Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Estudios Socio-Jurídicos

versión impresa ISSN 0124-0579

Estud. Socio-Juríd v.13 n.1 Bogotá ene./jun. 2011

Liliana Lizarazo-Rodríguez*

University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium

* Lawyer, Universidad del Rosario; PhD Researcher, University of Ghent (Belgium); independent legal consultant. E-mail: lilianalizarazo@skynet.be

Fecha de recepción: 31 de enero de 2011

Fecha de aceptación: 18 de marzo de 2011

ABSTRACT

Colombia is mentioned, together with the US, Uruguay, Argentina and Mexico, as one of the first countries worldwide to adopt the judicial review as a means for adjudicating on the constitutionality of legislation. In recent years, and particularly since the enactment of the Political Constitution of 1991, the Colombian Constitutional Court is also mentioned as a notorious example of judicial activism in terms of legislating through the constitutional adjudication process. This article presents a literature review on the globalization of judicial review and the contemporary methods of constitutional adjudication (including the balancing method), in order to assess the uniqueness and avant-garde nature of constitutional adjudication in Colombia in the global context. Brief reference is also made to the literature on the institutional limitations faced by less developed countries, inasmuch as they affect the way constitutional adjudication is applied and perceived.

Keywords: constitutional adjudication, judicial review, balancing method, institutional quality, Colombian Constitutional Court, case law transplant.

RESUMEN

Colombia, junto con otros países como los Estados Unidos, Uruguay Argentina y México, se presenta como uno de los primeros en el mundo en adoptar el control abstracto de constitucionalidad de las leyes. Recientemente y en especial desde la promulgación de la Constitución Política de 1991, la Corte Constitucional de Colombia es presentada como un ejemplo notorio de activismo judicial que crea normas jurídicas a través de sus sentencias. Este artículo presenta una revisión general de la literatura sobre la globalización de la acción de revisión constitucional, así como de los métodos contemporáneos de interpretación y de decisión constitucional (incluyendo el método de ponderación), con el propósito de posicionar el caso de Colombia en cuanto a su grado de particularidad y su carácter de vanguardia en materia de interpretación constitucional. Se hace también una breve referencia a la literatura que analiza las dificultades institucionales de países en desarrollo que inciden en las consecuencias de las sentencias proferidas por la Corte Constitucional y su evaluación.

Palabras clave: control abstracto de constitucionalidad, juicio de ponderación, trasplante de jurisprudencia.

RESUMO

Colômbia, com outros países como os Estados Unidos, o Uruguai, a Argentina e o México, se apresenta como um dos primeiros no mundo em adotar o controle abstrato de constitucionalidade das leis. Recentemente e em especial desde a promulgação da Constituição Política do ano 1991, a Corte Constitucional da Colômbia é apresentada como um exemplo notório de ativismo judicial que cria normas jurídicas através de suas sentenças. Este artigo apresenta uma revisão geral da literatura sobre a globalização da ação de revisão constitucional, assim como dos métodos contemporâneos de interpretação e de decisão constitucional (incluindo o método de ponderação), com o propósito de posicionar o caso da Colômbia em quanto a seu grau de particularidade e seu caráter de vanguarda em matéria de interpretação constitucional. Também se faz uma breve referência à literatura que analisa as dificuldades institucionais de países em desenvolvimento que incidem nas conseqüências das sentenças proferidas pela Corte Constitucional e sua avaliação.

Palavras chave: controle abstrato de constitucionalidade, juízo de ponderação, qualidade institucional da Corte, Corte Constitucional da Colômbia, transplante de jurisprudência.

INTRODUCTION

Colombia is mentioned, together with the United States (US), Uruguay, Argentina and Mexico, as one of the first countries worldwide to adopt the judicial review as a means for adjudicating on the constitutionality of legislation.1,2 In recent years, particularly since the enactment of the Political Constitution of 1991 (P.C.), the Colombian Constitutional Court is mentioned as a notorious example of judiciary activism in terms of legislating by means of its judicial review sentences with erga omnes effects, as well as through Actions of Protection of Fundamental Rights (A.P.F.R.).3 Even though the constitution did not conceive judicial review as a source of law, it is viewed as a political competence with limited negative legislative effects when it nullifies a law, but lacking the competence to create new legislation. However, the Constitutional Court has been accused of usurping legislative competences through interpretation,4 primarily through the discretionary use of conditioned decisions and the adoption of interpretation techniques borrowed from common law, such as precedent analysis.

According to Cepeda, the Constitutional Court has adopted a practice of conditioned ("modulated") decisions whereby instead of striking down a law altogether, it upholds a provision under the condition that "only some ... interpretations are valid, while others are unconstitutional and must be rejected".5 These conditioned rulings have been used "in a discretionary way",6 which not only has the effect of changing the contents and effects of legislation over time, but also changes the rules of constitutional adjudication because this practice is not based on any explicit constitutional competences granted by the P.C. (241) but on the practice of other Constitutional Courts.7

The Colombian Court has also adopted methods of interpretation generally associated with common law, such as the technique of precedent analysis, which sometimes has been criticized because the Court apparently did not fully take into consideration its implications and theoretical developments,8 although it has also sometimes been defended (when used as in the US).9,10 This is not unique to Colombian constitutional case law. The absence of precedents in civil law systems is often considered a source of instability in some areas of legal practice.11,12 An informal structure of precedents is sometimes promoted in civil law countries in order to improve legal certainty in areas where it cannot be attained through codification, to increase judicial productivity (caseload management), to reduce the vagueness of statutes and general principles, and to decrease the number of disputes and legal costs.13 These practices, more than a case of 'legal transplant'14 are rather a 'case law practice transplant' in which the level of acceptance or rejection depends on the amount of judicial discretion.15

Judicial discretion is considered a differentiating feature among legal systems. It is widely accepted that common law systems offer a large degree of judicial discretion whereas civil law countries privilege "legislative rulemaking".16 Unlike the US, European legal systems tend to limit judicial discretion and to protect legal formalism. However, economic integration and globalization are phenomena that favor the expansion of judicial discretion and increase the relevance of other schools of thought such as legal pragmatism.17 Another perspective presents the globalization of the law as a phenomenon in which some countries are places of "production" of legal thought and others are places of "reception";18,19 this reception mainly occurs through foreign citation and "case-law transplant".

This article reviews the international literature on the development of judicial review and outlines judicial review in Colombia within this global context. In addition, it presents the literature on contemporary methods of constitutional adjudication and assesses whether the Colombian case is actually as unique and avant-garde in this regard as is sometimes claimed. Finally, international literature that highlights the institutional limitations of judicial activism in less developed countries is briefly reviewed, focusing on how said limitations affect the way legal theories are applied by the judiciary and the way constitutional adjudication is evaluated.

1. INTERNATIONAL MODELS OF JUDICIAL REVIEW

The establishment of judicial review in the US20 at the beginning of the 19th century had an important impact in Latin America, although not immediately. Neither was it the only influence, given that the 'constitutional court' model formulated by Kelsen early in the 20th century was also relevant. In Kelsen's view, any indeterminacy of the Constitution was a matter to be resolved by the legislative, and not by the judiciary, and principles were thus excluded from adjudication. This supremacy of the legislative was not shared by the US System which gave supremacy to the judiciary.21 The institutionalization process of judicial review has also been described as a series of waves.22 Ginsburg identified the first wave with the creation of judicial review in the US. The second wave was the development of Kelsen's theory and the creation of an independent Court. He clarifies that despite the generalized view that this corresponds to the European model, only "post fascist" countries adopted it: Austria, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain, because of the need to define fundamental rights and to limit public powers. It expanded afterwards to other countries mainly to protect fundamental rights. The third wave corresponds to the fall of the Berlin Wall which extended the wave to Eastern Europe and Central Asia as well as to other countries in Africa and Asia.23,24

This explains why many countries implemented judicial review after World War II,25 but there is no consensus as to the preferred constitutional model of judicial review or on the establishment of a specialized constitutional tribunal. It has been largely affirmed that the expansion of the "principle of constitutional review" is a result of the paradigms of the rule of law and the separation of powers, which have been broadly established in the main international human rights treaties.26 However, the main models of constitutional review continue to be the European and the American ones, whose main differences are the centralized or, otherwise, diffuse nature of the control of constitutionality and therefore the creation of a supreme court (sometimes with a specialized constitutional chamber within the court) or an independent constitutional court.27 However, in academia there are diverse opinions as to which of these models is more prevalent worldwide.

