Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista de Estudios Sociales

versión impresa ISSN 0123-885X

rev.estud.soc. no.45 Bogotá ene./abr. 2013

A Matter of Decency? Persistent Tensions in the Regulation of Domestic Service*

Manuel Abrantes

Máster en Sociología de la Universiteit van Amsterdam, Holanda. Estudiante del Doctorado en Sociología Económica y de las Organizaciones en la Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Portugal. Miembro de SOCIUS (Centro de Investigação em Sociologia Económica e das Organizações), Universidade Técnica de Lisboa. Correo electrónico: mabrantes@socius.iseg.utl.pt

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7440/res45.2013.09

ABSTRACT

The role of law in regulating and mediating social inequality has been the subject of longstanding debates. While recent research on domestic service acknowledges the importance of regulation, the legal configuration of this activity sector is seldom assessed in a detailed or critical manner. This article builds on the claim that systematic observation should be dedicated to developments in the regulation of domestic service both in the local and international contexts.. The first part of the article focuses on the advancement of law regarding domestic service in Portugal. The Domestic Workers Convention adopted by the International Labor Organization in 2011 provides a context for examining persistent constraints on change toward social recognition and equity. Difference between domestic service workers and standard wage earners is analyzed in depth, and nine unsolved practicalities of domestic service regulation in Portugal are examined in light of the recent international convention. Gender and ethnicity are identified as lingering political foundations of this employment sector. The minimal participation of domestic workers and their representatives in regulatory processes raises serious concern. The historical lens is used to clarify current particularities in the regulation of the sector.

KEY WORDS

Domestic service, law, gender, ethnicity, international Labor Organization

¿Una cuestión de decencia? Tensiones persistentes en la regulación del servicio doméstico

RESUMEN

El papel del derecho en la regulación y la mediación de la desigualdad social han suscitado amplios debates. La investigación reciente sobre el servicio doméstico reconoce la importancia de la regulación, pero la configuración legal de este sector de actividad pocas veces se analiza de manera detallada o crítica. Este artículo se basa en la convicción de que la observación debe considerar acontecimientos en distintos niveles y establecer vínculos coherentes entre las escalas nacional e internacional. La primera parte del artículo se centra en el avance de la legislación sobre servicio doméstico en Portugal. En seguida, el Convenio sobre Trabajo Doméstico adoptado por la Organización Internacional del Trabajo en 2011 ofrece un contexto privilegiado para estudiar los obstáculos que sigue enfrentando el cambio hacia el reconocimiento social y la equidad. Se presta

especial atención a la diferencia entre la población empleada en servicios domésticos y la restante población trabajadora, y nueve puntos por resolver en Portugal son examinados a la luz del reciente convenio internacional. Género y etnicidad se imponen como fundaciones políticas persistentes de este sector de empleo. La voz limitada de las trabajadoras domésticas y sus representantes en los procesos de regulación causa extrema preocupación. La perspectiva histórica ofrece una contribución importante para entender particularidades actuales en la regulación del sector.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Servicio doméstico, derecho, género, etnicidad, Organización internacional del Trabajo.

Uma questão de decência? Tensões persistentes na regulação do serviço doméstico

RESUMO

O papel do direito na regulação e na mediação da desigualdade social é um objeto de debate já clássico. Embora a investigação mais recente sobre serviço doméstico reconheça com frequência a importância do enquadramento legal, este enquadramento tem sido poucas vezes examinado de forma detalhada ou crítica. O presente artigo assenta na noção de que importa empreender uma análise sistemática dos passos dados na regulação do serviço doméstico, tanto em contexto local como em contexto internacional. A primeira parte do artigo debruça-se sobre o desenvolvimento da legislação laboral deste setor de emprego em Portugal. A Convenção sobre Trabalho Doméstico adotada pela Organização Internacional do Trabalho em 2011 oferece um momento privilegiado para examinar os constrangimentos que continuam a colocar-se em matéria de reconhecimento social e equidade. Presta-se particular atenção às diferenças persistentes entre a regulação aplicável a trabalhadoras/es domésticas/os e a regulação geral do trabalho assalariado, e um conjunto de nove questões por resolver é examinado à luz da recente convenção internacional. O gênero e a etnicidade emergem como alicerces políticos deste setor de emprego. A participação reduzida de trabalhadoras/es domésticas/os e de organizações que as representem no processo regulatório suscita especial preocupação. A perspetiva histórica revela-se útil para clarificar singularidades da regulação atual do setor.

PALAVRAS CHAVE

Serviço doméstico, direito, gênero, etnicidade, Organização internacional do Trabalho.

I n June 2011, the International Labor Organization (ILO) adopted a convention concerning domestic workers. This offered a privileged moment to examine historical developments and lingering constraints on change toward social recognition and equity. Recent research has paid considerable attention to the global and local dynamics of domestic labor. While the importance of laws on the working and living conditions of domestic workers is a recurrent claim in such research, the legal configuration of this activity sector is seldom assessed in a detailed or critical manner. Analysis is frequently confined to the most recent reforms. As a result, the important contribution of historical research is confronted with the unclear position of domestic labor between household and labor dynamics.

This article addresses advancements in the regulation of domestic service at both national and international levels, focusing on the contexts of Portugal and the ILO. Analysis is primarily based on the documental analysis of institutional materials. Valuable insights have been drawn from open-ended interviews with domestic workers, labor and employer representatives, and local activists. This article begins by bringing together a handful of theoretical contributions that help in the understanding of lawmaking as a sociopolitical negotiation. It then focuses on the empirical examination of developments in the regulation of domestic service in Portugal. It draws as far back as the implementation of the Civil Code of 1867 to grasp the transformation in rights and meanings. The third section of the article discusses the laws currently in place and the implications of the recent international convention on domestic workers. A lingering question is to what extent exceptional legislation on particular employment sectors responds to their structural singularities, or, on the contrary, excludes them from general mobilization and the accomplishments of the working class.

