1. Introduction

The global crisis generated by the COVID-19 disease has widened the economic, political, and social difficulties that affect developing countries. In Argentina, the situation was severe even before the pandemic due to reduced economic activity, fiscal deficit, state indebtedness, high unemployment, poverty, constant currency depreciation, and high levels of inflation (World Bank, 2021). In 2020, Argentina's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell 9.9%-the highest contraction since 2002-and the Monthly Estimate of Economic Activity accumulated a 10% drop (INDEC, 2020a, 2020b). Thus, the blockade exacerbated the existing recessive spiral. At the microeconomic level, companies suffered both financial problems and economic losses caused by the fall in the level of activity.

In addition to these difficulties, in the country about a third of the GDP is generated in informality (Schneider & Boockmann, 2017). Informal economic activity is all that contributes to GDP but is not currently reported (Dabla-Norris et al., 2008). Therefore, the informal economy includes underreporting income in formal firms or ‘partial informality’ (Perry et al., 2007), the activity of unregistered companies, and unregistered employment (Ulyssea, 2020).

This article focuses on firm informality, that is, not registered businesses and formal companies that report a lower level of revenue. Firm informality includes corporate tax evasion, since non-formal entrepreneurs evade all taxes and registered firms partially evade them by underreporting their revenues (Slemrod & Weber, 2012). Likewise, some studies use measurements of tax evasion to estimate the unofficial economy (La-Porta & Shleifer, 2008). This paper does not study informality in the labor market.

Given the complexity of the phenomenon, it is expected that the causes of underreporting income will be affected unequally during the COVID-19 crisis. On one hand, a higher degree of tax evasion may arise, given the Sharp drop in GDP and the prominence of smaller companies. On the other hand, with the reduction of the use of cash as a form of payment, a reduction in partial informality is also expected. The pandemic could also change the factors that motivate entrepreneurs to operate informally and/or comply with tax obligations.

In relation to unregistered companies, the pandemic crisis could also promote two different types of effects: a reduction of informal firms due to their low capacity to deal with crisis or an increase of them because they become a survival alternative for unemployed people or formal entrepreneurs who have closed their companies.

Those economic structural problems added to the high levels of informality in Argentina posed a difficult initial outlook to face the crisis generated by COVID-19. As mentioned, for firms, the motivations to remain or engage in informal activities were affected in different directions. For the government, the pandemic raised double challenges to public revenue, increasing the expenditure and decreasing tax collection. Therefore, this work proposes the research question: How does the pandemic crisis impact on informality of smaller companies from Argentina?

This article aims to analyze the impact of the pandemic crisis on the informality of micro-, small-, and mediumsized enterprises (MSMEs) based on the perception of commercial entrepreneurs and certified public accountants (CPAs). To achieve the proposed objective, qualitative research with exploratory-descriptive scope was conducted. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with eight retail entrepreneurs and eight public accountants from Bahía Blanca (Argentina). In qualitative content analysis (Flick, 2013), the initial coding followed a deductive design based on theory, while intermediate categories were identified through data-oriented inductive análisis (Schreier, 2013). The triangulation of the data sources was carried out combining interviews with entrepreneurs, public accountants, and documentary review. The Atlas.ti 9 software was used for data analysis.

Unlike much of the literature on informality in the period of crisis follows a quantitative-macroeconomic approach, this article presents a microeconomic study using recent qualitative primary data. Thus, the findings are useful for public policymakers because they would allow them to understand the underlying qualitative factors of the sluggish economy, considering that the informal activity accounts for a large part of the GDP of developing countries.

Besides this introduction, the article is divided into 5 sections: Section 2 sets out the background on informality; Section 3 describes the methodology used to do the work; Section 4 displays the results and describes the primary collected data; Section 5 presents the discussion; finally, Section 6 shows the contributions of the article to formulate public policies, pointing out its limitations and future lines of research.

2. Informality and its impacts on public accounts

The informal sector can create a vicious circle: individuals or companies go underground to evade taxes and social security contributions, thus eroding tax bases and reducing tax revenue. This results in a decrease in the quality and quantity of public goods and available services that encourages increases in tax rates on the formal sector, with the consequent generation of greater incentives to take part in the informal economy (Schneider & Enste, 2000).

For decades, the informal market has been one of the most significant and persistent challenges in Latin American economies. The COVID-19 crisis has widened the region's pre-existing structural weaknesses, including informality (OCDE, 2020). In this context, informal firms, i.e., small-scale and low-organization companies are among the most affected segments by the pandemic (Basto-Aguirre et al., 2020).

There is a high heterogeneity in the incidence of informality across countries. In the case of Argentina, average macroeconomic estimates for the period 1991-2015 indicate that the informal economy amounts to 24.10% of the GDP (Medina & Schneider, 2017) and reached 28.65% in 2016 (Schneider & Boockmann, 2017).

According to International Monetary Fund statistics, Argentina is the second Latin American economy with the highest value-added tax (VAT) gap representing a loss of 3.7% of the GDP in 2017 (Gómez-Sabaini & Morán, 2020). In relative terms, VAT evasion ranged from 19.8% to 34.8% in the period 2001-2007 (Gómez Sabaini & Morán, 2016) although estimates for 2017 indicate that the level of VAT evasion was 33.6 (Gómez-Sabaini & Morán, 2020). Considering corporate income tax, the rates of evasion are higher than VAT around 49% (Pecho-Trigueros et al., 2012).

