INTRODUCTION

In the end of 2019, the planet was faced with a pandemic of the disease covid-19, generated by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which had its first record in China and, quickly, spread to different countries around the world (Qiu et al, 2020, Parasher, 2021), causing a high number of infections and deaths (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020a). For this reason, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency of international importance and classified it as a pandemic on march 11, 2020 (Lana et al., 2020).

In Brazil, the first official case of a person infected with covid-19 occurred on February 26, 2020 and quickly reached the entire country, creating a wave of illness and death (Ferreira et al. 2021; Ferreira et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2023; Oliveira et al., 2020). After more than two years of pandemic, in the beginning of 2022, there were more than 23 million confirmed cases, 622 thousand deaths in the different brazilian states (WHO, 2020a) and people live with a certainty of a return of a new wave of growth, throughout the country, with the hope of another decrease in records with the advancement of vaccination in the country.

The contamination by the new coronavirus can occur through direct contact with the virus transported by air, through droplets of saliva, sneezing, coughing and phlegm. The most common symptoms of the disease include fever, cough, fatigue, respiratory distress, muscle pain (Carfì et al., 2020), which can arise in a mild to severe way or be completely absent, as in the case of asymptomatic patients. In this sense, it is important to emphasize that, in pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic cases, in which the symptoms have not manifested, the viral load of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is still capable of being transmitted in the same way as those in which the symptoms are already present (Aquino et al., 2020, Melo et al., 2021; Parasher, 2021).

Due to the high power of transmission of the virus in its different forms, the detection of cases that can only be confirmed through laboratory tests, the non-availability of the vaccine for everyone and the risk of exhaustion of health services, as a way of preventing mass contamination, WHO recommended compliance with physical contact and movement restrictions to control the disease (Kraemer et al, 2020). Thus, national and international authorities have taken these preventive measures according to the severity of the situation in the different countries affected by the pandemic, with the aim of slowing the spread of the virus and reducing the demand for the services of the public and private health system in the care of severe covid-19 cases (WHO, 2020b).

In addition to the hygiene recommendations and the use of masks to avoid contagion, different measures were also established in order to guarantee physical distance between people and, thus, slow down the contagion. These measures to restrict social contact happen through social distancing, intended to prevent the population from having close physical contact; and social isolation and quarantine, in which, respectively, those infected or suspected of having the disease must remain isolated so they won’t transmit the disease to others. Stricter measures, such as the lockdown, were also established by the authorities to prevent the displacement of people, through the complete suspension of their movement, being allowed only the work of services considered essential (Aquino et al., 2020; Ferreira et al. 2021; Ferreira et al., 2022; Hildebrandt et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2020).

In this context, the measures imposed to prevent the disease did not necessarily mean absolute social isolation, but they brought significant consequences with regard to one of the essences of the human being: its condition as a social being who, after going through initial biological stages, become insert into society through communication and established social laws (Leontiev, 2004). From this, it is possible to perceive that the long-term stay at home, with a lack of this face-to-face socialization, can trigger significant changes, even among the youngest (Ivatiuk et al., 2022; Strömmer et al., 2022), a fact that brings psychosocial transformations for this age group, with the loss of contact between peers and the opportunity to experience socialization (Zhao et al., 2020, Melo & Soares, 2020).

Among the changes necessary for the temporary adaptation in the way of relating during covid-19, one cannot fail to mention the use of electronic media and digital technologies (Marciano et al., 2022). People of all age groups began to use them more frequently, for leisure, work and study, among other purposes. Technology, in this pandemic period, stands out as a basic tool that marks the current historical development, configuring itself as the main instrument of socialization, communication and work and study activities (Marciano et al., 2022), as can be seen in the remote activities carried out in the household (Ferreira et al. 2021; Ferreira et al., 2022; Pajarianto et al., 2020).

The technological revolution, marked by the accelerated flow of information (Santos, 1991), has been generating new configurations in personal relationships for decades. Information goes beyond the limits of time and space, facilitating communication and increasing the network of contacts in a shorter time and over greater distances, without people needing to have any physical interaction (Souza, 2004).