Drops in freedom, care chains, and globalization

The role of law in regulating and mediating social inequality has been the subject of longstanding debates. The work of Karl Marx is particularly sensitive to norms on the minimum age of workers, daily working hours, and land expropriation, describing their establishment in a polity dominated by capitalist agents in which the elected parliament at best administers "freedom drop by drop" (Marx 2010, 183). Research on contemporary dynamics of domestic service exposes the tenacity of some elements in this view. Despite notable achievements, underage labor is still a key problem to be addressed (ILO 2010). Daily working hours remain a major controversy both in lawmaking and in everyday practice, especially for live-in domestic workers, and growing transnational dynamics are far from making a radical leap toward freedom or interethnic solidarity (Anderson 2000; Parreñas 2001; Sassen 2007; Lutz 2008; Canevaro 2009).

In this sense, paid domestic labor offers a strategic site to examine the ambiguous process through which state law draws its legitimacy from an outspoken opposition to traditional power inequality based on social status ("all are equal before the law"), while it legitimates difference and prejudice inherited from that very same source of power. The historical closeness between domestic labor and serfdom, to begin with, revives the classic questioning of the construction of wage labor as opposed to slavery (Weber 1978). Comparative historical research documents tensions in the position of domestic service between a life-stage occupation and a lifelong occupation following the dawn of industrial societies (Fauve-Chamoux and Wall 2005). Shifts toward a greater degree of commodification require both the acknowledgment of domestic service as an occupation and the break with specific forms of paternalism permeating it. Beyond changes in the volume of domestic service over time, changes in a work process are at stake (Sager 2007). The potential of lawmaking to mold the complex nexus of commodification and social denigration of the occupation cannot be underestimated (Cooper 2005).

According to Pierre Guibentif (2009), two key legislative enterprises played a leading role in the consolidation of modern capitalism: constitutionalism and codification.

Civil codes adopted in several states of Western Europe following France in 1804 are especially important, insofar as they were created upon principles of positivistic policy, professional technicality, and national interest (Weber 1978). The historian Antônio Manuel Hespanha (2003) corroborates that the production of civil and other codes is nothing short of a landmark in the transition from common law into rationalist law, and therefore, in the advent of liberalism. He argues that there is a significant ambivalence in this endeavor. While it promotes the sys-tematization and understanding of the law among citizens, thereby favoring popular control over it, it is also grounded in the notion of a "juridical monument" aiming to be as permanent and consensual as possible, that is, to resist parliamentary action. In her examination of the first civil code in Portugal adopted in 1867, Teresa Beleza (2002) emphasizes its role in legitimating patriarchal rule. Women were granted an indirect relationship to the state mediated by their fathers, husbands, or older sons. She also stresses that legislation does not merely adjust to existing social inequality in a given historical moment; rather, it builds and shapes inequality. The study of legislation, which has been modified in later periods, is therefore key to understanding today's juridical discourse and practice (Beleza 2000).

The consideration of gender asymmetry has relevant implications for the subject under analysis. Historical research exposes significant links between the commod-ification of labor under capitalist industrialization and the ideology of separate spheres of production and reproduction, which prescribed the public agency of men and the invisible domesticity of women (Braudel 1969; Pinto 2007). Activities understood as domestic work have been largely "coded as feminine" (McDowell 2000, 506).1 It is noteworthy that the gender distribution of paid household labor was more balanced in the past, although segmentation was apparent in the predominance of men in the most prestigious positions (Sarti 2005). This does not mean that the underprivileged position of domestic workers in labor law is unrelated to its extensive feminization; rather, the opposite is true. Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Russell Hochschild address recent developments as they refer to the "new emotional imperialism" (Ehrenreich and Russell 2002, 27). They focus on the international migration system of care labor, which has recently emerged as Western societies demand low wage workers, overwhelmingly women, to look after children and frail adults. Through the money they earn abroad, migrant women often support families and communities back home, in particular their own children and elderly relatives. The elaboration on global care chains and emotional labor thus notably frames domestic service within the dynamics of contemporary capitalism and globalization rather than traditional society.

Portugal has registered a rapid increase in immigration since the mid-1970s and severe ethnic segmentation in the labor market (Baganha 1998; Gôis and Marques 2009; Casaca and Peixoto 2010). The concentration of immigrant women in domestic service illustrates how newly arrived ethnic minorities occupy jobs abandoned by local workers due to their negative social standing. An extensive private demand for childcare and eldercare underpins the latest upsurge of domestic service (Guerreiro 2000; Wall and Nunes 2010). A recent survey on paid domestic workers in this country shows that violations of legal rights by employers abound, especially concerning social security contributions, holiday pay and benefits, concession of maternity leave, and payment of health costs in case of workplace accidents (Guibentif 2011). A large fraction of domestic service remains in the informal sector. In addition, the relative novelty of democratic politics in Portugal, where an authoritarian regime was in office from 1928 to 1974, suggests affinity with developments in other countries in Southern Europe and Latin America (Valenzuela and Mora 2009; Goldsmit et al. 2010). Although legal reforms have been pursued to approximate domestic service to general wage labor standards, the resilience of exceptional treatment and limited legal compliance remains at the forefront of concerns regarding domestic service.

