But tonight's the night or didn't you know that Ivan meets G.I. Joe

(…)

Now it was G.I. Joe's turn to blow

(…)

What does it take to make a Ruskie break? The Clash ("Ivan Meets G.I. Joe"-Sandinista!, 1980)

Introduction

Wars, in general, are phenomena closely linked to economic crises. To cite a few examples in support of this claim, it is worth mentioning the Great Depression (1929) in the interwar period, the Vietnam War (1955-75), and the problems in us public finance or the impacts that the Korean War (1950-53) and Yom Kippur War (1973) had on prices of top commodities in international trade. The direct and ripple effects of the Ukraine conflict on the contemporary international economic order are also a case in point. Nevertheless, this current conflict reflects a qualitative difference from the aforementioned examples; as Gilpin has stated, as if also describing the contemporary scenario, this war seems to be "not merely a contest between rival states but political watersheds that mark transitions from one historical epoch to the next" (1988, p. 605).

Last year, as the global economy was bearing the brunt of the coviD-19 pandemic and the Chinese economy going through uncertainty, the Russia-Ukraine war worsened the situation by severely impacting the world economic order. The global economy suffered financial market volatility, inflation, the reduction of tax incentives, and the crisis of multilateralism (IMF, 2022a; Bis, 2022). As a matter of fact, before the beginning of Russian operations in Ukrainian territory, the world economy was still recovering from the economic costs of the COVID-19 pandemic with risks of recession still high.

The current Russia-Ukraine conflict has complex origins and dynamics, in terms of both the historical relations between Russia and Ukraine and Western interests-especially those of the United States via the expansion of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)-in the region along with emphasis on the processes of neoliberalization in the region after the end of the Cold War. The Ukraine crisis can be viewed as a consequence of geoeconomic and geo-strategic dynamics that have interpenetrated and intensified especially since the Euromaidan demonstrations in 2013 (van der Pijl, 2018; Yurchenko, 2018). The current conflict in Ukraine with its origins going back to 2014, can be interpreted as "a multiplier of ruptures in an already fragmented world" (Wolf, 2022, p. 4) or, in other words, as yet another fundamental causal mechanism-that goes back to the 2007-2008 financial crisis and the coviD-19 pandemic-in the broader process of transforming the International Rules-Based Liberal Order (LRBLO) (Mendonça et al., 2022; Merino, 2021; Ramos et al., 2022).

The economic sanctions imposed by the United States, the EU, and Western powers on the Russian Federation, especially those implemented after February 22, 2022, can be considered a crucial aspect of such a causal mechanism. For some experts, the current economic sanctions, together with the "de-globalizing" movement, are indicators of the softening of IRBLO (Brancaccio & Califano, 2023). As per the official statements, the objectives justifying the sanctions against Russia are weakening its economy and undermining political support for President Putin within the Russian population.

Furthermore, President Joe Biden in some of his speeches, with a strong Cold War rhetoric, has emphasized that the sanctions, in fact, have the objective of unifying the West or the "free world" as he called it. However, the Europeans are speculating that these sanctions will bring great economic costs. How to interpret the systemic effects of the political decisions of the most relevant state actors on the international stage? In other words, how can the consequences of Western economic sanctions against Russia be explained as an exertion of us financial and military power? Why does this conflict mark a transition from one historical era to another? How will the ruse of nature manifest itself in the objective process of history?

Antonio Gramsci, inspired by Vico, Hegel,1 and Marx, suggests an understanding of the movement of history as one that is fundamentally a "ruse" Despite the protagonists of history deliberately aiming toward a purpose, their praxis very often brings about the opposite result. Time and again, active social actors also come to "obey" the imperatives of history, as if subordinated to Vico's natura (nature); Gramsci had observed these inevitabilities as the "ruse of nature at play."2

