Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Colombiana de Psicología

Print version ISSN 0123-9155

Act.Colom.Psicol. vol.16 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2013

ARTÍCULO

DOI: 10.41718/ACP.2013.16.2.8

STRATEGIES TO RECONCILE DOMESTIC AND PAID WORK DUTIES IN MEXICAN POLICE WOMEN: A STEPPING STONE TO GENDER EQUALITY?

ESTRATEGIAS UTILIZADAS POR MUJERES POLICÍAS PARA CONCILIAR SUS DEBERES DE TRABAJO DOMÉSTICO Y REMUNERADO: ¿UN CAMINO HACIA LA EQUIDAD DE GÉNERO?

ESTRATÉGIAS UTILIZADAS POR MULHERES POLICIAIS PARA CONCILIAR SEUS DEVERES DE TRABALHO DOMÉSTICO E REMUNERADO: UM CAMINHO RUMO À EQUIDADE DE GÊNERO?

OLIVIA TENA*

NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO, INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH CENTRE FOR SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES, MEXICO, D.F., MEXICO

* The manuscript is based on data from the project "El impacto del trabajo en el empoderamiento de las mujeres que laboran en el espacio de la policía: El caso de la Secretaría de Seguridad Pública del Distrito Federal" supported by grants from the Project Support Program for Research and Technological Innovation IN307810 (PAPPIIT IN307810 for its Spanish acronym) from the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The author gratefully acknowledges students and academics from the Research Group about Police Women (GIMP for its Spanish acronym), for their assistance with data analyses and with data collection activities. The author also acknowledges the Federal District Ministry of Public Security (SSPDF for its Spanish acronym) for its logistic support for the data collection tasks. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Dra. Olivia Tena, Centro de Investigaciones Interdisciplinarias en Ciencias y Humanidades, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Torre II de Humanidades, 5º piso, Ciudad Universitaria, México, 04510, D.F. tena@unam.mx

Recibido, septiembre 1/2013Concepto de evaluación, octubre 2/2013

Aceptado, noviembre 20/2013

Referencia: Tena, O. (2013). Strategies to reconcile domestic and paid work duties in Mexican police women: A stepping stone to gender equality?. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 16 (2), 81-91.

Abstract

This study examines the experience of Mexican police women regarding their strategies for reconciling paid employment and family life from a gender perspective and explores some individual and structural experiences about work-life related preferences. Double presence, understood as the need to respond simultaneously to the demands of paid and domestic-family work, affects mostly women and may negatively affect their health, so it is important to analyze its different manifestations in working women whose jobs have prolonged and atypical work schedules such as police officers. Mixed (quantitative-qualitative) methods were used, so that first questionnaires were applied to police women and men with operative ranks and the same was done with women who had a command rank. After that,, women with both police ranks were interviewed in order to delve into some quantitative indicators related to gender inequalities in the division of labor. Results showed gender inequities in the way women and men arrange their work and family life. These inequalities result in individual informal conciliatory strategies that derive in an increases in women's workloads. The specificity of the police institution is discussed as well as the prevalence of the needs of police women in the way they make their choices for the reconciliation of family and employment. Finally, the importance of institutional policies that allow free choice in women is revealed.

Key words: Police women, gender equity, double presence, job-family reconciliation.

Resumen

Este estudio examina la experiencia de las mujeres policías en México acerca de sus estrategias para conciliar el empleo remunerado y la vida familiar desde una perspectiva de género y explora algunas experiencias individuales y estructurales relacionadas con sus preferencias sobre el trabajo y la vida. La doble presencia, entendida como la necesidad de responder simultáneamente a las exigencias del trabajo remunerado y doméstico de la familia, afecta sobre todo a las mujeres y puede tener un impacto negativo en su salud, por lo que es importante analizar sus diferentes manifestaciones en mujeres que trabajan en empleos con horarios de trabajo prolongados y atípicos como agentes de policía. Se utilizaron métodos mixtos (cuantitativo-cualitativos), por lo que primero se administraron cuestionarios a mujeres y hombres policías con rangos operativos y a mujeres con rangos de mando en la institución. Posteriormente, se entrevistó a mujeres con ambos rangos policiales con el fin de profundizar en algunos indicadores cuantitativos relacionados con las desigualdades de género en la división del trabajo. Los resultados muestran desigualdades de género en la forma en que mujeres y hombres organizan su trabajo y vida familiar. Estas desigualdades dan lugar a estrategias conciliatorias informales individuales que derivan en un aumento en las cargas de trabajo de las mujeres. Se discute la especificidad de la institución policial, así como la prevalencia de las necesidades de las mujeres policías en la manera en que toman sus decisiones sobre la conciliación entre familia y trabajo. Por último, se releva la importancia de diseñar políticas institucionales que permitan decisiones libres en las mujeres.

Palabras clave: Mujeres policías, equidad de género, doble presencia, conciliación vida laboral-vida familiar.

