagogical implications.

Theoretical Framework

The constructs that supported this research study are: meaning construction, construction of meaning as a sociocultural issue, and transformative pedagogy.

The Construction of Meaning

Wells (1995) points out that the process of creating meaning begins in background knowledge and its connection with new information, but this is only a first step in the whole process to the meaning itself. The next step is the immersion of this integrated information into broad cultural knowledge. From this last step, the process continues to the internalization of creating meaning.

The construction of meaning can be described through three characteristics (Wells, 1995). The first is that "[m]eanings are made, not found" (p. 237). This characteristic involves the interdependence between action and knowledge because meanings required to be actively constructed from learners' background.

The second characteristic is related to the impossibility of constructing meaning detached from learners' personal interests, cultural background, and/ or level of familiarity with the content of the subject discussed. Meaning is constructed because it has a purpose and motive which can be evaluated as valuable and value according to learners' purposes and needs.

The third characteristic of construction of meaning recognizes the transactional nature of learning and teaching. Wells (1995) emphasizes that "what we learn depends crucially on the company we keep, on what activities we engaged in together, and on how we do and talk about these activities." (p. 238). Learning cannot be analyzed aside from individual and social values that affect the construction of meaning. Wells (1995) declares "learning is as much a social as an individual endeavor and that meanings that are constructed occur, not within, but between individuals." (p.238).The previous description places emphasis on how learners construct meaning, anchored in social possibilities and constraints as well as in cultural mediations. Subsequently, I consider that construction of meaning is not a result but a process which is evolving continuously, given its permanent contact between subjects. Wells (1995) has asserted that this complete process is developed by the learner himself, guided by a more capable peer within a Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1995). As has been noted, this study has called attention to the construction of meaning as a complex process, influenced by social and personal factors. This research illustrates the relationship between the construction of meaning and a sociocultural approach, applied to foreign language classrooms.

Construction of Meaning as a Sociocultural Issue

This study recognizes that the construction of meaning is a process framed by sociocultural theory. Donato (2000) has explained three contributions of sociocultural theory to understanding the foreign language classroom. He describes the relationship between language learning and the sociocultural approach from three main viewpoints. First, from a sociocultural perspective, construction of meaning "is a semiotic process attributable to participation in socially-mediated activities." (as cited in Lantolf, 2000, p. 45). A semiotic process uses semiotic resources such as print materials, technologies, audiovisuals, physical environment or gestures, and this semiotic process places emphasis on interaction in the classroom as an unavoidable matter.

Second, Donato (2000) points out that "the negotiation of meaning in a social context is subordinated to the creation of a meaning in a collaborative act." (as cited in Lantolf, 2000 p. 46). In this way, I think that construction of meaning is not an individual and isolated task, but the result of interaction and negotiation of meanings proposed by a group of people. Interactional contexts favor construction of meaning through negotiation and these contexts change the concept of instruction for interaction where collaborative work is constantly encouraged in a foreign language classroom.

Third, the construction of meaning within sociocultural perspective recognizes the "agency" of learners (Donato, 2000), who "bring to interactions their own personal stories replete with values, assumptions, beliefs, rights, duties, and obligations." (as cited in Lantolf, 2000, p. 46). All of these pre- service teachers' agencies play an important role, given that they transform learners' realities and emerge personal agencies throughout the process of meaning construction. This situation not only empowers learners' meaning construction and sets a personal perspective, but is also the opportunity to interact with other "agencies" which can be affected and transformed mutually. In this sense, Donato (2000) asserts that "[a] central concern in sociocultural theory is that learners actively transform their world and do not merely conform to it." (as cited in Lantolf, 2000, p. 46).

As has been noted, nowadays, the issue of interaction through communication has become imp ort a n t a n d mea n in g con st ru ct ion , a s a n interactional process, enhances the possibilities of sharing information from all over the world. In the words of Roy (1990), "Language does not develop in the individual for the purpose of cognitive process but rather to facilitate social interaction." (p. 94).

