Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

Print version ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.16 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2014

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.2.a05

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.2.a05

Research Article

EFL student teachers' learning in a peer-tutoring research study group1

El aprendizaje de futuros profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera en un grupo de estudio e investigación enfocado a la tutoría entre pares

John Jairo Viáfara, M.A.2

1 This article reports a side study conducted within the main project "Las Tutorías en el Programa de Licenciatura en Idiomas Modernos" founded by the research office at a public university.

2 Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. Tunja, Colombia. jviafara25@gmail.com

Citation / Para citar este artículo: Viáfara, J. J. (2014). EFL student teachers' learning in a peer-tutoring research study group. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 16(2),201-212.

Received: 29-Oct-2013 / Accepted: 23-May-2014

Abstract

In order to become peer-tutors in a BA program in Modern Languages, a group of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) student teachers attended a study and research group in a university. Throughout their participation, prospective teachers collaborated and reflected by means of task completion and dialogue to learn the theory and practice of tutoring and research. Additionally, participants provided survey, journal, and interview data to contribute to the exploration of how their group membership shaped them academically and personally. Results suggested that student teachers increased their knowledge of English due to their use of real-life group dynamics, among others. Furthermore, they updated and expanded their competencies to monitor pedagogical situations, design strategies, and solve problems.

Keywords: study group, research group, EFL student teachers' preparation, peer-tutoring, prospective teachers

Resumen

Con el fin de convertirse en tutores de sus compañeros en un programa de Lenguas Modernas, un grupo de estudiantes profesores de inglés como lengua extrajera asistió a un grupo de estudio e investigación en una universidad. Los futuros profesores colaboraron y reflexionaron por medio de tareas y diálogo para aprender la teoría y práctica respecto a tutorías e investigación. Igualmente fueron encuestados y entrevistados para explorar cómo su pertenencia al grupo los influenciaba académica y personalmente. Nuestro análisis sugiere que los estudiantes incrementaron su conocimiento del inglés al utilizar estrategias y ser expuestos a la dinámica del grupo basada en la vida real. Además, actualizaron y expandieron sus competencias para monitorear situaciones pedagógicas, diseñaron estrategias y resolvieron problemas en su práctica.

Palabras Clave: grupo de estudio, grupo de investigación, preparación de estudiantes profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera, tutoría entre pares.

Introduction

Investigating this issue became relevant for us since tutors participating in the group would become English teachers and this experience could probably shape their pedagogical and linguistic skills. In fact, many student teachers during the selection process to start as tutors expressed their expectations in regards to increasing their ELT methodological skills. Likewise, others manifested their willingness to improve their English proficiency. This study shares the interests of various Colombian scholars in exploring possibilities to build context-sensitive empowering EFL pre-service teacher education initiatives (Faustino & Cárdenas, 2008; Sierra, 2007; McNulty & Usma, 2005; Viáfara, 2008; Zuluaga, Lopez, & Quintero, 2009). The following pages summarize the theoretical principles behind the process to prepare EFL student teachers as tutor-researchers within the group. Furthermore, the next lines describe the process and tools which were used to involve participants in reflecting upon tutoring and learning about research. Then, we provide answers to the research question stated above and close by drawing some conclusions and pedagogical implications.

Peer-tutoring has been the focus of our research work in the BA program in Modern Languages in a public university for six years. In previous research and publications, we examined first semester students' learning as they were tutored by more advanced peers (Viáfara & Ariza, 2008; Ariza & Viáfara, 2009a). In this article, the focus of attention is shifted and last semester students' knowledge and ability development become the main issue under examination. Thus, we posed the following research question to guide our study: How does student teachers' membership in a study and research group shape them academically and personally as they tutor their first semester peers?