The intrinsic motivation to pay taxes-or tax morale-is one of the factors that influence the behavior of taxpayers in relation to their tax obligations (Chelala & Giarrizzo, 2014). In this sense, tax morale is relatively low in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and has deteriorated since 2011. In 2015, more than half of Latin Americans (52%) were willing to evade paying taxes if possible (OECD et al., 2018). In Argentina, the high value of the weighted tax morale index (8.9), even higher than that of LAC (7.94), indicates that a large part of the population considers tax evasion highly justifiable (OECD et al., 2018).

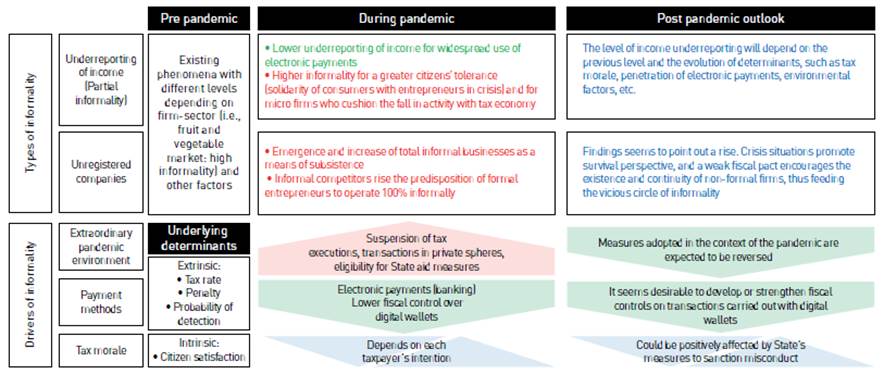

The next subsections are organized as follows: Subsection 2.1 discusses previous studies on informality, tax evasion, and tax morale in crisis contexts; subsection 2.2, summarizes the empirical evidence on informality and payment methods; and subsection 2.3 addresses the complex link between these themes in the COVID-19 context. Figure 1 illustrates and summarizes the relationship between the topics discussed below.

Fuente: own elaboration

Figure 1 COVID-19 crisis, electronic payments, and informality: a complex relationship.

2.1 Informality and tax morale during crisis

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, some research explored the effect of crisis on the informal economy and tax evasion, e.g., the 2008 financial collapse1. These studies indicated two possible relationships between the economic cycles of the official and informal sectors: the income effect and the substitution effect (Bajada & Schneider, 2009).

According to the income effect, the recessions promote a reduction in consumption in both the official and hidden economies (pro-cyclical trend) (Bajada, 2003; Bajada & Schneider, 2009). Instead, the substitution effect indicates that the informal economy acts as a buffer by increasing its size in periods of crisis (countercyclical behavior) (Bajada & Schneider, 2009; Bitzenis et al., 2016; Buehn & Schneider, 2012; Colombo et al., 2016; Davidescu & Schneider, 2019).

Regarding the behavior of tax evasion in times of crisis, Matsaganis et al. (2012) identified in Greece a slight growth in the underreporting rate in individuals with higher income levels. In this country, according to Bitzenis & Vlachos (2017), 40% of the surveyed people justified the unregistered activity in the economic impact of the crisis, with a higher approval rate of informality of self-employed workers and entrepreneurs.

In Portugal, Magessi & Antunes (2015) compared two citizen strategies to face the crisis, emigrate or evade taxes, and noted that most agents prefer to commit tax evasion, rather than leaving the country in search of better living conditions. In Spain, Alarcón-García et al. (2016) reported that, in times of crisis, there is an increase both in the perception that the tax system is unfair and in the intolerance to fraudulent behavior.

Research on the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on informality and tax evasion is still incipient. However, some studies analyze the impact of the economic recession on unregistered employment (Alfaro et al., 2020; Moreno & Cuellar, 2021). For example, in the case of Mexico, evidence indicates that the informal sector does not replace formal job losses, supporting a pro-cyclical behavior (Moreno & Cuellar, 2021).

Other investigations assessed the effect of COVID-19 relief measures as payroll tax cuts. For example, China completely exempted most companies from making social security contributions. Cui et al. (2020) calculated that the high informality of work makes 54% of the registered companies; it implied that 24% of the aggregate economic activity did not receive benefits. Despite these unfortunate findings, the authors also noted that the benefit of tax cuts-related to operating costs and business liquidity- are perceived by both smaller companies and the industries most affected by the COVID-19 shock because they are more labor intensive.

Furthermore, considering that the COVID-19 pandemic has raised double challenges to public revenue by increasing the level of spending and decreasing tax collection, policymakers are seeking new sources of revenue to bolster state budgets. In this context, ‘taxing the informal economy’ or ‘expanding the tax network’ have become popular topics of discussion, especially in countries with high levels of informality (Gallien et al., 2021).

Moreover, in the COVID-19 era, the approach of the social contract to the tax problem resurfaces. Many companies remained closed because of the blockade and had no source of revenue, but they had to comply with their tax obligations with the State anyways. According to the Abumere (2021) discussion, there was no consensus or canonical agreement on whether entrepreneurs and small businesses should pay taxes to the government or not during the crisis period.