Resumo

Este estudo examina a experiência das mulheres policiais no México sobre suas estratégias para conciliar o emprego remunerado e a vida familiar desde uma perspectiva de gênero e explora algumas experiências individuais e estruturais relacionadas com suas preferências sobre o trabalho e a vida. A dupla presença, entendida como a necessidade de responder simultaneamente às exigências do trabalho remunerado e doméstico da família, afeta sobretudo às mulheres e pode ter um impacto negativo na sua saúde, por isso é importante analisar suas diferentes manifestações em mulheres que trabalham em empregos com horários de trabalho prolongados e atípicos como agentes de policia. Utilizaram-se métodos mistos (quantitativo-qualitativos), primeiro foram aplicados questionários às mulheres e homens policiais com patentes operacionais e mulheres com patente de comando na instituição. Depois, foram entrevistadas mulheres com ambas patentes policiais com o objetivo de aprofundar em alguns indicadores quantitativos relacionados com as desigualdades de gênero na divisão do trabalho. Os resultados mostram desigualdades de gênero na forma em que mulheres e homens organizam seu trabalho e vida familiar. Estas desigualdades permitem estratégias conciliatórias informais individuais que derivam em um aumento nas cargas de trabalho das mulheres. Discute-se a especificidade da instituição policial, bem como a prevalência das necessidades das mulheres policiais na maneira em que tomam as suas decisões sobre a conciliação entre família e trabalho. Por último, é mostrada a importância de criar políticas institucionais que permitam decisões livres nas mulheres.

Palavras-chave:Mulheres policiais, equidade de gênero, dupla presença, conciliação trabalho-vida familiar.

Introduction

Fifty years ago, Betty Friedan wrote "The Feminine Mystique". This book favored the resurgence of the feminist movement in the 1960s, also called the Second Wave. Its impact was due to the fact that many women transformed their personal awareness through reading it. Friedan, on the other hand, is forerunner in documenting and putting words to "the women's malaise", the problem that was not named because it had no name; in her book, she revealed the identity of women as housewives in the post-World War II years, which although well-rooted, showed contradictions with the true wishes of middle-class women in the United States. However, the problem she posed was not exclusive of these women, so the book traveled the world and it won the Pulitzer Price.

This paper analyzes the subject at hand by starting with the contributions of this feminist author, who had as one of her political objectives the attainment of equality of women and men in a mainly professional sense, for which it was necessary to put aside the obstacles that prevented it, such as domestic work, which, she proposed, could be delegated to professional domestic workers.

As is clear from what was said above - and as was pointed out by Mary Goldsmith (2005), Betty Friedan did not question yet the sexual division of labor within households, or the historical gap between the so-called public and private scope, by suggesting strategies - almost personal - to remove obstacles and facilitate the discharge of women in the labor market, thus delegating the domestic arena to other women who, although she did not point it out, would also carry out domestic work, now for pay, and would require finding strategies for doing domestic work in their own homes and for the care of children, in a endless chain.

However, we must recognize that, lacking other cultural, political and social resources, women in history - who, by the way, have always worked - have made use of personal strategies, almost always of solidarity with other women and with no pay involved, to tackle what has been called "double workday" and which in 1979 the Italian sociologist, Laura Balbo, called "double presence" in a brief essay titled La doppia presenza. The double presence in women's lives implies something more than having different jobs in different and separable workdays.

The concept of double presence recognizes women's double work load, although performed in the same space, time and workday, with all what this implies in terms of the malaise generated, by not modifying substantially the sexual division of labor (Carrasquer, 2009). The double presence as an analytical framework allows observing, among other things, the strategies that women generate to face the demands for presence and availability established by both paid and unpaid work, including domestic work, as well as family management and care in the latter.

This confirms the importance of analyzing the double presence of women by considering the different ways of articulating their spaces and times by meeting particular labor demands. I focus on one singular type of job of recent female incursion, the one carried out by women in police corporations, with the objective of exploring their strategies to face the demands for double presence, which imply a daily effort to reconcile family and work life. The double presence, as is clear, is not an attribute of women in the police force, since, taking up again what Betty Friedan suggested, there is a malaise or a problem that is common to women, beyond individual duties.

Although Friedan described this malaise with regards to middle-class women in the United States, it can also be identified in the majority of women with a double workday. The common demand for double presence in women, contemplates being good mothers and making sure that all daily issues of the household function properly. All these demands are without consideration of the economic contributions obtained because of an extra-domestic work, whatever it is. However, in referring and looking mainly to women who work in the police, it is necessary to stop and explore their particular working conditions, to emphasize the specific ways in which they experience the double presence and its associated uneasiness and welfares therewith.

In this sense, this paper explores the "conflict of duties" (Tena, 2006) between spaces, times and workdays, to finally analyze some strategies to reconcile and the subjective malaises that women experience, with regards to their work in the police, all of these taking into consideration the simultaneity of work in space and time by exercising a double workday.

The article is divided into three distinct parts: in the first part, the analysis of the theoretical framework is presented in order to approach the debates that have arisen from feminist theories around the concept of "reconciliation" in reference to the family and work spheres. Next, the discussion focuses on the police institution, its singularity and the life situation of women who function as police women. In the last part, the general project that serves as framework to this study is presented, as well as some of the results obtained from the analytical framework of double presence.