Global power shifts are imminent but not necessarily immediate. In fact, contemporary world politics look more like a "systemic chaos" (Arrighi et al., 1999), a phase of exhaustion of neoliberal globalization and its power projection. The world order is retained through the military-strategic and geopolitical equilibrium, and any change in the order brings fundamental shifts in societies. Every hegemonic power relation involves complexities and has its foundations in the world beyond the state apparatus. Changes and disruptions in the world order create huge impacts on hegemonic power relations, as well. Hence, the hypothesis here is that the Western sanctions imposed on Russia, whose objective is to "unify the Western world against Russian aggression," as Joe Biden put it, proposing a (re)newed era of us leadership, are catalyzing divisive forces in the fashion of "ruses of nature" Thus, the "ruses of nature" appear to be in action through dialectical opposition in the struggle for hegemony in contemporary times through the creation of a Cold War scenario via an aggressive media narrative aimed at disciplining and peripheralizing some capitalist countries, particularly European allies. The us sanctions have backfired and brought about an acceleration of the global power shift toward the Eurasian axis as well as a new globalization with China in a significant role (Jabbour et al., 2021).

Some aspects of the current situation: The ruses of nature

The current situation of conflict between Russia and Ukraine after the military operation of the Russian forces in Ukraine provoked a knee-jerk reaction of the West and NATO, led by the United States of America. A visible form of this reaction was the impostion of economic sanctions intended to weaken the government of Vladimir Putin, its political legitimacy, and the economic foundations of Russia. These series of events have forced us to reflect on the past, present, and future of the international economic order and global governance.

In this context, the issue of both us-intended and unintended consequences of the sanctions come to the surface, as well as the literature of unintended consequences (LUC) or effects. The expression "unintended consequences" was coined by the sociological functionalist scholar Robert Merton (1936). The expression has gained various theoretical interpretations in the fields of international relations and international political economy, many of them departing from the original functionalist frame.3

From a classical perspective, Jervis (1997), for example, pointed out that social actions give rise to unintended consequences. Realists of classical and structural inspiration have also talked about the tragic nature of politics, and unintended or unanticipated consequences are the underlying reality of international politics (Lebow, 2003; Mearsheimer, 2001). In a different vein, historical institutionalists and constructivists have developed this idea to criticize and expose the limits of the rationalist perspective on international institutions and their design (Fioretos, 2011; Onuf, 2002).

Despite the relevance and insights of LUC, it reproduces some blind spots about the realm of international politics. First, LUC does not present a critical view (in the Marxian sense of "critical") of unintended consequences of events but only recognizes their presence in international politics and, in some cases, provides a phenomenal (or epiphenomenal) recognition of their social existence. Second, LUC pays more attention to specific cases and not enough to the bigger picture. Third, even while maintaining totality as its key concept, LUC reproduces the dichotomy between IR and IPE and does not recognize or present the international political economy as the ontological starting point of a conjunctural analysis of the subject. To rectify these blind spots and allow a critical interpretation, we will present a Gramscian-inspired analysis of the LUC (Cox, 1994, 2002; Morton, 2007).

To conceive the future based on the concrete possibilities of the present, the historicity of dynamic social processes must be considered as a critical and reflective aspect of the process. Therefore, while investigating any huge-impact event, the concepts involved must not be hypothetical or objects of contemplation but be fact-based. The deliberation process needs to be an unfolding of a dynamic and historical totality as a concatenation of social events that puts the event into the right perspective; in sum, a concrete totality and comprehensive reality can be unveiled by rich and complex dialectical processes (Kosik, 1976). In our analysis, the real historical process is not the result of beliefs and opinions reasoned with critical consciousness that converts nature into history as it comes to know it; the process is to reach the shifting objective reality of the world that shapes history in its becoming.

Gramsci (2014, Q6§168, Q1§135) often presented the prevailing historical movement as "ruses." The reason for this belief is that Gramsci, similar to Vico, arrived at the limitations of common-sense praxis, which allows actors to establish connections between different issues without knowing what principles they depart from and form conceptions of a limited view of a whole or a false totality. In the famous paragraph in the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Marx stated, "Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past" (1999, p. 5). Thus, social actors, in their active roles, also come to "obey" the imperatives of history, namely, the "ruse of nature"

Before focusing on sanctions and their specific effects, let us reflect on what kind of ruse of nature appears today as a concrete possibility, operating within real historical processes in close relation with the current crisis of the IRBLO and the struggles over hegemony related to it. It is well known that us hegemony4 has crucial financial and monetary tools based on the monopolistic use of the us dollar for global trade, international reserves, international financial transactions, and so on. Though these transactions are operated through complex mechanisms that lack transparency, two of them are essential for all stakeholders. The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) network for international interbank transactions and the Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS) are the main international clearing houses used for high value transactions in dollars. Both these mechanisms are crucial tools for us hegemony to operate in the global economy.