Another group of authors studying the themes of informality and tax evasion used pre-pandemic data, but they applied the results to project political implications for the COVID-19 period. Pierri et al. (2021) analyzed the impact of audit programs on reducing tax evasion in Paraguay and developed a tax panel that identified discrepancias in company declarations. Their findings show that audits are effective in addressing tax evasion, and that the panel can guide criteria for more efficient fiscal control, which is particularly important during COVID-19 times. According to their results, in less developed countries, government audit activities are key to improve tax collection.

In addition, studies using European data propose a voluntary dissemination initiative to bring informal companies and undeclared workers to the state radar (Williams & Kayaoglu, 2020), especially for high informality economic sectors like the tourism industry (Williams, 2021). Before the pandemic, the dominant approach used by the government to tackle the undeclared economy was based on cost-benefit ratio. To turn legal actions into a rational choice, the State sought to raise the costs of engagement in undeclared jobs, increasing sanctions and the likelihood of detection. However, in the COVID-19 era, the use of penalties and the risk of detection are obsolete because most undeclared or informal companies have ceased. Nevertheless, improving the benefits of declared work to attract workers and businesses to the formal economy is still an option. A voluntary disclosure scheme encourages companies and workers to declare their provision of services, with or without penalty, and in return, they could access the temporary financial support available to declared companies and workers.

2.2 Informality and electronic payment methods (EPMs)

Several studies explain that cash is the payment method that eases tax evasion and informality, since the probability of being detected by the State for not declaring is greater than when the operation is implemented through banking or digital modalities. A large part of the empirical studies assessing the association between EPMs and informality are macroeconomic investigations conducted in the European context. For example, Schneider (2010) documented a strong negative correlation between the prevalence of EPMs and the informal economy. Reimers et al. (2020) analyzed cashless methods in conjunction with the role of the unofficial economy between 2002 and 2019 and found a positive relationship between household cash holdings, the volume of transactions, and the size of the informal sector, regardless the country size.

Regarding tax evasion, using 2002-2012 data from 25 European countries, Immordino & Russo (2018) found a negative relationship between the evasion rate of VAT and payments with debit and credit cards, thus showing that EPMs make evasion difficult. In an earlier study on the same topic, Immordino & Russo (2014) analyzed a collaborative tax evasion model where buyers and sellers negotiate a price discount for payment in cash in exchange for not issuing an invoice. Based on their results, a combination of two policy instruments could reduce tax evasion: a tax refund for the buyer requesting the invoice, and a tax on cash withdrawals.

At microeconomic level, Arango-Arango et al. (2020) studied the acceptance of EPMs in small business in Colombia. According to their findings, the expectation of higher taxes on the disclosed information about their sales is negatively associated with the decision of entrepreneurs to accept debit and credit cards.

2.3 Informality and electronic payments during the COVID-19 crisis

As seen in subsection 2.1, crisis promote several effects on the informal economy and, as explained in subsection 2.2, these shadow economic activities have an inverse relationship with electronic payments. However, the current COVID-19 crisis has some peculiarities; hygiene and isolation measures encourage electronic payments rather than cash, thus forcing companies to make a greater statement of their sales, then reducing partial informality.

On one hand, during the pandemic, a larger portion of the population was forced to use electronic payments, especially elderly users, informal and traditional companies, and people outside the banking system through the expansion of non-bank financial institutions. According to the Kantar COVID-19 Barometer, on average 70% of users in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico indicated that they would continue to use electronic payments once the health emergency was over, instead of returning to the use of cash (United Nations et al., 2021).

On the other hand, as LAC and Argentina have high informality and low access of informal companies to the banking system, the expected increase in the use of EPMs may be limited, also restricting its positive effects due to the formalization of operations. In fact, by 2017, half of the population in LAC did not have an account in a financial institution, and at the beginning of the pandemic more than 50% of employees were informal. In addition, informality among self-employed workers was more than 80%, and among firms with fewer than 10 employees, it was more than 70% (Salazar-Xirinachs & Chacaltana-Janampa, 2018).

These figures impose fundamental limitations on the sustainability of the growth of electronic payment in the region. Participants in the electronic payments sector agree that the biggest challenge to unlock the potential of electronic and digital payment systems in a sustainable way in LAC concerns the reduction in informality and the increase in financial inclusion (United Nations et al., 2021).

In short, the link among COVID-19 crisis, electronic payments, and shadow economy is complex given the interrelation between involved factors, making it difficult to determine the net effect of the recession on informality.

3. Methodology

As explained in the introduction, the article presents a qualitative research with an exploratory-descriptive scope. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with eight commercial entrepreneurs (retail) and eight CPAs from Bahía Blanca (Buenos Aires, Argentina) between September 2020 and May 2021 (Table 1). Each CPA answered the questions based on their professional experience. A mixed sampling was used by combining two typologies oriented to qualitative research: theoretical and for convenience (Hernández-Sampieri et al., 2014). The sample size was determined by saturation in sixteen interviewees -8 individuals from each group.

