Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

Print version ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.16 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2014

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.2.a02

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.2.a02

Research Article

Towards implementing CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) at CBS (Tunja, Colombia)

Hacia la implementación de contenido y aprendizaje integrado de lengua en CBS (Tunja, Colombia)

Claudia Marina Mariño Ávila, M.A.1

1 VIF. Jacksonville, United States. clauditacmma@gmail.com

Citation / Para citar este artículo: Mariño, C. M. (2014). Towards implementing CLIL at CBS (Tunja, Colombia). Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 16(2), 151-160

Received: 10-Jul-2013 / Accepted: 09-May-2014

Abstract

Lately, the use of CLIL in classrooms has been expanding due to the interest in educating bilingual children. In Colombia, this approach is becoming known and is being applied in many schools, mainly bilingual. This article presents a case study that sought to investigate how some of the characteristics of a content-based English class can be taken into account to implement CLIL at CBS to contribute to the education offered to these students. The study was supported by the latest theoretical constructs of CLIL from representative authors such as Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010), among others. The data consisted of six videotaped classes from fifth grade, a class observation form, a student questionnaire, an informal interview, a teacher's journal, and other documents such as the teacher's lesson plans. The results were qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed using Seliger and Shohamy (1990) techniques. The study revealed that the observed classes met several positive standards that can be used when implementing CLIL at the school such as language methodology and assessment. It was also found that specific CLIL characteristics such as the 4Cs and the language components need to be widely understood and worked by teachers and students before implementing CLIL at the school.

Keywords: Additional language, bilingual education, Content Language Integrated Learning, teaching through content, Language of, for and through learning, 4Cs, CLIL matrix, Assessment in CLIL.

Resumen

Últimamente el uso de CLIL en los salones de clase se ha incrementado debido al interés en educar niños bilingües alrededor del mundo. En Colombia, esta metodología se ha vuelto popular y está siendo usada en varios colegios, principalmente bilingües. El presente artículo explica el desarrollo de un Estudio de Caso adelantado con el fin de investigar cómo se usa CLIL en el colegio CBS para contribuir con la educación bilingüe ofrecida a los estudiantes. El estudio se construyó teniendo en cuenta las últimas teorías sobre CLIL desarrolladas por autores importantes, como Coyle, Hood y Marsh (2010) entre otros. Los datos se recolectaron utilizando videos, un formato de observación, un cuestionario para los estudiantes y un diario que llevaba el profesor. Los resultados se analizaron cualitativa y cuantitativamente utilizando las técnicas de Seliger and Shohamy (1990). Los resultaron revelaron que las clases observadas cumplen con la mayoría de los estándares de una clase de Inglés en términos metodológicos de la enseñanza y de evaluación de un idioma extranjero. De igual manera, se encontró que las 4C's y los componentes del lenguaje deben ser entendidos y trabajados por los docentes antes de implementar CLIL en los colegios.

Palabras clave: Aprendizaje integrado de contenido e idioma, lenguaje adicional, enseñanza a través de contenido, educación bilingüe, idioma de, para y a través de aprendizaje; 4Cs (Contenido, Comunicación, Cognición y Cultura), Matiz de CLIL, Evaluación en CLIL.

Recently, the globalization process and technological advances have motivated the use of a global network of communication in which the mastery of different languages is mandatory. This fact presents many challenges for education, such as educating students in one or more foreign languages. This educational need has led many countries around the world to promote educational systems in which students are educated in at least one foreign language. Hence, bilingual schools appear as a successful tool to achieve such an educational objective.

In Colombia, bilingualism continues to be one of the most controversial topics when referring to foreign language. Furthermore, because bilingualism has a many definitions, each bilingual institution has a different approach to educate bilingual students; hence, this issue becomes even more controversial and in a certain way, difficult to manage.

The need to learn English in Colombia has transformed bilingual education into the first option for learning English. This bilingual process began when the Ministry of Education (MEN) - through the Educational Polices (law 115 from 1994) - established the Colombian Bilingual Project (2004-2019) following the Common European Framework policies. Therefore, some public and private schools integrated content and language teaching areas such as math or science in English as a strategy to become bilingual.

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) appears as a suitable option in this dilemma in how to educate bilingual students because it is a dual-focused educational approach in which an additional language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language. (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh. (2010), p.1)

Bearing in mind the different contributions that CLIL may offer to our educational system, the present article presents a research study that sought to analyze how some of the characteristics of a content-based English class can be taken into account to implement CLIL at CBS by examining the teaching-learning process. The study and its objectives were carried out in order to contribute to the development of CLIL in Colombia, and hence, participate in the objective of meeting the standards of good bilingual education in Colombia. In addition, sub-questions, such as the following were taken into account to develop the research: "What characteristics of a content based English lesson are found in Country Bilingual School classes?", "How Content, Culture, Cognition and Communication are addressed in the teaching-learning processes at Country Bilingual School?, "How is English taught at Country Bilingual School?, "What characteristics of a CLIL lesson are found in Country Bilingual School classes?".

