INTRODUCTION

Cancer affects millions of people around the world, and there are currently around 25 million diagnosed patients. Cancer is estimated to be responsible for 13% of deaths worldwide in 2008 (Barbaric et al., 2010) and has a high financial cost (Araújo et al., 2009). It is estimated that by the year 2030 this disease will account for 13.1 million deaths annually (World Health Organization, 2013).

The rate of survival has increased, in part, due to tech nological and medical advances (Siegel et al., 2012). The mortality rate declined by 19.2% in males and by 11.4% in females between 1990 and 2005. This decline resulted in part from the lower rate of development of the main cancers affecting each sex, namely lung, breast, prostate and colorectal cancer (Jemal, et al., 2009). According to the American Cancer Society (2016), in the USA there were 14.5 million cancer survivors as of 2016, and an estimated 1,685,210 new cases were diagnosed, while an estimated 595,690 died that same year. Thanks to behavioral changes and greater adherence to healthy lifestyles, there was a 23% decrease in mortality between 1991 and 2012, which in practice translates to 1.7 million people who survive.

In Europe, there were an estimated 3.45 million new cancers (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) and 1.75 million deaths in 2012. When we look at these figures by type of cancer we find that the most frequent were cancer of the breast (464,000 cases) followed by colorectal (447,000), prostate (417,000) and lung (410,000) cancer. These four types of cancer account for half of the global burden of cancer in Europe. The most common causes of death by cancer type are lung (353,000), colorectal (215,000) breast (131,000), and stomach (107,000) cancer. The number of new cancer cases across Europe was 1.4 million in men and 1.2 million in women and around 707,000 men and 555,000 women died of cancer in the same year of diagnosis.

Cancer is one of the diseases that causes the most changes in individuals. The changes are at the physical and psychological level, as well as at the social level, and on the whole, it compromises the full functioning of the individual (Elsner, Trentin, & Horn, 2009; Marcon, Radovanovic, Waidman, Oliveira, & Sales, 2015). One of the dimensions affected is sexuality (Gianini, 2004; Serrano, 2005; Valério, 2007). In addition to the physical sexual act itself, all the factors that allow us to experience sexuality in its fullness are impacted (Santos, 2011). In addition to the effects directly associated with the disease, there are also those that come as a side effect of the therapeutic interven tions used. One of the most prevalent negative effects in these patients is fatigue (Battaglini, et al., 2006; Diettrich, Miranda, Honer, Furtado, & Correa-Filho, 2006; Ishikawa, Derchain, & Thuler, 2005; McAuley, White, Rogers, Motl , & Courneya, 2010; Siegel, et al., 2012). Studies show that fatigue increases during radiotherapy and chemotherapy treatment periods (Diethich et al., 2006; Ishikawa et al., 2005), with about 90% of cases reporting fatigue, often over an extended period involving suffering of many other sorts as well. Fatigue and negative body image is reported even after the end of the treatments, and both have a direct impact on the person's sexual desire (Siegel, et al., 2012) among 17% to 26% of cancer survivors (Diettrich, et al., 2006; Siegel, et al., 2012).

Sexuality is one of the areas strongly affected by cancer treatments. In men, about 80% of survivors, especially prostate cancer patients who undergo prostatectomy, radia tion therapy or hormone therapy, have sexual dysfunction. Among men, the most prevalent complaint is that of erectile dysfunction, and in women diagnosed with breast cancer, and gynecology are those that cause more complaints at this level (Siegel et al., 2012).

In females, pain during intercourse, decreased libido, and vaginal dryness are the most common side effects (Melisko, Goldman, & Rugo, 2010). In the case of men, the most common side effect is difficulties of erection, especially among those who receive treatment in the pelvic area such as in the prostate, bladder, among others (Gianini, 2004). In cases with phenotype changes including loss of body parts usually associated with sexuality, as happens in the case of breast cancer (i.e. mastectomy) and prostate cancer, patients tend to have feelings of loss of sexual identity and sexual attractiveness, and these are some of the reasons for loss of motivation for sexual intercourse (Flynn, et al., 2011; Hill, et al., 2011).

