Introduction

In the last years, the exponential introduction of digital innovation in the financial space has often generated the observation that Financial Technology (FinTech) is a plausible solution for lowering existing barriers around financial inclusion. One of the main reasons for this argument is the amount of the population worldwide who possess a mobile phone nowadays -78.05 % as of 2020- (Statista, 2021) in comparison to the population with a bank account -69 °% banked and still 1.7 billion persons unbanked1 as of 2017- (World Bank Group [WBG], 2018). The percentage, however, is misleading, as some of these accounts are dormant due to the owner's inactivity.

Studies conducted so far on the potential of FinTech as a financial inclusion tool do not analyze whether the metrics used by the public authorities in charge of implementing financial inclusion strategies and policies are measuring the right concepts efficiently and coherently. For example, if they follow the FinTech impact in the short and long run (for example, FinTech allows reducing transaction costs and incentivizes using the account, decreasing the client churn). In line with these statements, current public studies pivot around the potential for financial inclusion. Still, the metrics probably would not be adequate to address the effectiveness from a broader, long-term point of view, such as human development or financial dignity.

This study focuses on the definition of financial inclusion and the current perspective of FinTech as a financial inclusion tool from a critical position. A more comprehensive approach is proposed, which defines financial dignity as a subcategory of human development. Several financial inclusion policies and metrics from three different jurisdictions in three regions are evaluated, identifying those concepts linked to financial innovation. We will investigate whether they would be suitable for financial inclusion as a short-term target or dignity as a long-term objective. Finally, a proposal structure of key performance indicators related to financial dignity was made.

The Financial Inclusion Concepts

The WBG indicates that "financial inclusion means that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs -transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance- delivered in a responsible and sustainable way" (WBG, 2022). This exact definition is followed by Brummer and Yadav (2019) to link financial inclusion with technological innovations with impact on the financial markets space. In this regard, digitalization has been identified as an enabler for closing the gap of the underbanked population -the G20 High-Level Principles for Digital Financial Inclusion (Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, 2016). This document, considered an evolution of the previous G20 Principles for Innovative Financial Inclusion issued in 2010, built a minimum framework for using technological developments to benefit the underbanked or non-banked populations (Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, 2010).

The OCDE/INFE (2018) enhanced the WBG'S definition adding new key components. A more holistic approach is taken moving towards a broader concept of financial wellbeing: "Financial inclusion refers to the process of promoting affordable, timely and adequate access to regulated financial products and services and broadening their use by all segments of society through the implementation of tailored existing and innovative approaches, including financial awareness and education, with a view to promote financial wellbeing as well as economic and social inclusion".

This expanded definition has been used by several institutions, such as the Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina or the Alliance for Financial Inclusion (2010). In both cases, the financial inclusion definition was enriched by adding different dimensions: i) access, ii) usage, iii) product and service quality, and iv) welfare (CAF-Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina, 2020).

The access concept refers to the possibility of the non-banked population to contract basic financial products (mainly opening a bank account, having credit approved or being able to have a pension plan) adapted to their needs and at a reasonable price. It has to be taken into account that non-banked collectives include people who do not need financial services or do not wish to use them (lack of trust) and those who need or whish but cannot access financial services (Yoshino & Morgan, 2016).

The second element (usage) refers to how often and regularly the product is used and the awareness about it. It is an essential element not usually taken into consideration. As previously mentioned, if the accounts opened to the vulnerable public are not used afterward because they ignore the mechanic or are unfamiliar with new technologies, it could not be considered successful for the cause. At this point, a differentiation between the unbanked and underbanked should be made. The target of reducing the number of populations without a current account may be addressed via the access concepts and corresponding metrics. However, the usage already tries to tackle a barrier at a different level: the population with a current account who is not using it because they ignore the mechanics of the product, mistrust banks or the service does not fit with their situation (e. g, too expensive). Regarding the product and service quality, the requirement is that the offer matches the needs or expectations of the public, generating users' engagement towards the products, as it is considered fit and proper for them (Alliance for Financial Inclusion, 2010).

Finally, as the last step in the evolution of financial inclusion, the financial welfare concept entails achieving financial stability. At this stage, the users can manage their financial situations, including cashflow crises and set targets. This level includes the impact that the usage of financial services has had on their consumers - e. g, entrepreneurship, studies, or health- (Alliance for Financial Inclusion, 2010).

This order access-usage-quality-welfare is also related to the short-term versus long-term impact and the difficulty of obtaining adequate metrics to evaluate each concept. Moreover, all are steps towards individual economic prosperity, understood as "means to enriching lives of people" (Sen, 1990, p. 42). Yet, it is not mapped how those steps support the prosperity of the society in the relevant jurisdiction.