While national politics are criticized for being too distant from citizens to allow full democratic participation, supranational authorities with different purposes have emerged as key sites in the readjustment of power (Hespanha 2003; Sassen 2007). Alain Supiot (2006) highlights the normative political orientations followed by organizations such as the European Union or the World Bank, which promote an uncritical understanding of adaptable labor markets as the desirable or only possible future. In contrast, the ILO has recognized the need to combine market liberalization and regulation since its creation in 1919. Denouncing abuse in under-regulated employment sectors remains a political trademark of this organization, and it played a significant role in the process leading to the adoption of the Domestic Workers Convention in 2011 (ILO 2010).

Effective regulation on paid domestic labor has been troubled by "variation between countries and variation between economic sectors in the same country in terms of what is socially and legally constructed as acceptable employment practice" (Anderson 2006, 25). The overarching perspective of Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2006) on globalization offers an important contribution to framing the subject at hand. In the author's view, there are two distinct spheres of production. The hegemonic camp pushes for neoliberal economy, weak state, liberal democracy with an absolute priority of civic and political rights over social and economic rights, and the primacy of the rule of law and the judicial system conceived as independent and universal mechanisms. On the other hand, the counter-hegemonic or subordinate production of globalization builds on "the aspiration by oppressed groups to organize their resistance on the same scale and through the same type of coalitions used by the oppressors to victimize them, that is, the global scale and local/global coalitions" (Santos 2006, 398). Examining the struggle for the rights of migrant domestic workers within two nongovernmental organizations in the United Kingdom, Bridget Anderson (2010) shows how radical undertakings can be captured gradually by the logic and practices of state sovereignty. Based on research in the Netherlands, Sarah van Walsum (2011) shows how the regulation of migrant domestic work challenges stationary views on the public-private divide, the limits of the labor contract, and the borders of the nation-state. These authors favor a notion of regularization and legalization of work not as ends in themselves, but as means to strengthenor else weakenthe position of the workers at stake.

Exclusion and approximation (1867-2012)

Consisting of a total of 2,497 articles, the Portuguese Civil Code of 1867 covers a broad range of subjects including citizenship rights and duties, ownership, family, trade, and employment. One particular chapter concerns the regulation of labor. This chapter is divided into eight sections, the first one of which is limited to the provision of domestic service. Domestic service, like liberal professions and apprenticeship arrangements, is separated from standard wage labor, which is dealt with in a section of its own applying to all occupations without specific regulation.

The focus of legislators on paid domestic labor suggests an acknowledgment of this issue not only as complex or delicate, but also as a matter of public order. The civil code establishes that domestic service can only be considered as such if it is rewarded and performed on a temporary basis. Any commitment for life is deemed invalid for legal purposes, which means both parties are free to abandon it without any cost or obligation. Interestingly, this provision is not attached to any other occupation in the Civil Code of 1867, and one of its clear goals is to distinguish domestic service from serfdom or slavery (Ferreira 1870). Further rules regarding the beginning and end of the labor relationship, as well as the set of duties and rights of both parties, are specified. The selection of words is noteworthy. The person who purchases domestic services is referred to as amo (master), whereas in the section of the civil code concerning standard wage labor, the word servido (served person) is used instead. The person who is recruited to work is called serviçal (servant) in both sections. This detail is interesting because it reflects a distinction not between domestic workers and regular wage earners, but between employers. This is a distinction in nature: the masternot the employermay own more than the worker's labor. What employers buy from domestic workers, Anderson (2000) argues, may be their very personhood more than their labor power, thus challenging the postulate of modern political philosophy that all individuals possess their own body and minda key element in the achievement of rights for women and ethnic minorities throughout the twentieth century.

The Civil Code of 1867 also states that whenever domestic servants have not been recruited to perform a particular task, the labor relationship binds them to perform any service compatible with their physical ability. Local customs are mentioned in several articles as providing acceptable standards. While this is not particular to legislation on domestic service, it does add some peculiar elements to it. For instance, the civil code states that in the absence of an explicit agreement on remuneration, pay shall be based on local customs considering the servant's sex, age, and duty. If the servant suffers from a health problem, the master is responsible for arranging medical support and deducting its costs from the remuneration, if the master is not willing to pay for it out of "generosity" (Civil Code 1867, Art. 1384/3). Regarding inheritances, in case the master decides to leave some of his inheritance to a servant, this must not be deducted from the remuneration and dismissal compensation (15 extra days) that the master's heirs are bound to pay the servant. Concerning age, minors are allowed to perform domestic services, although in that case an agreement must be reached between the master and the minor's legal guardian. Among the employer's duties, it is stated that if the servant is underage, the master is obliged to correct his or her mistakes "as a legal guardian would" (Civil Code 1867, Art. 1384/1).

This piece of legislation offers two distinct contributions. First, it attempts to acknowledge some rights and benefits in domestic service. Second, it clearly asserts the singularity of domestic service within existing occupations and the paternalistic characteristics of this type of labor relationship. The troubled disentanglement between paid labor on the basis of an employment contract and unpaid labor on the basis of family obligations is especially apparent. Besides the aforementioned selection of words, the duties of the "master" and his authority to command go well beyond the regulation on standard wage labor. Such development is closely related to the legal construction of the inviolability of the home, which owes less to modern day constitutional rights on individual freedom and privacy than to the autonomy of the domestic sphereas a peripheral powertoward the central power of the state (Hespanha 2003, 22). In fact, individual rights are often sacrificed within the very context of the patriarchal household. It is necessary to point out that the protection of domestic workers in the Civil Code of 1867 is minimal, as just causes for dismissal include broadly applicable notions of inability to work, bad behavior, and breaking or stealing the master's belongings. This source of employment insecurity, as shown later on in this article, remains in place until today, and is important in maintaining asymmetry in the relationship between workers and their employers.

