INTRODUCTION

Corruption is an obstacle to maximizing efficiency and effectiveness in the use of social and economic resources, and constitutes an additional risk affecting economic development and democracy. Since those most affected by corruption are the poor and the most vulnerable population sectors, there are moral reasons to fight corruption and reinforce business ethics. In fact, incentives should stress the risks of corrupt behavior and highlight the benefits of transparent and ethical practices (Boehmb and Graf, 2009).

Entrepreneurs who create new companies are aware of the role that ethics should play in their firms, and how ethical practices can influence their companies' success or failure. The behavior of individual entrepreneurs both inside and outside of their companies is governed by ethical standards that allow them to avoid illegal business practices (Saiz-Álvarez, 2008). Nonetheless, when asked about practices within each sector, entrepreneurs indicate that they perceive unethical behaviors that they deplore but to which they must adapt (Vaca et al., 2010). According to the Colombia's National Directorate of Taxes and Customs - DIAN, only 40 % of companies are currently making tax payments, constituting over six billion pesos of tax fraud annually, as businesses artificially increase their costs by inflating payments.

In the last ten years, 64 % of the nearly half million cases of corruption in developing countries have been related to foreign investment by multinationals (Aldaz et al., 2012). According to Transparency International (2014), Colombia ranks 94th in terms of corruption among 176 countries, with a score of 36 out of 100, where zero represents the greatest perception of corruption and 100 its complete absence). In fact, 93 % of business owners perceive that companies in Colombia offer bribes, 61 % state that bribes are required to obtain needed things, and that three out of every one hundred companies expect to pay bribes to do business (Gutiérrez, 2013). Bribery accelerates business and administrative processes (as reported by 49 % of respondents), and 36 % say that it is sometimes the only way to obtain a service. This sad situation continues over time, as 40 % of Colombians are afraid to report it, 46 % believe that complaining does not make any difference, and 7 % do not know how to report acts of corruption or tax fraud. As a result, 32 % of participants in the study believe that the Colombian government is completely controlled by private companies acting in their own self-interest, and 27 % believe that the government is largely controlled by those companies (Transparency International, 2014).

Corruption weakens the already weak democratic system. According to Transparency International (2009), corruption in Colombia has become a structural feature of the economy. Nonetheless, their data is not entirely reliable, given the illegality and opacity of the process. Corrupt agreements are usually secret and not at all transparent, so opportunities to participate in them are limited. Moreover, high barriers to entry and investment can generate unrecoverable costs without any possible alternative destination. Corrupt agreements have significant complications that represent transaction costs for corrupt actors (Boehmb and Graf, 2009). For these reasons, the real cost of corruption tends to be unknowable in the absence of reliable data (González-Espinosa and Boehm, 2013).

Boehmb and Graf (2009) recognize various practices as examples of corruption, including bribery, extortion, embezzlement, favoritism, nepotism, fraud, and collusion among firms to surreptitiously allocate market share or set prices. These illegal practices have their own logic and their own economic mechanisms andrealities. Interactions between corrupting and corrupted are hidden in a "black box", and the majority of formal economic models do not consider transaction costs deriving from corrupt practices, the institutions involved in those practices, or their complexity. Instead, corruption is usually minimized as a distribution problem. In addition, there are differences regarding the level of corrupt acts and their value. We distinguish low-level corruption carried out by police officers, for example, from high-level corruption, usually attributed to politicians and leading business figures.

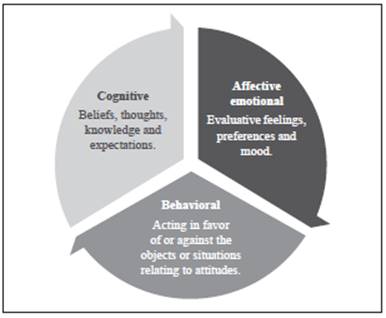

The subjective interpretation of facts -not facts themselves- determine emotional responses. People's cognition, i. e. the way they perceive and conceptually structure the world, leads to their own emotions and behaviors (Ramos et al., 2009). Corrupt behavior is a quality that cannot be directly observed or measured in a population of entrepreneurs. Instead we evaluate the observable variables of cognition, emotion, formal education, and behavior.

According to Bolivar (1995), the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions are in constant interaction and are cyclical, i. e. they can be understood as both antecedents and consequences of actions, since they modify the dimension, and therefore people's attitude towards objects and situations.

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TAR) (Fishbein and Azjen, 1975; Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977; Fishbein, 1980) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TCP) (Ajzen 1988, 1991; Ajzen and Madden, 1986) are used in the study of behaviors, but these models are insufficiently predictive (Caballero et al., 2003). This paper seeks to indirectly identify Colombian entrepreneurs' attitudes towards corrupt businesses from a threefold standpoint incorporating the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions, and aims to analyze corrupt behaviors and related emotional and cognitive factors among Colombians in business, based on their level of education, their sex, and their level of experience with their companies: whether they are nascent entrepreneurs, relatively new entrepreneurs, or well-established business actors.

This paper presents theories that describe the characteristics of entrepreneurs who create new businesses, an approach to individual ethics and the ethical practices of their businesses, corruption, the most common crimes in Colombia, a brief diagnosis provided by the Colombian National Directorate of Taxes and Customs -dian), and ethics in higher education.

ESTABLISHING BUSINESSES

The establishment of a new business entails various forms of action to achieve desired results. This paper analyzes entrepreneurship as the creation of a business by engaging in rational behavior to optimize the use of available technologies and financial resources (Fontela, 2006). These activities are not standardized: They emerge from the entrepreneurial imagination, the perception of new opportunities, and innovation (Dávila, 1996).

To Neoclassical economists, business firms are legal entities whose primary function is production with maximized benefits. They are immersed in an environment full of constraints. Marshall (1890) sees modern economic conditions as improved, despite their complexity; because they create more business opportunities. Hayek (1991) holds that entrepreneurs are important in highly developed economies because they constantly search for unexploited opportunities to achieve an advantage over others, and Kirzner (1986) describes the human propensity to discover useful knowledge and its limits, with the knowledge of market imperfections and how they can be used for self-benefit.

According to McClelland (1970), entrepreneurial behavior is contingent on the personal motivations that the environment provides. The motives of entrepreneurs are not always economic, although those who succeed are more sensitive to economic stimuli. Moriano (2005) says that entrepreneurs are optimistic and risk-taking, optimistic, and persistent long-term planners with a high capacity for work.

