Studies have extensively addressed parent-child interactions and the influence of maternal health on child behavior (Conners-Burrow et al., 2016; Zalewski et al., 2017), considering that these two condition favor difficulties. In addition, according to Simon and Brooks (2017), families living with mental health problems are frequently assisted by child protection services.

When assessing the association between children's behavior problems and co-parenting, Souza and Crepaldi (2019) highlighted the relevance of family dynamics as a protection factor to children's mental health, emphasizing the diversity of family factors involved.

Interest in maternal depression is explained by its high prevalence among women of childbearing age. For example, Brazilian studies report a rate of depression of 39.4% among women, in community samples, while international studies report up to 38% (Silva et al., 2018). In addition to its high rate, depression affects global functioning, including the individuals' ability to take care of daily tasks, decreasing productivity at work (World Health Organization -WHO-, 2021). Depression in women who are mothers affects child-care and the performance of tasks that motherhood requires.

Additionally, mental health problems during childhood have also gained relevance. According to Aguiar et al. (2018), the presence of children in psychology and psychiatry services has become increasingly recurrent. The previously mentioned authors compared similarities and differences among patients, noting that the children of mothers with moderate levels of depression measured by the Beck's Depression Inventory more frequently presented behavior problems. When left untreated, these problems may aggravate and compromise child development. There is a recognition that behavior problems are inversely proportional to social skills, as adaptive resources (Elias & Amaral, 2016; Fernandes et al., 2018).

Many studies report that demographic variables such as family income, marital status, and education influence children's behaviors (Ameen et al., 2019; Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019; Hastuti et al., 2021), in addition to the children's sex and age (Ameen et al., 2019). Hence, parents in a stable union and with a higher educational level more frequently adopt positive practices, possibly because they have the support of their partners and enjoy greater access to information. Potential implications regarding sex include the fact that behavior problems are more frequently identified among boys (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019; Cosentino-Rocha & Linhares, 2013) while girls more frequently present social skills deficits, for instance, in offering help, taking the initiative and communicating positively, which does not imply that boys do not have any social skills difficulties (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2016; Leman & Bjornberg, 2010), both among preschoolers and school-aged children (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2016).

In general, both the sex of children and their school grades are associated with behavioral problems, which can make it difficult to understand independent influences. Assis-Fernandes and Bolsoni-Silva (2020) worked with a group of 20 mothers and 20 children without behavior problems evenly distributed between girls and boys. In these conditions, the study showed that the children's sex did not influence parenting; instead, parenting was influenced by the children's behavior problems measured by a golden-standard instrument. The authors of the aforementioned study reported that the group of mothers of children with behavior problems more frequently presented a deficit in positive parenting and an excess of negative parental practices. In addition, children who had poor social skills were more likely to complain of problems, and their mothers were more likely to have depressive symptoms. Additionally, the children who presented poor social skills, more frequently elicited complaints, and the mothers presented depressive symptoms. They also found that children without behavior problems were more socially skillful and elicited fewer complaints, while their mothers statistically presented fewer depression indicators and adopted improved parenting practices, i.e., mothers of children without behavior problems, according to a diagnostic instrument (CBCL), reported that their children seldom presented disapproving behaviors. These mothers more frequently adopted positive practices when interacting with their children, such as dialogue and affection.

Family variables such as income, education, and setting are known to influence children's behavior. In this sense, Algarvio et al. (2013) found that parents with higher education are more concerned about their children's development. On the other hand, some studies report that parents' low educational level and low income increase the risk of problematic behaviors in their children (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019), which are associated with a small repertoire of positive practices and more frequent use of negative practices by parents (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019). A two-parent family configuration is considered positive; empirical indicators show that living with both parents reduces the risks imposed on child development (Crestani et al., 2013). Fraenkel and Crapistick (2016) indicate that bi-parental families more commonly present protective factors such as a double source of economic resources and psychological and social resources. Therefore, these parents usually enjoy greater social support, more significant financial flow, and economic security and can distribute roles more competently.

Undoubtedly, the demographic and mental health variables of families and children are not the only measures considered when addressing child development; however, the studies previously mentioned indicate that these variables influence parenting, which in turn, influences children's behaviors. Mendez et al. (2019) approached mother-son, mother-daughter, father-son and father-daughter pairs in order to identify the perceptions of mothers, fathers and their adolescent children about parenting practices and positive and problematic behaviors. The results indicated that parents have different expectations regarding their children's behavior depending on their sex.