Since the last decades of the nineteenth century, a wide array of legislation on labor issues has been adopted in Portugal. This includes the condition of minors and women as workers, the rights of workers to association and representation, the responsibility of employers regarding health and safety at work, the legal procedures to deal with disagreements between employers and workers, and the regulation of labor inspection. Some of these decrees contained an article excluding particular categories of workers, most often those employed in agricultural, maritime or domestic services. The underlying claim was, and still is, that the special conditions in which these occupations are performed warrant exceptional regulation. Labor inspection conflicts with the ambiguous notion of the inviolability of private households (Anderson 2010). A second problem is that domestic workers are required to work, or stay in the workplace, longer than standard wage earners. Notably, when the maximum number of working hours was established in Portugal in 1919 (8 hours per day and 48 hours per week, at that time), the decree explicitly mentioned that it did not apply to rural workers, hotel and restaurant workers, and domestic servants (Decree No. 5516, May 10, 1919).2

Introduced by an authoritarian government, the general labor law of 1933 (Estatuto do Trabalho Nacional, Law-Decree 23048, 23 September, 1933) imposed dramatic changes on the system of industrial relations. Collective organization was severely restricted; among other things, workers and companies were required to maintain a "social peace spirit" and forbidden to "suspend or disturb" any economic activity "with the purpose of getting different working conditions or other benefits." The law on the standard rules for employment contracts in 1937 added important provisions (Law No. 1952, March 10, 1937). By the time the civil code was revised in 1966, provisions on employment were limited to the definition of basic concepts, all further issues being dispatched to specific labor legislation. Absent from both the new civil code and standard labor law, domestic service was still regulated by the Civil Code of 1867.

The fall of the dictatorship in 1974 opened new possibilities for collective action and bargaining. Domestic service, however, was not to be merged into general labor law. When a minimum monthly wage was introduced in 1974, agricultural and domestic workers were again excluded. A minimum wage for domestic workers was only implemented in 1978. This value was increased several times in the following two decades, although it would remain below the general minimum wage until 2004 when they were finally merged.3

A law on domestic service was finally adopted in 1980. It resulted from the initiative of a recently created domestic service workers' union. While this initiative was acknowledged as a legitimate claim, the law was introduced by a governmental decree under the protest of competing parties that demanded a wider debate in parliament and due consultation with labor representatives. The main criticisms about the document concerned the excessive number of maximum working hours, the weekly period of rest and holiday allowances below standard labor law, and the inaccurate definitions of domestic work.4

Table 1.

The very preamble of the decree is dubious as it states that it is "an imperative of social justice to cover the activity sector of domestic services with updated and more complete, though necessarily specific, legislation." Its 24 articles cover the various possible arrangements between employer and worker regarding time, holidays and remuneration, the valid procedures to begin and terminate the labor relationship, and the minimum age of workers. The decree has three distinct aspects. First, not only is the domestic workers' minimum wage set separately from and below the standard minimum wage, but the provision of housing and food by the employer can also comprise a part of the remuneration. Second, there is no fixed maximum working time. Live-in workers are entitled to rest and eating breaks of at least two hours per day, and are entitled to rest at night for eight consecutive hours. These breaks from work "are granted without detriment to the tasks of oversight or assistance to the household," and the night rest "should not be interrupted except for serious non-regular or imperative reasons." Last, valid reasons for both parties to terminate the labor relationship include a significant change in the conditions that motivated the relationship, failure to fulfill the basic duties established in the same law, breach of confidentiality over sensitive matters, and lack of good manners. The employer is also entitled to terminate the relationship if the worker brings other people such as relatives or friends into the house without the employer's knowledge, maintains habits or behaviors that do not suit the regular operation of the household, or carelessly uses equipment owned by the employer.

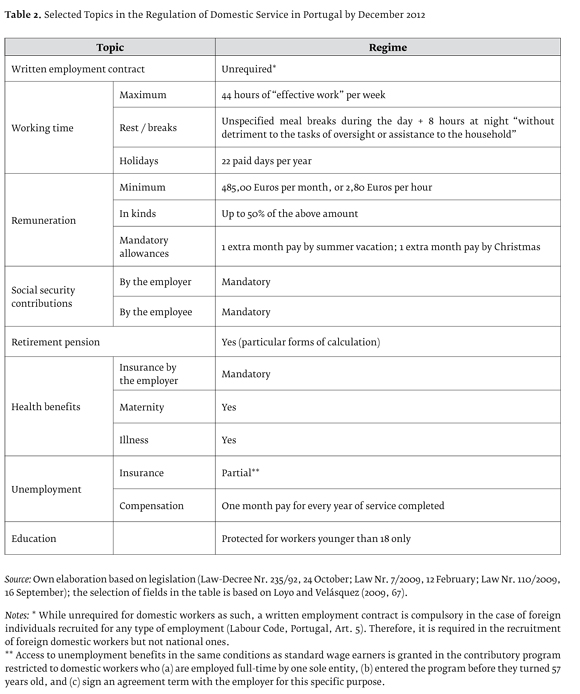

The law on domestic service was revised in 1992, resulting in the version currently in force (Table 2). A number of important changes were introduced. To start with, the article on working time was substantially modified. For the first time, it was established that the "normal period of weekly work" for domestic workers must not exceed 44 hours. In the case of domestic workers who reside in the employer's premises, however, this maximum number of hours refers to time spent in "effective work." Sufficient room is left for live-in domestic workers to be available 24 hours per day as there is no specific definition of effective work. For instance, it is unclear whether surveillance tasks are considered effective work. If surveillance tasks are not considered effective work, it is unclear whether the worker is free to exit the house and return only when the next period of effective work begins. Both institutional documents and policymakers remained unanimously elliptical in this respect.