The concept of reconciliation

The concept of "reconciliation" within this thematic context refers to a need to harmonize the time devoted to work and family life, a problem that has been defined primarily as feminine, which is why the efforts in this sense have been directed mainly and mistakenly to women, through actions, whether individual, institutional or state, that generally reproduce the social representations of women as housewives and caretakers because of their "innate" qualities. This has resulted in labor policies that refer exclusively to women and, as an example, we have part-time contracts - also with half salaries -, designed to enable women to fulfill their family obligations, which at the same time reflect and reproduce gender inequalities.

The reconciliation of family life and labor life has been widely studied by social psychology and by other disciplines such as sociology and economy. Their analyses are inserted into the study field about the work-family conflict. Torns (2011) is right in asserting that this conflict has existed since work was conceived under the discipline imposed by industrial capitalism in the 19th Century, affecting the salaried population but particularly women, by fixating a time related to work. In this sense, the reconciliation would not be anything more than a new way of naming an unresolved old problem (Carrasquer, 2009).

The Preferences Theory (Hakim, 2005, 2006) suggests that strategies and attitudes toward work are the result of one's own values and preferences of women about their lifestyles, more or less adjusted to gender norms. To capture these preferences, Hakim identified three groups, taking into account the priority given to family and employment: 1) No particular preference; 2) a greater preference for work space and time, and 3) a greater preference for family space and time. For this author, the strategies adopted depend on the type of dominating preference in each case and, therefore, concludes that women construct their labor biographies in relation to their individual decisions, but based on such preferences.

Other explicative models of greater complexity show results that contradict the preferences model; these complex models have proven empirically that the strategies adopted by mothers at the care and domestic work, in relation to employment, depend more on the institutional and structural conditions than on the individual gender norms and values, with the participation of males being an important predictive factor.1 Crompton and Lyonette (2008) found that the main factors that determine the strategies for reconciliation, in relation with child care, were the structures that provide opportunities and limitations faced by parents involved, which constrain choices for women.

The importance of these findings lies in realizing that women could use strategies to cope with the double presence without necessarily reflecting their attitudes and preferences on how to organize their life time, by not having the resources to do so. In Spain, for example, it has been found that most women who resort to the part time employment model do it because they have not found a full-time paid job or a strategy to deal with the double presence (Alcañiz, 2012).

On the other hand, it is worth reflecting upon the meaning of reconciliation as a strategy, since it implies a sort of adaptation to the gender norms, although it might not necessarily coincide with the person's wishes. The reconciliation as a policy has involved the search for strategies to enable women to continue performing occupationally without neglecting their family responsibilities, so this does not imply any change in the sexual division of labor and does increase women workload, generating malaise and sickness.

Public policies need to recognize the importance of rejoining a language that affirms the women rights to co-responsibility about domestic and caring work. This co-responsibility should be promoted in conjunction with their couple, whenever there is one, but ideally with the participation of the institutions where women work and of the State itself, since it is impossible otherwise. Based on this, it is important to analyze the individual strategies of reconciliation and co-responsibility, in light of the labor institution where women participate, which in the case at hand has peculiarities both in its structure, internal norms, hierarchy and representation: police institutions.

Double presence of women in the police force

The public space, in general, has been constructed by men and for men; it has been regulated and designed, in its structures and practices, based on hierarchies, competition and power, characteristics that do not match with what is still considered proper to femininity. Even so, women have entered into these spaces, displaying resistance but also in many cases adapting to those masculinized norms, structures and practices, in the sense of having been constructed throughout time under the assumption of a sexual division of labor.

Particularly, police work was conceived for and by men since its origins, which makes its cultural dissonance even more clear when women enter their ranks. Incorporation of women into the police force could appear to be dissolving gender barriers; this could be interpreted by observing that women can carry out virtually any type of activity in the police forces. However, there are still barriers, some of them structural and others derived from gender stereotypes, when conceiving women as lacking the character or traits that naturally make men efficient in these activities that require courage and fearlessness.

The police force is certainly a strongly gendered institution, in the sense that its gender norms construct a kind of masculinity that highlights certain values such as domination, competition, strength, sexism, homophobia and misogyny, among others, in addition to having hierarchy as an important gender differentiator.

Within police norms, there is one related to the definition of work and use of time in male terms. Implicitly, the labor model of the breadwinner is taken for granted, since it has been the pillar upon which police work has been traditionally organized. These male-dominated work cultures have proven to be an obstacle reported by women as an explanation of their release from police institutions (Cordner & Gordner, 2011).

Research about women who carry out paid work in police institutions is very scarce in Mexico (see Arteaga, 2000; Suárez, 2006; López, García & Sánchez, 2013; Tena, et al., in press), so most of the theoretic and empirical references here are derived from studies of other countries.

Most recent gender studies on this subject can be divided into two groups: 1) Those that study the incorporation and performance of women within police institutions emphasizing adaptation and resistance to masculine norms (see Suárez, 2006; Rabe-Hemp, 2008; Morash & Haar, 2012), and 2) those that broaden the work concept to the domestic and care work, which allows analyzing the impact of the double presence in different dimensions of the work of women in the police force. Within the first group, there is a tendency to focus on analyzing the relationship between the organization and the women who work there, neglecting the fact that this relationship is mediated by multiple family demands under an implicit understanding that there would be an adaptation of such complaints to the organizational requirements.

