Introduction

Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Strongylida: Metastrongyloidea) is a helminth characterized by a resistant external cuticle, unsegmented body, and a completely developed gastrointestinal tract. It belongs to the Order Strongylida, Superfamily Metastrongyloidea, which includes Ancylostoma nematodes, a long, thin, fliform worms that reside in the host´s lungs (Vitta et al. 2011). The first report of the presence of Angiostrongylus in humans was made by Nomura and Lim (1945), who detected A. cantonensis in the cephalorachidian liquid of a Taiwanese patient with eosinophilic meningitis.

Like all Metastrongyloidea worm species, A. cantonensis adults inhabit the pulmonary arteries of rats and mice (Anderson 2000), where females lay eggs from which first sta ge (L1) larvae emerge. These L1 larvae migrate towards the pharynx and are swallowed and eliminated through feces. Once in the outside environment they invade a habitual intermediate host, among which are terrestrial mollusks such as the giant African snail (Lissachatina fulica). Larvae go through two molts inside this host over an approximate period of two weeks. When they reach the third stage (L3) they can infect their definitive host. Once inside the host, the L3 migrate to the brain where their development continues until reaching the young adult stage (L5). This process can occur within a 4-week period. The young adults return to the venous system to reach the pulmonary arteries, where after two weeks they reach sexual maturity and can begin laying eggs (Dorta et al. 2007).

Humans are considered accidental A. cantonensis hosts. This parasite can enter their system as a result of the ingestion of snails, of vegetables infected by snail secretions, or of other paratenic hosts such as terrestrial crabs or shrimp. A. cantonensis larvae can reach the brain, and on rare occasions the lungs or the eyes (Dorta et al. 2007, Thiengo et al. 2010). Once inside the central nervous system (CNS), the A. cantonensis larval movement produces meningoencephalitis with a proteiform clinical picture, characterized by its association with an important increase in blood eosinophils and cephalorachidian liquid (CRL); if it moves into the eyes it causes permanent blindness in the patient (Alicata 1991, Jarvi et al. 2012, Londoño et al. 2013).

In less than 10 years the giant African snail has been reported in over 70% of Colombia´s departments. It has been associated in particular with urban centers, in which it finds refuge and food in gardens, road medians, green areas, empty lots, abandoned building sites, or places where organic material has accumulated (De la Ossa et al. 2012, 2014, Bolivar et al. 2013, Giraldo et al. 2014, Avendaño & Linares 2015, Patiño & Giraldo 2017). Recently, Córdoba et al. (2017) reported the presence of three genera of nematode parasites (Angiostrongylus, Aelurostrongylus, and Strongyluris) associated with giant African snail specimens collected in nine cities of the Valle del Cauca, Colombia: Jamundí, Cali, Palmira, Buga, Tuluá, Bugalagrande, Cartago, Dagua, and Buenaventura. owever, these authors do not confirm the specific presence of A. cantonensis in the samples reviewed.

Methods

Samples

In order to confirm the presence of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in individuals of the giant African snail, 19 individuals of L. fulica were collected opportunistically in the continental area of the city of Buenaventura following the recommendations of manipulation stablished by the Ministry of Environment and sustainable development (MADS, 2011). Individuals were transported to the Animal Ecology Laboratory of the Universidad del Valle, where they were sacrificed and preserved following recommendations from MADS (2011).

Histological techniques

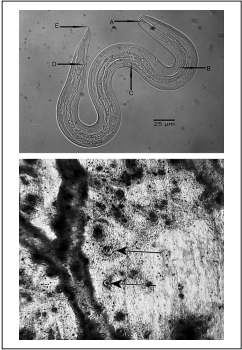

Lung tissue was extracted and a visual search was conducted using a stereoscopic microscope to quantify the number of free-living and cystic A. cantonensis larvae. Larvae were identified based on characteristics described for the species by Ash (1970) and Lv et al. (2009).

DNA extraction and PCR

To confirm molecularly the taxonomic identity, DNA extraction was done from lung tissue pieces as well as the nonencysted individuals using the “Wizard Genomic Purification” kit following of manufactural instruction. A. Cantonensis parasites were detected by both conventional and real-time PCR techniques using specific pair-primers designed for the ITS1 ribosomal DNA region of A. cantonensis

The pair-primers were obtained with the online software Primer3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/) using as reference nucleotide sequence: GU587760, available in the GenBank collection. The primers sequences were: AcanITS1Revers 5’-TTC ATG GAT GGC GAA CTG ATA G-3 ‘and AcanITS1Forward 5’-GCG CCC ATT GAA ACA TTA TAC TT-3’. One of the sample positives using the specific primers for A. cantonensis was sequenced by the Sanger method to verify the parasite taxonomic identity using blast analysis-NCBI. Afterward, this sample was used as positive control in the experiments. Also, the free PCR mixture was used as a negative control (Garzon et al. 2017).