Three additional issues were introduced in 1992. First, the domestic service law mandated that the Christmas allowance to which domestic workers are entitled should not be below 50% of their monthly pay. However, a general law on the Christmas allowance was adopted in 1996, mandating that all workers, including domestic workers, are entitled to an allowance of 100% of their monthly pay, to be paid until the 15th of December every year. Second, a complete list of rules on health and safety at the workplace was incorporated. These include the employer's duty to inform the worker about the operation of equipment and maintenance products used in the household, to repair damaged or dangerous materials, and, in the case of in-house domestic workers, to provide housing and food in conditions that are not harmful to the worker's health and hygiene. More important, the employer must obtain insurance from a company or organization legally entitled to do so, to cover any damage resulting from accidents at work. After legislation was approved at the European Union level, more complete legislation on accidents and illness at work was adopted covering all workers, including those employed in domestic service. Third, an article defining what constitutes abandonment of the labor relationship by the worker and what procedures must be followed in that case was introduced.

Although a national labor code eventually came into force in 2003, domestic service is still regulated by the law on domestic service. This is also true for economic activities such as entertainment, navy and harbors, railway transportation, agriculture, sports, and public administration. The current legal configuration retains the distinction between domestic service and standard wage labor made in the Civil Code of 1867, while a gradual advancement in rights has taken place.

Table 2.

Unsolved practicalities and the international convention

Following the guidelines of the ILO's double discussion procedure, final versions of the Domestic Workers Convention and Recommendation were adopted in 2011 (ILO 2011a, 2011b). Since then, a trade union confederation and several nongovernmental organizations representing women and migrants in Portugal have urged the government to take action toward ratifying the convention. One of their claims is that national regulation is in agreement with the standards set in the convention; therefore, ratification shall not require any legislative innovation. This may be understood as a strategic step to depoliticize and thereby ease the ratification.

A thoughtful observation of the convention requires addressing various unsolved practicalities in the regulation of paid domestic labor in Portugal. Far from being negligible, these issues may be too significant to be dealt with as simple administrative adjustments. For the purpose of clarity, they can be organized into nine distinct yet interrelated matters.

Social protection. The access of domestic workers to social protection remains regulated by a special scheme. Workers who are employed full-time by one sole entity on a monthly basis are in a different situation than workers under part-time arrangements. The former are able to enroll in two distinct programs: 1) a program with the same rules and benefits that apply to standard wage earners, including unemployment benefits; and 2) a program based on a lower tributary rate (28.3% against 34.75%, at the time of writing) and a standard remuneration that can be below the worker's actual pay. The latter has been implemented with a pecuniary protective aim, as a portion of the pay is not taxed by social security. The first significant distinction is that workers under part-time arrangements can only access program 2. Even among workers who are employed full-time by one sole entity, enrollment in program 1 is only accessible if they are under 57 years old and if they sign an agreement term with their employer for this particular purpose. Considering that the National Constitution (Art. 59/1b) includes the right of all workers to "material assistance when they are involuntarily in unemployment," there seems to be an odd variety of caveats in the case of domestic workers. Although this article of the Constitution prohibits discrimination based on age, sex, race (ethnicity), citizenship, place of origin, religion, and political or ideological conviction, it does not mention occupation. Encased in a lower level of benefits, domestic workers can be described as sub-workers in the social security system. In the meantime, Article 14 of the ILO Domestic Workers Convention is not without ambig-uousness itself as it requires states to "ensure that domestic workers enjoy conditions that are not less favourable than those applicable to workers generally in respect of social security protection", although measures to that end may be "applied progressively" and "with due regard for the specific characteristics of domestic work". Still, it is increasingly difficult to argue from either a critical or a normative perspective that the specific characteristics of domestic work justify social protection below general standards in the labour market.

Indistinction between live-in and live-out domestic workers. The law examined earlier applies to both live-in and live-out domestic workers, resorting to the concept of "effective work" and the underlying fiction that live-in domestic workers perform it for a maximum of 44 hours per week, to cover up the large gray area of negotiation between employer and worker. Article 10 in the international convention refers to periods during which workers "are not free to dispose of their time as they please and remain at the disposal of the household in order to respond to possible calls," a notion that is absent from national law. Indistinction between live-in and live-out workers therefore translates into the underprivileged situation of the former, as they remain legally vulnerable to the imposition of overtime.

Dismissal. The pursuit of fair terms of employment requires a reconsideration of the norms that regulate the termination of the relationship. Just cause for dismissal by the employer is defined in a manner that is both broad and detailed. It comprises disobedience, lack of interest, mishandling of material items or confidential matters, abnormal reduction in productivity, lack of good manners, and behaving in a way that does not suit the regular operation of the household, among other things. Though more limited, just cause for dismissal by the worker also includes some of these considerations, including the ones on behavior. The relationship can also be terminated due to the employer's inability to maintain it, economic insufficiency, or substantial transformation in the circumstances under which the worker was recruited. While the convention does not elaborate on this topic, it is plausible that all measures aiming to reduce workers' vulnerability depend on addressing and reformulating the terms of employment termination.

Written contracts. Article 7 of the convention states that measures shall be taken to ensure that "domestic workers are informed of their terms and conditions of employment in an appropriate, verifiable and easily understandable manner and preferably, where possible, through written contracts." Although absent from the law on domestic service in Portugal, written contracts are deemed compulsory in the general labor code if the relationship involves foreign workers, short-term employment, part-time employment, intermittent employment, or temporary employment. The fact that a contract of employment with full legal rights is presumed to be in place whenever a contract has not been signed may explain why this is not a common claim made by national labor unions at the moment. However, the wide legal scope for unilateral decision by the employer of a domestic worker exposed to the three issues discussed earlier throws a different light on the subject. The value of written contracts has been highlighted in one of the latest campaigns developed in Portugal for the rights of domestic workers, in a joint initiative by activists and scholars. The general informative brochure for domestic workers and employers produced by this campaign even includes a template for written contracts (GAMI 2012).