Therefore, strategies to reconcile work and family life in the double presence analysis framework have not been sufficiently addressed. For this it is essential to incorporate a broad sense of the concept of "work" to examine the tensions between work and family obligations of police women. This line of research has been gaining importance in recent years, with significant findings that can be interpreted in light of the discussions described above around the Preferences Theory (Hakim, 2005, 2006; Crompton and Lyonette, 2010).

Overall, the difficulty for women to combine caretaking and domestic work with the demands for availability in the police force has been documented, as well as their changing preferences with regards to the desire to advance in the police career and the desire to focus more on their family life. Previous studies have already shown that one of the major causes explaining the exit of women from the police forces of Canada had to do with their domestic workload (Seagram & Stark-Adamec, 1992) and more recently Maureen O'Hara (2009) found that in Ireland, women were limited in their chances of promotion in the police largely by their self-exclusion of these processes, because of adaptive preferences that took them to focus more on their caring responsibilities at home.

Chan, Doran & Marel (2010) meanwhile, found that most women had changed their gender practices and preferences over the years. Initially, as Australian police recruits, they were more focused on work, but those who took on parenting responsibilities began to accept a form of sexual division quite similar to the traditional. These results were confirmed when women had small children, in contrast with those who didn't have children or these were grown up (Bochantin & Cowan, 2010).

In terms of strategies to face the double presence, research is even more scarce in relation to this kind of job, although different strategies have been documented when women are in conditions to negotiate with their children's fathers and, even so, the strategies imply, most of the times, costs in terms of free time and hours of sleep (O'Hara, 2009). In this sense, inequality in the use of time for women who work in the police is also an important reference in relation to the strategies implemented (see López, García & Sánchez, 2013).

Based on the reported studies and in the interest of having a deeper approach to the strategies used by police women in Mexico City to meet the demands of the double presence, considering both structural and individual factors, this analysis is presented. Data are the product of a broader feminist study with mixed methodology coordinated by the author and entitled "The impact of work on the empowerment of women in Mexico City's police force", which was held at the Ministry of Public Security of the Federal District (Secretaría de Seguridad Pública del Distrito Federal, SSPDF, for its Spanish acronym). This study was designed with the general objective of exploring the impact of women's insertion into the police force on their empowerment, paying attention to family and work domains and also to differences in sex and hierarchy, using a combination of qualitative and quantitative data.

Some methodological dilemmas and the potential of this type of mixed approach have been discussed in the light of feminist research on the basis of their unwillingness to accept quantitative methods. It was said that these methods reinforce the androcentric scientific paradigm, which usually distorts women experiences and mutes their own voices (see Jayaratne & Stewart, 1991). Some feminist authors also criticized the goal of conventional objectivity and value-neutrality in these dominant sciences (Harding, 1993) and feminist objectivity was described as "situated knowledge" (Haraway, 1988). Under these arguments, mixed methods may represent an erroneous combination of techniques derived from incompatible scientific and political paradigms. Nevertheless, it was also asserted that there is no such a thing that qualifies a method itself as feminist, so researchers should use any method depending on the question asked under feminist insights (Harding, 1987; Stanley & Wise, 1993). This methodological frame surrounds the present work and stands that mixed methods, which incorporate both quantitative and qualitative techniques, have particular value under the complex social contexts that constitute the daily experience of women dealing with patriarchal police institutions and with family affairs. This research uses a transformative sequential mixed design to explore de double presence of women in the police institution.

Method

Participants

The study population that participated in a first (quantitative) phase consisted of 1064 officers from the SSPDF in Mexico City. Among them, 500 were women working in an operational area (Operative Women), 75 were women with a high-ranking position (Command Women) and 400 were men from an operational area (Operative Men).

Table 1 shows some demographic data of the three groups. Similarities were observed in the average age of all groups. Regarding their schooling, the majority of women with a command rank had high school and undergraduate university studies, while women and men with operative ranks in their majority reported maximum studies of secondary school. Command women also reported more years in service than operative women and men.

In relation to their situation of cohabitation, 55 % of operative women and 67 % of command women, reported living without a partner, whether in an unmarried, divorced or widowed condition, in contrast with operative men from whom only 16 % reported the same situation. It is worth mentioning that among those who reported living in singleness, 32 % of operative women, said they had children, in contrast with 4 % and 0 % of command women, and operative men, respectively.

During a second (qualitative) phase 8 operative women and 9 command women, from the SSPDF were involved. All of them had participated in the first phase, had given informed consent to go on to the next stage and had provided their location data.

Equipment and materials

- Quantitative phase

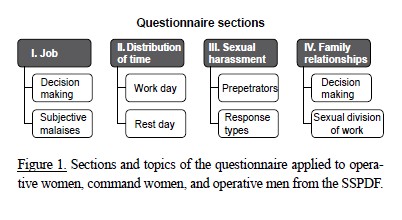

We designed a self-administered questionnaire composed of four sections, each of which represents an area to explore, each with two topics (Figure 1). For the purposes of this paper, data were analyzed on the "Sexual Division of Labor", while are also are considered "Distribution of Time" and "Subjective Malaises".

