1. INTRODUCTION

In the dictionary, self-deprecation is characterized as a devaluation of one’s qualities and capabilities (Aulete Digital, 2019). Focusing on psychological literature, the American Psychological Association dictionary defines self-deprecation as an individual tendency to belittle oneself, in a way that is not completely related to reality, and which may be associated with depressive episodes (VandenBos, 2010). More recently, Szcześniak et al. (2021) agree with this concept, describing this variable as a negative self-assessment, where people see themselves as incompetent and diminishes their own abilities.

These alternatives bring points that need to be highlighted: Self-deprecation is considered an individual phenomenon, which seems to be related to self-concept and the appreciation of one’s achievements (Aulete Digital, 2019). A more complex characterization does not seem very apparent, and its causes are unclear; Finally, self-deprecation is associated with depressive symptoms, and could be one of the behaviors exhibited by subjects suffering from this psychopathology (VandenBos, 2010).

However, despite the relationship with identity and mental health damages indicated by previous concepts, self-deprecation is rarely addressed in psychology, not being clearly defined in the scientific literature. Some scarce examples of more recent research in this topic are Beer et al. (2013), in their research on social comparison (however, at no point the study discusses a clear definition of self-deprecation). In another study regarding social comparison, Lee & Park (2021) observed that self-deprecation mediated the relationship between upwards social comparison and depressive symptoms on middle school students.

Santos et al. (2019), on the other hand, initiate a reflection on the construct using their research on music impact as a basis. The results indicated that a song with self-deprecating content might lead the consumer to have more negative cognitive associations and affects, as well as less positive affects. To properly select and discuss the topic, the authors characterized self-deprecation as a set of negative beliefs and affects towards oneself (Santos et al., 2019). Finally, Szcześniak et al. (2021) observed that self-deprecation, as a negative self-presentation style, mediated the relationship between self-esteem and life satisfaction.

Thus, it is necessary to start a systematic discussion around this concept, and considering the lack of bibliography focused exclusively on this theme, it is possible to begin by introducing two constructs that can offer some insight about a better conceptualization of self-deprecation: self-esteem (a field where self-deprecation started to be discussed more consistently) and malignant self-regard (recent construct of the personality psychology field that relates the way we evaluate ourselves and psychopathological disorders) (Lengu et al., 2015; Owens, 1994).

Self-esteem is conceptualized as the subjective assessment that a subject makes about their value as a person (Harter, 2006; Orth, 2017). As highlighted by Brown (1993), the emphasis of this construct is on an affective aspect rather than a cognitive one, which means that high or low self-esteem is more related to affect towards oneself than to a rational reflection of a person’s positive or negative characteristics. This construct is capable of predicting other psychosocial aspects.

Carter (2018), for example, points out that stable self-esteem in adolescence is a predictor of greater frequency in the practice of physical exercises, also being a protective factor of stressors that could lead to a less healthy lifestyle at this stage of development. On the other hand, having low self-esteem is related with difficulties in maintaining a job, the development of depressive symptoms, and excessive use of social networks, thus demonstrating that the way we evaluate ourselves can impact different areas of our personal and social life (Huysse-Gaytandjieva et al., 2015; Woods & Scott, 2016).

However, characterizing self-deprecation as merely low self-esteem may not provide a sufficient explanation for issues of such complex nature. Owens (1994) already argued about the possibility of self-esteem having two facets: the positive one being the traditionally conceived view of self-esteem; and the negative self-deprecation, which would be the degree in which a subject decreases their value and capacity critically and negatively. In his study, considering this separation between the positive and negative aspects of self-esteem, the author was able to detect more subtle differences in the results than were usually reported in investigations covering the same topic.

But despite Owens (1994) considerations about self-deprecation being valuable to start the discussion, the author still places self-deprecation as something: 1) strictly affective/self-evaluating; 2) only as a self-esteem facet. However, a more recent line of research presents malignant self-regard (Huprich, 2014), an alternative to understanding a group of personality disorders that had been left out of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders despite strong empirical evidence. They are the Depressive, Masochistic, Self-deprecating, and Vulnerable Narcissistic Personality Disorders (Lengu et al., 2015). Thus, malignant self-regard is a set of common characteristics, a personality construct that would more likely present in individuals who suffer from the previously mentioned disorders (Huprich, 2014).

