Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista de Estudios Sociales

versão impressa ISSN 0123-885X

rev.estud.soc. no.52 Bogotá abr./jun. 2015

https://doi.org/10.7440/res52.2015.03

"History Is a Verb: We Learn It Best When We Are Doing It!": French and English Canadian Prospective Teachers and History*

Stéphane Lévesque**, Paul Zanazanian***

** PhD in Educational Studies (University of British Columbia, Canada). Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Ottawa (Canada). His latest publications include: What is the Use of the Past for Future Teachers? A Snapshot of Francophone Student Teachers in Ontario and Québec Universities. In Becoming a History Teacher: Sustaining Practices in Historical Thinking and Knowing, eds. Ruth Sandwell and Amy von Heyking. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014, 115-138, and A Giant with Clay Feet": Québec Students and Their Historical Consciousness of the Nation (with Jocelyn Létourneau and Raphaël Gani). International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research 11, n° 2 (2013): 156‐172. E-mail: stephane.levesque@uOttawa.ca

*** PhD in Comparative Education and Educational Foundations (Université de Montréal, Canada). Assistant Professor in the Department of Integrated Studies in Education at McGill University, Canada. His latest publications include: History is a treasure chest: Theorizing a Historical Metaphor for Initiating Teachers to History and Assisting them to Open up Possibilities of Change for English-Speaking youth in Quebec. Journal of Eastern Townships Studies 43 (2014): 27-46, and Historical Consciousness and Metaphor: Charting New Directions for Grasping Human Historical Sense-Making Patterns for Knowing and Acting in Time. Historical Encounters Journal 2, n° 1 (2015): 16-33. E-mail: paul.zanazanian@mcgill.ca

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7440/res52.2015.03

ABSTRACT

This article presents the results of a Canadian study of prospective history teachers conducted in 2012-2013. Using an online questionnaire to assess a broad range of questions pertaining to their knowledge of history, their trust in historical sources, their experiences in high school and university classes, and their views about school history, it offers new empirical evidence on how the growing generation of Canadian teachers are prepared for the teaching profession. Implications of this study for teacher education and practice teaching are also presented.

KEY WORDS

History, education, Canadian teachers, experiences.

"La historia es un verbo: ¡La aprendemos mejor haciéndola!": futuros profesores de historia franco y anglo-canadienses

RESUMEN

Este artículo presenta los resultados de un estudio canadiense sobre futuros profesores de historia realizado entre 2012 y 2013. El estudio ofrece nuevas evidencias empíricas sobre la manera en que la nueva generación de profesores canadienses se está preparando profesionalmente, utilizando un cuestionario en línea para evaluar una amplia gama de preguntas relacionadas con sus conocimientos de historia, su confianza en las fuentes históricas, sus experiencias en clases a nivel secundario y universitario, y sus opiniones sobre la historia que se enseña en los colegios. El artículo también presenta las implicaciones de este estudio para la formación de los profesores y su práctica docente.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Historia, educación, profesores canadienses, experiencias.

"A história é um verbo: aprendemos melhor fazendo!". Futuros professores de história franco e anglo-canadenses

RESUMO

Este artigo apresenta os resultados de um estudo canadense sobre futuros professores de história, realizado entre 2012 e 2013. O estudo oferece novas evidências empíricas sobre a maneira em que a nova geração de professores canadenses está sendo preparada profissionalmente, utilizando um questionário on-line para avaliar uma série de perguntas relacionadas com seus conhecimentos de história, sua confiança nas fontes históricas, suas experiências em sala de aula do ensino médio e universitário, e suas opiniões sobre a história que se ensina nos colégios. O artigo também apresenta as implicações desse estudo para a formação dos professores e sua prática docente.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

História, educação, professores canadenses, experiências.

The teaching and learning of Canadian history has been a subject of ongoing interest and controversy, notably due to the nature of the country as a federal compact between French-speaking and English-speaking Canadians. Since the creation of the federation in 1867, issues of history and identity have divided Canadians along linguistic and cultural lines, as have the workings of their respective historical consciousness as members of two parallel national communities within a common territorial and civic state. Which history should be taught? What perspective should teachers take? What knowledge should be assessed? And in terms of teacher preparation, which epistemological understandings of reality and history ones that influence both national and professional identity should teacher educators take into account for preparing prospective teachers to take ownership of their practice? On the eve of Canada's centennial celebrations in 1967, the National History Project led by Professor A.B. Hodgetts addressed these questions through the first-ever national assessment of history and civics teaching and learning. Over the course of this comprehensive investigation, Hodgetts and his team surveyed 10,000 students across the country, observed 847 classroom teachers in 247 schools, and interviewed over 500 of them. The report came to a bleak conclusion on the state of history education in Canada (Hodgetts 1968). First of all, English- and French-speaking Canadians were being taught two fundamentally different histories, holding the potential for what Hodgetts conceivably feared as a gateway leading to the country's eventual demise. Secondly, beginning history teachers lacked sufficient knowledge of the subject matter to teach it in an engaging and critical manner, one that would make up for the differences in perspectives between Canada's two main language communities. All in, it seemed that the historical consciousness of prospective teachers, or what we might conceive of as their capacity to give meaning to the past in order to make sense of and act in present-day reality (Rüsen 2005; Zanazanian 2012 and 2015), played a central role in developing their identity as teachers. Furthermore, although such an impact was not viewed negatively in and of itself by Hodgetts (1968), it had to be geared towards developing a stronger commitment to fostering a sense of a united Canadian identity and polity among students.

Hodgetts also criticized teacher-training institutions for not providing adequate awareness of and sensibility to Canadian history, the result being that "teachers leave university to enter the profession with the same feelings and attitudes toward Canada as those held by Grade 12 students in high school" (1968, 102). Finally, Hodgetts blamed academic programs for much of the teachers' own conservative approach to history. Canadian history, as taught to future teachers, the report claimed, "is much too purely factual, it is seldom used to develop historical concepts or ideas, and it is equally enslaved by the textbook" (1968, 99). In other words, teachers were graduating from universities with the same weaknesses in knowledge and teaching approaches as those their students were revealing "in more intensified forms" when they left high school.

More recently, similar criticism about the state of Canadian history education has been voiced publicly (Granatstein 1998; Osborne 2003; Sandwell 2012). Throughout North America, teacher education has been decried and put at the forefront of efforts at improving education in schools. "It has been more or less assumed," Marilyn Cochran-Smith and Susan Lytle observe, "that teachers who know more teach better" (Barton and Levstik 2004, 245). But this statement begs the question: What does it mean to know more for a history teacher? Traditionally, the idea of knowing more history was equated with the accumulation of historical knowledge that teachers were supposed to possess and transmit to their students. Assessment was, therefore, conceptualized as a straightforward process of measuring the acquisition of this knowledge. It was, however, precisely in light of such similar practices in the United States in the 1960s that Lee Shulman was led to call for fostering his notion of "pedagogical content knowledge" among future teachers (Shulman 1986 and 1987; Shulman and Quinlan 1996). Shulman argued that pedagogical content knowledge is of special interest "because it identifies the distinctive bodies of knowledge for teaching the category most likely to distinguish the understanding of the content specialist from that of the pedagogue" (1987, 8). For him, competent teachers were those who had a thorough teaching knowledge base, which he represented graphically as the intersection between content and pedagogy.