Literature Review

Several philosophies for the education of student teachers interacted in building the conceptual underpinnings of the strategy we enacted in our group. In general, our preparation model encouraged a reflective approach. Within this avenue, the perspective of the teacher as a researcher and the involvement of prospective educators in collaborative study groups were deemed essential. In general, by adopting a reflective approach, we sought to engage student-teachers in an in depth examination of their own practices as tutors of English. Therefore, our objective concurred with Lee (2005), "to develop teachers' reasoning about why they employ certain instructional strategies and how they can improve their tutoring to have a positive effect on students" (p. 699). In this vein, reflection was regarded as a critical thinking process student teachers employed to analyze their performance as tutors, make informed decisions, and reshape their actions by gaining awareness of their context. In addition, a reflective model buttressed our intention to foster student teachers' own reflection to take action, in contrast to providing them with pre-established methods to follow.

The working dynamics in our group meetings emphasized what Schön (1983) conceptualized as reflection on action. In this vein, the deliberation emanated from student-teachers' exploration of their previous tutoring experiences to understand the origin of their practices, their effectiveness, and options for improvement. Basically, the three levels of reflection that Hatton and Smith (1995) discuss based on (Fuller, 1970; Smith & Hatton, 1993; Valli, 1992) surface through the preparation strategies we designed. The descriptive level encompasses the analysis of instructional actions by unveiling the rationale behind them. The dialogic level implies stopping and carefully considering inner and outer thinking to evaluate and propose suitable

options in facing professional challenges. Finally, critical reflection requires substantial awareness of one's performance that affects others' lives and of the influence of social, cultural, and political consequences in teaching practices.

A reflective practice has traditionally been associated with teachers or prospective teachers' development of problem solving skills. By the same token, influential scholars have underscored the inquiry-oriented nature of this approach (Dewey, 1933; Schön, 1983; Richards & Lockhart, 1994; Zeichner, 1983). Given this, involving practitioners in research practices has emerged as a powerful means towards reflective teaching.

Research, in general, offers a valuable opportunity to support educators' learning. Carr and Kemmis (1986) and Wallace (1991) are among those scholars who have underlined the reflective nature of action research as a possibility for teacher education. This type of research incorporates the idea of teachers' acting meaningfully when their performance emanates from a processes of inquiry. At the personal, social, and political levels of what the teaching profession entails, research can become a tool to encourage practitioners' improvement (Elliot, 1990, p. 11).

Pre-service teachers' preparation by means of their engagement in research has been examined by scholars in our country and internationally. Locally, several Colombian universities have studied the incorporation of research components in their Licenciatura programas (Faustino & Cárdenas, 2008; McNulty & Usma, 2005; Viáfara, 2008). These experiences have suggested that most prospective teachers exhibit positive attitudes towards research, favoring the integration of the role of the teacher and the role of the researcher. Likewise, the use of research instruments such as journal writing and observation techniques increases student teachers' self-evaluation and self-awareness. Other scholars have found that research helps student teachers to integrate theory and practice (Smith & Coldron, 2000), to gain agency to act in their classrooms (Price, 2001), and to increase their skills to solve problems (Russell, 2000).

In contrast to the aforementioned benefits, Faustino and Cárdenas (2008, p. 425) revealed that participants in their investigation expressed their limitations to integrate theory and practice, keep records of information, analyze data, and formulate research problems. Viáfara ([29] 2008) found that student teachers felt overwhelmed having to cope with their pedagogical work while simultaneously conducting research. Constant monitoring and inter-institutional support should facilitate prospective teachers' education as they intertwine teaching and research.

Student teachers' possibilities to interact with peers by means of class discussions and teamwork were highlighted as key aspects generated by the inc lusion of research in their teaching. In our project, prospective teachers' tutoring and their research became the main source for reflection throughout the study group sessions.

Collaborative study groups have emerged as an alternative model for teacher development or pre-service teacher preparation. Diaz-Maggioli (2003, p. 8) defines collaborative study group as "small groups of colleagues who get together on a regular, long-term basis to explore issues of teaching and learning. In so doing, they support each other at the personal and professional levels." Scholars such as Diaz-Maggioli (2003) and Patnode (2009) have emphasized the need to center these groups on participants' needs, interests, knowledge, and contexts. The previous foundation requires a high level of democratic organization and participation to guarantee each member's self-direction as well as flexibility. Likewise, it is of paramount importance to guide participants to act and reflect upon their pedagogical practices by means of collaborative dialogue. Additionally, assessment processes can contribute to gauge the extent to which the group's foundational goals are or are not reached (Sanacore, 1993).