Lights and Shadows of FinTech as a Financial Inclusion Enabler

FinTech has been recognized as a required element for financial inclusion and alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (Arner et al., 2020). These new technologies impact the current public policy frameworks, often translated into regulatory initiatives or even the redesign of the financial system structures in favor of tools to close the financial inclusion gap (Arner et al., 2020, p. 8). Digital innovation can be from the private side (vulnerable populations, small-medium sized enterprises) and the public side (authorities in charge of financial inclusion strategies and their measurement). Therefore, a differentiation should be made at both levels.

Private Side

As mentioned, financial technology has been recognized as a potential tool for financial inclusion. It has also raised consumer protection, data governance, and financial crime management concerns. The new technologies can help individuals hold funds electronically, making managing their finances easier and avoiding being attacked or robbed. Also, digital solutions have proven efficient in archipelagic countries or remote locations where physical reach barriers are tangible (Yoshino & Morgan, 2016, p. 8).

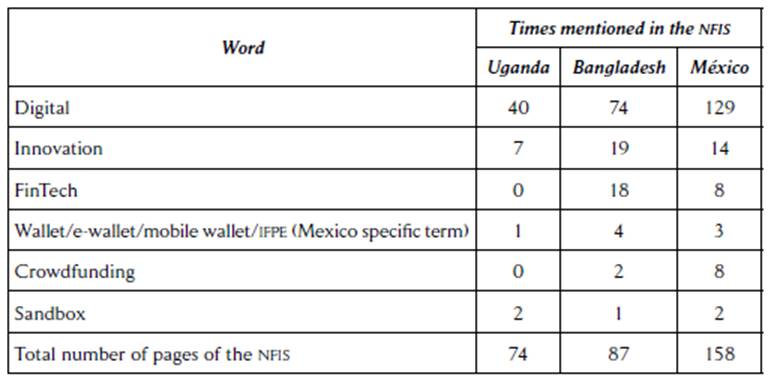

The FinTech concept is broad. It includes a heterogeneous ecosystem that needs to be analyzed to identify which critical points of financial innovations can truly support financial inclusion and which level of the user's needs. Moreover, a distinction should be made among i) traditional finance products (e. g, accounts, cards, loans), ii) products offered by fintech agents under niche strategies or re-bundling of services and iii) products offered in decentralized finance -non-third-party intervention, blockchain-based solutions.

It is true that the financial products identified in Table 1 could be considered enablers for financial inclusion and that they can be linked to the hierarchy of human needs. However, some risks need to be addressed. The first point is the driver behind the FinTech industry and services. As private enterprises offer these solutions, their main goal could be to generate revenue in the shortest period at a minimal cost. This need could be even more vital in the case of FinTech startup firms that must prove early traction of the products (short-term figures) to raise more capital from investors to continue scaling up. That, in turn, may trigger a perverse incentive deviating from the initial message of FinTech firms as social benefactors.

Table 1 Analysis on How the Financial Services Can Serve Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Source: the author.

The second risk concerns the lack of regulatory frameworks or legal certainty versus cost reduction. Traditional financial entities are criticized for their fees to their users, which are linked to the institutions' compliance costs. The FinTech and Decentralized Finance (DeFi) models promise a cost reduction, easy use, and time reduction. It should be noted that they may be partially or non-regulated; therefore, funds may not be guaranteed, or the users may face problems in case of claims.

Special mention should be made to the DeFi space, often presented as the solution to end the unbanked problem. Although distributed ledger technologies may enable faster corridors and reduce costs by eliminating third-party providers, it should be noted that they are still far from being an adequate solution for several reasons: i) the wallets are generally presented in English interfaces, and vulnerable populations already have difficulties in even being able to read in their local languages, ii) the tools often require of some technical knowledge, which is not identified in these target segments, and iii) many of the DeFi products are related with highly volatile investments, therefore, not adequate day-to-day necessities.

Public Side

Arner et al. (2020) propose four long-term pillars of the digital financial infrastructure that would support the transformation required for achieving better financial inclusion results: i) Digital identity and electronic know-your-customer procedures (eKYC), ii) open electronic payment systems and payment infrastructures, iii) digital account opening initiatives, and iv) design of digital financial markets infrastructures (p. 19).

The new technologies identified potential for supervision improvement have circled data governance in general (mining, big data, and data analytics). In these cases, the supervisors have seen the innovation as a tool for better data management to assess the progress in the financial inclusion public initiatives. Innovation also supports improvements in information transparency, as it is easier to share with the private sector, the public and academia. This new way of using data has also derived a new public-private interaction. This approach would be based on crowdsourcing ideas for financial inclusion using innovation as a tool. This solution is not new, as there are precedents in the regulatory space of this "contract regulation or incentive-based regulation" that would set up a co-regulatory approach (Dragomir, 2010, pp. 57-59). This new interaction has also been reflected in new public supervision via the regulatory sandbox regimes implemented in several countries around the globe. Regulatory sandboxes allow the private sector to innovate and test models that do not fit within the existing regulatory frames. At the same time, it enables supervisors to assess the potential impact of the new models and address adequate and proportionate control measures. Finally, new technologies and the aim to look for more inclusive solutions have driven the public authorities to the crypto-assets world. In this space, authorities are researching how to issue their central bank digital currencies (CBDC) for a more timely, integrated, and efficient payment infrastructure scheme.