When considering rearing practices, a clear relationship is identified between positive practices and children's social skills (Assis-Fernandes & Bolsoni-Silva, 2020; Charrois et al., 2020) on the one hand, and an association between negative practices and behavior problems on the other (Cicchetti & Handley, 2019). However, studies do not always pair demographic variables to verify their impact on rearing practices. Positive practices involve authority and positive discipline (Rajyaguru et al., 2019), which implies non-violent strategies to establish limits associated with positive parental involvement (Baker et al., 2018), providing the child with affection and attention. On the other hand, negative parenting practices include not being very sensitive to the child's needs (Bödeker et al., 2019), authoritarian discipline, and physical punishment to regulate a child's behavior (Gershofft & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016).

From a mental health point of view, the influence of maternal depression on children's behavior (Conners-Burrow et al., 2016; Zalewski et al., 2017) and parenting is well documented in various studies (Dow-Fleisner, 2017; Infurna et al., 2016; Vafaeenejad et al., 2018; Zalewski et al., 2017). For instance, Saputra et al. (2017) conducted a predictive cross-sectional study and found that negative family relationships, maternal depression, parenting, and academic competence impact mental health problems in school-aged children.

The literature review lists many variables that influence behaviors and maternal parenthood. Sociodemographic variables are considered to be predominant in the interaction between child behavior problems and maternal mental health. Thus far, no studies have addressed the influence of some sociodemographic variables on maternal rearing practices and the behaviors of preschool and school-aged children in a typical sample. The present study included children from a typical sample that met the following criteria: mothers without maternal depression and children with behavior problems systematically assessed. The aim of the study refers to this context, that is, to verify how the sociodemographic variables of mothers and children are associated with maternal parenting practices and the children's behavioral skills or problems from the mothers' perspective. A typical sample of children systematically assessed as not having behavioral problems and mothers without current indicators of depression was selected. Addressing these variables together can support knowledge, bearing in mind that that regarding parenting practices, behaviors are influenced by multiple factors (Costa & Fleith, 2019). Hence, considering the review, the following hypotheses are proposed: (a) positive associations between positive parenting practices and social skills, regardless of the children's age and sex; (b) positive associations between negative parenting practices and complaints of behavior problems regardless of the children's sex and age; (c) positive associations with girls' social skills and boys' behavior problems; and (d) positive associations with mothers' higher educational level and income.

The objective was to identify associations between the sociodemographic variables (children's age, mothers' age, number of children, family income) of children and mothers and the children's behavior indicators (resources or problems) in a sample of children without behavioral problems and mothers without current depression indicators.

Method

Type of study

A quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive, and correlational study was performed (Meltzoff, 2001).

Participants

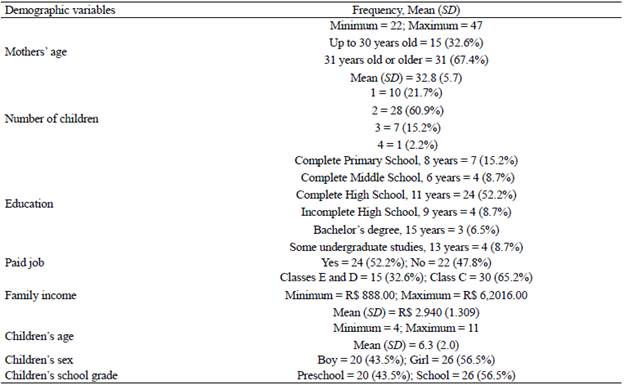

The study involved forty-six pairs of biological mothers who lived with their partners and children. The mothers were married and healthy, and their biological children had no behavioral problems. Table 1 shows that most mothers were 31 years old or older (67.4%), had two children (60.9%), had completed high school (52.2%), and belonged to socioeconomic Class C (65.2%), which is considered within the average of the general population, according to government data resulting from the population demographic census (Fundación Getúlio Vargas -FGV-, 2018). Classes E and D have fewer economic resources and are considered more socially vulnerable. Gender and school grades of children were evenly distributed, as well as whether mothers were in paid work.