Table 1 Interviewees’ profile.

| Clients’ portfolio | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Certified Public Accountant | Activity / sector | Tax regime, legal status, firm-size | Interviewee: age, gender |

| CPA1 | Diverse. | Diverse. | 53, female. |

| CPA2 | Services (gastronomy), commerce. | Mostly VAT registered taxpayers, sole proprietorships, labour cooperatives. | 34, female. |

| CPA3 | Diverse. | Mostly VAT registered taxpayers, sole proprietorships. Only two partnerships. | 53, female. |

| CPA4 | Commerce, industry, and services. | Sole proprietorships and partnerships. | 40, male. |

| CPA5 | Most commerce, some services. | Half sole proprietorships and the rest partnerships. Mostly small firms, some medium-sized companies. | 45, male. |

| CPA6 | Agriculture, commerce, services (transport, health, financial). | Mostly VAT registered taxpayers, medium-sized firms. Very few simplified regime taxpayers. | 48, female. |

| CPA7 | Industry, commerce, services, agriculture, construction. | Diverse. | 49, male. |

| CPA8 | Commerce, industry, and services. | Mostly micro and small firms and some medium sized ones. Diverse legal status and tax regimes. | 30, male. |

| Characteristics of the commercial company | |||

| Commercial entrepreneur (CE) | Category, firm-age (years) and neighbourhood. Closed time due to pandemic (days). | Legal status, tax regime, number of employees. Others. | Interviewee: role, gender, age, education level |

| CE1 | Wholesale and retail of natural foods, 10, suburb [Santa Margarita]. 210, online sales only. | Sole proprietorship, simplified regime taxpayer, 1. In transition to limited partnership and to VAT general regime. | Owner, female, 32, incomplete college. |

| CE2 | Wholesale and retail of cleaning products and machinery, 15, suburb [Pedro Pico]. Never. | Limited partnership, VAT registered taxpayer, 3. | Partner, female, 42, incomplete college studies. |

| CE3 | Retail sale of babies and children’s clothes, 10 (3 with current owner), downtown. 150. | Sole proprietorship, simplified regime taxpayer, 0. Informal partnership between two friends. | ‘Partner’, female, 42, incomplete college. |

| CE4 | Production and sale of chicken products and minimarket, 13, suburb [Universitario]. Never. | Sole proprietorship, VAT registered taxpayer, 2. | Owner, female, 60, complete secondary. |

| CE5 | Photocopier and commercial-school bookstore, 25, suburb [Universitario]. 24. | Sole proprietorship, simplified regime taxpayer, 0. The only employee resigned in the pandemic. | Owner, male, 43, complete secondary. |

| CE6 | Retail sale of men's urban clothing, 9 (5 with current owner), suburb [Villa Mitre]. 100. | Sole proprietorship, simplified regime taxpayer, 0. Informal partnership between brothers. | ‘Partner’/ manager, male, 27, complete college studies. |

| CE7 | Commercial-school bookstore and computer inputs, 22, downtown (2 branches). 48. | Sole proprietorship, VAT registered taxpayer, 5. Family firm. | Owner, male, 59, complete secondary. |

| CE8 | Retail sale of sportswear, 1, suburb [Altos de Palihue shopping center]. 150, only online sales. | Sole proprietorship, simplified regime taxpayer, 1. Informal partnership between 2 friends. | ‘Partner’, male, 53, complete college studies. |

Source: own elaboration.

The choice of companies in the commercial sector as the unit of analysis is justified for the conjunction of two reasons: the incidence of informality in the sector and the operation of enterprises during the pandemic. Regarding the first reason, according to previous research studies, companies in the service sector (Santa María & Rozo, 2009; Abdixhiku et al., 2017) and retail sector (Pedroni et al., 2020; 2022) are more likely to work informally. Regarding the second point, in Argentina, during the mandatory lockdown a few companies within the service sector were authorized to operate (mainly those considered essential like health, cleaning, and food stores), but most of them-such as restaurants, hotels, gyms-remained closed until end 2020. Instead, in the commercial sector, companies were closed at the beginning of the pandemic, but they were able to continue selling online. Moreover, the reopening of physical stores in the commercial sector started around June 2020, earlier than in the service sector.

Therefore, retail firms are an interesting type of business for this study due to the level of informality and because their operations were less truncated by the pandemic compared to the services sector. Moreover, the continuity of retail firms’ operations during the quarantine allows exploring the crisis effects and the change in activity-level and sales-collection methods on the phenomenon of informality.

As seen in Table 1, the days the shops were closed differ among them due to the quarantine and distancing policies set up in Argentina for each sector. These measures were classified in five phases: three initial stages of lockdown, and phases 4 and 5 of distancing. The first phase of "strict isolation" went from March 20 to April 17, 2020; the “managed isolation” went from April 18 to 26, 2020; and from that date until June 4, 2020, the "geographical segmentation" took place. During phases 1 to 3, the activities and services declared essential were enabled to work. In the third stage, between May and June 2020, depending on the region, the opening of the commercial activity of most non-essential items began, except for clothing and footwear stores that reopened in June or July 2020, also with variation by provinces. Commercial stores in galleries or malls were the last authorized to work. Since November 2020, the distancing measures began to apply, which correspond to phase 4 "progressive reopening" and phase 5 "new normality" (Ministerio de Salud de Argentina, 2022).

The data collection instrument and interview script were tested in a pilot phase and then modified and improved. The final version consisted of four parts: (i) profile of the interviewee; (ii) level of activity and economic-financial impact; (iii) innovation2; (iv) informality and tax compliance. All interviewees signed a participation agreement that guarantees anonymity and confidentiality of information.