For the young population, this socialization process is an important factor through which they relate to the world in different ways for their identity construction (Souza, 2004). That said, despite the benefit of technology for social interaction (Shah et al., 2020), personal contact and interaction with different people -beyond the virtual means used for communication- have an essential role as a way of individual constitution and belonging to groups, in a way which the human being modifies and is modified when in contact with the world, being the psychic functioning mediated by social relationships (Oliveira, 1997). In the current pandemic context, these are hampered by the need for social distancing and possible reduction of contact and deeper social interactions (Shah et al., 2020, Marciano et al., 2022).

In this scenario, with the epidemiological, health, social and economic crisis, many negative psychological effects could already be observed in this period, such as symptoms of post-traumatic stress, anxiety, insomnia, irritability, depression, fear, among others (Brooks et al, 2020; Ivatiuk et al., 2022; Zwielewski et al., 2020), with some of these symptoms also being seen in children and adolescents (Branquinho et al., 2020, Meade, 2021). Added to this, there are problems inherent to the youth, related to the challenges of entering adulthood, which can be aggravated and generate mental illness (Orben et al., 2020).

The transition to adulthood, experienced by young people, characterizes a time of uncertainty, involving different changes in a person’s life, with the requirement of adjustment to the behavioral models of contemporary society (Nunes & Weller, 2006; Souza, 2004), preparation to enter the job market, the accelerated pace due to the demands of greater productivity and the expectation of leaving the parents’ house (Trancoso & Oliveira, 2014), situations that may generate greater anxiety at this time.

In addition, work has an important meaning in the capitalist conjuncture, representing the individual’s recognition before society. Thus, the absence of a job becomes a reason for great personal and collective stress and concern (Dutra-Thomé & Koller, 2014). This moment of passage experienced by young people might present even more challenges during the pandemic, due to the impact on the economy caused by the closure of non-essential services and the consequent increase in the unemployment rate (Churchill, 2021), bringing doubts about the future and suffering for these young people (Achdut & Refaeli, 2020), especially due to the unpredictability of economic instability (O’Keeffe et al., 2022).

However, despite the current and future negative consequences of the covid-19 pandemic for the world population, resignifications can also be observed in periods that require abrupt changes, demonstrating that most people are able to adapt, developing greater resilience in the face of changes and even create new life resignifications (Gao et al., 2020; Melo et al., 2021), including the young people (Branquinho et al., 2020, Strömmer et al., 2022). This resignification derives from the human being’s ability to interpret and transform the objective reality of facts into subjective meanings, thoughts and ideas, and modify human behaviors based on the social needs of each moment (Martins, 2011). Social adjustment and assimilation of new collective rules (Nunes & Weller, 2006) represent an important stage in young people’s lives, in which the development of their different identities, through confrontation and flexibility in the face of subjective and objective experiences (Takeuti, 2012), allow them to build paths and resignify the reality in which they are inserted, being able to generate new relationships, responses and meanings (Stamato, 2008) that are more adapted to deal with moments of crisis like this.

Supported by Vygotsky’s socio-historical perspective, that man is a historical being, built in dialectical relationships with society (Oliveira, 1997), it is understood that, in order to understand how the isolation measures experienced in covid-19 affect the individuals, it is necessary to focus on the thinking about the characteristics of our society, as well as the way these individuals present themselves nowadays. However, it is known that, depending on the age group, social behaviors specific to a particular group are identified and, equally, the social restriction experienced during the pandemic can affect each group differently. With these premises in mind, the present study aimed to identify the meanings that young people attribute to covid-19 social isolation measures. Such a cut is justified because in this period of development the demands for social interaction are intense, as it is a period that embraces the completion of the process of identity construction. Therefore, the way young people assimilate and experience the social demands of isolation has important specificities to be debated.

METHOD

Research Design

The study is configured in a descriptive, exploratory, survey and multimethod approach. Through the methodologies used, it was possible to verify and understand the meanings attributed to the experience of social isolation by young Brazilians, using direct questioning to them.

Instruments

Two instruments were answered to achieve the research objective. First, the participants answered a sociodemographic questionnaire, addressing factors such as age, sex, income, employment relationship, education, adherence to social isolation/distancing measures and country region. Then, they answered to the Free Word Association Method (FWAM) with the following instruction:

“What are the first 5 words that come to your mind when you hear the word “QUARANTINE?”. The choice for the term quarantine was because this is the way most Brazilians understand the contact restriction measures to prevent covid-19 (quarantine, distancing and social isolation).

