Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

Print version ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.16 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2014

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.1.a07

REFLECTION ON PRAXIS

http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.1.a07

Teaching culture in Colombia Bilingüe: From theory to practice1

La enseñanza de la cultura en Colombia Bilingüe: de la teoríaa la práctica

Yamith José Fandiño Parra, M.A.

Universidad de La Salle

Bogotá, Colombia

yfandino@unisalle.edu.co

Received: 15-Jul-2013 / Accepted: 28-Feb-2014

To cite this article

Fandiño, Y. J. (2014). Teaching culture in Colombia Bilingüe: From theory to practice. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 16(1). 81-92.

Abstract

The main topic of this paper is concerned with the incorporation of culture into the teaching of English as a foreign language (EFL) within the context of Colombia Bilingüe. More specifically, some consideration will be given to what culture is, how it can be taught, and what Colombian authors have pointed out in terms of the difficulties and complexities of working with culture in the EFL classroom. It will be suggested that teaching culture is not synonymous with promoting English sociocultural domination or adapting ethnocentric practices, but mainly approaching and reflecting upon one's and others' beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors which are intertwined with language itself. The main premise of the paper is that effective teaching of culture can be achieved if the Colombian EFL community strives to construct a coherent discourse that allows developing teaching models and learning experiences within the theoretical framework of the postmethod condition, world Englishes, and critical multiculturalism. Ultimately, such discourse can encourage Colombian EFL teachers to explore and implement five teaching strategies to engage learners in experiences designed to help them interact successfully with people with different cultural backgrounds.

Key Words: Colombia Bilingüe, critical multiculturalism, culture, postmethod, teaching strategies, world Englishes.

Resumen

El tema principal de este artículo se relaciona con la incorporación de la cultura en clases de inglés como lengua extranjera (ILE) dentro del contexto de Colombia Bilingüe. Más concretamente, se hace una aproximación al concepto de cultura, las formas en las que se puede enseñar y las posiciones que algunos autores colombianos han planteado en términos de las dificultades y complejidades de trabajarla en los salones de inglés como lengua extranjera. Se sugiere que la enseñanza de la cultura no es equivalente a la promoción de una dominación sociocultural inglesa o la adaptación de prácticas etnocéntricas, sino sobre todo consiste en el acercamiento y la reflexión sobre creencias, actitudes, y comportamientos propios y de otros, que se entrelazan con el lenguaje mismo. La premisa principal de este trabajo es que la enseñanza efectiva de la cultura se puede lograr si la comunidad colombiana de enseñanza de inglés se esfuerza por construir un discurso coherente que permita el desarrollo de modelos de enseñanza y experiencias de aprendizaje en el marco teórico de la condición posmétodo, ingleses mundiales, y multiculturalismo crítico. En última instancia, este discurso puede hacer que los profesores de inglés colombianos exploren y pongan en práctica cinco estrategias de enseñanza para involucrar a los estudiantes en experiencias diseñadas para ayudarles a interactuar con éxito con personas con diferente bagaje cultural.

Palabras clave: cultura, Colombia Bilingüe, posmétodo, ingleses mundiales, multiculturalismo crítico, estrategias de enseñanza.

Introduction

At present, culture, language, and thought strongly relate to one another, interacting in different ways and at different levels. Recent findings from cultural neuroscience suggest that culture shapes the mind and thoughts of individuals. On the one hand, it influences the cognitive schema or self-construal style that people use to think about themselves and their relationships with others. On the other hand, it affects their most basic mental tasks and processes such as problem solving, object perception, and language processing (Ambady, 2011).

In this regard, Brown (2006)stated that culture is an integral part of the interaction between language and thought. To him, cultural patterns, customs, and ways of life shape the way we think and understand the world around us and at the same time, it is reflected in the way we use language. Similarly, Johnson (2005) maintained that language learning consists of more than the ability to understand new linguistic structures. Indeed, the coding and decoding of communicative acts require an understanding and appreciation of the cultural context in which they occur. In sum, an intricate interplay of culture, language, and thought exists which demands from EFL teachers both solid theoretical knowledge and strong practical skills.

Definition of Culture

Undoubtedly, culture plays a central role in the teaching and learning of foreign languages. However, its understanding and implementation in the foreign language classroom is not an easy task as EFL teachers can find a myriad of perspectives and concepts defining culture and how it can be taught. For anthropologists and other behavioral scientists, culture consists of the full array of learned human behavior patterns (Tylor, 1871). Tylor defined culture as a complex whole that includes knowledge, belief, art, law, morals, custom, and other capabilities and habits acquired by individuals as a member of society. Hofstede (1980) defined culture as a "collective programming of the mind that distinguishes members of groups and it is passed from generation to generation" (p. 51). Nowadays, most authors agree that "culture can be understood as the shared patterns of behaviors and interactions, cognitive constructs, and affective understanding that are learned through a process of socialization" (CARLA, 2011, P. 1).