- Qualitative phase

This second phase was carried out with a semi-structured interview guide based on the results of the questionnaire and on the theoretical framework that guided the general research.

Procedure

From a stratified intentional sampling, a fraction of 5 % (517) of women was taken, out of a total of 36,295 who worked at any operative area of the SSPDF police, among which a participation of 449 was obtained. The same number of men was requested from the same area, among which a participation of 473 was obtained. Each of the operational areas in the SSPDF is divided into sections and an equivalent sample of each one of them was taken. The participation of 100 % (74) of command women was also requested, obtaining the participation of 71 of them.

- Quantitative phase

The questionnaire was applied in groups of 30 people in a training classroom from the General Management of Human Rights of the SSPDF. All the participants were informed that their collaboration was voluntary as well as confidential, indicating that they had the right to refrain from answering the questionnaire. After applying it they were asked for their voluntary consent to collaborate in the next stage and, if they accepted, to fill out a format where they stated so and added their localization data, assuring them that this information would also be confidential.

- Qualitative phase

It had the aim of delving into the police women's trajectories throughout their family and labor lives, recognizing their diverse experiences in times and spaces institutionally shared, and identifying their particularities. The analysis is based on both descriptive and procedural categories, related to parenting and domestic work, framed within an institutional context. Participants in this phase were randomly selected among those who expressed their consent and then were located by telephone. Interviews lasted about two hours and were conducted with each participant on one or two days, and at the place indicated by them, usually in restaurants nearby their job site in Mexico City.

Results

Some results about double presences and possibilities of work-family reconciliation in police women are presented below. Recovering demographic data presented in Table 1, it is clear that there is an unequal distribution in the lifestyles by sex and rank. Those with higher ranks, command women in this case, showed higher levels of income and schooling, which, according to the literature, is associated with a greater ease to reconcile domestic and child-care duties with employment (see Ábramo, 2004). Besides, higher incomes are frequently associated with labor motivations that give priority to independence and personal fulfillment, which make it possible for women to have greater chances of negotiation and also allow them to recruit other women who provide help in household chores, as was told by the following high-ranking policewoman:

Regarding the tasks, yes, house chores are distributed. Yes, there is a person who helps us twice a week and the other days everyone washes their clothes (high school education).

It is also observed that a high percentage of police women, regardless of their rank, live without a partner and this could be an indicator of incompatibility of this type of job with living as a couple for different reasons, some of which were described by police women:

a) Competition of men with their police wives when faced with the fact that these women had advanced in terms of income and rank:

...my second marriage, my son's father, it was as if he felt less because I earned more. That is: "How is it possible that you earn more being a cop?"... Yes, it's as if they felt inferior. And my last partner... well... much more. I felt that he was going to feel at a lower level because I had a higher rank (High-ranking woman, divorced).

b) Incompatibility of time demands from the partner with the labor time of policewomen:

...because, for example... wanted time to go to the movies, to have a coffee, have sex, things like that, right? (laughs) (High ranked police woman divorced).

c) Awareness of gender inequality at an evident unequal distribution of domestic work:

In fact I was commander of him, then he used to come and come straight to sleep and, so I didn't; I mean, the fact that I got home to relieve my mother, well I didn't sleep, so, it's like if I told myself: "Well, if I charge my batteries and all, why doesn't he?". ... because I felt that, well if I put the kilos with the girl and I came home and, I mean, we both worked, we both had the same schedule, that is, equally tired, so ... yeah, I told him 'Well, you know what?, better already get outta the house , really, I think it would be better. (Operative woman, separated).

This story shows the low negotiating power of the woman with her partner, although in the labor sphere she is the one who has a position of authority over him. Here, we can clearly see the exercise of two powers that are played at different spaces and times: the symbolic gender power and the institutional power based on hierarchy. In contrast, the high percentage of police men living with a partner gives men an advantage, both in work and life, because of the type of power that they feel legitimized to exercise in the household space. This implies the security of having a person - his wife or partner - who, with extra-domestic work or without it, takes on the domestic and caretaking tasks.

Conversely for police women as shown by the last testimony, living as a couple can be experienced even as one more element to face under their double present condition, which hampers their already difficult effort to harmonize their family and labor domains. It can be said that these women experience it as a third presence when facing partners who demand more presence and generate more work in the household.

The testimony of this command woman also shows us two conciliation strategies documented in the literature and often found in our interviews: Breaking away from the couple and getting support on the solidarity networks with other women, in this case the mother, in others the sisters and sisters-in-law, and in other cases, going through the physical separation from their sons or daughters:

And my daughter, well she had to be cared by my sister -my other sister who lives at Veracruz-, so I can get ahead; I mean, even I had her in boarding schools, for my daughter to be cared, therefore, by people, I mean, I jumped until I found a good boarding school (Operative woman).

Another high-ranking woman told us the following, referring to the difficulties of women with partners to gain access to higher positions and have a good performance:

...the structure2, that is, you earn more but you have to be there more time... Even if they had a partner, they sometimes said: "But my husband doesn't agree". Others said "Let me check it with my husband"... Then they talked it over with him and they said: "Yes boss, come on, since it's an extra little cent"...