Studies by Sierra (2007), Álvarez and Sánchez (2005), Schecter and Ramírez (1992), Arbaugh (2003), and Musanti and Pence (2010) analyze how teachers expand and update their knowledge since they learn, review, and develop theoretical principles about pedagogy, their discipline, and research while participating in groups. Participants' cognitive skills are also enhanced at the level of questioning and argumentation. Educators' learning in study groups impacts their pupils since these teachers can better understand their students' needs (Clair, 1998). Paredes, Sawyer, Watson, and Myers (2007) underline the collaborative problem solving nature of study groups. Sierra (2007), Álvarez and Sánchez (2005), Clair (1998), Schecter and Ramírez (1992), Musanti and Pence (2010), and Nieto (2003) highlight that due to the collaborative nature of study groups, teachers become more autonomous, engage in negotiating relations with their peers, and start networking in more specialized groups. Furthermore, they seek to further their academic studies (Arbaugh, 2003).

Conversely, studies in this area reveal the constrains and tensions which are likely to emerge from study-group dynamics. Sierra (2007), and Álvarez and Sánchez (2005) identified teachers' excessive work load, reduced availability, lack of administrative support, and of participants' responsibility as aspects which could create instability in the functioning of the group.

The aforementioned theoretical and empirical considerations were considered when designing a platform for our group. In opening this academic space, we expected that the main researchers and student teachers would establish a community founded on their autonomy to contribute to their mutual growth as EFL educators. Bearing in mind that our common enterprise was the collective examination of peer-tutoring practices, we adopted principles of a reflective approach to move beyond the mere description of our actions into the critical assessment and subsequent formulation of solutions to problems. Similarly, learning about research constituted a cornerstone in our search for channels to boost reflection leading towards coherent and situated pedagogies. The following lines informed our process to assemble the group under the constructs discussed in the literature review.

Methodology

Participants

This research study involved fifteen student teachers who tutored peers for three consecutive semesters. They were in their six to nine semesters of studies. They attended the Modern Languages Program at a public university in Colombia. In addition to providing tutoring to their first semester peers, student teacher were expected to develop research skills so they could contribute in the design of projects, data collection, analysis, and socialization of results.

We conducted a systematic process to select tutors. The initial biographical and background information provided by applicants informed our selection. Decisions were made based on candidates' genuine interest in becoming tutors, their understanding of what this endeavor entailed, and their proficiency level in English. Student teachers, who were tutors at the time, joined the two main researchers to make the final decisions about new memberships.

Context

Meetings were held once a week for two hours in the School of Languages, and the main researchers and leaders, two professors in the program, provided the necessary logistic resources for sessions including equipment, worksheets, readings, and snacks. Most members usually attended sessions regularly; however, depending on their academic duties, and especially at certain times during the term, some of them decided not to attend. Meetings were generally led by the two main researchers who acted as facilitators. Sessions started by reading the agenda planned by the two leaders and the subsequent negotiation of possible changes among the participants in the gathering. Then, the plan was developed and finally a tentative agenda for the next assembly was accorded.

The sources to guide our study in the group were twofold. The first type encompassed theoretical material namely information in articles, reports, or books. Taking into consideration the objectives of the project, the core topics we discussed revolved around tutoring and research principles, autonomous learning, and the group logistics. The various instructional activities and the research around them became the second source for reflection. Thus, we analyzed what happened in the tutoring sessions, the implementation of research projects, the participation in the academic community, and aspects in connection with the use of English.

In regards to the study of theoretical principles, we read documents, listened to lectures or short presentations, and attended academic events. After being exposed to the material, participants shared their views with one or two peers and to close, the whole group would meet to deliberate on the topic being addressed. Student teachers were encouraged to connect the target texts with their specific experiences during their peer-tutoring or research practice.