In the field of language teaching, Halverson (1985) asserted that a basic distinction can be made between what is sometimes referred to as big C culture (also called culture MLA: music, literature, and art of a country) and little C culture (also called culture BBV: beliefs, behaviors, and values). Furthermore, Hinkel (2001) distinguished between invisible and visible culture. Visible culture includes cuisine, festivals, customs, and other traditions, whereas invisible culture manifests itself through socio-cultural norms, worldviews, assumptions, and values. Bilash (2011), on the other hand, claimed that recent views of culture include the three P's of culture: products, practices, and perspectives. In this view, products are understood as the big elements of cultures such as pieces of literature or works of art. Practices, on the other hand, are thought of as the little elements of culture; e.g., traditions related to holiday celebrations or socially appropriate gestures for dating. Finally, perspectives are the underlying values and beliefs of a people. For instance, youth valued over age or valuing sports over education.

Other teachers regard culture as a fifth language skill. In this line of thought, and based on the international role of foreign languages and globalization, Tomalin (2008) explained that learning a language can help to learn a set of cultural features, but it does not teach one cultural sensitivity and awareness. In order to develop cultural consciousness, culture needs to be addressed explicitly and systematically so that language learners acquire the necessary mindset and techniques that allow them to adapt their language use according to particular ways of thinking, feeling, and acting. As a result, Tomalin maintained that teachers should help students build up a set of cultural abilities which involves understanding cultural knowledge (knowledge of culture's institutions), cultural values (what people think is important), cultural behavior (knowledge of daily routines and actions), and cultural skills (the development of intercultural sensitivity and awareness).

According to Agudelo (2009), the search for an articulate curricular framework between language and culture in EFL teaching has brought about the appearance of the concept of intercultural competence. Following Jensen (1995), Agudelo states that this competence consists of "the capacity to establish intercultural relationships on both emotional and cognitive levels, as well as the ability to stabilize one's self-identity while mediating between cultures" (p. 191). Concretely, Agudelo adopted the conceptualization of intercultural competence offered by Byram, Gribkova, and Starkey (2002). This concept includes five savoirs:

- (a) savoir être (intercultural attitudes such as curiosity and openness),

(b) saviors (knowledge of social groups, their products and practices),

(c) savoir comprendre (skills of interpreting and relating documents and events from another culture),

(d) savoir apprendre/faire (skills of discovering and interacting to acquire new cultural knowledge and practices), and

(e) savoir s'engager (critical cultural awareness to evaluate perspectives, practices and products).

From the postmodern point of view, authors tend to review the concept of culture in terms that incorporate it into a study of power. Coombe (1991) stated that "postmodernism asks one to regard culture as a meaning-making process tied to relations of struggle that emerge in everyday situations" (p. 189). In other words, postmodernism demands one to understand cultural practices as result of confrontation that takes place within specific local contexts and historical conjunctures. On the other hand, Taylor (2000) maintained that postmodern culture represents instances of historical and ideological revolution in which modernist emphasis on coherence and universality is viewed as contradictory and repressive. Instead, this definition of culture values the particular over the global and the fragment over the whole in order to take into account the plurality of human experiences and the multiplicity of reality's alternatives.

The teaching of culture

When discussing how to teach culture, Thanasoulas (2001) affirmed that two perspectives have influenced the teaching of culture in EFL: the factual perspective and the interpretive perspective. The former is concerned with the transmission of facts regarding the target civilization such as institutional structures, literature and arts milestones, and customs and folklore of everyday life. The latter, on the other hand, is concerned with the establishment of points of reference between one's own country and that of the target culture. Concretely, Following Singhal (1998), Thanasoulas stated that the teaching of culture should basically consist of giving students a true representation of another culture and language by fostering empathy with the cultural norms of the target community and awareness of one's own cultural logic (p. 19). In other words, teaching culture should contribute to learners' acknowledgement of self and understanding of others.

From a more instructional view, Peterson and Coltrane (2003) claimed that EFL educators needed to use strong teaching strategies in order to both incorporate cultural objectives and activities and to enrich and inform the teaching content of their lessons. Among other things, these authors recommended using proverbs, role-playing, culture capsules, literature, films, and ethnographic studies. Furthermore, Clouet (2006) contended that cultural learning could be truly meaningful when students are taught through a comparative and contrastive approach. Not only can the process of comparing and contrasting help students attain a better appraisal of the target culture, but it can also help them achieve a greater awareness of their own culture. Ultimately, students may be able to go beyond working with cultural facts and move towards experiencing greater cross-cultural understanding.