However, there are also identifiable disadvantages or barriers: i) heavy dependency on volatile governments, especially in developing jurisdictions, ii) lack of technical knowledge from the public side combined with a lack of resources fully dedicated to the topic both in terms of independent budget and staffs, and iii) data related issues, such as the quality of the data feed, which private sector agents usually provide, how to maintain the information updated in the long-term, or that new FinTech businesses are not under the supervision radar, and therefore, their data is not used for statistical purposes. Lack of resources and technical knowledge could be tackled via flexible public-private work arrangements to introduce innovations in supervision environments, specifically, as tools to support public financial inclusion initiatives (Rasmussen & Mattern, 2022, p. 2).

One Step Further: Human Dignity and Financial Dignity as Its Logic Outcome

Human dignity is considered the basis of all fundamental rights, as it is indicated in the Preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, by stating "recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world" (European Union Agency of Fundamental Rights, 2007). According to this definition, human dignity is an element of intrinsic value to the person. This idea is aligned with Kant's description of dignity, who considered that all that can be replaced has a price. Nevertheless, those elements that do not have a replacement or that do not have a price belong to the dignity reign, becoming not a mean but an end -human dignity itself as an end- (Kant, 1785).

Human dignity, under this perspective, has several layers. Article 1 of the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) states: "All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social, and cultural development". It is therefore recognized that economic dignity is one facet of human dignity. Article 1 of the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights:

All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social, and cultural development.

All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon the principle of mutual benefit, and international law. In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence (United Nations General Assembly, 1966).

However, financial dignity entails financial capacity -understood as internal financial well-being provided by improving the person's skills, knowledge, and behaviors in this field- and external factors impacting the financial well-being -limiting or boosting it- (Brown, 2020).

Financial capacity (internal well-being) can be impacted by the external factors or structures around the individual that condition their financial well-being (Brown, 2020, p. 9). Those external factors can range from family and friends to authorities, laws, or customs. In this way, these external elements allow the freedom to make informed financial decisions. The central elements of financial well-being can be classified as i) financial literacy, understood as the action of improving knowledge and awareness so individuals can make informed decisions (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011), ii) resilience, iii) capabilities and iv) financial inclusion. Therefore, it is an angle from the whole economic well-being, which focuses on the persons but does not consider the impact on society in general.

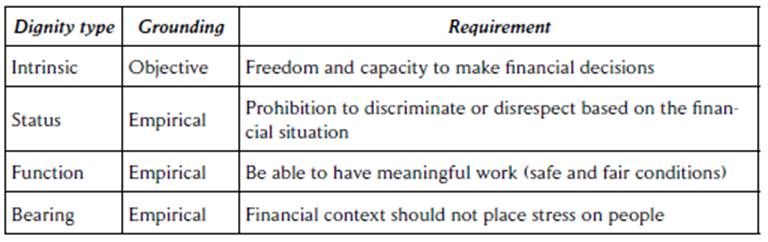

Financial dignity or economic dignity "deals with the dimensions of a person's dignity that are linked to their economic context" (Brown, 2020, p. 11). However, dignity is not purely individual, as it contains social connotations (status). Therefore, it can be said that certain sets of demands should be accomplished depending on the approach taken toward the financial dignity concept (Table 2) (Brown, 2020, p. 16). The intrinsic financial dignity concept has already been analyzed, based on the financial capacity described by Sen. Financial dignity as status is inherited from ancient types where the dignified person was virtuous or excellent (artistos). Therefore, it resulted in a higher level than the rest of society -the aristocrats- (Valls, 2015, p. 285). In the Christian era, this interpretation evolved to equality (all humans equal). Hence, financial dignity under the status perspective would be considered as the prohibition of disrespect based on the financial situations of the person or collectives (Brown, 2020, pp. 11-16). Financial dignity as a function is interpreted as the capacity of a person to perform a work that satisfies them in fair conditions and allows them to fulfill their curiosity. It would include non-paid work such as taking care of ascendants, descendants, or volunteer work (Brown, 2020, pp. 11-16).

Finally, the bearing interpretation is linked with deontological or moral components, as it refers to the right thing to do (Rosen, 2012), even in cases where the decision is "what is the less negative option". These choices imply negative emotions in decision-makers. Consequently, the institutions should try to ease them (Brown, 2020, pp. 11-16). In the financial universe, this would imply that the authorities would need to seek ways to avoid financial distress on the people, especially in specific vulnerable collectives.

Financial Inclusion Strategies in Developing Countries and Tracking Metrics Linked to Financial Technologies

Financial inclusion strategies and policies around the globe have been designed. However, the real challenge is the tactical side: how to implement those policies effectively and what metrics should be designed and followed for extended periods. An adequate measurement of the financial inclusion strategies would allow public authorities to assess their efficiency or the need to enhance or change the approach. Statistics and data analytics also enable supervisors to evaluate the trade-offs between financial stability and innovation (Tissot & Ganadecz, 2017, p. 2).