The abovementioned transaction methods grant the United States the right to issue the dollar, which the former President and Finance Minister of France, Giscard d'Estaing, rightly described as an "exorbitant privilege" (Eichengreen, 2011). The United States, for example, would not face a crisis of balance of payments because its imports are bought in its own currency. Furthermore, an excessive expansion of its monetary base would not be mechanically reflected in an internal inflation because this expansion is shared with the entire world. An important political counter-face of this exorbitant power of the United States over financial institutions is observed when at the time of application of economic sanctions, some actors challenge its global hegemony or its leading position in the IRBLO.

Since the 2007-2008 financial crisis, engendered by the ill effects of neoliberal globalization or capitalism hegemonized by finance, many recall the famous Gramscian description of such situation as a "twilight" (Gramsci, 2017, Q3§34), where "the old is dying but the new cannot be born" (Menezes & Ramos, 2018). This means that the hegemonic international order persists without the objective possibility of materially overcoming it through new mechanisms of transactions and other national currencies. This overcoming also includes the minilateral institutions (G7, NATO), which sometimes act as unilateral mechanisms or appendixes of us power and interests. These groups and organizations are the geopolitical arm of neoliberal globalization, which ironically have presented themselves since the 1990s as instruments for overcoming the prevailing geopolitics, the supposed end of a historical era. However, such an end of an era reached a cul-de-sac, and contradictions have emerged from neoliberal globalization. Thus, it does not come as a surprise that the CEO of BlackRock, Larry Fink, who heads an institution that manages over 10 trillion dollars, stated in an open letter to his shareholders that globalization as we know it (i.e., neoliberal globalization) is coming to an end (Fink, 2022).

However, until now, none of the incipient alternatives has been deployed to be enforced in their real transformative power, and certainly will not be as fast as the response that the current sanctions demand from the actors involved. The development of these alternative forces, now as a concrete possibility, presents serious implications in the context of maintaining the current us hegemony.

To analyze the matrix involving the war, the sanctions, and their relationship with the IRBLO crisis, along with the underlying aspect of us hegemony, we propose to start with a famous Gramscian note. Gramsci returned to Marx's A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (2013) when he stated that "a society does not set itself tasks for whose solution the necessary conditions have not already been incubated" (Gramsci, 2000, p. 106). From this concrete perception of a possibility of developing alternative forces, we observe that, whenever such ruses of nature are in play, we are faced with events that are immediately perceived as accidental or circumstantial in significance. Thus, these events are inadvertently dealt with, by the acting leaders, as if conjunctural, although in reality they are organic to the unitary historical process of which the world consists, being closely related, therefore, to concrete hegemonic dynamics.5

A restructuring of the world order appears to be inevitable, although it may not happen immediately. Presently, global politics appear to be in a state of flux. After more than a year of war, the Western sanctions against Russia, the objective of which was to "unify the Western countries" and renew the IRBLO and us hegemony, are increasingly catalyzing a trend in the opposite direction. By creating a Cold War environment, aimed at disciplining some capitalist countries, a real "ruse of nature" has been provoked. The disuniting forces are expressed through the fracture of the historical bloc organized around us hegemonic leadership, as well as through the shift of power toward the Eurasian axis, including an embryonic but robust new globalization with China in a significant role.

The political economy of the current economic sanctions

On February 21, 2022, Russia recognized Donetsk and Luhansk as independent regions and ordered troops to protect the region as a whole. Starting on February 22, 2022, in an unprecedented movement in the history of the international economic order, the countries of the G7 and the European Union, led by the United States, imposed a series of financial sanctions against Russia as a response to the country's military operations in Ukraine (Morgan et al., 2023).6 In the first phase of the implementation of the sanctions, the SWIFT interbank system blocked certain Russian banks, in addition to about half of the reserves of the Central Bank of Russia, worth us$630 billion in international currencies and gold.

