INTRODUCTION

Bullying is considered to be an abusive behavior that has undoubtedly a long history and is very persistent in the present world. Most of the educators care about their students but sometimes they might be having a bad but most of the time they are kind and caring towards their pupils. However almost everyone who has been a student has experienced mean teachers during his or her studies. In some cases educators’ mean and weird behavior is due his personality traits or it can also be a personality conflict between a teacher and a student. In other cases it can be related to work load, stress or a mismatch between a teachers teaching and students’ learning style and most of the time these mean and wicked behavior of teachers crosses the line which leads to bullying by Educators. Studies on bullying first started with primary education students in Scandinavian countries and continued with secondary education students. But measures of violence used by teachers are not limited to primary and secondary education only, Chapell et al. (2004) mentioned that studies on bullying are common in primary and secondary education while they are quite rare in higher education. On the other hand, violence is also observed in higher education but in a very different form. While physical violence is common in the first years of education, it rather manifests itself as emotional and physical violence in higher education. According to Turkel (2007), bullying is physical in primary education, which becomes relational in adolescence and turns into sexual bullying in adulthood. It is even observed in business life in the form of mobbing. Another limitation is that almost all of the studies in the literature have investigated studentto-student violence (Kondrasuk, Greene, Waggoner, Edwards and Nayak- Rhodes, 2005). However, violent and uncivil behaviors of faculty members are yet to be investigated further. On the other hand, Coleyshaw (2010) defined bullying as a “social phenomenon”, and mentioned that the insufficient number of bullying studies have attributed by the fact that university administrators do not conduct bullying research to preserve their own power backed by corporate policy, and do not explain the contemporary incidents of bullying and violence. Therefore, violence by faculty members has been ignored from time to time.

Effects of Violence on Students

For instance, it was stated in Sweden that maltreatment caused psychologically negative results on medical students, which led to anxiety, depression, insomnia and stomach aches; students also lost interest in academic matters and had a reduced effectiveness in studying (Larsson, Hensing & Allbeck, 2003). It was found in Chile that maltreatment by faculty members had negative impacts on medical students’ mental health, wellbeing, social lives, perceived occupational identity and many students thought about dropping out (Maida et al., 2003). In Egypt, students stated that faculty members had insensitive and indifferent attitudes, and they found it uncomfortable to get along with the faculty members (El-Gilany, Amr, Awadalla and El-Khawaga, 2008). It was observed in Japan that university students experienced reluctance, depression, loss of appetite and several health problems following various harassment incidents by the faculty members (Nagata-Kobayashi, Maeno, Yoshizu and Shimbo, 2009). Similarly, in a recent study, Rowland et al. (2010) stated that faculty member’ bullying caused students to use medication to reduce stress and led to depression and anxiety symptoms.

Prevalence

In a study performed by Chapell et al. (2004), 19 percent of the students reported that they were subjected to bullying by faculty members and 44 percent of the students reported that they witnessed other students being bullied. In some of the studies, it has been stated that there are culture-specific types of violence and behaviors and certain types of violence are more prevalent than others. For example, in the Netherlands, Rademakers, van den Muijsenbergh, Slappendel, Largo-Janssen and Borleffs (2008) defined their own culture as being “feminine” and stated that there is a sexually and socially egalitarian structure between genders and women are more assertive than they are in other cultures. On the other hand, Bronner, Pertz and Ehrenfeld (2003) stated in their study that in Israel, Israeli men do not count sexual jokes as sexual harassment but as part of a normal and friendly talk between women and men, and it is impossible to find that the actual prevalence of victims from sexual harassment are shy to mention or reporting about it. Nagata-Kobayashi, et al. (2009) stated that compelling someone to take alcohol is common in Japan and identified “alcohol-related” harassment to be a Japanese culture-specific type of harassment and reported that it is the second most prevalent type of harassment (51,8 %) in higher education. It has been also frequently mentioned in American literature that alcohol leads to harassment incidents.