The works of Shulman have had a wide educational impact in many areas, including the field of history education. Indeed, growing research suggests that knowing history is more complex than mastering vast historical facts, just as bridging the gap between novice and expert is harder than overcoming the disparity between disciplinary knowledge and pedagogy among future teachers (Fallace and Neem 2005; Fallace 2007 and 2009). As Hodgetts found in his study, exemplary history teachers possess and deploy strategic forms of knowledge, which implies "doing history;" engaging learners in historical activities and inquiries, sourcing historical information, assessing the value of sources, and considering various perspectives. These strategic forms of knowledge can be understood today as being informed by the workings of teachers' historical consciousness and their own views on pedagogical content knowledge (Hartzler-Miller 2001).

As we approach the celebration of Canada's 150th anniversary, Canadians wonder whether things have really changed in history education over the past few decades. Are teachers better prepared than they were in the 1960s? What experiences do they get in their academic programs? Do French-speaking and English-speaking Canadian teachers have the same vision regarding history? These questions need urgent answers, especially for assessing the quality of knowledge and competencies being transmitted to students who are destined for productive lives as well-functioning citizens both in Canada and in a globalized world. Unfortunately, ever since the National History Project of 1968, Canadian educators have had only a limited understanding of how teachers, and beginning teachers in particular, think about history. Although we may find some action-research on classroom assessment projects in the literature (Lévesque 2003 and 2009; Charland 2003; Peck and Seixas 2008; Cardin, Ethier and Meunier 2010), we lack a more global assessment of Canadian history teachers' backgrounds, their engagement with history, and their experiences in the history classroom.

In its own way, the present article aims to fill this void by evaluating these issues through a survey study conducted on beginning teachers in teacher-education programs in Canada. The goal was to offer scholars and teacher educators possible assessment instruments and related research findings on how beginning teachers use and think about history in their personal and professional lives. In doing so, the study espouses an historical consciousness mindset for interpreting these findings, and for specifically looking at how prospective teachers' means of knowing and acting in time through their understandings of history impact their pedagogical content knowledge as well as their engagement with and feelings of national attachment to Canada. In providing guidance, historical consciousness specifically constitutes "an ability to mobilize significations of the past both the narrative configurations of the past and the interpretive filters used to make sense of temporal change for effectuating the necessary moral decisions to orient oneself in given social relationships" (Zanazanian 2015).

As a result of this objective and an understanding of historical consciousness, the study attempts to comment on the relevance of such survey instruments as assessment tools for helping to further understand the field of history teaching and the needs of prospective teachers. In using our survey as an assessment tool to measure the quality of teacher preparation in the area of history education, we try to measure the extent to which Canadian history teachers are being better prepared to teach an inquiry-based, disciplinary approach to national history, and the extent to which the perspectives of both official language groups are being transmitted to English-and French-speaking students throughout the country.

Our educational project was supported by the research unit "Making history/Faire l'histoire" of the University of Ottawa and was modest in its goals and resources. Inspired by the nationwide research project Canadians and Their Pasts (Conrad et al. 2013), which surveyed nearly 3500 adult Canadians across the country using a telephone questionnaire, our online survey was first piloted with prospective teachers in three university classrooms in 2010-2011 (Lévesque 2014). The final version of the bilingual instrument was put online in 2012 using Surveymonkey (www.surveymonkey.com/s/historiprof). In order to contribute to the study, prospective teachers had to complete a consent form, select the language of participation, and complete a series of 53 questions dealing with their relationship to history (including multiple-choice and open-ended questions). A number of different strategies were adopted to maximize the number of participants.

We first contacted professors of history and social studies education across the country by email in September 2012 and informed them about the study. We asked that they present the project (via a description sheet) to their history/social studies students, and invited them to go online and complete the questionnaire individually. We also posted a bilingual invitation on The History Education Network website (www.thenhier.ca), the largest organization dedicated to history education in Canada, which reaches out to thousands of web-visitors. A total of 341 participants accessed the online survey between September 2012 and May 2013. However, 108 of these participants did not complete the consent form or the full questionnaire, thus bringing the total down to 233 participants. Of this number, 178 (76%) completed the survey in English and 55 (24%) did so in French.1 Women accounted for 74% of the participants compared to 26% for men. Overall, 88% of participants were born between 1980 and 1990. The geographical distribution of participants was as follows: Manitoba (1), Nova Scotia (1), British Columbia (2), Saskatchewan (6), New Brunswick (7), Alberta (13), Ontario (78) and Québec (125). We understand that the sample of voluntary participants is not characteristic of the entire Canadian teacher-education population due to a high degree of representation from the two most populated provinces (Ontario and Québec). Nevertheless, we believe it does represent a rich and substantial sample of the present-day cohort of beginning history and social studies teachers for these two central Canadian provinces. In this way, our assessment offers a unique portrait of the growing generation of teachers in our education programs; some might even say the future of the profession.

Academic Background and Knowledge of the Subject

There is a growing consensus in history-education research that professional teachers need to possess deep knowledge of their discipline (VanSledright 2011). Even Shulman confessed "the teacher has special responsibilities in relation to content knowledge, serving as the primary source of student understanding of subject matter" (1987, 9). Several critics in Canada have suggested that teacher education today pays too much attention to questions of pedagogy and classroom management at the expense of disciplinary expertise, the result being that the current generation of teachers are mere "learning instructors" trained to fit the labour demands of the school system (Coalition pour l'histoire 2012; Lavallée 2012). Already in the 1960s, Hodgetts was stunned by the fact that few Canadian history and social studies teachers had an academic background in their discipline. What does our study tell us about current prospective teachers?

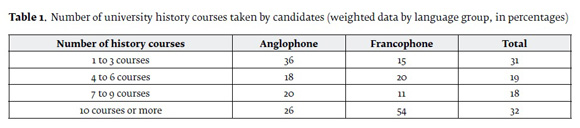

First, it is worth noting that all participants in our study were registered in a Canadian teacher-education program at the time of the survey. However, the length of these programs varied considerably across the country, from a one-year post-graduate degree in the province of Ontario to a four-year combined degree in Québec. As Table 1 indicates, 32% of our participants had completed at least ten post-secondary courses in history at the time of the survey. An almost equal number (31%) had taken from one to three courses in history, while 37% declared having taken between four and nine courses.2 These findings imply that the majority of current prospective history and social studies teachers (68%) will find themselves teaching in Canadian schools with fewer than 10 academic courses in history.

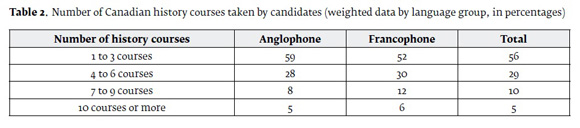

When looking more explicitly at the type of academic background of prospective teachers, we find that the number of participants who have taken a large number of courses in Canadian history is significantly lower than those who have not done so. As Table 2 indicates, only 5% had completed 10 or more courses in Canadian history. The majority (56%) of participants had taken between one and three courses, while 39% claimed to have taken only between four and nine courses. In arguing that the more Canadian history courses students take, the more their knowledge in the field increases, some may find these findings disturbing, for they suggest that only a small minority of prospective teachers could claim to have extensive academic knowledge of Canadian history. The results are, moreover, consistent with what Hodgetts found when he revealed that 52% of Canadian teachers had taken only one such course (Hodgetts 1968), thereby implying that not much has changed since the 1960s. But another perspective can also be taken on these findings. In comparing Tables 1 and 2, it becomes clear that among those students who took more than seven courses in history (50%), about one third of them took six or fewer courses on Canadian history, with most of them taking from one to three courses, as can be seen in the significant increase in that category. This would mean that for many prospective teachers who have taken a significant number of history courses, Canadian history accounts for at least half the number of history courses they did take, which in and of itself is interesting, given their overall course load and expectations for graduating.