Decreased sexual appetite after treatment is common in both sexes (Gianini, 2004). In addition, it is important to note that there is a lack of evidence for the effects of this type of chemotherapy. The fact that hormonal changes and sometimes physical changes contribute to a decrease in sexual desire and therefore the frequency of sexual activity also decreases (Valdivieso, Kujawa, Jones, & Baker, 2012).

Patients with cancer in gynecological areas and indi viduals with prostate cancer suffer damage in anatomical regions that are associated with a greater possibility of sexual dysfunction and infertility. This fact should be taken into account by health professionals, since it is possible to minimize the consequences of infertility through the pre servation of ova, the preservation of ovarian tissue and a lower level of chemotherapy in this region where possible. In the case of males it is recommended to perform semen collection, so that in the future these patients can ensure their reproduction (Valdivieso, et al., 2012). Empirical evidence suggests that this whole situation directly interferes with the subjects' sexuality, both physically and emotionally. Failing to maintain intercourse, having erectile dysfunction, as well as pain in intercourse, and decreased libido are just a few examples of the consequences that cancer has for individuals.

Even when the effects are not visible in physical terms, emotional distress may impede the sexual functioning of patients both during treatment and in the posttreatment period (Flynn, et al., 2011). In the initial phase of diagno sis, as well as before initiating treatments, patients reveal that they feel changes in their body image and sexual dispositions, which cause negative changes in their rela tionships (Sacerdoti, Lagana, & Koopman, 2010). In part, social and family relationships are affected by depressed mood, menopausal symptoms, and body image problems, making them important predictors of the decline in sexual activity (Peréz et al., 2010). Among the body alterations that contribute most to lower predisposition rates for acts of greater physical intimacy and even sexual desire are hair loss, weight gain, and scars (Barbosa, 2008; Flynn, et al., 2011 ). Treatments include several alterations that, in addition to affecting the body, have as a consequence the reduction of self-esteem (Flynn et al., 2011, Ramirez et al., 2009; Sacerdoti, et al. Al., 2010). Women with breast cancer who underwent mastectomy surgery show greater sexual interest and greater sexual activity compared to mastectomized women who show lower feelings of sexual attraction (Peréz, et al., 2010).

Scientific research has been able to identify a set of parameters that affect the sexuality of oncological patients (Hill, et al., 2011), but this knowledge is of a general nature. However, this same research has neglected how feelings about sexuality vary among each of the situations (read diagnoses) that the patients are facing and that allows health professionals to have more appropriate interventions due to the type and stage of cancer of the patients with whom they work. Individuals aged between 50 and 64 years are those who report the most problems in terms of sexuality (Harden, et al., 2008; Lindau, Surawska, Paice, & Baron, 2011).

All of these successive changes lead to emotional dis tress for these patients and should be taken into account by health professionals working directly with these patients (Fortune-Greeley et al., 2009, Hill et al., 2011; 2011).

Although at an early stage, the issue of sexuality is not a priority, since everything focuses on avoiding higher damage and death itself, later this dimension affects the quality of life of patients, since sexual dysfunction is associated, in both sexes, with feelings of anguish, as well as depressive symptoms and anxiety (Flynn, et al., 2011, Lindau, et al., 2011; Zebrack, Foley, Wittmann, & Leonard, 2010).

Among breast cancer survivors, it is noted that during the first few years they have more difficulties in terms of attraction, interest and sexual pleasure, and consequently a decrease in satisfaction with their sexual life (Peréz, et al., 2010). Feelings of loss of sexual identity and sexual attractiveness are some of the elements that lead to the loss of one's own motivation for sexual intercourse (Flynn, et al., 2011; Hill, et al., 2011). For effective planning and intervention, health professionals lack training (Cesnik, et al., 2013) and normative information.

The main purpose of the present study is to compare individuals diagnosed with cancer with those non-diagnosed in terms of satisfaction with the sexual relationship (self-esteem, sexual functioning, and general relationship). The specific goals are: compare by type of cancer, time since diagnosis (How long have you been diagnosed with can cer?), type of treatment and changes in body image, which includes bodily alteration, loss of limb (may be visible or not), weight gain, fatigue, sexual problems (Including the subjective problems that each participant considered), hair loss, weight loss and vomiting, at the level of the dimen sions of sexuality.