Continuance and Repetition of Violence

In a study, the participating students were asked about how they perceived uncivil faculty member behaviors and it was found that such bullying behaviors caused rage, anger, hindrance and powerlessness. Indeed, even the smallest things done by students easily tends faculty member to get angry and such situation leads to more tension between students and faculty members. In such cases, students avoid any sort of discussion with the faculty members and start giving up on their studies and avoid looking for solutions due to the fear of getting failed. Morrissette (2001) stated that “uncivil behaviors lead to uncivil behaviors” and it was found out by keenly observing the teachers of various students. Consequently, once a problem between a faculty member and a student is not solved, the faculty member starts to think about it negatively, which causes low self-esteem, depression and anger among faculty members. Thus, the faculty member makes minimum effort to do his/her job, waits for retirement and either changes jobs or quits the job (Thomas, 2003).

This study investigates how university students in Turkey are affected by violent and uncivil behaviors of faculty members and how they dealt with them formally and individually. It also aims to compare violent incidents with other countries and investigates the cultural differences in the occurrence of violence.

Answers to the following questions were sought in this research

Are students threatened with being graded low or failed?

How did the students, who were victims of bullying and uncivil behaviors, solve the incident formally or informally, from whom did they receive assistance, what were their attitudes toward it, to whom did they report it and how were such reports resulted?

Have you ever experienced a bullying incident or uncivil behavior that brought you into conflict with anyone?

How does being subjected to bullying and uncivil behaviors affect students individually and academically, and how do they cope with it?

Have the students seen other students being subjected to bullying and uncivil behaviors, and if so, what kind of behaviors have they witnessed?

Have the students bullied or showed uncivil behaviors toward a faculty member? If so, what kind of uncivil behaviors have they shown?

Why are students subjected to bullying and uncivil behaviors at universities? What are the characteristics of student victimization in different forms and why have they been subjected to such uncivil behaviors? What are the types of discriminative behaviors and attitudes that the students experience, and what are the possible causes of them?

What are the characteristics of the faculty members who commit the bullying and who use uncivil behaviors the most?

In which places does bullying incidents/uncivil behaviors occur the most?

What is the most observed type(s) of bullying in the Turkish higher education system? Is there any differences or similarities between them and other cultures?

METHODS AND APPROACHES

Instrument

The students were asked about the verbal, physical and social types of bullying that they had encountered during their university education. The questions were based on Olweus’s concept of bullying. The students were asked about various types of the verbal, physical and social violence that they had experienced during their four years of education. In addition to these three types, sexual and cyber violence were also examined as possible forms of bullying.

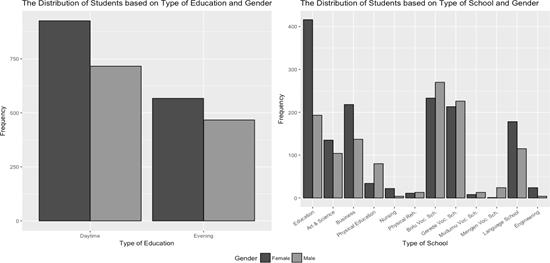

Participants: The subjects of this research were university students who attended a medium sized state universities in West Black Sea Region, in Turkey. Students who were receiving daytime and evening education at different faculties, colleges, vocational schools, and language preparatory schools in the last term of their education were selected for the study. There were 1493 (55,8 %) female and 1183 (44,2 %) male students who participated in the study. This number represents 15,46 percent of the total university population. Out of the total number of participants, 1642 (61,4 %) received daytime education while 1034 (38,6 %) received evening education. Data of students coming from several types of schools and date of female and male students are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Table 1 Participants’ Distribution According to the School Types and Gender

| Kind of Faculties & Schools | Daytime Education | Evening Education | Total Number of Female Students | Total Number of Male Students | Total Number of Students N | ||||||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | ||||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Education Faculty **** | 252 | 27.2 | 117 | 16.3 | 164 | 28.9 | 76 | 16.3 | 416 | 27.9 | 193 | 16.3 | 609 | 22.8 | |

| Business Faculty **** | 130 | 14 | 70 | 9.8 | 88 | 15.5 | 67 | 14.3 | 218 | 14.6 | 137 | 11.6 | 355 | 13.3 | |