Qualitative content analysis (Flick, 2013) was used to describe the meaning of data assigning codes to the collected material. The initial coding followed a design based on deductive theory, while intermediate categories were identified through data-oriented inductive analysis (Schreier, 2013). The codebook with the name and description of each category is displayed in the results subsection. The triangulation of the data sources was carried out combining interviews with entrepreneurs, CPAs, and documentary review. The Atlas.ti 9 software was used for data analysis.

4. Results

In the next subsections (4.1 and 4.2), the results are organized as follows: first, the codebook is presented in Table 2 including the names and description of the categories created from content analysis. Second, the interviewees' citations are included to explore and illustrate each final category.

Table 2 Codebook: informality.

| Categories: name and description | ||

|---|---|---|

| Initial | Intermediary | Final |

| Informality: the pandemic crisis and the state aid measures passed as a consequence have an impact on the level and on the mobilizing forces of the different | Types of informality: the different types of informality are affected by the pandemic crisis. | Partial informality: underreporting sales by registered companies. Unregistered firms: companies not registered with the corresponding State and tax agencies. |

| Informality drivers: factors that influence the phenomenon of informality and may be affected by the pandemic situation. They can come from the company (payment methods), the taxpayer (tax morale) or the environment (extraordinary pandemic environment). | Payment methods: there are different current payment methods (cash, banking, and digital), each one has a link with informality, and their use level varied with the pandemic outbreak. Tax morale: intrinsic motivation of taxpayers to tax compliance. Extraordinary pandemic environment: extraordinary measures issued by the State in the framework of the pandemic and the completion of retail operations in private spaces produce collateral effects on informality and tax payment. |

Source: own elaboration.

4.1. Types of informality

4.1.1 PARTIAL INFORMALITY

CPAs and entrepreneurs highlight different factors related to the recession caused by the pandemic and the level of partial informality in Argentina. However, the net balance made by the interviewees is different; although the CPAs do not identify a dominant force, for entrepreneurs the increase in informality prevailed. In the words of CPA4, "there are many examples where the pandemic has caused companies to start reporting more sales, and others started reporting less."

On one hand, the widespread implementation of e-commerce and EPMs in response to blocking restrictions discouraged informality. On this, the accountants mention that "with the issue of digital payments and (...) online sales, you had no way to increase informality" (CPA4). In fact, "everyone started using debit and credit cards (...). Then, from one month to the next, (companies) sales doubled because obviously if you sell through debit/ credit (card) you had to issue an invoice, (...) and now the line is continuous (...) sales have increased and then been sustained over time (...) (November 2020)" (CPA3). In short, according to the accountants, the pandemic "made informality more evident" (CPA7) and "many people felt trapped because if they had planned not to invoice or to operate off the record, they could not do so" (CPA3).

In the same vein, entrepreneurs say: "I have many colleagues who complain because every time they report higher sales, suddenly they are categorized as VAT registered taxpayers (...) because no one uses money anymore, everyone is paying by debit card" (CE1). However, some entrepreneurs point out that the positive effect of EPMs in reducing informality was only in the initial phase of the pandemic. For example, CE3 mentions that "(informality) did not increase so much with quarantine (...) during strict lockdown everyone worked completely within formality (...); entrepreneurs accepted bank transfers and virtual wallet transfers, but now (...) they ask customers to come in person and pay in cash or transfer to another (non-commercial) account (...). We're trying to make our last effort to save something we couldn’t (...) (so) now everything is more informal."

On the other hand, the interviewees recognize two situations that may encourage income underreporting. First, the use of billing as an adjustment ‘variable’: small, registered businesses that deaden the actual decline in activity by increasing sales underreporting. For instance, marginal companies that sold to the final consumer and had a low percentage of reported income behave that way. With the pandemic, most of them experienced a fall in sales in real terms, therefore, "underreporting income is still high to try to generate fiscal savings that compensate for its real decline" (CPA5). Likewise, entrepreneurs emphasize that "each one tried to survive in the best possible way, if someone was informal before, I believe that now it must have been accentuated because there is no way forward… and I have always worked. Imagine the companies that had to remain closed for months, how do they handle moving forward afterwards? It is impossible; the numbers do not add up" (CE4).

A second factor that encourages shadow activities is the greater tolerance of informality on the part of consumers who empathize with entrepreneurs in crisis times. In this sense, CPA6 mentions: "not asking for an invoice and not giving it is much more accepted by consumers (...) this is more sympathetic to the entrepreneur."

Considering income underreporting, accountants also point out other two interesting aspects. First, in certain economic sectors, the phenomenon of informality is intrinsic to the activity and pre-existing to the pandemic. For example, according to CPA3, "in fruit and vegetable markets, the level of informality is atrocious (...). The producer already invoices the wholesaler with a price that is less than half the real value (...). But this has been happening for years, there is a lot of informality." Second, given the widespread phenomenon of income underreporting, accountants mention the impossibility of knowing the actual level of sales of their customers, since they are only aware of the reported sales. In the words of CPA3, "what caught my attention with the minimarkets (...) was the actual volume of (sales). Because, if your activity continued without any consequences, then the collect of payments by (debit/credit) card generated the billing, which did not happened before because customers paid in cash.”

4.1.2 UNREGISTERED COMPANIES

Although the phenomenon of informality existed before the pandemic, according to the interviewees, the widespread economic recession and the increase in the unemployment rate caused the emergence and rise of totally informal businesses as a means of subsistence. About this, entrepreneurs say that “it’s the country we live in, not just during the pandemic, with all of it, the unemployed people (informality) grew" (CE2).