Education. Since the first version of the law adopted in 1980, domestic workers in Portugal have been required to be at least 16 years old. Education is not mentioned in the law. However, the labor code comprises a number of provisions protecting workers under the age of 18, including one on education; these apply to domestic workers as well. Aside from several provisions against child labor, the international convention requires ratifying member states to ensure that employers of domestic workers under the age of 18 do not "deprive them of compulsory education, or interfere with opportunities to participate in further education or vocational training" (Art. 4). It is crucial to address the domestic workers' right to education and attendance of courses considering present day compulsory schooling, which includes workers above 18. The importance of this issue is underlined by the lower level of schooling of many women employed in domestic service, especially natives (Guibentif 2011). Several countries in Latin America have exemplary protective clauses in this regard (Loyo and Velásquez 2009).

Living conditions for live-in domestic workers.

The insufficient acknowledgment of live-in domestic workers in national law translates into the absence of objective standards for their living conditions. The only requirement is that housing and food must be provided "in conditions that safeguard the hygiene and health of workers." This is all the more problematic as general provisions on housing provided by employers to standard wage earners, such as posted or temporarily delocalized workers, tend to be equally laconic. The contribution of the convention is not straightforward either. While its reference to "decent living conditions" maintains the subject in the muddy waters of customs, the notion of "respect" for "privacy" mentioned in Article 6 may be a more fruitful ground for collective parties to build their claims.

Freedom. Article 9 of the convention protects the freedom of domestic workers to reach an agreement with their employer on whether to reside in the household, to be away from the house and household members during periods of daily, weekly, or annual leave, and to keep in their possession travel and identity documents. Clearly intertwined with some of the points discussed earlier, these three provisions are absent from the law on domestic service employment in Portugal. If this sector is to be maintained under particular regulation, such regulation should address the objective sources of vulnerability that public intervention and academic research have repeatedly uncovered. This article of the convention is especially relevant because basic human rights in the employment context are often taboo in political debate; it is presumed that both parties comply with them and all workers know about them. The fact that authoritative documents such as the National Constitution assert or implicitly require respect for these rights means that labor legislation does not need to be concerned with them. Yet this produces practical results only insofar as the concrete manifestations of such rights in particular contexts are recognized and protected.

Intermediation. Two distinct matters arise under intermediation. First, trafficking or smuggling of people is to be restrained. Again, provisions and measures are left outside the realm of domestic employment regulation, since migration and criminal laws are expected to deal with this issue, even if domestic service bears close historical links to forced labor. Far from being a matter of the past, these links have suffered new impulses under globalizing neoliberalism (Ehrenreich and Russell 2002; Peixoto 2009). Second, intermediation can also refer to lawful private companies that provide domestic services. Intervention in this regard is not only about ensuring compliance with basic human rights, but also about defining the conditions under which private agencies that recruit or place domestic workers operate. A major risk is that workers employed through agencies are not covered by either domestic service employment law or general labor law, as they become subcontracted service providers, or self-employed workers, following one of the most typical routes to precariousness in contemporary labor markets. This configuration is possible, though illegal, as independent work requires a degree of freedom and autonomy that domestic workers hardly enjoy. It is more properly understood as a way to circumvent employment rights and standards. Nevertheless, it may prosper unless domestic service regulation addresses it in proper terms.

Labor inspection. The statutes of labor inspection in Portugal explicitly state that, whenever the workplace is a private residence, the rules of domiciliary visit set through penal regulation apply (Law-Decree 102/2000, June 2, 2000). This means a warrant for that purpose must be obtained from judicial authority. The "private workplace" is hereby protected. There is a further difficulty in the case of domestic workers. As they are often sole employees, the intervention of labor inspection is likely to contribute to the deterioration of their relationship with the employer. Although this problem in labor relations is not limited to domestic service, the vulnerability of certain employment sectors demands an explicit and straightforward strategy.

Conclusion

To a large extent, these nine unsolved practicalities represent the distance that still separatesalbeit to a lesser degree than in 1867domestic service from general labor law. Some of these issues can only be addressed if their roles in structuring paid domestic labor are explicitly acknowledged. Dismissal procedures and the case of live-in domestic workers are the most critical matters; addressing them may lead to a dramatic readjustment of power in this activity sector, and progressive propositions are bound to be accused of prompting unemployment and disfavoring domestic workers for their excessive aspirations. In addition, the enactment of full rights to social security and labor inspection requires changes in neighboring legal provisions, pushing the struggle beyond the law on domestic service employment. While the historical approach offers important contributions in clarifying particularities in the regulation of the sector, further study is required to examine relevant links with regulation in areas such as migration and gender equality (Va-lenzuela and Mora 2009, 294-7).

An additional issue concerns the recent changes in general law. As employment rights are pressed for reduction under neoliberal responses to economic recession (Supiot 2010), approximation may be accomplished less by the inclusion of domestic workers under labor standards of the overall workforce than by the reduction of those labor standards. This discussion echoes Ulrich Beck's (2000) claim of the process of "Brazilianization" of the West. He argues that, despite the general notion that Europe is setting the standards for the other parts of the world, the opposite may be taking place in the sphere of employment. Based on the historical examination in this article, one may wonder if, despite the general notion that standard wage labor is setting the standards for domestic service employment, a "domestic-workifi-cation" of the labor market is actually underway. At the same time, the market dynamics are likely to maintain considerable pressure to exclude domestic workers from the regulation in place, especially through the legal configuration and rhetoric of the self-employed worker.