| Arts and Letters Faculty **** | 107 | 11.6 | 77 | 10.8 | 28 | 4.9 | 27 | 5.8 | 135 | 9 | 104 | 8.8 | 239 | 8.9 | |

| Engineer. & Architecture Faculty **** | 24 | 2.6 | 4 | 0.6 | 24 | 1.6 | 4 | 0.3 | 28 | 1 | |||||

| Physical Education College**** | 34 | 3.7 | 80 | 11.2 | 34 | 2.3 | 80 | 6.8 | 114 | 4.3 | |||||

| Nursing College**** | 22 | 2.4 | 4 | 0.6 | 22 | 1.5 | 4 | 0.3 | 26 | 1 | |||||

| Physical Rehab. College**** | 11 | 1.2 | 13 | 1.8 | 11 | 0.7 | 13 | 1.1 | 24 | 0.9 | |||||

| Bolu Vocational School ** | 59 | 6.4 | 94 | 13.1 | 174 | 30.7 | 176 | 37.7 | 233 | 15.6 | 270 | 22.8 | 503 | 18.8 | |

| Gerede Vocational School ** | 154 | 16.5 | 147 | 20.5 | 59 | 10.4 | 79 | 16.9 | 213 | 14.3 | 226 | 19.1 | 439 | 16.4 | |

| Mengen Vocational School ** | 1 | 0.1 | 24 | 3.4 | 1 | 0.1 | 24 | 2 | 25 | 0.9 | |||||

| Mudurnu Vocational School ** | 8 | 0.9 | 13 | 1.8 | 8 | 0.5 | 13 | 1.1 | 21 | 0.8 | |||||

| Language Preparation School * | 124 | 13.4 | 73 | 10.2 | 54 | 9.5 | 42 | 9 | 178 | 11.9 | 115 | 9.7 | 293 | 10.9 | |

| TOTAL Participants | 926 | 100 | 716 | 100 | 567 | 100 | 467 | 100 | 1493 | 100 | 1183 | 100 | 2676 | 100 | |

**** 4 year schools & 4 year colleges, diploma,

** 2 year vocational schools, associate degree

* 1 year language preparation school

Daytime education, university students attending regular university classes, free of charge

Evening education, is a different concept of higher education, students participates evening classes, in the same department, like daytime students, but with a little charge of fee. It used to be utilized widely, but nowadays this evening education system are being gradually revoked.

Procedure

To increase the generalizability of the study, senior students of the faculty, college, vocational school and preparatory schools were chosen as participants, and questionnaires were handed to these students before the final examination week at the end of their first semester. The students were asked about the types of bullying and maltreatment that they had encountered over the 4 years (or 2 years for vocational schools and in that year for preparatory students) and for the last term with a questionnaire at the beginning of any class. The questions were designed to be very short and easy to understand, and it took about 10 minutes to answer the questionnaire. The students were assured that their participation was on voluntary basis and won’t be presented with any kind of prizes or gifts or college credits, and that only the researcher would see the answers. Ethical permission for this research was obtained from Institutional Review Board of the University. Furthermore, students were also given personal consent form for their voluntary participation.

Methods

To determine the association amongst the variables in this study, a non-parametric test, chi-square test, was mostly used in the analysis, and the significance of the test was evaluated using a confidence level at 0,05. In addition, the assumptions of the test (i.e., ordinal or nominal variables and independence of observations) were also evaluated appropriately before the analyses. Along with this, several descriptive statistics of the variables were calculated and reported. All the analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 21 (2012) and R (R Core Team, 2017).

RESULTS

As the data set is composed of categorical variables, a chi-square test was utilized in the analyses, and the significance level was accepted to be 0,05.

Significant differences were found between school types, genders and grade levels in terms of being threatened with being graded low or failed (p < 0,05). Table 2. No significant difference was found between types of education (p > 0,05). In other words, the daytime and evening students were threatened with being graded low or failed on the same level. The case can be seen in Table 4. There were 278 (10,4 %) students who answered the question “Have you ever been threatened with being graded low or failed?” To which 129 females and 149 males responded yes.