Sample

Through a non-probabilistic convenience sample, at the end of the collection, it was possible to count on 571 young people. As inclusion criteria, it was considered: Brazilian participants, aged between 18 and 25. People without internet access and/or illiterate people unable to read did not participate in the research.

Participants had an average age of 21,55 years (SD = 3,02). Most were female (n = 438; 76,70 %), with no income (n = 187; 32,70 %), without work occupation (n = 313; 54,80 %), with incomplete higher education/university students (n = 316; 55,30 %), who were in voluntary social isolation (n = 485; 84,90 %), and lived in the Northeast region of the country (n = 310; 54,30 %).

Collection procedures and ethical aspects

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee under report No. 4,014,996, and respected all research ethical aspects with human beings indicated in the Resolution No. 466/12 of the National Health Council. For data collection, the instruments used were submitted on an online questionnaire platform, being added together with the Free and Informed Consent Term - IC. Data collection took place over 40 days, during a period when the country was experiencing strict social isolation in most cities. The disclosure took place through social networks (Facebook and Instagram), newspaper reports and digital portals. Participants who had access to the questionnaire could answer it anonymously and freely.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed in two stages. In the first stage, sociodemographic data was collected through descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage and measures of central tendency and dispersion), through the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), version 25.

In the second stage, the analysis of the FWAM was performed, with the support of the software Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (IRaMuTeQ). The software’s main objective is to analyze the structure and organization of discourse, making it possible to inform the relationships between the lexical worlds that are most frequently stated by the research participants (Camargo & Justo, 2013). Three textual analyzes were performed.

First, a Word Cloud was obtained, in order to group the words and organize them graphically according to their relevance, the largest being those that had the highest frequency, considering words with a frequency equal to or greater than 10. Then, classical lexicographic analyzes were extracted and used to verify statistics on the number of evocations and forms and text segments (TS). Finally, the Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC) was performed to recognize the dendrogram with the categories that emerged, and the higher the χ2, the more associated the word is with the category, and disregarding the words with χ2 < 3 0,80 (p < 0,05). For better use, the default settings were changed: size of RST1 (07), size of RST2 (05), number of terminal categories in phase 1 (07), minimum frequency of text segments per category (0), maximum number of analyzed forms (1200).

RESULTS

Word cloud

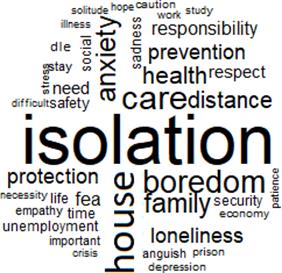

Initially, the word cloud generated from the participants’ evocations was obtained, verifying that the most representative were: “Isolation” (f = 220), “House” (f = 124); “Care” (f = 94); “Boredom” (f = 87); “Anxiety” (f = 75); “Family” (f = 70); “Health” (f = 60) (see Figure 1).

Classical Lexicographical Analysis and Descending Hierarchical Classification

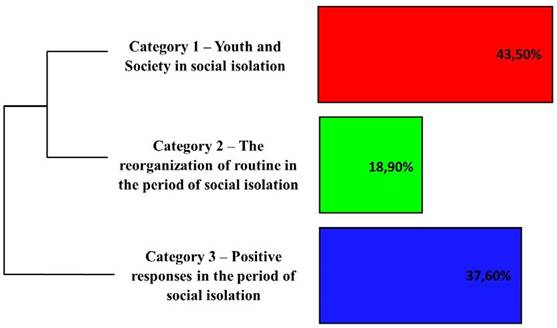

To understand the meanings given by the participants to the quarantine experience, a corpus consisting of 571 text segments (TS) was generated, with use of 492 TSs (86,16 %). 3,282 occurrences (words, forms or words) emerged, with 778 distinct words and 458 with a single occurrence. The analyzed content was categorized into three classes and named from the evocations that emerged: Category 1 - Youth and society in social isolation, with 214 TS (43,50 %); Category 2 - The reorganization of the routine during the period of social isolation, with 93 TS (18,90 %); and Category 3 - Positive responses to the period of social isolation, with 185 TS (37,60 %) (see Figure 2).