The characteristics composing malignant self-regard are exacerbated perfectionism and self-criticism, a high need for approval and recognition, constant feelings of guilt and shame, feeling inadequate, a tendency to develop depressive conditions, difficulties in maintaining self-esteem, sensitivity to criticism, and inability to control anger and frustration (Huprich & Nelson, 2014). Additionally, these individuals would more likely have poor emotional regulation and difficulties in maintaining stable and meaningful relationships, caused by their troubled view of their value (Evich, 2015).

Considering this information, it is not surprising that Huprich and Nelson (2014) found a high negative correlation (r = -0,64) between malignant self-regard and Rosenberg self-esteem scale (1989). Beyond that, contrary to self-esteem, malignant self-regard goes far beyond the affective aspect of the self-view. Thus, Huprich’s (2014) contribution to the understanding of self-deprecation comes from offering a series of characteristics that can be related to this theme, especially the tendency to depressive symptoms and the feeling of inadequacy and never being enough.

Based on previous literature, we propose a conceptualization for self-deprecation, tracing differences between the previously mentioned themes. Self-deprecation can be defined as an attitude (evaluation composed of affective, cognitive aspects and intention to behave) characterized by: affectively, negative feelings towards self (the aspect that would be closest to a “negative” version of self-esteem); cognitively, a set of beliefs about one’s inability, a view of oneself as useless, worthless or unprepared for daily activities; and behaviorally, avoidance of success, procrastination and inability to accept recognition for their deeds.

Therefore, unlike self-esteem, self-deprecation would not be centered exclusively on an affective component, extending to cognitive and behavioral patterns (Brown, 1993). Besides, it would also differ from malignant self-regard because it is a subclinical attitude, not necessarily associated or a predecessor of a psychopathological disorder.

Another way of understanding the characteristics of self-deprecation would be through its correlations with other constructs. In addition to self-esteem, aggressiveness and narcissism will be addressed. Aggressiveness shows mixed relationships (both negative and positive) with self-esteem and a positive relationship with depressive symptoms, which can indicate positive relationships with self-deprecation (Barry, McDougall, Anderson & Bindon, 2018; Krygsman & Vaillancourt, 2019). Narcissism, in addition to having a consistent relationship with self-esteem, could also be negatively related to self-deprecation because it represents an extreme self-worth (Hart, Richardson & Breeden, 2019).

2. THE PRESENT STUDY

With that said, empirical evidence is needed to demonstrate the validity of the self-deprecation construct, as well as to observe other psychological issues with which it relates. Additionally, considering that previous studies usually use the Rosenberg Self-esteem scale to measure this construct (e.g. Lee & Park, 2021), the development of a specific instrument for assessing self-deprecation is necessary.

In the present research, the relationship between self-deprecation and two themes, in particular, will be also analyzed: narcissism and aggression, as said topics already show signs of having a relationship with self-esteem (e.g. Barry et al., 2018; Hart et al., 2019; Rahayu & Hamid, 2021; Kinrade & Lambert, 2022), thus assisting better differentiation between self-esteem and self-deprecation. Thus, this research aimed to:

Develop and validate an instrument that measures self-deprecation;

Observe said instrument’s correlations with self-esteem, narcissism and aggressivity (aiming to analyze convergent validity).

2.1. Study 1: Determining the Factor Structure of the Scale

2.1.1. Participants

200 Brazilian volunteers from the general population responded to the survey, mostly students (64,5 %) female (76,5 %), middle class (45,5 %), and single (53 %). The average age of the participants was 21,6 years (SD = 6,05), despite the fact that the highest concentration was shown to be of participants with 19 years (21,5 %). The age range was between 18-51 years. It was a convenience sampling. To participate in the study, it was necessary to be 18 years of age or older and to be able to understand the research instructions.

2.1.2. Instruments

Self-Deprecation Scale. Developed in the present study, initially having 15 items, that described behaviors (e.g., I tend to procrastinate), beliefs (e.g., I have more flaws than most people) and feelings (e.g., I am often frustrated with my own attitudes). It is answered with a Likert response scale. The psychometric indices will be presented in the Results section.

Sociodemographic Questions. In order to characterize the sample, participants were asked about their age, gender, profession and economic class.

