Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Colombiana de Psicología

Print version ISSN 0123-9155

Act.Colom.Psicol. vol.19 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2016

https://doi.org/10.14718/ACP.2016.19.1.2

ARTÍCULO

10.14718/ACP.2016.19.1.2

PROPIEDADES PSICOMÉTRICAS DE UNA ESCALA PARA MEDIR EL MANEJO DE LA VERGÜENZA EN ADOLESCENTES (MOSS-SAST)

PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES OF A SCALE TO MEASURE SHAME MANAGEMENT IN ADOLESCENTS (MOSS-SAST)

PROPRIEDADES PSICOMÉTRICAS DE UMA ESCALA PARA MEDIR A GESTÃO DA VERGONHA EM ADOLESCENTES (MOSS-SAST)

Angel Alberto Valdés Cuervo1*, Ernesto Alonso Carlos Martínez2, Teodoro Rafael Wendlandt Amezaga1, Manuel Ramírez Zaragoza3

1Instituto Tecnológico de Sonora, 2Instituto Tecnológico Superior de Cajeme, 3Instituto de Formación Docente del Estado de Sonora

* Angel Alberto Valdés Cuervo, Calle 5 de febrero 818 Sur, Colonia Centro, Ciudad Obregón, Sonora, México. Tel: 052(644)4100900 ext. 2495. angel.valdes@itson.edu.mx

Referencia: Valdés Cuervo, A. A., Carlos Martínez, E. A., Wendlandt Amezaga, T.R. & Ramírez Zaragoza, M. (2016). Propiedades psicométricas de una escala para medir el manejo de la vergüenza en adolescentes (MOSS-SAST).Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 19(1), 13-23. DOI: 10.14718/ACP.2016.19.1.2

Recibido, agosto 9/2014

Concepto evaluación, junio 18/2015

Aceptado, julio 7/2015

Resumen

Se establecieron las evidencias de validez y confiabilidad de la adaptación del cuestionario MOSS-SAST (Ahmed, 1999) para medir el manejo de la vergüenza en adolescentes ante situaciones de agresión hacia los pares. El estudio se realizó en una muestra de estudiantes de escuelas secundarias públicas (N= 700) ubicadas en un municipio de un estado del noroeste de México. Los resultados permitieron obtener un modelo de medición empíricamente sustentable formado por nueve ítems agrupados en dos factores: Reconocimiento y Desplazamiento (c2 = 5.16, p= 0.27; CMIN= 1.29; GFI= .98; CFI= .99; NFI= .97; RMSEA= .05). El instrumento cuenta con evidencias de validez de criterio, ya que establece la diferencia en los factores de reconocimiento (t= 3.49, gl= 137, p< .001) y desplazamiento (t= 3.63, gl= 137, p< .001) en subgrupos de estudiantes con y sin reportes de bullying. Se concluyó que los resultados fortalecen la estructura factorial original de la escala y muestran su utilidad, tanto en la indagación de emociones relacionadas con el del desarrollo moral, como en la identificación de estudiantes involucrados como agresores en situaciones de bullying.

Palabras clave: psicometría, vergüenza, bullying, adolescentesAbstract

This paper aimed to establish evidence of validity and reliability of the adapted version of the MOSS-SAST questionnaire (Ahmed, 1999) to measure shame management in adolescents in situations of aggression toward peers. The study was conducted with a sample of 700 students from public secondary schools (N= 700) located in a northwestern state municipality of Mexico. Results enabled to obtain an empirically sustainable measuring model formed by two factors: Acknowledgment and Displacement (X2 = 5.16, p= 0.27; CMIN= 1.29; GFI= .98; CFI= .99; NFI= .97; RMSEA= .05). Evidence was obtained to show that the instrument has criterion validity since it is capable to differentiate between subgroups of students with and without reports of bullying in both factors, Acknowledgment (t= 3.49, gl= 137, p< .001) and Displacement (t= 3.63, gl= 137, p< .001). It was concluded that the results strengthen the original factorial structure of the scale and show the usefulness of the same, both for inquiring about emotions related to moral development and for identifying students involved as aggressors in bullying situations.

