1-Territorial implications of large scale urban interventions and their internal contradictions

"The metropolitan area of Bilbao (Bilbao Metropolitana) is formed by the City of Bilbao and several surrounding municipalities. In 2005, the City of Bilbao had 350,000 inhabitants and the metropolitan area 900,000 inhabitants. Of the province's population of 1.15 million, 80 per cent live in the Bilbao metropolitan area and a third in the City of Bilbao. Bilbao is not only the most important Basque city; it is also the largest agglomeration on Spain's Atlantic coast and the sixth largest metropolitan area in Spain" (Ploger 2007:4).

The city, located in Northern Spain, suffered in the 1980's from a series of problems that intensified the need for regeneration. Amongst these issues, was the closure of the steel industry along the river, the loss of the city's status of capital of the Basque Country in favour of the city of Vitoria when democracy arrived in Spain in the late 1970's, high unemployment, population loss and armed conflict relating to the Basque separatist group ETA (Euskadi ta Askatasuna). If we take this into account, Bilbao was not only left with a legacy of socio-political problems but also with a very contaminated river that split the city into two sides; the left (traditionally working class and with high unemployment after the industries' closure) and the right (the bourgeoisie that were originally part of the commercial and economic powerhouses of the city); in addition to this the brownfield sites along the river were in desperate need of urban regeneration. These zones were affected by high contamination, lack of access and different types of ownership but in spite of all these problems they were also seen as areas of opportunity. In order to regenerate them the demolition of the existing industrial infrastructure was required to attract new types of economies and investments. This radical approach is twofold as on the one hand it is "a drastic position even iconoclastic with respect to the conservative attitude to keep any vestiges of the industrial past" (Leira, 1994:69) which allows Bilbao to be re-born from its ashes like an Ave Phoenix and re-write urban history; but on the other hand the industrial heritage was destroyed to allow new buildings to emerge in these locations (without any reminiscence of the architecture that represented f the steel and ship building industries along the river).

The process began with a competition for a new Guggenheim Museum on the banks of the River Nervion that was won by the Canadian architect Frank Ghery who actually put the city of Bilbao on the map, and created the concept known as the "Bilbao Effect". The creation of this icon which became one of the most photographed images in recent architectural history led to a new approach to urban regeneration based on this concept of using an icon to sell the new Bilbao. As part of this process "Key sites along the river banks were identified as opportunity areas. The regeneration of designated 'opportunity areas' was carried out by Bilbao Ría 2000, which invested a total of €560 million between 1997 and 2006. Initially, the territorial plan identified four such 'opportunity areas' (Abandoibarra, Zorrozaurre, Ametzola and Miribilla) (Ploger,2007:22). The museum was located on the site of Abandoibarra in the heart of the city and at the end of the ninetieth century expansion but topographically was about ten metres below ground from the rest of the city which meant there were issues with permeability and connectivity with the rest of the urban fabric. The museum was also the beginning of the economic regeneration and the development of the tourist industries in the old industrial city. The Museum is not just an object or an icon but it also engages with the urban fabric of the city as "The subterranean entrance to which should be viewed as far as well as near, is in direct alignment with a major artery, that bisects the city, ending at Bilbaos' main plaza. From the atrium, another flight of stairs guides visitors to the sculptural tower, which integrates the Puente de la Salve (bridge) and provides a public path into the centre of the city" (Klingman, 2007:242). This point is also emphasized by other scholars and the importance of this effect is not just for the image of the city but also for its financial implications: "Frank Ghery's New Guggenheim, cost $100 million and in two years brought $400. This 'Bilbao effect', was not the first use of enigmatic signifiers as a landmark, but it was the most effective. Note the way in which the building engages with the total landscape-the industrial elements and bridge, the Nervion river, and the hills on both sides of the river" (Jencks, 2006: 5). What is most successful is the remarkable regeneration of the river, the public parks and walks that open up Bilbao to the river Nervion. The regeneration company Bilbao Ria 2000, and its innovative approach to public-private partnership has certainly influenced the success of these interventions (including big infrastructure projects such as Foster's tube system, and Calatrava's new airport and the interventions of freeing up space by putting both railway and roads underground to bring the civic public spaces back into the city)

This large scale urban project did not just regenerate an area of the city that was left abandoned, but it also became a phenomenon that other cities of a similar size wanted to copy, particularly the idea of using an icon to put their city on the map The regeneration process in Bilbao's Abandoibarra site was completed in conjunction with a series of other grand interventions around the river, the Isozaki residential towers, the Calatrava bridge, the new Euskalduna palace by Federico Soriano, the shopping mall Zubiarte by Robert Stern, two buildings by architects Rafael Moneo and Alvaro Siza, and the highest skyscraper in the city, the Iberdrola Tower by Cesar Pelli.