METHOD

This study applied a transversal and descriptive design.

Participants

The sample consisted of 95 people with cancer and 89 without cancer, making a total of 184 participants aged between 19 and 84 years. In the group diagnosed with cancer, the age ranged from 26 to 84 years and in the group without cancer between 19 and 67 years of age. Of the total sample, 62 are males and 122 females. One hundred of the participants live in rural areas, and the remaining live in the urban environment. The majority of the sample, 51.1%, are married. Among the remainder, 39.7% are single, 4.3% are widows and 4.9% are divorced.

The sample was organized into two groups, those with a diagnosis of cancer and those who did not have such diagnosis. The groups created by type of cancer were: breast (35), cancer of the digestive tract (9), which included cancer of the intestine and stomach, cancer of the urological system (34), cancer of the kidneys, bladder, and prostate and a class called others (17). This class was created to include participants who were not included in any other class because they did not have a sufficient number to do so. This class includes participants with head and neck can cer, gynecological, bone, lymphoma, melanoma, sarcoma, myelanoma and rectal colon.

Depending on the characteristics of the sample, inde pendent variables were defined as having cancer or not, type of cancer, time of diagnosis, type of treatment and changes in body image/phenotype, limb loss, weight gain, weight loss, fatigue, previous sexual problems, hair loss and the occurrence of vomiting. The dependent variables result from the scales of the instrument used, namely: se xual functioning, self-esteem, and relationships in general.

The data were collected in different ways. One of the techniques was sampling by convenience and for the cli nical sample, the snowball method was used. This method consists in indicating participants to the sample, by other participants (Freitas, Oliveira, Saccol, & Moscarola, 2000). This method resulted in the collection of 41 questionnaires, but four were considered invalid.

Instruments

The instruments used included a sociodemographic data questionnaire in the initial part of the instrument, which gathered information about age, sex, place of residence, marital status, type of cancer and treatment received. These questions were followed by the the Portuguese version (Pais-Ribeiro & Raimundo, 2005) of the Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire (QSRS) (Cappelleri, et al., 2004). The QSRS consists of 14 items in the original version and 13 in the Portuguese version. In the present study, we used the 14 item version since the item that was withdrawn in the Portuguese adaptation resulted from the fact that the sample was exclusively female and the item was directed to the male population.

The items are subdivided into two dimensions, "Satisfaction with Sexual Functioning" and "Confidence," which in turn is subdivided into two: "Self-esteem" and "Relationship in General" (Pais-Ribeiro, Raimundo, & Ribeiro, 2007).

The Portuguese version shows values of good internal consistency and Cronbach's alpha values between .7 and .92. The value for the total scale was .90. The correlations of the items with the total score of the scale to which they belong, corrected for overlap, for the seven items of the sexual functioning dimension ranged from .53 to .87 with the majority of the values in the .80 range: self-esteem .50 and .81, 4 tens; General relationship is .59, 2 items; Confidence (self-esteem + general relationship), .50 and .75, with most values in the .70 range. Showing good convergent-discriminant validity (Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2005).

Procedure

After obtaining the authorizations and approval from the ethics committee, the questionnaires were collected at the hospital, individually. This second method resulted in the collection of 54 questionnaires. For the constitution of the non-cancer group, questionnaires were distributed to people with no history of oncological disease at university hospital faculty and in public places.

At the beginning of the questionnaire application, participants were explained that they were providing data for a scientific study and that all data were confidential, anonymous and would be used only in the context of the research. Before they proceeded to fill out the questionnaire they signed the terms of free consent. It was asked if there were doubts that could be clarified and asked that the an swers given be as honestly as possible and that all items be filled out. In some cases at the request of the participants, it was necessary for the researcher to record the answers given. Finally, we thanked all of them for their cooperation.

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro and the Hospital Center of the North Region where the question naires were collected.