Key words: psychometrics, shame, bullying, adolescent.

Resumo

Foram estabelecidas as evidências de validade e confiabilidade da adaptação do Questionário MOSS-SAST (Ahmed, 1999) para medir a gestão da vergonha em adolescentes ante situações de agressão contra os pares. O estudo foi realizado com uma amostra de estudantes do ensino fundamental e médio (N=700) de um município do noroeste do México. Os resultados permitiram obter um modelo de medição empiricamente sustentável, formado por nove itens agrupados em dois fatores: reconhecimento e deslocamento (c2= 5.16, p= 0.27; CMIN= 1.29; GFI= .98; CFI= .99; NFI= .97; RMSEA= .05). O instrumento conta com evidências de validade de critério já que estabelece a diferença nos fatores de reconhecimento (t= 3.49, gl= 137, p< .001) e deslocamento (t= 3.63, gl= 137, p< .001) em subgrupos de estudantes com e sem relatos de bullying. Conclui-se que os resultados fortalecem a estrutura fatorial original da escala e mostram sua utilidade, tanto na indagação de emoções relacionadas com o desenvolvimento moral quanto na identificação de estudantes envolvidos como agressores em situações de bullying.

Palavras-chave: psicometria, vergonha, bullying, adolescentes.

INTRODUCTION

School violence includes acts that are carried out consciously to impose or obtain something by force and causing damage to the various actors of the educational process. Bullying, undoubtedly the most serious form of violence among peers, is characterized by being systematic, by having a specific intention to inflict physical and / or emotional harm, by its relational character and by the power differences between aggressor and victim (Olweus, 1993; Swearer, Espelage, & Napolitano, 2009). This form of violence is a phenomenon long time present worldwide, as demonstrated by studies in various countries and geographical regions (Blaya, Debardieux, Del Rey, & Ortega, 2006; Eljach, 2011; Ortega, Sánchez, Ortega, Del Rey, & Genebat, 2005; Raviv et al., 2001; Robers, Zhang, Truman, & Snyder, 2012). In Mexico, the situation is not different from what has been internationally reported, since research accounts for the existence of situations of violence in Mexican schools (Castillo & Pacheco, 2008; Haro, García, & Reidl, 2013; Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación [INEE], 2007; Valdés, Carlos, & Torres, 2012; Vázquez, Villanueva, Rizo, & Ramos, 2005).

This form of violence affects the functioning of educational institutions and has an adverse effect on school social climate, since it is associated with a decrease in the quality of student learning (Allen, 2010; Collie, Shapka, & Perry, 2011; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura [UNESCO]/Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Evaluación de la Calidad de la Educación [LLECE], 2012; Román & Murrillo, 2011). Bullying, by damaging coexistence and normalizing violence as a natural form of relationship between students, affects the ultimate goal of schools, which is the formation of citizens with the skills and values that enable them to live in democratic societies (Ortega, 2010).

As the different forms of violence, bullying is a complex phenomenon that must be addressed in an ecological way by the fact that the variables related to it are located both in individuals and in diverse family, school and community settings where these are developed (Coloroso, 2004; Kochenderfer-Ladd, Ladd, & Kochel, 2009; Postigo, González, Montoya, & Ordóñez, 2013).

Within this complexity, one line that has proved fruitful in the study of bullying is that relating to the management of emotions in aggressors and victims, in respect of which they have addressed issues such as empathy (Eisenberg, Eggum, & Di Giunta, 2010; Jolliffe & Farrington, 2007), moral regulation (Perren, Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, Malti, & Hymel, 2012; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007), emotional self-control (Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004) and management of shame and guilt for offenses committed against others (Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2004; Gilligan, 1996).

It is precisely the management of shame in situations of bullying, the aspect related to the topic of interest in this study. The research is part of the line of work that studies the individual's consciousness about emotions related to compliance or otherwise of social norms that are accepted in a given context (Lemerise & Arsenio, 2000; Lewis, 1992; Menesini & Camodeca, 2008; Morrison, 2006).