US judicial review is considered to have influenced even European continental law, where the absolute discretionary competence of the legislative has been reassessed due to the implementation of constitutional principles.28,29 Moreover, the US legal system is possibly the most significant source of inspiration for the worldwide expansion of judicial review as a means for controlling the other powers. "[T]he rise of transnational jurisdictions", i.e. the growing importance of international financial institutions at the international level, as well as the power of US law firms on issues regarding the "globalized economy and the non-profit NGO sector" are phenomena identified as strongly influencing the expansion of this legal system.30

Within the general European model, the Austrian and the German models (in that order) have been the most influential worldwide.31 The German Constitution created a modern form of judicial review that focuses on the protection of rights as the main goal. Judicial review seeks therefore to avoid the implementation of policies that are contrary to the constitution, thereby affecting the traditional separation of powers.32 Although the influence of US judicial review is accepted worldwide, the difference is that this "European" judicial review seeks mainly to protect rights and consolidate democracy.33 For many observers, jurisprudential and case law developments worldwide have moved closer to the German model, mainly due to the generalized adoption of the balancing method of adjudication, the enforcement of constitutional rights and the power to declare legislative omissions as unconstitutional.34 The latter seeks to make the legislative responsible, without any specific and mandatory mechanism of enforcement; enforcement depends therefore on legislative action, which usually should legislate even if the rulings declaring the omission may extra-limit the competences of the judiciary. According to some opinions, the most important incentive to act seems to be "a sheer interest in complying with the constitution".35 Others see it as yet another source of tension between the legislative and the judiciary, because it is mainly used by the neo-constitutionalist approach with a large axiological content.36 This figure on legislative omissions has also been adopted by constitutional case law in Austria, Spain, Italy, Argentina, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea and Taiwan.37 Some countries have even incorporated this figure in their constitutions, such as in ex-Yugoslavia, Portugal, Brazil and Venezuela.38

Moreover, the German model of a constitutional court has lately been more significant worldwide than the US model because a specialized tribunal is often preferred to a high court with constitutional functions, and because few countries choose life tenure for justices.39 In addition, modern constitutions, enacted after 1945, generally protect Economic, Social and Cultural (ESC) rights, based on "a flexible and pragmatic style of interpretation and enforcement" which seems closer to the German model.40 This model has been widely adopted in countries with recent democracies and is becoming the most influential model outside the US. Additionally, the German court accepts both abstract and concrete judicial review, a model that has also been adopted by Spain41 and other countries.

The French model is sui generis in Europe in that the myth of the rational legislator has been strongly defended. The Constitutional Tribunal was created as an appendix of the legislative to control whether the judiciary complies with the legislative intention; as a result, the general rule has been that challenges to statutes are only possible before their enactment.42 Judicial review by the Conseil Constitutionnel has been seen as a way to improve the policy-making process and justified as a means of avoiding statutory reforms because it enables the judiciary to update laws.43 However, this tribunal has evolved in the direction of other European courts as far as the protection of fundamental rights is concerned. This was particularly evident since the incorporation of the Declaration of Human Rights in the preamble of the French Constitution,44 but it was constitutionally established by the constitutional amendment (61-1) in 2008, and the corresponding Organic Law of 10.12.2009 under the figure of the "question prioritaire de constitutionnalité". Any person who is part in an ordinary or administrative process has the right to challenge a legal rule (enacted by the legislative) that may violate the rights and civil liberties granted by the Constitution. However, it is still a very restricted action because it must pass two filters (the competent judge of the process and the Council of State or the Court of Cassation, depending on the jurisdiction) before it is reviewed by the Constitutional Tribunal.45 Although it represents an evolution vis-à-vis the "dogmas of parliamentary sovereignty",46 its application is too recent (since 2010) to be evaluated.

The exponential growth of the importance of judicial review and of the number of countries that include it in their constitutions48 is presented in a study of Constitutional Courts worldwide. It found that in 2003 almost 85% of the countries had some sort of judicial review, 46% of them through a Constitutional Court, the remainder through ordinary courts. No evidence was found that Constitutional Courts were less likely in common law legal systems.49 In developing countries, the Constitutional Court of South Africa for instance has also used judicial review as a means to help resolve nonne-gotiable conflicts.50 Even though Latin American judiciaries belong to the civil legal system, they are influenced by the Common Law system (US model),51 as well as by the Austrian model of constitutional control mainly through the creation of a specialized body to analyze the constitutionality of statutes and the erga omnes effects of their rulings.52 The German model was received indirectly through the Spanish model. Although the Colombian judicial review system is one of the oldest in the world, the constitutional design of the Colombian Constitutional Court in 1991 and its further developments through the adoption of constitutional case law show a remarkable influence of the German model, as occurred in other countries where the institution is quite recent.

2. CITATION OF FOREIGN DOCTRINE AND LAW

A relevant aspect of the adoption of international trends in judicial adjudication, which also depends on the institutional capacity of the courts, relates to the citation of foreign doctrine and law. Mainly two approaches try to explain the phenomenon. First, 'normative universalism', an interdisciplinary theoretical approach combining comparative constitutional law and international human rights, promotes the use of general principles to protect human rights worldwide. Second, 'contextualism' follows comparative constitutional law in terms of highlighting the particularities of each country,53 and focuses on the potential changes that a "borrowed institution" may suffer once "it crosses the border", and the possibility that imported institutions may have national roots in spite of their appearance in international bibliography.54

Judicial globalization is characterized by the frequent application of the balancing method and by mutual citation in human rights matters, called the "new ius gentium of human rights".55 This phenomenon is an aspect of a new form of globalization of the law (called 'the third globalization') where institutional innovation is crucial (cf. structural adjustment, economic integration, organizations etc.).56 This movement is seen as the conclusion of a long process in which rights have gained increasing relevance, "to become the universal linguistic unit". Sometimes they take the form of rules and sometimes of policies, but in any case they are highly relevant, even if they are not part of the constitution.57

Despite the remarkable global influence of its legal system, the US judiciary has hotly debated the question of whether it should consider using foreign and international case law, legislation or doctrine. Justices Breyer and O'Connor justify the potential use of international materials because globalization and the diffusion of the protection of human rights have an incidence on US constitutional cases.58 Justice Scalia opposes this possibility because it is not in line with the meaning of the US constitution.59 Other arguments against the citation of foreign legal materials include the following: (i) It promotes judicial activism because judges have an unlimited choice of sources, increasing the "risk of selection bias" and personal preferences, thus menacing the rule of law;30 (ii) It facilitates the participation of pressure groups in adjudication, seeking the inclusion of principles not contemplated in the constitution that benefit their own interests; (iii) it affects legal certainty because citizens do not know the applicable law and the constitutional competences concerning lawmaking powers are ignored;61 (iv) the complexity of the social, political and cultural contexts complicates the understanding of foreign law and doctrine; (v) it is "opportunistic" because it disguises the presentation of personal opinions. It mystifies "the adjudicative process and disguises the political decisions that are the core of the Supreme Court's constitutional output".62 Therefore, world constitutionalism is not a strong source for US constitutionalism.63

Although foreign citation may be seen as arbitrary, it has become a common practice in new constitutional regimes. The phenomenon of "bottom-up globalization" explains how the global circulation of interpretative paradigms among judicial systems creates new relations of interdependence, different from the traditional mechanisms of competences of the executive and the legislative.64 In developing countries, contrary to the US, foreign citation by constitutional courts is the general rule.65 The Colombian and South African constitutional courts are seen as examples of great receptivity to legal concepts developed in foreign countries.66 Defenders of this practice justify its relevance in the case of international treaties, and support the use of the dynamic method of interpretation, based on "background drafting and negotiations materials", over the textualism that would ignore the nuances of the different legal systems and would impede the creation of a transnational jurisprudence.67 Another argument in favor of foreign citation is based on natural law, which assumes the existence of universal principles that give the framework to positive law. Said universal principles are supposedly "visible in foreign legal systems" and their citation would provide "evidence of universality". However, critics argue that no consensus exists on the actual contents of natural law and suggest that the solution may be to find a "global judicial consensus".68