Sanctions against Russia had been established since the annexation of Crimea in 2014; the Central Bank of Russia reduced its reserves in dollars thereafter. However, over 50% of Russian international reserves are in dollars, euros, or pound sterling and are in France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and Australia. Further, the United States has also imposed sanctions on Russia's sovereign fund (Russian Direct Investment Fund [RDIF]) and on specific Russian individuals and entities (Congressional Research Service, 2022; U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2022).

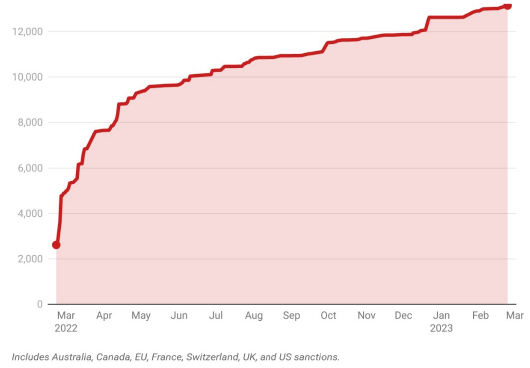

Following the literature, sanctions can be defined as "restrictive policy measures that one or more countries take to limit their relations with a target country in order to persuade that country to change its policies or to address potential violations of international norms and conventions" (Morgan et al., 2023, p. 3).7 Regarding the role of such sanctions in the case of Russia, first, since 2014, over 13,000 sanctions were imposed on Russia, and among them, approximately, 11,500 were imposed after February 22, 2022 (Cameron, 2014; Castellum.ai, 2023, Graphic 1; "EU extends...", 2017). See Figure 1 for a visualization of the sanctions that year. In 2014, 2022, and 2023, the consequences of these sanctions on the Russian economy did not directly impact the approval ratings of the Putin administration; during 2014 and in the past two years (March 2022 and February 2023), Putin's approval ratings remained in the range of 80%-85% (Crimmino, 2018; Statista, 2023). Therefore, despite the clear consequences of the sanctions for the Russian economy-the economy's contraction and inflation, in particular8-these issues were already foreseen to some extent by the Russian government when it decided to start operations on Ukrainian territory: "Russians, unlike the Western world, learned from the sanctions following the annexation of Crimea" (van Bergeijk, 2022, p. 12). All the above statements point to the limitations of imposing sanctions.

Second, sanctions' effectiveness is a prominent topic in the specialized literature about sanctions (Baldwin, 2000; Drezner, 2000, 2003; Morgan et al., 2023; Teichmann & Wittmann, 2022; van Bergeijk, 2021, 2022). Hence, a fundamental aspect of upholding the success of sanctions concerns the need to differentiate between their effects and their effectiveness (Harris, 2020; Hausmann, apud "The Big Question", 2022; Mulder, 2022a, 2022b; Nephew, 2018). In this case, as already noted, the effects of the sanctions are evident for the Russian economy; what remains unclear is their effectiveness. When a country is a part of the sanctioner's cooperative body, it may have different reasons to pursue sanctions. In sum, "whether or not a sanction is considered effective ultimately depends on the sanctioner's foreign policy objective" (Teichmann & Wittmann, 2022, p. 5). Having in mind the us public discourse, that is, the hegemonic state leading the western historical bloc and its economic sanction policies, the following question arises: will the sanctions lead to any substantive change in the Russian regime and/or they will they have repercussions that could bring a significant decrease in the ability of the Putin administration to wield power in the conflict region and soon discontinue its operations?

A key aspect to determine the efficacy of a sanction is the possibility of sanction circumvention or adaptation by the sanctioned. If, on one hand, the current sanctions are more extensive than they were in 2014, on the other hand, the United States is trying to fix the IRBLO and maintain its global hegemony by hitting the Russian economy, which is much better prepared and more resilient (van Bergeijk, 2022). Hence, the answer to both the questions posed in the previous paragraph has been negative, given the counter-sanctions and other measures of circumvention and adaptation taken by Russia and their consequences. Russia seems to be very successful getting around crucial sanctions, which were implemented to degrade the Russian Army. Regarding access to advanced chips and integrated circuits made in the EU and other allied nations, for example, strong evidence exists that Russia has been able to get them through developing countries, such as Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and Kazakhstan (Nardelli, 2023; Teichmann & Wittmann, 2022).9