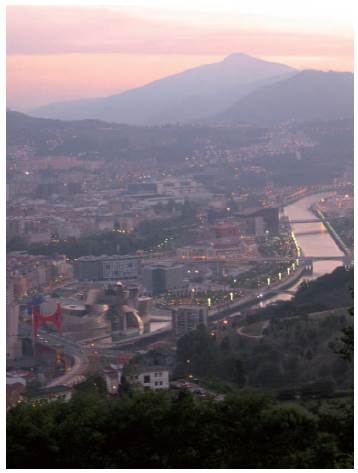

Image 3 The Abandoibarra site with the Euskalduna palace at one end and the Guggenheim Museum at the other and in relation with the 19th century expansion of the city

Some of the iconic buildings are more integrated with the city than others;, however what is clear in the case of Bilbao, is that the infrastructural interventions of cleaning up the river, improvements to the transportation infrastructure in the city and the innovative approach taken by the regeneration agency Bilbao Ria 2000, makes the iconic projects work together in the different brownfield areas. The buildings by themselves would not just work in the urban context without the other urban elements (the river, the connections, and improvements of public realm).

One of the internal contradictions with this large scale urban intervention is that the icon concept was replicated too many times at the site, without really considering its immediate surroundings, ending up with too many icons on one site without any of them being a clear landmark or really integrating as much with the site and the river and the fabric of the city as the Guggenheim museum did when it was built. There is a saturation of icons in one site to the exclusion of the industrial heritage that was once there. It has indeed been wiped out to allow the grand projects to emerge. Maybe revisiting some of the small structures that were there would have led to different types of considerations and directions in the development of some of these sites and their specific agenda. To me this is one of the main contradictions inherent in this process: "its conventions teeter at the precipice of saturation, leading us to this seemingly strange proposition: Architecture can no longer limit itself to the aesthetic pursuit of making buildings; it must now commit to a politics of selectively taking them apart" (Stoner, 2012: 1).

I think that observing some of the infrastructures left on the river from the old industries of the city could offer the opportunity of developing new design agendas that use small objects for the regeneration of these sites to provoke new types of thinking and approaches different from those proposed earlier in Bilbao, that although putting the city on the map also took away the industrial reminiscences that were part of its history. In my view this type of new thinking is necessary not just in Bilbao, but in many other cities around the world with similar issues and dilemmas about their urban regeneration.

2- Urban re-structure and the conflicts created by real-estate/land value increases in urban space

The urban restructure of this area of Bilbao meant there was an increase in real estate and land value. The museum itself was a success "While the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao was a costly venture, its return on investment (not including the value of the permanent art collection) was recovered in the first seven years following its inauguration. Figures show that since the museum's opening, the city has received an average of 779,028 new yearly overnight stays and has created 907 new full-time jobs. GMB earns around $39.9 million annually for the Basque treasury" (Plaza, 2007:16). The increase in land value, of what was originally an industrial site, translates into a lack of affordable residential property for the local population on those sites. It also means that investment is focused mainly on opportunity areas, leaving other parts of the city without any improvements over a long period of time. A gentrification process then occurs in the sense that while employment and benefits of these interventions are clear in terms of financial investment returns in the tourist industry, it also means a clear lack of inclusion of the local population in some of these processes or their ability to partake in some of these projects. A flat in the Isozaki towers (one of the few residential projects) in the Abandoibarra area ranges between half a million euros to seven hundred thousand euros1 which is possibly one of the highest residential prices not just in Bilbao but in Spain. This intrinsically means that the local population that once lived near these areas could not afford to live there anymore and has had to move to other parts of the city.

3- Political agents and actors that shape the urban transformation agendas- Public and private partnerships

The political situation and varied ownership of the brownfield sites along the river Nervion, meant that, in order to develop them, an agency had to be created with autonomous powers to preside over the development of these areas.