According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM, 2011), entrepreneurship expressed as the establishment of businesses includes potential actors in this field, i. e. individuals who have the skills, knowledge, and desire to start a business, even though the idea has not yet been put into practice. The behavior of companies, their ethical performance, seems to differ in accordance with three characteristics:

Companies established by nascent entrepreneurs, defined as enterprises launched up to three months earlier by a person who is either self-employed in that company or in combination with other employment;

New entrepreneurs with companies that have been in operation for a period of 3- 42 months, i. e., paying salaries or wages to a person in addition to him or herself, either self-employed or in combination with other work;

Established entrepreneurs with companies that have been in operation for more than 42 months, paying wages or salaries to a person in addition to him or herself, either as self-employed or in combination with other work.

APPROACH TO ETHICS

The term "ethics" comes from the Greek word êthos which means "character or way of being". Having good character is crucial in the life of an individual and others around him or her, because external factors may condition his or her decisions, but character will define them. People get accustomed to making choices, and ethics makes them conscious of the ultimate goals that they pursue (Cortina, 1994). Nevertheless, modern life is increasingly hurried and many organizations, including private companies, dictate to individuals what they should do and how they should act. These individuals, however, can achieve increasing independence and greater freedom while building new and more controllable spaces (Serrano, 2006).

When applied to specific areas of action such as business, family, politics, and ecology, among others, this capacity may go beyond the realm of theory or reflection and be put into practice. Business ethics, for example, is a form of applied ethics that contributes to a business's humanization by establishing corporate values and an ethical business culture (Hamburger, 2004). Minimal Ethics refers to principles that don't contradict fundamental values such as respect, responsibility, dignity, autonomy, and trust (Cortina and Conill, 2000; Gutiérrez, 2007).

Capitalism works from the assumption that Homo economicus is found in the market context, which is to say an individual who makes rational decisions, maximizes business opportunities, and behaves selfishly. Such individuals are insatiable; they are always seeking to maximize their advantages, act on their preferences, get more for less, and live to make decisions based on opportunity costs (Alcoberro, 2007). The market can be fair, as long as it benefits both individuals and communities. This outcome depends on forms of justice that may adopt two types of trade: benevolent and malevolent trade. The former is conducted among family and friends, and generates wealth and social utility because it satisfies their own interests and those of their counterparts; and malevolent trade between strangers, guided by self-interest and the greed of employers (Murillo, 2007).

Human beings obtain value and the freedom used to obtain it, in addition to ethically assuming the rights of agents (Gutiérrez, 2007). In this sense, Revenga (2007) recognizes a new social cartography with new social strata, the redistribution of privileges, wealth, power, freedom, and restrictions, but no one takes responsibility for those within the system who lose.

ETHICS AND BUSINESS

The ethical commitment of companies and entrepreneurs is expressed throughout the organization and sees the human being as an end in itself (Rafols, 2007). Business practices and management strategies should be constituted in such a way as to contribute to the development of rationality and morality rather than inhibit them (Carrillo, 2006).

Businesses transcend self-interest and pursue long term benefits for the community. An environment of trust, which is an essential virtue for any company and entrepreneur, can be consolidated in a business. We must acknowledge that businesses have power and exercise it upon suppliers, contractors, employees, and even upon their customers. This is especially so with reference to with monopolies, oligopolies, or business groups that have reached informal price agreements (Carrillo, 2006; Savater, 1998). But businesses and their employees must avoid psychological aggression, which can cause stress, depression, elevated heart rate, sleep disorders, headaches, and loss of self-esteem (Gutiérrez, 2007).

Business ethics and moral integrity should be at the heart of every business enterprise (Martínez, 2005). New businesses may generate social risks such as the risk of growing at the expense of their stakeholders and causing them hardships by paying low salaries or wages, engaging in false advertising, distributing poor quality goods and services, avoiding or evading taxes, or producing pollution and contributing to climate change. For these reasons, it is important to consider the need for ethical responsibility in business (Jared et al., 2011). Companies, like people, have obligations to society, and should devise and propose sustainable business policies knowing that they will be accountable for them (Martínez, 2005; Cortina, 1994). Thus, employers cannot avoid responsibility for ill effects such as pollution, poverty or inequality that result from their actions. The problem of business ethics is how to combine economic efficiency with individual freedom and the market with social well-being (Martínez, 2005).

The goal of a business is not just to produce and sell goods or services. A company must determine the appropriate means of producing them and choose the values to be adopted in the process of doing so. Companies should also determine the actions to be taken so that principals or employees incorporate these values into their activities and establish the character that will permit them to consider options and make correct decisions in keeping with the business's goals (Cortina, 1994).

Ethics is not a label; it is a representation of company's identity and behavior (Alcoberro, 2007). Companies face two ethical dilemmas: first, how to achieve efficiency in a business environment that constantly proposes the use of shortcuts such as asymmetrical negotiation, oligopolistic alliances, bribery, tax evasion, the manipulation of financial information, the super-exploitation of its workforce or the suppression of workers' rights to association. The second dilemma relates to the ongoing and constant control over the workforce, whether exercised directly or indirectly (Carrillo, 2006).

In order to behave ethically, "individuals don't need to agree with anyone else, nor do others need to agree with them. Individuals will behave in keeping with their own consciences" (Savater, 1998). Part of the responsibility of entrepreneurs is to act openly and abandon secrecy in managing their businesses. Transparency is a positive attribute for entrepreneurs, business owners, and workers. Entrepreneurs and business owners cannot operate behind the backs of their employees or of society (Lozano, 1999).

ETHICAL BEHAVIOR IN BUSINESS

Faced with the reality of ethics scandals in business, Trevino and Brown (2004) question some prevailing business myths and offer explanations for their existence. According to these authors, the principal myth is that it is easy to be ethical. They recognize that ethical decision-making in business is not simple, because consequences many have many ramifications for those operating in the real world of business. Klebe and Brown (2004) find that ethical behavior in organizations is affected by individual factors including personality and manners of socialization. These factors determine the philosophical and ideological grounding of decisions, along with external forces such as economic conditions and social and political institutions. Stead, Worrel, and Gardner (1990) suggest that behaving ethically is one of the major challenges faced by organizations, as the decision to do so depends on two dimensions, the first of which is identified in their model as the ethical past of individuals and organizations. This set of factors determines the ethical behavior of organizations as manifested by the way business decisions are made. Personal characteristics, the environment, and the restrictions presented by that environment have direct impacts on the making of ethical decisions. Making ethical decisions is also based on the personal characteristics of individuals, including the education that builds the character and personality of individuals, their socialization in different roles, their age, sex, and other significant factors such as the work environment and their experiences there, where entrepreneurs live and put their values into practice. Other environments also affect ethical decision making (Stead, 1990). When an individual faces an ethical problem he or she recognizes the situation as a moral dilemma over which a judgment must be made. This judgment will respond to a set of individual characteristics that lead to an intention expressed as a corresponding behavior, constituting an ethical decision.