2.1.3. Procedures

First, the scale development procedures were carried out: Items were written based both on the operational definition elaborated and the previous literature. Two psychologists with expertise on psychometric instruments reviewed the developed items, selecting those that best fit the operational definition. Besides, before the actual application, the scale was presented to five members of the general population, to determine whether the sentences were understandable. There were no related difficulties.

The application of the study was carried out in two ways, in person and virtually. In face-to-face applications, a properly trained researcher asked volunteers to answer questions in a printed booklet, using public (e.g., class- rooms) and private (e.g., home) spaces. In the virtual application, a form developed in Google Forms was used, which was shared on social networks such as Facebook and Instagram. Finally, it is noteworthy that both collection procedures followed the Brazilian ethical guidelines regarding research with human beings: Not only was the project approved by the designated ethics committee, but participants also provided informed consent concerning their participation.

2.2. Data Analysis

R was used to analyze the collected data, specifically the psych statistical package (Revelle, 2017), to perform: descriptive analyzes (to characterize the sample); the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (KMO) and the Bartlett sphericity test (seeking to see if the data collected were adequate for further analysis); polychoric correlation and parallel analysis (to analyze the factorial organization of the scale); and McDonald’s Omega (in order to verify the instrument’s reliability). The figures were made using the semPlot package (Epskamp & Stuber, 2017).

3. RESULTS

Firstly, KMO and Bartlett’s sphericity test were performed. They obtained the values of 0,88 and 764,05, respectively (p < 0,001), considered by the literature as satisfactory. The sample was then considered suitable for factorial analysis.

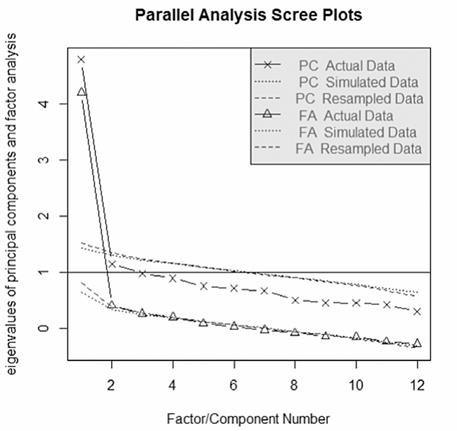

Concerning the factorial organization, observing the polychoric correlation matrix for ordinal data it was possible to demonstrate an unifactorial organi zation, with an eigenvalue of 4,20 that explained 35 % of the variance. This model was verified and confirmed using Cattell’s criteria (dispersion diagram), Horn’s criteria (parallel analysis) and Bootstrapping (resampling) (Figure 1).

The factorial loads supported the previous results, with all items included in factor 1 with values above 0,30. The highest value was item 3 (0,74) and the lowest was item 11 (0,30), as it can be seen in Table 1. Finally, McDonald’s Omega was measured to verify the reliability of the scale, obtaining the value of ω = 0,89, thus being psychometrically adequate (Revelle & Zinbarg, 2009).

Table 1 Factorial Loadings

| ITEMS | ITEM MEAN (DP) | FACTORIAL LOADING | COMMUNALITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1- I tend to procrastinate. | 3,66 (1,18) | 0,43 | 0,18 |

| 2- Most bad thing I predict about myself come true. | 2,62 (0,97) | 0,42 | 0,17 |

| 3- I see myself as a useless person. | 2,30 (1,19) | 0,74 | 0,55 |

| 4- I avoid big projects for fearing not being able to handle them. | 2,95 (1,27) | 0,64 | 0,41 |

| 5- Overall, I am happy with the person I have become.* | 3,48 (1,00) | -0,61 | 0,37 |

| 6- I am often frustrated with my attitudes. | 3,17 (1,07) | 0,61 | 0,37 |

| 7- I am not good at accepting compliments. | 3,01 (1,24) | 0,40 | 0,16 |

| 8- I am able to plan for the long term* | 3,33 (1,19) | -0,37 | 0,14 |

| 9- I would like to be a better person. | 4,22 (0,89) | 0,41 | 0,17 |

| 10- I trust my own decisions.* | 3,20 (0,93) | -0,56 | 0,31 |

| 11- I believe I deserve life’s struggles. | 2,90 (1,08) | 0,30 | 0,09 |

| 12- I mostly make jokes about myself. | 3,47 (1,22) | 0,31 | 0,09 |

| 13- I have more flaws than most people. | 2,50 (1,03) | 0,64 | 0,41 |

| 14- My relationships always end because of me. | 2,38 (1,12) | 0,59 | 0,34 |

| 15- I’m unable to see any possibilities to achieve my goals. | 2,06 (1,02) | 0,60 | 0,36 |

Note: * = Reverse Item.