In regards to approaching culture in EFL classes, Saluveer (2004) asserted that foreign language education should provide learners with opportunities to develop cultural knowledge, cultural awareness, and cultural competence in order to reach a better understanding of the foreign culture as well as appropriate comprehension of their own culture and the self. Working with cultural knowledge consists of receiving information about the target culture in the form of descriptions, explanations, statistics, examples, and anecdotes. This information is gained from other people in a static and predetermined way. On the other hand, working with cultural awareness involves developing a consciousness about one's own culturally induced behavior as well as that of others. It implies an ability to reflect on one's cultural identity, values, and beliefs in order to understand those of one's interlocutors. Cultural awareness emerges from one's own personal and direct perceptions, experiences, and interactions. Finally, cultural competence can be defined as the sum of knowledge, skills, and characteristics that allow one to perform intercultural actions (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 43). According to Byram and Zarate (1997, as cited by Ho, 2009, p. 65), this competence highlights the mediation between different cultures so that one can assume another perspective and adjust one's behaviors, values and beliefs. Interculturally competent learners, therefore, need to be able to learn to use a series of affective, behavioral, and cognitive abilities so that they can mediate the values, beliefs, and behaviors of themselves and others, which will ultimately help them interact with different languages and cultures (Byram, 2006, p. 4).

More recently, Kramsch (2013) explains that there have been two perspectives to understand culture: a modernist view and a post-modernist view. In the modernist perspective and until the 1970s, culture was thought of as part of the literature component of language study. In the 80s and 90s and as a result of the rise of the communicative language approach, culture was associated to the day-today activities and shared experiences of members of speech communities. To Kramsch, speech communities were regarded as preexisting social structures characterized by having common experiences and being grounded in a homogeneous national citizenry (p. 64). For its part, the postmodernist perspective acknowledges the fact that individuals do not share the same goals and values or the same interpretations of events. Meaning and reality are a social semiotic construction that emerges in a non-linear way in interactions with others through discourse transactions. Thus, Kramsch states that culture does not depend on the territory and history. Instead, it results from dynamic discursive processes that individuals constructed and reconstructed when engaged in struggles for symbolic meaning and the control of subjectivities (pp. 68-69). As a result, Kramsch maintains that culture should not be understood simply as behaviors and events, but as possible interpretations that individuals make of practices according to their particular interests and agendas. In other words, culture is the meaning that members of social groups give to the discursive practices they share within a given space and time.

Culture Teaching in Colombia

Different authors have argued for the explicit incorporation of culture into the EFL classroom with the purpose of helping students become familiar with existing cultural differences. Hernández and Samacá (2006) claimed that Colombians are likely to be knowledgeable, tolerant, and respectful since they are members of groups with a high mixture of ethnicities, backgrounds, and genders. If taught explicitly and systematically, argued these authors, learners can develop a sense of respect and tolerance that will help familiarize them with different cultures, discuss them properly, and develop a critical understanding. Ultimately, learners can begin to broaden their mindsets and be more open to diversity and different views of the world.

Cruz (2007) maintained that learning a foreign language is not simply acquiring two linguistic codes, but being aware of the sociocultural, political, and ideological contexts in which the languages function. This awareness can be achieved by working on what is known as both intercultural and multicultural communication. The former takes places between cultures and languages from different countries and is related to cultural shock. The latter occurs between people from different ethnic, social, and gender contexts within the boundaries of the same national language and involves the dialog between minority and dominant cultures. Overall, Cruz encouraged EFL teachers to approach stereotypes, differences in cultural practices, and attitudes toward the target country in order to help students broaden their cultural horizons and explore cultural understanding.

To Álvarez and Bonilla (2009), EFL teaching should no longer center on a linguistic-oriented approach, but needs to focus on achieving a lingocultural experience. Such experience demands an intercultural perspective that integrates otherness (a study of the target culture and its cultural subjects) and myness (a study of who I am as a cultural subject). This perspective presupposes both a critical intercultural approach and an intercultural communication competence. The former has to do with the acknowledgement and acceptance of diversity and the ability to reflect on it analytically; whereas the latter is related to how speakers interact as intercultural subjects in order to create shared meanings. In sum, Álvarez and Bonilla argued that working with cultures should involve a dialogic dynamic between identity and otherness that accounts for the understanding and contact of the target culture and the learner's own culture.

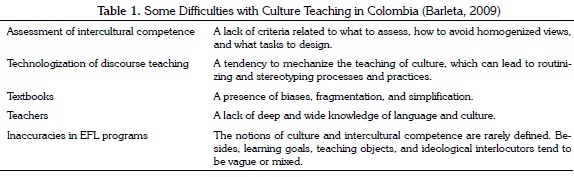

Perhaps more critically, Barletta (2009) drew attention to the fact that foreign language courses are generally associated with tourism or short encounters which do not offer opportunities to challenge ethnocentric attitudes and experience peaceful coexistence. She also pointed out that there is still a widespread structuralist approach to language teaching and a superficial view of culture focused on foods, fairs, folklore, and facts. Together with these limitations, Barletta indicated that most language teachers are not prepared to work effectively with intercultural and multicultural encounters in their classes since their beliefs, methodologies, and discourses lack an enriched perspective from other disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, and semiotics (See table 1 regarding other limitations with culture below). In order to alleviate these weaknesses, she argued for a change of paradigm so that teachers may move from focusing on norms, standards, and regularities (Nbound perspective) towards working with attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors (C-bound approach). Such work needs to affect classroom practices such as discourse and assessment, and transform textbooks, methodologies, and teacher beliefs. More importantly, contended Barletta, the Basic Standards of Foreign Language Competencies in Colombia need to approach the cultural component more adequately in order to better articulate how we wish to represent ourselves, how we want to characterize other cultures, and the types of interactions we want to engage in.

