In 2008, Carlo Ginzburg published an essay in Italian titled Paura, reverenza, terrore. Rileggere Hobbes oggi. The same text, along with three more essays, was translated into French (2013) and Brazilian Portuguese (2014). An enlarged collection, including five essays, appeared soon after in Spanish in Mexico (Miedo, Reverencia, Terror. Cinco ensayos de iconografía política), a book which has not yet circulated in Colombia, although it has done so in countries like Argentina. Like the Spanish translation, the Italian version that appeared in 2015 (Paura, reverenza, terrore: cinque saggi di iconografia politica) includes, in addition to "Paura, Reverenza, Terrore," four more essays: "Mémoire et distance. Autour d'une coupe d'argent doré (Anvers, ca. 1530)," "David, Marat. Arte, política, religião;" "'Your Country Needs You.' A Case Study in Political Iconography," and "The Sword and the Lightbulb: A Reading of Guernica."

The essay on Hobbes, which has been widely disseminated in Europe, where it has led to discussions and heated debates, was published as a chapter by the journal Apuntes CECYP (2015) in Mexico, which made its wider distribution possible since it thus became available on the Internet.

Said essay is groundbreaking not only in its analysis and conclusions, the philological and semantic thoroughness of the method applied, and the way Ginzburg integrates biographical data from Hobbes' life, but also in the way he distances himself from other well-known interpreters of the author of Leviathan, such as Quentin Skinner. It is therefore very interesting to be able to engage in a conversation with Carlo Ginzburg on some of his favorite topics, which is why we have decided to pose some questions regarding that essay to the Italian historian on this occasion.

Renán Silva (RS): Professor Ginzburg, could you tell us something about your great interest in the world of images, political iconography in this case, and explain why you consider this kind of iconography so important for the work of historians?

Carlos Ginzburg (CG): My interest in visual evidence, as well as in the methods of art history, goes back to my youth. Fifty years ago (1966) I published an essay entitled "Da Warburg a Gombrich" ("From Warburg to Gombrich"), which has been translated into many languages, including Spanish. Later I published a book on Piero della Francesca, the 15th century Italian painter (Indagini su Piero 1981), which has been translated into Spanish as Pesquisa sobre Piero (1984). My interest in the intellectual tradition inspired by Aby Warburg and developed in the Library and Institute named after him (first in Hamburg, then in London) played an important role in the collection of essays we are talking about: Miedo, Reverencia, Terror. Cinco ensayos de iconografía política. As I argued in the introduction, Aby Warburg's notion of Pathosformeln (formulae of pathos) provided -as I realized retrospectively- a sort of fil rouge, a red thread that runs throughout all those essays.

Images are -nowadays more than ever- unavoidable. We are surrounded by and submerged in images: in the street, in movie theatres, on the screens of cell-phones, computers, TV sets. Those images act upon us (although we may also resist them). They shape our social environment, they mold our minds and emotions: we must learn to analyze them and their power.

RS: Professor Ginzburg, according to your analyses, in advancing beyond Thucydides by radicalizing and transforming one of that Greek historian's ideas, Hobbes posits fear as a structural element in the functioning of the State and as one of the keys to its formation as a modern institution. We would like to know your opinion of the role that "fear," even reverence, and its most extreme form -terror- plays in the functioning of the State today.

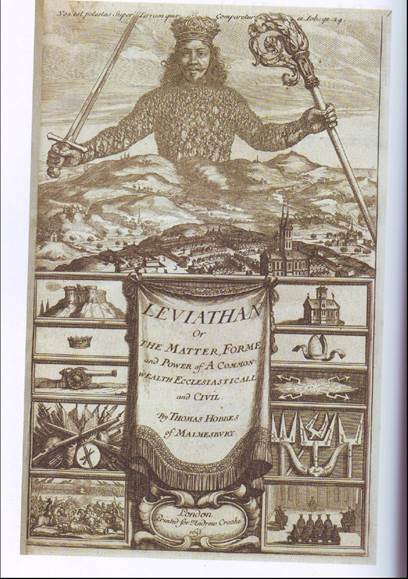

CG: Hobbes is often regarded as a crucial figure of modernity -a notion that I never use, since in my view it is devoid of any analytic value. I would prefer to rely upon a different category -secularization- which I tried to redefine in my book. By secularization, I mean a long-term historical phenomenon, which is developing under our eyes, and is far from being over. Secularized power -first of all, the power of the State- invades the domain of religion, using its weapons as instruments of control over people. The most important of those weapons is fear (fear of God, fear of death). But fear of God must be read in reverse: Primus in orbe deos fecit timor, as the Latin motto read, i.e. what first created gods in the world was fear. The front page of Hobbes's Leviathan1 displays the image of a giant -the State, that "mortal God," as Hobbes said- holding a sword in one hand, the pastoral in the other. This appropriation of the weapons of religion is what I meant by secularization: a violent phenomenon, even if this violence often takes place only at a symbolic level. Our world is not, pace Max Weber, a disenchanted world: on the contrary.

Needless to say, the resistance to secularization does not justify the horrors that are perpetrated, every day, in the name of religions. You know the French dictum: tout comprendre c'est tout pardonner, to understand all is to forgive all. I hate this dictum; I regard it as absolutely wrong. We must try to understand; to forgive or not to forgive is a completely different matter.

RS: Professor Ginzburg, your text on Hobbes begins and ends with a proposal regarding the relations between the past and the present and therefore, it seems to me, on the relationship between historians and politics. Perhaps echoing your own idea of the role of distance in (historical) analysis, you point out that in order to talk about the present, in certain cases it is best to turn our eyes back to the past. What exactly is your idea of the relationship between politics and historical analysis?

CG: We live fully immersed in the present -but this full immersion often paves the way to a feeling of false familiarity. We should try to counteract this feeling, distancing ourselves from the present. To achieve this aim we may rely upon different strategies; looking at the past is one of them, since it may help us to look at the present obliquely, in a non-literal way. But not even the present is a self-evident category. In every fragment of the present, multiple pasts are inscribed, encrusted and superimposed.

The relationship between the present and the past is complex. We should refrain from relying upon empathy -that fashionable, and utterly misleading notion. Empathy assumes that we can identify with other people who belong to a world that is distant (either in space, or in time, or both) from ours. My approach is different. The questions we ask of the past (or of a different culture) are -I would argue- inevitably born of the present, of our culture: they are either anachronistic, or ethnocentric, or both. The questions we address to the past are affected by our assumptions, our biases, our prejudices; they are inevitably impregnated with politics. But this is only the beginning. Through a long, sometimes difficult process we can learn the language spoken by those distant actors (once again, distant either in terms of time, in terms of space, or both). But as we all know, distance between different actors can exist even within the same society: a troubling, sometimes extremely painful experience. But distance can generate knowledge: a necessary ingredient of both history and politics.