An important question thus arises. How many courses in Canadian history do history teachers actually need in order to be considered or to feel adequately prepared to teach the subject to their students? While 5% taking ten or more courses may be too low, some may consider that 44% with more than three preparatory courses in Canadian history sufficient, as long as teachers are trained and motivated to do further research to obtain information on their own, both for improving their own knowledge base and for offering their best to their students.

That being said, it is important to note that there is a major variation between the two language groups with regard to academic background. Francophone participants are more likely to have taken history courses than their English-speaking counterparts, which can be explained in a number of ways. First, prospective teachers registered in teacher-education programs in the provinces of Ontario and Québec must complete a given set of courses in their subject-areas (known as "teachables"), including history. However, this is not necessarily the case in other provinces for registered prospective teachers taking "social studies" education, which includes several social science disciplines (history, geography, political science, law, etc.). Second, a greater number of participants in the Anglophone group are registered for teaching at the junior and intermediate levels (elementary/middle school). Even in the provinces of Ontario and Québec, the number of credits required to teach history at these school levels is lower than the number of credits required for high school. Finally, the number of participants with graduate degrees (Master's or PhD) is significantly higher in the Francophone sample (23%) compared to the Anglophone one (7%).

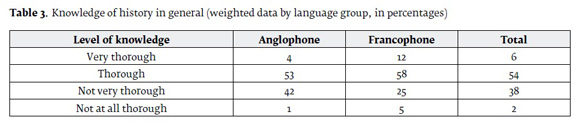

In order to consider the possible effect of these academic background results on prospective teachers, we asked participants to evaluate their own self-reported knowledge of history. As Table 3 indicates, few (6%) claimed to have a "very thorough" knowledge of history, even among the Francophone group, which presents twice as many prospective teachers with a history-major background. A majority of participants (54%) believed themselves to have a "thorough" knowledge of history in general, while 38% indicated having a "not very thorough" knowledge of history. This number is even greater among participants from the Anglophone group (42%), which was also reported earlier (see Table 1) as having fewer university courses in the discipline. In comparing the groups, the relationship between declared knowledge and number of courses taken (Table 1) seems to have a higher correlation for Francophones, as can be seen in their self-declared good grasp of history (70%, grouping "very thorough" and "thorough" together) and the number of courses seven or more that they have taken in general history (65%). Interestingly, the same cannot be said for the Anglophones, whose good grasp of history (57% grouping "very thorough" and "thorough" together) correlates weakly with the same number between seven and ten of general history courses taken (46%). What accounts for this difference? Could the English-speaking prospective teachers who believe they have acquired a good grasp of history be thinking that they have done so through activities outside of their teacher-preparation courses? Where does such self-confidence in their knowledge of history come from?

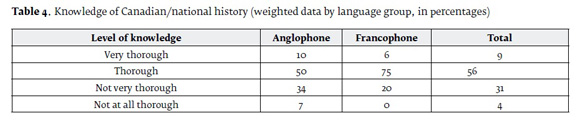

Data on prospective teachers' assessment of their own knowledge of Canadian history offers comparable results (Table 4), with only 9% of participants declaring themselves to have a "very thorough" knowledge of Canadian history, while most participants claimed to a have a "thorough" (56%) or "not very thorough" (31%) knowledge of national history. As in the previous table, Anglophone participants claimed to have only a weak grasp of Canadian history (41%), grouping "not very thorough" and "not at all thorough" together, compared to 43% regarding knowledge of history in general. Curiously, however, a slightly higher proportion of participants (10%) claimed to possess a "very thorough knowledge" of Canadian history than of general history, bringing the total of Anglophones claiming to have a good grasp of Canada's past to 60% ("thorough" and "very thorough" together). This is relatively lower than the proportion of their Francophone counterparts (81%) who believe they have a good grasp of Canadian history ("very thorough" and "thorough" knowledge). Although it is not clear what the respondents were actually thinking when they gave their answers, nor what the quality of the courses they took was like, questions nonetheless arise regarding this difference. What could account for Francophones thinking they have a good grasp of history, more so than their Anglophone peers do? Could it be related to how both groups are taught history? In following Hodgetts' logic of the transmission of two different national histories, could it be related to the workings of the participants' historical consciousness in responding to the survey questions? If so, could it be that the Francophones' notion of group survival, reflecting a more pronounced collective memory and group identity, instinctively makes them think that they know history, even if they do not necessarily know its historiographical workings? In comparison, could English-speaking Canadians still be offered a "bland" historical storyline in schools, as Hodgetts has claimed, hence mirroring a disinterest in Canadian history that could account for their declaring a weaker knowledge of it?

Overall, there is a clear correlation between the number of university courses taken and the level of knowledge of history that participants claim to have. The majority of those who indicated a "not very thorough" knowledge of history (60%) had taken between one and three history courses (in general and Canadian history). These findings are comparable to one of Hodgetts' most important conclusions: prospective teachers' generally weak knowledge of the subject, and hence of the academic background knowledge they professed in this regard. In bringing the total for Anglophones and Francophones who had taken from one to three courses on Canadian history to 56% in Table 2, these findings correlate with the 52% in Hodgetts' sample who had taken only one Canadian history course. One could thus assume they were insufficiently prepared for teaching history to students. There nonetheless remains a significant gap between the 56% who had taken from one to three courses and the 35% who declared a weak grasp ("not very thorough" and "not at all thorough") of Canadian history, suggesting that even if they were to take from only one to three courses in Canadian history, some of them might still believe they possessed enough knowledge to teach it.

Similarly, in comparing the 5% in Table 2 who had taken ten or more courses in Canadian history with the 4% that Hodgetts describes as prospective teachers with specialized training in Canadian history, our survey also suggests a comparable finding. However, in looking at the 65% who claimed to have a good grasp ("very thorough" and "thorough") of Canadian history in Table 4, there seems to be a discrepancy when measured against the number of courses taken. Even if you were to add the 10% who had taken from seven to nine courses, and the 29% with four to six courses, to the 5% in the ten or more courses category, it brings the total of those with more than four courses to 44%, thus suggesting that even if participants in our sample were to take several courses in Canadian history, they would still believe to have a significantly higher grasp of the subject matter. That is to say then, that taking a high number of Canadian history courses does not necessarily correlate with teachers' self-confidence in having a good grasp of Canadian history. This raises some questions. Does the number of courses really matter? Should the number of courses and the declaration of a high level of knowledge correlate? Could we make the same case Hodgetts did, i.e. that "most teachers do not receive or take enough post-secondary-school academic courses to become proficient in Canadian studies" and thus "cannot be expected to do a good job" (Hodgetts 1968, 98-99)?

If pushed further, these findings lead to the notion of motivation and self-engagement. If the number of courses in Canadian history does not necessarily matter with regard to self-confidence in the subject area, how can we know that teachers will be motivated to acquire the historical knowledge that they lack once they are working in the field? Would interest in history be an indicator, based on the assumption that if there is a genuine interest in and passion for history, that prospective teachers will be prompted to seek out more information on their own? Fenstermacher (1986) is of the view that teacher-education ought to be conceived in a way that aims not to train teachers but to educate them to reason soundly about their practice and growth in their expertise. In other words, beginning teachers should be taught how to use their knowledge base and seek out information they need to make sound pedagogical decisions.