The Question of Culture in Colombia Bilingüe:

From theory to practice

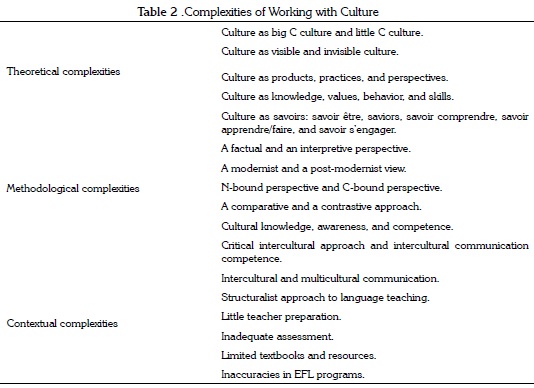

As shown before, working with culture in the EFL classroom is far from easy. Not only is there a myriad of theoretical perspectives related to the definition of culture, but there is also a multiplicity of approaches to teaching it, which can vary according to the needs, interests, and purposes of institutions and participants. Moreover, there is a set of difficulties that constrain why and how teachers and students can approach culture in their classes. Such theoretical, methodological, and contextual complexities make it hard for the program Colombia Bilingüe to adopt and develop consistent and solid discourses. See table 2 regarding such complexities.

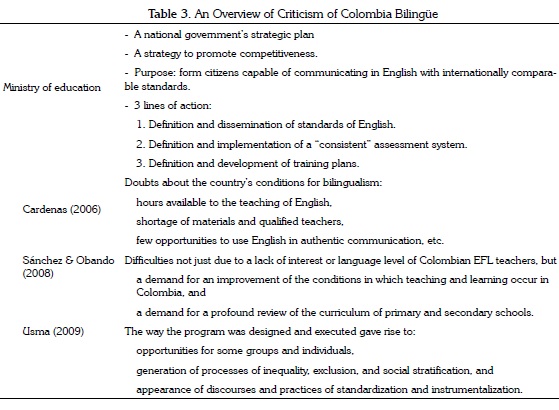

Before discussing how Colombian teachers can approach such a multifaceted concept amid such complexities, it is necessary to consider what Colombia Bilingüe is and how it emerged2. Colombia Bilingüe is a program implemented by the Ministry of National Education not only as the national government's strategic plan for improving the quality of education policy at the basic, intermediate, and advanced levels, but also as a strategy to promote the competitiveness of Colombian citizens. The main objective of this program is to educate citizens who are capable of communicating in English with internationally comparable standards in order to insert the country into universal communication processes (MEN, 2006, p. 6). For its implementation, the program has established three lines of action based on the identification of needs of teachers and students: the definition and dissemination of standards of English, the definition of a solid and consistent assessment system, and the definition and development of training plans.

In regards to Colombia Bilingüe, several Colombian scholars have expressed their concerns. Cardenas (2006) questioned the adequacy of the country's conditions for bilingualism since there are few classroom hours dedicated to the teaching of English, there is a shortage of materials and qualified teachers, classes are numerous and, in general, there are few opportunities to use authentic English communication. Sánchez and Obando (2008), after a profound review of the curriculum of primary and secondary schools, emphasized that the difficulties experienced by this project were not related simply to a lack of interest or language level of Colombian teachers, but with the need for an improvement of the conditions in which teaching and learning occur in Colombia. Furthermore, Usma (2009) argued that Colombia Bilingüe provides opportunities for some groups and individuals, but it mainly generates inequality, exclusion, and social stratification with the new discourses and practices of standardization and instrumentalization that have been adopted. Table 3 presents an overview of criticism of Colombia Bilingüe.

Despite its shortcomings, some authors believe that it is advisable to regard Colombia Bilingüe beyond an imposition of standards and practices of the Common European Framework which overlooks local knowledge and excludes other types of bilingualism. Noticeably, these weaknesses exist within the program, but they are open to debate and improvement. However, after the investments made with public money and the various efforts of the private sector, it is advisable and beneficial to consider the program as a chance for all Colombians to achieve communicative competence in English and other foreign languages. In this regard, Mejia (2011) stated that:

If you can help Colombian students to recognize and accept otherness, and if the National Bilingual Program can help strengthen the value of cultural and linguistic diversity in Colombia, then the disadvantages of many aspects of this policy could be overlooked. (p. 14)

In pursuing this line of thinking, it is worth noting that if the teaching of culture is to be effective and realistic in Colombia Bilingüe, our EFL teaching community must be careful not to let it either become an English sociocultural domination, or take on ethnocentric practices that can lead to isolation. Instead, I am in favor of encouraging Colombian researchers, teacher educators, and EFL practitioners to construct a coherent discourse that allows developing teaching models and learning experiences based on a postmodernist and interpretive perspective. I strongly believe such perspectives may provide both teachers and learners with opportunities to appreciate diversity and recognize awareness and analysis as means of knowledge and communication in today's society. Ultimately, this perspective could help us all question and transform our attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors towards our culture and that of others.

