Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

Print version ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.15 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2013

Writing skill enhancement when creating narrative texts through the use of collaborative writing and the Storybird Web 2.0 tool*

Mejoras en las habilidades escriturales a través del uso de escritura colaborativa y de Storybird 2.0 al crear textos narrativos

Yeison Edgardo Herrera Ramírez**

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

hawkdufolk@yahoo.com

*This article is a result of the M. A. research project, "Metacognitive awaress and enhanced autonomy through the use of collaborative writing and "storybird."

**Yeison Edgardo Herrera Ramírez has been a full time English language teacher working for Universidad Distrital for over 8 years. He holds a Master in English Language Teaching – Autonomous Learning Environments – from Universidad de la Sabana and an ICELT diploma granted by the University of Cambridge. Over the last five years he has trained learners and government teachers willing to take international exams administered by the British Council. His main research interests center on the areas of ICT, blended and virtual learning, metacognitive strategies and autonomy, semantics and pragmatics, as well as on, functionalist, cognitivist and/or constructionist approaches.

Received: 30-Apr-2013/Accepted: -Nov-2013

Abstract

The purpose of this article is presenting how the use of Collaborative Writing (CW) through Storybird, a web 2.0 tool which promotes the creation of stories collaboratively, led two groups of learners to improve certain specific aspects of their writing skill. Both groups, the former one with fifteen students and the latter one with ten students, were about to complete a two-year general English course at Instituto de Lenguas de la Universidad Distrital (ILUD) in Bogotá, Colombia. Although their English language proficiency was expected to be at an upper-intermediate level (B2) according to the Common European Framework of Reference for languages (CEFR), their writing skill was below average. Two pedagogical interventions were performed at two diferent times, the first one from October to November 2010, and the second one from March to April 2011. Pre and posttests, focus groups, surveys and reflective journals were used and data was analyzed following coding procedures. The findings revealed that the CW supported with Storybird encouraged learners to create narrative texts and their positive attitude towards the production of stories increased. Moreover, an improvement in learners' vocabulary and increased attempts to use complex language forms to write were noticeable.

Key words: CALL, Collaborative writing (CW), Web 2.0, Storybird.

Resumen

El propósito de este artículo es presentar cómo el uso de la escritura colaborativa a través de Storybird, una herramienta web que promueve la creación de historias en equipo, llevó a dos grupos de estudiantes a mejorar aspectos específicos en su habilidad para escribir. Ambos grupos, el primero de quince estudiantes y el segundo de diez, se encontraban a punto de finalizar un curso de inglés general de dos años en el Instituto de Lenguas de la Universidad Distrital (ILUD) en Bogotá, Colombia. Aunque su nivel de suficiencia en el idioma inglés se esperaba que fuera de nivel intermedio alto (B2) de acuerdo al Marco Común Europeo de Referencia para lenguas, su habilidad para escribir se encontraba por debajo del promedio. Se realizaron dos intervenciones pedagógicas en dos periodos de tiempo diferentes, el primero de octubre a noviembre de 2010, y el segundo de marzo a abril de 2011. Los datos se recolectaron en pre y pos-tests, grupos focales, encuestas y diarios de reflexión, y luego se triangularon siguiendo procedimientos de codificación. Los resultados revelaron que la escritura colaborativa apoyada con Storybird motivó a los estudiantes a crear textos narrativos y su actitud positiva hacia la producción de historias aumentó. Por otra parte, se notó una mejora en el vocabulario de los estudiantes y sus intentos para utilizar formas de lengua más complejas aumentaron.

Palabras clave: CALL, escritura colaborativa, Web 2.0, Storybird.

Résumé

L'intention de cet article est de présenter comme l'utilisation de l'écriture collaborative à travers de "Storybird", un outil Web qui promeut la création d'histories en équipe, a apporté à deux. Les deux groupes, le premier avec quinze étudiants et le deuxième avec dix étudiants, étaient sur le point de finir un cours d'anglais général de deux ans dans l'ILUD (Instituto de Lenguas de la Universidad Distrital) à Bogotá, en Colombie. Bien que leur niveau d›anglais devait être intermédiaire supérieur (B2) selon le Cadre Européen commun de référence pour les langues, leur compétences en écriture était inférieures à la moyenne. On a fait deux interventions pédagogiques dans deux périodes de temps différentes, la première d'Octobre à Novembre 2010 et la deuxième de Mars à Avril 2011. Les donnés ont été recueillies en épreuves réalises avant et après, dans des groupes de discussion, enquêtes et journaux de réflexion, après on a triangulé en suivant des méthodes de codage. Les résultats ont révélé que l'écriture collaborative soutenue avec Storybird a motivé aux étudiants à créer des textes narratifs. D'autre part, on a remarqué des progrès dans le vocabulaire des étudiants et de leurs tentatives d'utiliser des formes linguistiques plus complexes qui ont augmenté aussi. Les étudiants ont été encourages à écrire des textes plus narratifs et leur attitude positive vers la production d'histories a grandi notablement.

Mots clés: Écriture collaborative, CALL, Web 2.0, Storybird.

Introduction

Colombia is a country where the policies and regulations concerning bilingualism are promulgated by the national government in the National Bilingualism Program 2004 -2019 (NBP) which includes the communicative competence standards required to be a competent user of English as a foreign language (MEN, 2005). Respectively, the standards outlined in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) were delineated as the norm that ruled institutions and language schools to define their syllabuses and programs.

Nowadays, higher education institutions and universities offer general and academic English programs that take learners to achieve upperintermediate (B2) or Advanced (C1) levels of English language proficiency. ILUD supports and trains people interested in improving their English language and reach an upper-intermediate (B2) level of proficiency. Learners from diverse universities, schools, public workers and any person interested in learning or improving their English language proficiency enroll the general English courses. When learners culminate the general English Language program, they take the FCE1 exam administered by the British Council. After analyzing the results that various groups of learners had from 2007 to 2009, their performance showed that the lowest marks were presented in the second part of their writing papers when they wrote stories.