CORRUPTION

Corruption becomes a matter of direct public interest when a government official accepts illegal remuneration for the benefit of the person making the payment -as some business people do- and has a negative effect on the public interest (Gámez, 2009). This phenomenon is present in all societies, and discussions focus on its progress in different countries. Markets and politics are not immoral per se, but as institutions they organize social practices from a moral standpoint that reflects pre-existing the values of individuals in each society, which are applied in each of these contexts (Andrew, 2012).

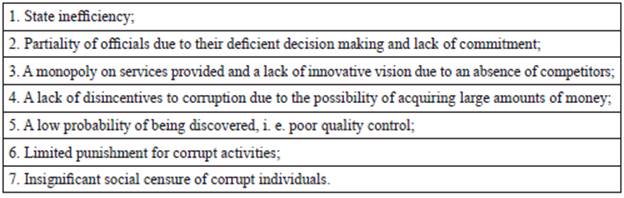

The emergence and consolidation of corrupt practices take place when society accommodates itself to them or affords them a level of acceptance. Corrupt practices are related to the long-term conditions in a society, the influence of values, the degree of influence exercised by the political system, the influence of the economy, and the dominant moral codes existing in each State (Gámez, 2013). Corruption includes the public or private misuse of power (see table 1) and a benefit to an individual or his or her family or friends (Transparencia por Colombia, 2014).

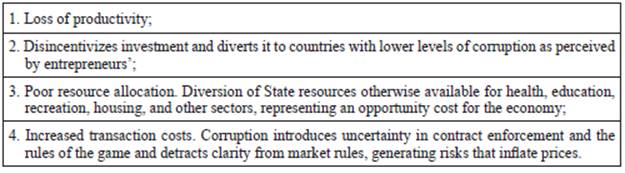

There are those who justify corruption as a mechanism for income re distribution in developing countries or an efficient solution to difficulties created by State intervention in the economy. The fact is, however, that its effects are expressed as additional investment costs (see table 2), reduced governability and transparency, compromised principles and values, distorted fiscal policy and tax collection, and difficult access to justice (Gámez, 2013). Vaca, Sepúlveda, and Fracica (2010) have found that entrepreneurs face market pressures coupled with pressures imposed through government policies, in addition to economic instability and company structures, forcing them to make decisions that are ethically misguided.

THE MOST COMMON ECONOMIC CRIMES IN COLOMBIA

According to kpmg (2013), the estimated cost of economic crimes in Colombia in 2013 was 3.6 billion dollars, i. e., 1 % of GDP. A survey of fraud in Colombia between 2011 and 2013, in which 197 managers of both public (35 %) and private companies (65 %%) operating in Colombia analyzed four types of economic crimes, including corruption defined as "illegal payments to public employees or employees of private companies in order to obtain or retain any personal benefit or to benefit a third party. These illegal payments are understood as bribes paid in cash or in any other form, including but not limited to gifts, travel, and favors"1.

Colombian entrepreneurs recognize that corrupt practices do exist and do affect them. These practices engaged in by "other" business owners range from illegal agreements on brands and prices, other forms of unfair competition, and money laundering and smuggling. Entrepreneurs identify with, recognize, and adapt to these practices since they feel that they have to live with them. In many cases they criticize corrupt practices but see no way to avoid them (Vaca, Sepúlveda, and Fracica, 2010).

According to Juan Ortega, director of DIAN until July 2014, just 3,500 regular taxpayers account for 70 % of taxes collected in Colombia, while the rest of the Colombian taxpayers contribute an average of only 3 million Colombian pesos per person. Tax evasion amounts to 6 billion pesos per year (Semana, 2014). Who avoids and evades taxes? According to Ortega: "There are clearly some organized crime groups, but they communicate with some real companies that occasionally evade taxes. Others are used and are victims. Some very serious companies steal their identities and import goods in their names" (El Espectador, 2014).

Colombia's tax collections amount to about 15 % of GDP, well below the 25 % of gdp needed by any functioning State and without which it is impossible to cover normal operating expenses, which is especially alarming on the threshold of a peace agreement (El Espectador, 2014). Evasion of the vat (Value Added Tax) is estimated by the IMF to reach 35-40 % (El Espectador, 2014a).

The criminal aspects of corruption must be considered, according to the director of DIAN: "I have systematically recommended criminal law reform. It is unacceptable that tax evasion is not considered a crime in Colombia" (El Espectador, 2014b). One economic measure to decrease tax evasion and avoidance is to have more people declare their income. For this reason, more than two million people with income greater than 3 million pesos per month will have to declare as of August 2014.

This is because some businesses write contracts for supposed workers and declare that they pay them inflated or undelivered salaries. Sometimes the people mentioned in these contracts never even know it. These sums are recorded by the businesses as expenses in order to reduce their tax burdens (El Tiempo, 2014).

ETHICS IN COLOMBIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

Higher education provides opportunities for reflection on ethics and business practices, and the Ministry of Education has plans to incorporate labor and citizenship skills in the training of future professionals. This will include implementing practices to combat corruption by teaching competencies for honesty and transparency in the management of power and resources, both public and private (Guerra, 2011). In their research, Hernández, Silvestre, and Alvarez (2011) sought to determine the importance of incorporating business ethics into the curriculum of business management programs. Training provided at universities may be able to provide the expected added value so important to both business organizations and society. Moreover, students must be taught how to seek and obtain benefits without sacrificing the social dimensions of the decisions made in the firms they manage. Graduates must be able to analyze and make ethical decisions when doing business (Hernández, Silvestre, and Alvarez, 2011).

Anderson and Smith (2007) have demonstrated the relationship between entrepreneurship and ethics. Although in the past it was thought that economic activities and non-economic social relations were naturally related, it has now been seen that economic development and moral purposes have moved away from each other due to an emphasis on profitability.

Llano and Llano (2004) show how moral deterioration in society is reflected in business behavior. This is why a business must be a kind of community, based on the personal values of its participants, while encouraging their personal development in the exercise of their professions. In short, cultural and moral relativism cannot be curtailed merely with the formal establishment of a company code of conduct. Harry et al. (2011) analyze some issues involved in entrepreneurial ethics, social entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurship and society.

Finally, Batchelor et al. (2011) tested business managers, entrepreneurs, and business students with and without academic training in ethics, to evaluate the ethical behavior within each group, which group students considered more ethical, and which group students most strongly identified with (entrepreneurs or business managers).