In sum, I believe that construction of meaning is a sociocultural result, where semiotic processes and socially-mediated activities are involved; where negotiation between participants is crucial and learners' level agency is unavoidable. Under those circumstances, it is pertinent to set up teachers' roles and functions.From the previous approach of building meaning, the function of teachers is "more as a facilitator who coaches, mediates, and helps students develop and assess their understanding, and thereby their learning." (Lípez, 2006, p. 89). With this perspective, teachers become peers with significant experiences that can be of help for students, and significant students' experiences can be useful for classmates and the teacher himself. In this way, teachers and students are agents of change through collaborative work, where teachers do not hold the absolute truth; knowledge is constructed and validated by an interactive community. In this sense, Freire and Macedo (1987) state that "words should be laden with the meaning of the people's existential experience, and not of the teacher's experience." (p. 27). Hence, the following section articulates the pre- service teachers' experiences with the pedagogical approach known as transformative pedagogy, which creates the appropriate atmosphere to enhance the process of meaning construction carried out by pre- service Social Studies teachers.

Transformative Pedagogy: Upstream against Stupidification"

In Transformative Pedagogy, the schoo l empowers not only the students but also the teachers. A Transformative Pedagogy reflects upon the real state of order from a critical perspective that provides a deep analysis into the fossilized positivism that for many years claimed an asocial analysis of things, facts, and ideas. Giroux (2003) argues how these positivist ideas had "subordinated human consciousness and action to the imperatives of universal laws." (p. 28).

The nature of education began to develop a critical theory of social education through analysis of culture, mass media, ideology, power and authoritarianism, as instruments of the imperative rationality. In this sense, the nature and purposes of education are starting an upstream that unmasks current mainstream canons that search for a society in which justice succeeds, despite real conditions of injustice. As a result of this counter-hegemonic education, the work of teachers cannot be limited to the "stupidification" (Macedo, 1994) of the education in which "students have learned to respond to the expectations of the teacher: parroting, memorizing, and regurgitating from a series of facts and official bodies of knowledge promoted by the mainstream canon." (as cited in Bahruth & Steiner, 2000, p. 119).

Teachers' mission is the other way around, to wit: to empower their learners' learning processes; thus, learners will be able to analyze the status quo of reality. Learners inquire into the world around them, but also they need reflect upon themselves. The way to implement this Transformative Pedagogy with my pre- service Social Studies teachers is through the inclusion of appealing topics related to their interests, through which they can express their own meanings and put into context key concerns that apply to everyone.

Methodology

This interpretive qualitative research study (Merriam, 2002) takes place at a public university in Bogotá, with pre-service Social Studies teachers who belong to an undergraduate program called Licenciatura en Educación (Bachelor in Education). It aims to respond to the research question: How does a group of pre-service Social Studies teachers construct meaning based on text-based tasks in an EFL class?

The participants are 26 pre-service Social Studies teachers; 8 females and 18 males, whose ages range from eighteen to thirty-four years old. Most of them are in seventh semester of their program, in the course "Foreign Language Text Comprehension. This course meets for two, 100-minute sessions per week.

The task-based learning approach (Ellis 2006; Murphy, 2003; W illis, 1996; and W ink, 2005) framed the instructional design. It is an approach through which transformative pedagogy can make concrete and fill the gap between experiences, theory, and practice, as pre-service teachers have an unconventional path to construct the meaning of audio, video and/or iconic texts (Willis, 1996), which are pertinent to their field of professional formation.Throughout the semester, the participants and I were involved in an intervention plan divided into two periods: The first was the starting point: Historical background; the second, contemporary issues. A variety of tasks were developed during these two moments: participants listed, ordered and sorted information, and shared their personal experiences around a topic, explaining their perspectives orally or in writing, and comparing and solving problems. Among the dynamics of the interaction, it is important to mention pair work, small group discussion, socialization and plenary.