Table 2 Chi-Square Comparisons of Being Subject to Bullying in terms of Kind of Schools, Gender, Education Type and Grades Levels

| Significance for Faculty Bullying | Significance for Threat | Significance for Complain | Significance for Sharing | Significance for Witnessing | Significance for Student Bullying | |

| Kind of Schools | 0,000 | 0,000 * | 0,026 ** | 0,000 *** | 0,000 * | 0,000 * |

| Type of Gender | 0,194 | 0,007** | 0,211 | 0,062 | 0,468 | 0,001 * |

| Type of Education | 0,295 | 0,065 | 0,361 | 0,007 *** | 0,395 | 0,009 ** |

| Grade Level | 0,001 | 0,039 ** | 0,009 ** | 0,157 | 0,013 ** | 0,550 |

Significant at *=0,05 **=0,001 level

Table 3 Chi-Square Significance Test Comparisons

| TYPE OF ABUSE | SIGNIFICANCE FOR KIND OF SCHOOLS | SIGNIFICANCE FOR EDUCATION TYPE | SIGNIFICANCE FOR GENDER | SIGNIFICANCE FOR GRADE LEVEL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal | 0,000 ** | 0,075 | 0,032 ** | 0,000 * |

| Physical | 0,785 | 0,491 | 0,012 ** | 0,010 * |

| Social | 0,013 * | 0,014 ** | 0,182 | 0,186 |

| Sexual | 0,000 ** | 0,054 | 0,054 | 0,002 ** |

| Cyber | 0,205 | 0,620 | 0,302 | 0,039 ** |

Significant at *=0,05 **=0,001 level

To the question “Do you believe an objective assessment will be done when you report?” There were 108 (4,0 %) students who responded positively and 572 (21,4 %) negatively. Among them 38 (1,4 %) students said definitely yes, 132 (4,9 %) students responded yes, 203 (7,6 %) students responded slightly, 256 (9,6 %) students responded no, and 260 (9,7 %) students responded definitely no. There were 36 (1,3 %) students who answered yes when they were asked the question “Have you ever reported this adversity to any official authority in university in written?” Further, 135 (5,0 %) students answered ‘yes’ when they were asked the question “Have you ever reported what you went through to any authority or faculty member verbally or informally? As can be seen, the students looked for rather informal solutions. The students were asked whether they reported this adversity and uncivil behavior to the police or prosecution, 20 (0,7 %) of them reported it to the police and 6 (0,2 %) of them to the prosecution.

Table 4 Distribution of Violence Types by Schools and Total Victimization Rates

| SCHOOLS | VERBAL ABUSE | PHISICAL ABUSE | SOCIAL ABUSE | SEXUAL ABUSE | CIBER ABUSE | TOTAL YES | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Education Faculty**** | 161 | 26.4 | 9 | 1.5 | 38 | 6.2 | 106 | 17.4 | 25 | 4.1 | 213 | 35 |

| Business Faculty**** | 83 | 23.4 | 4 | 1.1 | 8 | 2.3 | 33 | 9.3 | 6 | 1.7 | 93 | 26.2 |

| Art & Silences Faculty**** | 35 | 14.6 | 1 | 0.4 | 3 | 1.3 | 6 | 2.5 | 5 | 2.1 | 43 | 18 |

| Engineer. & Architecture Faculty **** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Physical Education College**** | 25 | 21.9 | 5 | 4.4 | 4 | 3.5 | 11 | 9.6 | 5 | 4.4 | 32 | 28.1 |

| Nursing College**** | 6 | 23.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 23.1 |

| Physical Rehabilitation College**** | 3 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12.5 |

| Bolu Vocational School ** | 75 | 14.9 | 18 | 3.6 | 18 | 3.6 | 27 | 5.4 | 14 | 2.8 | 101 | 20.1 |

| Mudurnu Vocational School ** | 2 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 19 |

| Gerede Vocational School ** | 12 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 4.3 |

| Mengen Vocational School ** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 418 | 15.6 | 40 | 1.4 | 90 | 3.4 | 187 | 6.9 | 66 | 2.3 | 533 | 19.9 |