Sampling

A sample of 46 participants was selected from a larger sample based on the criteria described below. This study involved a Brazilian convenience sample of 151 biological mothers and their children: 77 preschoolers and 74 school-aged children attending municipal nursery schools and 17 primary schools located in a medium-sized city in São Paulo, Brazil. A total of 426 families (192 preschoolers and 234 school-aged children) were invited after the schools nominated one child with behavior problems and one child without behavior problems. The families of 96 preschoolers and 135 school-aged children refused to participate due to a lack of time or interest. A total of 195 families (96 preschoolers and 99 school-aged children) answered the instruments. Forty-four respondents were excluded for being the fathers (21), grandmothers (13), or aunts (10); the objective was to work only with the 151 biological mothers. Of these, 38 preschoolers and 41 school-aged children presented behavior problems and were excluded. Finally, 14 mothers were excluded due to the scores obtained on the PHQ-9 as they were considered clinical subjects, in addition to 12 children who were outside the age group included in this study.

Inclusion criteria were: (a) mothers who did not present current depression indicators according to the criteria proposed by the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire -9 -Osório et al., 2009) and who were in a marital relationship; and (b) children who did not present clinical indicators for the problems measured by the CBCL (Child Behavior Checklist, Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The children were aged between 4 and 11, i.e., preschoolers and children attending primary school. Bias was controlled by exclusively including biological mothers living with their partners to avoid heterogeneous family configurations and facilitate the identification of the influence of socio-demographic variables under similar conditions. Note that multiple family configurations have recently been found, which are not considered a problem in themselves; the structural and internal dynamics of families are the factors that contribute to family outcomes (risk or protective factors) (Walsh, 2016).

Instruments

Roteiro de Entrevista de Habilidades Sociais Educativas Parentais (RE-HSE-P, Bolsoni-Silva et al., 2016) [Parenting Social Skills Interview Guide] is a semi-structured interview that describes the interactions between parents and children. It includes 14 open-ended questions to assess practices (positive and negative), children's behaviors (problem complaints about problems, social skills), and contextual variables (e.g., whether the mother has conversations with the child on a variety of topics at different times of the day). Practices are related to communication, limit-setting, and expression of feelings based on children's behaviors.

In addition to providing a general measure of both mothers' and children's behaviors, a qualitative analysis of the instrument enables investigating the following positive practices: talking about the child's interests, expressing affection, providing explanations, complimenting, establishing rules, providing encouragement, playing, and having a good time. Conversely, negative practices include aggressively expressing negative feelings, not keeping promises, spanking, cursing, threatening, yelling, getting angry, intimidating, saying no without explanations, and growling. The RE-HSE-P presents two factors: Factor 1 -Total positive (Alpha= .827) and Factor 2 - Total negative (Alpha= .646). The instrument differentiates children with and without behavior problems. It provides risk indicators characteristic of a clinical sample as opposed to a lack of risk indicators at a non-clinical level for children's social skills, positive parenting, complaints of behavior problems, and negative parenting (Bolsoni-Silva et al., 2016). This instrument also measures the sociodemographic variables adopted in this study, as described below.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is rated on a Likert scale and is directed to preschoolers and school-aged children (6 to 18 years old). The families answer 113 questions addressing behavior problems. The results are organized into internalizing, externalizing, and total problems, in addition to problem/disorder subscales. Psychometric studies identified satisfactory criteria for positivity-test and morbidity for clinical and non-clinical profiles (Bordin et al., 2013), including the Brazilian population. The psychometric studies in the Brazilian sample identified high sensitivity of the instrument with other gold-standard instruments (CID-10, DSM - IV), which have been used in epidemiological studies to measure the results of interventions, showing satisfactory discriminant and convergent validity.

Therefore, this instrument was used as a reference measure of behavior problems to differentiate between children with and without problems. The exclusion criterion was having behavior problems classified as clinical or borderline in at least one of the general scales (internalizing, externalizing, total); only children without behavior problems were kept in the sample.

The Brazilian version of PHQ-9 - Patient Health Questionnaire (Osório et al., 2009). The PHQ-9 is a module based on DSM-IV criteria for Major Depression Disorder rated on a Likert scale. It was proposed and validated by Kroenke et al. (2001) and enables screening signs and symptoms of current Major Depression. A psychometric study was conducted in Brazil (Osório et al., 2009), and the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV was used as the gold-standard instrument, which presents excellent validity, showing an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.998 (p<.001). A cut-off point equal to or higher than 10 was considered the most appropriate for screening depression with 100% sensitivity and 98% specificity. Because it is a screening of depression indicators, when privileging maximum sensitivity, the cut-off point is valuing the identification of more individuals who need mental health care (Szklo & Javier Nieto, 2007). The sample was composed only of women who did not score for depression.