This section will analyze and evaluate the central performance indicators of three countries on three different continents from several perspectives (based on information publicly available on their web pages). First, the governance structures arrangements around financial inclusion activities, followed by the analysis of whether the financial inclusion strategies and policies in the country refer to innovation-related terms (digital, digitalization, innovation, fintech). Afterward, the metrics used in each country will be analyzed based on the data source, type of inclusion or financial necessity covered, whether it is a short-term or long-term indicator and the potential FinTech that would support or boost those metrics. In the specific case of Mexico, the initiatives related to measuring financial literacy and structural improvements are considered.

Africa: Uganda

The Republic of Uganda published its National Financial Inclusion Strategy in October 2017. The coverage period of the NFIS is from 2017 to 2022. The document was designed by the Bank of Uganda and the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development -MOFPED- (Republic of Uganda, 2017). The NIFS' governance arrangement is based on a coordinated approach between the MOFPED and the Bank of Uganda, which includes the possibility to consult and be supported by the private sector (Republic of Uganda, 2017).

The financial inclusion definition taken in the country includes the concepts of access, usage, and quality -"having access to and using a broad range of quality and affordable financial services which help ensure a person's financial security"- (Bank of Uganda, 2022b). However, the main work is centered on access and usage, as evidenced in the data analysis. The priority work areas reflected in the NIFS are women, youth, and rural populations (Republic of Uganda, 2017, p. 25). Specifically, in the case of rural women above fifteen years, the report shows access to mobile phones and mobile payments are lower compared with men. Women tend to fall under informal economy solutions in these cases, with worse conditions and low scalability opportunities.

Digitalization of the financial markets was identified as one of the principal objectives and pillars of the National Financial Strategy (objective 3: build out the digital infrastructure for efficiency). The initiatives so far have focused on enhancing the mobile money regulatory framework and guidelines and updating the Financial Institutions Act to open the market to new agents. Specifically, due to Uganda's Islamic majority, the initiatives have taken an ethical or religious approach, including Islamic finance-specific frameworks (Bank of Uganda, 2022b).

Under this NFIS, 26 financial inclusion measurement indicators were designed to check the efficiency and progress of the national policies in this area (Republic of Uganda, 2017, pp. 46-47). Most indicators are linked to access and usage, and only two have been identified as quality-related. The NIFS does not determine the welfare level. Moreover, several cases placed under the usage dimension, such as the percentage of adults with at least one regulated deposit or credit account type, would be identified with access rather than usage. All the cases have been identified as short-term and direct metrics, but none look to quantify a broader long-term impact. Finally, although the primary target beneficiaries would be women, youth, and rural populations, only one indicator directly measures the effect on women -the percentage of women with at least one type of regulated deposit account. The same happens in the case of youth-related financial inclusion initiatives -the percentage of youth (15-17 yrs. old) with at least one type of regulated deposit account. No specific mention of the rural populations in the metrics proposed.

Once the NFIS is analyzed, the next step is to evaluate the follow-up of the metrics proposed and whether the progress statistics are transparent and available to the public in general. The information displayed on the Bank of Uganda web page under the financial inclusion indicators (section Data and Statistics) entails 11 metrics under three categories: access points, number of accounts and indicators (Bank of Uganda, 2022a). The information covers the period from 2013 to 2015 on an annual basis and from 2016 to June 2021 on a semi-annual basis. All cases correspond to indicators whose source of information is the supply side and measure elements linked with the physiological needs previously described. Moreover, almost all cases, except one, refer to access elements and can be considered short-term direct metrics. In all cases, the technology associated with e-wallets and digital payments (Pay Tech) could work as an enabler for improving the efficiency of the initiatives.

It must be noted that the available statistics do not meet the financial inclusion measurement indicators included in the NFIS 2017-2022. A 69.23 % of the initially planned indicators could not be directly identified in the follow-up metrics implemented and publicly available. The metrics related to women and youth could not be found in the follow-up metrics implemented by the Bank of Uganda in the financial inclusion statistics. In conclusion, there seems to be a certain level of decoupling from the target beneficiary populations to the economic indicators design and from those to the actual implementation and measurement that is displayed on the web page of the local central bank.

Asia: Bangladesh

The People's Republic of Bangladesh has designed a financial inclusion strategy, published in May 2021. It is the country's first formal NFIS; the previous financial inclusion initiatives were based on the Memorandum of Understanding for th e Business Finance for the Poor in Bangladesh (BFP-B) between the UK government and the Bangladesh government (Ministry of Finance, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh & Bangladesh Bank, 2021, pp. 76-77).