ETHICS TRAINING IN SOME HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS IN BOGOTÁ

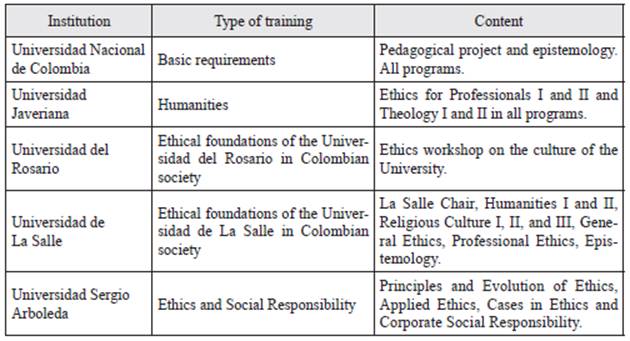

The quality of education can contribute to high rates of corruption in Colombia. Based on the introduction of citizenship competencies in primary and secondary education, it is considered essential to continue developing these skills at the undergraduate and postgraduate university levels, to avoid interrupting the educational process. One goal of today's educational approach is to train students in the cognitive, practical, and social aspects of education in citizenship competencies (Guerra, 2011), and some universities have integrated training in ethics into their programs (see table 3).

Table 3 Ethics Training at some universities in Bogotá

Source: Adapted by authors from information available on the web pages of the listed universities.

To some authors, Colombia is not a wholly corrupted State, because although accused or convicted government officials, judges, and legislators are engaged in moral pathologies, there is no institutional process through which the legitimacy of credentialing is being gradually eroded (García, 2012). In fact, the Colombian State is now at the best moment of its 200 years of existence. It has a constitution with the potential to construct a culture to act on its own to reduce corruption. In addition, acting to reduce corruption on its own opens the door to asking help from others (García, 2012). Indeed, the State is not on the decline, nor has it lost touch with the traditional values of the national culture.

METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

This is descriptive research intended to expose the important properties, features, and characteristics of the phenomenon of corruption in the private business sector. By virtue of the instruments used for data collection, it is a mixed form of research that combines quantitative and qualitative techniques. No causal relationship is proposed between the variables considered and the results, only concomitant relationships or covariations among variables (Garaigordobil, 2000).

For the quantitative analysis of data, a questionnaire with a Likert scale was designed to measure the attitude of entrepreneurs toward corruption in the private sector. Following the model of Blanco (2001) regarding the equilibrium and proportionality of items representing cognitive, affective, and behavioral components, variables were operationalized, crosschecking the categories that define corruption with emotional, behavioral, and cognitive components. The concept of emotion is intermediate between the empirical and the grammatical; people act in their totality within the environment. Primary emotions are Darwinian -adaptive, not cognitive- while secondary emotions are mediated by the ecological, economic, and political culture (Rodríguez Sutil, 2011). We attempt to identify the strengths and weaknesses related to these three components that characterize the population and could generate a greater or lesser predisposition to react to corruption in the business context. The instrument consists of a socio-demographic characterization of the population, and 15 items, each one associated with one dimension and one analytical category. Questions concern five categories of the company's activities: marketing, production, management, legal, and environmental. The dimensions are emotional, cognitive, and behavioral. When an individual condemns corruption, the value is closer to zero, and if the person approves corruption the value is 100.

The behavioral, cognitive, and emotional dimensions are determinative for an analysis of the results, allowing for an analysis of participants' reactions to each of the categories. The behavioral dimension can be understood as the action of a person in a particular situation. The cognitive dimension refers to the thoughts of an individual in reaction to a given stimulus, person, or situation. The emotional dimension is reflected in the feelings and biological reactions aroused in response to particular stimuli or contexts. Since the 1990s, there have been suggestions to include more analysis of theories of planned behavior, including emotion (Caballero et al., 2003). The emotions experienced and recalled in this research, however, are not predictive for future behaviors regarding business corruption, since the sample is insufficient for that purpose, and the secretive nature of corrupt behaviors presents substantial obstacles to the gathering of information.

Based on Dissonance Theory, which describes inconsistency in the thoughts and actions of individuals (Festinger, 1957), it is argued that that most entrepreneurs engaged in corrupt behaviors exemplify dissonance between ways of thinking and feeling versus actions. Despite his or her awareness of legal restrictions, a business owner may engage in corrupt behaviors. The goal of the research instrument is to identify, for the different categories of operationalization, which one or more of the dimensions increases predispositions to engage in corrupt actions in the business context.

The research includes expert perceptions, the perception indices of government agencies and international NGOS, and entrepreneurs them-selves (González Espinosa and Boehm, 2013). All questions required answers indicating absolute disagreement or partial agreement in order to qualify suggested behaviors. Other answers indicated support for corruption on the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions.

Procedure: A sample was constructed, consisting of entrepreneurs who had graduated from programs of higher education and other entrepreneurs who had not received any training in ethics. The criteria for selection of the sample were that I) companies must been in existence for more than 5 years by 2013; II) companies had to be independent and privately owned on December 31, 2013, and III) companies' registration with the Chamber of Commerce had to be active or had to be renewed on that date.

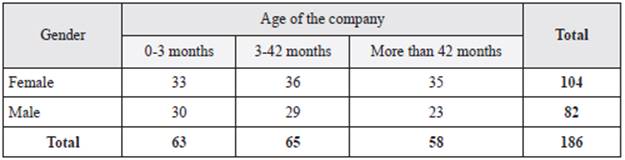

Variables (Man, Woman): In Colombia, more businesses are established by men than by women (Gámez, 2008). Age of entrepreneurs when establishing companies: Entrepreneurs in Colombia usually establish their businesses when they are between 25 and 35 years of age. Age of the company. Company formed by nascent entrepreneurs: Nascent entrepreneurs are those who have established enterprises in existence for up to 3 months, either self-employed or in combination with other work. New entrepreneurs are those who have established businesses in existence for a period between of 3-42 months, paying salaries or wages to an additional person or to the owner him or herself, either self-employed or in combination with other work. Established entrepreneurs are those with companies that have been in existence for more than 42 months, paying salaries or wages to an additional person or the owner him or herself, either self-employed or in combination with other work (GEM, 2011).

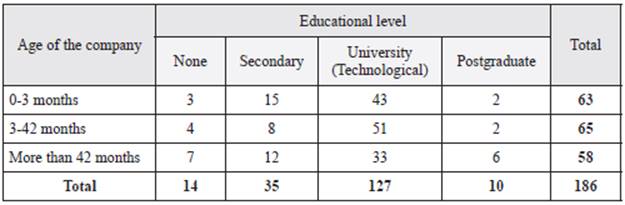

Sample: 186 entrepreneurs of both sexes from Bogotá, 17-52 years of age, with formal studies ranging from none to postgraduate.