Statistical procedures

Initially, a descriptive analysis of the independent variables was performed, where the means and respective standard deviations were analyzed, as well as the distri bution of the sample by sex, place of residence, marital status, cancer history and diagnosis time. Cronbach's alpha was used to obtain the internal consistency values of each of the sub-scales used. Finally, we performed Univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA). For the analysis of the data we adopted the significance level of p <.05 and the T|p 2 > .01 as weak, > .04 as moderate and > .40 as strong. The value of T|p 2 was taken into account in order to obtain conclusions not only for the study population but to be able to draw a conclusion for the population in general.

The normality of the data was confirmed by the M-BOX Test, as well as the Levene Test. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 was used to analyze the data.

RESULTS

It should be noted that 42 participants were on treatment (22.8%) and 53 (28.8%) had already finished treatment. Thirteen percent of the sample was diagnosed less than one year ago, 15.2% knew they had the disease for less than 3 years, 8.2% were diagnosed for less than 5 years, and the remaining 15.2% were diagnosed for more than five years.

When we compared individuals by history of cancer (Table 1), MANOVA showed a multivariate effect of the non-cancer group and the cancer group for the dependent variable satisfaction with sexual intercourse (F (3,168) = 3.393; p = .019; Wilks λ = .943), with a moderate effect (ηp 2 = .057).

Table 1 Comparison of the cancer group and the non-cancer group at the level of satisfaction of sexual relationship.

| With a history of cancer M ± DP | No history of cancer M ± DP | F | p | P.O. | ||

| Self esteem | 15.68 ± 3.17 | 15.48 ± 1.88 | 1.029 | .312 | .006 | .172 |

| Satisfaction with Sexual Functioning | 17.93 ± 9.67 | 30.19 ± 4.21 | 9.419 | .003 | .052 | .863 |

| Relationship in General | 8.41 ± 2.03 | 8.83 ± 1.35 | .501 | .480 | .003 | .108 |

Univariate analysis showed a moderate effect on the variable sexual functioning. MANOVA shows that indi viduals with a history of oncological disease have lower values (17.93 ± 9.67) for sexual functioning, compared to individuals with no history of oncological disease (30.19 ± 4.21). On the other dimensions, no statistically significant differences were found.

When comparing different types of cancer at the level of sexual satisfaction (table 2), a multivariate effect among different types of cancer was found for the dependent va riable satisfaction with sexual intercourse (F (9,214) = 5,087; p = .001; Wilks λ = .655), with a strong effect (ηp 2= .145).

Table 2 Comparison of different types of cancer inn the level of sexual satisfaction Self esteem Satisfaction with Sexual Functioning Relationship in General.

| Breast cancer M ± DP | Urological cancer M ± DP | Digestive cancer M ± DP | Other types of cancer M ± DP | F | p | r p 2 | P.O. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.83 ± 3.34 | 16.76 ± 2.85 | 13.63 ± 5.68 | 14.41 ± 5.05 | 2.72 | .049 | .083 | .643 |

| 19.54 ± 9.36 | 12.29 ± 7.22 | 18.50 ± 12.57 | 23.53 ± 10.12 | 6.82 | .001 | .185 | .972 |

| 8.37 ± 2.25 | 8.24 ± 2.13 | 7.25 ± 3.24 | 8.41 ± 2.32 | .53 | .663 | .017 | .155 |

Univariate analysis demonstrated statistically significant differences in self-esteem, with a moderate effect, and sexual functioning, with a strong effect. Individuals with urological cancer had higher values of self-esteem (16.76 ± 2.85), followed by breast cancer (14.83 ± 3.34) and other types of cancer (14.41 ± 5.05). Digestive cancer was the one with the lowest values (13.63 ± 5.68).

For level of sexual functioning, the group "other types of cancer" presented the highest levels of satisfaction (23.53 ± 10.12). Breast cancer (19.54 ± 9.36) and digestive tract cancer (18.50 ± 12.57) followed, and finally urological cancer had the lowest levels (12.29 ± 7.22).

On the general relation subscale, no statistically signi ficant differences were found.

