Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

Print version ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.16 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2014

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.1.a09

http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.1.a09

Understanding a reader's attraction to a literary short text1

La atracción de un lector hacia un texto literario corto

Darío Luis Banegas, Ph.D.

University of Warwick

Coventry, Inglaterra

D.Banegas@warwick.ac.uk

Received: 11-Sept-2013 / Accepted: 16-Feb-2014

To cite this article

Banegas, D. L. (2014). Understanding a reader's attraction to a literary short text. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 16(1). 105-113.

Abstract

The aim of this article is to understand why a reader may feel attracted to a short piece of fictional discourse. I analyse a short extract taken from Khaled Hosseini's novel A Thousand Splendid Suns through the integration of different perspectives in discourse analysis. First, I analyse the text in terms of contexts of culture and situation including field, tenor, mode, participants' social world, setting, channel, and key. In the second section, I attempt to examine the text line by line following my interdisciplinary framework of reference. Secondly, I offer a line-by-line analysis through Grice's maxims, topicality, deixis, coding time, types of utterances and verbal processes, and metaphors. Through my analysis, I discovered that my attraction as a reader was based on the combination and integration of different textual devices and my personal interpretation of the pragmatics behind the text.

Key Words: context, discourse analysis, fiction, Hosseini, pragmatics, speech act.

Resumen

El propósito de este artículo es entender mi atracción como lector a una pequeña porción de un texto literario. En esta contribución analizo un extracto tomado de la novela en inglés A Thousand Splendid Suns del escritor Khaled Hosseini. El análisis es llevado a cabo a través de la integración de diferentes perspectivas en el análisis del discurso. Primeramente, analizo el texto en cuanto a los contextos de cultura y de situación, e incluyo campo, tenor, y modo, el universo social de los participantes, tiempo y espacio, canal, y formato. En segundo término, realizo un análisis linear apoyándome en las máximas de Grice, tema, ubicación, tiempo de codificación, tipos de enunciados, procesos verbales, y metáforas. A través de mi análisis concluyo que mi atracción como lector a este pasaje se basa en la combinación e integración de diferentes herramientas textuales y mi interpretación personal de la pragmática que subyace en el texto.

Palabras clave: contexto, análisis del discurso, ficción, Hosseini, acto textual, pragmática.

Introduction

Why does a reader feel attracted to a short paragraph? The purpose of this contribution is to share my attraction to a paragraph from the novel A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini (see Appendix) and how I deconstructed such a paragraph with the aim of understanding what textual devices drive me to perceive it as attractive and self-contained.

A Thousand Splendid Suns was published in 2007. The novel is about two Afghan women, Mariam and Laila, their lived experiences and friendship immersed in an atmosphere of political and social unrest between the 1950s and 1990s. As a reader, I was captivated by the overall story. In particular, I have always returned to an event earlier in the novel because I see it as self-contained and powerful in terms of meaning: a tense moment between Mariam as a child and Nana, her mother, about Mariam's father.

My selected paragraph could be regarded as a text, i.e., a product of discourse (Bloor & Bloor, 2007) since it is meaningful, coherent, cohesive, and incorporates the novel, the larger stretch of discourse from which it comes. The extract condenses the complex relationship between mother and daughter and the latter's father which forms the backbone of the novel. In the analysis which follows, I will explain why this selected paragraph contains the characteristics mentioned above. Even though it is a short piece, it features the textual characteristics of a communicative event (see Paltridge, 2006) and portrays language in use at a fictional level (Cook, 1994; Shawver, 2013).

In the sections that follow, I analyse my selected paragraph from different perspectives to examine why I feel drawn to it.

Different Approaches to Discourse Analysis

As a reader, I became interested in exploring the short text through discourse analysis (DA). DA may be seen as a "heterogeneous discipline" (Mc-Carthy, 1991, p. 7) and a multi-functional tool (Gee, 2011) to study language in use (see Brown & Yule, 1983; Fasold, 1990; Paltridge, 2006) regardless of its text type (Tsiplakou & Floros, 2013). DA is a field which has been strengthened by different traditions (Coulthard, 1985; Jaworski & Coupland,1999) and which continues growing (Gee, 2011). Within those traditions, I will first resort to SFG (Systemic Functional Grammar) because I seek to understand how language is used to generate attractive meaning within me as a reader. According to Halliday and Mathiessen (2004), the ways in which we can use language to construct meaning can be classified into three metafunctions:

- We use language to talk about our experience of the world (ideational metafunction)

- We also use language to interact with other people (interpersonal metafunction)

- We organise our messages in ways which indicate how they fit in with others around them and within the wider spoken or written context (textual metafunction).