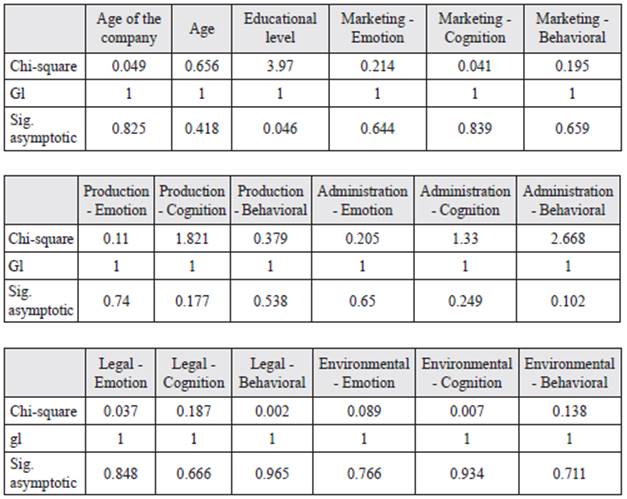

Data was analyzed using the Kruskal Wallis Test, which is a non-parametric test for comparing three or more independent samples. This test is analogous to the non-parametric Anova, and allows for a comparison of populations whose distributions are not normal.

Limitations: One limitation of this study is that full access by researchers to unethical experiences by entrepreneurs is impossible. Due to potential punishment -in many cases jail for both participants and witnesses- involvement in criminal acts of corruption requires that evidence be minimized (Caballero et al., 2003).

RESULTS

Human beings, including entrepreneurs, privilege certain values: power, achievement, hedonism, security, and benevolence (Hamburger, 2004). They modify these values in keeping with the degree of uncertainty that different environments offer them, including sufficiently clear environments, alternative environments, possible environments, and truly ambiguous environments (Serrano-Rincón, 2006). Social groups thrive in efficient environments and base their happiness on possession and options for maximization that may affect the performance of the companies they have established. These are the conditions under which market players operate and under which certain attributes are expected, including transparency (that their actions be open to society), without any type of hidden alliances, relationships, plans or secret projects behind the backs of stakeholders (Lozano, 1999).

Ethical decisions are not simple; they may have consequences with complex ramifications, and the business world and its context add more pressures (Trevino and Brown, 2004). The making of ethical decisions is related to the personal characteristics of individuals, including education, socialization in different roles, age, sex, and other significant factors including work environment (Stead, Worrel, and Garner, 1990).

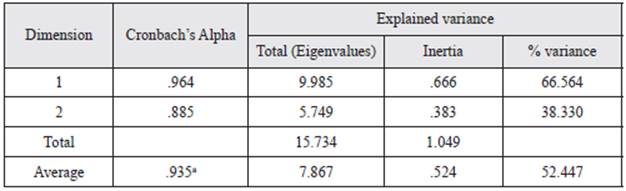

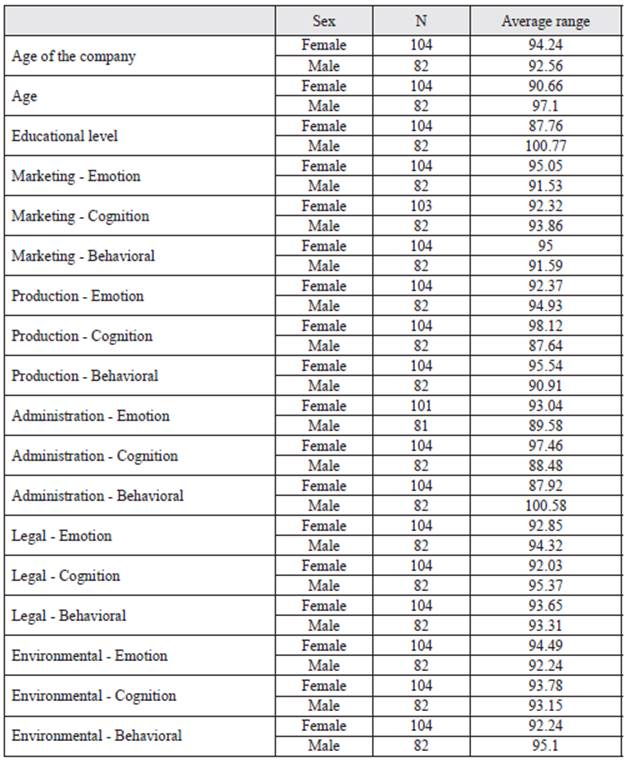

A Cronbach analysis is used to allow for the generation of relationships among qualitative variables, and Cronbach's Alpha Average is based on the average eigenvalues. In this case, these variables are sex, age, and educational level of entrepreneurs, and the age of their companies. A short description of the model brings to light multiple correspondences, as illustrated in table 1.

The two dimensions, or coordinates, of the solution explain the entire variance.2 Dimension one explains 66.5 %, and dimension two explains 38.3 %. Since the Cronbach's Alpha is .935, the multiple correspondence analyses is reliable. This means that the greater the proximity between the points, the closer is the relationship between variables.

The measures of discrimination show that most of the variables are more closely related to dimension one, with the exception of one variable, the age of the company, which is more closely related to dimension two. Expert opinion coincides with the findings, since more experienced entrepreneurs and those whose companies have existed for a longer period of time have adapted to corrupt behavior over time and tend to have assimilated to business customs and behaviors in order to ensure the survival of their companies. In addition, it can be inferred along with the experts that younger and less experienced entrepreneurs have little awareness of corrupt behaviors, but as they acquire this information and knowledge, they reject corrupt practices. This is the case among entrepreneurs with university and postgraduate studies, particularly the latter.

The variable of educational level produced very low scores, unrelated to any of the dimensions. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the few entrepreneurs who studied at the postgraduate level are aware of corrupt behaviors and flatly reject them. It can be inferred from the results of this study that the lower the level of an entrepreneur's educational achievement, the more likely it is that his or her cognition, behavior, and emotions will lead to corrupt acts, especially regarding environmental issues.

The diagram illustrates a clear relationship of people who totally disagree in the following variables: Administration - Cognition; Administration - Behavioral; Administration - Emotional; Environmental- Cognition; Environmental - Behavioral; Environmental - Emotional; Legal - Cognition; Legal - Behavioral; Legal - Emotional; Marketing -Cognition; Marketing - Behavioral; Marketing - Emotional; Production- Cognition; Production - Behavioral; Production - Emotional; with people between 27 and 28 years of age, with postgraduate education, and to a lesser degree with companies that have operated for more than 42 months.