Regarding the governance structure, the NFIS is actioned via three different layers (Ministry of Finance, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh & Bangladesh Bank, 2021, pp. 69-73). The top decision maker is the NFIS National Council (NNC): the Ministry of Finance. This council has over twenty members of different ministries, the central bank, chambers of commerce and associations. It is responsible for the financial inclusion strategy design and oversight. The second lawyer is the NFIS Steering Committee (NSC), chaired by the governor of the Bank of Bangladesh and composed of more than 40 members of different public and private organizations. The Steering Committee ensures proper coordination, effectiveness, and adequate quality control. Finally, the NFIS Administrative Unit (NAU) is a separate department within the Bank of Bangladesh in charge of the day-to-day activities related to financial inclusion.

The financial inclusion definition, in this case, explicitly recognizes technology as a central element in supporting financial inclusion. This position is evidenced in the document (see Annex I). The NFIS defines financial inclusion as: "Access of individuals and businesses including unserved and underserved to the full range of financial services facilitated with technology provided at affordable cost with quality, ease of access and scope of risk mitigation in responsible and sustainable manner through a regulated, transparent, efficient, and competitive financial marketplace" (Ministry of Finance, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh & Bangladesh Bank, 2021, p. 56).

In the case of Bangladesh, innovation is seen as a clear opportunity for financial inclusion: "Adoption of ICT is changing the nature of financial engagement, introducing opportunities for e-commerce, fintech, digital credit which create an opportunity to leapfrog stages of financial development through more intuitive interactive technologies like Blockchain, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), Internet of Things (IOT), Big Data Analytics etc." (Ministry of Finance, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh & Bangladesh Bank, 2021, p. 9).

Innovation has been determinant for regulatory and public policies developed between 2015 and 2020, with numerous plans flourishing,2 translating into the country's inclusion objectives and twelve strategic goals. Several refer to using technology to improve the financial sector infrastructures rather than focusing on particular collectives. Only one of the goals focuses on specific population sets -women, the population affected by climate change, other underserved segments and senior citizens- (Ministry of Finance, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh & Bangladesh Bank, 2021, pp. 62-67). The indicator is directly related to financial literacy enhancement.

The financial inclusion metrics of the country are publicly available, covering the period from December 2018 to December 2021 with a monthly frequency (Central Bank of Bangladesh, 2022). A total of 117 key performance indicators have been identified and classified under the following groups: i) Branch Statistics, ii) ATM, POS, CDM and CRM Statistics, iii) Issued Cards and Transaction Statistics, iv) ATM, POS, CRM and e-Commerce Transaction Statistics by Cards, v) Local and Foreign Currency Transaction Statistics by Cards, vi) Interbank Transaction Statistics, vii) Internet Banking, viii) Mobile Financial Services (MFS) Statistics, ix) Agent Banking Statistics, x) School Banking, and xi) Special Accounts Statistics. These metrics partially cover 5 out of the 12 objectives described in the local NFIS; however, concepts such as insurance services, capital markets or risk management, which are objectives identified, have not been assigned with adequate performance indicators.

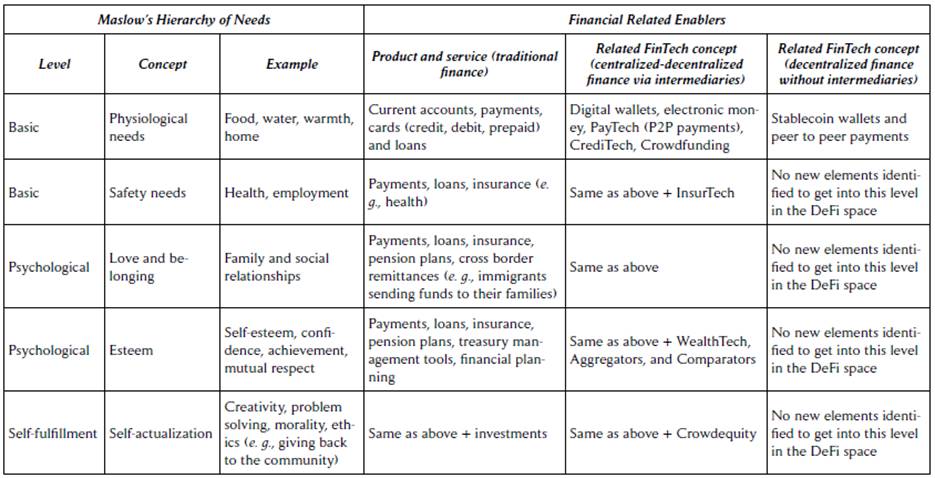

Like in the Uganda case, all indicators have been associated as information provided from the supply side, short-term direct metrics, covering mainly physiological necessities. The publicly available Bangladesh indicators show a more balanced approach to addressing different types of financial inclusion, with a more balanced approach towards access, usage, and quality (Figure 1). Well-being indicators are missing in these metrics as well.

Source: the author.