Shame is an emotion that has proven to have an important role in the regulation of moral conduct, particularly in the relationship and responsibility toward others (Scheff, 1995; Tangney et al., 2007; Totfi & Farrington, 2008).

When the experience of shame is associated by the individual with the recognition that their conduct violates ethical values that are part of their moral identity, feelings of guilt are experienced which favor serious efforts not to repeat such behavior and action is taken to repair the damage (Arsenio, 2014; Braithwaite & Braithwaite, 2001; Harris, 2001; Menesini & Camodeca, 2008; Tagney, 1995).

Individuals can either displace or acknowledge the shame that arises when others witness their conducts violating their own ethical identity (Braithwaite, 1989; Pontzer, 2009). Displacement of shame means avoiding negative experiences associated with this emotion by attributing blame to others. This is socially maladaptive because it increases the likelihood of negative behavior to be repeated (Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2004; Scheff & Retzinger, 2002).

On the other side, acknowledgment of shame presupposes acceptance that the conduct is wrong and socially undesirable. Such strategy is socially effective as it helps to maintain healthy interpersonal relationships associated with a desire to repair the error and decreases the likelihood that the individual will again engage in similar situations (Haro et al., 2013; Menesini et al., 2003; Ttofi & Farrington, 2008). Acknowledgment, forgiveness and reconciliation, together, play an important role in the implementation of restorative justice, which has shown its value in preventing bullying (Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2006; Morrison, 2006).

This illustrates the importance of studying the ways of managing shame in situations of aggression among peers, in order to broaden the understanding of the bullying phenomenon and thus being in a better condition to develop strategies that promote coexistence in schools. To work effectively with this construct, instruments providing valid and reliable information are needed. Despite the undeniable value that the study of shame management has on the theme of bullying and the need for quality information about this construct, no published studies were found in Latin America, particularly in Mexico, regarding the analysis of psychometric properties of an instrument for measuring the management of shame among adolescent students. To address this deficiency, the present study aimed to determine the validity and reliability of an adaptation, for Mexican adolescents, of the questionnaire developed by Ahmed (1999) to measure the "State of shame - Shame Acknowledgment and Shame Displacement" (MOSS-SAST).

The study hypothesized that adaptation of the instrument has reliability and validity evidence strong enough to be considered as an empirically supported model for measuring shame management in Mexican adolescents.

METHOD

Participants

700 students from eight public high schools in a municipality of the state of Sonora, located in Northwestern Mexico, were selected by non-probability sampling during the months of January to May 2014. Of these, 45.5% were male and 54.5% female; also, 34.8% were enrolled in first grade, 37.9% in second grade and 27.3% in third grade.

The total sample was randomly divided into two subsamples of 350 each, in order to perform the exploratory factor analysis and then a confirmatory test with various samples of students.

Instrument

The questionnaire prepared by Ahmed (1999) was used to measure the "State of shame - Shame Acknowledgment and Shame Displacement". This instrument consists of eight scenes with 10 possible response options of which five indicate acknowledgment of shame (e.g. You feel ashamed of yourself) and the other five, displacement of shame (e.g. You feel annoyed with others for what happened).

The instructions asked the students to imagine they were in the scenes described and then requested them to express the feelings generated by them. This instrument was answered with a dichotomous scale Yes or No, by which the presence or absence of an identified feeling was indicated.To carry out the adaptation of the instrument, the purpose was to find people with extensive English language proficiency and experience in the field of Psychology to perform the translation. Subsequently, the instrument with the relevant instructions was sent to 10 experts on the subject. The judges were asked to assess the scenes according to the following characteristics: (a) represent the population under study, (b) show different types of abuse, (c) be familiar to the participants of the study and (d) be possible provocateurs of shame (Ahmed, 1999).