Bearing in mind the limitatons learners had when doing their writing tasks, it was necessary to look a different strategy to help learners to improve the writing skill. This study highlights emerging features when two groups of learners being trained to take the FCE exam, volunteered to attend sessions to reinforce their narrative writing skills. The pedagogical treatment was focused on the creation of stories using the CW as a strategy to learn to write and the use of Storybird, a web 2.0 tool designed to promote CW in and/or out of the classroom.

The use of Storybird to support the creation of narrative texts when working collaboratively, shows how the use of new technologies might help teachers to deal with academic matters and learning challenges in the 21st century school. The use of the internet, social networks, virtual platforms and web 2.0 tools to reinforce, consolidate and/or propel communicative language and social skills is a determinant factor in our daily lives (Prensky, 2010). In an educational context, new technologies offer wider knowldge and experiences, promote social interaction, foster autonomous behaviors and increase learners ecouragement to learn (Castells, 2003; Dudeney & Hockly, 2007; MEN, 2005; Prensky, 2010;).

One of the most striking features when promoting the use of social networks, web 2.0 tools and virtual platforms, refers to the possibilities that teachers find to foster the writing production. Most of the interactions that students have is written, it creates more opportunities to reinforce learners' language skills and they feel more motivated to learn (Roger, Kagan & Kagan, 1992). The use of Storybird to do collaborative writing when learners create narrative texts, offers possibilities to reinforce specific aspects of the writing ability, and the motivation towards their learning process increases as well.

Theoretical considerations

The growing interest related to the promotion of collaborative tasks to stimulate interaction and encourage critical thinking skills in the language classroom has expanded innovative views and perspectives towards second language learning and the internet use (Dudeney & Hockly, 2007). The internet became the learners' interactional scenario where most of their social relationships take place, they find themselves immersed in a new world and their needs and interests are defined by that world (Prensky, 2010). Moreover, Castells (2003) and Tapscott (2009) argue that the internet use has a positive effect on the social interaction because it increases the effects of sociability.

With regards to language learning, Scrivener (2005) strongly believes that it must be associated with real life experiences so that learners exchange language with specific communicative purposes at any context (p. 32). Thus, if the internet became learners' new world and reality, teaching practices should go far beyond and introduce the use of web tools to learn. When learners use social networks and websites to share experiences, points of view and ideas about the world, they interact using their written language naturally. In that sense, teachers and researchers must contemplate the idea of exploring ways to take advantage of the written language that is produced online, and promote more writing tasks and CW experiences online.

Computer Assisted Language Learning CALL

CALL makes reference to software applications or programs that integrate interactivity to promote language learning and teaching (Davies, Walker, Rendall, & Hewer, 2010). It is a subject intertwined with computer science but its main focus on applied linguistics makes it useful for language teachers. It involves any process in which a learner uses a computer and improves his or her language (Beatty 2003). CALL consists of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) applications that go from the traditional to the most recent methodological approaches.

Thomas & Reinders (2010) highlight three specific evolutionary stages in CALL which go from the basic drill-and-practice programs to web learning environments and web-based distance learning. In addition, it is esential that language instructors make important preliminary decisions before using technology in the classroom, chose the appropriate tool, pedagogical approach and methodology (Levy, 2006).

CALL research has been longer associated with the evolution of ICT and learning methodologies. Although much CALL research has been carried out at a micro-level intertwined with studies based on Task Based Language Teaching (TBLT), researchers have identified and learnt principles for learning tasks design in multimodal e-learning environments (Thomas & Reinders, 2010). Since CALL is focused on second language learning, its use needs to be reinforced and updated, involving current approaches to language learning and teaching (Hubbard, 2009, p.1).

Collaborative Writing (CW)

The CW has widely been studied by researchers and educators interested in analyzing the benefits that these experiences bring to the language classroom. Most CW practices go back more than 20 years in time when the use of the internet and technology barely influenced language learning. Research studies about writing skills and conceptions about interaction were based on the role of collaboration within the classroom and paper based tasks. However, those ideas about CW are still valid and many concepts, strategies and tasks are being adapted to the new emerging learning environments.

Kessler (1992), Nunan (1999) and Harmer (2004, 2007) define the CW experience as an opportunity to enhance writing and increase academic achievement in groups. Harmer (2004) affirms that "successful collaborative writing allows students to learn from each other" (p. 73), therefore, it also fosters the negotiation of meaning when learners go through each writing production stage collaboratively. There is space to share personal experiences and provide functional approaches to use language with objectives, strategies and stages defined by learners and teachers. Although there might be learners who still prefer working alone (Brown, 1994), their will to take part in CW experiences could be controlled by the teacher (Schwartz, 1998). Therefore, it is possible to intertwine collaborative and individual work and learners can work in isolation along some stages of the process (Elbow 2000). CW might entail many benefits if learners' needs and characteristics are cosidered when outlining lesson plans.

The benefits that CW embodies go further since learners develop interactional and social skills. The main concern is deciding on the type of tasks and aspects to reinforce and then, creating and/or promoting learning activities that encourage learners to interact and learn. When having learners doing CW, they excel above and beyond the individual knowledge; it offers advantages because more ideas and unlimited creativity emerge (Harmer, 2007, p. 329).

Web 2.0

When Tim Berners-Lee created the first browser interface, citizens around the world were able to access what had exclusively been used for military and academic purposes (Vallance M., Vallance K. & Masahiro, 2009, p. 7). That graphical browsing built on the Internet, known as web 1.0, was planned with the purpose of connecting people in an interactive space (Laningham, 2004, 46). However, most web 1.0 tools did not offer interaction between users because there was not possibility to modify, complement or create content.

Later on, the creation of web 2.0 tools led people to interact, the improvements and innovative technological advances resulted in the creation of a social web (Pegrum, 2009, p. 21). The perspectives towards the use of the Internet and the pedagogical implications that emerged, changed educators' perspectives towards collaborative tasks development (Pegrum, 2009, p. 21), learners were able to share opinions on blogs and also work together in the creation of definitions to words, biographies, stories, bibliographies and also music. The web 2.0 advances included: high speed, free web based software and applications, platform based services, users generated content, complex social interactions, and new business models (Peachey, 2009).