The reflection on peer-tutoring practices centered on video recording, simulations of tutoring sessions, journals, and participants' narratives. After being in contact with the resources mentioned above, there was a space for reflection focused on the student teachers' interests. Problem solving tasks guided participants' work during sessions; they solved puzzles, designed alternative answers to problems, and built mind-maps, among others.

In the specific case of simulations, tutors or main researchers prepared sketches to recreate conflictive and/or common situations they experienced or had witnessed throughout the peer-tutoring sessions. Sometimes, the main researchers had chosen specific issues based on their data analysis since they had understood that such aspects needed special attention. In relation to journals, participants voluntarily read entries to share their experiences and to become familiar with their peers' views in regard to topics they considered difficult to handle.

In addition, we invested a substantial amount of time in analyzing research practices. Several of the elements mentioned before were also instruments to collect data and answer the questions we had posed for the main study. For instance, reading journals became an opportunity, on one hand, to involve tutors in analyzing how these instruments were functioning and their relation with the focus of the project, and on the other hand, these tools revealed connections between participants' experience in tutoring and the theoretical principles previously addressed. That was also the case for video and audio recordings which were employed to interview the tutees at the end of the term.

The group also focused on studying how research could be shared in academic communities. Thus, taking advantage of the main researchers and other group members' academic production, we organized short talks to demonstrate how presentations for academic events might be prepared. Similarly, the lecturers shared models of articles or proposals they had written or socialized. The study group provided feedback for the ongoing research work that any member of the group was conducting at the time, especially their thesis and projects directly connected with the group.

Data Collection and Analysis

The data we collected to investigate how becoming part of a study and research group shaped student teachers' preparation came from journals, surveys and documents, and end of term interviews within a qualitative approach. De Tezanos (1998) characterizes a qualitative approach as one focused on describing a social phenomenon which takes place in its natural setting. By means of this kind of investigation, researchers followed a process to understand their object of study, and to attempt to answer the research question.

Our first instrument was a survey which we applied to the fifteen student-teachers who attended the group. The questionnaire contained open questions to examine how participants' membership in the group related to their development of research, communicative, and pedagogical skills in EFL. We also examined participants' journals since they used them to record their views in regard to their participation in the group and their tutoring practices. The 12 journals we read belonged to the first cohort of tutors, and these participants had kept them for three consecutive semesters. The minutes of the meetings were secondary instruments. These documents detailed the agendas set for each gathering and summarized the central events and ideas of what occurred in the sessions. Finally, we included participants' answers to one of the questions in the end-of-term interview that we designed to evaluate their tutoring work. The question asked how they had felt being members of the group.

By means of principles rooted in the constant comparison method as described by Hubbard and Power (1993), information was classified and categorized. We read data several times in order to identify topics pertaining to our research focus. Subsequently, we defined and labeled patterns, and by systematically comparing, contrasting, and reducing data, we elaborated an organizational framework. That framework constitutes the answer to the question guiding this research.

Based on Janesick (1994), the member check technique was employed to give weight to findings. Thus, when the analysis of data ended, we presented participants with our findings. All the participants concurred that the results accurately represented what they had reported through the various data collection instruments. In addition, two means of triangulation were employed as described by Janesick (1994). The first technique was methodological triangulation since we collected information through various instruments. The second strategy involved researcher triangulation. The two leaders of the group analyzed the data separately under the dynamics described above and subsequently compared and contrasted their findings to establish the final categorization.

Findings

The data analysis processes led us to compose a framework anchored in three main topics to explain how becoming part of a study and research group shaped student teachers academically and personally as they tutored their peers in first semesters. These themes point at fundamental pillars in the knowledge base of EFL teachers. Firstly, student teachers' knowledge of their discipline was affected since they developed proficiency in the foreign language. Secondly, data evidences that they strengthened their pedagogical practices as a result of their group affiliation. Likewise, in regards to their general and content pedagogical knowledge, prospective teachers opened to positive attitudes and formative actions in employing research.