The results of our survey show great interest in history among prospective teachers. As Table 5 indicates, 58% of participants indicated being "very interested" in history in general, 50% in world history, 39% in family history, and 36% in Canadian history. As can be seen, the 36% who professed interest in Canadian history is relatively low compared to the first three categories, but when subsuming the categories "Family," "Provincial," and "Local" history under it, the percentage of "very interested" participants increases, suggesting potential for motivation. If the factors that transform great genuine interest in various aspects of Canadian history into motivation are met, would a high concentration of university-level courses taken in the subject area still be an indicator of teachers' self-confidence and ability to teach? We could argue that if approaches were provided to help prospective teachers connect various aspects of Canadian history (family, provincial, and local), perhaps they would be more willing to offer better historical teaching to their students and thus spark greater curiosity and interest in the subject matter.

When looking at the response breakdown according to language group, another revealing trend seems to emerge, again reflecting the way prospective teachers may have been taught history when they were in high school. As Table 5 indicates, a significantly greater number of Francophones (50%) declared they were "very interested" in Canadian history, more so than Anglophones (31%). When adding the percentages of Francophones interested in Canadian, Local, and Provincial histories, the total amounts to over 100%, while the total for the same categories for Anglophones comes to only 70%. This is an enormous difference, especially since a greater proportion of Anglophones than Francophones participated in the study. Such a major difference in terms of interest would suggest that Francophones are comparatively much more interested in histories related to notions of space, positionality, or territory that mirror, either from near or afar, their sense of national, provincial, or local self. Does this again relate to a possibly (un)conscious affinity for their own cultural heritage, as an implicit effect of their different processes of group socialization within Canada? This line of thought stands out more when contrasted with their Anglophone counterparts. Indeed, if Anglophones can be seen as forming part of the more dominant community in Canada, whose culture and language possess greater social capital than that of Francophones, it could possibly explain why more Anglophones have a greater interest in World and Family history combined (92%) than they do for Canadian, Provincial, and Local history combined (80%), which is a point difference of 12%. It may well be that when an individual is part of a dominant majority group, they can simply afford the luxury of extending their focus to other areas of historical interest, knowing that their sense of historical identity is perceived as already being secure.

Trust in Historical Sources

Prospective teachers, despite their diverse educational backgrounds, are clearly interested in history, but what sources do they trust to tell them what happened? What value do they place on the stories of the past that they encounter in museums or in movies? To what degree do they consider teachers to be trustworthy sources of information about the past? These questions are extremely important because they help to understand how prospective teachers sort out the problem of historical veracity in a 21st century culture dominated by multiple versions of conflicting historical information.

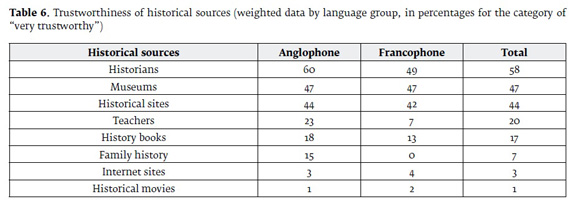

As Table 6 indicates, 58% of prospective teachers judged historians to be "very trustworthy" sources of information, followed closely by museums (47%), and historical sites (44%). Participants justified their decision by making reference to the notion of "experts in the field," as many put it in their justifications. Surprisingly, teachers are considered a "very trustworthy" source by only 20% of participants. For many, the trustworthiness of teachers varies considerably because, as one Francophone participant observed, "not all teachers have the same educational background." This is a revealing statement because many prospective teachers know first-hand that, unlike professional historians, history teachers in Canada often have very diverse educational experiences and university backgrounds, which may affect their credibility as a trusted source of historical information.

Equally interesting are the results dealing with the Internet and historical movies. While prospective teachers use them extensively in their daily life, only 3% of participants found Internet websites to be "very trustworthy." As one participant stated, "I think they have the possibility of being very trustworthy but tourism and traffic is a cash cow and I can't help but think that certain sites will try to play up their significance." Historical movies, which came in last (1%), suffer from similar shortcomings. Their historical value as anything beyond mere entertainment was repeatedly questioned. According to one participant, "Hollywood movies are notoriously unreliable." Others, however, were more specific in their assessments and made important distinctions between documentaries and historically-based movies, noting that "it depends on whether or not the movie is a documentary versus an 'interpretation'." In the face of such authority figures as families, our participants were also critical. One prospective teacher noted, "family stories are easily exaggerated [sic] or embellished over time, especially if there is no written record."

For most categories, we find relatively small variations between the two language groups except regarding the trustworthiness of teachers (23% for Anglophones versus 7% for Francophones) and family stories (15% for Anglophones versus 0% for Francophones). This lower figure for teacher- trustworthiness raises important questions regarding our participants' future sense of professional purpose once they are in the field. If they do not find teachers to be "very trustworthy" in great numbers, could this then translate into a desire to develop a better sense of professional rigour and responsibility that would make up for it? Moreover, could the discrepancy between Francophones and Anglophones in terms of their perception of teacher-trustworthiness also be related to the heightened identity politics among French-speaking Canadians, notably in Québec, where it is sometimes seen through a separatist versus federalist lens, or an "Us" versus "Them" outlook? Could it be reflective of divisions expressed around the family dinner table at home, which are then transposed into beliefs regarding teachers' trustworthiness, because they too would be presumed to harbour certain opinions or political biases? Obviously, more evidence is needed to answer these questions in any substantive way.

Views on School History

The prospective teachers in our Canadian survey represent a unique cohort of students. Not only did they all pursue post-secondary education in Canadian universities, but they were all also registered in a professional educational program to become teachers of history or social studies. So it is no surprise that nearly half of them indicated that history was their preferred subject in school. However, the challenge of being better at teaching history implies moving beyond personal interests in the past and acquiring both disciplinary and pedagogical content knowledge. To look more specifically at this aspect, our study included questions concerning classroom experiences, participants' perspectives on teaching approaches and resources, and their visions of school history. Such findings are extremely important because several studies (Barton and Levstik 2003; Cochran-Smith 2004; VanSledright 2011) suggest that many beginning teachers adopt teaching practices consistent with their familiar learning experiences and the school culture in which they teach. Hodgetts, writing in 1968, was appalled by the conventional environment that predominated in Canadian classrooms. He concluded that students were largely "bench-bound listener[s]," learning primarily from history lectures and textbook-based activities (Hodgetts 1968, 44). Four decades later, we can still ask what role prospective teachers envision themselves playing in the classroom.

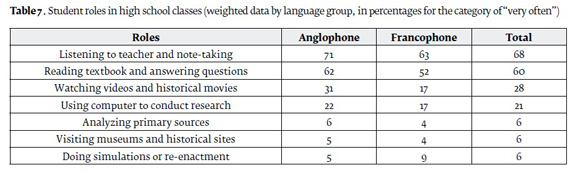

As Table 7 indicates, listening to teachers and note-taking continued to be the participants' dominant role in their own high school classes (68%), followed closely by textbook-reading and answering questions (60%). It was clear that activities such as the analysis of primary sources (6%), visits to museums and historical sites (6%), role-playing and re-enactments (6%) were not used very frequently by their teachers. As one Ontario student declared, "high school was very textbook-based learning I cannot really recall it being any more than such a classroom experience." Surprisingly, the use of computers for research (21%) was still marginal in Canadian schools in the late 1990s according to prospective teachers. According to this Ontario participant who was born in the 1980s, however, things may have changed, since "computers were not used anywhere near as often as they are today when I was in high school." When looking at the results for the two language groups, there is little variation particularly in the order of the categories presented in this table, thus suggesting that our participants generally seemed to have participated in the same activities as students in Canadian high schools, which still gave a preeminent place to traditional approaches to teaching history.