However, it is essential to ask how this perspective can be built into the context of Colombia Bilingüe? To begin with, I think it is important that the EFL community in Colombia acknowledge three important conceptual references that shape today's ELT discourses and practices: the post-method condition, world Englishes, and critical multiculturalism. The post-method condition refers to the contemporary state of affairs in EFL teaching which scrutinizes the previously trusted methods in order to promote the pragmatic and contextual use of a set of approaches and techniques (Arikan, 2006). Kumaravadivelu (1994) maintained that whereas method-based language teaching consists of principles derived from different disciplines and classroom procedures directed at teachers, postmethod-oriented language teaching implies classroom principles and procedures constructed by teachers themselves based on their background and experiential knowledge. In this regard, Khatib and Fat'hi (2012) stated that the shift from the method era to the postmethod condition presupposes a transformation from a view based on transmission and products to a perspective based on construction and processes (p. 23). This shift rejects methods-only arguments in order to value the type of knowledge practitioners possess and to support the informed decisions they make. Ultimately, Khatib and Fat'hi state that the postmethod condition seeks to enable teachers to question their teaching practices, to introduce change in their classes, and to evaluate the results of such variations (p. 24).

On the other hand, regarding English as a global language, Crystal (2003) stated that English has developed a special role worldwide not only because it has been made the official language of several countries, but also because it has been made a priority in different countries' foreign-language teaching. This status has brought about the emergence of new varieties of English which have linguistically and socioculturally challenged the traditional supremacy of British, American, and Australian English. In this regard, Kachru (1992; 2005) introduced the concept of three concentric circles that account for the spread of English. The first, or the inner circle, represents those countries in which English is a native and dominant language. The second, or the outer circle, stands for territories in which English is a second language used in major institutions and multilingual contexts. The last circle, or the expanding circle, corresponds to places in which English is a foreign language used for international communication. Within this context, Jindapitak and Teo (2013) argue that EFL classrooms should equip learners with skills that help them both to perform effectively in linguistic activities and to become effective international speakers, conscious of the diversified contexts of English and respectful of local adaptations and appropriations.

Finally,Kubota (2004) warned the ELT community that a shallow understanding of the variety and diversity of cultural differences and similarities would not dismantle, but keep alive racial and linguistic hierarchies. In other words, the teaching of culture needs to go beyond a superficial celebration of difference and incipient inclusion of diversity in order to critically examine how social and cultural practices are constructed, legitimized, and contested within unequal relations of power. To Georgiou (2010), a critical work with culture involves both placing issues such as race, class, and gender within the larger framework of social struggles and examining how inequality and injustice are produced in relation to power and privilege. As a result, teachers and students should work towards developing the cultural understanding necessary to work with and support speakers from diverse racial, socioeconomic, gender, and language backgrounds.

Conceptual references such as the postmethod condition, world Englishes, and critical multiculturalism invite the EFL community - teachers, students, policy makers, and researchers - to refrain from continuing to treat English as a simple linguistic code or even as a set of competences. Instead, English should be regarded as a global language that people may use to express their local identities and to communicate intelligibly with the world (Crystal, 2006). Similarly, Eaton (2010) states that today's EFL classroom should no longer be focused on grammar, memorization, and rote learning. Rather, it should be reinterpreted as a space to learn to use language and cultural knowledge as a means to connect to others around the globe.

Such change of mind calls for reconceptualized EFL teaching that is more learner-centered and culturally sensitive. This new teaching should focus on helping learners to be capable of engaging actively in the interpretations of the world while comparing and contrasting the shared meanings of both their own and that of others. It should encourage EFL teachers to move away from what Kramsch (1993) called a transmission of information about foreign cultures and their members' worldviews. Instead, this newfangled way of teaching should help them establish a reflective, interpersonal, multifaceted atmosphere aimed at enabling learners' function as mediators between two cultures: theirs and that of others.

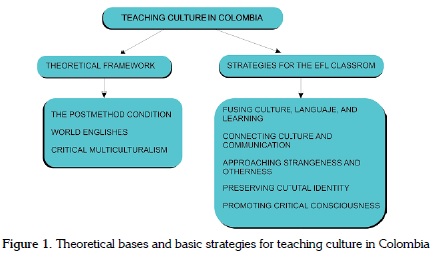

Based on the post-method condition, world Englishes, and critical multiculturalism, I present five practical yet insightful strategies to take into account when working with culture in the EFL classroom. These strategies attempt to be universally comprehensible and easily achievable as to allow for local variation and teacher adaption. Within a framework of reflexivity, sensitivity, and respect, they aim to illuminate institutions, teachers, and researchers so they can pursue linguistic, social, and attitudinal implications of intercultural matters according to the purposes, needs, and interests of Colombia Bilingüe. Ultimately, these strategies seek to help teachers critically examine how to engage learners in experiences designed to prepare them to interact successfully with people with different cultural backgrounds.