Results

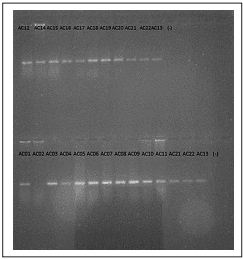

Using a histological technique for direct observation, a total of 17 cysts and three free-living A. cantonensis larvae were collected and identifed in 17 of the 19 analyzed samples (Figure 1), which is equivalent to an 89% detection rate. All samples had an identical nucleotide sequence and showed the highest percentage identity with the KP776415.1 A. cantonensis clone 4 (Sydney study) (100% identities, 0% gaps). The negative control failed to amplify in any of the test repetitions (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Upper panel: Free-living L3 Angiostrongylus cantonensis larva in Lissachatina fulica lung tissue. A. Rod-like structure with rounded ends in the spear. B. Excretory pore, C. Esophageal bulb, D. Anus, E. Pointed tip. Lower panel: Angiostrongylus cantonensis cysts in Lissachatina fulica lung tissue (arrows)

Figure 2 Endpoint PCR in 1% agarose gel. A fluorescent band could be observed for all samples except sample AC02. Negative controls failed to amplify.

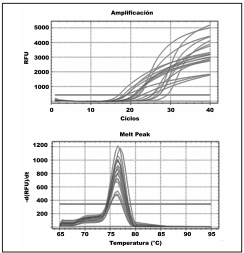

Figure 3 Upper panel: Real-time PCR results for DNA samples from Lissachatina fulica lung tissue containing Angyostrongylus cantonensis cysts. Lower panel: dissociation curves (Tm) of products amplifed by PCR. The Tm of amplifed products was between 76º and 77ºC, whereas a Tm peak was absent for the negative control

Through conventional PCR we found that 18 of 19 analyzed samples were positive for A. cantonensis presence, equivalent to a 95% detection rate. Moreover, all tissue and free-living nematode samples were positive for A. cantonensis using real-time PCR (Figure 3), equivalent to a 100% detection rate. The analysis of the melting temperature (Tm) showed the same maximum emission value for all samples, which corresponded to the Tm of the primers used (Figure 3).

Discussion

The confirmation of A. cantonensis presence in the lung tissue of giant African snail specimens from the city of Buenaventura, Valle del Cauca, in addition to the great densities of this invasive mollusk reported in urban areas of the Valle del Cauca, Colombia, (Bolivar et al. 2013, Giraldo et al. 2014) and its presence in more than 70% of the country’s departments (De la ossa-Lacayo et al. 2012), could increase the probability of exposure of human beings to the parasite load of this snail, which includes eggs and larvae of A. cantonensis. Therefore, eosinophilic meningitis could be considered an emerging disease in Colombia, as has been reported for Ecuador, Brazil, and Venezuela (Espirito-Santo et al. 2013, Solórzano- Álava et al. 2014).

In Colombia, meningitis is attributed mainly to viral infections or bacterial infections (Tique et al. 2006), excluding the nematode A. cantonensis from the possible agents of infection. However, results from the present study confirm the need to alert medical entities, which should be prepared to carry out timely interventions in case of the development of an epidemic focal point in Colombia (see Londoño et al. 2013).

Real-time PCR detection of A. cantonensis is not yet widely used in its identification, but in the present study is has been proven reliable for the detection of A. cantonensis DNA in lung tissues from the giant African snails with a new specific pairprimers. Despite that the prevalence of A. cantonensis no show statistical difference among techniques, our findings suggest that the Real-time PCR method is more eficient to assess A. cantonensis infection than conventional PCR or histology, especially when there is a small number of parasites.

The differences among methods may be explained by the sensitivity of each method. The real-time PCR is a technique used to monitor the progress of a PCR reaction in real time. At the same time, a relatively small amount of DNA can be detected. Real-Time PCR is based on the detection of the fluorescence produced by a reporter molecule which increases, as the reaction proceeds. This occurs due to the accumulation of the PCR product with each cycle of amplification (Tamay de Dios et al. 2013).

In our experiment, the fluorescent reporter molecules that bind to the double-stranded DNA was SYBR® Green. So, minimal amounts of the nucleic acid of A. cantonensis were detected accurately in the lung tissue of giant African snails. Moreover, there was no need post PCR processing like the electrophoresis in a gel, which saves both resources and time, in contrast, conventional PCR and histology need most more time, and in the case of histology also, it is necessary an expert identify the parasite by observation under a stereoscope.

The implementation of the real-time multiplex PCR technique (Varela et al. 2017) or the technique used during the present study (see Garzon et al. 2017) could become diagnostic tools that would allow the identification of the prevalence of A. cantonensis in giant African snails for a given location, so that control efforts could be directed towards this invasive species to reduce the risk of development of an epidemic focal point of neuro-angiostrongyliasis.

In conclusion, the three techniques employed identified A. cantonensis in the tissue of A. fulica collected in the city of Buenaventura, Colombia. This study confirmed for the first time the presence of A. cantonensis associated with L. fulica specimens in Colombia using histological and molecular methods.