When we compared the different diagnostic times at the level of sexuality (Table 3), the MANOVA showed a multivariate effect between different diagnostic times in terms of sexual satisfaction (F (12,463) = 11,307; p = .001; Wilks λ =. 507), with a strong effect (ηp 2= .203).

Table 3 Comparison of diagnostic time and level of sexuality.

| Without cancer | < 1 year | 1 to 3 years | 3 to 5 years | > 5 years | |||||

| M±DP | M±DP | M±DP | M±DP | M±DP | F | p | P.O. | ||

| Self esteem | 14.25 ± 4.58 | 14.96 ± 2.96 | 15.64 ± 3.11 | 14.40 ± 5.68 | 15.89 ± 4.15 | 1.147 | .336 | .025 | .356 |

| Satisfaction with Sexual Functioning | 27.78 ± 9.15 | 14.00 ± 9.07 | 22.21 ± 8.25 | 11.93 ± 8.99 | 18.82 ± 10.44 | 18.205 | .001 | .291 | 1.000 |

| Relationship in General | 8.13 ± 2.73 | 8.48 ± 2.17 | 8.50 ± 1.95 | 7.20 ± 3.21 | 8.32 ± 2.31 | .780 | .540 | .017 | .247 |

Univariate analysis demonstrated statistically signifi cant differences in sexual functioning. Individuals with no history of cancer disease had higher levels of satisfaction compared to individuals with a history of cancer disease. Comparisons within the group of individuals with cancer showed that those diagnosed less than one year and 3 to 5 years ago presented less satisfactory values in the sexual functioning dimension. Comparisons at the level of sexual functioning demonstrated differences with a strong statistical effect (.291). The individuals diagnosed in the period bet ween 1 and 3 years ago were those with the highest values and the group diagnosed 3 to 5 years ago was the lowest.

No statistically significant differences were found in self-esteem or for the general relationship items; however, there were weak effects on self-esteem (0.025) and general relationship (0.017).

Comparisons were made for different types of treatment, including radiotherapy, surgery, chemotherapy and a group with "other types of treatment."

When we compared the treatment of radiotherapy to the control group for sexuality we found a multivariate effect between this treatment and the level of sexuality (F (3,180) = 5,653; p = .001; Wilks λ = .914), with a moderate effect (rp 2 =. 086).

Statistically significant results were found for sexual functioning (p = .034) with a weak effect (r^2 = .024), with an observed Power (OP) = .565. Patients who underwent radiation therapy had lower sexual satisfaction ratings (19.00 ± 9.77) than those who did not undergo radiotherapy (23.32 ± 10.84). For this type of treatment, no statistically significant differences with the no radiotherapy group were found in the self-esteem and general relationship variables.

When we compared surgical treatment with no treatment controls for level of sexuality, a multivariate effect was found (F (3180) = 30,403; p = .001; Wilks λ = .664), with a very strong effect (ηp 2 = .336). There were also statistically significant results for self-esteem (p = .015) with a weak effect (ηp 2= .032), with an observed Power (OP) = .681.

Subjects who did not undergo surgical treatment presented lower values for self-esteem (14.18 ± 4.63) compared to individuals who underwent surgical treatment (15.72 ± 3.63).

Statistically significant results were also found in sexual functioning (p = .001) with a strong effect (ηp 2= .155), with an observed Power (OP) = .999. Those who had surgical treatment had significantly lower sexual functioning on ave rage, with values of (17.75 ± 9.74) compared to individuals who did not undergo surgical treatments (26.27 ± 10.05).

For the general relation dimension, no statistically significant effects were found. For the group "other types of treatments", a multivariate effect was also found when we compared the level of sexuality (F (3,180) = 3,152; p = .026; Wilks λ = .950), with a moderate effect (ηp 2= .050). Statistically significant results were found in sexual functioning (p = .008) with a weak effect (ηp 2 = .038), with an observed Power (OP) = .761. Those who had no "other type" of treatment presented higher values of satisfaction in sexual functioning (23.46 ± 10.95) compared to individuals who did not undergo other types of treatments (17.87 ± 8.48).

For level of self-esteem and the general relationship, no statistically significant differences were found. Identical results were obtained when we compared types of treatment on the sexuality scale. However, the results tend to show that individuals who received chemotherapy treatment had less satisfaction at the level of sexual functioning than those who did not.