Figure 1 Classification of Bangladesh Indicators Based on the Four Types of Financial Inclusion

Six cases show an indicator split between male and female (totaling 12 entries). Thirty-one cases refer to urban population data versus rural population data (totaling 62 entries). However, the general objectives do not seem to reflect the importance given to these collectives. The rural population is not explicitly mentioned in the core twelve goals of the NFIS; it is only included in two of the 69 specific targets linked with entrepreneurship and alternative financing schemes (Ministry of Finance, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh & Bangladesh Bank, 2021, pp. 64-67). In summary, like Uganda, specific high-level financial goals do not seem to have continuity in the financial inclusion metrics and statistics available on the Central Bank of Bangladesh web page.

Latin America: Mexico

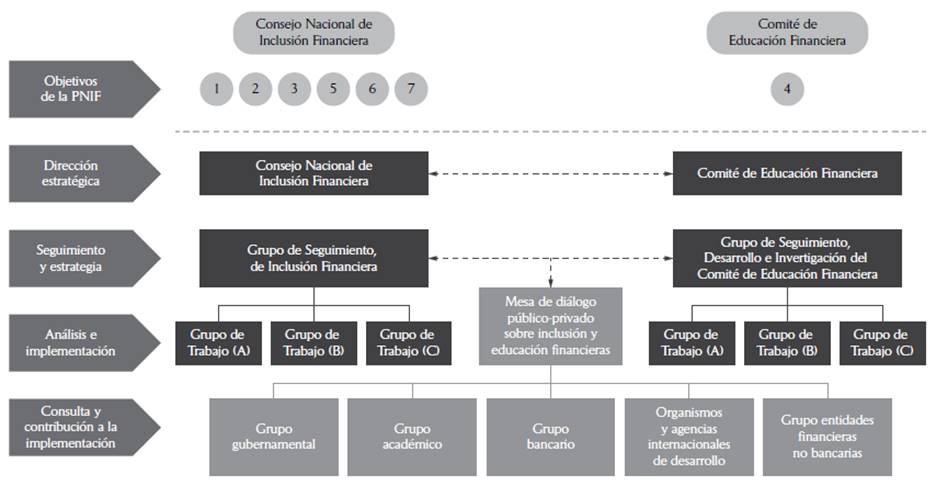

The Mexican Financial Inclusion Policy (PNIF, for its initials in Spanish) was initially published in 2016 and was updated with a new version in March 2020 (Gobierno de México, 2020, p. 13). It is a very detailed document that shows the evolution the country has suffered on this topic. The governance arrangements are split into two main verticals corresponding to the financial inclusion activities and financial education vertical with its operational structure. Like the Bangladesh case, there are strategically related committees (inclusion and education), follow-up groups, and a third layer of working groups focused on analysis and implementation. Mexican governance formally identifies public-private working groups with different contributors (Figure 2).

The Financial Inclusion National Council (Consejo Nacional de Inclusión Financiera) is chaired by the Secretary of the Tax Ministry and composed of members of public financial authorities. This representation is continued in the follow-up and strategic group (Grupo de Seguimiento de Inclusión Financiera). On the other hand, the Financial Education Committee (Comité de Educación Financiera) is chaired by the Sub-secretary of the Tax Ministry and composed of members of public financial authorities and members of public education authorities. As in the financial inclusion case, the follow-up and strategy group (Grupo de Seguimiento, Desarrollo e Investigación del Comité de Educación Financiera) comprises operating members that replicate the representation of the Financial Education Committee.

Regarding the foundational concept for the policy, the Mexican approach goes beyond the traditional financial inclusion policies, as it takes a broader concept as its basis: financial health (salud financiera) defined as "people to be able to manage their finances adequately, allowing them to face their daily expenses, face negative variations in their income flows and disproportionate or unexpected increases in their expenses (have resilience), achieve their goals and take advantage of opportunities to achieve their well-being and economic mobility" (Gobierno de México, 2020, p. 28).

This definition shows a step forward; it already includes concepts such as resilience or financial well-being and economic mobility, which show the aim of the public institutions that their population reaches adequate management and freedom of their financial situation. This definition implicitly aims for long-term targets and an approach towards financial dignity. The technology financial innovation is integrated into the Mexican PNIF as an enabler for the cause and an objective (increase digital payments and improve the financial infrastructures). The potential identified has been supported by the publication of the first Fintech Law of the world in 2018, which recognizes and regulates different types of FinTech models, including Pay Tech and Crowdfunding, among others (Cámara de Diputados, 2021). It allows the supervisors (Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores or CNBV) to capture data from these types of institutions and improve the quality of their metrics.

This PNIF sets up seven high-level objectives, six focused on the market (financial health and literacy) and one expressly set up for information and investigation purposes (Gobierno de México, 2020, pp. 81-99). The policy already advances the principal performance indicators designed and implemented to evaluate the efficiency and progress of the objectives (Gobierno de México, 2020, pp. 123-149). The report's analysis shows the budget allocation to the different initiatives that contribute to the improvement of the financial health in the country from the transparency approach (Gobierno de México, 2020, pp. 113-119).