In light of these findings, we asked our student teachers to evaluate the same experiences in university. As Table 8 indicates, the primary function of students in their university courses was still to listen to their instructors and take notes (78%), followed by the use of computers to research historical information (51%), and reading from history textbooks (31%). Surprisingly, only a quarter of the participants reported analyzing primary source materials very often in university courses. An even smaller number said they visited museums or historical sites (6%), or did simulations or engaged in activities like re-enactments (2%). For one participant from Nova Scotia, there is a clear distinction between undergraduate and graduate educational experiences: "As an undergraduate student, my experience was limited to classroom lectures. However, as a graduate student, I was very active in class, and as a researcher I visited numerous archives, historical sites, and museums." Other participants corroborate this finding, making observations such as, "taking notes, listening and writing papers, a midterm exam that was my education as an undergraduate student in university." When comparing the two language groups, we find relatively similar roles for students in Canadian universities, except perhaps for note-taking and listening to instructors, which seem to be more frequent in the Anglophone group (82% versus 69%).

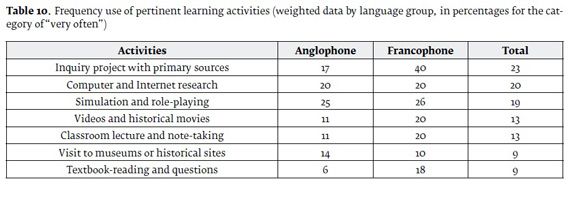

In the face of such findings, we asked prospective teachers to comment on the most pertinent approaches and learning activities they would prefer and use as practicing teachers. The results are very interesting for history education. As Table 9 shows, the preferred activity is the inquiry-based project using primary sources (32%), followed by computer and Internet-based research (26%), and simulations and role-playing (25%). The traditional lecture with note-taking ranked in fifth place (16%), just ahead of visits to museums and historical sites (15%) and textbook- reading (12%). These findings contrast with participants' experiences in university and high school. In many ways, prospective teachers seem to have embraced a greater variety of inquiry-based learning approaches, which emphasize "learning by doing," with authentic sources. For one Ontario respondent, "Engaging with history through primary source material is the most impactful way to help students understand it. Having fun with it makes the learning even more meaningful." Another participant commented on the potential role of technologies in students' learning: "The Internet is huge and an ever-expanding resource of information and media." Equally interesting are the comments regarding the need for emotionally powerful strategies of perspective-taking, such as this one from a Saskatchewan participant: "By using games and simulations, students feel a greater pull, empathy even, for those who went through the event that is being studied." These findings suggest that student teachers are keen on fostering critical and creative thinking as well as problem-solving skills among their students, perhaps something they would have appreciated more in high school and in university.

When looking at the data by language group, we find relatively similar results overall, except that Francophone participants are more likely to favour inquiry projects (39% versus 30%), lectures and note-taking (20% versus 15%), and textbook-reading (17% versus 10%) as "very pertinent." Conversely, Anglophone participants are also more likely to choose computer and Internet research (28% versus 22%) and visits to museums and historical sites (17% versus 10%) as "very pertinent" learning activities.

Barton and Levstik (2004) contend that what prospective teachers intend to do in class does not correlate with what they will actually do because, as they argue, teacher education has little impact on their practice teaching. As we did not have the opportunity to observe them in class, we asked our prospective teachers a follow-up question about how often they thought they would use the activities listed above, as well as their justifications for using them when in the field.

Of interest, the results in Table 10 are not drastically different from those in Table 9. Although the number of responses for the category of "very often" is significantly lower across all activities, the order of the categories remains unchanged. This highlights participants' recognition that some strategies may be more difficult to implement in school (e.g., inquiry projects), but not to the point of reversing their views about their importance for learning history. For one Toronto student, "this is not really an issue of desired teaching strategies, but rather one of resources. I would go to the [Royal Ontario Museum] with my class every day if only I could." For other participants, the need to prepare students in senior history courses for post-secondary education can also influence the type of activities used in class, as noted by one informant who said: "Although I do not value lectures a great deal, I do believe they should remain a part of the classroom to prepare students for university. The most important thing I wish to impart to the children though, is the value of a well-delivered argument which is useful in any future endeavour; research being a key to delivering a good argument." Perhaps the following statement from another Toronto student best summed up the views of many prospective teachers: "History is a verb we learn it best when we are doing it."3

Following the answers provided by participants on their preferred activities in class, we concluded the questionnaire by asking them to summarize, in one sentence, their rationale for teaching history in Canadian schools. The question was meant to look at their personal visions of school history as well as their justifications for the inclusion of history in the present educational system. By the 1960s, the National History Project had already discovered that (Anglophone) history teachers were becoming increasingly preoccupied with "the changing nature of society" and "the relativity of all knowledge" (Hodgetts 1968, 92). History was being understood more globally and contemporaneously, and less in Canadian terms. As one representative informant at the time put it, "The whole world is at our doorstep" (Hodgetts 1968, 93).

Because the question we asked prospective teachers was open-ended, we inductively generated broad categories from our analysis of their sentences. While most participants followed our instructions, some provided more than one rationale for history in schools. For these instances, we coded their answers according to our various categories. As Table 11 indicates, prospective teachers identified "understanding the present" (30%) as the most important rationale for teaching history in school, followed by an "orientation from the past to the future" (17%), education for citizenship (11%), learning "lessons from the past" (11%), critical and historical thinking (10%), and developing a "global/world understanding" (10%). Acquiring "knowledge about the past" (7%) and "identity-building" (4%) both came in last.

The first two categories combined (47%) suggest that prospective teachers ascribe an important role to history in providing an orientation mode for understanding present realities, and in preparing the future in reference to past realities. In this sense, school history seems to offer students a temporal framework for situating their own contemporary lives in the course of time. Many participants presented their rationale by offering statements such as: "To have students understand that people lived and made decisions, and that these decisions still effect our society," "To understand where they come from and how things are the way they are today," and "Learn about the world and what has formed it into the shape we are in today. You can't plan the future without knowing the past."

Interestingly, matters of citizenship, critical thinking and global perspective all received fairly equal mention in participants' statements, although there were some important variations between the two language groups. While the first category was clearly prevalent among all prospective teachers, Francophone participants were more likely to consider "citizenship education" (20% versus 7%), "critical and historical thinking" (14% versus 8%), and "identity-building" (10% versus 3%) as the main rationales for history in schools. The new History and Citizenship Education curriculum in Québec, implemented in 2006, has possibly been a key influence on the Francophone participants from that province. As one Québec participant put it:

Former de bons citoyens, intéresser les élèves à l'Histoire, développer l'esprit critique des élèves, le tout dans une démarche d'interprétation du passé pour mieux mesurer la complexité de leur environnement immédiat.

[Preparing good citizens, getting students interested in History, developing their critical thinking through an interpretative approach to the past so they better evaluate the complexity of their environment.]

Possibly lurking behind the influence of the History and Citizenship Education program is again an unconscious or inadvertent Francophone concern for identity and national survival as handed down through various processes of group socialization. When compared to Anglophones, Francophone responses regarding citizenship-education and identity-building seem to resemble the high level of identity politics that exists, particularly in the province of Québec, as seen in the following excerpts:

Créer une identité nationale chez l'élève et une meilleure compréhension du présent [Creating a national identity among students and a better understanding of the present]

L'objectif serait d'établir une connaissance nationale de l'histoire en étudiant les différentes interprétations. De permettre à chaque étudiant de faire un lien avec lui-même et le pays.