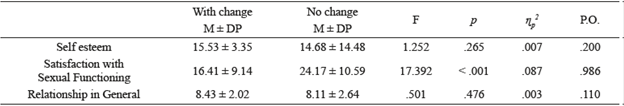

A multivariate effect was found when we compared the phenotype alteration (read body changes) at the level of sexuality (F (3180) = 13,034; p = < .001; (Wilks λ = .822), with a strong effect (ηp 2= .178). Statistically significant results were found for sexual functioning (p = .001) with a moderate effect (ηp 2= .087), with an observed Power (OP) = .986; those who had a phenotype change presented satisfaction values of 16.41 ± 9.14 compared to individuals who did not have phenotype changes due to treatments performed (21.17 ± 10.59). For self-esteem and the general relationship, no statistically significant differences were found (Table 4).

When we compared those who lost a limb with those who had not at the level of sexuality, a multivariate effect was also found (F (3180) = 14,846; p = .001; (Wilks λ = .802), with a strong effect (ηp 2= .198). Statistically significant results were found for sexual functioning (p = .001) with a moderate effect (ηp 2= .111), with an observed Power (OP) = .997, and those who had lost a limb presented lower sexual functioning satisfaction scores (16.68 ± 9.51) than individuals who had no limb loss (24.70 ± 10.41).

We also found a multivariate effect when we analyzed the impact of weight gain on sexuality (F (3,180) = 6,678; p = .001; (Wilks λ = .900), with a moderate effect (rp = .100). Statistically significant results were found in sexual functio ning (p = .005) with a moderate effect (ηp 2= .043), with an observed power (OP) = .813, and those who had a weight gain presented lower values (18.00 ± 9.75) than individuals who did not gain weight (23.62 ± 10.74). For the self-esteem and general relation subscales, no statistically significant results were found.

When we analyzed the relationship between fatigue and satisfaction with sexuality, ANOVA showed a multi-variate effect (F (3180) = 5,764; p = .001; (Wilks λ = .912), with a moderate effect (ηp 2= .088). Statistically significant results were found in sexual functioning (p = .002) with a moderate effect (ƞp2 = .051), with an observed power (OP) = .877, and those who showed fatigue had lower satisfaction values (18.89 ± 9.86) than individuals who did not experience fatigue from the treatments performed (24.15 ± 10.79). For the self-esteem and general relation subscales, no statistically significant data were also found.

We also found a multivariate effect, when we analyzed the relationship between having or not having sexual pro blems and the level of current satisfaction with sexuality (F (3180) = 36,005; p = .001; (Wilks λ = .625), with a very strong effect (np 2 =. 375). Statistically significant results were found in sexual functioning (p = .001) with a strong effect (r^2 = .210), with an observed Power (OP) = .995, and those who reported sexual problems showed lower values of sexual functioning (14.59 ± 7.55) than subjects who did not report such problems (25.56 ± 10.26). In the subscales of self-esteem and general relations, no statisti cally significant differences were found.

When we compared the subjects in terms of physical changes such as hair loss, weight loss and the occurrence of vomiting, we found that there were no statistically sig nificant differences in all dimensions analyzed.

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to compare individuals diagno sed with cancer with healthy individuals in terms of sexual satisfaction, self-esteem, sexual functioning and quality of their general relationship. For this purpose, the following factors were considered as independent variables: type of cancer, time of diagnosis, type of treatment, and changes in body image. The latter variable was subdivided into: a) alteration to the phenotype and b) loss of limb. Other varia bles were also considered, including weight gain, fatigue, sexual problems, hair loss, and vomiting.

The results showed that individuals with a history of cancer have lower levels of satisfaction with their sexual relationship when compared with individuals with no history of cancer. These results are in agreement with past research on the issue (Flynn, et al., 2011; Gianini, 2004; Lindau, et al., 2011; Melisko et al., 2010)

We also found that different types of cancer have di fferent repercussions in terms of sexuality. These results are in agreement with the literature, which shows that high levels of well-being, quality of life and satisfaction with sexuality are strongly associated with cancer (Fleury, Pantaroto, & Abdo, 2011).