On the other hand, there is a clear relationship of the people in total agreement in the variables Administration - Cognition; Administration- Behavioral; Administration - Emotional; Environmental - Cognition; Environmental - Behavioral; Environmental - Emotional; Legal - Cognition; Legal - Behavioral; Legal -Emotional; Marketing - Cognition; Marketing - Behavioral; Marketing -Emotional; Production - Cognition; Production - Behavioral; Production- Emotion; with people 26, 36, 39, and 41 years of age without any formal education and to a lesser degree with companies operating for less than three months.

Other opinions in response to these variables are found among other age ranges and people who answered that their educational level was university level (technological), and those who responded "Don't know" or "No answer", in addition to companies operating for a period between 3 and 42 months, without distinction.

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF ENTREPRENEURS

The entrepreneurs in this sample began their business activity at early ages (78 entrepreneurs, amounting to 41.9 % of the sample, were between 17 and 24 years of age), and their characteristics in terms of experience and business skills were not promising. Two of them had no formal education; two others had secondary educations, 47 had university educations in technological fields, and eight of them had postgraduate education. There were 31 entrepreneurs between 35 and 52 years of age, 16.7 % of the population.

The entrepreneurs are mostly men (77 of them, or 41.4 %), of whom 9 have no formal education, 13 have secondary educations, and 47 have university educations -technological- and 8 have postgraduate educations. There are 31 entrepreneurs 35-52 years old, constituting 16.7 % of the population.

As for the age of the companies in this sample, 33 % were startups, 34.9 % were new companies with 3-42 months of operations, and 31.2 % were established companies.

It is notable that few entrepreneurs had advanced educations (see Table 5); this will likely be reversed as a result of the Fondo Emprender (Entrepreneurial Fund) program, which will include students and graduates of postgraduate programs, and as a result of university training programs in entrepreneurship.

a) Marketing

About 35 % of those without a formal education showed positive attitudes to corruption in marketing processes. Entrepreneurs with undergraduate educations (40 %) identified corrupt actions without showing negative emotions and feelings.

Categorization by educational achievement: About 80 % of business owners with postgraduate educations tended to reject corruption in marketing. The higher their level of education, the easier it was to identify corrupt actions through the expression of negative emotions. As their level of education decreased, corrupt actions become less clearly identified (undergraduate, 41.7 %; no formal education or secondary education, between 30-40 %). As for conduct, 35.7 % of business owners with no formal education approved of corrupt behavior.

By age of the company: It was the subjective interpretation of facts -not the facts themselves- that determined emotions People perceive and structure the world (cognition) and their emotions and behaviors are determined on that basis (Ramos et al., 2009). Nascent entrepreneurs (46 %) were those who most often expressed negative emotions in reaction to acts of corruption.

By Gender: Women (47.2 %) expressed positive emotions in response to acts of corruption. Men (46.3 %>) recognized corrupt actions, and women (42.3 %) approved of corrupt behaviors.

b) Production

By educational level: Entrepreneurs with undergraduate educations (32.3 %), no formal education, or a secondary education (20-31.4 %) and postgraduate education (70 %) had negative emotional reactions to corruption. 25.8 % of business owners recognized corrupt actions. Those who had no formal education approved of corrupt behaviors (78.6 %), while business owners with postgraduate educations disapproved of them (80 %).

By the age of the company: companies that had been in business for less time had higher rates of approval for corruption in the area of production; 42 % showed no negative emotions and 49 % approved of corrupt behaviors.

By Gender: Corrupt behaviors were approved of by 38.5 % of the women.

c) Management

By educational level: Entrepreneurs without any formal education did not show emotions associated with disapproval of corruption in administrative matters (35.7 %). Those with secondary and undergraduate education showed approval (20-30 %). However, 22.6 % recognized corrupt behaviors; 16.7 % did so partially, and 43 % did not.

By the age of the company: Entrepreneurs seem to recognize corrupt acts at early stages of their businesses (0-3 months), but seem to forget them as they adapt to the market and its behavior. These responses point to a business system of winners and losers, in the words of Revenga (2007), as they adjust to a social cartography of the privileged and the dispossessed, of wealth and poverty, power and powerlessness, freedom and restriction.

By Gender: Men (35 %) and women (32.7 %) showed positive emotions in this area. Men (50 %) support corrupt behaviors in administration.

d) Legal

Laws and the observance of laws by business owners provide the ideal setting for humans to obtain what they value and the freedom to do so. The legal system also provides entrepreneurs with the opportunity to humanize the economy in order to enjoy an improved quality of life.

By educational level: Only entrepreneurs with postgraduate education expressed negative emotions towards corrupt behaviors (80 %). The lower their level of education, the more positive were the emotions that they expressed toward corrupt behaviors. (University graduates showed 34.6 % approval, secondary school graduates 37.1 %, and no formal education 50 % approval). The recognition of unethical conduct was progressively greater in keeping with their level of educational achievement (60 %), as was their approval of ethical behaviors (80 %).

By age of the company: the owners of companies operating for 3-42 months seemed to be uncomfortable with corrupt behaviors regarding legal matters (34.5 % and 34.7 %, respectively). Nonetheless, all interviewees seemed to be unaware of how to deal with legal matters regarding their businesses. (Entrepreneurs with companies operating for more than 42 months had the greatest knowledge of these matters at 30.6 %). It remains to be seen if the assertion by Stead, Worrell, and Garner (1990) can be justified in the sense that ethical profiles of entrepreneurs reflect past decisions on everyday matters.

By Gender: Women showed positive emotions towards corrupt behaviors on legal matters (46.2 %), as did men (44 %), seeming to be of the opinion that "We business owners should not feel bad for violating the law." Ignorance of legal issues is widespread, exceeding 45 % among entrepreneurs of both sexes. Our results coincide with the findings of Transparencia por Colombia (2014), and reflect the misuse of power for the benefit of business owners themselves or of their friends or family members. The recognition of corrupt practices in a business allows for the abuse of power and the betrayal of trust in order to obtain private benefit at the expense of the collective interest. It is possible that those who justify corruption may consider it a mechanism for income redistribution in developing countries or an efficient solution to difficulties created by State intervention in the economy (Gámez, 2013).

e) Environmental

Developing countries are more vulnerable to new environmental problems: increased water temperature, climate change, water quality, rising sea levels, and reduced availability of water. The results in this category allow us to infer that the higher the level of education among business owners, the lower is their apparent approval of behavior, cognition, and emotions related to corruption.