The logic and transparency of this design have continued in the implementation phase of this policy. The Financial Inclusion National Council set up a dedicated monitoring platform open to the public (Consejo Nacional de Inclusión Financiera, 2022). This platform includes reports, the national inclusion survey results, and all the metrics used to supervise the financial health goals. Seventy-eight indicators were created, and each has been identified as linked to a general objective or operational strategy included in the PNIF.

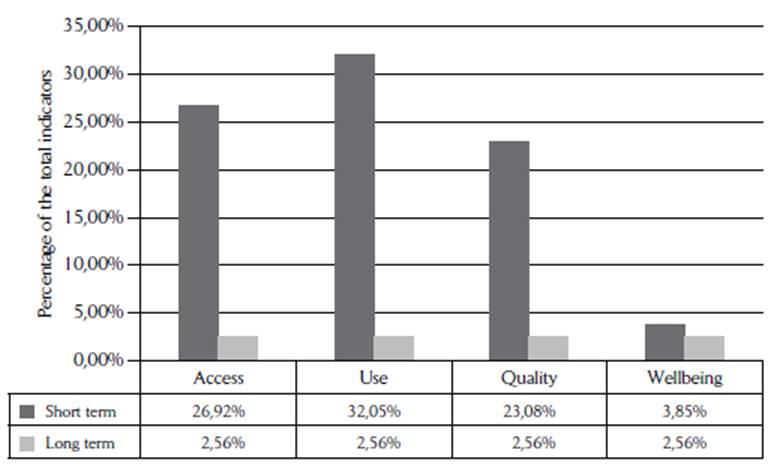

The analysis shows all seven high-level objectives have been assigned with corresponding metrics, and the way to calculate them is openly shared. The monitoring dashboard includes a balanced distribution of the indicators regarding the information's origin (51.28 % from the supply side, 47.72 % from the demand side). It is also reflected in the frequency of the provision of information (triennial or annual). The triennial indicators are related to demand data, which could be due to the cost of the surveys in terms of time, resources, and financing (Tissot & Ganadecz, 2017, p. 6). This broader approach continues to be reflected in the levels of inclusion (several elements identified with quality and well-being). Moreover, including demand source data catalyzes indicators that measure the populations' medium- or long-term plans (Figure 3).

Source: the author.

Figure 3 Classification of México Indicators Based on the Four Types of Financial Inclusion and the Impact Term

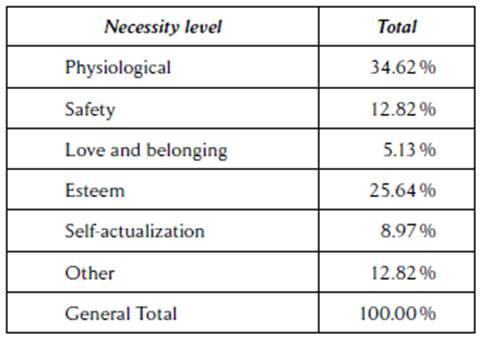

This diversity is also translated into the levels of necessity covered, including physiological or safety needs metrics and love and belonging, self-esteem and self-actualization-related ones (Table 2). Moreover, 12.82 °% of the metrics are related to external structural factors, such as cybersecurity infrastructures, connectivity or information-gathering indicators. Therefore, the Mexican approach seems to have included elements that can strive towards the financial dignity concept, recognizing that other secondary external features can boost or limit the financial health of the Mexican population.

As the Mexican indicators diversify the levels of necessity that they cover, it has been identified that the financial technology that could support these initiatives is more varied compared with the Uganda and Bangladesh cases. Specific references exist to payment technology, crowdfunding, digital identity, or application programming interfaces. Moreover, there is room for comparators (platforms that allow the user to compare financial products), insurance technology (InsurTech), wealth technology (WealthTech) and supervision technology to support several of the indicators analyzed. In this case, the financial infrastructure and the digital and data infrastructure were considered and included, which underpin the provision of financial services and products in general (Tissot & Ganadecz, 2017, p. 3). For example, promoting a digital identity solution would help tackle issues specific to rural areas (Yoshino & Morgan, 2016, p. 20) and the immigrant population.

In short, the Mexican initiative seems to be a comprehensive, well-designed framework that has continued monitoring the metrics and seems to go further than other countries in terms of information integration in one single dashboard -transparency- and incorporates FinTech firms as data sources. Financial innovation is also a structural element that amplifies financial health initiatives.

How to Measure the Impact of FinTech in Financial Dignity

The analysis of Mexico, Uganda, and Bangladesh shows the current financial inclusion metrics focus on immediate tangible results -short-term. Only under the Mexican framework do few cases consider behavioral elements requiring what could be viewed as a medium- or long-term result. Those performance indicators are based on demand data sources and could be biased by the individual's perception. None of the cases' long-term material analyses showed improved financial dignity.