Literature Review

According to Delgado (1998), learning a foreign language improves children's cognitive development and helps structure children's personality. In addition, bilingual children use effective strategies when learning and communicating. Bilingualism is positively related to aspects such as building creativity, conservation tasks (Piaget & Inhelder, 1973), logical thinking, and classification abilities. Thus, bilingual people develop these abilities and use them not only in linguistic learning, but also in some other knowledge fields like math, social studies, or literature.

In order to respond to the need of educating bilingual students, different models of instruction have been created. In The United States, for example, an approach called Sheltered Instruction was developed by Echevarría, Vogt, and Short for helping immigrant students achieve high academic standards. Echevarria, Short and Powers (2006) report that more than 90% percent of immigrants that had arrived to the United States came from non- English speaking countries. This fact has contributed to the significant population of non-native English speakers with ethnically and linguistically diversity but with limited skills in English.

Defining CLIL

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is an overarching term covering a wide range of educational approaches from immersion, bilingual education, or language showers, to enriched language programmes (Yassin, Tek, Alimon, Baharon, & Ying., 2010). Similarly, if it is true that the notion of CLIL seems to be diverse and have many faces (Mehisto, Marsh, Frigols, 2008), "it has a converging feature of a double-barrel approach in which the content of a non-language subject is fully, largely or partially taught through a second or foreign language" (Yassin, et al., 2010, p. 47). This is to say that both content and learning are viewed with the same importance during the teaching-learning process, and they both interconnect at different stages of the learning process, if not during the whole learning process itself. CLIL is content-based which helps develop the experience of learning a language to a deeper extent.

Curricular Conditions for the Use of CLIL

Marsh, Maljers, and Hartiala (2001) explain that there are different reasons to implement CLIL in schools because it offers a lot of benefits to educational institutions. All of the reasons the authors state are given in terms of context, content, language, learning, and culture. In relation to context, the authors state that implementing CLIL is a way to prepare for globalization. They also suggest that it may help schools access international certification as well as to increase school profiles. Regarding content, CLIL prepares students for future studies and offers them a different point of view of sciences. Additionally, students in CLIL programs have real access to specific information within different knowledge areas and they can gain abilities which will help them better perform in their jobs.

There are many reasons for introducing CLIL concerning language. Students learning in a CLIL program acquire self-confidence and are introduced to the learning and usage of another language. Furthermore, CLIL students improve their competences in the target language and develop oral communication skills while gaining awareness of mother tongue and vehicular language. CLIL also improves students' motivation and helps learners develop learning strategies. Moreover, while learning via CLIL, students develop their understanding and tolerance to culturally different people (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010).

CLIL Theoretical Constructs

Content in CLIL may be as flexible as each context requires it to be and may be implemented in a classroom in different ways. It can be developed through theme-based activities, units or projects, or by cross-curricular studies involving different contents of the school curriculum, providing students with opportunities to heighten learning and to acquire skills and development.

Even if learning through content has a lot of benefits in terms of education, learners need to be cognitively engaged for effective learning to take place. Hence, teachers must contribute to this process by helping students develop their learning and metacognitive skills. Similarly, teachers may be able to provide students with the abilities they need to use the knowledge they have acquired in real life by means of creative thinking, problem solving, and cognitive challenge.

Bearing in mind that CLIL learners are expected to advance consistently in both content learning and language learning and use, Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) suggest using the Language Triptych for strategically sequencing and interrelating language and content objectives. The Language Triptych is a representation that integrates language use from three perspectives: language of learning, language for learning, and language through learning.

Language of learning refers to the analysis of the language students may need to attain key concepts and abilities related to a theme or topic worked in the classroom. Language for learning concerns the type of language students may need to perform in a language environment and how they are going to use the language. Language through learning refers to the active involvement of language and thinking in the learning process.

Culture is also one of the main aspects to be worked in the classroom. CLIL is an instrument to lead students towards an intercultural world where they can have contact with different languages, different people, and thus, different living experiences. As Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) state, culture awareness may be addressed by interaction with people from different contexts in the classroom or in other settings by means of different instruments such as the web.

The 4Cs Framework

A curricular model that integrates the 4 main components in CLIL: Communication, Content, Culture, and Cognition, was recently adapted by Zydatiß (2007). The author creates a non-hierarchical model in which there is interdependence among all the areas, but communication is placed in the center of the model.