A central aspect in this regard is that in the numerous sanctions imposed by the United States and its allies since the World War II, as a rule, the countries that were subject to the sanctions were small or medium-sized economies, without significant economic connections with the United States and/or its allies of the "geopolitical West." That is, the application of sanctions, in general, did not generate great costs for the United States and its allies (Mulder, 2022b). Russia's case is quite different, which leads us to think both about the systemic spillover effects of sanctions (and potential effects of counter-sanctions and other Russian measures) and about their consequences for us allies, in particular, with an emphasis on Europe. In fact, as van Bergeijk (2022) identifies, since 2014, the sanctions against Russia have illustrated the comparative vulnerability of European countries and their weakness in organizing comprehensive, collective, and effective sanctions. In other words, it appears that sanctions against robust economies or big powers are not feasible without compensatory policies for the sanctioning countries and for the rest of the world (Mulder, 2022b). According to the literature about sanctions, positive aspects of sanctions bring promise and reward while the negative sides result in threat and punishment. Only a fine balance of these two aspects has chances of success (Caruso, 2021; van Bergeijk, 2022). Nevertheless, such policy does not seem to be on the horizon of the Unites States, whose focus has so far been only sanctions per se, and not on compensation mechanisms for the world economy in broader terms.

Eric Cantor, a key figure in the sanctions policy against Iran, has also been pessimistic about the effectiveness of sanctions. He claims that Western countries probably will not maintain their unanimity about sanctions. Moreover, for them to be effective, secondary sanctions10 would be necessary; this is a topic discussed by both us senators and senior officials of President Biden (Stein & Whalen, 2022; Zengerle, 2022). However, such action would be harmful to the already undermined IRBLO and the material forces, institutions, and ideologies that sustain us hegemony (Cox, 1994; Morton, 2007). If successive sanctions come into effect, it would put us hegemony and the western historical bloc in a collision course against China, India, Saudi Arabia, "and almost 60 states that refused to back a UN resolution denouncing Russia's invasion" (Evans-Pritchard, 2022, p. 3).

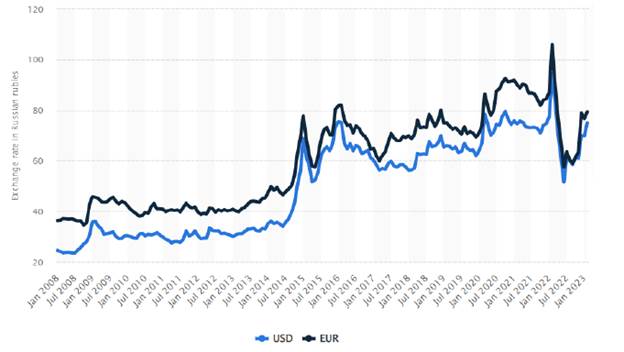

Third, it is necessary to highlight the impact of these sanctions on fuels. A short-term consequence of the economic sanctions on Russia was the devaluation of the ruble. Without sufficient reserves available, the Central Bank of Russia has lost part of its capacity to contain the devaluation of its currency. In a few days, it lost about 30% of its value in dollars-the fallout of an action that has not only impacted the Russian economy but also the Russian population in broader terms through loss of purchasing capacity. However, after March 7, 2022, the ruble appreciated again, probably influenced by the payment of us$117 million in interest by the Russian government against its debt bonds and their increased production and export of oil to its main foreign markets.

This proves that although the European Union (EU) could accelerate its processes of replacing alternative and renewable energy sources in the long term at a high cost, its present dependence on Russian oil and gas is very clear. In 2021, Russian gas accounted for about 45% of the total EU gas imports. Also, prior to the war, Russia was one of the suppliers of crude oil to the EU. Since then, the EU is trying to reduce such dependence by increasing its imports of oil and liquefied natural gas from Azerbaijan and Norway (Kardás, 2023). However, in the short and medium terms, the EU'S dependence on the Middle East for other energy sources could result in a disorder in the processes of world energy distribution, with profound impacts on the world economy in the near future and in global geopolitics (Dolan, 2022).