Each of these metafunctions is linked to the three components found in the context of situation. According to Bloor and Bloor (2007), the context of situation refers to "the various elements involved in the direct production of meanings in a particular instance of communication" (p. 25). Teubert (2010) notes that meaning does not operate in a vacuum; it needs a context as language comes to be in society. The context of situation of what someone says includes the physical context, the social context, and the mental worlds of the participants (Paltridge, 2006). Following Halliday and Mathiessen (2004), the three components or dimensions (Eggins, 2004) of the context of situation are:

- The field (ideational component) which refers to the topic of the activity and it includes the physical context and who the participants are.

- The tenor (interpersonal component) refers to the relationships of power and solidarity among participants; it also includes the social context.

- The mode (textual component) which refers to how the language is organised and the role it plays.

Such components will aid in the understanding of the context of situation and speech events (see Coulthard, 1985; Paltridge, 2006) because they allow readers to appreciate the totalising landscape a text offers through its interrelated features. Field, tenor, and mode help readers analyse the context in which discourse operates not only at the level of text, but also at the level of interactants and wider universe of discourse enactment.

Following SFG, it becomes essential that cohesion be studied to account for the linguistic tools that the author employs to give texture (Halliday & Mathiessen, 2004) to the fictional dialogue under analysis and the extent to which they impacted my interest for the piece. According to McCarthy (1991) and Taboada (2004), cohesion can be achieved through exophoric and endophoric reference. The former refers to the use of a word or phrase which refers to another word or phrase outside the text. The latter, instead, refers to another word or phrase inside the text. In turn, endophoric reference could be anaphoric (referring backwards to another word) or cataphoric (referring forward to another word).

Although relying foremost on discourse analysis, I also included the following fields in my attempt to discover what supported the text: (1) Pragmatics, through the works of Austin's (1962) types of meaning and speech acts, Grice's (1978) cooperative principle, conversational maxims and implicatures, politeness theory, presuppositions, and deictic reference (see Brown & Yule, 1983, 1987; Davies, 2007; Ishihara & Cohen, 2010; Paltridge, 2006; Thomas, 1995; Vallée, 2008). (2) Conversational analysis, with particular reference in this paper to features such as turn-taking and topic management (Wooffitt, 2005), (3) Ethnography of communication, through the works of Hymes on components of a situation (see Schiffrin, 1994, p. 374), and (4) identities and gender in discourse (see Fasold, 1990; Ndambuki & Janks, 2010).

In order to integrate these views, I resorted to textually oriented discourse analysis (Barker & Galasinsky, 2001) as one dimension of DA (Fairclough, 1999) to illuminate the features of my text (see Bloor & Bloor, 1995) as well as to analyse content (Fairclough, 1999) and context.

It may be argued that, from a theoretical point of view, my interest in analysing a text from an interdisciplinary perspective seems rather ambitious. Yet, I consider that the best way to approach a text should be by resorting to all the linguistic tools available since each will shed light upon a particular feature (Barker & Galasiński, 2001). All of which, eventually, may help a reader understand how words are related and how meaning can be conveyed through different linguistic resources. A reader may find an answer to textual attraction through this type of analysis.

I divide my analysis into two sections. In the first section, I analyse the text in terms of context as knowledge and as situation. In the second section, I attempt to examine the text line by line following my interdisciplinary framework of reference.

Understanding Context

As illustrated in Vertommenn, Vandendaele, and Van Praet (2012), a text can be approached from different perspectives with the aim of understanding how meaning is construed. According to Schiffrin (1994), understanding a text involves understanding its context as knowledge and as situation.

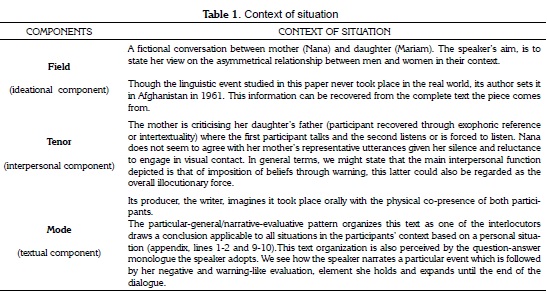

I first explored context as knowledge in the text through the mapping of its context of situation. Table 1 offers a description of the text through field, tenor, and mode.