The use of web 2.0 tools generates a constructivist approach to language learning and teaching because learners focus on constructing knowledge and not receiving it; on thinking and analyzing, not memorizing; understanding and applying, not repeating back; and being active, not passive (Vallance Vallance & Masahiro 2009). Learners improve their communicative and social skills due to their exposure to diverse cultures and a wider range of communication styles (Ding, 2003).

Diverse research studies that include CW and the use of web 2.0 tools show learners' improvements in their writing skill proficiency. Beltrán (2010) shows how the use of CW to write digital stories promotes learners' self expression and helps them improve their writing skill. Consequently, it enhances the group dynamics, negotiation and cultural knowledge of the world. Moreover, Beltrán (2009), shows how the use of "Hot Potatoes" helped elementary students improve their spelling, vocabulary, and awareness of simple sentence construction.

A study carried out at La Sabana University shows that the web 2.0 tool "WebQuest" designed to promote critical thinking and collaboration, helped learners to improve their language skills and led them to increase autonomous behaviors (Jimenez, 2009). Elola & Oskoz (2010) demonstrate how the use of wikis and chats has brought new considerations in terms of CW, the use of wikis and chats helped learners to concentrate on their writing tasks when they did CW.

Storybird

Storybird is a web 2.0 tool created by Mark Ury that supports the collaborative storytelling with the use of art galleries that inspire people to create stories (Storybird, n.d; Nordin, 2010). It is available at www. storybird.com and learners can activate a free personal account to write narratives using images to create storyboards. When creating a storyboard, learners can discuss what they want their story to say, how to structure it and what images to use. The creation of storyboards as a prewriting strategy helps learners develop their writing skill (Linares, 2010). Before the invention of web 2.0 tools, digital storyboards were likely to be created by using pictures and/or images from the internet, nowadays web 2.0 tools like Storybird can provide the images learners need, systematically organized.

When working on Storybird, learners decide whether writing the story at the same time working synchronously in the classroom, or at home working asynchronously online by switching turns until the end of the story. Storybird has a huge list of galleries, the images can be arranged in slides as preferred and students are able to modify its content. Educators might find it useful at any educative level, from primary school with literacy purposes where English is spoken as the native language, up to higher education and English courses for ESL or EFL students. Avery (2011) outlines that "Storybird is an extremely engaging site that allows students to focus more on the content of their writing rather than drawing pictures."

Although no previous research projects are found about Storybird and the promotion of CW, educators' opinions towards its use demonstrate that it is enriching for literacy and storytelling. Dabbs (2011), Storybird (n.d.) and Nordin (2010) believe that Storybird encourages creativity and it is fun for any group of learners. It brings learners' abstract thoughts to real life (Dabbs, 2011) and helps students to "learn effective communication and collaboration" (Nordin, 2010, p.4).

Methodology

Bearing in mind the need to witness learners' improvements regarding their writing skills and evaluate the pedagogical intervention suitability through the whole process, the interventional principles of action research were the most convenient because it defines the teachers' role as an observer who collects data reflecting and redirecting thoughts based on a reflective teaching practice (Norton, 2009). Therefore, it brings action and reflection, theory and practice, and in participation with others, the pursuit of practical solutions to issues (Reason and Bradbury, 2006). The questions to answer were:

- What changes are evident in EFL upper intermediate students' writing skill when they write narrative texts collaboratively supported by the web 2.0 tool Storybird?

- What insights emerge from the participants with regard to the use of Storybird and collaborative writing for the creation of narrative texts?

Pedagogical intervention

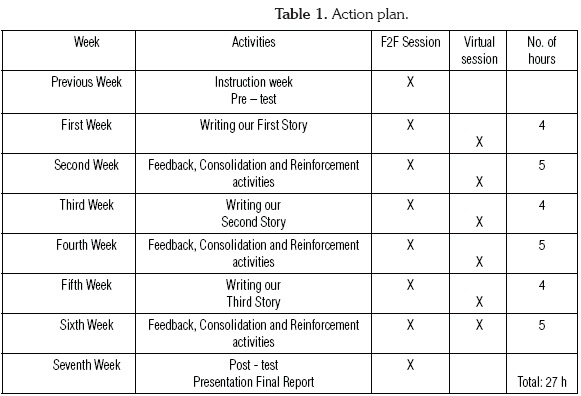

The pedagogical model based on a collaborative strategy for the production of stories supported by Storybird emerged from the learners' necessity to improve their narrative skills in short time. There were two pedagogical intervention cycles, the first one from October to November 2010, and the second one from March to April 2011, with the purpose of corroborating the findings and supporting the validity of the study. Since the learners who took part in the study were attending their English classes 6 hours per week, the researcher combined online and face-to-face sessions so that learners did not have to attend to face-to-face sessions 4 more hours. Along the two pedagogical interventions, learners were exposed to 8 weekly faceto-face hours of instruction and 2 or 3 hours of online work. The time they spent on this study was 27 hours apart from their 48-hours English course in a period of 2 months.

The two pedagogical intervention cycles took 8 weeks (table 1). The action plan followed the process approach to writing suggested by Harmer (2004): (a) pre- writing, (b) drafting, (c) revising and (d) editing. Learners did every step collaboratively with another peer and every week they chose a different mate to work with. Pre tests were used the first week and posttests the seventh week.

Learners wrote 3 stories following the same patterns and strategies:

- Synchronous CW in a F2F class onto Storybird for the pre-writing section where learners negotiated and talked about the topic of the story, they dragged and arranged the images they would probably use to create their Storyboards. They talked about the events to happen, defined an introduction, a problem and a resolution.

- Asynchronous CW onto Storybird: One student started writing the story and then, they switched their stories 3 or 4 times being likely to modify the writing content if they wanted.

- When learners finished writing their stories, the tutor met the class to deliver feedback. Then, learners edited their drafts improving their tasks to hand in a final version and publish it onto Storybird.

Context

The students who volunteered to take part of this study were enrolled in the general English language proficiency program at ILUD Bogotà, Colombia. Although the University branch is located in the 2nd zone of Bogotá, learners attending the two-months course levels were members of diverse social status levels, public and private universities, schools and institutions.