Data Sources

According to the type of research, the questions and characteristics of the research experience, I, as researcher, selected two instruments for data collection: first, video recordings (Burns, 2001) and second, students' artifacts (Lankshear & Knobel, 2004), such as personal written exercises, oral discussions, written guides, or video clips. These instruments helped to discover how the construction of meaning takes place. Grounded Theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) fits with the purpose of my research because this inductive theory of analyzing data allowed me to describe and explain systematically the process of construction of meaning ("the how").

Data Analysis

The data was analyzed within the framework of Grounded Theory Approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). This is a data analysis method in which the theory is built from the data. It is an inductive approach that moves from general and apparently disorganized data to a specific theory that explains a phenomenon. Freeman (1998) argues that "in a grounded analysis you are uncovering what may be in the data." (p. 103).

Findings

The data analysis process led me to identify one core category and three subsidiary categories that answer the research question: How does a group of pre-service Social Studies teachers construct meaning based on text-based tasks in an EFL class? As stated by Strauss and Corbin (1990), a core (or nucleus) category must be the sun standing in orderly systematic relationship to its planet. Although each subsidiary category stands alone, they collectively relate to the core category and also have a relationship among themselves. I called the core category that emerged from the analysis of the data: Habitus (Bourdieu, 1977) and this will be explained in detail after the analysis of three subsidiary categories identified.

With this in mind, I can state that pre-service Social Studies teachers construct meaning from texts based on their habitus. In other words, pre-service teachers construct the meaning of texts based on that internalized system of fixed and acquired dispositions as well as on a range of personal possibilities within these dispositions that outline schemes of perception, thought and action. From this core category, came three subsidiary categories in relation to my research question. In the following diagram, the relation between subsidiary categories and the core category is presented, before a discussion regarding each one individually

Roots of Knowledge

Pre-service Social Studies teachers construct the meaning of texts "looking closely" (Whitin & Whitin, 1997) because they dig for reasons to explain what or where the origins of phenomena are. Hence, they observe phenomena closely, with the intention of building suitable explanations that can set up a bench line. "Looking closely is to be aware of the limits of one's vision, acknowledging what is not seen, grappling with the problems of scientists." (p.26). Pre-service teachers express their own opinions and expectations about a topic using categories taken from Social Studies, where values, ideals, and/ or feelings that are deeply rooted in teachers' own previous experiences emerge. The human condition, social interaction, economic and political tensions are called into question by pre-service teachers who are continuously looking for new trends and opportunities for comprehension. Finally, they look closely because they confront their perspectives with those that the writer expresses in a text. Below are some excerpts that illustrate how pre-service teachers construct the meaning of texts by looking closely. The following sample demonstrates Giga's former opinion of the contents of three photographs presented in a brainstorming exercise where the question asked was: What do you imagine they are doing?- They are listening some kind of instruction to start a mechanical work, I say that because they are making a line, they look like domesticated animals they are uniformated

- He looks like an entity, he has a uniform, and he hasn't any expresion in his face, he is completely absorbed by the system.

- Fidel is giving a speech, a reactionary speech." ([sic]GigaTsk5Q2)

These comments reveal Giga's perception towards the labor field where those who "listen instructions" [sic] and follow them are doing "mechanical work" [sic] like "domesticated animals" [sic]. She feels negative about a field of work where people have to accomplish specific tasks in a group. She is consistent in her second comment, where she observes an "entity" instead of man just because "he hasn't any expresion [sic] in his face, he is completely absorbed by the system." Throughout her three comments, there is a constant use of social categories like "mechanical work", "the system" and " reactionary speech". Moreover, Giga's comments inquire about current human conditions in a labor field, where human conditions, social interactions, and economic tensions demand to be understood from new trends.