Socio-demographic variables. Before applying the RE-HSE-P, the demographic information concerning the children, mothers, and families was collected. Then, according to the guidelines proposed by an official agency, family income was classified into income levels (times the minimum wage) and categorized into economic classes according to the guidelines proposed by an official agency (FGV Social, 2018).

Ethical Aspects

This study is part of a larger project titled Raising practices of fathers, mothers, and teachers of children with and without behavior problems differentiated by sex and education, considering reports and observations (CAAE: 83049618.0.0000.5398), approved by the Ethics Committee Board at the hosting university. Data were collected after the mothers provided their written consent-the informed consent form provided information regarding potentially unpleasant experiences.

Data Collection Procedures

After approval from the Early Childhood Education Department, 17 nursery schools and 12 primary schools evenly distributed over the city were contacted to assess an equivalent number of both types of schools in all the regions. The objectives of the study were presented to schools' principals or teaching coordinators, and the teachers were invited to participate after authorization-those who accepted signed free and informed consent forms. Teachers designated one child with behavioral problems and one without problems. Such a perception was confirmed with a validated instrument (CBCL); therefore, children whose assessment confirmed the presence of behavioral problems were excluded from the sample of this study.

The families who consented to participate also signed free and informed consent forms, and a trained researcher personally interviewed the families at their place of choice (at home or school). The application of the instruments took approximately one hour.

Data processing and analysis

After selecting the sample according to the inclusion criteria (i.e., mothers with no indicators of depression as measured by the PHQ-9 and children with no behavioral problems according to the CBCL), data collected with the RE-HSE-P were tabulated according to the guidelines. First, descriptive analyses were performed with demographic variables, and risk and non-risk indicators for parenting practices were verified (positive and negative practices) in addition to the children's behaviors (complaints and social skills). Next, Spearman's correlation test was performed because the sample did not meet normality criteria (Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test). Finally, parenting practices and children's behaviors were compared according to the children's sex and school grade (Chi-square). The significance level was set at 5%. The correlations were classified according to Marôco (2014) as: weak (0- .25), moderate (.26-.50), strong (.51-.75), or very strong (≥75).

Results

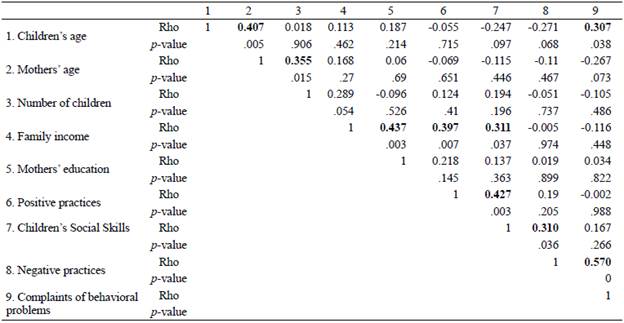

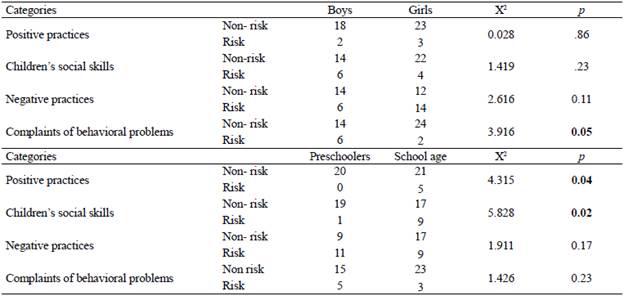

Table 2 presents the practices, social skills, and behavior complaints indicators. The correlation results are presented in Table 3, and Table 4 presents comparisons considering the children's sex and school grade.