The efforts to strengthen the ruble in relation to the dollar were consolidated after Vladimir Putin's announcement that he would only accept rubles from the "hostile countries" as a means of payment for the purchase of gas ("Putin wants...", 2022; Vior, 2022). Regarding circumvention strategies, this step has several short-term implications for (i) Russian banks that are not prohibited in SWIFT and (ii) the types of formal or informal banks in third-party countries, which could act as intermediaries. India and China seem to be better positioned to fulfill this role. On the whole, it is obvious that despite volatilities of the exchange rate, it is possible to anticipate a new rise and stabilization of the Russian ruble at the same level since 2014 after the first wave of Western sanctions (Figure 2).

Source: Statista (2023).

Figure 2 US dollar and euro exchange rate to ruble from Jan 2008 to Feb 2023

Since the beginning of the sanctions in 2014, oil has been a fundamental resource for Putin's policies for international projection. In 2015, the rise in oil prices was instrumental in financing Russian operations in Crimea; today, Europe's dependence on Russian oil (and gas) is a key point in understanding the very limits of sanctions (and their intensification) and the efficacy of counter-sanctions. In a post-pandemic context, bearing the economic and political costs of blocking Russian oil (and gas) is not an easy choice for European countries. That is, the policy of what we might call the "petroruble"-the Russian policy of pegging the ruble to oil through sales of Russian oil in rubles-is central to the stability of the Russian currency and to the intensification of actions already underway, specifically that of Russian approximation and partnership with actors like China and others in the Asian region (Morgan et al., 2023).

These partnership activities have been ongoing since 2015, in response to Moscow's growing sanction-induced difficulty in gaining access to Western markets. Since then, Russia has been forging closer ties with China and Central Asian countries, as well as celebrating a series of agreements with Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, as well as deepening ties with India.

Circumvention strategies and the us financial hegemony: SWIFT, CHIPS, and beyond

How is the power of world finance, based on the hegemony of the dollar, affected by such processes? One of the fundamental aspects of us hegemony is its dollar monopoly (seigniorage) and its financial power.

The key pillars for this are the SWIFT system, CHIPS, and the power of the dollar. The dollar is the main currency for economic transactions throughout the world. About 60% of international reserves are in dollars, the international financial system revolves around the us economy, and the main mechanisms for organizing and managing such transactions are largely controlled by the United States. Despite having Brussels as its headquarters, SWIFT has a data center in Virginia and allows the United States to monitor its financial flows across borders, with emphasis on transactions in New York, where about 95% of payments are made in dollars. The CHIPS makes it possible to clear large interbank transactions. Currently, they process about US$1.8 trillion daily and are subjected to us laws and Federal Reserve regulations (Mukherjee, 2022).

The use of financial resources by the United States is predictable in a critical situation like the current one, especially while facing a great power like Russia, as a strategy to maintain its hegemonic power. However, unanticipated consequences can emerge precisely from the use and the abuse of these power resources, resulting in complex configurations and dynamics that are totally different from those previously intended, with serious consequences to us hegemony, the western historical bloc, and the IRBLO.

SWIFT has been frequently used for sanctions by the United States and the EU, and with this in mind, Russia, since 2014, has already been working on reducing its dependence on the dollar in payment systems. In January 2022, Dmitry Medvedev, Vice President of the Russian Security Council, opined that Russia getting disconnected from SWIFT seemed improbable to him. However, he noted that the alternative Russian System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS, for its acronym in Russian) could serve as an equivalent to SWIFT, in case Russia was disconnected from SWIFT (indicating that this scenario was considered a real possibility by Russian leaders) ("Medvedev convinced...", 2022).