Innovation allows payment digitalization, receiving subsidies efficiently, and improving cross-border transfers, which are vital for most immigrants to support their families in other countries taking access to a digital wallet and electronic payments as an example. From the public perspective, e-wallets reduce the impact time on their targeted populations, and data allows authorities to assess the population's real necessities better. However, these milestones can be identified as direct impacts (what could be called Tier 1 results). There are secondary or indirect impacts on the population that the supervisors do not follow.

Access to subsidies or funds via digital wallet is the immediate result. Yet, the next question is whether the family receiving the funds has improved in different aspects. A case would be to use the funds to improve their literacy levels -for example, girls in the family have attended school or could progress educationally above the average, reducing the risk of being exposed to gender domestic violence. This topic would be associated with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 4 related to education, SDG 5, gender equality and SDG 10, reducing inequalities). A second case could be improving their health, increasing longevity or decreasing premature or infant death. The health-related topics could be linked with UN SDG 3 (good health and wellbeing). Finally, the third case could be housing quality, whether the funds received could help access drinking water, electricity, better energy solutions or improve the materials of the family house. Under this scenario, the initiative would support UN SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation) and SGD 7 (affordable and clean energy).

In the case of small and medium-sized enterprises, the question is whether access to funds via a digital wallet has allowed schools or hospitals better treasury management, reduced payments delays, and enhanced their capacity to plan and invest for improving their services and business. There are indirect metrics applicable from the public sector perspective. For example, implementing electronic or blockchain-based payments would enhance transparency in public administrations to reduce the levels of bribery and corruption in a country (Yoshino & Morgan, 2016, p. 5). These indirect results (that can be denominated as Tier 2 results) are long-term impact metrics that do not seem to be included in the analyzed countries. Mexico has specific long-term metrics related to the capacity of individuals to face adversity, plan, or manage their finances. Still, the financial dignity metrics would entail an impact idea beyond this -it would answer "why" or "how" questions. It means that the authorities in charge of data collection would also need to source the reason behind the data -why the user asked for a loan, how they spent the money, following an approach similar to Toyota's Hansei methodology -identifying the root cause by asking five times why- (Liker, 2006, pp. 379-389).

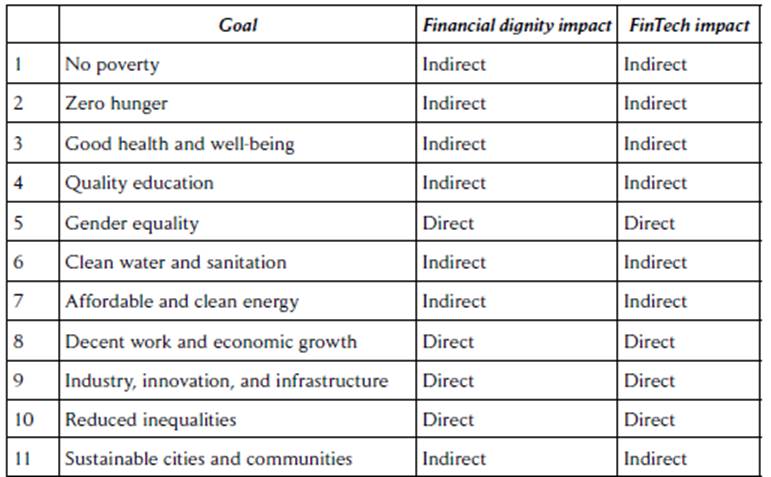

It can be concluded that FinTech can be an enabler for financial dignity from a direct or immediate effect point of view and an indirect or long-term perspective, which include several aspects of the financial environment and a broader sustainability framework (Table 4).

Conclusions

It has been identified that there are different starting points in the three cases reviewed. The financial inclusion definition already identified the openness level, which was upgraded to financial well-being in the Mexican case. It is reflected in the metrics used by the Mexican authorities, which seem coherent with their financial inclusion policy. Consequently, the performance indicators seem to capture different levels of necessities and even include or recognize the need to measure changes in the financial infrastructures.

It has been identified that the public financial inclusion statistics displayed in Uganda and Bangladesh do not match their financial inclusion proposed objectives, and it seems some others are not measured. This could be because the statistics may be in other types of reports or repositories -fragmented data sources, not a single dashboard- or those objectives do not have an assigned metric. These two jurisdictions mainly use supply information as their data feed, whereas the Mexican case includes demand data sources. This has allowed them to include medium- / long-term indicators (such as whether the individual can plan or react to emergencies or makes plans for the future).

None of the cases include real long-term indirect impact metrics that would allow assessing why the individuals have requested the service and how the services have been used -what the real impact has been. This may be because long-term indirect effects are more difficult to measure and identify -the shorter the effect, the more accurate and easier to delimit. The three countries consider FinTech a key element in supporting financial inclusion; however, it is still an early stage for the metrics designed. An adequate balanced framework that impulses technology as an enabler in a sustainable way may need to be set up to secure the financial integrity of the markets.