A notable feature in the examined regulatory processes is that domestic workers and their representatives have been absent from them. Looking into the mid-twentieth century, Inês Brasão (2012) shows how the ethics of domestic service in Portugal have been historically and socially constructed by masters or employers. The analysis in this article suggests that the same assertion can be extended to cover the implementation of the Civil Code of 1867, and more surprisingly, the period following the implementation of democracy in the 1970s. New social tensions regarding the paternalistic foundations of this type of labor relationship and acts of disorganized resistance from domestic workers were accompanied by reluctant legal advancements. From an historical point of view, the juridical condition of domestic workers exposes their slippery position between paid labor on the basis of an employment contract and unpaid labor on the basis of gender, class and ethnic roles. Considering research in other locations, this study corroborates the notion of heterogeneity across countries and a common disadvantage of domestic service workers vis-à-vis the local legal framework applying to standard wage earners (ILO 2010; Loyo and Velásquez 2009).

The recent international convention is a significant tool to contest the underprivileged position of domestic workers in labor regulation. Domestic workers are now incorporated into the ILO's broader agenda for decent work. Yet, a distinct sort of decency remains at stake one that is markedly evident in legal documents from earlier days. It is closely linked to public order, to social values and customs, and to the implicit indecency of "lower level" citizens and workers claiming for equality. It is still, in the end, a matter of decency.

Comentarios

* This article stems from the PhD research project "Domestic services and migrant workers: The negotiation of the employment relationship", conducted in 2010-2013 at the Technical University of Lisbon. A draft version was discussed at the International Conference on Law and Inequalities, University of Coimbra, April 23-24, 2012. I thank all of the interviewees, experts, technical staff and fellow researchers who offered their time and energy at some point. I am especially grateful to Sarah van Walsum, Sara Falcão Casaca, and the anonymous reviewers at Revista de Estudios Sociales for precious comments. This work is supported by the FCT - Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (research grant SFRH/BD/61181/2009).

1 The verb to code in McDowell's formulation naturally takes on a different meaning than above, as it refers to common sense and everyday practice rather than legal regulation. However, the fact that the same word is used is an interesting detail.

2 That same year, the ILO was created within the League of Nations; Portugal was among its founding member states. This was a period of intense labor mobilization. In 1921, a regional association of hotel and private household domestic workers was created in Lisbon. Though supported by local proletarian trade unions, it was only able to obtain permission from state authority to operate in 1939, after domestic workers had been excluded from it.

3 In 1978, the minimum monthly wage for domestic workers was 3,500 Escudos per month (gross) (17.46 Euros), against 5,700 Escudos (28.43 Euros) for standard workers (simple unweighted conversion). By 2004, the minimum wage was 365.60 Euros per month; by 2012, it was 485.00 Euros per month.

4 The process leading up to the adoption of legislation can be followed in Diário da Assembléia da República, 1' Série, 11/03/1977: 2830; 29/10/1977: 38; 16/06/1978: 3283; 21-06-1980: 3122; and Diário da Assembleia da República, 2' Série-A, 16/06/1978: 914. For the discussion of the law eventually approved in parliament, see Diário da Assembleia da República, 1' Série, 31-01-1981: 855-866; 06/02/1981: 935-944; and 11/02/1981: 966-978.

References

1. Anderson, Bridget. 2000. Doing the Dirty Work? The Global Politics of Domestic Labour. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

2. Anderson, Bridget. 2006. A very Private Business: Migration and Domestic Work. Working Paper of COMPAS - Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, 28. Oxford: University of Oxford. [ Links ]

3. Anderson, Bridget. 2010. Mobilizing Migrants, Making Citizens: Migrant Domestic Workers as Political Agents. Ethnic and Racial Studies 33, no. 1: 60-74. [ Links ]

4. Baganha, Maria Ioannis. 1998. Immigrant Involvement in the Informal Economy: The Portuguese Case. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 24, no. 2: 367-385. [ Links ]

5. Beck, Ulrich. 2000. The Brave New World ofWork. New York: Polity Press. [ Links ]

6. Beleza, Teresa. 2000. Género e direito: da igualdade ao "direito das mulheres". Themis 1, no. 2: 35-66. [ Links ]

7. Beleza, Teresa. 2002. "Clitemnestra por uma noite": a condição jurídica das mulheres portuguesas no século XX. In Panorama da cultura portuguesa no século XX, Vol.I, ed. Fernando Pernes, 121-150. Oporto: Fundação Serralves. [ Links ]

8. Brasão, Inês. 2012. O tempo das criadas: a condição servil em Portugal (1940-1970). Lisboa: Tinta da China. [ Links ]

9. Braudel, Fernand. 1969. Écritssurlhistoire. Paris: Flammarion. [ Links ]

10. Canevaro, Santiago. 2009. Empleadas domésticas y empleadoras en la configuración del trabajo doméstico en la Ciudad de Buenos Aires: entre la administración del tiempo, la organización del espacio y la gestión de las "maneras de hacer". Campos 10, no. 1: 63-86. [ Links ]

11. Casaca, Sara Falcão and João Peixoto. 2010. Flessibilità e segmentazione del mercato del lavoro in Portogallo: genere e immigrazione. Sociologia del Lavoro 117: 116-133. [ Links ]

12. Cooper, Sheila McIsaac. 2005. Service to Servitude? The Decline and Demise of Life-cycle Service in England. The History of the Family 10, no. 4: 367-386. [ Links ]

13. Ehrenreich, Barbara and Arlie Russell eds. 2002. Global Woman. Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy. New York: Owl Books. [ Links ]

14. Fauve-Chamoux, Antoinette and Richard Wall. 2005. Domestic Servants in Comparative Perspective. The History of the Family 10, no. 4: 345-354. [ Links ]