Since 2014, Western analysts have warned about the possible consequences of such use of SWIFT by the United States. In 2014, The Economist published an article that expressed this concern, saying "it could lead to the creation of a rival. (...) If China and other countries that feared being subjected to future Western sanctions joined the Russian venture, it might become an alternative to SWIFT" ("The pros and cons of a SWIFT response", 2014). In February 2022, other analysts have warned that expelling or suspending Russia from SWIFT could be counterproductive, as it would generate an acceleration of the rapprochement between Russia and China. China, in an attempt to break away from us financial hegemony, including CHIPS, has also developed its own interbank payment system, Cross Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), which is currently in a state of expansion. According to the Chinese state newspaper Jiefang Daily, in 2021, a 75% increase in financial operations was recorded compared to about 80 trillion yuan (us$1 trillion) in transactions involving financial institutions from 103 countries in 2020 (Albano, 2022). Currently, 40% of international payments are made in dollars-the rate of the yuan is 3%. Daily transactions through CIPS are around us$50 billion, whereas transactions via SWIFT are approximately us$400 billion (Goldman, 2022). Although in the short term the CIPS does not represent a replacement for the Western system, in the medium term, and in combination with the digital yuan, CIPS can become a real alternative payment system for Russian bank operations.

In the present situation, the tendency of Russia and China toward approximation and economic interdependence is predictable and a concrete reality. This ally, in recent years, is accelerating cooperation processes like the intensification of commercial relations and investments. Since 2014, with the annexation of Crimea, bilateral trade has expanded more than 50%, with China becoming the most important destination for Russian exports. The multibillionaire swap agreement between the central banks of the countries is another similar move. In 2014, 3.1% of trading currency between Russia and China were in yuan, and in 2021, it reached an amount of 17.5% (Albano, 2022; "China-Russia trade...", 2022; "Sanctions on Russia...", 2022).

The imposed sanctions and the adhesion of the financial institutions of Russia to the international payment system of China will contribute to the strengthening of the CIPS and will not only further unite the two powers but also put at risk the future of the us dollar as a currency reserve of these countries in the short term, further involving other actors in the medium and long terms. The unprecedented sanctions imposed against Russia could cause other countries to rethink keeping international reserves only in dollars, particularly those countries that have some possibility of conflict with the United States or EU countries (Eichengreen, 2022).

At this point, it is important to identify some important developments that have taken place since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine conflict: 11

Saudi Arabia has carried out negotiations with China so that part of its oil sales will be in yuan and no longer in dollars. In fact, a striking contrast was noticed between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping's visits to Saudi Arabia in 2022. While Biden's visit produced a few tangible gains (as per analysts from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), Xi's visit facilitated China and Saudi Arabia's agreements in signing more than 30 energy investment deals toward developing the comprehensive strategic partnership between the two countries.

India, the world's number three importer of oil and Russia's top outlet for seaborne crude nowadays, has paid for Russian oil in non-dollar currencies, including ruble and UAE dirham. Further, talks are underway for a direct yuan-ruble exchange system for China to pay for Russian oil imports. The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and China have negotiated the establishment of a monetary system independent of the current model of the international economic order.

In early 2022, Iran proposed the creation of a new currency aimed at commercial transactions between member countries of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). China has been developing, together with Chile, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Singapore, a reserve fund in yuan, named Renminbi Liquidity Arrangement, of around us$2.2 billion, which will be administered through the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

The volume of resources mobilized by the international oil trade is around us$14-15 trillion annually, and the effectiveness, continuity, and unfolding of the abovementioned actions linked to the "petroruble" can have significant impacts for the dollar. After the reclaiming of us financial hegemony at the end of the Bretton Woods System, the guarantee of the sale of oil in us dollars was fundamental for the maintenance of the so-called "exorbitant privilege" (Engdahl, 2004). Today, we are observing the first major challenge to the us dollar hegemony, with consequences for sales possibilities, for example, in rupee, yuan, lira. Further, in the case of the yuan, there is a possibility of spillovers to oil trade relations with Middle Eastern countries and corresponding developments for the Belt and Road Initiative.

Although major structural changes in the global political economy may not occur in the short or middle terms, uncertainties in the current world order must be observed to understand its possible outcomes. These large-impact unfolding of events are also appropriate for understanding the working of the ruses of nature, as well as their impacts to the power equations at the global level. For Arslanap et al. (2022), the main intended outcome against the imposition of sanctions should be the decrease in demand for international reserves, which is associated with market and technology innovations related to the electronic currency market (BIS, 2022).