Participants

The two groups of learners who volunteered to take part of this study were adult learners who needed to pass the FCE exam as a graduation requirement, to get a job promotion and/or to get an international certificate. Because of their careers, jobs and families, the time they could invest was limited and that is why they attended face to face sessions two hours a week.

The first group with fifteen learners aged from 18 to 24 years old, was conformed by 8 women and 7 men, 13 were undergraduates and 2 were independent workers. They took lessons from October to November 2010 in the afternoon from 4:00 to 6:00 p.m. The second group with 10 learners aged from 23 to 27 years old, was conformed by 7 women and 3 men, 4 were undergraduates and 6 workers. They took class sessions from March to April 2011 at night from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. Although the two groups of learners were doing a training course to take the FCE exam, their linguistic, affective and communicative needs varied. Most learners attending in the afternoon along the first cycle were young undergraduates and most of the students attending at night were middle aged workers. However, after analyzing data the findings showed similar outcomes.

The researcher

The researcher's role was as participant and researcher. The teacher was an observer who collected data reflecting and redirecting thoughts based on a reflective teaching practice (Norton, 2009). Therefore, the reasearcher designed and directed the lessons and at the same time collected data.

Data Collection Instruments and procedures

The data collection instruments were mainly reflective instruments and the use of pre and posttests helped to corroborate the participants' insights that emerged in relation to their improvements and perceptions.

Reflective Journal

Each session the researcher reflected on the learners' improvements, behaviors and needs. Therefore, reflections on "thoughts, feelings, motives, reasoning processes and mental states to determine the ways in which these processes and states determine his or her behavior" (Nunan, 1992, p. 115), led to improve future interventional procedures and sessions.

Focus groups

There was one focus group in between the 2 pedagogical intervention cycles and another one at the end of the pedagogical intervention. The focus groups were applied with a small number (3-4) of individuals who provided information during interactive group discussion (Popham, 1993). Learners talked about their feelings and the extent to which Storybird and the CW strategy had helped them to overcome their issues. Since learners reflected in small groups, they gained more confidence to answer questions and share ideas.

Survey

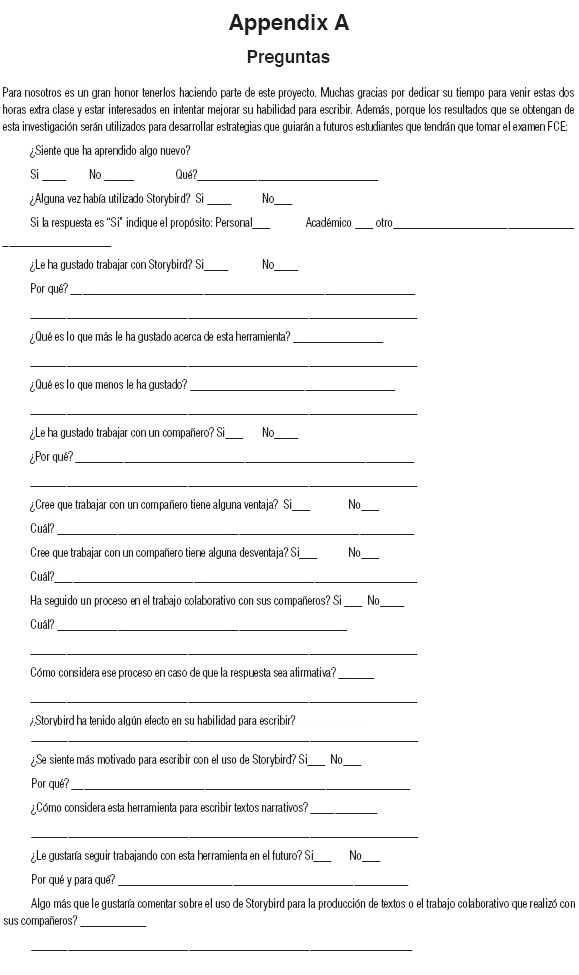

It was applied at the end of the intervention cycles in order to validate the data analysis (Appendix A), the information was corroborated and/or complemented with the reflective journal, the focus groups and the pre and posttests. Phillips & Stawarski (2008) believe that when using focus groups and surveys there is specific follow-up on the initial results.

Pre and posttests

Pre and posttests were used to measure the knowledge learners gained from participating in the course and also answer the first research question. The surveys, focus groups and the reflective journal helped the researcher to answer the second question outlining the impressions that emerged with regard to the CW and Storybird.

Ethical concerns

- As suggested by Norton (2009) and Wallace (1998), the following principles were considered: b) The learners who took part of this project did it of their own free will.

- There was consent and permission from ILUD's directives and the participants to carry out the 2 pedagogical interventions.

- Learners knew that the results were to be published but their names were not. The researcher would use nicknames instead.

- The ideas presented in this document and the activities used in the pedagogical implementation that did not belong to the researcher were documented and referenced.

- The use of good manners and consideration of others was highly significant and the appropriate consent forms were designed concerning the recommended protocol.

Findings

The data analysis procedures were based on the grounded approach because data was constantly and systematically compared and that analysis supported the emerging theory (Strauss and Corbin, 1990; Norton, 2009; Auerbach & Silverstain, 2003). Through the axial coding process, the emerging categories were related following an inductive and deductive method (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). This qualitative analysis implied interpreting, understanding, explaining and generating theory (Auerbach & Silverstain, 2003).