3. THE GLOBALIZATION OF THE BALANCING METHOD

Balancing is widely considered to have become a "globalized" method used by national and international courts to adjudicate in constitutional and human rights matters.69 It has been described as a "viral" phenomenon because it expands rapidly from one jurisdiction to another and then worldwide,70 and because "the language of balancing -and proportionality- has become a new lingua franca of courts and constitutional scholars around the world".71 Balancing has also become one of the characteristics of globalized legal thought72 with a high level of impact on constitutional interpretation.73

The crisis of legal formalism is attributed partly to its incompatibility with globalization.74

Comparative law has attempted to design methods to analyze the topic;75 the similarities among courts in the adjudication on human rights issues are widely cited, but the differences have not received the same attention.76 However, "comparative judicial balancing" seems difficult to assess due to the "ambiguities and dualities" in the terms that prevent finding "common terms of reference" and the great differences in context and institutions among countries.77 The global adoption of balancing is also criticized because it was constructed based on a particular type of European rationalism, and it therefore should not be presented as a universal theory because the circumstances of particular cases that determine moral judgments are ignored and may have an ethnocentric perspective.78

The generalized use of balancing as a procedure that "combine(s) the universal -the interest to be balanced- with the local, the context within balance" is complex because "apparently small differences in detail can have consequences, both doctrinally and practically".79 In fact, balancing differs strongly among courts. In the US, for example, balancing tests exclude the "principle of proportionality", whereas in Germany balancing is highly associated with values that are supposed to have "a strong universal dimension".80 The proportionality test, at the core of the balancing method, is based on the German doctrine, which was later disseminated to Europe,81 the Commonwealth systems, and Central and Latin America. At the international level, the European Union, the European Convention of Human Rights and the World Trade Organization frequently choose it as a method of interpretation.82 Human rights NGOs are among those who advocate the globalization of constitutional law. Pressures also come from "transnational treaty bodies whose decisions have domestic constitutional implications", such as the European Court of Human Rights.83 One explanation for the fact that international constitutional doctrine is more readily adopted in fundamental rights issues than in structural issues is that the latter tend to be associated with domestic politics and are therefore not as susceptible to globalization as human rights.84

Latin America has been highly receptive to foreign legal theories and methods of interpretation. For instance, Latin American legal positivism is regarded as a mixture of the theories of Kelsen and Hart which, in some circumstances, allow judicial discretion.85,86 The first North American analysis of Latin American legal philosophy concluded that in the first part of the 20th Century Latin America experienced a strong continental European influence, particularly from Germany and Austria.87 According to López, local law systems (systems of reception) developed the legal theories on the systems of production in a distorted way.88 In Latin America, curiously, the "reasonability principle" was initially used to control discretionary acts of governments.89,90 A study focusing specifically on the reception of the two standard methods of balancing (European and US) in Mexico and Colombia, concluded that the models has been "tropicalized" through local adjustments and the addition of new elements.91,9292 This study found that the Colombian Court explicitly cited comparative law, particularly German and US doctrines, whereas the Mexican Court adopted the Colombian model without citing it expressly.93

4. THE RECEPTION OF INSTITUTIONS IN COLOMBIA

It is generally recognized that Colombia has a mixed legal system with a dominant structure belonging to the continental system but with a non-negligible influence from US constitutional law. Colombia received strong influence from the French Exegetic School in the area of civil law, as well as in the design of the administrative jurisdiction, and this French influence was also visible in constitutional matters before the P.C. of 1991, particularly in the generalized application of the thesis of the "rational legislator". This is not the situation in the case law of the Constitutional Court since 1991, which hotly debated this idea and the exegetic reading of the P.C.

One of the influences of the US model of judicial review is the diffuse control of constitutionality, performed by any judge in particular cases with limited consequences beyond this case, and known as 'exceptional constitutional control' in Latin America.94 A second issue is the presentation of concurring and dissenting opinions in US case law,95,96 as well as in Colombian Case Law. Thirdly, the participation of third parties in the process is possible in the US system. They are called "the brief Amicus Curiae" and they are considered a means for providing information to the Court but also as a potential source of influence by interest groups.97 Figures show that they are presented mainly by civic organizations, interest groups and the government and that they have considerable influence on justices:98 "It is a partisan brief filed by an outside individual, corporation, governmental unit, or group who is not a litigant in the suit but is vitally interested in a decision favorable to the side it espouses".99

Another perspective is that "Amicus curiae briefs sometimes try to fill empirical gaps (...) but these are advocacy documents, not subject to peer review or other processes for verification" and therefore judges cannot entirely trust them and are obliged to follow "their own intuitions".100 A fourth similarity is the institution of Law clerks. They are also considered a court "pressure" group and have even been considered a power "behind the throne". They are appointed discretionally by justices,101 and are capable of influencing the courts' use of precedents.102 Some assessments of their work are not very positive; they have been accused of being responsible for the length and "superficial erudition" of the present rulings of the US Supreme Court.103 In Colombia their appointment is also discretionary and although their role has not been the object of study, the conclusions would probably be the same. A fifth similarity refers to the discretionary competences of the US Supreme Court, which has been described as having almost total control "over its docket, deciding in an entirely discretionary way which cases it wants to consider in detail".104 This is similar to what occurred in Colombia in the selection of the A.P.F.R. cases, which has been widely criticized because the selection may reflect the specific ideological interests of the Court. Finally, the severability clause, which is generally accepted by the case law of the US Supreme Court, takes the form of modulated rulings in the case law of the Colombian Constitutional Court; these rulings have been understood as one of the manifestations of judicial activism because the Court completes or reforms statutes submitted to its analysis when they are partially struck down. However, the differences are also numerous, the most notorious being the results of the exercise of the judicial review. Abraham presented a synthesis of the declarations of (partial or total) unconstitutionality of federal statutes by the US Supreme Court. In two centuries (1789-1997) they amount to 151105 which stands in stark contrast with the Colombian Constitutional Court, which in only two decades of existence has issued a much larger number of rulings.

The influence of the German model has been more notorious in Colombian constitutional case law than in the text of the Constitution. However, the design of a Constitutional Court with an open system of litigation in which everyone has access to the court, including ordinary judges who may also submit consultations to the Court,106 has clear similarities with the German model. Other specific features of Colombian constitutional case law that were clearly influenced by the German model are, first, the adoption of the balancing method to protect constitutional rights and the possibility to declare the unconstitutionality of legislative omissions. Second, the interpretation adopted when some statutes are considered unconstitutional but they are not struck down in order to preserve the caused effects. This is known as the constitutional conformity interpretation ("verfassungskonforme Auslegung") which rules on a specific interpretation of the statute, which the authorities are required to comply with.107 In Spain these types of rulings aimed at controlling the actions and omissions of legislators are also accepted: 'interpretative' sentences present meanings of a law and also consider the motivations to be part of the decision, and 'constructive' sentences show the modifications needed by a law in order for it to be constitutional.108 This figure is equivalent to the Severability Clause in the US system. Both are clearly antecedents of the modulated rulings of the Constitutional Court. However, a notorious difference with the German Model is the "political question" used by the US Supreme Court of Justice and by the Colombian Constitutional Court to intervene in political issues. This is rejected by the German Court through the adoption of the doctrine of judicial self-restraint,109 which is highly recommended in order to restrain judicial activism.