The pre-service teacher identified as Natbej expresses her opinions in favor of and against the role of the technology in current life. This construction of meaning through looking closely is based on the reception of the text and how it is understood by the reader.I agree with John Zerzan when he said that modern technology favors distancing over closeness because the main objective is that people can communicate at a distance but I don't agree [with him] in thesecond part of the argument because the technology is a way of playing for people and efficiency is necessary for capitalistic functions. (NatbejTsk5.1Shapex)

Finally, Natmon is constructing meaning because she is looking closely and confronting the arguments presented in a text that explains socio-historical issues that could be considered during the emerging of North American expansionism at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth.

I think that the text uses a quite weak argument to justify the economic disadvantage promoted by United States in regard to other countries [based on] the incoherent argument of Darwin's evolution. (Tsk2NatmonShapex)

This text focuses on how Charles Darwin's theory of Natural Selection was used as the most relevant issue to explain the phenomenon of the imperialism of The United States. She looked closely at the reading and realized that "the text uses a quiet weak argument"; therefore, Natmon detects the limitations the text has in terms of arguments and acknowledges how this is an "incoherent argument". I can infer that she is considering other arguments that are not evident; however, she portrays her viewpoint against the perspective of North American imperialism supported merely by Darwin's theory of "survival of the fittest". The economical advantages of the United States justified by Social Darwinism are not enough for Natmon.

To summarize, Roots of Knowledge is the first category that emerges when pre-service teachers are constructing meaning of texts. This category is characterized by looking closely and digging deep into a phenomenon. To be precise, pre-service teachers carry out in-depth reflection with the purpose of having a complete panorama of a specific issue. They confront their perspectives with those that the writer expresses in her/his text. Former opinions from the academic background are part of looking closely because they allow them to encompass opinions which include the use of concepts borrowed from Social Studies and personal perspectives.

The second category that emerges when pre- service teachers are constructing meaning of texts is based on the common grounds that they share. This category is called Shared Assumptions: Common Knowledge that Generates Fellowship.

Shared Assumptions: Common Knowledge that Generates Fellowship

Pre-service Social Studies teachers' excerpts revealed how they are linked by some common grounds. Those "common grounds" (Fairclough, 2003, p. 55) between participants allow the building of a common platform from which it is easier to interpret feelings of fellowship and enhance meaning construction among them. Pre-service teachers inquired about the phenomenon of consumerism in our current society, to wit:

How the consumer society changes the image of the people and the society itself. [It is a society in] which discrimination is a constant because you are important [if] you can consume more. (Tsk5HuyegarPrtsk).

This sample shows that Huyegar considers ";discrimination" to be one effect of consumerism ";because you are important [if] you can consume more". He establishes a causal relation between the level of consumerism and the level of acceptance or rejection. Due to the fact that a discriminatory attitude towards someone is nowadays considered against one's human rights, the interdependence level between acceptance and discrimination, given the consumption level, is not seen as a desirable attitude.

The implicit meaning of a text has considerable importance in society because all forms of association and solidarity rely on meanings shared by a group or community. Pre-service Social Studies teachers construct the meaning of texts having in mind some "common grounds" that are shared and sometimes taken for granted by the majority of them.

The sample taken from this pre-service teacher shows how his construction of meaning is framed by common regulations that are in harmony with "common grounds" (Fairclough, 2003). Those regulations have been socially and politically inherited by a Social Studies pre-service teacher, who, as a social agent of change, is objective in his/her aspirations and the social requirements. Therefore, the assumptions built in this case are in a close relationship with the habitus proposed by Bourdieu (1977). These hidden assumptions belong to particular projections of the society about the role that a teacher should play in it. In this case, social dispositions or habitus determine pre-service teachers' decisions.