As a result of the content validity in the amended version, three scenes proposed by the author were removed due to the consistency in the responses of the experts regarding that they were unrepresentative of the sample of students with whom the study would be conducted. An example of the deleted scenes is the following: Imagine you're in school and you see a younger student, you take the sweet off his hands and the teacher sees what you did.

In the end, the scale was made up of six scenes. Based on content analysis, another scene was added to the other five that remained in the original version. This was decided to represent a situation of cyberbullying, aspect that is not covered in the original instrument but that the experts suggested, given the frequency with which this type of aggression is reported in Mexican students (Del Río, Bringue, Sádaba, & González, 2009; Lucio, 2009; Valdés, Carlos, Tanori, & Wendlandt, 2014; Vega, González, & Quintero, 2013; Velázquez, 2009).

With regard to the response options for each scene, the original ten given by the author were preserved. However, the original dichotomous scale was replaced by another one, Likert type, with five response options ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always) to generate greater representativeness and variability in students' responses. It's worthy to highlight that this latter type of scale was used in an adaptation of the instrument made in Bangladesh by Ahmed and Braithwaite (2006).

Procedure

The aim of the study was explained to the school authorities and they were asked permission to have access to these schools. Once this permission was granted, informed written consent of the students' parents was requested. Finally, the voluntary participation of students was sought guaranteeing the confidentiality of the information they provided.

To analyze the psychometric properties of the instrument, evidence of the following processes was established: (a) content validity by experts' judgment, (b) construct validity through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis with different samples, (c) criterion validity through its ability to distinguish between groups of students with and without bullying reports, and (d) reliability, determined by the scores' internal consistency. Statistical analysis of data was performed with support of SPSS. AMOS 22.

RESULTS

Evidence of the psychometric properties of the scale scores is presented including reliability (Cronbach's Alpha), construct validity (exploratory and confirmatory factor) and criterion validity (comparison of scale scores of students with and without reports of bullying).

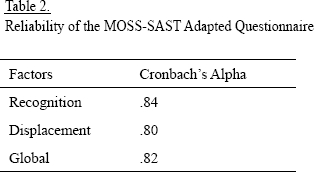

Reliability

Through Cronbach's Alpha, correlation of items with scale scores was determined (see table 1). The items correlation was higher than .30, so it was decided to include them in the analysis (De Vellis, 2012).

The scale's reliability evidence was established by analyzing its internal consistency through Cronbach's Alpha, which showed that in general, as well as in the subscales, the instrument has an acceptable reliability (see table 2)

Construct validity

Exploratory factor analysis. An exploratory factor analysis was performed with the Oblimin rotation method (delta equal to zero) and extraction of maximum likelihood. Data showed a good fit for this type of model which was evident in the significance of Bartlett's sphericity test (c2 = 7323.5, p < .001) and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin's value (KMO) of .81 (Cea, 2004; Martínez, Hernández, & Hernández, 2006).

As inclusion criteria for these items, it was considered they ought to have a load factor of .30 or higher and that these values would only be observed in one of the factors, which indicates the theoretical strength of the item (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1999; Martínez et al., 2006). The item: Would you be unable to decide if you were guilty?was removed since it presented high factor loadings on two factors which is an indication of poor conceptual clarity or comprehension difficulties (Cea, 2004).

The remaining nine items were grouped into two factors and together explained 80.8% of the variance of the instrument's scores. The first factor, composed of five items, explained 50.6%, and the second, consisting of four items, amounted to explain 30.2% of the scores' variance (see table 3).

Confirmatory factor analysis. From the results of exploratory factor analysis, a measurement model for the construct "handling of shame" was proposed in which the presence of two factors negatively correlated was established (see figure 1).

The method of Maximum Likelihood estimation was used to determine the goodness of fit of the empirical model. It obtained a satisfactory overall fit because the c2 had a value of 5.16 with an associated p-value of 3.271 so it can be said that there are no statistically significant differences between the observed variance-covariance matrices versus the ones predicted by the model. Moreover, the various adjustment indices analyzed were all suitable (CMIN = 1.29; GFI = .98; CFI = .99; NFI= .97; RMSEA = .05) which implies that the proposed model is empirically sustainable (Blunch, 2013; Cea, 2004; Figure 2).