3.1. Partial Discussion

The self-deprecation scale showed psychometric indices that indicated its validity and reliability according to the field’s previous literature (Filho & Júnior, 2010). Its unifactorial organization remained consistent in the analyses, reflecting one of the possibilities for attitudinal measures (Hernandez-Ramos et al., 2014): Despite cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects being considered, factor analysis does not necessarily distinguish the three components, thus justifying the existence of a single factor (Masuri et al., 2016; Neiva & Mauro, 2011).

Even taking into account the possibility of this factor organization, it was still necessary to empirically compare a one-factor versus a three-factor model. Thus, to better understand this factorial structure, as well as observe the adequacy indexes of the proposed model and analyze the discriminant validity using previously developed scales, a second study was necessary.

3.2. Study 2: Confirmation of the Factor Structure, Calibration and Correlates

3.2.1. Participants

The survey included 200 volunteers from the general population, mostly female (65 %), students (74 %), single (55,5 %), and middle-class members (50,5 %). The average respondent’s age was 21,8 years (SD = 5,69) with a higher frequency of 19 years old (21,5 %) and an age range between 18-52. Again, a convenience sample was utilized.

3.2.2. Instruments

In addition to the Self-Deprecation Scale and the sociodemographic questionnaire, the following instruments were used.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. A scale developed by Rosenberg (1989) and adapted to the Brazilian context by Hutz and Zanon (2011). The measure consists of 10 items answered on a 4-point scale, which measure the individuals’ global self-esteem. Its reliability in the present study was α = 0,89.

Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale. An instrument that measures self-esteem with a single Likert-type item (“I have high self-esteem”). It was created and validated by Robins et al. (2001) and adapted in Brazilian Portuguese by Pimentel et al. (2018).

Single-Item Narcissism Scale. Developed by Konrath et al. (2014), it is a single item measuring narcissism. The participant is asked to demonstrate his agreement with the statement “I am a narcissist”, using a seven-points scale.

Aggression Questionnaire. Instrument that measures four dimensions of dispositional aggression: physical aggression (α = 0,74), verbal aggression (α= 0,58), anger (α = 0,81) and hostility (α = 0,70), through 26 items answered in a Likert scale. It was developed by Buss and Perry (1992) and validated in Brazil by Gouveia et al. (2008).

3.3. Procedures

Data collection was performed similarly to the previous study, both in person and online. The participants took an average of 20 minutes to complete all scales and the sociodemographic questionnaire. Brazilian ethical guide- lines regarding research with human beings were once again followed (e.g. informed consent).

3.4. Data Analysis

The R language was used. Initially, refinement analyzes were performed using the Item Response Theory as a basis, through the graduated response model, based on inclination (the ability of an item to demonstrate small changes in the latent trait, where the cutoff point is 0,6) and position (which registers the levels of the latent trait necessary to answer an option on the response scale) (Primi, 2004). The mirt package (Chalmers, 2012) was chosen for this phase of the analysis. After this step, the confirmatory factor analysis was continued.

To this end, the following adjustment estimators were observed, using the Maximum-Likelihood (ML) estimator and based on the described criteria: the χ2/gl, where values under 3,0 are the ideal; the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), the Incremental Fit Index (IFI), the Comparative Fit-Index (CFI) and the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) (both have a cut-off point above 0,90 for good indicators); the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (where values up to 0,08 are considered); and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), which accepts values up to 0,10 as an indication of good fit (Byrne, 2012; Kline, 2016). To calculate the estimators, we used the lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) and semPlot (Epskamp & Stuber, 2017) packages.

In addition to the model fit itself, analyzes were carried out to characterize the sample, to observe reliability, and to observe relations between self-dep recation and the previously mentioned scales. For that, descriptive analyzes, McDonald’s Omega, Cronbach’s Alpha and Spearman’s correlation were used. This correlation method was used specifically because the aggressiveness sub-factors (except, hostility), and the single-item measures did not show a normal distribution.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Calibration

Initially, the scale was calibrated. The scores for inclination (a) and position (b) can be seen in Table 2, and indicated the exclusion of items 1, 11 and 12, as they did not reach the cutoff point for inclination.