The Development of Proficiency in English

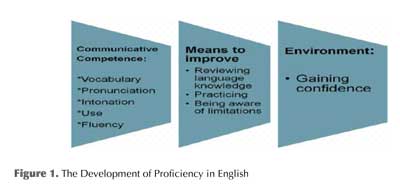

Figure 1. below reveals the connection we were able to establish among the three emerging sub-topics in the first main issue, the development of proficiency in English. The initial component of the figure exhibits the language skills and knowledge participants achieved. The data also informed us, as shown in the second part of the graph, of the practical actions and attitudes which bolstered the development of participants' language ability. The last section introduces the main contextual factor affecting student teachers' language improvement throughout the experience. The following lines unpack specific findings in each sub-topic.

In regards to their ability to use the foreign language, participants posited that by participating in the group, they acquired specialized academic vocabulary in relation to research and ELT methodology. Secondly, since their production of several sounds and intonation was constantly affected by their lack of practice and their regional accent, they perceived that their spontaneous oral interaction in the group provided them feedback to improve their speaking in the foreign language. The following extract illustrates the last point.

"Mejoré en el nivel de desempeño o fluidez en Inglés, porque como miembro de RETELE (Grupo de investigación) he adquirido nuevo conocimiento especialmente en cuanto a entonación. Me siento mucho más tranquila y segura a la hora de hablar en Inglés. Sin embargo soy consciente de las debilidades que aún poseo y en las cuales debo trabajar." (Survey, Student 2)

"I improved my performance level or fluency in English because as a member of RETELE (Research group) I have acquired new knowledge, especially in my intonation. I feel more at ease and confident when I speak in English. However, I am aware of weaknesses l still have to work in." (Survey, Student 2) Having the group as a real communicative context engaged participants in meaningful experiences of language use and boosted the learning of English. The context also seemed to encourage participants to increase their oral production.

Having the group as a real communicative context engaged participants in meaningful experiences of language use and boosted the learning of English. The context also seemed to encourage participants to increase their oral production.

The second part of the diagram demonstrates the means participants employed to progress in the aforementioned aspects. They expressed that their willingness to participate in group interactions led them to recall knowledge that they had learnt in previous language courses. Thus, they kept what they had learned "alive" by means of practice. Likewise, they were attentive to the communication problems they exhibited and kept those in mind to search for improvement possibilities.

"Es una gran oportunidad para usar lenguaje, mejorar la proficiencia practicando y aprender nuevos usos. Además se fortalece la confianza en uno mismo para hablar y en general usar mejor el lenguaje previamente adquirido cada vez. (Survey: Student 1)

"It is a great opportunity to use the language, improve my proficiency practicing and to learn new ways to use the language. Furthermore, one's self-confidence to speak is strengthened and in general the language previously acquired can be used better." (Survey: Student 1)

To close this first issue, the last piece of the scheme refers to an aspect which made a big difference for participants in their intentions to communicate by means of the foreign language. The group dynamics created a relaxing atmosphere in which participants were able to leave aside specific inhibitions generated by contextual factors, as the last piece of evidence revealed.

Strengthening Pedagogical Practices

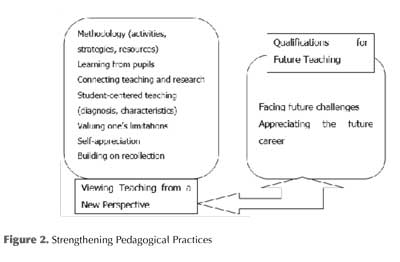

Student-teachers expressed that at the pedagogical level, their participation in the group had broaden their perspectives about the teaching of the foreign language. A list of the aspects they mentioned, as related to that wider horizon they perceived for their future profession as educators, has been included in Figure 2. To begin with, the various opportunities they shared and their reflection upon their work in tutoring put them in contact with materials and methodological strategies they had not employed before. Ideas from other tutors or their own tutees fed their creativity while these pedagogical options were brought into group discussions. A significant number of studies, summarized in the literature review, point at similar findings (Álvarez & Sánchez, 2005; Arbaugh, 2003; Musanti & Pence, 2010; Schecter & Ramírez, 1992; Sierra, 2007).