According to CE2, entrepreneurs from the clothing industry are losing market because, in addition to fighting the crisis, they face competition with showrooms, which sale their product at 50% off because they operate in complete informality, so they have very low expenses. In fact, nowadays there are many more showrooms or informal shops because people try to do what they can to survive. The accountants mention that many entrepreneurs signed up for digital wallets, but they did not register in tax agencies, not even as simplified taxpayers. Moreover, they continue operating in this way, although accountants warn them to formalize their situation with the tax agency (CPA8).

Entrepreneurs also explain that the pandemic crisis increased the predisposition of registered businessmen to operate informally to evade taxes. Many people who lost their jobs have informally begun to open clothing companies, food companies, and other ventures that are fleeing tax payments. Formal entrepreneurs are dissatisfied considering the situation of informal ones, who do not pay taxes at all: "I pay ARS 800 million in taxes and they pay nothing" (CE6).

Therefore, many entrepreneurs think about going down the path of evasion, as CE7 explains: "I would be happy to close this business and go homeworking and be with my son, without employees. I would maintain all the customers and start selling off the record." According to CE7, informality seems to bring some benefits, such as spending less on rents and formal salaries and reducing potential labor conflicts. Therefore, considering these ‘benefits’, an incentive to operate totally in the informal sector is generated, as CE7 expresses: "I have a formal structure and pay taxes, while the unregistered firm has none (...) so the informal company grows more than me..."

4.2. Informality drivers

4.2.1 PAYMENT METHODS

Regarding the relationship between payment methods and income underreporting, the interviewees' answers outline three strata: two opposing poles (cash and banking modalities) and an intermediate level integrated by digital methods (virtual wallets).

For both types of respondents, income underreporting is associated with cash payments. In the words of entrepreneurs, "what you sell through a (credit-debit) card is all declared, but what you charge in cash sometimes is on the record, sometimes it is not, it depends..." (CE4); "I am obliged to fully report payments with card and digital wallets, but I declare 20%-25% of cash payments" (CE6). According to the entrepreneurs, they offer discounts for cash payments as a commercial strategy thanks to the tax savings generated by underreporting sales: "I explain to the consumers: if you are going to pay with (credit-debit) card, I have to issue an invoice and the price is higher (for tax reasons). So, I encourage the customer to get cash at an ATM and (...) I give them a 20% discount." (CE7).

In line with entrepreneurs, the accountants claim: "cash is what allows you to deal with a certain informality" (CPA2, CPA3). CPA5 expresses that "the State (...) closed tax evasion routes by banking many of the operations. In other words, (…) the movement of cash (…) led the company to have much more room for maneuvers than to have remarkable records, such as bank transactions." Other accountants add that "everything that passes by card (...) is religiously billed" (CPA7) and if not reported, "it is very easy to detect by the tax agency" (CPA8).

The virtual wallets are in the middle between cash and banking methods. The interviewees, especially the accountants, recognize that electronic wallets are subject to less fiscal control in relation to banking modalities, but monitoring has increased during the pandemic due to the exponential growth of their use. In this sense, the accountants express: "I think that with some methods (electronic payment), it is possible to deal with more informality than with others (...). With certain methods the fiscal control is lower, especially in recent virtual modalities originated by new technologies” (CPA2). For CPA5, "new payment methods appear (...) where the control that the State has achieved over banking modalities is beginning to be lost, because of the new (technologies). In the future, this will begin to be regulated... For example, (...) when you request an account summary of a digital wallet, it is an ethereal spreadsheet that has no tax withholding ... I don't know how much information tax agencies have on this..."

Regarding the increase in state monitoring of digital payment methods during the pandemic, CPA8 explains that "there is a lot of difference between banking and digital modalities. At least today, there are differences (...). In the future, they will tend to disappear due to a matter of ... fiscal interest." Similarly, entrepreneurs express that "after the pandemic, something that was a vacuum began to be controlled: virtual wallets. It was not controlled. I believe that as most businesses begin to sell this way (...), the State will start tax-auditing" (CE2).

In addition to less tax control over digital methods, entrepreneurs recognize that underreporting sales collected through digital wallets is possible due to the lack of link between the virtual account holder and the business owner, and due to the use of non-commercial options of payment applications. Regarding the first point, some entrepreneurs mention that "today, in Argentina someone who has the Posnet3 digital wallet can sell off-the-books, because everyone has a Posnet, not only registered companies. So, if you look at Facebook-Marketplace and someone is selling shoes in 12 monthly payments, this person can use the Posnet in his cell phone, from his house, collect the payment using a credit card, and still it will not be controlled by anyone (...). Today, if you go store by store and ask owners if they linked4 the Posnet virtual wallet to their business, I can guarantee that no one did (...), if so, they will have to bill!" (CE5).

Regarding the second factor, the accountants explain what happened to the option of ‘money transfer’ of a popular digital wallet, "something electronic that lent itself to informality was the digital wallet (...) because it offered an alternative to transfer funds without being a commercial operation, but then it was over. Obviously, the government noticed this and (...) began to apply tax withholdings and more controls" (CPA7).