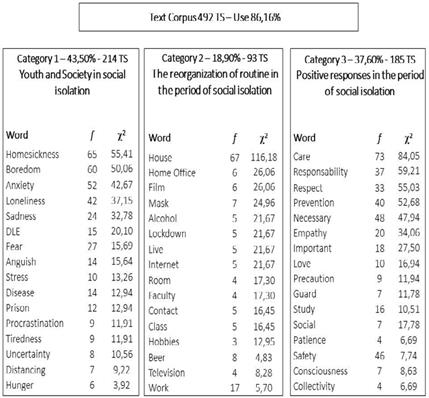

For a better visualization, a category diagram was elaborated with the list of words of each category generated from the chi-square test (χ2). In it, the evocations that presented similar vocabulary among themselves and different vocabulary from the other categories emerged (see Figure 3). Next, the categories that emerged from the descending hierarchical classification are described and exemplified.

Category 1 Youth and society in social isolation.

Category 1 - Youth and society in social isolation - comprises 43,50 % (f = 214 TS) of the total corpus studied. It presents words and radicals in the interval between χ² = 3,92 (Anger) and χ² = 55,41 (Homesickness). Words such as “Homesickness” (χ² = 55,41) and “Boredom” (χ² = 50,06); “Anxiety” (χ² = 42,67); “Loneliness” (χ² = 37,15); “Sadness” (χ² = 32,78); “DLE” (χ² = 15,69); “Fear” (χ² = 15,69); “Stress” (χ² = 13,26); “Prison” (χ² = 12,94) and “Tiredness” (χ² = 11,91) (see Figure 3) belong to this category.

Category 2 The reorganization of routine in the period of social isolation.

Category 2 - The reorganization of the routine in the period of social isolation -comprises 18,90 % (f = 93 TS) of the total corpus analyzed. It is formed by words and radicals in the interval between χ² = 4,49 (Coronavirus) and χ² = 116,18 (House). The category is composed of words like “House” (χ² = 116,18); “Home Office” (χ² = 26,06); “Film” (χ² = 26,06); “Mask” (χ² = 24,96); “Alcohol” (χ² = 21,67); “Lockdown” (χ² = 21,67); “Live” (χ² = 21,67); “Internet” (χ² = 21,67) and “Faculty” (χ² = 17,03) (see Figure 3).

Category 3 Positive responses in the period of social isolation.

Category 3 - Positive responses in the period of social isolation - is responsible for 37,60 % (f = 185 TS) of the total corpus collected. It covers words and stems in the range between χ² = 3,87 (Save) and χ² = 84,05 (Care). This category is composed of words such as “Care” (χ² = 84,05); “Responsibility” (χ² = 59,21); “Respect” (χ² = 55,03); “Prevention” (χ² = 52,68); “Empathy” (χ² = 34,06); “Protection” (χ² = 21,99); “Love” (χ² = 16,94) and “Consciousness” (χ² = 11,94) (see Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

Analyzing the data presented, it is suggested, through this study, that the countless possibilities of social interaction through electronic media are not enough to meet the needs of personal contact of young people. Considering the meanings of category 1, it is worth mentioning the fact that young people cited words that demonstrated how such spatial restrictions of interaction arouse feelings such as anxiety, homesickness, isolation, loneliness and prison. The urgent need to discuss this phenomenon points to the demand to comprehend the contemporary youth in the social isolation context in covid-19.

Therefore, it must be recognized that the rapid advance of informational technologies in contemporary times has boosted several social transformations, so that, currently, it is understood that the idea of an industrial society has been replaced by the concept of an informational society. In this sense, the world began to be marked by new symbols, as well as by the multinationalization of companies and the flexibilization of borders, in the face of the different communication modalities over long distances (Santos, 1991).

In the face of these worldwide social changes, Santos (1991), a leading brazilian scholar, still in the 1990s, claimed to have fostered a conjuncture of global interconnection and interdependence. As a result, these new configurations, as Souza (2004) points out, also triggered changes in the perception of time and space, since new technologies allowed interaction and creation of contact networks with people and groups from different locations, redefining, therefore, the understanding of time, since communication became instantaneous and of space, as they occur in a fluid way even in distant spaces.

That said, it is evident that, even before the restrictions caused by the covid-19 pandemic, the linking processes through informational networks were already being progressively intensified in the face of the numerous contact possibilities that transposed the geographic space. However, it is recalled that the identity construction of this stage of development unfolds from various interactions, references and experiences, creating meanings to their experiences (Souza, 2004).