| Faculties **** | 313 | 22.4 | 19 | 1.4 | 54 | 4 | 156 | 11.3 | 42 | 3 | 390 | 28 |

| Vocational Schools ** | 88 | 8.9 | 18 | 1.8 | 31 | 3.6 | 29 | 2.9 | 23 | 2.3 | 124 | 12.6 |

| Language Preparation * | 17 | 5.8 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 19 | 6.5 |

| Daytime Education | 265 | 16.2 | 25 | 1.6 | 49 | 3 | 111 | 6.8 | 40 | 2.4 | 333 | 20.3 |

| Evening Education | 153 | 14.8 | 15 | 1.5 | 41 | 4 | 76 | 7.3 | 26 | 2.6 | 200 | 19.3 |

| Female Students | 220 | 14.7 | 16 | 1.1 | 47 | 3.1 | 111 | 11.1 | 45 | 3 | 288 | 19.3 |

| Male Students | 198 | 16.8 | 24 | 2 | 43 | 3.7 | 74 | 6.2 | 21 | 1.8 | 245 | 20.7 |

**** 4-year schools & colleges, ** 2-year vocational schools, * 1 year language prep. School

Differences were found between school types and types of education in terms of whether the students shared the adversity with someone (p < 0,05). No differences were observed between genders and grade levels (p > 0,05). It can be seen in Table 4. There were 494 (18,5 %) students who answered yes to the question “Have you ever shared this adversity with someone?” Whom have they shared it with, 164 (6,1 %) said “with a classmate”, 93 (3,5 %) “With a dormitory mate”, 20 (0,7 %) “With another faculty member”, 17 (0,6 %) “With the head of department”, 9 (0,3 %) “With family members”, and 223 (8,3 %) “With multiple people”.

The question “How important was this adversity to you?” was asked to see how it affected the student. There were 97 (3,6 %) students who answered, “not important”, 152 (5,7 %) responded “a little important”, 109 (4,1 %) said “very important”, 119 (4,4 %) reported “quite important”, and 106 (4 %) stated “very much important.” In total, 486 (18,2 %) students regarded this situation as an important incident. As for the question “How stressful was it for you?” 90 (3,4 %) students answered, “not stressful”, 151 (5,6 %) “A little stressful”, 106 (4 %) “Very stressful”, 107 (4 %) “Quite stressful” and 120 (4,5 %) “Very much stressful.” In total, 484 (18,1 %) students stated that this situation was stressful for them. To the question “How did it affect you?”, 53 (2 %) students responded in regards to their “emotional wellbeing”, 25 (0,9 %) regarding their “mental health”, 21 (0,8 %) in reference to their “academic achievement”, 28 (1 %) about their “attendance”, 100 (3,7 %) related to their “interest in the class”, and 335 (12,5 %) marked multiple choices.

While differences were observed between school types and grade levels in terms of witnessing a faculty member treating another student uncivilly (p < 0,05), no differences were found between genders and types of education (p > 0,05). To the question “Have you ever seen a faculty member treating another student uncivilly?” There were 845 (31,6 %) students who answered yes. The students who responded positively were asked about what kind of an uncivil behavior they encountered, where 640 (23,9 %) witnessed verbal bullying, 34 (1,3 %) physical bullying, 36 (1,3 %) social bullying, 24 (0,9 %) sexual bullying, 13 (0,5 %) cyberbullying, and 119 (4,4 %) witnessed multiple types of bullying.

There were differences between school types, genders and types of education in terms of students’ uncivil behaviors toward faculty members (p < 0,05). On the other hand, no difference was found between grade levels (p > 0,05). The students were asked the question “Have you ever treated a faculty member uncivilly?” and 97 students (3,6 %) answered yes. These students were asked “What kind of an uncivil behavior was that?” and 85 (3,2 %) reported verbal, 11 (0,4 %) physical, 7 (0,3 %) social, 6 (0,2 %) sexual, 5 (0,2 %) cyberbullying, and 12 (0,4 %) multiple types of bullying.