"In December 1992 the Basque government and the central administration reached an agreement to create a development corporation for the regeneration of metropolitan Bilbao. Most of the land for development was located on the left bank of the river. Ownership over that land belonged to public firms like Renfe (national Railroad Company), INI (the national institute for industry), the port authority and the ministry of public works, transport and environment (MOPTMA): all of the land that was owned by these corporations was a potential redevelopment site.

The agency for regeneration is Bilbao Ria 2000. Its main aim is to manage large-scale revitalisation of abandoned land formerly occupied by harbours and industry or by obsolete transport infrastructure. Its aim is 'producing new opportunities from old problems,' and its objectives are to recover, communicate, transform facilitate and improve. The agency is a public limited company in which local and regional institutions and the Central government each have a 50% share. The mayor of Bilbao chairs the company, while its deputy chair is the Secretary of State for Infrastructures and planning of the Ministry of Development. The partners allocate land to the company to be redeveloped. The company is an NPO (Non-Profit Organisation) and any financial gains are re-invested in the areas themselves or other town planning activities" (Holm & Martinez-Perez, 2009: 20-22)

This type of partnership consisting of both public and private investment has allowed FOR development to occur slowly and in a very successful manner. The structure has different tiers of regional and national government that allow for agreements at those political levels to happen without too much bureaucratic apparatuses interfering. Another aspect of this type of approach is the fact that sites that have multiple ownerships are under one umbrella; this factor facilitates the process of urban regeneration by unifying the clear up of the brownfield land, the creation of basic infrastructure and the marketing and selling of parcels to developers.

As the Director General of Bilbao Ria 2000 Angel Maria Nieva explains reflecting back on the last few years:

"It was therefore decided to implement a radical plan of action for the strategic area next to the river. The first action would be the systematic demolition of the old industrial, railway and port installations that had become obsolete and, from that point onwards, the complete re-urbanisation of the river zone between Bilbao and the river's mouth to the sea in Abra bay. Together they occupy a total of almost 600 hectares of strategic land that is ideal for conversion into the highest quality areas of the metropolis, with the possibility of gaining almost twenty kilometres of waterfront (ten on both sides of the river)"(Gobierno Vasco, 2002: 160)

However there are some critical voices to that success specifically in relation to the Abandoibarra site: "The project, the most iconic of contemporary Bilbao, lacks the phases and structure of the 19th century expansion and above all it has forgotten the encounter of the city with its river"2 (Cenicacelaya, 2004:27).

It is clear that the history of Bilbao's regeneration project has been a very successful one, attracting global attention and clearly also investment. However as a result of the gentrification processes that ensued, there has been an increase in the real estate values of the sites. Also the industrial heritage has not been kept but has been replaced by iconic buildings without taking into account the genius loci of the place. While some elements of the design of these iconic buildings might relate to the site, there is a clear disconnection between the Abandoibarra site and the general fabric of the city.

Another aspect is the rise in value of residential land use that occurred as a result of the Abandoibarra regeneration, becoming now one of the most expensive areas in the city to live. You can question the elements of urban regeneration tools and their success, when only a few are able to afford to live in the exclusive Isozaki Towers, and more recently we are yet to see how much success will the Garellano project by Richard Rogers have in terms of housing provision, and also in relation to this area of the city.

However the regeneration of the river has brought a clear new public space to the city and opened the city up to the water.

The real challenge seems to be with what will occur at the remaining brownfield sites along the river.

This poses interesting questions as a different approach, as I mentioned earlier in this article, could be sought that incorporates the development of the existing structures into the general masterplan for these sites. It is clear that the economic benefits of the Museum and the urban regeneration brought to the city a new tourist industry changing the face of what was an industrial city, into a services one. However with the current crisis and the economic situation in Spain, the history of this success remains to be seen in social terms with unemployment rising and consumerism decreasing. The city's economic crisis can not only be resolved with a new emerging tourist industry but with much more consistent programmes of economic development that include both job generation and housing provision and not just urban interventions. The crisis also opens up new opportunities in thinking if the iconic approach and the effect that it generated are models we can rely on, as they are dependent on real state values, and investment.

The interesting point about Bilbao is its application to similar cities which are not capital cities, but to medium size ones with similar socio-political problems to turn their destiny around and to use different forms of public-private partnership to be able to achieve their urban regeneration.