Subsequently, Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) confirm this model pointing out that the framework is "built on the premise that quality CLIL is dependent on understanding and operationalizing approaches which will not be found solely in the traditional repertoires of either language teaching or subject teaching" (p. 549). The authors suggest that a unit based on CLIL must be constructed under the theory of the 4Cs and under other CLIL principles. They explain each of the Cs as follows:

CONTENT: Content in CLIL refers to the thematic learning students are expected to acquire. It is very useful for teachers to think of content in terms of knowledge, skills, and understanding because this idea will guarantee deeper learning.

COMMUNICATION: Students learning under the CLIL model learn by using the language instead of by learning it (which usually refers to the learning of grammar). CLIL integrates content and learning in such ways that both are very important and complement each other in the learning process. In addition, students are usually involved in situations that allow them to interact.

COGNITION: CLIL students are usually involved in activities that allow them to construct new understandings by using higher thinking and by learning under a determined taxonomy. They are usually developing their cognitive processes and acquiring knowledge at the same time (content and language integration). Moreover, students are always being challenged to develop new skills that they can use in many daily-life situations.

CULTURE: when working with CLIL, students are expected to develop a deep understanding of the "other" and of "self." Students participate in activities that help them understand similarities and differences between cultures by using authentic materials, reading about other countries, and by linking curricula. CLIL teachers may extend the content to different contexts and cultures, guiding students towards more pluricultural knowledge.

Planning CLIL lessons, units, and programs

Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) developed a six-stage process, whose purpose is to give teachers a tool for planning and developing their own CLIL model. They suggest that teachers begin the process by having in mind that the CLIL model is flexible and accordingly can be adapted for all contexts.

The first stage in the process of planning CLIL is to come up with a common idea of CLIL.

After teachers have agreed on the idea they have and want to project about CLIL, they may go to the next stage in which they will analyze and personalize the CLIL context. Then, teachers are ready to begin the third stage of the process: planning a CLIL unit. A unit based on CLIL must be constructed under the theory of the 4Cs and under other CLIL principles. Once teachers have planned their CLIL units, they may move on to the next stage: preparing the unit. At the fifth stage, teachers monitor, evaluate, and understand CLIL in the classroom, and they use the gathered data to plan future units. The last stage for planning a CLIL program is to think of inquiry-based professional learning communities.

Assessment in CLIL

Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) suggest that CLIL teachers guide the assessment process in their contexts by being specific on issues such as how they define assessment in CLIL, if they want to assess language or content, why and how they will do it, how they are going to include cognition and culture in the assessment process, and who and when to assess.

In order to talk about assessment in CLIL, it is necessary to establish clear learning objectives, to use a mixture of formal and informal assessment, to familiarize the students with the assessment criteria, to assess content knowledge using simple language, to assess language for a real purpose in a real context, and to design assessment methods appropriate and coherent to the level of students, both in content and language. In addition, it is important to let students know what they are expected to learn, how they are going to be assessed, and the work they must do and when they should complete it. Thus, students are able to assume a responsibility for their own assessment. Similarly, assessment must be done at different stages: before, during and after lessons, units and courses, and when students need extra help in their learning process.

State of the Art

For the purpose of the study, an analysis of research in CLIL in a number of countries of the world was addressed. It is necessary to point out that, although a very careful bibliographic search on CLIL studies around the world was done, very little was found on the specific issue to be studied (CLIL in Elementary schools). For this reason, studies on different CLIL aspects were taken into account.

One of the countries that has conducted some research on CLIL in Europe is the Netherlands. De Graaff, Koopman, and Weshoff (2007) carried out a research which was developed with the main objective of observing and analyzing effective CLIL teaching performance facilitating language development and proficiency. The conclusion of the study was that the CLIL lessons showed instances of effective language teaching performance; that is to say, teachers are effective practitioners in terms of second language pedagogy.

Spain has also developed a lot of research on CLIL. Llinares and Whittaker (2006) aimed to analyze students' oral and written production of CLIL in secondary schools, by finding out "the linguistic needs at different points in the process of schooling in a specific discipline" and "the language used by students, as well as that of the teachers and textbook material." (Llinares & Whittaker, 2006, p.28)

Italy is another country that reports a lot of research on CLIL. Ting (2007) aimed to analyze the perceptions of CLIL students and their foreign language and science content learning process. He found out that students, after working in classes under the methodology of CLIL, built a very good speaking competence which was demonstrated while giving oral presentations about topics such as the human body or physics before a professors' audience.

Among many other research studies, the most similar to the study reported in this article and

therefore, the most important, was carried out in Austria. Buchholz (2007) aimed to find out if CLIL was implemented in the primary school English classes and to what extent CLIL was implemented in primary school teaching. This study constituted a valuable reference for the investigation because it was also carried out in elementary, because it took into account the teachers, and because it suggests teacher training as an important tool for improving the use of CLIL at Elementary schools.