The fall of the dollar as an international reserve currency, from 71% of reserves in 1999 to 59% in 2021, as well as possible tendencies in the international monetary system in the current century, can both be better explained and understood if the current situation is observed closely. In other words, the present world situation has directly impacted the world capital market. In 2021, the international reserves of central banks totaled us$12.83 trillion, and these reserves were mostly in us and European bonds, with 60% in dollars and 20% in euros (Dolan, 2022).

Concluding remarks or (re)presenting the conundrum

The war in Ukraine and the consequent financial sanctions against Russia are an analytical challenge that raises theoretical reflections and demands critical examination of the ongoing historical process.

In reference to Hegel's Logic, Marx emphasizes that "at a certain point merely quantitative differences pass over by a dialectical inversion into qualitative distinctions" (Marx, 2004, p. 423). As discussed, the changes and dynamics associated with the current juncture do not necessarily point toward transformations or ruptures in the short term but rather have accelerated a process of qualitative and spontaneous changes, which are open to global political and economic reorganization. The us hegemony, particularly in the financial realm, will not disappear soon as a direct result of the present movements or others. Nevertheless, the ongoing war in Ukraine shows that the minute changes in the medium to long term, once closely related to the structural reality, can bring qualitative and complex transformations. As Gilpin (1988) has pointed out, these changes mark the transitions from one historical epoch to the next. To a large extent, such changes can lead to very different transformations or even become opposite to a logical progression from actors' initial intentions and the forces involved in such processes.

The war in Ukraine with its developments, surrounding theories, and, particularly, the economic sanctions imposed by the United States and Western allies appear to be a unique moment in history in the context of deeper structural changes in the international order. China and the Russian Federation are the main proponents of these geoeconomic transformations. Hence, despite the clear intentions of the United States and its allies to economically isolate Russia to maintain the international order under us leadership, the consequences of their actions are currently leading to unexpected results.

If, on the one hand, the consequences of Western sanctions against the Russian economy cannot be underestimated, on the other hand, it is well known that sanctions are often a double-edged sword, with destructive effects for all the actors involved.

Actions that seek to restore order can, through complex changes and syntheses, present themselves as a ruse of nature that makes unwilling leaders come to obey the "imperatives of history" (Gramsci, 2014, Q1§135; Q15§11). In this process, contradictions have manifested in multiple scales; since the beginning of the conflict, a lot of anti-war protests have been organized in European cities, some of which were by the radical left and some others by the populist right, with many of them openly showing anti-NATO characteristics. In Germany, particularly, at the end of 2022, some claimed that "Germany is serving as a puppet exclusively for American interests and those of NATO" (Jones & Minder, 2022, p. 1).

The measures adopted to restore the IRBLO and the us hegemony are accelerating processes of structural and civilizational changes. In this regard, Caixin and Nikkei pointed out that Chinese steel mills are increasingly using the yuan to buy iron ore; furthermore, the IMF and the Financial Times have warned that sanctions against Russia could erode the us dollar's hegemonic power. Moreover, in Germany, in accordance with a report from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, it has been suggested that the decoupling of the EU from China would reduce Germany's gross domestic product by 1% in the long term. In this context, the chemical industry giant BASF has stated that it will most likely cut 2,600 jobs as Europe's largest economy braces for the economic recession closely related to the energy crisis that intensified after the beginning of the conflict (Jolly, 2023; Li, 2023).

The Global South is also an interesting example in this current crisis. G20 countries, mainly Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico and South Africa, are once again ignoring the pressure from the United States and the geopolitical West to isolate Russia. Furthermore, the next two G20 summits, which will be held in Brazil (2024) and South Africa (2025), could be good indicators of the significant position of the Global South in the struggle for hegemony at the world level.

As expressed by Vior (2022), "Before our eyes, we are witnessing the collapse of Europe, the reorientation of Russia towards Eurasia, the self-closuring of the United States in its area of dominance and China occupying all the spaces that its competitors are leaving vacant" Afterall, in a moment of interregnum or systemic chaos, like the current one, the ruses of nature manifest as inherent contradictions in human actions. The valuable Gramscian conception regarding the relationships between structures and superstructures in the development of history allows us to understand the relationships between the measures undertaken by actors, social forces, and their concrete results. Particularly, in a context of hegemonic crisis, such dialectical processes are crucial to grasp the changes in the world order.