The plural experiences of adolescents have always been characteristic of this phase, watered by many desires and uncertainties that trigger the search for many experiences, which end up adding to the construction of the self. However, in recent years, especially in large urban centers, crossed by competitiveness and individualism, desires and uncertainties have been maximized, fostering anxiety. Usually, in these big cities, it is possible to see exaggeratedly anxious young people. After this contextualization, it should be evidenced that the feeling of anxiety was highlighted repeatedly by the research participants. Nunes and Weller (2006) discussed this by stating that the new behavior models triggered by mass culture confront traditional models, a context that is already a trigger to the individual’s uncertainties with himself/herself and with society.

It is highlighted that young people experience moments of uncertainty in their identity construction process, being impelled by society both to think about their professional choices and to start a life of financial productivity. Trancoso and Oliveira (2014), when discussing the contemporary challenges of youth, point out that “entering the world of work, experiencing a more stable relationship with another person, completing high school or higher education, leaving their parents’ house, are milestones that still identify the passage to the adult world” (p. 268). It is considered, therefore, that the absence of face-to-face/non-virtual socialization put them in the face of reflections about these uncertainties with more intensity. On this, Souza (2004) reflects on the uncertainties of a time added to the uncertainties triggered by the changes and challenges in this period of life.

It is understood that the different areas of young people’s lives -such as work, studies, leisure and friendships- tend to demand considerable investment of time and energy. This situation was abruptly interrupted with the need for distancing and stoppage of activities, causing a sudden change in demands, in a way that these participants’ time started to be filled with unusual remote activities, such as remote classes, without them knowing how to organize them. Thus, young people reported feelings that translate into difficulties in managing new and necessary challenges, such as boredom, tiredness and procrastination.

Faced with the absence of face-to-face social contacts and the anxieties intrinsic to the pandemic, feelings emerged that distance themselves from a social perspective aggregated to mental health, represented by words such as: stress, fear, sadness, anxiety, anguish and illness. The literature also presents information about the psychological impacts in emergency situations such as the one being experienced, highlighting symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression, alcohol abuse, dependent and avoidant behaviors, even after the traumatic event is over, which is why it is essential to formulate interventions that take these symptoms into account in the long term (Zwielewski et al., 2020).

It is considered relevant to reflect on the possible symptoms of mental illness that were expressed during the months of physical distancing and revealed in this research, in order to transcend the biomedical perspective on mental health, understanding the symptoms in their biopsychosocial dimension and translating them from the current situation. It is understood, therefore, that these feelings are possible responses to the moment of isolation that put these young people in front of new social challenges (Marciano et al., 2022, Meherali et al, 2021).

The period of social restriction has triggered several changes in social interactions constituted over the centuries (Orben et al., 2020). New meeting and communication formats were developed and/or intensified, like the digital connection (Marciano et al., 2022, Orben et al., 2020). In this sense, it is considered important to emphasize the postulate that “[...] man is a being of social nature, that everything that is human in him/her comes from his/ her life in society, within the culture created by humanity” (Leontiev, 2004, p. 279). It is understood that the process of differentiating the human from its animal antecedents is relevant to support this conception of the human being as a social being.

Thus, the stages of hominization are discussed, unveiled by Leontiev (2004), which unfold into three stages. The first consists of preparing the biological apparatus for necessary functions, such as communication. The second unfolds from the first creation of instruments through work, a stage in which the biological changes followed these social productions, making them intrinsically related. The third stage, in turn, considered as the emergence of modern man, is also known as the turning point, because it is the moment when man becomes independent of his biological changes and starts to be governed by socio-historical laws (Leontiev, 2004).

Throughout historical progress, society has been carrying out activities and transforming nature in order to meet its needs, developing houses, machines, clothes and other material goods that imply the process of subjectivation of social subjects, among them, it is important to highlight the necessary technologies, highlighted by the young research respondents regarding the practice of new forms of leisure, the use of new work instruments and access to university and schools and, as Leontiev (2004, p. 283) points out, “[...] all the progress in the refinement, for example, of working instruments can be considered, from this point of view, as marking a new stage of historical development [...]”.