By educational level: Only 80 % of business owners expressed emotional opposition to corrupt company actions in the environmental sphere. In fact, 92.9 % of business owners without any formal education expressed emotions indicating support for company behavior that negatively affected the natural environment. It can be inferred that they are unaware of company impacts on the environment. 100 % of entrepreneurs without any formal education were unaware of environmental issues, and entrepreneurs participating in this research were generally unaware of environmental matters. It is noteworthy that no entrepreneurs without formal education were in disagreement with situations that negatively affected the environment. In contrast, those with postgraduate education were aware of the probable impacts of company activities on the environment.

By age of the company: Our results support the findings of Vaca et al. (2010) that business owners feel obliged by market pressures and company structures to make decisions that deviate from proper behavior. Entrepreneurs with companies operating for more than 42 months expressed emotions of support for corrupt behaviors (44.9 %). The nascent entrepreneurs were least familiar with environmental issues (41.3 %). Corruption in the area of environmental issues produces negative economic effects because it affects the Gini coefficient of inequality. Societies that do not actively participate in building cultures of transparency preclude the achievement of higher levels of equity and cultural rejection of corruption (Kliksberg, 2011).

By Gender: The emotions expressed in the environmental category did not reflect any significant differences between the sexes. Both sexes had higher rates of approval for corrupt actions in this category. This seems to suggest that civic education in all three dimensions should be strengthened in the areas of sustainable development and environmental protection.

EXPERT JUDGMENT

Experts Luis Enrique Orozco, Jaime Páez, Germán Montoya, and Javier Pombo all agreed that although one cannot generalize, some business owners participate in corrupt acts, regardless of their age, education, or the age of their businesses. Some entrepreneurs place economic interests above social interests, but experts stress the following:

Neither the impact of business owners on corrupt practices nor the extent to which corruption pervades their thoughts and actions has yet been measured.

Entrepreneurs have not been profiled with respect to their ethical behavior.

Entrepreneurs and their performance respond to rules that emerge from the environment.

The environment is polluted because values are not strongly imbued either in the home environment or in schools.

Entrepreneurs are not born corrupt. Over time, they accept the idea of corruption as a feature of normal behavior.

What did universities stop doing that used to produce young students who were good? When they graduate as professionals now, they are a symbol of national corruption.

Personal and professional success are measured by the possession of things and the desire to increase income more quickly and with less effort. This thinking may convince business owners to engage in unethical practices in order to achieve this version of success.

Education must be modernized as is being done in the business world and it must incorporate ethical topics more effectively than is the case in traditional programs.

Numerous scandals in Colombia, including corrupt contracting in urban development (carrusel de contratación, los Nule), price-fixing for consumer products (el cartel de los pañales, el cartel de los cuadernos), and corrupt investment schemes (Interbolsa) make it clear that there is a crisis of values in the business environment.

University graduates are very well prepared for entrepreneur-ship but lack a grounding in business ethics.

Universities have a responsibility for the business ethics of their graduates, but the role of the family, society, and the social environment must also be considered.

Jaime Páez indicates that among some of his students who have started businesses, the early years of their entrepreneurship were characterized by a frenzy to establish the company, to innovate, and to act ethically, but with the passing of time their ethical training faded from memory, their ethical approach waned, and they adopted unethical practices common in the business world.

KRUSKAL-WALLIS TEST

This research is not intended to analyze the study of the behavior as described in the theory of reasoned action (TRA) or the theory of planned behavior (TFB) because the predictive capacity of these models is even less adequate regarding questions of corruption (Caballero, Carrera, Sánchez, Muñoz y Blanco, 2003). When applying Cronbach's Alpha Test, the result was .935, showing a marked relationship between complete disagreement and ages 27-28, as well as postgraduate education. Answers in each of the variables show no strong relationship between total agreement and ages 26, 36, 39, and 41 or the lack of formal education. The variable "company creation", i. e. the age of company, has no connection with any of the remaining variables. This implies that it is only possible to see a negative attitude towards behaviors, thoughts and emotions related to corruption in the 5 categories.

In each of the observations analyzed, and using the Kruskal Wallis test, it can be established that there is not sufficient statistical evidence to ensure that none of the questions are directly related to the age of the firm.

In each of the observations, there is not enough statistical evidence after applying the Kruskal Wallis Test to ensure that none of the questions are directly related to the sex of the firm's owner:

DISCUSSION

Our aim in this research has not been to characterize entrepreneurs and corrupt practices directly, i. e. to try to measure a quality that cannot be observed directly among nascent, new, and established entrepreneurs. Corrupt behavior is not visible, first because there are not yet reliable psychological instruments for this purpose and second because corrupt practices are informal and illegal. Thus, three observable variables (cognition, emotion, and entrepreneurs' behavior) were evaluated for this purpose.

One limitation of this study is that the hypothetical cases that respondents reacted to involve a component of self-reporting of emotional experiences, and participants can rationalize the memories of their emotions, behaviors and cognition. Access to the experiences themselves is impossible since participation in corrupt behaviors is hidden from sight, and it requires a minimum amount of evidence (Caballero et al., 2003). This is not unrelated to the fact that acts of corruption are violations of criminal law, implicating participants and witnesses.

Corruption is a crime, so it is hidden and it is not easy to find someone who admits to having been involved. Measuring corruption based on the number of prosecutions, on the other hand, may generate distortions. An increased number of criminal cases involving corruption does not mean that corruption has decreased, that anticorruption measures are more effective, that authorities are acting more vigorously against corruption, or that there is increased political will to pursue it. The number of cases reflects the number of perpetrators who failed to consummate corrupt acts, but says nothing about the will, recognition, or intent to engage in such acts (González-Espinosa and Boehm, 2013).

What is required are direct indicators that can point to concrete acts of corruption, present obstacles, and monitor progress. Indirect indicators have been devised, based on the judgement of experts, national surveys and data provided by the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), Global Integrity, and Transparency International, including data on the costs and time needed to establish a business, on the functioning of political and administrative institutions, victim surveys, surveys of the private sector at the national level, public sector diagnostics, comparative price bulletins, reference price systems, report cards, and mirror statistics that compare expert opinion on what citizens perceive, among other things (González-Espinosa and Boehm, 2013).

The ability to measure corruption is limited by the low correspondence between the actual behavior of companies and the information they disclose. Along these lines, Cho and Patten (2007), and Cho (2009), cited by Aldaz, Calvo, and Alvarez (2012), found that companies with poor social and environmental performance, or that have experienced negative incidents, are more likely than other companies to spread positive information. This study indicates that large companies disclose information on corruption in various ways: by providing no information; by devising anti-corruption policies; and by implementing anti-corruption policies. Different types of business behavior can be distinguished: i) corporate culture (how firms communicate their principles to employees) ii) the implementation of management systems; and iii) the monitoring and control of corrupt practices.