Context of Situation

However, I realised that this step in my analysis was not enough to understand the context as knowledge. Therefore, I resorted to Gricean pragmatics through the study of implicatures, cooperative principle, and maxims. Maxims of quality, relevance, and manner appear in the text together with semantic presuppositions which contribute to the fact that felicity conditions are created by the writer, and that utterances' presuppositions are mutually known by the participants, Mariam and her mother. Felicity conditions on real speech acts do not necessarily hold for speech acts in literary texts as there is no external truth outside literary discourse and so creation results from maxims being flouted by characters. It is here that I found my first explanation since the context is the product of the writer's imagination. Even when the whole novel is inhabited by real events and real geographical locations, as the reader, I felt attracted by the fuzzy lines between fact and fiction.

I then continued my analysis through Hyme's (see Gee & Handford, 2012; Paltridge, 2006; Thomas, 1995) components of context as situation: the social situation (setting and scene), the participants (their social identities), and the key (speaking style).

As for the social situation and the topicality underpinning my selected text, it could be said that Mariam's mother, the speaker/addressor, speaks about how men act in her world. By this I mean that Mariam's mother first narrates what her father did to her and from there she asserts that men will always put the blame on women. In this process, it should be noted that there is a topic shift, that is, discourse moves from particular, talking about a particular man and a particular woman, to general. The speaker produces a representative speech act referring to a particular man, and then she applies her same utterances and their meaning to all men at the end of the text.

In relation to the setting, I cannot infer information about place and time from the extract itself. Yet, we can imagine the context of culture (see Bloor & Bloor, 2007, p. 27) by the sociology of terms such as "wives" and "Didi." Nevertheless, as a reader of the complete novel, I am familiar with the setting and therefore my interpretation and reconstruction of the scene is richer as I am knowledgeable of the universe created by the author.

Regarding the participants, we may interpret Nana and Mariam by considering their personalities, which seem to be incompatible, their unshared beliefs about the gender issue and the motivations underlying them (see Lam, 2009). The social world of context also encompasses multiple linguistic variables such as social class, ethnicity and race, nationality, linguistic group, religion, kinship, and gender. Through the text, and helped by the complete novel, we know that the participants share kinship since they are mother and daughter; therefore, they also share gender, ethnicity, and linguistic group. Along these lines, I began to perceive how culture acted as an attractive element emerging through these two characters because their culture is different from mine as a Latin American reader.

Culture led me to the key and channel of the event. The key to an event involves the manner in which it is performed (Coulthard, 1985). Through my analysis, I discovered an informal but careful style of speaking (Schiffrin, 1994) since every utterance is intended seriously (Coulthard, 1985). This key tone is also signalled by how the message is constructed together with both participants' gestures (lines 4-5, and 7, see Appendix). Furthermore, this analysis can be expanded by regarding Nana as utterer and her many voices (Verschueren, 1999) given that she is both a source of information and a form of expression (lines 1-2), while Mariam is an interpreter whose silence is as meaningful as Nana's utterances (Ephratt, 2008). This is another feature which I deemed as a source of attraction: Mariam's silence emphasised by her seeming unresponsiveness and initial reluctance to look at her mother. The combination of voice and silence led me to examine the channel.

The channel for this fictional event is both verbal (realised through conversation) and non-verbal (participants' gestures). Nana holds the floor and verbalises her thoughts. In contrast, Mariam remains silent and all we know is that she looked at her mother when she raised her chin with a finger. Nana's utterances show that the code is English, though there is an instance of code-switching in the use of 'Didi?' In addition, this speech event takes the message form of a conversation in which we can identify the speech act of warning. Nana tells her daughter that women are not to be believed in a world dominated my male supremacy and that women will always be accused of anything that may happen in a man-woman relationship.

As regards the message form, we can outline how the concept of face (Birner, 2013; Brown & Levinson, 1987; Thomas, 1995) operates here: I discover how Nana threatens the positive face of the external male participant, Mariam's father, referred to in the event through "he" and "his":

- "You know what he told his wives by way of defence? That I forced myself on him. That it was my fault. Didi? You see? This is what it means to be a woman in this world." (my bold)

All the elements analysed above reveal how culture permeates meaning. Culture helps create meaning in context and therefore one must interpret discourse not only in relation to its context of situation but also to its context of culture. Through my knowledge of culture, I managed to interpret the meaning of "wives," "Didi," and Nana's feelings towards Mariam's father.