In accordance with the findings reported by Clair (1998), throughout their participation in the study and research group, student teachers developed a deeper knowledge of tutees' needs and personalities, among other characteristics. Participants' reflective attitude contributed to deeper examination of their tutees' profiles. They searched and analyzed their own previous knowledge as learners and discussed with their peers and tutees the positive or negative learning strategies they had employed. In so doing, they could prepare more alternatives for student-centered didactic frameworks to suit their participants' particularities.

"Necesitaba analizar, volver a mis experiencias anteriores, iniciales con el inglés por eso era necesario estar consciente de mis propias habilidades, mi proceso de aprendizaje, mi propia experiencia con el inglés. Fue positivo pues me fue posible compartir con los estudiantes a quien daba tutorías las formas como yo aprendía y como había sido mi experiencia y en lo posible mostrarles cómo hacer las cosas" (Interview: Student 3)

"I had to analyze, to go back, to my previous, to my first experiences with English so I had to be aware of my own skills, my own learning process, my own experience with English. It was good because I could share with my tutees how I learned and how my experience was and probably to guide them how to do things probably." (Interview: Student 3)

Similarly, student teachers claimed that being constantly involved in research activities, namely conducting surveys, listening to reports, or keeping a journal, encouraged them to perceive closely how research supported their teaching work in tutoring. Participants expressed that they became better observers and recorded key information that they later shared in the group with peers and in tutorials to create opportunities for reflection upon real-life experiences. They expected that tutees could take these accounts as points of reference to look at their own process.

By participating in the group, student teachers came to accept and value their limitations and were more at ease knowing they would encounter opportunities to gain more preparation. Their group membership granted them knowledge and practical experiences that they could use in their future practices with peers and tutees. Moreover, this setting triggered their memories to revisit previous knowledge which they employed to design suitable pedagogical strategies in tutoring. Overall, they felt more qualified to face future challenges because they understood in a broader sense what being a teacher who works collaboratively with others meant, and they seemed to increase their appreciation for their future profession.

"Unirme al grupo me ayudó a ver mi práctica como futura maestra trabajando en contextos reales, con problemas reales y contribuyendo al aprendizaje del Inglés de los estudiantes." (Survey: Student 1)

"Joining the group helped me see my practice as a future teacher, working in real contexts with real problems and contributing to students' English learning." (Survey: Student 1)

Opening to Research

Providing tutoring was always connected with investigation in our group. As main researchers, we expected to involve tutors in a constant exploration of what occurred in the sessions with tutees. From the evidence we collected, it seems that the dynamics student-teachers lived in the group led them to gain and find real spaces to apply knowledge of research. In addition to the connection between research and pedagogy explained in the previous section, the participants claimed that they learnt how to use journals, how to analyze the pertinence of a research question, or how to conduct a survey, among others.

"Porque aquí he logrado aclarar algunas dudas que tenía respecto al proceso investigativo, como formular preguntas para una entrevista, o la pregunta de investigación." (Survey: Student 5)

"Because here I have succeeded in clarifying some doubts I had in regards to the research process, for example, how to formulate questions for an interview or the research question." (Survey: Student 5)

Not only did student teachers strengthen those initial research skills they might have acquired throughout their program, they also enriched their perspectives of the nature of research and the options one can have to conduct it. Similarly, McNulty and Usma (2005), Faustino and Cárdenas (2008), and Viáfara (2008) found in their studies that when prospective teachers were engaged in research, they viewed this inquiring activity as a feasible enterprise for teachers. Thus, research was not stereotyped as an exclusive activity for professionals outside the teaching field. These and other myths around the practice of systematic inquiry seemed to be reshaped by tutors working in the group. One of the participants commented that "[d]e eso se trata el grupo, de despertar en los tutores la pasión por la investigación" (Survey: Student 4). "That's what the group is all about, to create in tutors the passion for research" (Survey: Student 4).