Fusing culture, language, and learning in the language classroom

The emphasis in the language classroom should not be that of achieving high levels of proficiency. Instead, learners need to know how to communicate appropriately according to the native language norms while acknowledging their place as members of another culture with a particular cultural frame of reference. In other words, teachers and learners need to reflect upon the different ways that language embodies culture and manifests particular ways of knowing, being, feeling, and doing. Such reflection can be achieved if language learning is infused with activities and resources in which teachers and learners can approach and analyze the beliefs, behaviors, and practices of themselves and of others (Dellit, 2005).

Connecting culture and communication in the language classroom

When working with communication, teachers and learners should not simply emphasize interpreting messages and negotiating meanings. Instead, they should focus on knowing how to interact effectively in cross-cultural situations and to relate appropriately in a variety of cultural contexts (Lázár, Huber-Kriegler, Lussier, Matei, & Peck, 2007). These interactions and relations demand equipping learners with knowledge regarding cultural identity and diversity, attitudes towards establishing and maintaining intercultural dialogs, and skills in favor of flexible behaviors and communication management (Chen & Starosta, 1996). It also requires preparing learners to be both global and local speakers of English so that they feel comfortable in national and international communicative events.

Approaching strangeness and otherness in the language classroom

When working with culture, teachers and learners should be careful not to consider it fixed, stable, and exact information that they can access, memorize, and study. Instead, they should realize that approaching culture means entering into another community's frame of reference and developing social and cultural awareness of why and how the participants of that culture think, feel, and act. The language classroom should encourage learners to move from anxiety and resistance to otherness and strangeness in order for students to embrace comparison and appreciation of similarities and differences. This way, learners may acquire ways of addressing stereotypes and dispelling any prejudices or misconceptions that they may have of other cultures so that they can learn to perceive, accept, and cope with difference and diversity (El-Hussari, 2008).

Preserving cultural identity in the language classroom

When working with culture, teachers and students should avoid seeking to adopt a native-like identity or character. Rather, they should attempt to recognize and validate multiple cultural identities in the classroom community. In other words, there should be opportunities to incorporate and acknowledge the learners' expertise of their language and cultural way of life into the daily fabric of the classroom. In sum, in order to learn to understand and respect others' ways of thinking and acting, one needs to be able to value and reflect on one's beliefs and behaviors (Sumaryono & Ortiz, 2004).

Promoting critical consciousness in the language classroom

When working with culture, teachers and students should refrain from regarding cultures as preexisting structures based on common and overarching values, goals, and memories. Instead, they should be aware of the fact that cultures are neither homogeneous nor static, and that images we hold of other cultures are neither neutral nor objective, but ideologically and discursively constructed. In this regard, Hopkins-Gillispie (2011) maintains that a critical consciousness allows learners to widen their points of view so that they are able to cope with the complex web of intersectional and intercultural relationships of today's world (p. 3). It can, in turn, help learners develop the necessary abilities not just to act in their best interests, but more importantly to participate in the growth of a more unbiased and accepting society (Morgan, 1998, p. 6).

Conclusion

If Colombia Bilingüe or any other similar program want to be successful at working with culture, teachers and learners need to go beyond a superficial celebration of difference and incipient inclusion of diversity so that they can critically examine how social and cultural practices are constructed, legitimated, and contested. They also need to be able to approach and reflect upon their own beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors as well as those of others in order to develop the skills and mindset needed to interact and communicate with people with different cultural backgrounds. Within the theoretical framework of the postmethod condition, world Englishes, and critical multiculturalism, this paper argued that the Colombian EFL community can construct a coherent discourse allowing the development of teaching models and learning experiences aimed at questioning and transforming attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors towards one's own culture and that of others.

In order to start the discussion of such discourse, five strategies were proposed in order to facilitate a better understanding and implementation of culture in Colombian EFL classrooms. These strategies and their theoretical bases (See Figure 1 below) are meant to illuminate teachers and institutions so they can pursue cultural matters critically and favor a reflection of diversity and power as a means of communication in today's world. Ultimately, these strategies can help us all keep away from becoming and creating what Bennett (1993) called "a fluent fool": someone who speaks a foreign language properly, but does not understand the social and philosophical content of that language (p. 16).