15. Ferreira, José Dias. 1870. Código civil portuguezannotado, Vol. III. Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional. [ Links ]

16. GAMI - Grupo de Apoio às Mulheres Imigrantes. 2012. Direitos e deveres no trabalho doméstico. Lisbon: GAMI. [ Links ]

17. Goldsmit Connelly, Mary Rosaria, Rosario Baptista, Ariel Ferrari and María Celia Vence (Coords.). 2010. Hacia un fortalecimiento de derechos laborales en el trabajo de hogar: algunas experiencias de América Latina. Montevideo: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. [ Links ]

18. Góis, Pedro and José Carlos Marques. 2009. Portugal as a Semi-peripheral Country in the Global Migration System. International Migration 47, no. 3: 21-50. [ Links ]

19. Guerreiro, Maria das Dores. 2000. Employment, Family and Community Activities: A New Balance for Women and Men. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2000/112/en/1/ef00112en.pdf (retrieved 11 June 2012). [ Links ]

20. Guibentif, Pierre. 2009. Teorias sociológicas comparadas e aplicadas. Bourdieu, Foucault, Habermas e Luhmann face ao direito. Novatio Iuris 3: 9-33. [ Links ]

21. Guibentif, Pierre. 2011. Rights Perceived and Practiced: Results of a Survey Carried out in Portugal as Part of the Project "Domestic work and domestic workers: interdisciplinary and comparative perspectives". Working Paper of Dinamia'CETTUL: Centre for Socioeconomic Change and Territorial Studies, 2011/01, ISCTE. Lisbon: Lisbon University Institute. [ Links ]

22. Hespanha, Antônio Manuel. 2003. Cultura jurídica europeia. Síntese de um milênio. Mem Martins: Publicações Europa-América. [ Links ]

23. International Labour Office (ILO). 2011a. Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (C189). ILO, http://www.ilo.org/ dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_ CODE:C189 (retrieved 9 October 2012) [ Links ]

24. International Labour Office (ILO). 2011b. Domestic Workers Recommendation, 2011 (R201). ILO, http://www.ilo.org/ dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_IN-STRUMENT_ID:2551502 (retrieved 9 October 2012). [ Links ]

25. International Labour Office (ILO). 2010. Decent work for domestic workers, report IV(i), International Labour Conference, 99th session. Geneva: ILO. [ Links ]

26. Loyo, María Gabriela and Mario D. Velásquez. 2009. Aspectos jurídicos y económicos del trabajo doméstico remunerado en América Latina. In Trabajo doméstico: un largo camino hacia el trabajo decente, eds. María Elena Valenzuela and Claudia Mora, 21-70. Santiago: ILO. [ Links ]

27. Lutz, Helma (Ed.). 2008. Migration and domestic work: a European perspective on a global theme. Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

28. Marx, Karl. 2010 [1867]. Capital. A Critique ofPolitical Economy, Vol. I. Moscow: Progress Publishers. [ Links ]

29. McDowell, Linda. 2000. Feminists rethink the economic: the economics of gender / the gender of economics. In The Oxford handbook of economic geography, eds. Gordon Clark, Maryann Feldman and Meric Gertler, 497-517. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

30. Parreñas, Rhacel Salazar. 2001. Servants of Globalization. Women, Migration, and Domestic Work. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

31. Peixoto, João. 2009. New migrations in Portugal: Labour Markets, Smuggling and Gender Segmentation. International Migration 47, no. 3: 185-2010. [ Links ]

32. Pinto, Teresa. 2007. Industrialização e domesticidade no século XIX: a edificação de um novo modelo social de género. In Género, diversidade e cidadania, ed. Fernanda Hen-riques, 155-168. Lisbon: Colibri. [ Links ]

33. Sager, Eric W. 2007. The Transformation of the Canadian Domestic Servant, 1871-1931. Social Science History 31, no. 4: 509-537. [ Links ]

34. Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2006. Globalizations. Theory, Culture & Society 23, no. 2-3: 393-399. [ Links ]

35. Sarti, Raffaella. 2005. Domestic Service and European Identity. In Proceedings of the Servant Project, Vol. V, eds. Suzy Pasleau and Isabelle Schopp, 195-284. Liège: Editions de l'Université de Liège. [ Links ]

36. Sassen, Saskia. 2007. A Sociology of Globalization. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [ Links ]

37. Supiot, Alain. 2006. Law and Labour. New Left Review 39: 109-122. [ Links ]

38. Supiot, Alain. 2010. A Legal Perspective on the Economic Crisis. International Labour Review 149, no. 2: 151-62. [ Links ]

39. Valenzuela, María Elena and Claudia Mora. 2009. Esfuerzos concertados para la revaloración del trabajo doméstico remunerado en América Latina. In Trabajo doméstico: un largo camino hacia el trabajo decente, eds. María Elena Valenzuela and Claudia Mora, 285304. Santiago: ILO. [ Links ]

40. Wall, Karin, and Cátia Nunes. 2010. Immigration, Welfare and Care in Portugal: Mapping the New Plurality of Female Migration Trajectories. Social Policy and Society 9, no. 3: 397-408. [ Links ]

41. Walsum, Sarah van. 2011. Regulating Migrant Domestic Work in the Netherlands: Opportunities and Pitfalls. Canadian Journal ofWomen and the Law 23, no. 1: 141-165. [ Links ]

42. Weber, Max. 1978 [1911-13]. Economy and Law (the Sociology of Law). In Economy and Society, Vol. 2, Max Weber, 641900. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Fecha de recepción: 12 de junio de 2012 Fecha de aceptación: 13 de septiembre de 2012 Fecha de modificación: 9 de octubre de 2012