In regard to teaching and learning, participants also seemed to widen their perspectives when they looked at their pedagogical work from the myriad of angles offered by research. They perceived that they had more options to learn about what occurred in tutoring. For example, they collected data about the sessions, analyzed it, and shared their insights with peers in the group. The emerging knowledge from this process allowed them to gain a more integral view of what they could do as guides to support their tutees' progress. The previous findings intertwined with Smith and Coldron's (2000) findings about teachers' development of agency, and with Russell (2000) and Price's (2001) claims in relation to the problem solving skills teachers acquire by working in research.

Without a doubt, the support from the study and research group has been of paramount importance in guiding participants' practical and theoretical knowledge to conduct research. An increasing number of these prospective teachers have felt encouraged to start mini-projects and others have proposed or completed research studies in connection with peer-tutoring as monographs to fulfill a graduation requirement in the program. This is the case of the following student.

"Mi vinculación al grupo me ha brindado herramientas para desarrollar mini-proyectos de investigación en otras materias, como didáctica de Inglés. De igual manera me ha motivado para iniciar mi proyecto de grado teniendo en cuenta los principios de autonomía." (Survey: Student 1)

"My membership to the group has granted me the tools to develop mini-research projects in other subjects as ELT methodology. Similarly, this circumstance has encouraged me to start my final research project for graduation which will consider the tenets of autonomous learning." (Survey: Student 1)

Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

In order to examine how a study and research group bolstered student teachers' preparation for their tutoring work, we conducted an inquiry which informed us that student teachers' participation in the group allowed them to use language purposefully in an environment where they felt more confident. Participants regarded the aforementioned circumstances as directly connected to the improvement of their language competence, namely, vocabulary, pronunciation, fluency, and usage.

Study groups are indeed a powerful alternative to recreate genuine settings for language use. This might be the case especially when activities do not concentrate exclusively in academic events, but in addition favor social activities to promote group cohesion, empathy among members, and achievement recognition, among others. Encouraging a non-threatening environment in the study group has been possible due to the voluntary nature of participants' enrollment and the encouragement of mutual support among all participants in a safe atmosphere. For instance, participants have been granted control over the ways in which feedback upon their public speaking and writing within the group is delivered. In addition, an alternative and optional space for extra language practice has been opened.

Findings in connection with prospective teachers' pedagogical gains showed that they started to consider new pedagogical views when they partook in the group. These standpoints

centered on their sensitivity towards their tutees' needs and the particularities of learning contexts. Participants' reflection in conjunction with the dialogue they sustained with peers in the group enriched their knowledge of EFL teaching methodologies and learning processes.

The practice and reflection upon research seemed to favor student teachers' pedagogical skills as they became more capable of planning and employing research tools in solving problems. Likewise, they developed more appreciation for research as adjacent to their teaching work. Socializing research results has also been part of participants' accomplishments. They have presented papers in national conferences and published articles in journals.

In our country, the interest in involving student teachers in research during their practicum has increased in the last decades. Several studies have determined that despite the numerous gains, future teachers experienced similar constraints to those university professors faced when conducting research. (Faustino & Cárdenas 2008; Viáfara, 2008). Along these lines, we consider study and research groups a favorable avenue to guide student teachers in becoming habitual users of inquiry. This familiarity with research can be a further point of examination in order to understand the evolution of prospective teachers' research skills and knowledge throughout their undergraduate studies.

However, our study and research group was not exempt from challenges. Our difficulties matched those exposed in the literature (Álvarez & Sánchez, 2005; Sierra, 2007). In this vein, the lack of time for meetings became the most noticeable challenge. A strategy worth exploring to ameliorate the impact of this factor could be to connect the study group with relevant pedagogy and research courses in the curriculum. In so doing, there might be options to alleviate student teachers from some of the extra load that responsibilities in the group would bring while targeting common objectives for courses.