[The objective would be to establish a national knowledge of history through the study of different interpretations. To allow each student to make links between himself and the country.]

Développer un sentiment identitaire fort et développer le sens de l'analyse.

[Developing a strong feeling of national identity and analytical skills]

Conversely, Anglophone participants were more likely to talk about the importance of history for preparing for the future (19% versus 14%), in providing people with important history lessons (11% versus 0%) and in developing a global perspective (12% versus 4%). As some prospective teachers put it: "To give them a better understanding of the world, to introduce them to different ways of life and how the world has changed," "The main objective for teaching kids is for knowledge purposes and expanding their educational horizon," "If we cannot understand our past, we will make the same mistakes in the future. History is a verb." When compared to Francophones, this difference stands out, but when looked at amongst themselves, the rationale of teaching history for purposes of identity construction is very low, possibly reflecting a continued bland, consensual history in schools, as Hodgetts has pointed out.

Overall, when looked at comparatively, issues of identity and "nationality" (i.e., citizenship and nation-building) are more important to Francophones, while a global outlook and lessons from the past are more significant for Anglophones. Despite these differences, the two groups possess some similarities. Regarding the top two categories in Table 11, when each group is looked at separately, they seem to be comparable in this regard, meaning that there is some common view underlying the "Why teach history?" question: understanding the present and orientation from past to present. Hodgetts had argued that these two rationales were lacking in history-teaching across Canada, and that they should both be implemented. Referring mainly to English-speaking Canada, Hodgetts felt that such a lack was the root cause for why "Canadian history [was] almost useless as a stimulating school subject" (Hodgetts 1968, 21), reflecting a leftover from 19th century attitudes in which the need to study history was believed to be for its own sake, i.e., for its inherent interest and cultural values. Interestingly enough, the current Québec history program has been developed following the logic of these two rationales, which its detractors are arguing against and accusing of holding history hostage to the presentist needs of citizenship (Beauchemin and Fahmy-Eid 2014).

Another interesting and very revealing point, which would have dismayed Hodgetts, is the glaring indifference among both language groups for the other's history. Getting to know the other Canadian community better did not emerge as an underlying rationale for our participants. This is surprising, especially given Canadians' general understanding that both language groups do seem to co-exist in "two solitudes." Questions definitely arise, particularly as to why this is the case in our survey. What does it say about the level of French-English relations in the country, or about the level of importance accorded to it by Canadian history teachers? This lack reflects what Hodgetts stated in his report: "Canadian studies in schools of both linguistic communities do so little to encourage a mutual understanding of their separate attitudes, aspirations, and interests" (Hodgetts 1968, 34). In following this logic, do prospective teachers in our survey share a sense of a common Canadian heritage? Does this really matter today and, if so, why?

General Discussion

Hodgetts' assessment of both the teaching of Canadian history and the preparation of educators was rather dismal, pointing to what he considered an overarching lack of a proper sense of attachment to Canada among Canadian students from coast to coast. At least two main deficiencies underscored this concern: the teaching of two unconnected national histories among French- and English-speaking Canadians; and a poor level of knowledge of the subject matter among teachers responsible for teaching history (content knowledge, historiographical perspectives, and disciplinary/interpretive workings of history). In spite of challenges to Canada's national unity by two referendums on Québec sovereignty (1980 and 1995) and the increasing commitment to inquiry-based competencies in the teaching of secondary school history throughout the country in the last few decades, the same questions Hodgetts raised are still worth asking. Are today's teachers in Canada better qualified than teachers were before? Do they have a better understanding of Canadian history or of how to teach it more effectively for the purpose of developing a sense of Canadian citizenship and unity? Do they have a better understanding of the other language group?

To offer some answers, we have employed a national survey as an assessment tool to measure the quality of teacher preparation in the area of history education and determine the extent to which Canadian history teachers are being better prepared today to teach an inquiry-based, disciplinary approach to national history than they were in the 1960s. To demonstrate the relevance of our survey, we will focus on three main themes, and wrap up with a fourth. These are: the background knowledge of future history teachers; the extent of prospective teachers' exposure to and experiences with classroom lecturing and textbooks; prospective teachers' visions of history and beliefs, showing convergences as well as divergences between the two communities; and the importance of surveys, like ours, for assessing teacher's knowledge, experience, and vision regarding the teaching of national history.

Background Knowledge of Teachers

In order to better assess the background knowledge prospective teachers' and its relevance for their future careers, we asked ourselves the following questions. What do prospective history teachers seem to know or do in fact know as pertinent historical information acquired through their different educational trajectories? What are their overall interests and self-confidence levels in history in general and in Canadian history in particular? How do we think this knowledge and the emerging motivations will affect their classroom practices in the future?

The number of courses taken in Canadian history by participants in our survey seems to have more or less remained proportionately the same since Hodgetts' report. Questions nonetheless surface regarding the number of courses actually needed to be prepared for adequately teaching Canadian history. Do more courses in the discipline-area indicate better preparation for teaching the subject matter in schools? While we can always hope that students will take more courses, we can be sure that most of them will probably take fewer courses, possibly like those who have taken three or fewer courses in Canadian history in our survey. This choice is understandable given the structuring of teacher-education programs throughout the country and the many different types of credits they are required to obtain for their teaching certification. Should prospective history teachers still take more Canadian history courses? Or, as Fenstermacher (1986) suggests, should they be educated to learn how to self-direct and constantly learn history as part of their teaching responsibilities, and to research new relevant studies and findings as autonomous professionals working as historians in their communities? The work of Hartzler-Miller with American beginning-teachers provides some directions for action here. She suggests that helping history teachers to improve requires an understanding of "multiple notions of best practice" (Hartzler-Miller 2001, 691), but not every teacher is familiar with and supportive of the same approach to Canadian history. It is very possible that the growing generation of teachers might be more inclined to favour "best practices" that are in line with their own practical life and sense of purpose. In this sense, perhaps more effective strategies on how to use digital history sources like the Internet critically may be helpful and can complement the courses and teaching methodologies they learn in their history and didactic programs in a positive way. History educationalists may also be able to work more closely with teachers to create the necessary digital history resources in this regard.

The more courses teachers take may be seen as correlating with their levels of self-confidence, but, as our survey shows, this is not always the case. Some teachers claim to have knowledge of history without it necessarily correlating positively with the number of general or Canadian history courses they have taken. Further research is needed in this regard to understand precisely what extracurricular history-related activities these teachers are involved in that give them the necessary self-confidence for teaching. Once this is established, such "real-life" meaningful activities performed outside the formal school-setting may possibly be incorporated into the methods courses offered in teacher-education programs, including work with museum exhibits and oral history projects, or possibly even more narrative-based methodologies. These new activities could be tailored to various types of learners and can help develop a better-grounded sense of self-confidence among students, as well as a deeper sense of purpose in them as educators.

Empirical studies will also be needed to research the operations of teachers' historical consciousness and how this affects their professional investment in teaching-preparation time. Comparative studies can also help to discern existing inclinations to improve understanding of different perspectives on Canadian history, notably those of the country's official-language communities in all their diversity, and of First Nations, Inuits and Métis in various provincial regions. Variations in content also definitely exist, but given the tools and the sense of responsibility for getting such information on their own, some of the gaps outlined above can be closed. A good lead as an entry point for fostering curiosity about Canadian history would be to gear the teaching of content courses to the various types of interests expressed by learners. If educators were to take the pulse of their classrooms, they could more aptly connect their courses to their students' interests, which, as our survey suggests, include World, Family, Canadian, Local, Provincial, and American history. Using examples from these disciplinary areas and bringing them in with relevant teaching methodologies (historical thinking dimensions, narrative approaches to teaching history, oral history projects, museum-related work) could spark teachers' overall possession of knowledge and self-confidence. If given in concert with a heightened awareness of their own social posture, and if they were to make the underlying connections between their sense of purpose and the reasons why they would choose certain methodologies and approaches over others, teachers may also develop that important sense of responsibility so greatly needed to get more information on their own, and therefore not always need more courses in Canadian history (Voss and Carretero 1994; Wineburg 2001; Van Hover and Yeager 2007; Kitson 2007; Cercadillo 2010).