Criterion validity

In order to show this type of validity evidence it was verified whether the instrument differentiated between students with and without reports of bullying. The tool developed by Valdés and Carlos (2014) was used to measure bullying reports. It consists of nine items assessing the various types of violence (physical, psychological and social). These were answered using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never), 2 (Almost Never) (once or twice a month), 3 (Sometimes) (three to four times a month), 4 (Almost always) (five to seven times a month) and 5 (Always) (more than seven times a month). The authors reported measure reliability with Cronbach's Alpha of .87.

To identify subgroups of students with and without reports of bullying, the criterion proposed by Solberg and Olweus (2003) was used. According to it, the presence of three or more reports of violence acts toward peers during the last month led to consider a student as aggressor. Based on this criterion, 69 (9.8%) students with reports of bullying were identified. From the group that reported no bullying, a subsample of the same size as the one of the aggressors group was taken randomly, to strengthen the results of comparisons between the two subgroups.

A t-test for independent samples was used to compare the scores resulting from the factors Acknowledgment and Displacement of shame between the two subgroups. It was found that there were significant differences in the scores of students groups with and without reports of bullying in the two factors assessed. The analysis revealed that the average scores were significantly lower in recognition and higher in the group that reported bullying. The analysis of the extent of the effect size leads to the conclusion that the difference detected between the two subgroups of students in the two factors assessed is of medium magnitude (Cárdenas & Arancibia, 2014; table 4).

DISCUSSION

It is concluded that adaptation of the MOSS-SAST questionnaire (1999) to measure management of shame in Mexican adolescents is empirically sustainable. Obtaining, by confirmatory factor analysis, a measurement model of the construct consisting of two factors (Acknowledgment and Displacement) negatively correlated, coincides with what other studies have reported about the instrument (Ahmed, 1999; Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2006) and supports the existence of an invariant factorial structure of the questionnaire.

The findings reaffirm the theory that, in embarrassing situations, individuals can either recognize this emotion which means accepting the error and attempting to repair it or possibly displace the shame, blaming others for the situation and/or getting angry to themselves for having been found when engaging in it (Ahmed, 1999; Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2004; Åslund, Starrin, Leppert, & Nilsson, 2009). Acknowledgment of shame means that students perceive their aggressive behavior towards peers as a negative act for their moral identity, which also generates feelings of guilt, thereby decreasing the likelihood that this aggressive behavior will be repeated (Arsenio, 2014; Braithwaite & Braithwaite, 2001; Harris, 2001).

Moreover, the usefulness of the instrument was confirmed since, according to the findings of other studies (Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2006; Menesini & Camodeca, 2008; Olthof, 2012; Pontzer, 2009), the scale managed to differentiate between groups of students with and without bullying reports. This proved its value as a tool in the investigation of both, management of shame and identification of aggressors or students at risk for this type of behavior. Nevertheless, undoubtedly, more studies are necessary on this matter. Shame acknowledgment means that children perceive their aggressive behavior in terms of moral responsibility, which is expressed in feelings of shame and guilt that are in turn powerful regulators of their moral behavior (Menesini, Palladino, & Nocentini, 2015). However, displacement is associated with moral disengagement, which disables moral control and justifies negative behavior (Bandura, 2002).

Having validated instruments to measure the management of shame facilitates the advancement of research related to the role of emotions in moral development, particularly in the understanding of peer violence, which proves to be a fruitful comprehensive framework for this problem (Eisenberg, 2000; Hinnant, Nelson, O'Brien Keane, & Calkins, 2013).

An additional contribution of the study is having obtained a scale that, in addition to its robust psychometric properties and being able to explain a very high portion of the construct's variance (80.8%), was less extensive than the original version (Ahmed, 1999). This makes it a more parsimonious version which in turn means, among other things, reduced workload for researchers and participants who respond the instrument. All of this enables a faster administration and an easier interpretation.