In general, two tendencies in Colombian constitutional adjudication have been identified: the "traditionalist-positivist" tendency that does not differ from statutory interpretation, and the "new constitutionalism", which uses a broad interpretation of constitutional principles. The hypothesis put forward is that the first tendency is dominated by judges following a judicial career path whereas the second is promoted by judges with an academic background. Whereas the Supreme Court of Justice followed the first tendency before the P.C. of 1991,110 the Constitutional Court followed the second, based on the implementation of the doctrine of precedents and modulated rulings which strengthen the law-making role of the judiciary. This "neo-constitutionalist" form of adjudication supposedly promotes transnational and social-focused rulings.111

Taking into account the framework of the P.C. of 1991, a study concluded that this constitution promotes less accountability in order to enable the Court to play an active role in the construction of democracy and rejects a very independent court because it would not have incentives to act in this way, as occurred with the Colombian Supreme Court before 1991.112 The new constitutional procedure of concrete judicial review (A.P.F.R.) and the new method of rights analysis (balancing) have empowered the Court to protect the rights of social groups excluded from political power. This way, concrete judicial review is perceived as having greater democratic relevance than abstract judicial review, because citizens have the possibility of presenting claims, which creates a sort of political capital for the courts based on a culture of rights, and places case law at the center of the political debate.113 The Constitutional Court has thus displaced legislators as main guardians of rights and has abandoned legal formalism as its primary method of interpretation, privileging the use of the balancing method instead. This analysis also assumes that this change is related to the academic background of justices, who had the opportunity to follow worldwide trends on balancing and to put the Colombian Court at the forefront in Latin American in terms of the justiciability of rights.114 This way, it helps "deepen the social basis of democracy" in a country with high inequalities.115 Therefore, judicial activism is not considered more dangerous in developing democracies; it attracts lawyers educated under the progressive Warren Court and therefore, it may "provide better democratic outputs" with a "pragmatic, flexible approach rather than a formal approach to interpreting constitutional guarantees".116 Again Colombia together with Mexico are presented as examples of the trend towards empowering high courts as a way to consolidate democracy,117 highlighting that the agenda of the Colombian Court is more ambitious and its judicial activism is seen as a crucial driver of democratic transformations.118 The transformation of Colombian constitutional case law, using the US system as a model to promote judicial activism is also argued by Rodríguez.119

The P.C. of 1991, as many modern constitutions of developing countries, has been categorized as an "aspirational" constitution, as opposed to a "protective" one. The (sociological) characteristics of aspirational constitutions are the maximization of objectives through rights and principles and the promotion of judicial activism, whereas in protective constitutions constitutional rights are political matters to be addressed by Congress. In aspirational constitutions there is normally an enormous difference between the objectives and social reality, and they therefore seek to improve these realities.120 Judicial activism in Colombia is justified by "the crisis in representation and the weakness of the social movements and opposition parties".121 The enormous political fragmentation in Colombia is another justification because the other powers have not had the capacity to threaten the Court's institutional stability and the Court has felt supported by public opinion.122 Constitutional judicial activism has also been made responsible for the "constitutionalization of daily life" in Colombia, creating the image that constitutional rules have changed social reality with an "anti-hegemonic character". However, an instrumentalist evaluation of constitutional case law considered that these purposes failed because neither peace nor less social inequality have been achieved; case law has only succeeded in gaining importance because of the weakness of the other powers.123 These conclusions are not generally shared because constitutional case law is supposed to favor the emergence of social movements that may have apparently already reached their social objectives, as in the case of housing, health and wages.124

Although other authors agree that the Colombian Court is the most notoriously activist court in Latin America, they do not necessarily agree that judicial activism is one of the main contributors to the country's welfare.125 Critics of this judicial activism think that the complexity of economic regulation and economic social and cultural (ESC) rights represents a challenge for constitutional case law argumentation.126

The worldwide trend towards the use of discretionary competences to choose the methodology and to adjust the parameters of interpretation to the context may produce memorable or even dangerous constitutional case law. Accountability, incorporated through "the reserves of interpretation" inside and outside the Constitution, has been highly recommended.127 However, the task of designing objective criteria to limit the interpretation competences of the Constitutional Court, particularly in cases where the effectiveness of rights and constitutional principles leads to striking down or conditioning economic reforms, is also a great challenge because this regulation would also be interpreted in a discretionary manner.128 The public choice approach considers that judicial behavior can reflect the agendas of the judges or an agenda imposed by pressure groups129,130 and rejects the hypothesis that judges seek to realize the ideals of the Legal Social State because not even Congress and government do so.131 A more radical criticism concerning the justiciability of ESC rights states that the rulings of some Latin American Constitutional Courts, by adopting the 'Neo-constitutionalist' methodology, extra-limit their competences, politicize justice,132 seek to legislate without democratic representation and privilege personal preferences disguised as "pseudo-scientific postulates".133,134

Some recommendations suggest that in a representative democracy conflicts concerning social interest should be analyzed and, if possible, solved by the Legislative; consequently, courts should not adjudicate by ordering budget allocations or usurping budgetary legislative competences.135 Moreover, it is suggested that extra-constitutional parameters to limit constitutional adjudications should be included such as: (i) international law standards; (ii) comparative law; (iii) empirical parameters; (iv) the historical context of the constitutional rules.136 However these parameters are precisely the ones the Court uses to justify its rulings and judicial activism, and the same reasons for which they are also rejected in US doctrine.

Foreign citation in Colombia was analyzed by López.137 He stated that "anti-formalism" in Colombia was introduced by the Constitutional Court, applying a "new version" of Kelsen's theory138 and a "Latin American" version of the theories of Hart, Dworkin and Alexy, and that most of the main Colombian authors of this reception have been law clerks of the Constitutional Court.139 An analysis of justices during the 1991-2003 period concluded that Hart, Dworkin and Alexy are indeed the authors who are most frequently cited by them. Some justices had a clear and coherent citation pattern, whereas others tried to combine some of these theories, and as a result it was not feasible to present a clear tendency for the Court as a whole.140 Another interesting finding was that when the Court sought to put fundamental rights above the legal order, it based its arguments on authors like Radbruch, Holmes, Frank, Cardozo and Hart.141 The use of principles alongside rules based on Dworkin and Alexy has also been systematically integrated by the Constitutional Court.142

More concretely, the application of the balancing method by the Colombian Constitutional Court has been analyzed with contradictory hypotheses and conclusions. A first study states that the Constitutional Court seeks to give a normative character to constitutional principles through the binding force of case law but also through jurisprudence, mainly based on the German model.143 The use of this balancing method is justified by the need to highlight other constitutional principles besides those of the Legal Social State.144 The Court is said to be a political body trying to enforce its position through the introduction of vertical precedents and the use of "tests" in the balancing judgment of conflicting rights.145 The use of the balancing method sought to diminish the influence of textualism, historicism and systematic interpretation146 because textualism is not adequate provided that constitutional principles are undetermined and their scope is given by moral and political contents that may not be interpreted by this method. Originalism and legislative history, highly used in the US to avoid judicial discretion, is not applicable in Colombia because both the P.C. and the Proceedings of the National Constituent Assembly are so recent. As a result, instead of reviewing the original intent of the articles, it is possible to examine the positions of different groups that participated in the Assembly. The Court has used this method but it has also been questioned in dissenting opinions.147 Therefore, the purposive and systemic interpretation is the recommended method for constitutional adjudication.148 López considers the US model as a guide for the balancing method and the "reasonability test". He also supports the use of the "equality test" and the theory of intensity on these tests, because these procedures promote the 'objectivity of constitutional adjudication' defended by Dworkin and Alexy.149 However, despite the high relevance that is attributed to the balancing method, it is not applied systematically and other traditional methods are still used.150

This study151 is an example of the complexity of case law transplant and the way it is has been integrated into Colombian constitutional case law. The study is part of a training course for the judiciary and it is almost completely based on a US bibliography although it also extensively quotes C022/96, which mainly refers to German and European human rights case law. Moreover, the author concludes that the Colombian constitutional case law works on 'jurisprudential lines' along which "sub-rules of constitutional law" have been created and presented as "law" to the judiciary152 He recalls that the binding character of case law was accepted in Colombia by C037/96, based on a re-construction of the concept of "constitutional doctrine" and the use of the equality principle of the P.C. (13). C836/01 extended the doctrine of the precedent to other high courts (Council of State and Supreme Court of Justice).153,154 However, this opinion is not unanimous because other judicial opinions reject the binding force of precedent. This study adopted one of the multiple common law techniques to be taught to Colombian judges,155 in an attempt to create a theory of the Colombian precedent as a mandatory source of law.