To the question “Why do you thinking you received the uncivil behavior or harassment?” 100 (3,7 %) students gave the answer “I did not meet my responsibilities”, 57 (2,1 %) said “my gender”, 9 (0,3 %) responded “my ethnicity”, 44 (1,6 %) stated “my physical appearance”, 30 (1,1 %) said “my political-ideological opinion”, 21 (0,8 %) reported “my religious faith”, 1 (0,0 %) responded “my physical disability”, 6 (0,2 %) said “my age”, 17 (0,6 %) responded “my hometown”, and 129 (4,8 %) marked multiple reasons..

As for the question “What were the characteristics of the faculty member who did the bullying and used uncivil behaviors the most?” The focus was on the gender, title and age of the faculty member who did the bullying the most. To the question “What was the gender of the faculty member who treated you uncivilly?” 85 (3,2 %) students gave the answer “woman”, 341 (3,2 %) responded “man”, and 63 (2,4 %) said “both”. The results of this study showed that the male faculty members exhibited violent and uncivil behaviors 4 times more than the female faculty members. To the question “What is the title of the faculty member that treated you uncivilly?” 29 (1,1 %) students gave the answer “lecturer”, 12 (0,4 %) said “expert”, 47 (1,8 %) reported “research assistant”, 107 (4,0 %) responded “teaching assistant”, 189 (7,1 %) said “assistant professor”, 20 (0,7 %) said “associate professor”, 72 (2,7 %) answered “professor”, and 76 (2,8 %) marked multiple faculty members. For the question “How old was the faculty member who treated you uncivilly?”, 39 (1,5 %) students marked the range between 21-30, 162 (6,1 %) said the range was 31-40, 121 (4,5 %) reported a range of 41-50, 81 (3,0 %) responded with a range of 51-60, 46 (1,7 %) said 61 and older, and 42 (1,6 %) students marked multiple ranges.

To the question “Where did this adversity happen?” 44 (1,6 %) students gave the answer “in the classroom at the beginning of the class”, 298 (11,1 %) “In the classroom during the class”, 22 (0,8 %) “In the classroom during the recess”, 11 (0,4 %) “In the hallway”, 14 (0,5 %) “At the canteen-cafeteria”, 43 (1,6 %) “In the office of the faculty member”, 19 (0,7 %) “Outside the campus”, and 125 (4,7 %) “In multiple places”.

What is the most observed type(s) of bullying in the Turkish higher educational system? Is there a type of bullying specific to the Turkish culture? One of the most striking results of this study is that the students being the victims of bullying in Turkey would not want to report it. This indicates the lack of trust and that adequate procedures which are yet to be established. The students share it rather with their classmates and hostel mates and receive help from them. Another finding about the Turkish university students is that there is almost no discriminating practice in place. There were very few students who reported that they believe there is discrimination due to their ethnicity, political opinion and hometown.

DISCUSSION

In this study, 10,4 % of the students were threatened with being graded low or failed. The male students were more likely to be threatened. Per faculty, the students in the faculty of education (22,3 %) received the most of the maltreatment, which was followed by the faculty of economics (9 %), and faculty of science and others (7,5 %). The cases of threat were most frequent in four-year schools (14,6 %) followed by two-year schools (7,1 %), then preparatory schools (1,7 %) respectively. It seems that the students were more likely to be threatened as the duration of education increased. Rautio et al. (2005) stated that failing the student or grading them low was observed in the medical school the most and it was followed by the faculty of education.

The results of this study show that students who are subjected to violence and maltreatment in Turkey hesitate about reporting it to official authorities. In this study, almost no participant wanted to report the incident to the head of department. It indicates lack of trust, perceived insensitivity of officials to the matter, and regards how much insensitivity has become institutionalized. In fact, these findings resemble the reactions of students in other countries as mentioned below. For instance, in the studies conducted by Rademakers et al. (2008) and Larsson, et al. (2003) the majority of students preferred to share experiences of adversity with their friends while very few of them reported it to an official authority. Nagata-Kobayashi et al. (2009) found that a minority of the students having such adversity in Japan reported the problem to officials. The majority of them did not report it to the department because they believed the problem would not be solved fairly, they feared that they would be accused and labeled. In the study by Bronner, et al. (2003), 30 percent of the Israeli students ignored mild or moderate sexual bullying and left the place of bullying while 40 percent of the students were subjected to more severe sexual bullying showed resistance. While mild and moderate sexual bullying was ignored by both genders, the female students reacted to severe bullying seriously and the male students more passively.