Table 2 Inclination (a) and Position Parameters (b)

| Items | Item Mean (DP) | a | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1- I tend to procrastinate. | 3.66 (1.18) | 0.50 | -5.61 | -3.30 | -1.29 | 2.39 |

| 2- Most bad thing I predict about myself come true. | 2.62 (0.97) | 1.36 | -1.71 | 0.14 | 2.14 | 3.28 |

| 3- I see myself as a useless person. | 2.31 (1.19) | 3.64 | -0.31 | 0.59 | 1.17 | 1.93 |

| 4- I avoid big projects for fearing not being able to handle them. | 2.96 (1.27) | 1.47 | -1.35 | -0.26 | 0.65 | 2.10 |

| 5- Overall, I am happy with the person I have become.* | 2.52 (1.00) | -1.43 | 3.10 | 1.58 | 0.42 | -1.51 |

| 6- I am often frustrated with my attitudes. | 3.17 (1.07) | 1.64 | -1.90 | -0.55 | 0.55 | 2.06 |

| 7- I am not good at accepting compliments. | 3.01 (1.24) | 1.27 | -1.42 | -0.16 | 0.68 | 1.97 |

| 8- I am able to plan for the long term* | 2.67 (1.19) | -0.75 | 3.97 | 2.26 | 0.45 | -2.52 |

| 9- I would like to be a better person. | 4.22 (0.89) | 0.83 | -5.01 | -3.82 | -2.09 | 0.44 |

| 10- I trust my own decisions.* | 2.80 (0.93) | -1.67 | 2.94 | 1.21 | -0.18 | -1.83 |

| 11- I believe I deserve life's struggles. | 2.90 (1.08) | 0.30 | -6.52 | -2.85 | 4.07 | 9.53 |

| 12- I mostly make jokes about myself. | 3.47 (1.22) | 0.18 | -12.49 | -4.70 | -0.54 | 8.79 |

| 13- I have more flaws than most people. | 2.50 (1.03) | 1.48 | -1.14 | 0.37 | 1.70 | 2.75 |

| 14- My relationships always end because of me. | 2.39 (1.12) | 0.87 | -1.15 | 0.40 | 2.58 | 4.19 |

| 15- I'm unable to see any possibilities to achieve my goals. | 2.06 (1.02) | 1.87 | -0.29 | 1.17 | 2.50 | 3.36 |

Note: * = Reverse Item.

4.2. Confirmatory Analysis

Considering the previous results, three models were tested: The first model contained the 12 items presented as adequate in the calibration, organized on a one-factor structure. The second model, also having one factor, contained the 15 items initially developed. Finally, the third model differed from the second by testing a three-factor organization, dividing the items between affective (3, 5, 6, 9 and 13), cognitive (2, 8, 10, 11, 14, 15), and behavioral (1, 4, 7, 12) aspects. The detailed results are presented in Table 3.

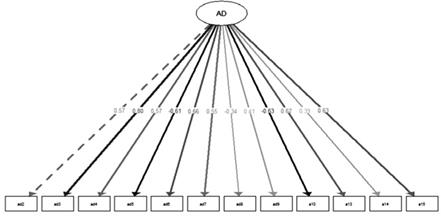

The single-factor 12 items model obtained the best model fit indices: χ2/df = 1,63; GFI = 0,93; IFI = 0,95; CFI = 0,97; TLI = 0,97; RMSEA = 0,04 (confidence interval between 0,01 - 0,08); and SRMR = 0,05. This organization obtained a reliability score of 0,85 (both in McDonald’s Omega and Cronbach’s Alpha, and can be seen in Figure 2.

Table 3 Model Fit Analysis comparison

| MODEL | Χ2/DF | GFI | IFI | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (CI 90 %) | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 Items, One-factor | 1,63 | 0,93 | 0,95 | 0,97 | 0,97 | 0,04 (0,01- 0,08) | 0,05 |

| 15 Items, One-factor | 1,69 | 0,90 | 0,91 | 0,91 | 0,89 | 0,06 (0,04- 0,08) | 0,06 |

| 15 Items, Three Factors | 1,74 | 0,90 | 0,90 | 0,90 | 0,88 | 0,06 (0,04- 0,07) | 0,06 |

4.3. Correlations

Finally, the self-deprecation scale was correlated with other psychological constructs, in order to observe the convergent validity. The data shown in Table 4 show that the strongest relationships were those with self-esteem and hostility, although correlations with all factors of aggressiveness were demonstrated.