It is also essential to review some of the research on CLIL that has been carried out in Latin America because they relate closely to our context. However, very little information regarding CLIL in Colombia was found in the bibliographic search. Just two research studies were found, they were carried out in this country, and they were both done at university level.

One of these studies is called "Strategies for Teaching Geography Electives in English to Native Spanish Speakers at a Colombian University." It was done by Nohora Bryan and Ezana Habte-Gabr (2008), with the main objective of "testing instructional strategies leading to improve English content-based courses or CLIL results at Universidad de la Sabana in Colombia" (Bryan & Habte-Gabr, 2008, p. 2). The researchers concluded their study by pointing out that students may improve their content and language knowledge by using certain pedagogical strategies, such as using the internet, carrying out projects and having guest speakers. Moreover, they suggest that it is very profitable for students to maintain a close relation between the content and the language teachers and departments. Finally, they recommend that teachers use the methodology suggested as a way to improve students' knowledge and performances.

It is important to point out that, as seen in the collection of research studies made, very little research has been carried out in Colombia, specifically in Elementary levels; thus, the study became very relevant in this context.

Research Design

Setting

The research took place at CBS in Tunja. CBS is a private school founded five years ago with the main objective of educating bilingual students. The school has a strong emphasis on English in high school levels and it claims to be bilingual at the elementary level. In elementary school, some subjects such as science, math, social studies and religion have been taught in English since 2008. Regarding human resources, the school staff and teachers are Colombian. Some of the teachers who work there are pre-school teachers who have been abroad for one or two years, some others are English teachers, and others are high school teachers graduated from programs such as mathematics or sciences who do not speak English and teach in Spanish.

Participants

The participants to work with were 15 students in fifth grade and there was only one fifth grade in the school. Children were between eleven and twelve years old. Most of the students belong to an upper social class, which explains why their parents are interested in educating their children in a foreign language. Students attend eight hours of class daily.

Data Collection Instruments

Five instruments were used to gather and analyze the data in the study. An observation form, a journal kept by the teacher, a survey for the participants, an interview with the coordinator of the school, and documents such as the teacher's lesson plan book were also analyzed during the investigation.

Data Analysis Procedure

Two different techniques were followed to analyze the gathered data following Seliger and Shohamy's (1990) foundations on analyzing.

qualitative research data. A first technique in which the "categories derived from the data" (Seliger & Shohamy, 1990, p. 208), and a second technique in which the data should be approached "with predetermined categories" (Seliger & Shohamy, 1990, p. 205) that were obtained from the conceptual framework of CLIL.

From the data, two types of categories were established. The first ones were categories that emerged from the data; categories that focus on the explanation of the lesson as a content-based English class, such as: assessment, previous knowledge, code-switching, non-verbal communication, and pedagogy and discipline. The second ones were categories that were established bearing in mind the theory of the 4Cs in CLIL to determine what the observed classes did and did not have of CLIL. The 4Cs in CLIL are: content, communication, cognition and culture. Consequently, three main categories were set, also named communication, cognition and culture. The other C: Content was always immersed in the observed classes and was leading the development of the other Cs in the classes. Then, it is taken as a more general aspect during the data analysis.

Triangulation was also used to analyze the information obtained from each of the instruments used in the investigation because triangulation, the combination of two or more data sources, benefits the research in terms of the nature and number of data generated for interpretation.

Findings

In order to find the answer to the research question, the data was analyzed and the categories that directly emerged from the information gathered were established. Aspects such as assessment, previous knowledge, code-switching, non-verbal communication, and pedagogy and discipline were also analyzed.

Assessment, as in every teaching process, also took place in the observed classes. Assessment is a very important aspect in CLIL because it allows the teachers to have a complete picture of their work as well as their students' work to plan future classes and to make decisions. The assessment process observed in this investigation was neither completely developed by the teacher nor by students.

The only kind of language as well as content assessment found in the observed classes occurred when students were giving oral presentations or when they were participating in games or similar class activities. This may mean that all the assessment process the teacher did was based on the students' oral production and that the teacher was neither clear about the criteria for assessing her students nor about the reasons to evaluate their language level. The excerpts below exemplify these assumptions:

T: Ok. Do you know any animals that live in tundra?

S8: Tundra live the bear grizzly…grizzly bear

(June 3rd, 2010)

S8: and warm

T: and what about the rain?

S2: lluvia, it's very rainy

T: and what about the trees? How are the trees there?

S8: uy thousands

T: thousands of trees very good, tall, small?

S2: tall, medianos

T: medium size, good.