This 'common ground' (Fairclough, 2003) creates common meanings, which are shared by them and make a stronger sense of community, as well as enhanced meaning construction. These implicit agreements and social communication are what Bourdieu (1977) calls habitus. As we can see, the core category habitus is present throughout this typology of assumptions. The reader will find a deeper analysis of the habitus core category in the last section of these findings.So far, I have presented the first two subsidiary categories: Roots of Knowledge and Shared assumptions: common knowledge that generates fellowship, which enlightens how construction of meaning is developed. The third subsidiary category that attempts to explain the process of construction of meaning is what I have named Intertextuality through the Voice of Authorities.

Intertextuality through the Voice of Authorities

According to Fairclough (2003), "the Intertextuality of a text is the presence within it of elements of other texts which may be related in various ways" (p. 218). Pre-service Social Studies teachers include several arguments from different sources with the purpose of explaining their ideas. Identifying which voices are included is a complex task. However Fairclough (2003) proposes a broad question that will be analytically useful to begin with the analysis. That question is: "Which texts and voices are included, which are excluded, and what significant absences are there?" (p. 47).

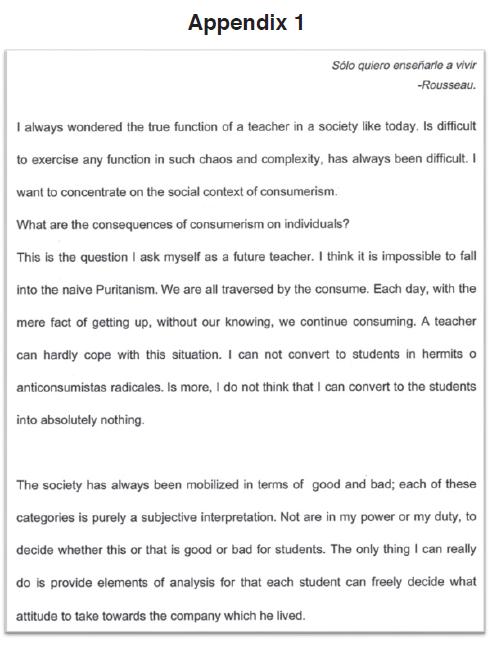

The following excerpt will be helpful in the process of answering that question (to read the complete sample, see Appendix 1). Which voices are included? A pre-service teacher, identified as Wilpri, employs Rousseau's voice as the epigraph of his written reflection. He writes:"Sólo quiero enseñarle a vivir -Rousseau." ([sic]Tsk5.1WilpriTt&Consumerism)

(Life is the trade I would teach him-Rousseau.)

Wilpri includes Rousseau's voice as an attributed voice that defines the tone of his reflection. Moreover, this attributed voice is used as a voice of authority that belongs to the prestige of Jean-Jacques Rousseau as an educator. This epigraph belongs to the treatise of the nature of education, also well-known as Émile: or, On Education. It also helps the reader to be alert to the content and how pertinent it is to the whole text, as it is directly linked to the ideas expressed throughout. For example, the first paragraph says:

I have always wondered what the true function of a teacher is in a society like today's [It] is difficult to exercise any function in such chaos and complexity. (Tsk5.1WilpriTt&Consumerism)

These comments include an evaluation of current society, where teachers find it "difficult to exercise any function" because society is characterized by "chaos and complexity". Moreover, he includes two categories which divide society in terms of "good" and "bad". He writes:

The society has always been mobilized in terms of good and bad; each of these categories is purely a subjective interpretation. It is not under my control or not my duty to decide w h e t h e r this or that is good or bad for students. (Tsk5.1WilpriTt&Consumerism)

Which voices are excluded from Wilpri's reflection? He excludes voices that consider education, the school system, and the teacher as some of the most important cornerstones in the development of a society. He pretends to be that teacher explained by J.J. Rousseau who does not point out to his students what is good or bad because he does not attempt to affect or shape his pupils' character. If we consider the epigraph, participant Wilpri attempts only to be the teacher who gives his pupils an idea about life but his pupils are who decide what, when, and how to perform.

Undoubtedly, Wilpri maintained a coherent posture throughout his reflection. His point of view reflects the relationship between the subjects and society, particularly the tension between the innate human goodness and the corrupt society. Finally, the voices he included complement each other, making the written exercise consistent with a perspective on education.