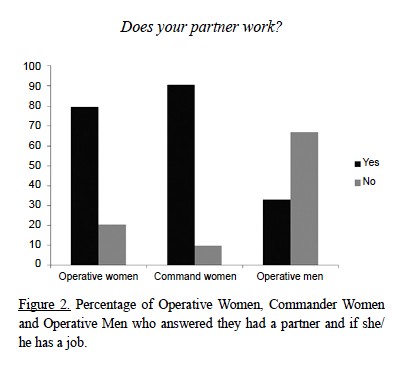

Differences in life in relation to work and family are also seen in Figure 2, which represents the percentage of operative and command women who form double income couples (Dema, 2006), compared with men. These data show that the latter in most cases, keep the representation and practice about women dedicated entirely to the home and the man as the sole supplier.

In this graph it is noteworthy that higher percentages of lower-ranking women reported having a partner who didn't work (20%), compared with command women (10%), which suggests that maybe the husband's unemployment motivated them to enter this type of job. While this issue was not documented through our interviews, we did find women's narrations, which highlighted the salary supplement as motivation for entering police work, without questioning the unequal distribution of work:

Because I told him: "I think that having started to work it was to improve our financial situation, to help you because you have the obligation to provide everything" (Command woman, separated).

Who is responsible for the domestic work?

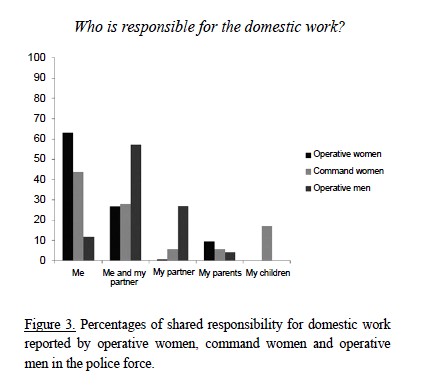

Although an equivalent percentage of men and women, regardless of rank, reported having children (Table 1), this is not reflected in what they report in terms of dedication of one or the other to domestic work (Figure 3). Women in general and operative women outstandingly were the ones who, in greater percentage, responded that they alone are in charge of it. On the other hand, most men (57%) defined themselves as co-responsible for domestic work in their households and an important percentage of women (27% and 28%) also referred so. This can be explained, in first instance, by a bias from the characteristics of the population, where, as we have analyzed, men in their majority are in a cohabiting relationship in contrast with women.

Even so, it is important to analyze the meaning that women give to the co-responsibility of men, taking into account the findings of gender studies (see Larrañaga, Arregi & Arpal, 2004; Pedrero, 2004), which point out that men devote fewer hours to domestic work compared to women, and that the kind of tasks that men carry out are also different.

According to these studies, men focus mainly on maintenance and management of household services and also, but in a lesser extent, to the care of children. This, in terms of gender inequity, implies that they do not negotiate, but rather decide to undertake the most gratifying and less committed tasks, in terms of time and effort. Men's participation, even under these disparities, is often misinterpreted by police women as co-responsibility in the household chores:

-Hey, and your husband, what did he do?

-He worked... Yes, he helped me... Well, at least to take care of the children... and with the house chores too.

-Whose responsibility was that? Yours or his?

-Errr... I think it was shared by both of us.

-Do you think that the responsibility was in fact equally divided?

-Hmmmm... [she nods] ... Check in time was at 9... I got up at 5:30, collected the milk from the creamery and came back to prepare breakfast for school, what the children took to school. I took one of my girls to the daycare... my boys to the elementary school... and I came back to prepare my things and left... but when I left the food was already made. The father, he arrived and fed them. And I arrived at 5... washed, prepared and planned what I would cook to eat... Everything, homework, school meetings...

-Did he stayed home to carry out some activities?

-Homework... In the morning he also helped me to clean up.

-And that's it, to put the children to sleep. And you?

-Well, let's see... the ironing. ( Woman Commander describing her activities when she had 4 small children, worked as a policewoman and lived as a couple).

This last narration, frequent among the women interviewed, allows us to see the importance of studies about the use of time among women who work in the police force, as basis for the design of labor policies that seek gender equity, taking into consideration that double presence is very common in those spaces, given the extended hours of work that they have. A pioneering research in this area is that of López, García & Sánchez (2013). It derived from the general research from which this study also stems, whose data refer to the same population analyzed here.

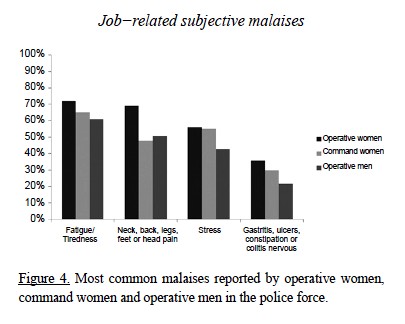

It is worth noting what the authors found in relation to the days off. During these, there are more hours of leisure in men and unpaid work in women, compared with the days of police work, which is an important indicator of gender inequality in their homes. These data, in addition to those exposed in the present paper, result in a greater amount of malaises perceived by women compared with men, related to their work in the police (Figure 4). This graph shows that a higher percentage of operative women reported malaises compared to the other two groups in each case. They were followed by command women and in the last place by operative men.