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

| MEAN | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.SDe | 2,70 | 0,62 | - | |||||||

| 2.SE S | 2,82 | 0,60 | -0,75** | - | ||||||

| 3.SE I | 3,81 | 1,69 | -0,68** | 0,70** | - | |||||

| 4.NA | 2,90 | 1,51 | -0,06 | 0,13 | 0,29** | - | ||||

| 5.AG | 2,53 | 0,60 | 0,35** | -0,28** | -0,17* | 0,22** | - | |||

| 6.PA | 1,87 | 0,66 | 0,17** | -0,09 | -0,03 | 0,21** | 0,75** | - | ||

| 7.VA | 2,76 | 0,74 | 0,21** | -0,09 | -0,07 | 0,21** | 0,68** | 0,40** | - | |

| 8.AN | 2,67 | 0,97 | 0,29** | -0,25** | -0,14* | 0,21** | 0,85** | 0,58** | 0,50** | - |

| 9.HO | 2,95 | 0,80 | 0,39** | -0,35** | -0,23** | 0,11 | 0,74** | 0,37** | 0,41** | 0,49** |

*p < 0,05; **p < 0,01; SDe = Self-deprecation; SE S = Self-esteem Scale; SE I = Self-esteem Item; NA = Narcissism; AG = Aggressiveness; PA = Physical Aggression; VA = Verbal Aggression; AN = Anger; HO = Hostility.

4.4. Partial Discussion

Initially dealing with the model fit analyzes, the obtained values are considered satisfactory according to the literature (Byrne, 2012; Kline, 2016). Items 3 (‘’I see myself as a useless person.’’), 5 (‘’Overall, I am happy with the person I have become.’’), 6 (‘’I am often frustrated with my attitudes.’’), 10 (‘’I trust my own decisions.’’), and 15 (‘’I’m unable to see any possibilities to achieve my goals’’) as those who obtained the best results, considering both studies. This organization can be taken into account by future studies that wish to validate a shorter version of the scale.

The inclination criteria indicated the removal of three items. Items 1 (‘’I tend to procrastinate’’), 11 (‘’I believe I deserve life’s struggles’’) and 12 (‘’I mostly make jokes about myself’’), showing that they were unable to demonstrate differences in the latent trait’s representation (Couto & Primi, 2011). It is relevant to point out that of the three items, two describe behaviors, going according to the difficulty in representing behavioral aspects in self-reported attitude measures (Neiva & Mauro, 2011).

The single-factor organization once again was the most psychometrically adequate, corroborating Study 1’s results. Discussing the measurement of psychological objects, Pasquali (2007) describes them as being composed of several sublevels, or sub-systems. Thus, despite the construct of self-deprecation being composed of cognitive, affective and behavioral sub-systems (as evidenced by the psychometric indices presented by the scale), the instrument developed in the present research measures the system in general.

Regarding convergent validity, defined by Pasquali (2007) as when the instrument has a significant correlation with another test that measures a theoretically related trait, the Self-Deprecation Scale also obtained satisfactory results. Although the literature on this topic is scarce, its relationship with self-esteem (Owens, 1994) was maintained, even using two different scales to measure this construct. Thus, the results presented indicate that the measure is valid for future use. The result of the reliability test also reinforces this statement, with the score being considered significant (Valentini & Damásio, 2016).

4.5. General Discussion

The present research aimed to develop and validate an instrument that measures self-deprecation, also analyzing its relationship with other psycho- social aspects. These objectives were met, with the Self-Deprecation Scale having 12 items that measure the construct validly and reliably, also showing correlations with other psychological constructs.

A strong negative correlation was shown between the Self-deprecation Scale and both self-esteem instruments used in the research (-0,75 with the scale and -0,68 with the single item). Thus, although the two phenomena are correlated, self-deprecation relies on behavioral and cognitive aspects (e.g., self-fulfilling prophecies and difficulties in long-term planning) that are not present in self-esteem. Therefore, although Owens (1994) is correct in differentiating the two constructs, the results reported here show that this disparity goes far beyond two faces of the same psychological dimension. It is possible to theorize that self-deprecation is a consequence of low self-esteem, not its representation: that is, the development of a negative attitude towards oneself generated by a decrease in self-esteem (Neenan & Dryden, 2006). Future studies can further investigate this idea.