With this, the theorists of the Historic-Cultural Psychology argue that as the human being transforms nature, he is also transformed by it. Oliveira (1997), therefore, understands three central ideas of Vygotsky as: a) the understanding that there is a biological basis for psychological functions, since these are the result of brain activity; b) The meaning that psychological functioning occurs from the social relations between the individual and the world, in a socio-historical process; and c) that this relationship is mediated by symbols (Oliveira, 1997).

In this circumstance, the understanding of youth is considered from a socially constructed process in a given historical, economic, political and cultural context, deviating from a naturalizing conception in order to access them, glimpsing the meanings that are created in the contradiction between the needs that young people have and the concrete possibilities of satisfaction within the capitalist society (Stamato, 2008). Therefore, Stamato (2008) delineates that “the extension of the school period, the distance from parents and family, the proximity of peer groups, generated the creation of a new social category with collective patterns of behavior youth/adolescence” (p. 134).

Young people commonly have a significant ability to adapt to new life situations, since the identity construction process implies openness, flexibility and apprehension. As Stamato (2008, p. 133) pointed out: “[...] youth is a privileged period of formation of higher psychological functions. A period in which the possibilities of establishing new connections and new relationships, of transformations of meanings and senses, are expanded”.

It is essential to emphasize, then, that this constitutive process of youth identity occurs in a multiple, complex, unprecedented and plural way. Therefore, the different youths have their identities built “[...] in processes of confrontation, opposition, domination, submission and resistance that occur in the symbolic and material plane of social relations. That is, they go through the articulation of subjective elements and various objective situations” (Takeuti, 2012, p. 432). In this aspect, it is understood that the process of reorganizing their daily lives, in the face of the restrictions imposed by the quarantine context, also required the mobilization of affectivity, as well as actions and confrontations in order to be able to produce the novelty and remodel their desires in their daily routine.

In face of the words that emerged, category 2 raises meanings that may be related to this reconstruction process in evidence for these young people, that indicated their new ways of having leisure, such as: movies, lives, internet, television, contact and hobbies, as well as words related to professional and academic life, such as: home office, work, college and class. These new configurations require the use of new instruments, or even the production of new meanings about them, since “The instrument is at the same time a social object in which historically elaborated work operations are incorporated and fixed” (Leontiev, 2004, p. 287). It happens that, with the incorporation of new operations and senses, a reorganization of natural movements unfolds, the formation of higher motor faculties and, consequently, the formation of new aptitudes and higher psychomotor functions.

It is known that one of the characteristics of youth is, precisely, the preparation time for affiliation to the world of work, in which, in general, is precarious. Work is considered a fundamental part of the individual, since it is through it that the subject uses and transforms instruments and signs, being modified by them concomitantly. However, in contemporary society, the concept of work has acquired recognition and social prestige contours, so that the lack of a work occupation leads to “psychosocial tension, both at an individual and community level” (Dutra-Thomé & Koller, 2014, p. 369).

Part of the young people undergo an extension of their training time for the world of work, remaining longer dependent on their families. This expansion of studies was also evidenced in this study, since most respondents declared themselves to be students and said they were not employed (Nunes & Weller, 2006; Souza, 2004).

From the perspective of Historic-Cultural psychology’s authors, it is understood that the psyche is seen as a material and ideal unit. It is defined, therefore, as a “subjective image of the objective world” (Martins, 2011). This unit is composed of several psychological functions, including sensation, perception, memory, thought, language, emotion and feeling, which operate in articulation and interdependence. The construction of “psychic images” is carried out by various living beings, but only humans begin to convert images into signs, a conversion that provided conditions for the development of language, as well as the construction of ideas. As Martins (2011) points out: “[...] in the development of psychological functions, there is a continuous overcoming transit that implies: capturing the real image sign word idea. Ideas manifest themselves as concepts and/or judgments” (p. 47).

It is highlighted that the concepts and judgments are based on sensory experience that, with language and rational operations, start being transformed into thought. Such rational operations are referred to as “analysis/ synthesis, comparison, generalization and abstraction” (Martins 2011, p. 47). The respondents exposed this phenomenon of judgment construction, sharing values and social norms. This occurs when objective experiences are subjectively signified and, therefore, internalized (Nunes & Weller, 2006).