(June 3rd, 2010)

Regarding language assessment in these classes, it can be inferred from the corrections the teacher made to her students that she was assessing her learners' language management spontaneously as they made grammar, pronunciation, or vocabulary mistakes, as can be seen in the excerpts shown below. Hence, the teacher was neither clear about the criteria for assessing her students nor about the reasons to evaluate their language level.

T: and deciduous forest, Thank you Luisa… deciduous forest, one characteristic of deciduous forest quickly

S3: has people?

T: most of the ecosystems HAVE people, there are people in there

(June 3rd, 2010)

In addition to assessment, other processes took place in the observed classes. Strategies for communicating, such as code-switching and non-verbal communication as well as the way students use their previous knowledge or situations related to the pedagogy and the methodology of the classes were also considered in order to make a complete analysis of the gathered data.

Code-switching and translation took place in the classroom as strategies the students used to overcome communication and understanding problems. When one student, for example, tried to explain something and did not find the word in English, s/he said the corresponding word in Spanish, so s/he could continue talking and saying what s/he meant. In the same way, when one student did not understand what the teacher said, s/he asked for translation to the classmates, and after getting the required word in the mother tongue, s/he showed understanding. Excerpts such as the one below support these facts:

T: Ok, deserts, one characteristic of deserts, quickly!

S7: in desert are more harder

T: hotter

S7: are more hot

T: yes, are hotter

S7: and are poquitas, ¿cómo se dice poquitas?

S7: few plants

T: and there are few plants, good.

(June 3rd, 2010)

Non-verbal communication was also present in the observed classes. It was used not only by the learners, but also by the teacher in order to facilitate understanding. The Teacher produced gestures and signs when she needed to explain a new word or when her students did not understand what she was saying. Students nodded their head or used other non-verbal communication signs when they needed to say something but did not find the words in English.

Something interesting about the observed classes was the teacher-student rapport. The students and the teacher seemed to be comfortable in class, apart from the moments when children misbehaved. This environment allowed humor to take place in the classroom. Students with an advanced level of English made some jokes in the target language about their classmates or about curious situations that happened in the classroom. In addition, the teacher also laughed because of the funny students' sayings, ideas, and actions. Kids seemed to have a good sense of humor and the teacher allowed them to show this aspect of their personality in her classes. The excerpt below exemplifies a humorous situation

T: So, what day is today?

Sts: Twoo

T: two what?

S5: June two

T: June SECOND

S3: July, July … (To a student

named Julio) Is your brother that June?

(June 3rd, 2010)

It was also observed that students used their previous knowledge in order to perform well in some tasks assigned by the teacher. Students always used their previous knowledge in classes so they would be able to construct new knowledge in a more effective way. In addition, because students seemed to be linking the new knowledge with the concepts they already knew, and the new understanding with the previous experiences they lived, we may dare to say meaningful learning was taking part in the observed classes.

Some other important aspects about pedagogy and methodology were found in the classes. All of the aspects about the way a teacher carries out a class, the activities, materials, and strategies s/he likes to use, the decisions s/he makes taking into account what is really happening in the classroom, the way s/ he manages the classroom and her/his feelings and beliefs seem to be important issues that need to be taken into account when applying a new methodology in class, or even when that methodology is first being introduced in a classroom or a school. The following teacher journal entries support these findings:

"Sometimes I think my students understand what I haven't said, because I assume it is obvious for them, when it is not. I could noticed that when I asked my students to place some decimal numbers in the Place Value Chart. One of them was placing 13 in the same column when he should place 1 and 3 in different columns, but I never told them to do so, hence, the mistake in this learning process was mine, not my students'. And even with that mistake in my class, there were some kids that understood how to place the decimals in the Chart, what proves that students really learn despite their teachersL." (Teacher's Math Journal, p. 5. June 2nd, 2010)

"Now that I reflect on my class, I can say that my answers were not the best; my students need further and more detailed explanation. I said something short and thought they would get it, but I would say they didn't." (Teacher's Math Journal, p. 3. June 2nd, 2010)

The first predetermined category, communication, refers to all the interaction events that took place in the classroom. Likewise, it concerns the progression that students showed in terms of language usage and learning. This is the reason why this category is divided in two sub-categories: language and interaction. Language for CLIL is "a conduit for communication and for learning which can be described as learning to use the language and using the language to learn" (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010, p.54). Hence, an analysis about all the aspects that have to do with the way in which language features are present in the classes and how language is being used by the teacher and the students in the classroom is done.

According to the excerpt below, it is possible to observe that students were using the target language a lot; the observation format suggests this happens most of the times in science classes. They talked among themselves and to the teacher using the language they know. Something valuable about students' talking in English is that they use the vehicular language in both academic and communicative situations. They are able to express their feelings or needs, and they can also talk about an academic topic, such as an ecosystem:

S8: ¿Quién escribe?

S3: Ok. I will write, because you don't want

S9: Yes, I want!