Text Analysis from an Interdisciplinary Perspective

I knew that the context of culture was a source of my attraction to the selected text. However, I then sought to analyse the text line by line in order to find other sources emerging from the devices employed by the author.

The text opens with the use of the pronominal form "You," which is the first instance of person deixis which points towards the addressee, Mariam. Then we find after "know," which marks a mental process, the embedded clause "what he told his wives by way of defence?" where "what" holds a cataphoric relation with what is to be uttered next. "what he told" presupposes that this source, who is different from the spokesperson, Nana, who takes an authorial stance by labelling another person's act through "told," said something, a verbal process, to somebody, "his wives." This plural noun helped focus on the context of culture because I placed such an event in communities where polygamy is practised. In turn, "by way of defence?" presupposes an accusation triggered by the item "defence." It presupposes that "his wives" think that "he," their husband and Mariam's father, has done something they consider bad and so they have accused him, therefore he is defending himself. Furthermore, "his wives" presupposes that the speaker, Nana, does not belong to that category. In fact, Mariam is "his" illegitimate daughter. Next, I find two subordinate clauses introduced by "that":

- That I forced myself on him. That it was my fault.

The first clause describes a material process signalled by "forced," which also presupposes that "he" was not a patient; on the contrary, he must have rejected her until he gave in. Regarding these indirect speech instances, their illocutionary force is that of excusing and transferring responsibility. In addition, it can be claimed that Nana shows that "he" broke the Cooperative Principle by flouting the maxim of Quality: do not say what you believe to be false.

In order to signal kinship as well as tenor, the author includes a phrase in Arabic, "Didi?" (item from motherese talk used by parents to call children's attention, it can also mean 'darling'), which in addition reminds us of the participants' linguistic co-presence and cultural setting. This phrase is followed by "You see?" an example of the conceptual metaphor KNOWING IS SEEING (see Kövecses, 2010; Lakoff, 1993) so as to check the addressee's understanding. As regards adjacency pairs, the questions uttered by Nana at the beginning are followed by answers she provides herself. In fact, those questions have the illocutionary force of checking her interlocutor's attention. I also realised that Nana does not use "your father" but "he"; therefore kinship is tacit and at the same time an issue to avoid and hide.

- The next clause describes a relational process by which the speaker points out the evaluation of the event:

This is what it means to be a woman in this world.

It can be seen that this utterance is introduced by a discourse deixis marker, which refers anaphorically to the idea expressed before by the two thatclauses considered above. This utterance, when uncovering its illocutionary force, is an instance of representative utterances performing actions like stating or asserting. Furthermore, I noted that "a woman" plays the role of being inclusive as well as generalising, since what happened to Nana is applied to women in "this world," a space deixis marker which shows deictic centre, that is, the speaker's location, her physical world shared with her interlocutor. I also noticed how coding time (CT), i.e. the moment of utterance, has changed from past in "told," "forced," and "was" to present as indicated by "see," "is," and "means," being this second time the same as time of utterance and receiving time (RT), i.e. when the utterance is received (for more on time deixis and deixis in general see Levinson, 1983). In doing so, not only does the writer cause the speaker to bring the evaluation of a past event to her present time, but also a sense of unity is achieved as the speaker stops.

What follows is a non-verbal event. The following propositions, which show material processes, activate action and act as a transition device for the topic to unfold in the remainder of the text:

- Nana put down the bowl of chicken feed.

She lifted Mariam's chin with a finger.

The lines above show how person deixis has changed from first and second person singular to third person singular. The actor is referred to by her proper name and the pronominal form 'she.' We might also see how space deixis becomes explicit by postures and non-verbal behaviour which signal the proximal co-presence of both participants. In regards to turn-taking, it should be pointed out that our stretch is not characterised by such a feature: while one of the participants, Nana, talks, stops and is about to resume her talk, her addressee/hearer, Mariam, not only remains silent, but also avoids gaze with Nana so as to reject a potential right to speak or be handed over the floor in the system. Conversely, it could be suggested that the speaker seeks to establish mutual gaze as a way of reassuring that the hearer fully understands the illocutionary and perlocutionary forces underlying her utterances: that her mother is right and that she should not trust men, not even her own father.

Nana resumes with an utterance which includes her interlocutor's name for the first time and has the illocutionary force of an order. Regarding the maxim of Relevance, we can say that it triggers the implicature Look at me now:

- "Look at me, Mariam."