In contrast, there is another pre-service teacher who included voices that were excluded in Wilpri's reflection. She used voices that perceive the school and teachers as crucial social actors (to read the complete sample see Appendix 2). She wrote:

If we [as teachers] do not educate the child today, it will be totally absurd to try to correct the man of tomorrow. Thus, it is vital that we educate for the preservation of life and not for its destruction. (Tsk5.1GigaTt&Consumerism)

The participant Giga recalls Pythagoras' maxim when he states "Educate the child and there is no need to punish the man". The learner included Pythagoras' maxim in her reflection without any introduction as Wilpri did. Fairclough (2003) explained that those are voices related in different ways. Wilpri reports Rousseau's voice directly, using an epigraph, while Giga reported Pythagoras' aphorism indirectly.

To sum up, these two pre-service teachers constructed their discourses or meanings from different perspectives, but both framed and shaped their reflections with elements from other texts. The Intertextuality through the Voice of Authorities emerged as the third subsidiary category that explains the process of construction of meaning.

After the previous discussion that asserts the three subsidiary categories explaining the main question about how pre-service Social Studies teachers construct the meaning of text, I will proceed to present the core category: habitus.Habitus: Core of Meaning Construction

The core category that explains how pre-service Social Studies teachers construct the meaning of the text is habitus (Bourdieu, 1977). In this research study, we will find the core category habitus throughout the instruments used to collect the data (students' artifacts and class video recordings). At this point, it is important to remember that students' artifacts and class video recordings were the result of the instructional process whereby they analyzed and discussed issues related to the field of Social Studies. For example, pre-service teachers analyzed political, economical, social and religious aspects that encompassed the embracing of Charles Darwin's theory of the origin of species by politicians and expansionists in The United States. Pre- service teachers also discussed issues such as yellow journalism in close connection with the responsibilities of the press when reporting stories and the current economical model framed by consumerism, among other issues.

The habitus revealed by this group of students towards the application of Darwin's theory to the expansion of the U.S. during the last part of the XIX century and the beginning of the XX, is exemplified as follows:

People often interpret social and political theories according to their convenience because in the field of Social Studies theories are submitted for different interpretations; nothing is fully established in the field of Social Studies. In that sense, the theories are often misunderstood. For example, Bolivar's ideas are not the same for President Uribe as they are for President Chávez. (Tsk2MigonzProsolvi)

The participant identified as Migonz expressed in his problem-solving task that individuals have the right to interpret a theory without restraints. Therefore, a theory can be interpreted in different ways with the purpose of benefiting from it. Pre-service teachers also discussed this overlapped theory in an oral debate which was video recorded. The teachers also showed their habitus.

"OK, this is the idea. We consider Darwin's theory to be too broad. It permits a wide interpretation concerning whatever the perspective is and it is appropriate to cases at hand... whether conquest, power or expansionism cases. The theory of natural selection is applicable to all of these." ([sic]VR1L102-105Yesgam, p. 4)

Habitus allows them to categorize as adequate, worthy and right to make use of a theory. Right and wrong parameters in the use of theory are defined as how useful a theoretical framework is, vis-a-vis personal needs.

Previous excerpts claim the use of theory with the purpose of legitimizing and protecting someone's own arguments where personal interests are privileged. These students coincided on the "convenience" pattern in the adaption of knowledge. All of them argue in favor of accommodation of the theory to personal interest, taking into account personal conveniences and intentions.