S3: Ok, so, just do it!

S9: But we need the line!S3: Grass lands. The few trees found in grass lands are along rivers and streams, eeeh, the temperature is rain fall, the rain fall lies the grasses …

Grass lands are used to livestock such as carrots and chips.

Grasslands are found in all the continents specially America.

Live more animals such as rabbits, dogs, tigers----- and insects live in grasslands.

Grasslands produce so much food that they are sometimes called the break basket of the world.

(June 3rd , 2010)

The constant use of the target language in science and math classes seems to prove that the philosophy the school has about English classes as the "input" students may receive for being able to produce and interact in science and math is

really working as they expect. As the coordinator of the school pointed out, they see English classes as the right moment to give students the tools they may need when performing in the other classes: "English classes are the input students need to handle the other subjects… They learn how to write, to read and to speak… Children need to be exposed to the language for them to learn English…"

During the interview with the coordinator, he also stated that the mission of CBS was to provide students with processes that could help them to interact and to have more real experiences with the language. There seems to be a connection between this objective and what really happens in the classroom because all the instruments used to gather data clearly demonstrate many situations where students interacted. In fact, there was interaction between the teacher and the students and also among the students.

Children talked among themselves when they were working in groups. They tried to speak English as much as possible, they helped each other when needed, and they even tried to invite each other to speak in English. The students' English level clearly had to do with the types of interaction existing among them. We observed conversations that were "transparent" in terms of language and meaning, but others that showed some problems in terms of understanding due to the lack of language ability.

Taking into account all the events, situations, and aspects about communication found in the observed classes, it can be said that there is a need of improving the language component so that it matches the requirements a CLIL class may have in terms of Language of learning, for learning and through learning.

It is also essential to consider that language learning and language use are two processes that must take place in the classroom for CLIL to be effective (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh 2010). In the observed classes, there were few situations for students to learn the language. The explanations given by the teacher did not match the learners' needs. Although it can be said that there was language use in the classes, it did not lead the students to learn, and the students' production was not previously planned by the teacher (as supported by the teacher's lesson plan analysis and by her journal); thus, we can say it was incidental.

Finally, it is important to suggest that although the learners used the vehicular language to communicate and achieved their purpose, the observed teacher should have been able to create opportunities for the students to develop the four skills and to recognize the learners' effort and success in order to facilitate their learning as recommended by the CLIL methodology.

In terms of cognition, different aspects were found. First of all, it can be said that there were many situations in which lower-order processing mental activities, such as remembering and understanding, were developed, and very few in which students developed higher-order processing activities such as analyzing, evaluating or creating, as the excerpt below shows:

T: Can you tell me the names of ecosystems?

S1: deserts

T: deserts very good! Give me one!!

S2: land

T: No, come on!!

S3: me!!

S4.: me, tundra.

T: yes, tundra

S5: taiga!

T: tundra

S2: tundra!!!

T: [tandra]!!!

S3: grass lands

T :grasslands

T: no?

S6: rain forest

T: tropical rain forest!

(June 3rd, 2010)

In terms of problem solving, it can be said that even though there were many opportunities in the classes, the students were not led to solve real-life problems in the classes. When they were learning about ecosystems, for example, they could have been asked about an ecological problem, or what would happen if an animal is removed from its habitat. Similarly, in addition to asking students to develop some pages of the textbook, more problem solving activities could be suggested in math class because of the characteristics of the content and because it is a very useful subject for real life.

As in any other class, the recorded classes allowed students to develop some cognitive process dimensions, such as understanding, analyzing, applying, creating per se; these happened accidentally instead of being planned and developed by the teacher in her classes. Thus, we can say that there are many aspects of cognition in CLIL that would need to be included in the observed classes.

In regards to the next category, culture, it can be said that students usually feel part of a community when they are working in groups because they may identify with their groups, they support the work of their classmates, and work in order to achieve success as a group. The teacher also considers that group work refers to culture. Regarding this aspect, she writes about how students organize themselves to work in groups, assuming and performing individual and group tasks.

In addition, it was found that the students' interest in knowing more about the target culture was evident. 92% of the students think they learn about the target language in their classes and they named some topics to illustrate their point of view in the questionnaire they answered, such as the US money system in math and the ecosystems in science. School staff also agrees with this fact. During an interview given by the academic coordinator, he referred to some cultural events they carry out in different periods of the year. They participate in different activities to celebrate specific foreign holidays like Saint Patrick's Day, or Valentine's Day.

However, if it is true that they have in mind cultural celebrations such as the holidays, these events are not a result of a continuous CLIL culture work. They are a product of a short period of time and insolated instruction and performance within the classroom. In addition, the classes should include, for example, the use of authentic materials and intercultural curricular linking because they are just two ways of helping students to understand the difference and similarities between cultures.