Reluctantly, Mariam did.

Mariam unwillingly carries out the perlocutionary force of such a directive utterance. The writer places the adverb 'reluctantly' in front position to emphasise the character's non-verbal behaviour, i.e., how she performs the action of establishing mutual gaze with her speaker, which shows the pragmatic implicature of negation.

Next, the writer introduces Nana's utterances by the use of a verbal process "said," which could be regarded as uninformative without a performative gloss. This choice in wording to present the authorial stance for labelling the speaker's act increases tension since her first utterance is in sharp contrast with "said":

- Nana said, "Learn this now and learn it well, my daughter: Like a compass needle that points north, a man's accusing finger always finds a woman. Always. You remember that, Mariam."

I felt that the attractive power of Nana's first utterance resided in "learn." The repetition of "learn" in a commisive utterance which has the illocutionary force of an order or warning which emphasises the content of what is to follow. This "learn" presupposes that the speaker knows Miriam's ability to do so. Furthermore, this building up of climax is reinforced by the discourse deixis marker "this," which acts as a cataphoric referent of the forthcoming portion of the text, "now," which points CT and deictic centre, and "it," which establishes a cataphoric relation with the rest of the speaker's utterance. These three cohesive markers produce the effect of increasing the reader's expectations as well as maintaining textual coherence and cohesion. In addition, we find an instance of lexical replacement referring to the hearer: Nana first refers to her as "Mariam" (line 6), but it is now that she establishes kinship through the use of "my daughter."

Subsequently, Nana begins her assertion by flouting the maxim of Manner through another source of attraction to me as a reader. She uses a figure of speech, a simile, to convey meaning:

- Like a compass needle that points north

However, she cancels ambiguity by explicating the analogy through the use of metonymy and metaphor:

a man's accusing finger always finds a woman

I noted the metonymic use of "finger," a part for the whole, which refers back to "needle," thus completing the intended sentential metaphor. This "a man" is intended as an inclusive device which aims at reaching the entity pronominalised by "he" in the text together with all men. On the other hand, the word "accusing" presupposes that these men to whom the speaker refers think that a woman's actions, whatever they are, are always bad. What is more, the verb "finds" also presupposes searching: men look for women to be blamed for whatever happens in a given situation since the latter are always found guilty. This metaphorical chunk, "man's accusing finger" in particular, recaptures the speaker's utterances in lines 1-2, thus, the overall illocutionary force intended in this fictional dialogue comes full circle.

Last, the repetition of the adverb "always" triggers the scaler quantity implicature of truth. It is not the speaker's opinion; it is an assertion, nothing but the truth, what the speaker utters. In addition, the presence of "always" shows that no mitigators or hedges are used; on the contrary, statements are absolute and demonstrate confidence to such an extent that we find the use of "always" as a booster two times in the text.

The piece finishes with a directive utterance which is materialised through warning carrying the perlocutionary act of persuading and frightening. The mental process "remember" together with the anaphoric use of "that" recover the preceding metaphor so as to emphasise the force of what has been said.

Conclusion

In sum, my analysis of the textual devices employed by the author and my interdisciplinary framework helped me realise that my attraction towards this small stretch of literary discourse resided in: (1) the context of culture created by the writer and developed in the complete work and the use of words such as "wives" and "Didi," (2) the topic shift from Nana's experience to her warning about all men, (3) the change in coding time illustrated through this topic shift, (4) the tension created between Nana's utterances and Mariam's silence and non-verbal activity, (5) the inclusion of Mariam's father through "he," (6) the illocutionary forces underpinning Nana's utterances, and (7) the metaphor Nana inserts to illustrate her claim about how men behave in their world.

As a reader, I found the answer to my initial question: Why does a reader feel attracted to a short paragraph? The reasons numbered above became a source of attraction not in isolation but through their interaction and proximity in a short literary text. Furthermore, attraction was based on my personal interpretation of those devices, i.e. the meaning I assigned to them in the relationship between the reader and the text (see Lecercle, 1999).

In addition, I also discovered that a short text can become a rich territory to explore how meaning is constructed aided by different theories and traditions.