Finally, the following description of a typical operative woman sums up the feeling of the double presence and solidarity among women, all of which is shared in some way by the women of the police force.

... And I do not allow myself to fall into depression or anything like that ... but I say that these are many problems that one has both at home and at work and they add up. Yes, because I do know many of my girlfriends who feel bad or are exhausted, then I tell them: "You are exhausted, so take this or get a shot of Bedoyecta or the other" ... Among us we give advice to each other, "Do it like this or do it like that, or take your child to that place", or so, we go on giving advice, and I think that is because we have two jobs and men only have one job, they work and come home and they give orders: "Give me my dinner!, feed me!"

Discussion

This study explored, from a feminist gender perspective, some strategies to reconcile work and family life in women who work in Mexico City's police force, with emphasis on their preferences, needs and obstacles to deal with the double presence (Balbo, 1979), and in some malaises that could be related to them. Questionnaire/interview data were obtained from a mixed method research design, applied to police women of lower and higher ranks in the institution and also to men of lower ranks.

Findings show that regardless of rank, police women experience tensions emanated from job-family conflicts trying to deal with the cumulative demands corresponding to these two different domains, with overlapping time periods, which can hardly be detected through time use surveys (López, García & Sánchez, 2013).

Even so, police women's lack of formal structural support to face such conflicting job and family demands, leads them to use strategies according to the resources available, and here we can see some differences in the light of their particular life situations. These resources, as expected, are conditioned by the level of income associated with the women's rank, facilitating either hiring a person to take charge of domestic work in those of higher hierarchy, or forcing to sacrifice sleep hours to fulfill the duties in those of lower hierarchy and income.

The latter, which we interpret not just as a difference but as some kind of inequity indicator in terms of resource availability, was reflected in a greater perception of malaises in women of lower rank and in women in general in comparison to men with operative work. Men usually have as a greater resource their own spouses and mothers of their children, as a police woman suggested.

All of this shows that some strategies displayed by women with fewer material resources are more adjusted to their needs than to their personal choices, so it is not surprising that most of them, when they have children, organize their time and space, giving priority to the nurturing, caring and domestic work, with its continuous demands for presence and time. But the axis of all these activities is the daily workload assigned by the police institution, whose timetable tends to be atypical, in the sense of demanding the presence of women of lower ranks for 12 or 24 continuous hours. High-ranking women, on the other hand, although enjoying more material resources, ought to be available to work 24 hours a day and this could be related to their tendency to have fewer experiences as mothers and cohabiting partners.

The operative police men may be more easily adapted to the institutional work days, given the prevalence and still naturalized sexual division of labor, present in norms and practices of the police and family institutions. This has been documented in police institutions and in other labor scenarios (López, García & Sánchez, 2013; Tena, Rodríguez & Jiménez, 2010).

Another important finding was that most women reported living without a partner, in strong contrast with men. This led us to deepen its meaning, and we found what we have called a possible "triple presence", which adds another duty in the case of women who live as couples, which implies meeting the demands of time and space expected by their partners, and a greater amount of domestic work derived from the fact of sharing the same living space but not sharing the responsibility for the work associated with it.

The finding of this triple presence allowed us to identify one more strategy for reconciliation, which consists of separating from the partner, which in turn explains the higher number of operative women without a partner and with children. It is worth mentioning the importance of feminine solidarity networks associated with reconciling strategies of double present women in the police. This is a resource under-explored in the literature, which is worth deepening in future studies.

Although the objectives of this paper did not attempt to present a generalization of the results for the whole universe of the police population in Mexico City, the findings provide important feminist keys to consider, when suggesting labor policies aimed at achieving greater gender equity in these organizations. We think that the false quandary regarding the importance of structural or individual factors on the decisions that women make in terms of double presence, can be redefined in the light of exploratory studies with mixed methodology such as the one presented here, whose results suggest the importance of promoting structural, cultural and social transformations, so that the reconciliation strategies are not meant only for women, but these can be exercised on a shared preference. Nowadays women's individual strategies to reconcile family and work duties are not safe stepping stones towards gender equity. We can finally conclude, remembering Betty Friedan, that the malaise of women is not just the problem of women.

1 To review these works, see Moreno (2010). Volver

2 "Structure" is as it is called the management positions within the police. Volver

References

1. América latina: ¿Una fuerza de trabajo secundaria? Revista Estudios Feministas, 12(2), 224-264. [ Links ]

2. Alcañiz, M. (2012). Relaciones entre la producción económica y la reproducción social en tiempos de crisis: Identidades y roles de género en transformación. En: G. Escrig, M. J. Ortí & R. Beltrán, Actas del VIII Congreso Estatal Isonomía sobre igualdad entre mujeres y hombres. El Género de la Economía o la Economía de Género (pp. 58-68). Universitat Jaume: Fundación Isonomía. [ Links ]