Notes

2 For a more profound analysis of "Colombia Bilingüe," readers are advised to read "Retos del Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo: Colombia bilingüe," paper written by Fandiño, Bermúdez, and Lugo in 2012. This paper analyzes the pros and cons of the program in light of its two main challenges: bilingual education for Colombian students and bilingual education for children. As a result, several considerations for teachers of English as foreign language in Colombia are raised in the interest of future developments.References

Agudelo, J. (2009). An Intercultural approach for language teaching: Developing critical Cultural awareness. ÍKALA: Revista de lenguaje y cultura, 12(1), 185-217. Available at http://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/ikala/article/view/2718/2171. [ Links ]

Álvarez, J., & Bonilla, X. (2009). Addressing culture in the EFL classroom: A dialogic proposal. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 11(2), 151-170. Available at http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/viewFile/11448/12099. [ Links ]

Ambady, N. (2011). The mind in the world: Culture and the brain. Observer, 25(5). Retrieved from http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/publications/observer/2011/may-june-11/the-mind-in-the-world-culture-and-the-brain.html. [ Links ]

Arikan, A. (2006). Postmethod condition and its implications for English language teacher education. Journal of Language and Linguistics studies, 2(1), 1-11. Available at http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED495719.pdf. [ Links ]

Barletta, N. (2009). Intercultural competence: Another challenge. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 11(1), 143-158. Available at http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/viewFile/10552/11015. [ Links ]

Bennett, J. M. (1993). Cultural marginality: Identity issues in intercultural training. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience (pp. 109-135). Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press. [ Links ]

Bilash, O. (2011). Culture in the language classroom. Retrieved from http://www2.education.ualberta.ca/staff/olenka.Bilash/best%20of%20bilash/culture.html. [ Links ]

Brown, H. D. (2006). Principles of language learning and teaching. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc. [ Links ]

Byram, M. (2006). Language teaching for intercultural citizenship: The European situation. Paper presented at the NZALT conference, University of Auckland, Australia. Retrieved from http://www.nzalt.org.nz/whitepapers/1.pdf. [ Links ]

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available at http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/source/guide_dimintercult_en.pdf. [ Links ]

Byram, M., & Zarate, G. (1997). Defining and assessing intercultural competence: Some principles and pro-posals for the European context. Language Teaching, 29, 239-243. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. (2006). Bilingual Colombia: Are we ready for it? What is needed? Paper presented at the 19th EA Annual Education Conference, Perth, Australia. Available at http://qa.englishaustralia.com.au/index.cgi?E=hcatfuncs&PT=sl&X=getdoc&Lev1=pub_c07_07&Lev2=c06_carde. [ Links ]

Center for advanced research on language acquisition CARLA. (2011). Culture and language learning: What is culture? Available at http://www.carla.umn.edu/culture/definitions.html. [ Links ]

Chen, G. & Starosta, W. (1996). Intercultural communicative competence: A synthesis. Communication Yearbook, 19, 353- 383. [ Links ]

Clouet, R. (2006). Between one's own culture and the target culture: The language teacher as intercultural mediator. Porta Linguarum: Revista internacional de didáctica de las lenguas extranjeras, 5, 53-62. Available at http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=1709316. [ Links ]

Coombe, R. (1991). Encountering the postmodern: New directions in cultural anthropology. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie, 28(2), 188-205. [ Links ]

Council of Europe. (2001). A common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching and assessment. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe, Language Policy division. [ Links ]

Cruz, F. (2007). Broadening minds: Exploring intercultural understanding in adult EFL learners. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 9, 144-173. Available at http://revistas.udistrital.edu.co/ojs/index.php/calj/article/view/3149/4528. [ Links ]

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language (2nd edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Crystal, D. (2006). English worldwide. In R. Hogg & D. Denison (Eds.), A history of the English language, (420-439). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dellit, J. (2005). Getting started with intercultural language learning: A resource for schools. Melbourne: Asia Education Foundation. [ Links ]

Eaton, S.E. (2010). Global Trends in language learning in the twenty-first century. Calgary: Onate Press. [ Links ]

El-Hussari, I. (2008). Promoting the concept of cultural awareness as a curricular objective in an ESL/EFL: A case study of policy and practice. GLOSSA An ambilingual interdisciplinary journal, 3(2), 441-456. Available at http://bibliotecavirtualut.suagm.edu/Glossa2/Journal/jun2008/Promoting_the_Concept_of_Cultural_Awareness.pdf. [ Links ]

Fandiño, Y., Bermúdez, J., & Lugo, V. (2012). Retos del Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo. Colombia Bilingüe. Educación y educadores, 15(3), 363-382. Available at http://educacionyeducadores.unisabana.edu.co/index.php/eye/article/view/2172/2951. [ Links ]

Georgiou, M. (2010). Intercultural competence in foreign language teaching and learning: Action inquiry in a Cypriot tertiary institution (Doctoral dissertation). University of Nottingham, UK. Available at http://etheses.nottingham.ac.uk/1866/1/Intercultural_competence_in_FLL.pdf. [ Links ]

Halverson, R. J. (1985). Culture and vocabulary acquisition: A proposal. Foreign Language Annals, 18(4), 327-32. [ Links ]

Hernández, O., & Samacá, Y. (2006). A study of EFL students' interpretation of cultural aspects in foreign language learning. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 38-52. Available at http://revistas.udistrital.edu.co/ojs/index.php/calj/article/view/171/278. [ Links ]