References

Austin, J.L. (1962). How to do things with words. Oxford: Clarendon House. [ Links ]

Barker, C., & Galasiński, D. (2001). Cultural studies and discourse analysis. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Birner, B.J. (2013). Introduction to pragmatics. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Bloor, M., & Bloor, T. (1995). The functional analysis of English. London: Arnold. [ Links ]

Bloor, M., & Bloor, T. (2007). The practice of critical discourse analysis. An Introduction. London: Hodder Arnold. [ Links ]

Brown, G., & Yule, G. (1983). Discourse analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. In A. Jaworski & N. Coupland (Eds.). (1999), The discourse reader (pp. 321-335). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cook, G. (1994). Discourse and literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Coulthard, M. (1985). An introduction to discourse analysis. Essex: Longman. [ Links ]

Davies, B. L. (2007). Grice's cooperative principle: Meaning and rationality. Journal of Pragmatics, 39, 2308-2331. [ Links ]

Eggins, S. (2004). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics (2nd edition). London/New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Ephratt, M. (2008). The functions of silence. Journal of Pragmatics, 40, 1909-1938. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (1999). Linguistic and intertextual analysis within discourse analysis. In A. Jaworski & N. Coupland (Eds.), The discourse reader (pp. 183-211). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fasold, R. (1990). Sociolinguistics of language. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Gee, J.P. (2011). How to do discourse analysis: A toolkit. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gee, J.P., & Handford, M. (Eds.). (2012). The Routledge handbook of discourse analysis. Abingdon/New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Grice, H.P. (1978). Further notes on logic and conversation. In P. Cole (Ed.), Syntax and semantics 9: Pragmatics (pp. 113-128). New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Halliday, M., & Mathiessen, C. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (4th edition). London: Arnold. [ Links ]

Hyland, K. (2005). Metadiscourse. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Ishihara, N., & Cohen, A.D. (2010). Teaching and learning pragmatics: Where language and culture meet. Harlow: Pearson. [ Links ]

Jaworski, A., & Coupland, N. (Eds.). (1999). The discourse reader. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kövecses, Z. (2010). Metaphor: A practical introduction (2nd edition). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (2nd edition, pp. 202-251). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Lam, M. (2009). The politics of fiction: A response to new orientalism in type. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 4, 257-262. [ Links ]

Lecercle, J-J. (1999). Interpretation as pragmatics. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Levinson, S. (1983). Pragmatics. London: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

McCarthy, M. (1991). Discourse analysis for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ndambuki, J., & Janks, H. (2010). Political discourse, women's voices: Mismatches in representation. Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis across Disciplines, 4, 73-92. [ Links ]

Paltridge, B. (2006). Discourse analysis: An introduction. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Schiffrin, D. (1994). Approaches to discourse. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Shawver, B. (2013). The language of fiction: A writer's stylebook. Lebanon: UPNE. [ Links ]

Taboada, M.T. (2004). Building coherence and cohesion: Task-oriented dialogue in English and Spanish. Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Teubert, W. (2010). Meaning, discourse, and society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Thomas, J. (1995). Meaning in interaction: An introduction to pragmatics. Essex: Longman. [ Links ]

Tsiplakou, S., & Floros, G. (2013). Never mind the text types, here's textual force: Towards a pragmatic reconceptualization of text type. Journal of Pragmatics, 45, 119-130. [ Links ]

Vallée, R. (2008). Conventional implicature revisited. Journal of Pragmatics, 40, 407-430. [ Links ]

Verschueren. J. (1999). Understanding pragmatics. London: Arnold. [ Links ]

Vertommen, B., Vandendaele, A., & Van Praet, E. (2012). Towards a multidimensional approach to journalistic stance. Analyzing foreign media coverage of Belgium. Discourse, Context & Media, 1, 123-134. [ Links ]

Woofitt, R. (2005). Conversation analysis and discourse analysis: A comparative and critical introduction. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Appendix

CORPUS

- "You know what he told his wives by way of defence? That I

- forced myself on him. That it was my fault. Didi? You see?

- This is what it means to be a woman in this world."

- Nana put down the bowl of chicken feed. She lifted

- Mariam's chin with a finger.

- "Look at me, Mariam."

- Reluctantly, Mariam did.

- Nana said, "Learn this now and learn it well, my daughter:

- Like a compass needle that points north, a man's accusing

- finger always finds a woman. Always. You remember that,

- Mariam."

Source: Hosseini, Khaled (2007). A Thousand Splendid Suns. New York: Riverhead Books. pp 6-7.

THE AUTHORS

DARÍO LUIS BANEGAS is Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics, teacher educator and curriculum developer at the Ministry of Education of Chubut (Argentina), president of APIZALS and founding editor of AJAL.