Table 2 Frequency of risk and non-risk indicators for parenting practices and children's behaviors (n = 46)

| Risk | Non-risk | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive practices | 5 (10.9%) | 41 (89.1%) |

| Negative practices | 20 (43.5%) | 26 (56.5%) |

| Children's social skills | 10 (21.7%) | 36 (78.3%) |

| Behavioral complaints | 8 (17.4%) | 38 (82.6%) |

Table 3 Correlation between maternal sociodemographic variables, parenting practices, and children/s behaviors (n = 46)

Table 4 Comparisons (Chi-Square) between parenting practices and children's behaviors according to sex and school grade (n = 46)

Table 2 shows that this study's sample adopted both positive and negative parenting practices when interacting with their children. Note that risk-free positive practices were more frequent than negative practices (89% and 56.6%, respectively), although some mothers had poor positive practices (10.9%) and more than 40% adopted negative practices frequently enough to pose some risk to child development.

Most of the children's behaviors were not risky: 78.3% had a satisfactory social skills repertoire, and only 17.4% had risky behaviors as measured by the RE-HSE-P. Like the mothers, some children had poor social skills (21.7%) and provoked complaints.

Table 3 shows moderate to strong correlations for the evaluated behaviors. Regarding the study's variables of interest, the older the child, the more frequently the mothers' complaints. Income was positively associated with the mothers' educational level, the repertoire of positive practices, and the children's social skills. As expected, positive practices were associated with the children's social skills, while negative practices were associated with behavioral problems. However, the children's social skills were also associated with negative practices.

Positive practices and negative practices were equally adopted among boys and girls (Table 4). Although the test did not present any statistical difference, it was verified that most of the negative risk practices were implemented in interactions with girls. As for complaints about behavioral problems, few complaints are considered risky. The statistical test indicated a higher risk among boys and no risk among girls, a difference that concerns the children's sex.

As previously noted, few children and mothers (n=10; n=5, respectively) presented deficits in social skills and positive practices. Table 4 shows the distribution of these children according to school, and negative practices and complaints of behaviors did not differ according to age.

Discussion

Considering the aim of this study, its focus on a typical sample, where the mothers were married, healthy, and their biological children did not present behavioral problems, and having controlled for risk factors, an association was found between children's behaviors and the interactions established between mothers and children, taking into account some socio-demographic variables of mothers and children.

According to Souza and Crepaldi (2019), these results show the influence of other uncontrolled factors even in a sample of typical children and families, revealing a multiplicity of factors involved in family dynamics.

The results show that the profile of the mothers is similar to that reported in the literature: most mothers (approximately 60%) were older, had few children, and had a high educational level and income (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019). Note, however, that mothers with lower educational levels, low incomes, or a larger number of children did not present indicators of depression, and their children did not present behavior problems. Hence, the mothers' demographic variables influence parenting and children's behaviors but are not the only variables at play, indicating the multifactorial nature of both (Costa & Fleith, 2019). Some of the mothers addressed in this study had a paid job, while a similar number of mothers did not. Additionally, the children were similarly distributed in terms of sex and school grade, variables that determined the sample's homogeneity.

Because this can be considered a typical sample, i.e., there are no indicators of current maternal depression and no behavior problems among children, it was expected that the frequency of positive practices would be greater than negative practices and that the children's social skills would be more abundant than the complaints (Assis-Fernandes & Bolsoni-Silva, 2020; Charrois et al., 2020; Cicchetti & Handley, 2019). This study confirmed those expectations; however, almost half of the sample presented negative risk practices. Such practices may be related to Brazilian culture where negative parenting practices are adopted, and parents tend to be more tolerant of boys than of girls. Considering exclusively the assessments of mother and sons, the results found in this study are similar to those reported by Méndez et al. (2019) regarding the adoption of parenting practices according to the child's sex and a tendency to adopt negative practices with girls more frequently.

This finding is consistent with Hastuti et al. (2021), who reported that 44% of the sample did not accept and punished their children's behaviors equally between boys and girls; no significant differences were found in this study regarding the use of negative practices between boys and girls. In any case, it is a warning for the risk posed to child development, suggesting that culture plays a role and influences the adoption of negative practices when disciplining children even when they do not present clinical indicators for behavior problems. Bolsoni-Silva et al. (2016) found that negative practices were adopted in the interactions established between parents and children with and without problems, though negative practices were more frequent among children with behavior problems; Assis-Fernandes and Bolsoni-Silva (2020) also report this finding. Approximately 20% of the children presented poor social skills and more frequently elicited complaints, which may be related to excessive negative practices (Charrois et al., 2020; Cicchetti & Handley, 2019). Note that the analysis presented here focuses on each of the variables. However, one cannot lose sight of the fact that many social determinants and contextual variables contribute to actions within family interactions, such as the multiple roles played by women and the different dynamics that can take place within families regardless of their configurations (Walsh, 2016). Similarly, teaching social skills is a role that is not restricted to families. The school is very relevant for children to acquire these skills during this developmental period (Coura & Pinto, 2021).