Another study states that the use of the balancing method in Colombia has increased the number of justiciable rights and the direct application of the P.C, overriding statutes in order to protect the Legal Social State. This way, many controversies have arisen with economic implications. This situation is justified by the fact that the P.C. imposes normative restrictions on economic policy because it recognizes the normative force of ESC rights, which implies that the design of economic policies should respect those rights. The study defends the constitutional control of economic policies by way of the reasonability test, i.e. the Court should not only analyze whether the objectives of a reform are in line with the P.C. but also that the means are "potentially adequate" for the intended purposes.156

By contrast, a former justice of the Court criticized the way in which the balancing test has been applied because the Court confuses and mixes the European proportionality test with the American equality test.157 He argued that when the Court applies the proportionality test, it analyses the means but not the necessity of the reforms and, therefore, it should have declared many reforms to be unconstitutional. He added that the analysis should also include a "cost/benefit analysis", weighing the benefits of a reform against the limits imposed by the rights.158 He opposes the use of US jurisprudence in reference to the equality test because the context of Colombia is highly different and because constitutional control should always consider the bases of the Legal Social State.159,160 The use of the "intensity test", based also on US case law, which proposes flexible control in economic, fiscal and international matters, is judged as arbitrary because it is not established in the P.C. (241) and the Court lacks the competence to regulate this procedure.161,162 This author concludes, first, that the Court is using the reasonability test not only to limit legislation, but mainly to implement "axiological voids". As a result, the reasonability test is a powerful tool that enables the Court to use discretionary competences to create legal voids. Secondly, interpretation based on values and principles lacks definition and hierarchy and it therefore causes legal uncertainty.163

A more recent study concluded that the Colombian court applied the "reasonability test" seriously164 It is a "European inspired reasonability test that links equality to proportionality in the German sense". However three types of tests were distinguished in Colombian case law: "a European test which is based on proportionality with equal intensity; an American test that distinguished different levels of intensity, and a combination of the two" (C093/01, quoted by Bernal Pulido (sd: 5, 8, 13), quoted by Conesa 2008:9). It is a 'tropicalized' model, combining the two standard models, but which is not necessarily seen as negative.165

5. THE RELEVANCE OF INSTITUTIONS IN THE ADOPTION OF LEGAL MODELS AND CASE LAW TRANSPLANT

The analysis of constitutional adjudication in developing countries is directly related to their institutional capacity. The main issue that is analyzed is the realization of the rule of law, understood as the existence of limitations on the exercise of public powers and the creation of a public order in the relationships between citizens. The rule of law is supposed to produce certain, predictable and reliable relationships among citizens and with the state, and it is also supposed to limit the discretionary competences of public authorities and to promote economic development.166 An independent judiciary and a "well-developed legal profession" are considered to be crucial for the achievement of the rule of law.167 In developing countries, however, the non-realization of the rule of law is mainly attributed to the lack of political support for the judiciary and its marginalization from politics and the lack of effective mechanisms to enforce rulings, which prevents the achievement of the goals of political and economic actors.168,169 The Economic Analysis of the Law (EAL) approach assumes that poor countries fail to attain the rule of law due to corruption, the lack of resources of the judiciary, and the huge influence of interest groups on the government.170 Traditional approaches to development based on public law should be replaced by a private law approach that minimizes the presence of the state in the economy and decreases the role of regulations and administrative law171 because government employees lack both motivation and information.172 Governments, instead of financing "growth by public policy" should design "a legal framework in which private investors finance growth".173 Based on these hypotheses, this approach proposes some ideas: First, it is cheaper to have good rules than to have good institutions, and therefore the former must be privileged. Second, judicial discretion should also be limited (avoided), privileging regulation through rules over standards or general principles, in order to achieve better performance in adjudication as well as greater control.174 Principled adjudication "require(s) subtle reasoning to arrive at a decision", and the lack of academic background among the civil service and the judiciary in developing countries obstructs the enforcement of regulations. In rich countries the inverse situation is desirable175. Third, the emphasis should be on private law, training of staff, and transplanting laws.176,177 This position is partly reflected in the advice given by Multilateral Organisms such as the World Bank and the IMF.178

Judicial adjudication of ESC rights is a complex issue in the implementation of development policies. The rules on the implementation of constitutional rights in developing countries, particularly in Latin America, were studied from the perspective of the (normative) Public Choice approach.179 The analysis of ESC rights is especially relevant because it has caused major controversies in constitutional adjudication, even more so in countries where the rights discourse is politically important.180 In general it recommends that the number of recipients of subsidies should be inversely proportional to the burden on the taxpayers and thus, the list of entitlements strongly depends on this relationship; in poor countries "a short list of rights seems optimal" because the optimal set of rights depends on the country's conditions in terms of "income level and the degree of empathy its citizens feel for one another".181 As a result, these countries are expected to find a constitution and institutions "that complement and reinforce one another".182 The EAL in Latin America also opposes aspirational constitutionalism and supports restrictive constitutionalism, leaving ESC rights in the sphere of the legislator.183 This approach therefore rejects judicial discretion and the subsequent use of the balancing method used by the judiciary to protect constitutional rights, because of the lack of institutional capacity. In contrast, some studies show that modern Latin American constitutions are generally very long and detailed, which complicates comparison,184 and include a vast number of social rights.185 The reforms generally failed due to the lack of capacity to transform the structures of power186 and therefore, the challenges are not "whether constitutions should be judicially enforced, but how constitutions become entrenched against political inroads".187 Another characteristic, the "intense constitutional experimentation" to empower courts and constitutions, reflects the "global expansion of the judicial power" seeking to push democratic transformations in developing countries. Opponents consider that this empowerment has a negative effect on citizens' respect for the constitution and their confidence in the competence of legislators to solve "pressing problems".188

In the same sense, a sociological approach considers that judicial adjudication that takes into account social policies and seeks redistributive policies does not necessarily improve the situation of poorer citizens. A social conservative but instrumentalist judiciary may be more dangerous than a judiciary that applies the law mechanically189 When a legal system promotes "sensible adjudication", i.e. the judiciary is asked to respond to social needs, it becomes "charismatic" because judges are supposed to harmonize competing social and governmental interests and to promote democracy, although they do not have special capacities to change the rules.190 Their use of citations is seen as a way to maintain their charismatic power, because when textual restrictions disappear, judges may use their personal views on social needs and take positions on political, economic and social issues. As a result, other branches may decide to nominate justices of the same political party, a situation that is particularly dangerous in developing countries where social and economic issues are more prevalent.191 In addition, the tendency in many developing countries is to adopt "ideal" norms that are impossible to enforce but easy to promote in an open interpretation of the constitution.192

The political legitimacy (in terms of independence and impartiality) of constitutional courts in Latin America is also threatened by the strong influence of private and political loyalties. The main problems of the judiciary in the region were summarized as follows: (i) the selection of judges is normally discretional and the dismissal through impeachment is frequently a "political judgment";193,194 (ii) constitutionalism has not been independent from politics, and the enforcement of constitutional guarantees may be threatened by political pressure;195 (iii) other political powers lack institutional capacity;196 (iv) the gap between law in books and law in action is bigger in Latin America than in other legal orders. Although the constitutions were inspired by the US model, the gap between written constitutions and reality depends also on the social context and on the elites' respect for the constitution. Simply copying an institution does not guarantee results because it can be transformed.197

Despite these critics, and the fact that judicial independence in Latin America has traditionally been considered to be weak,198 other arguments hold that the judiciary has been reforming and increasing its institutional relevance, with the assistance of international cooperation. As a result, "formal judicial independence" has been achieved through constitutional and legal reforms, referring basically to: (i) the creation of constitutional courts and counsels of the judicature (for internal management of the branch), and (ii) the reform of the appointment procedure, the judicial career path and the budget.199 The judiciary is also an institution that may benefit from disputes between the legislative and the executive and therefore, its role in the "internationally-recognized norms of human dignity" is justified.200 Further, Latin American Constitutional Courts are also perceived as capitalizing on the fragmentation of the political system, despite the variety of models of constitutional adjudication present in the region.201

CONCLUSIONS

The article aimed to review (mainly) international and (selected) national literature on judicial review and constitutional adjudication to contextualize the case of the Colombian Constitutional Court. The aim was not to evaluate the quality of the Court's adjudication or to advocate for or against any specific position regarding the Court. This literature review suggests that, contrary to what is often affirmed, the case of Colombia is perhaps not as 'exotic' or 'avant-garde' as is sometimes claimed. It corresponds to a global trend that is not closely identifiable with a specific country model, leading to similar criticisms of imported constitutional adjudication as those raised in other (developing) countries. After twenty years of existence of the P.C., the challenge is not to obstruct the application of global trends in constitutional adjudication through case law transplant, or to defend or attack a specific method of adjudication, which is generally accepted as a discretionary competence of the judiciary. The challenge is rather about how to improve the institutional capacities of the judiciary and -logically- of the legislative and the executive, because good laws are as important as good rulings. The literature on the institutional capacity of the judiciary is not an attack on the role of the judiciary, but rather a demonstration of some failures that cannot be ignored. This is again a problem which is shared with other (developing) countries.