CONCLUSIONS

This study indirectly identifies the attitudes of companies created by entrepreneurs who are university graduates toward the phenomenon of corruption in the Colombian business environment. Entrepreneurs of this sample have adopted corrupt behavior, mostly when they are less well educated and when new companies achieve stability. Entrepreneurs are most ignorant about company impacts -which is an incentive for developing corrupt behaviors- in relation to environmental issues. This work cannot predict corrupt behavior by entrepreneurs, but by learning about their attitudes, cognition, and behaviors, it enables us to infer that if there are no ethical correctives, businesses will continue to be perceived as participants in corrupt behavior.

The entrepreneurs in this sample started their businesses at early ages (78 entrepreneurs, amounting to 41.9 % of the total, were 17-24 years of age); 31 entrepreneurs were 3552 years old, amounting to 16.7 % of the total). Startups (3 out of 10 businesses) were established by women and men in similar proportions, but the difference in sex of entrepreneurs was more marked in relation to new businesses, where 19.4 % were women, and established companies, where 18.8 % were women. Regarding education, 7.5 % of entrepreneurs had no formal education, 18.8 % had secondary educations, 68.3 % had university or technical educations, and 5.4 % had postgraduate educations. As for the age of the companies in this sample, 33.9 % were startups, 34.9 % were new companies (3-42 months of operation) and 31.2 % were established companies.

People with less education showed positive attitudes towards corruption, and as the education of entrepreneurs increased, so did their rates of approval of corrupt acts and their consequences. It can be inferred that 54 of every 100 entrepreneurs with no formal education approved of corrupt behavior related to marketing-based processes in their organizations; that 40 out of 100 owners of businesses that have been operating for 0-3 months approved of corruption in production; that 30 out of 100 business owners with a secondary education did not distinguish between corrupt and ethical behaviors in implementing administrative models for their companies; and 35 out of 100 did not experience negative emotions in relation to committing unlawful acts or violating the rules of business.

Ethical behaviors by entrepreneurs and ethics in higher education

Ethical behavior depends on the environment, and a contaminated environment (such as in households where values education is weak and moral education does not lead to the adoption of social norms) leads some people to eventually accept corrupt behaviors, cognition, and emotions as normal and expected. Thus, not all entrepreneurs take the ethical demands of society to heart, and some of them do engage in unethical behavior.

Those who fight corruption, and how they do so

International anticorruption initiatives include the United Nations Global Compact. The Global Compact is a voluntary association that promotes the incorporation of ten principles into the activities that businesses carry out in their countries of origin and in their operations worldwide.

The Inter-American Convention against Corruption of the Organization of American States (OAS) focuses on public corruption. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has its Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions to resist transnational bribery, and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption fights unethical business practices in the private sector.

The Colombian Constitution sets out ways to prevent corruption with support from the Supreme Court, the Supreme Judicial Council, the Office of the Attorney General (since 1991), the Office of the General Comptroller, and the Office of the Inspector General. Transparency International, and its chapter in Colombia, suggests prioritizing corruption as a matter on the public agenda to overcome the vicious cycle of violence, drug trafficking, and organized crime as scenarios for corruption.

The cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions of business owners towards corrupt behaviors by education, sex and age of company

About 35 % of people without any formal education showed positive attitudes towards corruption in marketing activities. Entrepreneurs with undergraduate educations (40 %) recognized corrupt actions and did not express negative emotional reactions. Almost 80 % of business owners with graduate studies rejected corruption. As the educational level of entrepreneurs increased, it became easier to identify negative emotional reactions to corrupt activities, and as their educational levels decreased, it became harder for entrepreneurs to identify corrupt activities. Nascent entrepreneurs (46 %) were most likely to describe emotional reactions to unethical acts, but these reactions decreased with time. Women (47.2 %) showed a higher level of approval and fewer negative emotions when engaging in corrupt activities. Finally, 46 out of 100 women entrepreneurs accepted corrupt behavior in legal matters.

In the area of production, the entrepreneurs with positive attitudes to corruption were those with no formal education (21 %). 30.6 % of the interviewees approved of proposed corrupt actions, showing no negative emotional reaction, while (70 %) of entrepreneurs with postgraduate education disapproved of them. Regarding sex, it can be stated that more men showed a positive attitude toward corrupt behavior (40 %) than women (38 %). 25.8 % of business owners approved of corrupt activities, and twice as many entrepreneurs without formal education (50 %) approved of them. Only half of all entrepreneurs with no formal education experienced negative emotions regarding illegal acts or the violation of business rules.

In the area of management and administration, research on the emotional dimension indicated that 35.7 % of business owners without any formal education did not reject corruption. Data in the cognitive dimension showed that almost 30 % of those with a secondary education approved ideas that would justify corrupt activities, behaviors that met with approval from 21.4 % of business owners without a formal education. The trend in this area is for entrepreneurs with less education to approve of corruption at higher rates. More men reject the idea that entrepreneurs should not feel bad about engaging in corrupt activities in administrative matters. In fact, 40 % of entrepreneurs who had been in business for about 3 years approved of violating public and private rules in order to meet goals for business activity and their organizations' financial goals.

In the area of legal activities, almost 46 % of entrepreneurs approved of the absence of negative emotions.

About 36 % approved of ideas that justified corruption and 39 % approved of corrupt behavior. As the educational level of entrepreneurs increased, the rate of approval for corruption decreased, with 37.1 % approval among secondary school graduates, 34.6 % approval among university graduates, and 10 % approval among entrepreneurs with a postgraduate education. Men (44 %) did not express negative emotions toward corruption in legal contexts that could be expressed with the statement "Business owners should not feel bad about breaking the law", while women disapproved of the statement (40 %). Finally, 46 % of women would accept corrupt behaviors, as would 41 % of men.

With respect to the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components of entrepreneurs' approach to the environmental activities of businesses, entrepreneurs were more tolerant of corruption, and 38.7 % of them did not express negative emotions toward corrupt acts that threatened the environment. Business owners without any formal education were those who most frequently approved of the absence of these emotions (92.9 %), and none of the entrepreneurs without any formal education were unaware of such activities' impact on the environment. Only 23 entrepreneurs would act to benefit the environment. Corruption affecting the environment had a direct relationship with the level of education of business owners in Bogotá. The lower their educational level, the more likely they were to engage in behaviors that were harmful to the environment. In fact, 78 % of business owners with no formal education accepted and approved of corrupt behavior affecting the environment.