Among the various cancers, urological cancer was the one that presented the lowest level of satisfaction with sexual functioning. The anatomical area involved in this type of cancer is closely associated with masculinity and its sexuality (Tran, 2011). Cancer of the digestive tract also showed low levels of satisfaction with sexual functioning. Although the digestive tract does not deal directly with the sexual organs, it performs fundamental functions for the living being, amd impairment of it as a result of cancer can lead to alterations of self-image and, consequently, influence satisfaction with sexuality. Anxiety, fears, and doubts are present and condition the daily activities of these patients, as well as relationships and social activities, as changes in body morphology may be noticeable (Paula, Takahashi, & Paula, 2009 ) or perceived as such.

Women with breast cancer also show lower levels of satisfaction in sexual intercourse, since in most cases, body image is affected in the treatment phase. However, the sa tisfaction values are somewhat higher because the effects of treatments such as loss of the breast, or part of it, with alopecia and all hormonal changes, are mostly overcome after the end of these, or as a result of reconstructive surgery and regrowth of hair. These improvements do not occur in most cases of urological cancer, where erectile dysfunction and infertility are permanent.

Duration of treatment was significantly related to levels of satisfaction with sexuality. During the first year after diagnosis, the level of sexual satisfaction is lower than that for later periods of time. In general, those receiving treatment for cancer evidenced a decrease in the level of satisfaction with sexuality. The effects of these treatments extend over time, so clinicians should work on these aspects even after the therapies have been completed (Goldfarb, et al., 2013).

No statistically significant results were found regarding chemotherapy treatment. This finding may be because most of the participants underwent chemotherapy at the same time as radiotherapy, surgery and other treatments. All treatments involve physical and mental changes in the patients and these, in turn, are reflected at various levels, but more expressively in the patients' sexuality (Remondes-Costa, Jimenez, & Pais-Ribeiro, 2012; Serrano, 2005; Siegel et al., 2012; Valério, 2007). Fatigue has been shown to be related to age, sex, type of cancer, and type of treatment received (Battaglini, et al., 2006; Diethich et al., 2006; Ishikawa et al., 2005; Gianini, 2004; McAuley et al. 2010; Siegel, et al. 2012). As our results demonstrate, fatigue has a negative effect on sexuality and sexual functioning. Patients who report having sexual problems, and those who have weight gain, loss of body limb or any other phenotypic change. In this study, the situations of loss of a limb or part of it or of an organ, whether visible or not, were considered as well as the cases in which there was a change in the phenotype due to the treatments received. Weight gain is another factor that leads to changes in phenotype, along with the loss of body limbs. These changes in body image result in decreased self-esteem of patients and lead to dissatisfaction with appearance and sexual functioning (Flynn, et al, 2011; Peréz et al., 2010; Siegel et al., 2012). Hair loss was not significantly related to level of sexual satisfaction, a finding that was not consistent with previous research. However, the fact that there are programs that allow the use of wigs can have an attenuating effect on the level of self-esteem (Cantinelli, et al., 2006; Ramirez, 2009).

Finally, we can say that the work has shown the influence that cancer has on the level of satisfaction with sexuality. We can verify that cancer has a negative influence on sexuality, especially at the level of sexual functioning.

Urological cancer patients had the lowest levels of satisfaction with sexual functioning, followed by cancer of the digestive tract and breast.

The time of diagnosis also shows an influence on levels of satisfaction with sexuality; the periods of less than 1 year and 3 to 5 years since diagnosis are the ones with the lowest values of satisfaction with sexual functioning.

Radiotherapy, surgery and other types of treatment also have a negative effect on satisfaction with sexuality. Although our study did not find an influence of chemothe rapy on sexuality, previous research has.

Changes in body image such as phenotype changes, limb loss, which includes loss of a limb or organ, even if it is not visible externally, weight gain, fatigue, and sexual problems/dysfunctions, influence the level of satisfaction with sexuality. However, weight loss, vomiting, and hair loss have not been shown to influence sexuality.

text in

text in