It is concluded that this version of the MOSS-SAST questionnaire is an instrument that can be used in the investigation of the construct in question in Mexican adolescents. However, a limitation of the study is that it focused on middle-class teenagers, so it is necessary to investigate the factorial invariance of the scale in other cultural contexts and adolescents who are out of school, in order to extend its potential for use in different contexts and cultural conditions.

REFERENCES

1. Ahmed, E. (1999). Shame management and bullying (Tesis Doctoral, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia). Recuperada de https://digitalcollections.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/10624/1/01Front_Ahmed.pdf [ Links ]

2. Ahmed, E., & Braithwaite, V. (2004). "What, Me Ashamed?" Shame management and school bullying. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 41, 269-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022427804266547 [ Links ]

3. Ahmed, E., & Braithwaite, V. (2006). Forgiveness, reconciliation, and shame: Three key variables in reducing school bullying. Journal of Social Issues, 62, 347-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2006.00454.x [ Links ]

4. Allen, K. (2010). Classroom management, bullying, and teacher practices. The Professional Educator, 34(1), 1-16. [ Links ]

5. Arsenio, W. (2014). Moral emotion attributions and aggression. En M. Killen & J. Smetana (Eds.), Handbook of moral development (2da ed., pp. 235-255). New York, USA: Psychological Press. [ Links ]

6. Aslund, C., Starrin, B., Leppert, J., & Nilsson, K. (2009). Social status and shaming experiences related to adolescent overt aggression at school. Aggressive Behavior, 35, 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ab.20286 [ Links ]

7. Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31, 101-119. http://dx.doi.org.10.1080/0305724022014322 [ Links ]

8. Blaya, C., Debarbieux, E., Del Rey, R., & Ortega, R. (2006). Clima y violencia escolar. Un estudio comparativo entre España y Francia. Revista de Educación, 339, 293-315. [ Links ]

9. Blunch, N. (2013). Introduction to structural equation modeling using IBM SPSS Statistics and Amos(2nd ed.). Londres: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

10. Braithwaite, J. (1989). Crime, shame and reintegration. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

11. Braithwaite, J., & Braithwaite, V. (2001). Shame, shame management and regulation. Shame management through reintegration. En E. Ahmed, N. Harris, J. Braithwaite & V. Braithwaite (Eds.), Shame management through reintegration (pp. 3-69). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

12. Cárdenas, M., & Arancibia, H. (2014). Potencia estadística y cálculo del tamaño del efecto en G Power: Complementos a las pruebas de significación estadística y su aplicación en psicología. Salud y Sociedad, 5(2), 210-224. [ Links ]

13. Castillo, C., & Pacheco, M. (2008). Perfil del maltrato (bullying) entre estudiantes de secundaria en la ciudad de Mérida, Yucatán. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 13(38), 825-842. [ Links ]

14. Cea, M. (2004). Análisis multivariable. Teoría y práctica en la investigación social. Madrid: Síntesis. [ Links ]

15. Collie, R., Shapka, J., & Perry, N. (2011). Predicting teacher commitment: The impact of school climate and social-emotional learning. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 1034-1048. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pits.20611 [ Links ]

16. Coloroso, B. (2004). The bully, the bullied, and the bystander: From preschool to high school-how parents and teachers can help break the cycle of violence. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. [ Links ]

17. De Vellis, R. (2012). Scale development. Theory and applications (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE. [ Links ]

18. Del Río, J., Bringue, X., Sádaba, C., & González, D. (2009). Cyberbullying: Un análisis comparativo en estudiantes de Argentina, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, México, Perú y Venezuela. Ponencia en extenso, V Congrés Internacional Comunicació I Realitat, Universidad de Navarra, España. Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/10171/17800 [ Links ]

19. Einsenberg, N. (2000). Emotions, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 665-697. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1665 [ Links ]

20. Eisenberg, N., Eggum, N., & Di Giunta, L. (2010). Empathyrelated responding: Associations with prosocial behavior, aggression, and intergroup relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 4, 143-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2010.01020.x [ Links ]