Most students reveal their ingrained perceptions, or habitus, towards the role of the newspaper and its responsibility when publishing news. The following excerpts exemplify a generalized perception:The press has the responsibility of offering reliable and true information; it is an ethical duty." ([sic]Tsk3StvperCreActPh)

In this sense, another student claimed the following:

"I think that the press is a means of information. The reporter would be limited to informing the public and be responsible for interpretations of reality. The press is responsible for what happens after publishing news." ([sic] Tsk3NatMonCreActPh)

Both students' excerpts emphasize the role of newspapers in terms of duties, reliability, and truthfulness as a call for ethical practices. Habitus as the core category opens up possibilities for explaining how pre-service teachers can build a practical scheme of perception and appreciation that will permit them to classify as adequate or inadequate, worthy and unworthy and evaluate parameters about right or wrong, as we have seen in previous samples.

The core category habitus is built on these three subsidiary categories: Roots of Knowledge, Shared Assumptions, and Intertextuality through the Voice of Authorities. Throughout the identification of those subsidiary categories, the core category habitus will be present.Discussion of Findings

The analysis demonstrated that Pre-service Social Studies teachers made meaning of texts based on their habitus. In other words, pre-service teachers constructed the meaning of texts based on that internalized system of fixed and acquired dispositions as well as on a range of personal possibilities within these dispositions that outlined schemes of perception, thought and action Students' personal experiences were developed from the inculcation of social structures into their subjectivity. Thus, pre- service teachers integrated not only their previous knowledge, assumptions and intertextuality, but also their ideologies that would emerge toward those lasting and transferable dispositions, better known as the core category, habitus.

The first subsidiary category, identified as Roots of Knowledge, explains how participants construct meaning from their theory of the world. The second subsidiary category, Assumptions: common grounds to construct meaning, clarifies how pre-service Social Studies teachers shared socially constructed meanings, or assumptions. These common grounds were crucial, given that they generated a feeling of fellowship and acceptance among a wider network or community. The third subsidiary category, Intertextuality through the Voice of Authorities, proposes the inclusion of arguments from other voices as a way to make meaning from texts pertaining to their field of study. The inclusion of attributed quotes or voices from social-studies texts was made by participants with the intention to give relevance to their discourse and make it stronger and more valid.

The construction of meaning was also carried out thanks to the active involvement of students. Participants in this study had the opportunity to interact with texts related to social, historical, and economic aspects, where they could contrast and enrich their own vision of the world through the knowledge of others' vision. Taking into account pre- service teachers' needs, background, and interests, they are encouraged to participate effectively in the classroom, by being given a voice and an active role in their process of EFL learning.

Tasks based on texts are an option to be implemented in those settings where EFL learning is characterized by rejection, boredom, or lack of interest. To create a community of inquirers within the English language classroom would engage those learners who find neither a professional nor a personal option in EFL learning. As a consequence, during this research experience, English classes became the space where students could share reactions provoked by readings. This experience gave the chance for groups to speak, reflect, and interact in the English language.

The class environment generated by the implementation of tasks based on texts allows students to speak and participate in a relaxing context where social, political, economical, ethical, and epistemological issues emerged through individual work, small group work, and debates. Reading is perceived as a constructive and meaningful practice, when learners connect their own experience with a text and can make sense of it, and they found reading practice attractive to their interests. In this sense, texts pertaining to pre-service Social Studies teachers provoked spontaneous responses from them and at the same time gave them confidence in their English learning process.

Finally, construction of meaning is more than a pedagogical task for teacher as researcher; it is a social, professional, and personal commitment. Following Freire (1970, 1993) and Dei, (1996) "If youth come to the classroom as embodied subjectivities that are embedded in history and memory, should we as teachers not couple their word with their world?" (as cited in Ibrahim, 1999, p. 365).

Pedagogical Implications

Research studies based on meaning construction give teachers access to students' tool kit of knowledge, as they discover their ingrained strategies used during the English learning process. As a result, the classroom context becomes a place where not only previous EFL experiences, background, agreements and disagreements emerge, but also students' subjectivities as approval, rejection, fear, confidence, anxiety, and/or assurance. For an inquisitive teacher to understand previous classroom context is valuable and indeed vital.