Exposure to History and Experience in School

In terms of prospective teachers' exposure to and experiences in schooling, our survey points to their heightened awareness of where they stand as educators. They are significantly aware of the need for an inquiry-based approach to teaching history, as well as for transmitting critical and creative thinking skills, but no clear information on what Canadian history means, and why and how they should transmit it seems to emerge. Their sense of purpose as future teachers of Canadian history should probably be improved through teacher-education programs. Our survey shows that the majority of prospective teachers are still confronted with conventional teaching methods, activities and sources of information. Without discounting the relevance of some of these approaches, e.g., classroom lectures, it is evident that history and teacher-education programs should make greater efforts to offer teachers more tools and first-hand experiences in using historical sources of information in this digital age.

Prospective teachers would like to introduce more inquiry-based historical projects into their teachings, well aware that they are not being engaged extensively in their own classrooms. The question remains as to whether they will maintain their self-acknowledged interest in doing so once they begin to work in the field. History-didactics professors should model through their own teaching the kind of work that prospective history teachers are expected to offer in their classrooms. This drive should nonetheless correlate with the teaching rationales of participants from both groups who are interested in "historical consciousness" operations in the classroom (understanding the past; orientation from past to future). Moreover, these rationales correspond to Hodgetts' call for Canadian Studies preparation programs in his report.

The survey examines teachers' faith in reliable sources of information for educational and pedagogical purposes. Based on these results, professors can bring in professional historians, for example, to talk about their work and the types of dilemmas they face in establishing the trustworthiness and reliability of the primary sources they use. They can also discuss how they develop their own perspectives on the past, dealing with their own subjectivities, and how they account for and handle different historiographical traditions. Such an approach has already proved to be useful as can be seen in Fallace's (2007, 2009) notion of immersing prospective teachers in a historiography course, which helped them break down compartmentalized thinking between the disciplines of history and pedagogy (see also von Heyking 2014). Similar input can also be gained by bringing in other guest speakers from museums and historical sites to talk about the kind of work they do, and what their pedagogical objectives and dilemmas involve. On-site visits can also be advantageous for teachers. They may need to see how history is conducted in contexts other than formal educational institutions in order to grasp both the relevance of history for society and for the proper development of their students' own lives. The critical reading of Internet resources and historical movies may also constitute classroom activities, given their growing importance in public culture (Wineburg et al. 2007).

While the prospective teachers in our study do not seem to view family history as a reliable source of historical information, they could become acquainted with nationwide research projects like Canadians and Their Pasts, which point to how a majority of average Canadians engage with history through their families' past experiences. For example, Canadians and Their Pasts (Conrad et al. 2013) reveals that history matters to Canadians but, like any subject of intellectual inquiry, it can easily fall prey to abuses of all sorts for contemporary and ideological purposes. Therefore, reflecting on how different groups of people use and do history can help us to reflect on their historical consciousness and the role history plays in their lives so as to foster more critical and reflexive uses of the past.

In the face of such authority figures, our teacher participants were quite critical. As one informant noted, "family stories are easily exaggerated [sic] or embellished over time, especially if there is no written record." An entry point that serves as an example of family narratives of migration could encourage prospective teachers to grasp the larger national and international historical events upon which their personal histories unfold. Contact with such studies, conducted both in Canada and elsewhere, could better help them understand the relevance of history for society, and also help prospective teachers to decide on the pedagogical activities they would like to bring to their own teaching.

Vision of History and Beliefs

In contrasting the findings relevant to both language communities, our survey points to how the prospective teachers' historical consciousness greatly influences their sense of self-confidence regarding their declared levels of knowledge of Canadian history, their general interests in history, and their rationales for teaching the subject-matter in their classrooms. Underlying these influences are possibly the two separate ways in which English- and French-speaking Canadians are being taught their national history which, despite their polarizing tendencies in Hodgetts' day, tend to continue to do so in our current times.

Regarding Francophone Canadians, extensive research has demonstrated that their historical consciousness plays a central role in their ethno-cultural and national identification processes, where templates of survival or la survivance (Lévesque, Létourneau, Gani 2013) and national fulfillment weigh heavily in their cultural toolkits (Létourneau and Moisan 2004; Zanazanian 2012; Zanazanian and Moisan 2012; Létourneau 2014). Research has also demonstrated that shared historical memories of often unequal intergroup power relations with the Anglophone "Other" greatly influence the way many students and teachers make sense of the past for knowing and acting in time (Zanazanian and Moisan 2012). In accordance with Hodgetts' claim that Francophones were being taught a national history pivoting on such core notions as national identity and survival, there are some ways in which our survey points to how the effects of such historical sense-making patterns may still impact prospective history teachers. In terms of their declared levels of knowledge of history, the Francophones' sense of possessing a better grasp of their past could definitely be linked to their deeply ingrained survival template, which continues to be one of the defining cornerstones of their community's history in Canada. A Québec-centric storyline permeates the current History and Citizenship Education program, despite its emphasis on developing historical thinking and other related competencies. It thus follows that having a propensity for a strong sense of ethno-cultural or national identity and collective memory may contribute to prospective teachers' own beliefs that they know history, even if they do not necessarily know its underlying thought processes and historiographical workings.

A similar logic comes into play regarding their general levels of interest in the past. The Francophones' greater interest in Canadian, provincial, and local history may possibly point to their being embedded in ongoing historical and political discourses that (un)consciously speak to the urgency of national self-fulfillment as a means of preserving their nation and or to having a better understanding of their ethno-cultural and national selves, lest they forget where they came from and where they are headed. The perception of their language community's inferior status in Canada in comparison to Anglophones may also influence Francophone teachers' level of interest in history, where a fascination with their own history may satisfy a need for a sense of group prestige and serve to remind them of the importance of and motivation for having a stronger collective memory and identity as a historic community. If Francophone prospective teachers do in fact have a greater interest in history that is related to their imagined community or to their sense of identity, it thus mirrors a legacy and inherited mindset or attitude that has been handed down to them from long before the days of Hodgetts' report, when they were taught a history of survival. In light of their history in Canada and their shared collective historical experiences, that frame of mind has been instilled over time, and today forms an integral part of Francophone historical consciousness as a language group, which can be seen as a trans-generational impact of the way history has been taught to French-speaking Canadians.

The same logic can also be seen as underlying prospective teachers' greater focus on citizenship- education and identity-building as rationales for the teaching of history. Québec's high level of identity politics points to this, as it also mirrors French-speakers' sense of minority status in the country and in North America in general. To this day, such an historical consciousness still holds the potential for nourishing nationalistic views among teachers, as evidenced by the recent support among some teachers and professional associations for the proposed reform of Québec's history programs.