21. Eljach, S. (2011). Violencia escolar en América Latina y el Caribe: Superficie y fondo. Panamá: Plan International/UNICEF. [ Links ]

22. Gilligan, J. (1996). Exploring shame in special settings: A psychotherapeutic study. En C. Cordess & M. Cox (Eds.), Forensic psychotherapy: Crime, psychodynamics & the offender patient (pp. 475-489). London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [ Links ]

23. Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1999). Análisis Multivariante (5ta ed.). Madrid: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

24. Haro, I., García, B., & Reidl, L. (2013). Experiencias de culpa y vergüenza en situaciones de maltrato entre iguales en alumnos de secundaria. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 18(59), 1047-1075. [ Links ]

25. Harris, N. (2001). Shaming and shame: Regulating drinkdriving. En E. Ahmed, N. Harris, J. Braithwaite & V. Braithwaite (Eds.), Shame management through reintegration (pp. 73-210). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

26. Hinnant, J., Nelson, J., O'Brien, M., Keane, S., & Calkins, S. (2013). The interactive roles of parenting, emotion regulation and executive functioning in moral reasoning during middle childhood. Cognition and Emotions, 25, 1460-1468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.789792 [ Links ]

27. Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación (2007). Disciplina, violencia y consumo de sustancias nocivas a la salud en escuelas primarias y secundarias de México. México: INEE. [ Links ]

28. Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. (2007). Examining the relationship between low empathy and self-reported offending. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 12, 265-286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/135532506x147413 [ Links ]

29. Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., Ladd, G., & Kochel, K. (2009). A child and environment framework for studying risk for peer victimization. En M. Harris (Ed.), Bullying, rejection, & peer victimization: A social cognitive neuroscience perspective (pp. 27-52). New York, N.Y.: Springer Publishing Company. [ Links ]

30. Lemerise, E., & Arsenio, W. (2000). An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Development, 71, 107-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00124 [ Links ]

31. Lewis, M. (1992). Shame: The exposed self. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

32. Lucio, L. (2009). El cyberbullying en estudiantes del nivel medio superior en México, Ponencia en extenso X Congreso Nacional de Investigación Educativa, Veracruz, México, COMIE. [ Links ]

33. Martínez, M., Hernández, M., & Hernández, M. (2009). Psicometría. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

34. Menesini, E., & Camodeca, M. (2008). Shame and guilt as behaviour regulators: Relationships with bullying, victimization and prosocial behaviour. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 26, 183-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/0261510 07x205281 [ Links ]

35. Menesini, E., Palladino, B., & Nocentini, A. (2015). Emotions of moral disengagement, class norms and bullying in adolescence: A multinivel approach. Merril-Palmer Quaterly, 61(1), 124-143. [ Links ]

36. Morrison, B. (2006). School bullying and restorative justice: Toward a theoretical understanding of the role of respect, pride, and shame. Journal of Social Issues, 62, 371-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2006.00455.x [ Links ]

37. Olthof, T. (2012). Anticipated feelings of guilt and shame as predictors of early adolescents' antisocial and prosocial interpersonal behaviour. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9, 371-388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.680300 [ Links ]

38. Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school. What we know and what we can do. UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

39. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación la Ciencia y la Cultura /Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Evaluación de la Calidad de la Educación (2012). Análisis del clima escolar ¿Poderoso factor que explica el aprendizaje en América Latina y el Caribe? Santiago de Chile: Oficina Regional de Educación para América Latina y el Caribe (OREALC/UNESCO. [ Links ]

40. Ortega, R. (2010). Treinta años de investigación y prevención del "bullying" y la violencia escolar. En R. Ortega (Ed.), Agresividad injustificada, bullying y violencia escolar (pp. 15-32). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

41. Ortega, R., Sánchez, V., Ortega, J., Del Rey, R., & Genebat, R. (2005). Violencia escolar en Nicaragua. Un estudio descriptivo en escuelas primarias. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 10(26), 787-804. [ Links ]