As a last comment about culture, it is essential to point out that even if there are some emergent aspects of culture in the classes, culture must be transparent and carefully planned before going into the classroom.

Because the set categories gathered from the data refer to just three of the 4 CLIL Cs (communication, cognition, and culture), it is a must to present what was found in terms of content, especially because it was present throughout all of the classes.

The first issue to point out is that although content in CLIL is flexible and "… can range from the delivery of elements taken directly from a statutory national curriculum to a project based on topical issues drawing together different aspects of the curriculum, for example The Olympic Games, global warming, ecosystems" (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010, p. 28), the school had decided to teach the whole science and math programs in English. Therefore, these classes are completely content led, which is not the aim of CLIL.

What happens in the context analyzed is that science and math are taught in English, but teachers do not have theoretical or pedagogical constructs about how this content-based learning would guarantee that students will learn the foreign language. Consequently, teachers teach without a careful plan on how English will be learnt and they think it will just happen.

Due to the lack of clear and transparent planning of the different aspects in the observed classes, it may be said that the content is not planned in terms of how students will access knowledge, skills, and understanding instead of simply knowledge acquisition, as CLIL suggests. The observed classes show that the teacher tries to illustrate students on a subject topic by different means such as oral explanations or readings for the learners to reproduce it and use it to do basic tasks such as a mathematical operation.

After carrying out a careful analysis of the information gathered, the data suggest that there are some pedagogical and methodological aspects about the observed classes that are worth pointing out. The teacher followed an organized structure during the classes. She provided warm up activities in all the lessons, then, she reviewed the previous topics, introduced new ones, suggested some exercises for the students to practice what they have learnt and tried to close the sessions with a general comment about the class or the topic discussed.

As the students wrote on the questionnaire, they like the classes because they are motivating. Most of the children seemed to be enjoying the lessons. They were participating and working actively. Furthermore, they had a nice attitude towards the class and towards the teacher. In addition, the teacher took the time to explain the topic more than once when necessary and she did it within the group and individually. The activities used by the teacher were varied and she included learning games and actions where kids worked on the four skills of reading, listening, speaking, and writing.

Despite all these positive aspects, it is necessary to point out that there are some CLIL characteristics that would need to be taken into account if the school were interested in implementing CLIL. First of all, the school needs to be clear on the methodology they wish to follow, and if it is CLIL, the school staff should have the necessary knowledge about CLIL to implement it in their teaching practice. Second, classes need to be carefully planned and lesson plans must be done following the CLIL requirements. It is also important for lessons to be developed in such a way that students can progress on the 4Cs: communication, cognition, culture, and content. Finally, teachers should have in mind that aspects such as classroom management and materials play an essential role when working with CLIL in the classroom.

Pedagogical Proposal

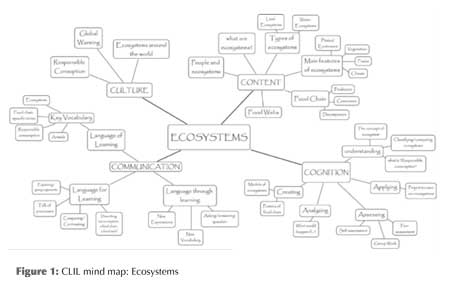

After analyzing the findings of the research, it was determined that aspects such as the need for teacher training in terms of CLIL, and CLIL lesson planning might play an important role in the teaching-learning process. Hence, a pedagogical proposal divided in two parts was carried out. In the first part, the observed and analyzed lessons were improved by planning them bearing in mind a model suggested by Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010). shown in Figure 1.

In the second part, a teacher training mini-program was suggested based on some of the most important CLIL theoretical constructs. The teacher training mini-program aims to provide teachers with the information they need for being able to successfully use CLIL in their classes and, consequently, to achieve the vision of the school, offering students an excellent bilingual education. In addition, this mini-program intends to become a tool for teachers to produce good CLIL lessons based on the main theoretical constructs of this approach. By designing and implementing the program, teachers are expected to acquire the abilities they require to become critical in regards to their CLIL teaching practice. The teachers training mini-program is designed to be developed in four sessions: Session 1: CLIL Principles - The 4 CLIL Cs, Session 2: The Language Triptych - Assessment in CLIL, Session 3: Planning a CLIL Unit, Session 4: A CLIL Lesson

Conclusions

Even if classes are taught in English at CBS, they would need to balanceintegrate content and language so they meet the CLIL criteria. At Country Bilingual School, classes are content-led, which does not allow CLIL to be completely effective as there must be a balance between content and language.