The core category that emerged from the axial coding process was called "the collaborative creation of narrative texts using Storybird encourages learners to write leading to improvements on vocabulary and attempts to use more complex grammar." Therefore, two subsidiary categories emerged "Enhancement of specific sub-skills of the written language," and "Increased motivation and autonomy towards the writing process,"

Enhancement of specific sub-skills of the written language

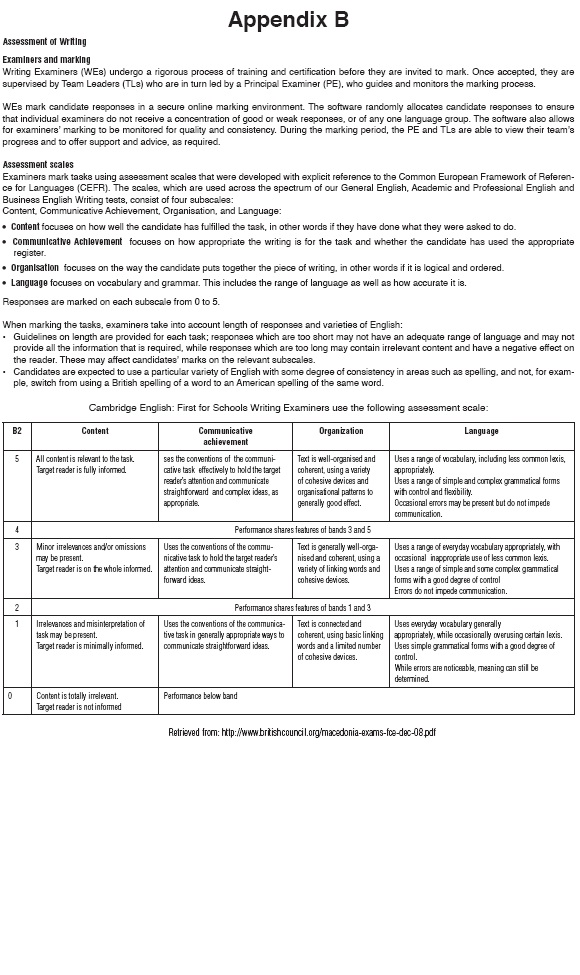

This subsidiary category includes essential aspects concerning the written production and the noticeable improvements that learners had in regard to in their writing skill. According to the "General Mark Scheme" (Appendix B) provided by the British Council to assess B2 writing tasks, the candidates who use more vocabulary and make attempts to use complex language forms, are awarded with a higher grade (Band 4). Bearing this in mind, learners showed improvements that lead them to perform better. Elola & Oskoz (2010) argue that it is still uncertain the extents to which learners improve their writing skill using web 2.0 tools to do collaborative or individual assignments in terms of fluency, accuracy and complexity. Nonetheless, Beltrán (2010), Aguirre (2010), Jiménez (2009) and Linares (2010) show how the promotion of collaborative tasks through the use of web 2.0 tools help learners strengthen their language in specific and varied aspects.

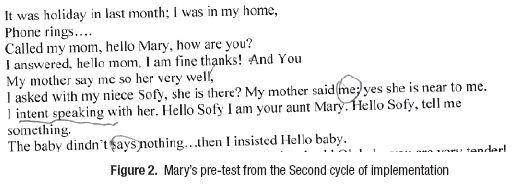

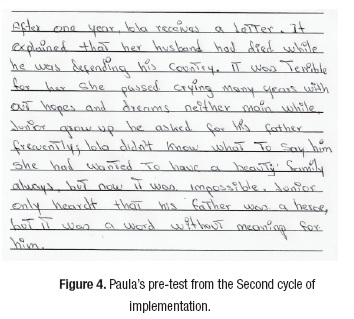

Based on the comparative analysis of pre and posttest, in which learners created a story based on a real task from the FCE exam, they were clasified into three groups according to their performance. In the first group, learners' pre tests barely communicate messages. Although they made attempts to write clear sentences, the ideas were inadequately organized, the linking devices rarely appeared, and the range of structure and vocabulary was narrow. They scarcely used paragraphs and some errors distracted the reader and impeded communication. Furthermore, the attempts at appropriate register and format were unsuccessful or inconsistent and there was little evidence of language control (figure 2).

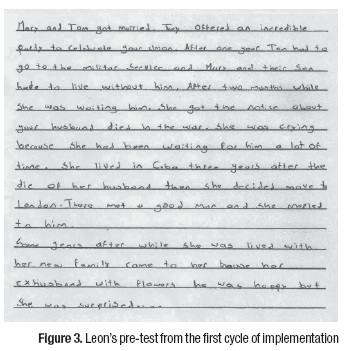

The second group of learners' pre tests, with a borderline or pass mark in their performance, demonstrated they knew how to write a story since they tried and covered the content and wrote an appropriate introduction, a problem and an expected resolution to the problem. Although some learners wrote sentences that impeded the text comprehension the very first time the reader read it, there was an effect on the target reader. The ideas were organized adequately although the range of structure and vocabulary was limited. Some errors that occurred distracted the reader and obscured communication at times (figure 3).

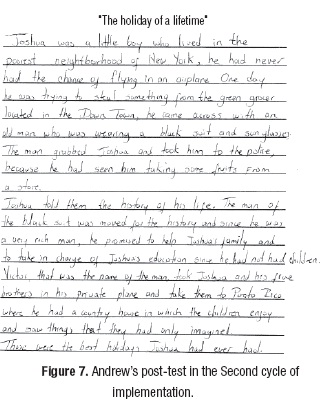

The third group of learners' pre tests, with the strongest writing tasks, showed an efficiently arranged story and it achieved the desired effect on the reader. All the points required in the task were included and the ideas were organized adequately with the use of linking devices. A number of errors especially when they used narrative tenses were present, but they did not impede communication. They made reasonable attempts at using appropriate register and format which was appropriate for the purpose of the task and the audience (figure 4).

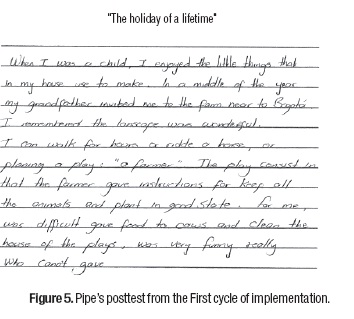

The posttests analysis showed that the first group of learners still presented issues and few of them barely tried to organize ideas logically using linking devices. Although they had to work harder, their ideas were expressed more logically using punctuation marks and capital letters efficiently. Therefore, most errors were attempts to use more complex language forms and vocabulary. Their writing skill slightly improved since in most cases they showed more coherent texts even though they still needed to reinforce structures of the language and expand their vocabulary (figure 5).