In this sense, I consider that teachers in the EFL setting must provide opportunities for interaction in the classroom. Throughout this research study, pre- service Social Studies teachers were provided with opportunities to face a challenge; they were then engaged in EFL learning. Students felt satisfied when they could speak, write, listen, and read in English. The classroom interaction generated when they shared their own reflections increased their confidence, as they made their capacities to interact comprehensively evident. As a result, there was an improvement in their self-esteem as English learners.

During this research study, English class was a means to enhance students' sensitivity towards their own way of constructing meaning of texts, as well as to understand their own ideas and values towards EFL. The students expressed the importance to develop English communicative competencies and some realized their shift in perception toward English. EFL teachers need to unveil their students' assumptions toward English and its learning, and should design tasks according to the characteristics of their learners.

Finally, I propose some questions that can be considered by any teacher-researcher interested in exploring his/her own context of practice: What are the characteristics of an EFL setting where students and teachers can be genuinely engaged? What teaching strategies should be implemented when content areas are being dealt with in an EFL class? How can an inquiry-oriented approach be implemented with pre-service teachers? What arguments do students construct when they interact with texts? What subjectivities emerge in EFL learning? What is the relationship between EFL learning and teacher development as a transformative intellectual? How can EFL learning promote reflection on teachers' roles in Colombian society in a group of pre-service teachers?

References

Bahruth R., & Steiner, S., (2000). Upstream in the mainstream. Pedagogy against the current. In . F. Steiner, H. M. Krank, P. McLaren, and R. E. Bahruth (Eds.), Freirean Pedagogy, Praxis and Possibilities: Projects for the New Millennium. (pp. 119-145). Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Burns, A. (2001). Collaborative Action Research for English language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University press. [ Links ]

Ellis, R. (2006). The Methodology of Task-Based Teaching. Retrieved March 25, 2008 from http://www.asian-efl-journal.com/September2006EBook_editions.pdf Wesley Longman.Fairclough, N. (2003). Analyzing Discourse. Textual Analysis for Social Research. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Freeman, D. (1988). Doing Teacher Research: From Inquiry to Understanding. Canada: Heinle and Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Freire, P. and Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the Word and the World. Westport, CO., Bergin & Garvey [ Links ]

Giroux, H. (2003). Critical Theory and Educational Practice. In: A. Darder, M. Baltodano and R. Torres.The Critical Reader (pp.27-56). New York: Routledge Falmer. [ Links ]

Ibrahim, A. (1999). Becoming Black: Rap and Hip-hop, Race, Gender, Identity. and the Politics o f E S L Learning. TESOL Quarterly. Vol. 33 (3), 349-367. [ Links ]

Lankshear, C., and Knobel, M. (2004). A Handbook for Teacher Research: From Design to Implementation. New York: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Lantolf, J. (2000). Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lípez, M. (2006). Exploring students EFL writing through hypertext design. CALJ, (8), 74-122. [ Links ]

Merriam, and Associates. (2002). Qualitative Research in Practice: Examples for Discussion and Analysis. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [ Links ]

Murphy J. (2003). Task-based learning: the interaction between tasks and learners. ELT Journal, 54 (4), 352-359. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Roy, A. (1990). Developing second language literacy: A Vygotskyan perspective. Journal of Teaching Writing. 91-98. [ Links ]

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Wells, G. (1995). Language and the inquiry-oriented curriculum. Curriculum inquiry. Cambridge and Oxford: Backwell Publishers. In: Garzín, N. (2006). The electronic text and a new nature of literacy. CALJ, (8), 203-215. [ Links ]

Whitin P, and Whitin, D. (1997). Inquiry at the Window. Pursuing the Wonders of Learners. Ports - mouth: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Willis, J. (1996). A Framework for Task-Based Learning. Edinburgh: Addison Wesley Longman Limited. [ Links ]

Wink, J. (2005). Critical Pedagogy. Notes from the Real World. New York: Addison Wesley Longman. [ Links ]