In CBS classes, there is teaching of language through content, but both content and language seem to be taught isolated. They need to be integrated in order to implement CLIL. Students are occasionally involved in learning. Students have the opportunity to interact among themselves and with their teachers, using the language for real purpose and in a given context. Students usually feel part of a group and have certain knowledge about the target culture aspects, yet, the concept of self and other awareness need to be reinforced. Students learn about math and science topics through the vehicular language; however, they are expected to use what they learn in their real lives. Other important aspects of a CLIL class, such as the scaffolding and lesson planning need to be carefully considered and calculated when using CLIL at CBS.

The application of the four CLIL Cs at CBS should be careful considered before using CLIL in the teaching process. Also, even if there are some incipient aspects of the four CLIL Cs in the classes at CBS, they happen incidentally, which is not ideal in a CLIL class. Thus, there must be complete planning on how the four CLIL Cs will be developed in the teaching and learning process at the school.

Teachers at CBS need to agree on the use of CLIL for all of them to begin applying CLIL in their teaching practices. Also, careful planning and awareness about the CLIL theoretical and practical constructs should be thoroughly considered.

In order to implement the CLIL practice at CBS, teachers must create complete and well-designed lessons plans. Correspondingly, teachers at CBS should be trained on CLIL for them to improve their teaching practice in terms of bilingualism.

Some aspects about the bilingual education at CBS may be improved. A shared vision about bilingualism needs to be reached by all the members of the community. A clear vision of what the school is doing and needs to do in terms of bilingual education is also important; and more importantly, a concrete and common methodology needs to be used by all teachers at the school.

Pedagogical Implications

Teacher training on CLIL in Colombia is essential. It might be possible that if teachers know about the topic, they will try to use it in their classes, contributing to the development of the education and bilingualism processes. Even though the research carried out was systematic and rigorous, it is important to point out that this is just a first step in the research of an area that needs to be widely and seriously explored, especially in our context. Research on CLIL must be done in order to have a better understanding about CLIL as an approach that can be used to improve our education, specifically, in terms of foreign language teaching.

Limitations of the Study

The limitations of the study refer mainly to the type of the study and to the fact that one of the researches was also the observed teacher. This research was carried out under the guidelines of a qualitative case study. This type of research is a process in which the researcher analyzes the specific and general characteristics of a given context. Because of the nature of case studies, it is not possible to establish generalizations about the findings of this study.

Similarly, the fact that one of the researchers was also the observed teacher constitutes a limitation of this study. Being the teacher and the researcher at the same time could have biased the research information because the same person was involved as a teacher and as the researcher. However, there was also a second researcher who observed the classes and gave a balance to the perceptions and the findings of the research, diminishing the possible bias in the study.

References

Bryan, N., & Habte-Gabr, E. (2008). Strategies for teaching geography electives in English to native Spanish speakers at a Colombian university. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning. 1(1). 1-14. [ Links ]

Buchholz, B. (2007). Refraining young learners' classroom discourse structure as a preliminary requirement for a CLIL-based ELT approach. IN DALTON-PUFFER C. & SMIT, U. (Ed.) Empirical Perspectives on CLIL Classroom Discourse. Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL. Content and language integrated learning. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

De Graaff, R., Koopman, J., & Weshoff, G. (2007). Identifying effective L2 pedagogy in content and language integrated learning (CLIL). Views, 16, 12-19. [ Links ]

Echevarria, J., Short, D., & Powers, K. (2006). School reform and standards-based education: How do teachers help English language learners? (Technical report). Santa Cruz, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity & Excellence. [ Links ]

Delgado, EL. (1998). Bilingual education programs: A cross-national perspective. Journal of Social Issues. 55 (4). 665 - 685. [ Links ]

Llinares, A., & Whittaker, R. (2006). Linguistic analysis of secondary school students' oral and written production in CLIL context: Studying social science in English. VIEWS, 15, 28- 32 [ Links ]

Marsh, D., Maljers, A. and A. K., Hartiala, (eds.): 2001, Profiling European CLIL Classrooms: Languages Open Doors, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä [ Links ].

Mehisto, P., Marsh, D., & Frigols, MJ. (2008). Uncovering CLIL: Content and language integrated learning in bilingual and multilingual education. Oxford: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1973). Memory and intelligence. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Seliger, H., & Shohsamy, E. (1990). Second language research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Ting, Y. L. T. (2007). Insights from Italian CLIL-science classrooms: Refining objectives, constructing knowledge and transforming FL-learners into FL-users. Views, 16, 60-69. [ Links ]

Yassin, S., Tek, O., Alimon, H., Baharon, S., & Ying, L. (2010). Teaching science through English: Engaging pupils cognitively. International CLIL Research Journal. 1(3). 46-59. [ Links ]

Zydatiß, W. (2007). Bilingualer fachunterricht in Deutschland: eine bilanz. Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen 36, 8-25. [ Links ]