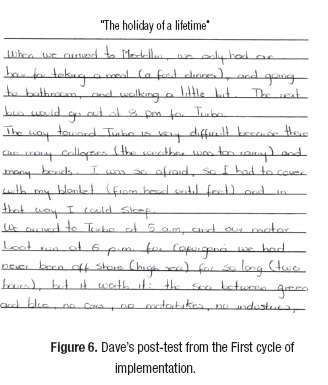

The second group of learners' posttests, achieved the desired effect on the reader and had a good introduction, problem and creative problem resolution. There were still issues tied to the use of narrative tenses and grammar categories. However, they were attempts to use more complex language forms and new vocabulary. Most ideas were organized adequately and they used linkers and an adequate range of structure and vocabulary. Some errors were present but they did not impede communication. The format and register were appropriate and the target reader could be informed (figure 6).

The posttests of the group of learners with the strongest writing tasks achieved the desired effect on the target reader and all the content points were covered. Ideas were clearly organized and they used suitable linking devices and a good range of structure and vocabulary. Generally, the language was accurate and any errors that did occur were mainly due to attempts at more complex language. Register and format were, on the whole, appropriate to the purpose of the task (figure 7).

The pre and posttest analysis showed that the learners made improvements in their vocabulary and deepened on certain grammatical aspects of the language. Although most of the times the attempts to use complex grammar ended up in errors, international institutions like the British Council encourage markers to value learners' attempts to use more complex structures and lexicon because that constitutes a difference in the candidates' grades. Learners who make attempts to use more complex language forms and vocabulary are more likely to get a higher grade.

In general, learners expressed that the experience with the CW and the use of Storybird had helped them to discover and learn new words and grammar.

Q: ¿Sienten que han aprendido algo Nuevo? (Do you think you have learnt something new?)

"Si pues en mi caso sí he aprendido algo nuevo sobre todo vocabulario y gramática pues que creo que en estos niveles es lo que más nos hace falta por lo menos a mí que es vocabulario" (Addy. Focus group: May 3rd 2011). (Well yes, in my case I have learnt something new but overall vocabulary and grammar, I think that in these levels what is missing, or at least for me is vocabulary"

Evidence from surveys:

Q: Storybird ha tenido algún efecto en su habilidad para escribir? (Has Storybird had any effect on your writing skill?)

Sí, vocabulario y gramática (yes first question, vocabulary and grammar). (Dave, end-of-term survey. Second cycle of implementation. Nov 18th 2010).

Ayuda a mejorar y ampliar el vocabulario. (It has helped me to improve and expand vocabulary). (Ocampo, end-of-term Survey. May 19th 2011).

Reflective Journal Perceptions:

"Their vocabulary is expanding enormously when they write they stories and when they have to negotiate meaning and/or correct their partners' stories and look for new words". (Reflective Journal May 9th 2011).

Increased motivation and autonomy towards the writing process

This subsidiary category is supported by insights retrieved from surveys, focus groups and the reflective journal. A general analysis demonstrates that learners enjoyed working with Storybird collaborativelly, for most of them, the work they did with their peers using a web 2.0 tool added a new enriching experience to their lives. The CW they did following a process approach mediated by Storybird led learners to rise awareness about their writing skills and their weaknesses and strenghts.

Learners increased their eagerness to do their writing tasks and perceptible autonomous behaviors emerged when learners self and peer corrected partners. They felt more motivated to do their writing tasks because they knew that somebody else was going to read them. Richards & Rodgers (2001), Brown (1994) and Harmer (2007) claim that the collaborative learning experiences enhance students' motivation and reduce stress creating a positive affective climate.

The use of computers was motivating and it guided learners to develop autonomous behaviors to enhance their own learning (Prensky, 2010; Chapelle, 2003) when they made decisions about the online resources to use, the stories creation process, and when and how to work. In addition, increased autonomy is probably the major effect that the collaborative learning experiences have (Totten, Sills, Digby & Russ, 1991; Benson, 1996 and Little, 2000).

Q: ¿Cómo se han sentido al ver sus historia publicadas y tal vez comentadas por otras personas de diferentes partes del mundo? (How did you feel when you saw the stories you published commented by different people around the world?)

"Siento que me ha retado a sacar todo lo que tengo y además a consultar porque uno también sabe que lo va a publicar."(Addy. Focus Group. May 5th 2011). (I feel that it has helped me to give the best from me, and also to consult because one knows that it is going to be published)

Q: ¿Qué piensan de las actividades desarrolladas en el aula de clase en las que se incluyen narraciones? (What do you think about the activities developed in class in which there are narratives?)

"Pienso que el uso de Storybird motiva mucho para que con mi compañero creemos las historias, y lo bueno de las actividades y estrategias es que son buenas es que ya sabemos cómo hacerlas solos en cualquier momento." (Jhost. Focus Group: May 5th 2011) (I think that use of Storybird encourages us to create stories, and the good thing about the activities and the strategies is that they are great and we know how to do them on our own at any moment).

Q: … ¿Es decir que se siente más motivado para escribir cuando utiliza Storybird? ( What you mean is that you feel more encouraged to write when you use Storybird?)

"Sí además porque sobre todo la parte de la corrección cuando uno se siente leído y corregido por otro ya sea por el profesor o por el compañero entonces eso motiva a uno a hacer las cosas mejor." (Dave. Focus Group. Oct 16th 2010). (Yeah, especially in the correction section because when you feel read and corrected by another partner or the teacher, that motivates you to do the things better.)

"When learners were correcting their peers I enjoyed seeing how confident and autonomous they had become as they started to assess their peers and their own tasks with their own criteria. One learner told me that at the beginning he was shy but he demonstrated he had become more confident because he was correcting his partners' writings with certainty in his appreciations." (Reflective Journal. April 4th 2011).

Storybird as a web 2.0 tool fostered creativity and learners argued they felt encouraged to write their stories not just because Storybird is an Internet tool but because they think that the idea of using images contributes to the fluency in the production of ideas in a creative way (Dabbs, 2011; Storybird, n.d; Nordin 2010).

Q: ¿Storybird ha tenido algún efecto en su habilidad de escribir? (Has storybird had an effect in your writing skill?

"Mejorado mi lenguaje además de expandir los límites de mi imaginación en cuanto a la creación de historias." (Lily. Survey, November 18th 2010). (it has improved my language apart from expanding my imagination limits regarding the stories creation).