FOOTNOTES

1 Ramos Romeu, F. , "The Establishment of Constitutional Courts: A Study of 128 Democratic Constitutions", Review of Law and Economics, 2006, 2, (1), p. 103.

2 On the history of constitutional control in Colombia, see also Charry Urueña, J. M., Justicia constitucional. Derecho comparado y colombiano, Colección Bibliográfica Banco de la República, Bogotá, 1993; and Cepeda Espinosa, M. J., "Judicial activism in a violent context: The origin, role, and impact of the Colombian Constitutional Court", Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 2004b, 3, (special issue).

3 Palacios Mejía, H., "El control constitucional en el trópico", Precedente 2001, Anuario Jurídico Facultad de Derecho y Humanidades, Universidad ICESI, Cali, 2001, pp. 3-19. Cepeda Espinosa, "Judicial activism...", op. cit.; Schor, 2008; Conesa, L., The Tropicalization of Proportionality Balancing: The Colombian and Mexican Examples, Cornell Law School LL.M., Paper Series N° 13, 2008; Restrepo, E., "Constitutional Reform and Social Progress: The Constitutionalization of Daily life in Colombia", paper presented in SELA: Seminario en Latinoamérica de Teoría Política y Constitucional, Yale Law School, 2002, in <http://www.law.yale.edu/documents/pdf/Constitutional_reform_and_social_progress.pdf>; Restrepo Amariles, D., "Los límites argumentativos de la Corte Constitucional colombiana a la luz de la teoría de Toulmin: el caso de la 'unión marital de hecho' de las parejas homosexuales", Revista Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Políticas, 2008, 38, (108), pp. 421-451; Clavijo, S., "Fallos y fallas económicas de las altas cortes: el caso de Colombia 1991-2000", Revista de Derecho Público, 2001, (12), pp. 27-66; Clavijo, S., Descifrando la "nueva" Corte Constitucional, Libros de Cambio Alfaomega Colombiana S.A., 2004a; Uprimny Yepes, R. & García Villegas, M., "The Constitutional Court and Social Emancipation in Colombia", in De Sousa Santos, B. Democratizing Democracy: Beyond the Liberal Democratic Canon (Reinventing Social Emancipation: Towards New Manifestos), 2001, in <http://www.ces.uc.pt/emancipa/research/en/ft/justconst.html> visited on 1st August 2008; Uprimny Yepes, R. & Rodríguez Garavito, C., "Constitución y modelo económico en Colombia: hacia una discusión productiva entre economía y derecho", Documentos de Discusión N° 2 de Justicia, Bogotá, 2006.

4 Palacios Mejía, "El control...", ibid., p. 7; Kugler, M. & Rosenthal, H., Checks and balances: an assessment of the institutional separation of political powers in Colombia. Institutional Reforms, the Case of Colombia, MIT Press, 2005, pp. 76-102.

5 Cepeda Espinosa, "Judicial activism...", op. cit., pp. 565-566. In this view, a ruling may be classified as (i) 'interpretative', when it "determines the meaning that should be given to a particular legal provision (...) or restricts the scope of application or the content of regulations (...)", (ii) 'expressly integrative', when it "expands the law's scope of application to new subjects, situations or things not initially foreseen", i.e. the case of legislative omission in which it applies directly the P.C., and (iii) 'materially expansive decisions' which are "all the different types of decision that do not fall under the other categories, but which the Court has nevertheless adopted since 1992 (...)". Cepeda Espinosa, ibid., p. 566.

6 Cepeda Espinosa, ibid.

7 Palacios Mejía, "El control...", ibid., p. 7; López Medina, D. E., El derecho de los jueces, Editorial Legis, Bogotá, 2000, p. 33.

8 López Medina, D. E., Teoría impura del derecho: la transformación de la cultura jurídica latinoamericana, Universidad de los Andes, Universidad Nacional de Colombia y Legis, Bogotá, 2004, pp. 104-108.

9 López Medina, D. E., Interpretación constitucional, 2ª ed., Consejo Superior de la Judicatura - Sala Administrativa, Escuela Judicial Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, 2006.

10 The analysis of precedents, although relevant, is not further analyzed due to space constraints.

11 Mattei 1988, quoted by Fon and Parisi in: Fon, V. & Parisi, F. , "Judicial Precedents in Civil Law Systems: a Dynamic Analysis", Law and Economics Working, Paper Series 04-15, George Mason University School of Law, 2004.

12 Fon & Parisi, ibid.

13 Ibid.; Schneider, M., Judges and Institutional Change: An Empirical Case Study, Institute for Labor Law and Industrial Relations in the EC, 2001, in <www.isnie.org/ISNIE01/Papers01/schneider.pdf>.

14 Buscaglia, E., "Análisis económico de las fuentes del derecho y de reformas judiciales en países en desarrollo", en Roemer, A. (comp.), Felicidad: un enfoque de derecho y economía, UNAM Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, Themis - Revista de Derecho, 2005a, pp. 295-321, en <http://www.bibliojuridica.org/libros/4/1637/pl1637.htm>.

15 In Latin America the conflict between judicial and legislative interpretation (through interpretative laws that may be struck down) has highlighted the conflict between the two powers with political implications; some cases of impeachment in Argentina are quoted as examples. Sagüés, N. P. , "Desafíos de la jurisdicción constitucional en América Latina", ponencia en el Seminario de Derecho Procesal Constitucional, Quito, 2004, pp. 25-27, en <http://www.uc3m.es/uc3m/inst/MGP/FCINNPS.pdf>.

16 Arrañuda, B. & Andonova, V., "Judges' Cognition and Market Order", Review of Law and Economics, 2008, 4, (2), pp. 665-692.

17 Posner, R., "Legal Pragmatism", Metaphilosophy, 2004c, 35, (1-2), pp. 157-159.

18 López Medina, Teoría impura..., op. cit.; Kennedy, D., "Three Globalizations of Law and Legal Thought: 1850-2000", in Trubek, D. M. & Santos, A. (eds.), The New Law and Development: A Critical Appraisal, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 23.

19 Three waves of globalization of legal thought have been broadly identified: German hegemony in the second half of the 19th century, French hegemony in the first part of the 20th century, and US hegemony after that. Kennedy, ibid.

20 Judicial review in the US is defined as "the power of any court to hold unconstitutional and hence unenforceable any law, any official action based on a law, or any other action by a public official that it deems -upon careful, normally painstaking, reflection and in line with the canons of the taught tradition of the law as well as judicial self-restraint- to be in conflict with the basic law- in the United States, its Constitution". Abraham, H. J., The Judicial Process, 7th ed., Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 300.

21 Prieto Sanchis, L., "Tribunal constitucional y positivismo jurídico", DOXA, 2000, (23), pp. 161-195.

22 Ramos Romeu, "The Establishment...", op. cit., pp. 104-135; López Medina, Teoría impura..., op. cit.; Kennedy, "Three Globalizations...", op. cit., pp. 19-73.

23 Ginsburg, "The Global Spread...", op. cit.

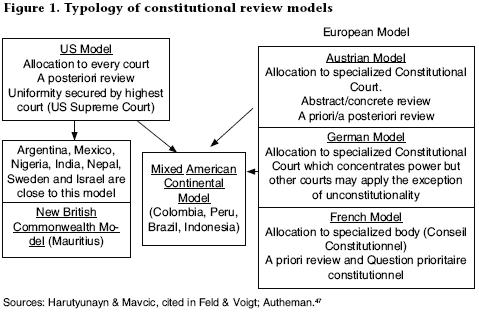

24 See figure 1 for a graphic presentation of the different models and their interrelationships.

25 Schor, M., "Mapping Comparative Judicial Review" (May 27, 2007), Suffolk University Law School Research Paper N° 07-24, CLPE Research Paper N° 3/2007, Washington University Global Legal Studies Law Review, 2008a, 7, pp. 259-263, in <http://ssrn.com/abstract=988848>.