References

Álvarez, G., & Sánchez, C. (2005). Teachers in a public school engage in a study group. Profile, 6, 119-132. [ Links ]

Arbaugh, F. (2003). Study groups: Professional growth through collaboration. The Mathematics Teacher, 96( 3), 188-1992. [ Links ]

Ariza, A. & Viáfara, J. (2009a). Interweaving autonomous learning and peertutoring in coaching EFL student teachers. Profile, 11(2), 85-104. [ Links ]

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Basingstoke: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Clair, N. (1998). Teacher study groups: Persistent questions in a promising approach. TESOL Quarterly, 32(3), 465-492. [ Links ]

De Tezanos, A. (1998). Una etnografía de la etnografía. Bogotá: Antropos. [ Links ]

Diaz-Maggioli, G. (2003). Professional development for language teachers. Eric Digest,03-03. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. Chicago: Henry Regnery [ Links ]

Elliot, J. (1990). La investigación acción en educación. Madrid: Ediciones Morata. [ Links ]

Faustino, C., & Cárdenas, R. (2008). Impacto del componente de investigación en la formación de licenciados en lenguas extranjeras. Lenguaje, 36(2), 407-446. [ Links ]

Hatton, N. & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and teacher education, 11(1), 33-49. [ Links ]

Hubbard, R., & Power, B. (1993). The art of classroom inquiry. A handbook for teacher-researchers. New Hampshire: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Janesick, V. (1994). The dance of qualitative research design. In N. Denzin, and Y. Lincoln (Eds.). Handbook of qualitative research (pp.209-219). California:Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Lee, H. (2005). Understanding and assessing pre-service teachers' reflective thinking. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21, 699–715. [ Links ]

McNulty, M., & Usma, J. (2005). Evaluating research skills development in a Colombian undergraduate foreign language teaching Program. Ikala, 10(16), 95-125. [ Links ]

Musanti, S., & Pence, L. (2010). Collaboration and teacher development: Unpacking resistance, constructing knowledge, and navigating identities. Teacher Education Quarterly, 37(1), 73-90. [ Links ]

Paredes, J., Sawyer, K.,Watson, S., & Myers,V. (2007). Teacher teams and distributed leadership: A study of group discourse and collaboration. Educational Administration Quarterly, 43(1), 67-100. [ Links ]

Price, J. (2001). Action research, pedagogy and change: The transformative potential of action research in pre-service teacher education. Journal of Curricular Studies, 33(1), 43-74. [ Links ]

Patnode, L. (2009). Educator study groups: A professional development tool to enhance inclusion. Intervention, 45(1), 24-30. [ Links ]

Richards, J. & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge: CUP. [ Links ]

Russell, T. (2000). Introducing pre-service teachers to research. Paper prepared for Session 18.16. at the American Education Research Association. Retrieved from http://educ.queensu.ca/~ar/ aera2000/russell.pdf. [ Links ]

Sanacore, J. (1993). Continuing to grow as language arts educators: focusing on the importance of study groups. Washington: ERIC Clearinghouse. [ Links ]

Schecter, S., & Ramírez, R. (1992). A teacher researcher group in action. In D. Nunan (Ed.). Collaborative language learning and teaching (pp.192-207). Cambridge: CUP. [ Links ]

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic books. [ Links ] Sierra, A. (2007). Developing knowledge, skills and attitudes through study group. Ikala, 12 (18), 279 – 305. [ Links ]

Smith, R., & Coldron, J. (2000). How does research affect pre-service students' perceptions of their practice? Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/recordDetail?accno=ED446030. [ Links ]

Viáfara, J. & Ariza, A. (2008). Un modelo tutorial entre compañeros como apoyo al aprendizaje autónomo del inglés. Ikala, 13 (19), 173-209 [ Links ]

Viáfara, J. (2008). Pedagogical research in the practicum at Universidad Nacional: EFL pre-service teachers' conceptions and experiences. Revista Electrónica Matices, 2. Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/male [ Links ]

Wallace, M. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge: CUP. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K. (1983). Alternative paradigms of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 34(3), 3-9. [ Links ]

Zuluaga, C., Lopez, M., & Quintero, J. (2009). Integrating the coffee culture with the teaching of english. Profile, 11(2), 27-42. [ Links ]