Q: ¿Qué es lo que más le ha gustado de Storybird? (What have you liked the most about Storybird?)

"Me gusta que me ayuda a ser más fluida cuando escribo una historia. Es más fácil cuando uno tiene las imágenes ya organizadas." (Dave. Survey, November 18th 2010). (I like it helps me to be more fluent when I write a story. It is easier when you have the sentences organized).

Q: ¿Sienten que han aprendido algo nuevo? (do you feel like you have learnt something new?)

"La herramienta nos anima a ser creativos en el momento de tratar de enlazar una idea con una imagen que estamos observando entonces nos anima a crear y a mantener la coherencia en un una composición."(Addy. Focus group. May 5th 2011) (It is a tool that encourages us to be more creative when we need to intertwine ideas with images, then it helps us to write a coherent composition)

When learners were doing the storybird I realized they wanted to do them and were absolutely encouraged because of their comment and the huge amount of ideas that came to their minds to write their stories (Researcher's Reflective journal, Nov. 1st 2010)

Conclusions

The CW strategy supported with the use of Storybird convey learners to improve specific aspects of the written language, they become more aware of the use of structures, improve their vocabulary and the attempts to write more complex sentences increase. In face-to-face or online sessions the CW leads learners to negotiate meaning, vocabulary and content. The negotiation process takes them to reflect on their written language and produce more ideas to write their stories.

When doing CW, learners' awareness towards the writing process grows and autonomus behaviors are noticeable when learners self and peer correct, and make decisions concerning the process to follow and the language to use. Learners reflect on the language, content and create meaning, and that is an esential variable that takes learners to expand their vocabulary and use more accurate and complex structures when doing narrative texts.

Motivation represents a defining factor because when learners feel motivated to learn, the results in terms of participation and writing production increase. Along the process, the participants felt encouraged to create their stories because storybird offers the possibility to do CW using art galleries to create storyboards, and that was new for the groups of learners. Therefore, by doing pair work, learners focus on what they want to do and how they want to do it, they are more likely to achieve their goals working with autonomy.

Since the use of storybird implies the creation of storyboards collaboratively, the use of images triggers creativity, learners are likely to write their stories deciding on the images to use. There is more production of language and more ideas emerge.

When learners use web 2.0 tools like Storybird encouragement increases together with the possibilities to develop Collaborative learning tasks autonomously. Moreover, what enriches and benefits the learning process and propels the improvement of language skills, is the strategy that the researcher uses rather than the use of the web 2.0 tools.

The outcomes depicted represent an opportunity to reflect about education and consider the promotion of experiences where learners have the chance to use diverse web tools. The use of the internet to develop learning tasks is encouraging for learners but demotivating when there is not support from the tutors. Nowadays there are many possibilities to promote online learning and prepare students for the real life; the challenge is to make sure that the learners truly feel they learn what they need when they need it, the way they need it.

Pedagogical Implications

Settings in which learners are called to interact mediated by the use of technology are appealing to them. They feel encouraged because it implies the possibility to learn or reinfornce knowledge in a different way. However, esential matters are to be considered by teachers regarding the strategies to follow when using web tool. Storybird is a web 2.0 tool which can be used to promote the collaborative creation of narratives but learners' success depends basically on the free will they have to make desicions along the process.

Educators might combine strategies and web tools to actually take learners to learn, there is not a web 2.0 that fits all the teachers and/or learners needs but the combination of different web tools might support language learning processes. At any research study researchers might feel encouraged to identify and use, from a huge variety of Internet tools, the one(s) that can appropriately help their learners to learn in their unique contexts.

What makes of Storybird an encouraging source to create stories, is the possibility that it offers to create storyboards. When having learners creating storyboards, they negotiate and create meaning by defining the context, the content, the situation and characters of a story. It is clear that Storybird is a tool that encourages learners to write collaboratively but people who might like working individually could do it as well.

Storybird can be used to follow a process aproach to writing, it is recommended to use the storyboards as a pre-writing activity in the classroom before learners go home and continue with the collaborative online work.

Limitations

This study was primarily limited by its short time. The improvements the researcher expected in terms of learners' writing production would have been different if the study had lasted more. The process led to improvements in various aspects but a longer study might enrich the experience and more improvements could be evident.

Larners could feel limited by the range of pictures offered by Storybird, although there is plenty of art, pictures are not appealing to learners at times. Therefore, if there is not motivation for learners to work with computers or they don't know how to do it, extra work is required and more challenges would emerge for the teacher along the study.

Further Research

Since Storybird and the use of CW go together, researchers might be interested in studying the differences between the promotion of CW through web 2.0 tools and without using them. In that sense, a suitable study could be an experimental research with a controlled group undergoing a traditional writing class and an experimental group using Storybird.

Researchers might plan an experimental research study where learners have the chance to use Storybird and a different web 2.0 tool to promote CW for the creation of stories. Moreover, researchers might include the use of other web 2.0 tools in the pedagogical intervention.

Notas

1First Certificate in English Exam (Designed to test B2 English Language Proficiency Level).

References

Aguirre, A. (2010). Writing hyperstories Collaboratively for an Authentic Audience. Universidad Distrital. Bogotá Colombia. [ Links ]

Auerbach, C., & Silverstein, L. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Avery, S. (2011, September 5). Storybird a Collaborative Storytelling Tool. Retrieved from http://techtutorials.edublogs.org/2011/09/05/storybird/. [ Links ]

Beatty, K. (2003). Computer Assisted language learning. England: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]

Beltrán, A. (2010). EFL University Learners Working Collaboratively with Digital Storyboards. Bogotá, Colombia: Universidad Distrital. [ Links ]

Beltrán, J. (2009). Using the Online Software Hot Potatoes to Help First Graders Develop beginning Writting. Chía, Colombia: Universidad de la Sabana. [ Links ]

Benson, P. (1996) Concepts of autonomy in language learning. In R. Pemberton, et al. (eds) Taking Control: Autonomy in Language Learning (pp. 27-34). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [ Links ]

Brown, H. D. (1994). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall Regents. [ Links ]

Castells, M., (2003). La Galaxia Internet: Reflexiones sobre internet, empresa y sociedad. Barcelona: Areté [ Links ].