An historical-consciousness mindset can also possibly account for the professed weaker knowledge of Canadian history among Anglophones, their greater interest in world and family history, and their rather low score for identity construction as a history-teaching rationale. If English-speaking Canadians are still provided with a bland, consensus storyline based on narrow political and constitutional events, as Hodgetts has claimed, or as what Daniel Francis (1997) has more recently described in his book National Dreams, Myth, Memory, and Canadian History as a larger myth of Canadian unity in diversity, these results would make sense, especially in terms of claims regarding knowledge a dry, political, constitutional narrative that does not incite much excitement and fosters only an apathetic connection to the past.

Similarly, because they seem to possess a collective memory that is less populated by foundational myths and heroes than their French-speaking compatriots, the Anglophones' greater interest in world and family history, as well as their different history-teaching rationales, may reflect the luxury that comes with their language community's higher status in Canadian society, and their predominant linguistic status in Canada and North America in general. They thus have the luxury that members of dominant groups usually enjoy, i.e., that of being able to take certain cultural artefacts and representations for granted. English-speakers' norms and values as well as their self-image as a civic nation already permeate all of Canadian society through national symbols, with English being the strongest language in terms of communication.4

Do these different functions of historical consciousness constitute a challenge to fostering a sense of Canadian unity among students? Even if they are not always clearly pronounced, such patterns for knowing and acting usually do seep into the general mindset of individuals. Is this something that needs to be addressed if we want to foster student-teachers' interest in getting to know more about the other language community? More research is urgently needed on this subject of national significance.

Importance of Using Such Tools As Survey Instruments to Assess Teachers' Knowledge, Experience, and Vision

The online-survey method for teaching and assessing teachers is rather unique and effective because it helps raise necessary questions that require further qualification. It can also be an educational tool. If brought to prospective teachers, it can enable them to reflect on these issues and try to find answers on their own and inspire them to develop a stronger social posture/sense of purpose. Furthermore, it can also enable them to develop surveys of their own as a means of getting more involved in the processes of thinking about their profession and what their responsibilities should involve at the local, national, and international level.

However, surveys like ours have both benefits and limits. While they allow for a more global "cartography" of prospective teachers' ideas across a vast and regionally divided country like Canada, they nonetheless also have a very low resolution scale, which makes it difficult to evaluate teachers' own practices accurately. Unlike the study conducted by Hodgetts, an online survey instrument like this one does not compare with the wealth of findings that would emerge from direct classroom observations. As Hodgetts has argued, this is where action takes place and, therefore, it should be the focal point of any study of history education. Unfortunately, such observations are very research focused and labour intensive and would require greater financial and institutional resources to be accomplished. As such, we believe that comprehensive surveys like ours should be used in conjunction with other research instruments that are meant to assess the historical thinking and practice of prospective teachers.

Conclusion

It is clear from our national survey that the historical consciousness of both French- and English-speaking prospective teachers in Canada affects the way they learn, teach, and engage with history, as well as their attitudes towards acquiring content-knowledge of the field and the necessary pedagogical tools. In addition, it is clear that prospective teachers from both language communities face similar professional and pedagogical challenges, the main difference being the degree of their historical consciousness and the different historical storylines that they have been taught about the past.

The participants in our survey already seem to possess the workings of a pedagogical vision when they enter the classroom. In addition, it seems that they would like to uphold or even to build on what they already have in mind. The only question is whether or not they will do so. It seems to us that the changes that have come about since the publication of Hodgetts' report may have more to do with curricular changes than with direct pedagogy, epistemology/methodology, and history as a discipline than anything else. Despite taking time to sink in, some important disciplinary ideas, such as the concept of inquiry-based learning, do catch on. The only issue at hand is whether such ideas are being taught adequately to teachers and whether prospective teachers actually understand what they are doing, and why.

Comments

* This study, inspired by the major research initiative Canadians and their Pasts (www.canadiansandtheirpasts.ca), was designed and supported by the Virtual History Lab and the Educational Research Unit "Making History/Faire l'histoire" of the University of Ottawa. We would like to thank all teacher candidates who voluntarily contributed to our survey.

1 Although the language selected by participants is not a precise indicator of their mother tongue, it is worth noting that 95% of participants completed the questionnaire in the language of their schooling. We can thus assume that participants who chose to complete the questionnaire in French belong to the French-speaking educational community broadly defined. The same can be said for the English-speaking participants.

2 Due to the types of questions in our survey, which sometimes allowed participants to choose more than one possible answer, and to the necessity of rounding off the percentages in the tables, it is possible that the totals do not always add up to 100%.

3 It is worth noting here that the concept of "history as verb" was first coined by Ruth Sandwell as part of her own research and practice teaching at the University of Toronto (Sandwell 2011). The concept seems to have gradually percolated into the history-education discourse and has been appropriated by student-teachers themselves to discuss their own views on history.

4 The only exception to this would be the English-speakers of Québec, who, despite their great diversity, are keen on strengthening their language group's vitality in a province where they only developed an acute awareness of their minority status with the introduction of Bill 101 in 1977, a law that limited access to English schools and made Francophones the main community for integrating social diversity and newcomers to the province.

References

1. Barton, Keith and Linda Levstik. 2003. Why Don't More History Teachers engage Students in Interpretation? Social Education 67, n° 6: 358-361. [ Links ]

2. Barton, Keith and Linda Levstik. 2004. Teaching History for the Common Good. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

3. Beauchemin, Jacques and Nadia Fahmy-Eid. 2014. Le sens de l'histoire - Pour une réforme du programme d'histoire et éducation à la citoyenneté de 3e et de 4e secondaire. Québec: Ministère de l'éducation, du Loisir et du Sport. [ Links ]

4. Cardin, Jean-François, Marc-André Ethier and Anick Meunier (eds.). 2010. Histoire, musées et éducation à la citoyenneté. Québec: éditions MultiMondes. [ Links ]

5. Cercadillo, Lis. 2010. Hazards in Spanish History Education. In Contemporary Public Debates Over History Education, eds. Eirene Nakou and Isabel Barca. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, 97-112. [ Links ]

6. Charland, Jean-Pierre. 2003. Les élèves, l'histoire et la citoyenneté: Enquête auprès d'élèves des régions de Montréal et Toronto. Québec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval. [ Links ]

7. Coalition pour l'histoire. 2012. Pour un meilleur enseignement de l'histoire du Québec dans notre réseau scolaire. Document of the Coalition pour l'histoire, <http://www.coalitionhistoire.org/contenu/pour_un_meilleur_enseignement_de_lhistoire_du_quebec_dans_notre_reseau_scolaire> [ Links ].

8. Cochran-Smith, Marilyn. 2004. The Problem of Teacher Education. Journal of Teacher Education 55, n° 4: 295-299. [ Links ]

9. Conrad, Margaret, Kadriye Ercikan, Gerald Friesen, Jocelyn Létourneau, Delphin Muise, David Northrup and Peter Seixas. 2013. Canadians and Their Pasts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

10. Fallace, Thomas D. 2007. Once More Unto the Breach: Trying to Get Pre-service Teachers to Link Historiographical Knowledge to Pedagogy. Theory and Research in Social Education 35 3: 427-446. [ Links ]

11. Fallace, Thomas D. 2009. Historiography and Teacher Education: Reflections on an Experimental Course. The History Teacher 42, n° 2: 205-222. [ Links ]

12. Fallace, Thomas D. and Johann N. Neem. 2005. Historiographical Thinking: Towards a New Approach. Theory and Research in Social Education 33, n° 3: 329-346. [ Links ]

13. Fenstermacher, Gary. 1986. Philosophy of Research on Teaching: Three Aspects. In Handbook of Research on Teaching, ed. Merlin Wittrock. New York: Macmillan, 37-49. [ Links ]