Whom do the students share the adversity with? There were 18,5 percent students who shared it with someone, while they preferred to share it with a classmate (6,1 %) and dormitory mate (3,1 %) the most. Scarcely anyone shared the adversities they had with management, head of department or family members.

As for how all these adversities affected the students, the findings showed that Turkish university students are not affected as severely and heavily as it is mentioned in the literature. This might be explained by the fact that they have frequently faced such maltreatments at home and schools since their childhood and they are accustomed to such incidents. On the other hand, Rademakers et al. (2008) states that bullying has an impact on students’ functionality, professional behaviors and job satisfaction. Bronner, et al. (2003) stated that Israeli students experience feelings of shame, fear and humiliation. Nagata-Kobayashi, et al. (2009) reported that students experience anger, reduced motivation, depression, and sleep disorders, loss of appetite, fear and thinking about dropping out amongst Japanese students.

Of the participating students, 31,6 percent witnessed a faculty member treating another student uncivilly, compared with 44 percent in the USA (Chapell et al., 2004). While there is a similarity in the rates compared with the foreign literature, the rates are lower in Turkey.

Few of the students (3,6 %) treated faculty members uncivilly, in a more verbal form. They stated that they did not show any other aggressive and uncivil behaviors. This indicates that the students were more careful and civilized toward faculty members because they were studying at a university, they were the adults and they were afraid of disciplinary penalty. This is the case at least from the students’ perspective.

Rates of being discriminated due to their ethnicity, political opinion and hometown were found to be little if any. Considering the differences among students, faculty members should prepare environments where all students can socialize and communicate and should strive for students to develop sensitive and respectful attitude toward differences.

As social discrimination and social violence are not easily observed and noticed, they do not attract much attention. Nonetheless, they have significant impact on the moods and mental health of individuals. Especially the university life, classes, group project assignments and socialization environments require being in a group. Being deprived of such an opportunity means being deprived of educational opportunities. Hence, penalties such as social exclusion and being kicked out of the group needs to be avoided and sensitivity about the matter should be enhanced. Similarly, Mukhtar et al. (2010) stated that students who are sad, alone, and have no close friends are more likely to be subjected to bullying. Bronner et al. (2003) found in their study in Israel that 90 percent of the students were subjected to some kind of sexual harassment while 30 percent of them were subjected to multiple types of sexual harassment. The authors also stated that the students were afraid and could not report the sexual harassment to relevant authorities, which makes it impossible to determine the actual prevalence. In this study, too, the students shared the problem rather with their friends and did not report it to an official authority.

It was observed in the study that assistant professors and teaching assistants were the faculty members who were reported to conduct bullying the most. Whereas Nagata-Kobayashi et al. (2009) did not find any difference between faculty members of different group ages in Japan, Mukhtar et al. (2010) in Pakistan and Larsson et al. (2003) in Sweden observed that professors were the most bullying faculty members and Rautio et al. (2005) found that research assistants and teaching assistants were the most bullying faculty members. The reason why associate professors resort to bullying the most may be related to the stress induced by the intense work load, research obligations and career concerns.

It was observed in this study that the male faculty members resort to bullying and violence 4 times more than the female faculty members. There may be a relationship behind the expected gender role of males and the patriarchal social structure in the Turkish culture. On the other hand, it was found that female faculty members resort to sexual bullying the most in Sweden (Larsson et al., 2003). Rigby (1996) mentioned about the prevalence of bullying behaviors among teachers. Accordingly, authoritarian teachers resemble authoritarian parents and are taken as models by students, therefore setting an example for bullying.