Chapelle, C. (2003). English language learning and technology: Lectures on applied linguistics in the age of information and communication technology. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. [ Links ]

Davies G. Walker R., Rendall H. & Hewer S. (2010) Introduction to Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL). Module 1.4. In Davies G. (ed.), Information and Communications Technology for Language Teachers (ICT4LT). Slough: Thames Valley University [Online] [ Links ].

Dabbs, L. (2011, July 19). New teacher Boot Camp Week 3-Using Storybird. Retrieved from http://www.edutopia.org/blog/storybird-new-teacher-bootcamp-lisa-dabbs. [ Links ]

Ding, A. (2003). Theoretical and Practical Issues in the Promotion of Collaborative Learner Autonomy in a Virtual Self-access Centre. In B. Holmberg, M. Shelley & C. White, (Eds). Distance education and languages: Evolution and change (2005). Clevedon, Hants, England: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Dudeney, G., & Hockly, N. (2007). How to teach English with technology. Harlow: Pearson/Longman. [ Links ]

Elbow, P. (2000). Everyone can write: Essays toward a hopeful theory of writing and teaching writing. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Elola, I. & Oskoz, A. (2010). Collaborative Writing: Fostering Foreign Language and Writing Conventions Development. Language Learning and Technology, 14 (3), 51 - 71. [ Links ]

Harmer, J. (2004). How to teach writing. Harlow: Longman. [ Links ]

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching: DVD. Harlow: Pearson/Longman. [ Links ]

Hubbard, P. (Ed.) (2009). A General Introduction to Computer Language Assisted Language Learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning: Critical Concepts in Linguistics. Volume I. Advance online publication. Retrieved from http://www.stanford.edu/~efs/callcc/callcc-intro.pdf. [ Links ]

Jimenez, C. (2009). Webquests and the Improvement of Critical Reading Skills in a group of University Students. Chia, Colombia: Universidad de La Sabana. [ Links ]

Kessler, C. (1992). Cooperative language learning: A teacher's resource book. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall Regents. [ Links ]

Laningham, S. (2004). DeveloperWorks Interviews: Tim Berners-Lee. Retrieved November 13, 2011, from: http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/podcast/dwi/cm-int082206txt.html. [ Links ]

Levy, M., (2006). Effective Use of CALL Technologies: Finding the Right Balance. In Donaldson & Haggstrom (Ed). Changing language education through CALL (pp. 1-18). Abingdon, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Linares, A. (2010). Using Visual Literacy in a Sequence of Picture Stories to Write Narratives. Bogotá: Universidad Distrital. [ Links ]

Little, D. (2000) Learner autonomy and human interdependence: Some theoretical and practical consequences of a social-interactive view of cognition, learning and language. In B. Sinclair et al. (eds). Learner Autonomy, Teacher Autonomy: Future Directions (pp. 15-23). London: Longman. [ Links ]

MEN, (2005). Bases para una Nación Bilingüe y Competitiva. Ministerio de Educación Nacional. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from: http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-97498.html. [ Links ]

Nordin, Y. (2010). Web 2.0 and Graduate Research Storybird. Retrieved from: http://edpsychbsustudentwork.pbworks.com/f/3-StoryBirdWeb+2.0+and+Graduate+Research.pdf. [ Links ]

Norton, L. (2009). Action research in teaching and learning: A practical guide to conducting pedagogical research in universities. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Nunan, D. (1992). Collaborative language learning and teaching. Cambridge language teaching library. Cambridge [England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Nunan, D. (1999). Writing. Newbury House Teacher Development (Ed.), Second language and teaching (pp. 271-299). Boston, Massachusetts: Heinle & Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Peachey, N. (2009). Web 2.0 Tools for Teachers. Retrieved from: http://www.scribd.com/doc/19576895/Web-20-Tools-for-Teachers. 28 Nov. 2010. [ Links ]

Pegrum, M., (2009). Communicative Networking and Linguistic Mashups on web 2.0. In M. Thomas (Ed.), Handbook of research on Web 2.0 and second language learning (pp. 20-41). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference. [ Links ]

Phillips, P. P., & Stawarski, C. A. (2008). Data collection: Planning for and collecting all types of data. San Francisco: Pfeiffer. [ Links ]

Popham, W. J. (1993). Educational evaluation. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Prensky, M. (2010). Teaching digital natives: Partnering for real learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. [ Links ]

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2006). Handbook of action research. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Roger E., Kagan O. & Kagan S. (1992). About Cooperative Learning. In Kessler (Ed.), Cooperative Language Learning: A Teachers' Resource Book (pp. 1-30). Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall Regents. [ Links ]

Schwartz, D. (1998). The Productive Agency that Drives Collaborative Learning. In Dillenbourg (Eds.), Collaborative Learning: Cognitive and Computational Approaches (pp. 197-218). Amsterdam: Pergamon. [ Links ]

Scrivener, J. (2005). Learning and Teaching. A Guidebook for English Language Teachers. Macmillan books for teachers. [ Links ]

Strauss, A & Corbin, J. (1990) Basics of Qualitative research. Grounded theory applications and techniques. London: Seige Publications. [ Links ]

Storybird, (n.d.). Retrieved April 4, 2012, from http://educ5553.wikispaces.com/file/view/Storybird.pdf -Principio del formulario. [ Links ]

Tapscott, D. (2009). Grown up digital: How the net generation is changing your world. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Thomas, M., & Reinders, H. (2010). Task-based language learning and teaching with technology. London: Continuum. Final del formulario. [ Links ]

Totten, S., Sills, T., Digby, A., & Russ, P. (1991). Cooperative learning: A guide to research. New York: Garland. [ Links ]

Vallance M., Vallance K. & Masahiro M., (2009). Criteria for the Implementation of Learning Technologies. In Thomas, M. (Ed.), Handbook of research on Web 2.0 and second language learning (pp. 1-19). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference. [ Links ]

Wallace, M. J. (1998). Action research for language teachers. Cambridge teacher training and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]