4.2.2 TAX MORALE

Beyond the pandemic context, interviewees point out the importance of the business owner's intention regarding the invoicing. According to entrepreneurs, regardless of the payment method, billing depends on their intention: if you charge in cash and issue the invoice nothing happens, it is the same procedure with a card. "The point is that we all avoid the formality to try to save taxes (...), it depends a lot on the entrepreneur's intention" (CE8). In the same sense, accountants also highlight the rational choice analysis of some contributors during the pandemic. For example, "a rent is accrual basis and must be billed every month, so why don't you invoice if the tenant is still living in the building (...)? Owners began to be cunning (...) and they have settled their operations according to how many taxes they want to pay considering the income level that they decide to bill" (CPA3).

Within the concept of tax compliance, besides the reporting of income, interviewees identify two situations referring to tax payment during the pandemic. On one hand, they recognize cases of taxpayers whose payment of tax obligations have not been affected by the crisis. According to CPA5, taxpayers who had the payments up to account, continued to do so, while those who had not, continued with the debt. That is, the pandemic did not modify the individual criteria. Likewise, accountants also highlight cases of entrepreneurs from much-affected sectors who have tried to comply with fiscal obligations despite the crisis: "many taxpayers make a huge effort to at least pay taxes on account" (CPA2).

On the other hand, some interviewees identify cases of a fall in tax compliance because of the attitude of taxpayers, mainly due to disagreement with the government COVID-19-related measures, and not due to lack of resources. In words of CPA8: "what the pandemic affected the most was taxpayers' attitude and feelings, they were outraged (...): ‘why will I pay taxes if they (government) do not let me open (my store)? (…) So, some taxpayers had the resources to pay, but didn't want to because they were angry."

4.2.3 EXTRAORDINARY PANDEMIC ENVIRONMENT

Interviewees point out that the most private context of operations during the pandemic is a factor that influenced informality. In this sense, the accountants explain that home delivery, rather than operations in a public sphere where invoices are issued, contributed to the increase of informality (CPA8). For instance, the entrepreneurs say: "there are many showrooms (...) that work with credit/debit card (...) but for them it is easier to avoid (fiscal) controls because they operate from a private apartment" (CE8), so possibly, according to CE5, the inspectors will not check if invoices are issued.

Moreover, the interviewees acknowledge that special state aid measures adopted in Argentina due to the pandemic crisis could have caused unintended effects on informality in two ways. First, respondents express that some registered companies may increase income underreporting to be eligible for public aid measures, originally designed for the most affected companies by the COVID-19 crisis. In this sense, the CE2 states that "the pandemic has greatly helped companies to make more disasters (...). But the billing issue is what I noticed most, that is, people who didn't want to bill to be eligible for the AWP [Work And Production Assistance program] or take a zero-rate credit." According to the accountants, some taxpayers intended to ‘adjust’ annual revenues-2020 versus 2019-to comply with the maximum income levels of these special aid programs.

Secondly, the interviewees consider that the suspensión of tax enforcement during the pandemic influenced the probability of detection and perceived penalty by taxpayers. According to CPA3, "with the pandemic everything is mixed, saying, well... if I don't issue a bill, nothing will happen." Similarly, the accountants mention that "there are no (tax) inspections ... but this will cause tax agencies to accumulate them at another time" (CPA6). This suspension of fiscal controls, besides negatively affecting the level of income reporting, also has an impact on tax compliance. In this sense, the accountants mention: "It was known that tax agencies would not carry out embargoes on this debt. So, many taxpayers have decided not to pay" (CPA8).

In other cases, considering this lack of fiscal enforcement, companies set their priorities to pay different liabilities and tax obligations were last on their list. For example, CPA3 says that "the payment of social security charges has been respected because among my clients the number one priority was to pay salaries and social charges. It is not the case with the rest of taxes, everything was left unpaid." The CPA6 shares that opinion: "in the first months (of the pandemic) the decision was: 'I pay salaries; I don't pay taxes'." In fact, some business owners indicate that they chose which taxes to pay, "what you have to pay no matter what because if you don’t the tax authority cuts your billing, it is all paid. We stopped paying some other things… "

5. Discussion

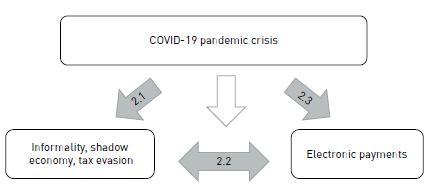

As shown in Section 2, the relationship between the COVID-19 crisis, electronic payments, and the informal economy is a complex issue. Hence, our findings reveal interesting questions that deepen the understanding of how the pandemic crisis impacted the informality of Argentinian MSMEs, as summarized in Figure 2. Regarding the behavior of partial informality during the pandemic, there are three relevant findings. First, the public health characteristics of the crisis, i.e., hygiene and blocking measures, that led to increased electronic payments resulted in higher revenues and a lower income underreporting. This negative link between the EPMs and the informality pointed out by the interviewees is consistent with the empirical macroeconomic evidence and seems to mark a pro-cyclical trend of the phenomenon (Immordino & Russo, 2018; Reimers et al., 2020; Schneider, 2010). However, it cannot be said whether there was in fact a drop in the total activity, including unreported activity (pro-cyclical behavior), or just a decrease in informality due to greater use of electronic payments.