It should be noted that many of the young respondents understand the importance of adapting to social norms, respecting rules, even when these are imposed abruptly and contrary to their life plans, demonstrating the adaptation of young people in understanding the importance of health standards for the current and future pandemics (Branquinho et al., 2020). The process of identity construction also implies adaptation to social life, leaving aside self-centered behaviors, as Stamato (2008) points out: “From the awareness of oneself and the awareness of the other, personal and social subjectivity interpenetrate. On the other hand, through concrete activity, the subject is included in objective reality and acts individually according to social demand” (p. 177).

Influenced by Spinoza’s philosophy, Vygotsky also spoke about affectivity, considering it in order to break with a cartesian dualistic understanding that separates emotion and reason. The authors of this perspective, in fact, consider that these spheres are intrinsically articulated. Martins & Carvalho (2016), when unraveling Leontiev’s understanding of this theme, consent with this understanding by stating that “The same subject-object relationship that promotes the construction of motives, which gives objectivity to the need and raises emotional experiences, occurs on a dynamic psychological background” (p. 705).

Emotions and feelings have different nature. Emotions start from an immediate sensory experience from the contact with concrete reality and are related to physiological manifestations, producing bodily sensations that influence muscle tone. Feelings, in turn, are mediated by cultural aspects and exposed through language, giving meaning to what is experienced (Martins & Carvalho, 2016).

In face of the explanations about the affective dimension, category 3 suggests that the young respondents tried to adapt and reorganize themselves in order to constitute purposes and meanings in the face of the adversities that emerged in the context of the quarantine as a result of covid-19. Words like love and patience, therefore, were chosen as a representation of their affections and elaborations in face of the whole context in which they are situated. It was identified, throughout the analyses, that young people cited words that translate feelings related to a thought of both self-protection and the collective, such as responsibility, collectivity, respect, protection, safety, care, awareness, precaution and prevention. About this social conscience, Stamato (2008) will point out that it generates self-awareness, building conceptions about themselves and socially differentiating themselves and that this promotes an impact on their subjectivation and on their way of acting in the world.

Finally, it is understood that the flexibility of young people in the face of novelties became evident throughout the responses. The influences of the reflexes of the contemporary informational society are highlighted, which unfold values such as innovation and flexibility in the face of social transformations.

CONCLUSION

It was possible to verify, through this study, the meanings that young people attribute to isolation measures during the covid-19 pandemic in Brazil. First, it is observed that, although they are already inserted in the computerized context resulting from the current technological revolution, maintaining only virtual communication, through digital media, is insufficient to meet the needs in the social relations of this group. These changes in social contact, exclusively or primarily virtual due to the demands of isolation measures in the pandemic, reflect on feelings of loneliness, anxiety, homesickness, and might result in harmful consequences for the mental health of young people.

Also, in order to comply with the measures established to contain the virus, the young people pointed out the changes that occurred in their routine, with the need to remain at home, assuming work and study activities in this place, remotely, and modifying their leisure time to more individual ways at home, as well as acquiring new hygiene behaviors. On the other hand, from these transformations, it was also possible to perceive the flexibility of these young people in the face of the serious health crisis and resignification through the new social needs presented, reflecting in a speech of greater awareness and collective responsibility.

LIMITATIONS

Like any scientific endeavor, this research has limitations. Aspects related to the sampling characteristics and the collection procedure are highlighted here. The sample was mostly represented by women, from the Northeast and with higher education, which does not represent the general reality of the young Brazilian population. Online data collection is also a limiting factor, since it does not reach all social segments, as in the case of people without access to technological means or with reading limitations, although this collection method has been essential to reach participants from different regions and contexts in Brazil, especially in a scenario of social isolation. It is contemplated, however, that it is not the purpose of this study to generalize the results, but to explore this reality.

In this way, the importance of carrying out studies on the subject with more representative samples in different regions of the country is highlighted, with the aim of offering reliable scientific data to the population and government authorities, contributing to the formulation of more targeted social interventions and actions in this context of health and humanitarian crisis.

HIGHLIGHTS

The repercussions of the covid-19 pandemic context on the lives of young Brazilians are investigated. Young people listed the meaning of social isolation in their lives, where associations were found between social isolation and negative feelings, highlighting the need for a non-virtualized interaction in their relationships, as well as receiving a change in their routines due to the blockade. In addition, this period was related to a maturation and affective responsibility in the face of the gravity of the moment.