3. Arteaga, N. (2000). El trabajo de las mujeres policías. El Cotidiano, 16 (101), 74-83. [ Links ]

4. Balbo, L. (1979). La doppia presenza. Inchiesta, 32, 3-11. [ Links ]

5. Bochantin, J., & Cowan, R. (2010). "I'm not an invalid because I have a baby...": a cluster of analysis of female police officers experiences as mothers on the job. Human Communication, 13(4), 319-335. [ Links ]

6. Carrasquer, P. (2009). La doble presencia: El trabajo y el empleo femenino en las sociedades contemporáneas. Barcelona: Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. [ Links ]

7. Chan, J., Doran, S., & Marel, C. (2010). Doing and undoing gender in policing. Theoretical Criminology, 14 (4), 425-446. [ Links ]

8. Cordner, G. y Gordner, A. (2011). Stuck on a Plateau? Obstacles to recruitment, selection and retention of police women. Police Quarterly, 14 (3), 207-226. [ Links ]

9. Crompton, R., & Lyonette, C. (2008). Family, class and gender "strategies" in mothers' employment and childcare. En: J. Scott, R. Crompton & C. Lyonette (Eds.). Gender inequalities in the 21st century: New barriers and continuing constraints (174-192). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

10. Dema, S. (2006). Una pareja, dos salarios. El dinero y las relaciones de poder en las parejas de doble ingreso. Madrid: CIS. [ Links ]

11. Friedan, B. (1963). The Feminine Mystique. New York: Dell Publishing. [ Links ]

12. Goldsmith, M. (2005). Análisis histórico y contemporáneo del trabajo doméstico. En: D. Rodríguez & J. Cooper (Eds.), El debate sobre el trabajo doméstico (pp. 121-174). México: UNAM. [ Links ]

13. Hackim, C. (2005). Modelos de familia en las sociedades modernas. Ideales y realidades. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. [ Links ]

14. Hackim, C. (2006). Women, careers, and work-life preferences. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 34 (3), 279-294. [ Links ]

15. Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599. [ Links ]

16. Harding, S. (1987). Feminism and methodology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

17. Harding, S. (1993). Rethinking standpoint epistemology: What is "Strong Objectivity"? In: L. Alcoff and E. Potter (Eds.), Feminist Epistemologies (pp. 49-829). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

18. Jayaratne, T. E. & Stewart, A. J. (1991). Quantitative and qualitative methods in the social sciences: Current feminist issues and practical strategies. In: M.M. Fonow & J.A. Cook (Eds.) Beyond Methodology (pp. 85-106). Bloominghton: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

19. Larrañaga, I., Arregi, B., y Arpal, J. (2004). El trabajo reproductivo o doméstico. Gaceta Sanitaria, 18(1), 31-37. [ Links ]

20. López, J., García, A., y Sánchez, J. (2013). Uso y distribución del tiempo en mujeres y hombres oficiales de policía de la ciudad de México. International Journal of Latin American Studies, 3 (1), 151-174. [ Links ]

21. Moreno, A. (2010). Relaciones de género, maternidad, corresponsabilidad familiar y políticas de protección familiar en España en el contexto europeo. España: Universidad de Valladolid, Memoria Proyecto de Investigación. [ Links ]

22. Morash, M., & Haar, R. (2012). Doing, redoing, and undoing gender: Variation in gender identities of women working as police officers. Feminist Criminology, 7 (1), 3-23. [ Links ]

23. O'Hara, M. (2009). Female police officers in Ireland: Challenges experienced in balancing domestic care responsibilities with work commitments and their implications for career advancement. Irish Journal of Public Policy, 3 (2), 11-17. [ Links ]

24. Pedrero, M. (2004). Género, trabajo doméstico y extradoméstico en México. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 19(2), 413-446. [ Links ]

25. Rabe-Hemp, C. E. (2008). Female officers and the ethics of care: Does officer gender impact police behaviors? Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 426-434. [ Links ]

26. Seagram , B C., & Stark-Adamec, C. (1992). Women in Canadian urban policing: Why Are they leaving? Police Chief, 59 (10), 122-128. [ Links ]

27. Suárez, M. E. (2006). La ruta pirata del asfalto. Trayectorias femeninas y delictivas en el mundo policial. La Ventana, 24, 250-296. [ Links ]

28. Tena, O. (2006). Los malestares subjetivos de las mujeres académicas como un conflicto de deberes. En: M, Favela y J.Muñoz (Eds.), Jornadas Anuales de Investigación 2005 (pp. 227-240). México: CEIICH, UNAM. [ Links ]

29. Tena, O., Rodríguez, C., & Jiménez, P. (2010). Malestares y uso del tiempo en investigadoras de la Facultad de Estudios Superiores (FES) Iztacala. Revista Investigación y Ciencia, 46, 64-75. [ Links ]

30. Tena, O., Aldaz, R., García, A., Espinosa, I., Avendaño, E., & Ramos, Z. (in press). Acoso sexual en mujeres policías. Del poder jerárquico al poder sexual. En: G. Vélez (ed.), Violencia de género: Escenarios y quehaceres pendientes. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [ Links ]

31. Torns, T. (2011). Conciliación de la vida laboral y familiar o corresponsabilidad: ¿El mismo discurso? Revista Interdisciplinar de Estudios de Género, 1, 5-13. [ Links ]