The analysis of correlations confirmed that school-aged children more frequently elicited complaints (Bolsoni-Silva et al., 2016) and that family income and the mothers' educational level were associated with an improved repertoire of positive practices (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019). Additionally, a higher income was directly proportional to the children's social skills (Ameen et al., 2019; Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019). Therefore, considering the association between positive practices and children's social skills, one may assume that income ensures greater access to information, encourages positive parenting, and promotes social skills.

Negative practices were strongly associated with complaints of behavior problems (Charrois et al., 2020; Cicchetti & Handley, 2019), indicating that children's behaviors and parenting practices (Assis-Fernandes & Bolsoni-Silva, 2020) maintain a bidirectional relationship of practices and behaviors. An association between negative practices and children's social skills was also found, suggesting that negative practices are adopted even in non-clinical samples, contingent on socially skillful behaviors, confirming the mothers' difficulties in raising children and consistently implementing parenting practices. Therefore, as reported by other studies (Ameen et al., 2019; Assis-Fernandes & Bolsoni-Silva, 2020; Bolsoni-Silva et al., 2016; Charrois et al., 2020; Cicchetti & Handley, 2019), positive and negative practices, complaints of behavior problems and social skills coexist in clinical and non-clinical samples. Differences lie in the frequency and diversity of behaviors expressed in the interactions between mothers and children.

In line withAssis-Fernandes and Bolsoni-Silva (2020), the comparison of parenting practices and children's behaviors according to the children's age revealed few differences. The previously mentioned authors found no differences regarding parenting practices and children's behaviors (complaints and social skills) when addressing a clinical and a non-clinical group for behavior problems, when controlling for sex. However, as reported by other studies, complaints were more frequent among boys (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2019; Cosentino-Rocha & Linhares, 2013). In addition, social skills did not differ between boys and girls, which is opposed to what other authors have found (Bolsoni-Silva & Loureiro, 2016; Leman & Bjornberg, 2010). This finding may have resulted from the method used in this study, as none of the children belonged to a clinical group. For this reason, all the children were expected to be equally skillful, considering that behavior problems and social skills are inversely proportional (Elias & Amaral, 2016; Fernandes et al., 2018).

Regarding the influence of the children's age, even though the analysis of correlations revealed that school-aged children more frequently elicited complaints of behavior problems, the comparison analysis (considering the occurrence of clinical/risk and non-clinical/non-risk indicators) showed no differences between school-aged children and preschoolers in terms of the use of negative practices and complaints of behavior problems. This finding is opposed to the results reported by other studies (Bolsoni-Silva et al., 2016). Few mothers and children presented poor social skills, but note that these were school-aged children, suggesting this might be a more challenging period in child development.

Limitations

Limitations of the study are the cross-sectional design, the small sample and belonging to a single context, without equivalence and differentiation regarding the mothers' income and educational level, as well as having mothers as exclusive informants and only depression screening measures. Hence, future studies are suggested to address more robust samples, differentiated by the families' level of education and income, adopting observational measures and longitudinal designs. Additionally, future studies can address other informants and adopt diagnostic measures to assess depression and other disorders, considering that only one screening instrument was used in this study.

Contributions

This study addressed a sample considered typical according to specific criteria; it included mothers without current depression and children without behavior problems. The results show that positive practices were associated with the children's social skills and that mental health resources protect but do not exclude negative practices when interacting with children; hence, teaching positive practices is crucial for prevention. In contrast, negative practices were associated with complaints of behavior problems. Even though few children presented poor social skills or exhibited excessive behavior problems, almost half of the sample adopted a high level of negative practices. The mothers' demographic variables, educational level, income, age, and the number of children seem to favor a lack of behavior problems. The children's sex and school grade influenced complaints of behavior problems and social skills (of both mothers and children), respectively. Note that this study's sample was selected from a specific social context, i.e., Brazilian bi-parental families, most of whom belong to the middle class with moderate economic resources.

The results suggest that preventive interventions implemented among parents and children are also relevant in typical populations to prevent the risk of behavior problems among children, and mothers' depressive symptoms when facing problems interacting with their children.