A second important issue mentioned by the interviewees is the lower degree of fiscal control or tax interest over digital wallets compared to banking modalities. It allows the taxpayer to deal with a certain degree of informality, despite being an EPM. In this sense, during the pandemic, most entrepreneurs perceive virtual wallets as a hybrid modality between cash and banking methods that constitute an escape route to avoid formalizing operations.

The third remarkable finding is that, except for the increased use of EPMs, the other reasons mentioned by the interviewees correspond to situations of increased partial informality during the crisis. It indicates a countercyclical behavior; for example, some microenterprises underreported income to cushion the real fall in activity with the tax economy, some consumers did not ask for invoices in solidarity with the entrepreneur, who was in crisis. In addition, some companies have increased underreporting sales by taking advantage of the particularities of the extraordinary environment of the pandemic such as suspension of tax executions, transactions in private spheres, or intention to be eligible for state aid programs. The cited examples are consistent with the perceptions about the justification of informality during the periods of recessions studied by Bitzenis & Vlachos (2017) and Magessi & Antunes (2015).

Regarding unregistered companies, the findings also point out to a counter-cyclical trend. During the pandemic, in many cases, informality represented a comparative advantage for unregistered companies, as it allowed them greater flexibility in the management of fixed costs and certain benefits from the absence of tax inspections and their penalties. These situations, combined with the interviewees' perception that there is a lack of consideration on the part of the State, weaken the fiscal pact and increase the predisposition of formal entrepreneurs to act in the hidden economy, thus feeding the vicious circle of informality.

Moreover, in an underlying way, the results reinforce some informality drivers already identified in previous studies. On one hand, the mention of the tax economy and the situations illustrated in the EXTRAORDINARY PANDEMIC ENVIRONMENT section highlight the relevance of the elements of the rational choice models: the traditional exchange between costs (penalty) and benefits (tax reduction) of tax evasion, moderated by the probability of detection.

On the other hand, the divergence mentioned by accountants in relation to the attitude of taxpayers reaffirms the importance of tax morale as a factor influencing tax compliance. Regarding the tax morale of clients, the findings seem to indicate that consumers empathize with entrepreneurs in crisis and tolerate informality, which contrasts with the results presented by Alarcón-García et al. (2016) for Spain.

6. Concluding remarks

This article describes how the COVID-19 crisis affected the informality of Argentinian micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises from the perception of commercial entrepreneurs and public accountants. The study uses a microeconomic and qualitative approach with recent primary data. Unlike previous quantitative studies that identified the aggregate macroeconomic trends of the informal sector during the crisis, the findings provide insights into individual behavior that-when considered as a whole-result in increases or decreases in informality. Therefore, this article contributes to a better understanding of the phenomenon of informality from the perception of several actors. It complements and explores quantitative empirical evidence on the subject from Argentina (Pedroni et al., 2019; Pedroni et al., 2020b, Pesce et al., 2014, Villar et al., 2015a; 2015b).

Moreover, this work allows us to identify implications for public policy makers. First, considering the increase of unregistered firms mentioned by interviewees and the willingness of formal entrepreneurs to operate in the shadow economy. It seems important to design public policies that encourage participation and continuity in the formal sector. In the case of unregistered companies, a possibility could be designing voluntary disclosure alternatives, as suggested by Williams (2021) and Williams & Kayaoglu (2020).

For registered companies, it would be important to reinforce the benefits of staying in the formal sector, for example, by reducing the tax burden and employer's social security burden to mitigate the impact of overall costs. The application of severe pecuniary penalties to unregistered companies could also strengthen taxpayers' willingness to comply with tax obligations. Although, in crisis contexts, the collection of fines may be unlikely, the State's intention to sanction misconduct can positively affect the tax compliance of entrepreneurs in the formal sector.

Second, the results show the side effects of public assistance measures on informality and allow recognizing desirable lines of action to reduce income underreporting and increase tax compliance. It seems relevant to develop or strengthen tax controls on transactions made using digital wallets. It is even possible to make some changes that affect the likelihood of perceived detection by taxpayers when operating with such electronic payment methods.

In addition, other findings such as the greater propensity to underreport income due to the suspension of tax executions or the existence of a 'classification' of the payment of liabilities, also highlight the probability to detect and penalize factors that encourage informality among taxpayers. Regarding these items, the findings of Pierri et al. (2021) in Paraguay highlight the effectiveness of tax audits to fight income underreporting. Moreover, from the identification of the predominant bias, conductive financial studies suggest the development of nudges to alter undesirable behaviors, such as Castro & Scartscini (2015) in Argentina, and Mascagni et al. (2021) in Ethiopia.

The main limitation of this work is that it only includes the perception of public accountants and commercial entrepreneurs from Bahía Blanca. Another restriction derives from the type of approach. Although the qualitative nature of the work does not allow the generalization of the results, the study deepens the theme analyzed, and its findings increase the academic discussion about informality in small companies during the crisis.

In relation to the first constraint, interviews with people from other locations or other economic sectors would allow us to identify commonalities and differences and could bring new insights to the discussed issues. Likewise, for upcoming research, the same people interviewed in this study could be consulted to find out how their situation evolved.

The objective of future research is to complement the findings of the present study with a second set of qualitative data on perceived causes and consequences of informality on tax evasion. In addition, to deepen this theme in Argentina, a triangulation of sources is suggested, adding the opinion of tax experts and tax officials to the current perception of accountants and entrepreneurs.