26 Autheman, V., "Global lessons learned: Constitutional Courts, Judicial Independence and the rule of law", IFES Rule of Law White Paper Series - IFES-USAID, 2004, in <http://www.ifes.org/publication/b16a9e8de58c95b427b29472b1eca130/WhitePaper_4_FINAL.pdf>, pp. 2 and 3.

27 Ibid.

28 Prieto Sanchis, "Tribunal constitucional...", op. cit., pp. 172-173.

29 According to this position, the rejection of the myth of the rational legislator through the creation of judicial review has contributed to the expansion of the US system. López Medina, Interpretación constitucional, op. cit., p. 38.

30 Kennedy, "Three Globalizations...", op. cit., pp. 69-70.

31 Ginsburg, "The Global Spread...", op. cit.

32 Tushnet, M. V., "Weak Courts?", Strong Rights/Judicial Review and Social Welfare Rights in Comparative Constitutional Law, Princeton University Press, 2008a, p. 20; Schor, M., "Mapping Comparative...", op. cit., pp. 265-266 Grey, T. C., "Judicial Review and Legal Pragmatism", Wake Forest Law Review, May 2003, p. 7, in <http://ssrn.com/abstract=390460> or <DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.390460>.

33 Schor, M., "Mapping Comparative...", ibid., pp. 287; Epstein, L.; Knight, J. & Shvetsova, O., "The Role of Constitutional Courts in the Establishment and Maintenance of Democratic Systems of Government", Law & Society Review, 2001, 35, (1), pp. 117-64.

34 Wessel 1952:164 quoted by Bazan. Bazan, V., "Neoconstitucionalismo e inconstitucionalidad por omisión", Revista Derecho de Estado, 2007, 20, p. 125.

35 Tushnet, "Weak Courts?", op. cit., p. 156.

36 Bazan, "Neoconstitucionalismo...", op. cit., pp. 136-139. Legislative omissions have been classified as 'absolute' when a constitutional regulation was not developed by the law and as 'relative' when a statute favors some people or groups and excludes others, thus violating the right to equality. Fernández Rodríguez, J. J., La inconstitucionalidad por omisión. Teoría general. Derecho comparado. El caso español, Civitas, Madrid, 1998, p. 116, quoted by Bazan, ibid., p. 140.

37 Bazan, ibid., p. 127; Ginsburg, T., "Beyond Judicial Review: Ancillary Powers of Constitutional Courts", in Ginsburg, T. & Kagan, R. A. (eds.), Institutions and Public Law: Comparative Perspectives, Peter Lang Publishing, N Y, 2004, p. 232.

38 Bazan, ibid.; Tushnet, "Weak Courts?", op. cit., p. 155.

39 Tushnet, ibid., p. 18; Ginsburg, "The Global Spread...", op. cit.

40 Grey, "Judicial Review...", op. cit., p. 7.

41 Ginsburg, "Beyond Judicial...", op. cit., pp. 225-244.

42 Ginsburg, "The Global Spread...", op. cit.

43 Ginsburg, "Beyond Judicial...", op. cit., pp. 226-229. The case of the référé législatif, in which the judiciary sends interpretative questions to the Legislative, was suspended in France in 1837, because it caused uncertainty and because of the perceived "political character" of the decisions, see: Mazeaud, J. & Chabas, F. , Leçons de Droit Civil, 12th ed., 2000, t. 1, p. 167, quoted by Germain, C. M., "Approaches to Statutory Interpretation and Legislative History in France", Duke Journal of Comparative & International Law, Summer 2003, 13, (3), in <http://ssrn.com/abstract=471244orDOI:10.2139/ssrn.471244>, p. 197; Frydman, B., "L'Evolution des Critères et des Modes de Contrôle de la Qualité des Décisions de Justice", Série des Working Papers du Centre Perelman de Philosophie du Droit, Centre Perelman de Philosophie du Droit, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 2007, 4, p. 5.

44 Horn, H. R., "Jueces versus diputados: sistema americano y austríaco de la revisión judicial", Anuario Iberoamericano de Justicia Constitucional, 2002, (6), pp. 223-224; Stone 1992 quoted by Ginsburg in: Ginsburg, "The Global Spread...", op. cit.

45 See Conseil Constitutionnel 2011: 1-3.

46 Stone Sweet, A., "The Politics of Constitutional Review in France and Europe", I.CON, 2007, 5, (69), p. 71.

47 Harutyunayn, G. & Mavcic, A., Constitutional Review and Its Development in the Modern World (A Comparative Constitutional Analysis), Yerevan and Ljubljana, 1999; Feld, L. P. & Voigt, S., "Making Judges Independent - Some Proposals Regarding The Judiciary", CESIFO Working Paper (1260), 2004; Autheman, "Global lessons...", op. cit., pp. 3-4.

48 Schor, "Mapping Comparative...", op. cit., p. 273; Grey, "Judicial Review...", op. cit.; Ramos Romeu, "The Establishment...", op. cit., p. 103.

49 Ramos Romeu, ibid., p. 122.

50 Klug, H., Constituting Democracy: Law, Globalism, and South Africa's Political Reconstruction, Cambridge University Press, 2000; Schor, "Mapping Comparative...", op. cit., p. 269.

51 Hammergren, L., "Fifteen Years of Judicial Reform in Latin America: Where We Are and Why We Haven't Made More Progress", Working Paper, USAID Global Center for Democracy and Governance, 1998.

52 Fix-Zamudio, H., "La justicia constitucional latinoamericana", en Soberanes Fernández, J. S. (comp.), Tendencias actuales del derecho, 2ª ed., UNAM-Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, 2001, pp. 282-297, en <http://www.bibliojuridica.org/libros/3/1376/28.pdf> consulta del 15 de septiembre de 2008, p. 284.

53 Tushnet, "Weak Courts?", op. cit., p. 10.

54 Ibid., p. 15.

55 Grey, "Judicial Review...", op. cit.

56 Kennedy, "Three Globalizations...", op. cit., p. 64.

57 Ibid., pp. 65-66.

58 Gray, D., "Why Justice Scalia Should be a Constitutional Comparativist... Sometimos", Standford Law Review, 2007, 59, pp. 5-6.

59 Gray, ibid., pp. 11-15; for a brief presentation of the US Supreme Court in the 20th century, see Friedman, B., "The Importance of Being Positive: The Nature and Function of Judicial Review", University of Cincinnati Law Review, 2004, 72, p. 1257, in <http://ssrn.com/abstract=632462>.

60 Kochan, D. J., "Sovereignty and the American Courts at the Cocktail Party of International Law: the Dangers of Domestic Judicial Invocations of Foreign and International Law", Fordham International Law Journal, 2006, (29), pp. 542-544; Posner, "The Supreme Court...", op. cit.

61 Ibid., pp. 509, 541-551.

62 Posner, "The Supreme Court...", op. cit.

63 Ackerman, B., "The Rise of World Constitutionalism", University of Virginia Law Review, 1997, 83, p. 772.

64 Lollini, A., "Legal Argumentation Based on Foreign Law an Example from Case Law of the South African Constitutional Court", Utrecht Law Review, 2007, 3, (1), pp. 72-73.

65 Oquendo, A. R., "The solitude of Latin America: the stuggle for rights south of the border", Texas International Law Journal, back issues from April 2008, in <http://www.highbeam.com/Texas+International+Law+Journal/publications.aspx?date=200804>; Schor, "Mapping Comparative...", op. cit., p. 281.

66 Herdegen, M., "La Corte Constitucional en la relojería del Estado de derecho", en Sanín Restrepo, R. (coord.), Justicia constitucional: el rol de la Corte Constitucional en el Estado contemporáneo, 2006a, pp. 71-76.

67 Eskridge, W. N., "The Dynamic Theorization of Statutory Interpretation", Issues in Legal Scholarship: Dynamic Statutory Interpretation Article 16, The Berkeley University Press, 2002, pp. 38-39.

68 Posner, "The Supreme Court...", op. cit., p. 85.

69 Bomhoff, J., "Balancing, the Global and the Local: Judicial Balancing as a Problematic Topic in Comparative (Constitutional) Law", Hastings International and Comparative Law Review, 2008, 31, (2), in <http://ssrn.com/abstract=1184843>.