The negative correlation with self-esteem also corroborates the results that were presented by Huprich and Nelson (2014) concerning malignant self-regard and by Szcześniak et al. (2021) regarding the self-presentation aspect of self-deprecation. Future studies can investigate the relations between these three measures, aiming to provide more information about these constructs and their similarities.

On the other hand, self-deprecation had a positive correlation to all aggression dimensions, especially anger (ρ = 0,29, p < 0,01) and hostility (ρ = 0,39, p < 0,01). This information is in line with previous research, which points out that a negative view of oneself is related to aggression, especially its covert dimension (anger and hostility) (Bradshaw & Hazan, 2006; Teng et al., 2015). Future studies may provide further evidence for the existence of this relationship, helping to understand the inconclusive results about the impact of self-esteem on aggressive behavior, being relevant to understand this relationship (Barry et al., 2018).

But what would lead to the self-deprecation - aggressivity relationship? A hypothesis is that individuals who see themselves negatively and who suffer from self-deprecation consequences (e.g., difficulties in professional life and relationships) would be more aggressive as a way to avoid focusing on the negative feelings associated with these failures (Teng et al., 2015; Zapf & Einarsen, 2011). From a clinical perspective, covert aggression is a defense mechanism for those with a negative self-perception: The individual views himself negatively and projects this view onto others, and reacting aggressively shifts the focus from self-depreciation to reacting to the social inter- action (Shanahan et al., 2011).

This assumption is supported by the review carried out by Dutton and Karakanta (2013), where depressive symptoms were shown to be one of the risk factors for aggressive behaviors. Besides that, the authors add that the affective state caused by self-deprecation can lead to confusion in the attribution of external and internal causes to negative events, thus contributing to aggressiveness. Considering this relationship between self-deprecation and depressive symptoms (VandenBos, 2010; Kim et al., 2021), the presence of greater aggressiveness in individuals who self-depreciate can follow the same path. However, studies that clarify aspects of depression that are more clearly related to self-deprecation are necessary for this argument to have more empirical support.

Finally, there was no significant relationship between self-deprecation and narcissism, which can serve as evidence of the difference between this construct and self-esteem, which exhibits a well-known correlation with said personality trait (e.g. Crowe et al., 2018). On the other hand, these data may have been influenced by the use of a single item to measure narcissism. The description of this item discusses what briefly characterizes a narcissistic person and focused on the negative aspects, which may have skewed the responses due to social desirability. Thus, the use of a more comprehensive instrument may be necessary to observe the relationship between self-deprecation and narcissism.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Despite the aims being fulfilled, no study is free of limitations. In this research, the biggest restraint was the sample. Since the sample was non-probabilistic and by convenience, there was a considerable disparity between the groups, especially concerning gender (the vast majority of participants are women), age, and employment status (there were considerably more volunteers who were students). In addition, this type of sampling, although more accessible, reduces the possibility of generalizing the results, even considering the statistically significant results. Thus, further research using this instrument can apply it with different populations, to observe whether its psychometric properties are maintained.

On the other hand, it is possible to state that this research has made significant contributions to psychological science. Not only was the concept of self-deprecation addressed systematically and as the main focus, but from this theoretical construction came a valid and reliable measure, as shown by the two studies’ results. The self-deprecation scale demonstrated relationships with constructs addressed by Psychology for decades, such as self-esteem and aggression. The relationship with trait aggressiveness, in special, can be used in further studies to investigate the depression-aggression link (Dutton & Karakanta, 2013), for example, considering a moderating role of self-deprecation.

As a concept in its initial stage of development, the possibilities for other future research are numerous: testing the validity and reliability of the Self-Deprecation Scale with samples different from those used in the two studies, for example, can indicate the extent to which this is an adequate and comprehensive measure. Expanding the measure, especially concerning the behavioral intention items, can also help to understand this psycho-logical object, as well as the development of scales that exclusively address cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects.

The way we perceive ourselves in our environment has far more consequences than one might initially think. We analyze and understand social reality using ourselves as a starting point, and for this reason, it is relevant to devote more attention to the said observer. The present study presents a solid start for the further investigation of self-deprecation, and of all the issues that may be related to it.