Hinkel, E. (2001). Building awareness and practical skills to facilitate cross-cultural communication. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as second or foreign language (3rd edition), (pp. 443-458). USA: Heinle and Heinle. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Ho, S. (2009). Addressing culture in EFL classrooms: The challenge of shifting from a traditional to an intercultural stance. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 6(1), 63-76. Available at http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/archive/v6n12009.htm. [ Links ]

Hopkins-Gillispie, D. (2011). Curriculum & Schooling: Multiculturalism, Critical Multiculturalism and Critical Pedagogy. The South Shore Journal, 4, 1-10. Available at http://www.maailmakool.ee/wp-content/uploads/hopkins-gillispiemulticulturalism.pdf. [ Links ]

Jindapitak, N., & Teo, A. (2013). The emergence of world Englishes: Implications for English language teaching. Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2(2), 190-199. Available at http://www.ajssh.leena-luna.co.jp/AJSSHPDFs/Vol.2(2)/AJSSH2013(2.2-21).pdf. [ Links ]

Johnson, D. (2005). Teaching culture in adult ESL: Pedagogical and ethical considerations. TESL-EJ Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, 9(1), 1-11. [ Links ]

Kachru, B. (1992). The other tongue: English across cultures. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

Kachru, B. (2005). Asian Englishes: Beyond the canon. Hong Kong SAR, China: University of Hong Kong Press. [ Links ]

Khatib, M., & Fat'hi, J. (2012). Postmethod pedagogy and ELT teachers. Journal of Academic and Applied Studies, 2(2), 22- 29. Available at http://www.academians.org/Articles/Feb3.pdf. [ Links ]

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Kramsch, C. (2013). Culture in foreign language teaching. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research. 1(1), 57-78. Available at http://www.urmia.ac.ir/ijltr/Lists/archive_p1/AllItems.aspx. [ Links ]

Kubota, R. (2004). Critical multiculturalism and second language education. In B. Norton & K. Toohey (Eds.), Critical pedagogies and language learning (pp. 30-52). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (1994). The Postmethod condition: Emerging strategies for second/foreign language leaching. TESOL Quarterly, 28(1), 27-48. [ Links ]

Lázár, I., Huber-Kriegler, M., Lussier, D., Matei, G., & Peck, C. (2007). Developing and assessing intercultural communicative competence: A guide for language teachers and teacher educators. Austria: Council of Europe. [ Links ]

Mejía, A. M. (2011). The national bilingual programme in Colombia: Imposition or opportunity? Apples - Journal of Applied Language Studies, 5 (3), 7-17. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional (2006). Formar en lenguas extranjeras: El reto!: Lo que necesitamos saber y saber hacer. Bogotá: Imprenta Nacional. [ Links ]

Morgan, B. (1998). The ESL classroom: Teaching, critical practice, and community development. Toronto: University of Toronto. [ Links ]

Peterson, E., & Coltrane, B. (2003). Culture in second language teaching. (ERIC Digest No. EDO-FL-03-09). Washington, DC: Center for applied linguistics. Available at http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/digest_pdfs/0309peterson.pdf. [ Links ]

Saluveer, E. (2004). Teaching culture in English classes (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia. Available at http://www.lara25.com/mywebdisk/CI-EP/Saluveer.pdf. [ Links ]

Sánchez, A. & Obando, G. (2008). Is Colombia ready for "Bilingualism"? PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 9, 181-195. Available at http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/viewFile/10715/11186. [ Links ]

Sumaryono, K., & Ortiz, F. (2004). Preserving the cultural identity of the English language learner. Voices from the Middle, 11(4), 16-19. Available at http://www.nwp.org/cs/public/download/nwp_file/13982/preserving_cultural_identity_ell.pdf?x-r=pcfile_d. [ Links ]

Taylor, V. (2000). Para/Inquiry: Postmodern religion and culture. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Thanasoulas, D. (2001). The importance of teaching culture in the foreign language classroom. Radical Pedagogy, 3(3). Available at http://www.radicalpedagogy.org/Radical_Pedagogy/The_Importance_of_Teaching_Culture_in_the_Foreign_Language_Classroom.html. [ Links ]

Tomalin, B. (2008). Culture: the fifth language skill. Available at http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/think/articles/culturefifth-language-skill. [ Links ]

Tylor, E. (1871). Primitive culture: Researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Usma, W. (2009). Education and language policy in Colombia: Exploring processes of inclusion, exclusion, and stratification in times of global reform. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 11, 123-141. Available at http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/viewFile/10551/11014. [ Links ]

THE AUTHOR

YAMITH JOSÉ FANDIÑO PARRA, B.A. in English Philology from the National University of Colombia, Specialist in virtual learning environments from Virtual Educa Argentina, and M.A. in Teaching from Universidad de La Salle. Currently, he works at Universidad de La Salle in the School of Education Sciences.