70 Stone Sweet, A. & Mathews, J., "Proportionality, Balancing and Global Constitutionalism", Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, 2008, 47, in <http://works.bepress.com/alec_stone_sweet/11/>, p. 161.

71 Bomhoff, "Balancing...", op. cit., pp. 8-17.

72 Kennedy, "Three Globalizations...", op. cit., pp. 19-73; Bomhoff, "Balancing...", op. cit.

73 Stack, K., "The Divergence of Constitutional and Statutory Interpretation", University of Colorado Law Review, 2004, 75, (1), in <http://ssrn.com/abstract=518162>; Gargarella, R., "La dificultad de defender el control judicial de las leyes", Isonomía, 1997, (6), pp. 55-70; Iglesias Vila, M., "Los conceptos esencialmente controvertidos en la interpretación constitucional", DOXA, 2000, 23, pp. 77-104, Biblioteca Cervantes; Marmor, A., "Constitutional interpretation", Public Policy Research Papers Series University of Southern California Law School, 2004, (04-4); Ruiz, M. A., "Modelo americano y modelo europeo de justicia constitucional", DOXA, 2000, (23), pp. 145-160, en <www.cervantesvirtual.com>; Cea Egaña, "Estado constitucional de derecho, nuevo paradigma jurídico", Anuario de Derecho Constitucional Latinoamericano, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., 2005.

74 García Amado, J. A., "La filosofía del derecho de Habermas y Luhmann", Serie Teoría Jurídica, Universidad Externado de Colombia, 1997, (5), p. 67.

75 Bomhoff, "Balancing...", op. cit., pp. 8-17.

76 Stone & Mathews, "Proportionality...", op. cit., pp. 74-75.

77 Bomhoff, "Balancing...", op. cit., pp. 31-33; see also Tushnet, "Weak Courts?", op. cit.

78 Vigo, R., "Balance de la teoría jurídica de discursiva de Robert Alexy", DOXA, 2003, 26, pp. 220-221.

79 Tushnet, M. V., "The Inevitable Globalization of Constitutional Law", Harvard Public Law Working Paper N° 09-06, Hague Institute for the Internationalization of Law, 2008b, in <http://ssrn.com/abstract=1317766>, p. 17.

80 Bomhoff, "Balancing...", op. cit., 2008, pp. 5-6.

81 The French case continues to be exceptional because traditional methods of interpretation (the exegetic, the social purpose and the free scientific method) and the classification of "grammatical, logical, historical and teleological interpretations" are dominant (Carbonnier 1979:177; David 1960:140-6, quoted by Germain 2003:197-201). The method of Gény did not have a widespread acceptance in France (Germain 2003:201). Rulings are very short and "do not explain the policy decisions made and the reasoning that led the judge(s) to arrive at a certain result". Policy reasons are in the recommendations (conclusions) presented by the party representing the state, see: Germain, "Approaches...", op. cit., pp. 202-203. The case law referring to the "question prioritaire de constitutionnalité" is too recent to be systematically analyzed.

82 Stone & Mathews, "Proportionality...", op. cit., pp. 74-75, 139-160, in <http://works.bepress.com/alec_stone_sweet/11/>.

83 Tushnet, "The Inevitable...", op. cit.

84 Ibid., pp. 18-20.

85 López Medina, Teoría impura..., op. cit., pp. 34-37; Kennedy, D., "Prólogo", en López Medina, ibid., p. XVIII.

86 On the receptivity to the theories of Kelsen in Colombia, see López Medina, ibid., pp. 341-398.

87 Kunz, J., Latin America Legal Philosophy, 20th Century Legal Philosophy Series, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1948, quoted by López Medina, op. cit., p. 26.

88 López Medina, ibid., pp. 34-37.

89 Fix-Zamudio, "La justicia...", op. cit., p. 293.

90 The principle was first recognized in the Latin American Congress of Constitutional Law in 1975 where its adoption by the Constitutional Tribunal of Argentina was presented; its source was the "recourse de déviation de pouvoir" of the case law of the French Council of State. Fix-Zamudio, "La justicia...", op. cit., p. 293.

91 Conesa, The Tropicalization..., op. cit., p. 2.

92 These countries were chosen because Mexico has a traditional background whereas Colombia is considered the most progressive in Latin America. Conesa, ibid., pp. 1-2.

93 Ibid., p. 16.

94 Fix-Zamudio, "La justicia...", op. cit., p. 283; Mueller, D., "Fundamental issues in constitutional reform: with special reference to Latin America and the United States", Constitutional Political Economy, 1999, 10, pp. 119-120; Schor, M., "Constitutionalism through the Looking Glass of Latin America", Texas International Law Journal, 2006a, 41, pp. 7-11; Schor, "Mapping Comparative...", op. cit., pp. 257-287; Horn, "Jueces...", op. cit., p. 223.

95 Dissenting and concurring opinions are supposed to seek to detract "from the intrinsic value of the precedent", Schaefer, W. V., "Precedent and Policy: Judicial Opinions and Decision Making", in O'Brien, D. M. (ed.), Judges on Judging: Views from the Bench, CQ Press, Washington, 2004, p. 109, because they may be seen as a way to undermine the authority of the ruling, Abraham, The Judicial..., op. cit., pp. 222 y 225. On the opinions of justices, see also Schaefer, ibid., p. 109.

96 Oltra, J., América para los no americanos: introducción al estudio de las instituciones políticas de los Estados Unidos, EUB SL, Barcelona, 1996, p. 159.

97 Elhauge, E. R., "Does Interest Group Theory Justify More Intrusive Judicial Review?", HeinOnline 101 Yale Law Journal, 1991-1992, p. 78.

98 Abraham, The Judicial..., op. cit., pp. 260, 263.

99 Campbell v. Swasey, 12 Ind. 70 (1859) at 72 quoted by Abraham, The Judicial..., op. cit., p. 259.

100 Posner, "The Supreme Court...", op. cit., p. 35.

101 Abraham, The Judicial..., op. cit., pp. 263-268; Posner, R., "Against Constitutional Theory", in O'Brien, Judges..., op. cit., pp. 216-224.

102 Posner, R. & Landes, W. "Legal Precedent: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis", NBER Working Paper Series N° 146, Center for Economic Analysis of Human Behavior and Social Institutions, National Bureau of Economic Research INC., 1976, p. 68.

103 Posner, "The Supreme Court...", op. cit., p. 35.

104 Tushnet, "Weak Courts?", op. cit., pp. 94-95; Oltra, América..., op. cit., p. 159.

105 Abraham, The Judicial..., op. cit., p. 309.

106 Horn, "Jueces...", op. cit., pp. 234-235.

107 Ibid., p. 237.

108 Ruiz, "Modelo americano...", op. cit., p. 149.

109 Horn, "Jueces...", op. cit., p. 237.

110 The constitutional case law of the Supreme Court was considered to be too formal, to erode the protection of rights, and to increase the distance between constitutional rules and reality. Cepeda, "Judicial...", op. cit., quoted by Schor in: Schor, M., "An essay on the emergence of Constitutional Courts: the cases of Mexico and Colombia", Legal Studies Research Papers Series, Suffolk University Law School, September 11 2008b, pp. 1-3. Moreover, it did not allow the legal enfocement of rights. It was based on the French model and the aim of judicial review was not the defense of fundamental rights, López Medina, Interpretación constitucional, op. cit., p. 6. For an analysis of the profiles of justices, their personal ideology and their rulings, see: Grupo de Derecho de Interés Público (GDIP), El magistrado Monroy Cabra: entre el conservadurismo cultural y la solidaridad social, Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de los Andes, 2007, en <http://www.semana.com/documents/Doc-1480_2007724.pdf>.

111 See Landau, D., "The Two Discourses in Colombian Constitutional Jurisprudence: a New Approach to modeling Judicial Behavior in Latin America", George Washington International Law Review, 2005, in <http://www.allbusiness.com/legal/international-law/1023080-1.html> visited on 1st August 2008.

112 Cepeda, "Judicial...", op. cit., quoted by Schor, "An essay...", op. cit., p. 13.

113 Schor, ibid., p. 14.

114 Ibid., p. 15.