42. Perren, S., Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., Malti, T., & Hymel, S. (2012). Moral reasoning and emotion attributions of adolescent bullies, victims, and bully-victims. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 30, 511-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02059.x [ Links ]

43. Pontzer, D. (2009). A theoretical test of bullying behavior: Parenting, personality, and the bully/victim relationship. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 259-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-009-9289-5 [ Links ]

44. Postigo, S., González, R., Montoya, I., & Ordóñez, A. (2013). Propuestas teóricas en la investigación sobre acoso escolar: Una revisión. Anales de Psicología, 29, 413-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.2.148251 [ Links ]

45. Raviv, A., Erel, O., Fox, N., Leavitt, L., Raviv, A., Dar, I., Shahinfar, A., & Greenbaum, C. (2001). Individual measurement of exposure to everyday violence among schoolchildren across various settings. Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 117-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(200103)29:2<117::AID-JCOP1009>3.0.CO;2-2 [ Links ]

46. Robers, S., Zhang, J., Truman, J., & Snyder, T. (2012). Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2011 [NCES 2012-002/ NCJ 236021]. Washington, D.C: National Center for Education Statistics/U.S. Department of Education/Bureau of Justice Statistics. [ Links ]

47. Román, M., & Murillo, J. (2011). América Latina: Violencia entre estudiantes y desempeño escolar. Revista CEPAL, 104, 37-54. [ Links ]

48. Scheff, T. (1995). Editor's introduction: Shame and related emotions: An overview. American Behavioral Scientist, 38, 1053-1059. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002764295038008002 [ Links ]

49. Scheff, T., & Retzinger, S. (2002). Emotions and Violence: Shame and Rage in Destructive Conflicts. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books/D. C. Heath. [ Links ]

50. Solberg, M., & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 239-268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ab.10047 [ Links ]

51. Swearer, S., Espelage, D., & Napolitano, S. (2009). Bullying Prevention and Intervention: Realistic Strategies for Schools. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

52. Tangney, J. (1995). Recent advances in the empirical study of shame and guilt. American Behavioral Scientist, 38, 1132- 1145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002764295038008008 [ Links ]

53. Tangney, J., Baumeister, R., & Boone, A. (2004). High selfcontrol predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72, 271-324. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x [ Links ]

54. Tangney, J., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145 [ Links ]

55. Ttofi, M., & Farrington, D. (2008). Reintegrative shaming theory, moral emotions and bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 34, 352-368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ab.20257 [ Links ]

56. Valdés, A., & Carlos, E. (2014). Relación entre el autoconcepto social, el clima familiar y el clima escolar con el bullying en estudiantes de secundarias. Avances de Psicología Latinoamericana, 32, 447-457. http://dx.doi.org/10.12804/apl32.03.2014.07 [ Links ]

57. Valdés, A., Carlos, E., Tanori, J., & Wendlandt, T. (2014). Differences in types and technological means by which Mexican high school students perform cyberbullying: Its relationship with traditional bullying. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 4, 105-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jedp.v4n1p105 [ Links ]

58. Valdés, A., Carlos, E., & Torres, G. (2012). Diferencias en la situación socioeconómica, clima y ajuste familiar de estudiantes con reportes de bullying y sin ellos. Psicología desde el Caribe, 29(3), 616-631. [ Links ]

59. Vázquez, R., Villanueva, A., Rizo, A., & Ramos, M. (2005). La comunidad de la preparatoria 2 de la universidad de Guadalajara. Actitudes de sus miembros con respecto a la violencia y no violencia escolar. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 10(27), 1047-1070. [ Links ]

60. Vega, M., González, G., & Quintero, P. (2013). Ciberacoso: Victimización de alumnos en escuelas secundarias públicas de Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, México. Revista Educación y Desarrollo, 25(2), 13-20. [ Links ]

61. Velázquez, L. (2009). Cyberbullying. El crudo problema de la victimización en línea, Ponencia en extenso, X Congreso Nacional de Investigación Educativa, Veracruz, México, COMIE. [ Links ]

text in

text in