Schneider, Baker and Stermac (2002) stated that faculty members resort to sexual harassment and bullying in scientific environments where faculty members and students socialize together and at universities where there are no protective regulations and rules against sexual harassment in place. Socialization of students with faculty members in higher education is a natural part of education. However, it is necessary to develop certain awareness of where, in what frequency, and with whom it takes place. Socialization should occur in environments where there is not only one faculty member but more than one of them need to be present, and students and faculty need to meet professionally rather than personally.

Regarding the places where the incidents of violence took place the most, it was found that they occurred in the classroom during the class, at the beginning of the class and after the class, respectively. Bulut (2008) provided very similar findings regarding secondary education compared with higher education. It seems that uncivil behaviors are most frequent during class both in secondary and higher education. Very similarly, Larsson et al. (2003) also explored in their research in Sweden that the bullying incidents are most frequent during the class, workshops, and recesses. This might be prevented with a syllabus or verbal agreement to be signed between faculty members and students at the beginning of the term. Faculty members can express class requirements, and his/her expectations of students clearly, and in writing. It has been anticipated that such practice would prevent many possible problems.

The findings achieved in this study and the comparison of them with other countries shows that bullying is observed everywhere regardless of cultural, social and religious differences, gender, university, faculty and educational levels in all countries. It has been found that certain types of violence are concentrated in certain cultures and schools, which is due to the cultural and social context of the school. Indeed, all of the research findings address serious problems which are hidden and continue secretly. However, researchers are not able to investigate the problem and discuss the results due to the nature of insufficient reporting to administrators.

CONCLUSION

Some suggested preventive measures that can be taken are, to have written rules of conduct prepared, policies developed, and general awareness increased by universities and programs to help reduce the problem. In preventive studies, Benitez, Garcia-Berben and Fernandez-Cabezas (2009) explained that training teachers about the definition of bullying, characteristics of bullies and victims, and how this problem can be tackled in a course achieved very positive results. Then, bullying and violence can be explained to students in a course, or in seminars. Such programs can be provided with in-service training programs to teachers or faculty members, therefore presenting the matters to their attention and creating awareness. Next, students being the victims of bullying should be provided with psychological and social support, process of reporting and investigation should be started so that students will not be harmed anymore, and students should be supported throughout the process. This will increase students trust in the university, making it easier for them to report adversities. It is very important for students to receive the necessary legal support.

Lastly, universities and institutions need to have written principles on the matter, develop certain principles, and a policy to implement them in a widespread manner. Trying to hide the incident or resorting to informal ways will increase the problems. In a very decisive, serious and principled manner, victims and administrators needs to confront the incident and do what is necessary. Common sense, ethics and professional practices are the best advices. This study was conducted at one state university and with a selected group of participants, therefore there is a limited generalizability. Similar studies performed in different other regions and private universities will provide more realistic information. It is also recommended that each of the five types of violence addressed here be handled and examined individually and in a more detailed manner.

LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study was an exploration of faculty bullying and maltreatment at the higher education level. Generally, it is not accepted that those uncivil behaviors are happening in higher education. But unfortunately, the results are alarming. This research should be replicate in other countries and other colleges and universities. Qualitative research can shed more light on more deeper experience of bullying. Cross cultural differences should be looked at if there are any culture-specific type of bullying. Especially, since the Covid 19, e-learning become almost standard way of teaching so that cyber bullying and online interactions between faculty and students are important topics that has merit to be researched in further detail.

HIGHLIGHTS (KEY POINT)

It seems that faculty member are not very well trained for college classrooms and they are not aware of which behavior is considered rude and uncivil behaviors. It appears that sometimes student and faculty interactions sometimes get tougher, and it has negative consequences for students mental health and academic success. Students feel alone and they do not know where to go and to whom talk to. It should be a clear guideline and some formal training for students as well as faculty members.

Bullying has been extensively researched in primary and secondary education but there is a need to understand the prevalence and nature of bullying and uncivil behaviors at higher educations. Faculty members and teachers are not immune to these behaviors. Results provide high prevalence rates of bullying behaviors, especially psychological and verbally abusive behaviors. It seems that each department and major fields has its own characteristics that make students vulnerable to uncivil behaviors. People who are working closely and long hours together are more prone to abusive behaviors. Understanding and awareness of bullying is also important concept even for college professors.