Introduction

The early XXI century witnessed the historical moment when over half the world's population became urban. Such urban agglomerations are currently the backdrop of the most diverse and significant processes, including economic development, cultural integration, social welfare and environmental conservation (Pinto, 2001). While in the XX century, metropolises were the great urban developments capable of organizing the new economic and social setting arising from the industrial revolution, "global cities" are currently organizing the events of a new productive and economic phase - advanced capitalism and its impact on a globalized world (Harvey, 1998; Sassen, 1991).

In general terms, "global cities" are characterized by the economic, political and cultural ties they offer between the local economy and the world market. Their activities focus on specialized and high technology services (advanced tertiary sector) rather than on industrial activities. These cities concentrate on leading technology industries, transnational corporations and a significant part of the financial sector, which establishes them as holders of large financial resources and, therefore, provides them with influence in the global economic and social order (Cox, 1995; Sassen, 1991). This urban condition, in evidence over the last 20 years, has sparked new metropolitan urban planning concepts and methodologies. Large cities should attempt international integration -an essential condition for survival in a post-industrialization era- in addition to meeting the complex needs of local urban conflict resolution. The "plan", which once aspired to resolve physical and social impasses, has been replaced by "strategies" toward turning local physical transformations into publicity capable of attracting national and foreign economic investments (Montaner, 2009).

Thus, since the 1980s, "accidental cities", created by favorable geographical or natural conditions, transformed into "intentional cities", designed to reduce threats and maximize opportunities, seeking a vision of the future supported by society in a mutual effort (Hanson, 1984). Similarly, urban planning, within a "plural world-wide global society" (Clark, 1996), sought an identity at each intervention area and a manner to project such an image worldwide. Thus, through a "global economy of the network society" (Castells, 2009; Lopes, 1998), one of the main goals of global cities is competitiveness to "meet the global demands and attract international financial and human resources" (Borja and Forn, 1996: 36).

Cities begin to ensure their relevance through the transformation of space into a showcase, given this need to compete for their "image", which leads to striking consequences in their planning and development. The city is thought of as a product and as being marketable (Benach, 1997). Cities usually excel in the context of global competition if the display form and content are well defined in the marketing strategy. In Brazil, there were two significant actions in this process, according to Vargas and Castilho (2009). The first, real estate capital, created prime locations and prompted demand through supply. The second, local government, sought to enhance the city's positive image to attract foreign investment toward urban economic development. Together, they adopted market planning (Ashworth and Voogd, 1990) and introduced techniques for promoting cities.

Such institutional mechanisms for promoting and selling cities is known as city marketing. The emergence and rise of this process also indicate the emergence and rise of a new planning and action ideology, a new worldview guiding these policies (Ashworth and Voogd, 1990; Sánchez, 1999).

This process has a strong effect on city planning, given the ease with which this tool incorporates new information and communication technologies (Sánchez, 1999). Furthermore, actions are performed for the renewal of urban landscape and its social structure through ties with new political and social representations.

According to Sánchez (1999), the valorization of city marketing would also result from the economic situation of countries based on neo-liberalism, whose consequence would be an increasingly unstable state of urban centers and their development models, functions and morphologies. Thereby, a steady increase in the levels of competitiveness between different locations and respective sectors (areas, neighborhoods) of a city would be reached not only by enhancing the local dimension in the context of globalization but also by adopting (neo)-liberal free market formulas. In this context, the operations of investment and speculation of financial capital would regard cities as investment opportunities if an expectation of future earnings (profits) could be generated.

In the last decades, culture has been used as one of the main urban intervention, planning and policy strategies of city marketing actions. The model, which gained importance in the 1990s in Europe (in cities such as Barcelona, Bilbao and Lisbon), gradually reached Brazil due to the pace of its recent economic development. Various urban designs, plans and policies using culture as a catalyst for investments and popular support were spread nationwide. Whether dealing with the preservation of historical sites, occupation of degraded or vacant urban areas, revitalization of central or peripheral areas or even urban expansion, the emphasis of interventions has been on rehabilitating or recreating historical settings, building striking cultural facilities, carefully designing public spaces and using public art and cultural animation, among other features. The results of this "cultural regeneration" (Wansborough and Mageean, 2000) are not always encouraging and have been criticized and discussed in the fields of architecture and urbanism, social planning and social sciences (Arantes, 2000).

The authors chose to analyze the impact of cultural buildings in a specific and iconic area of the city of São Paulo, given the complexity of the city's relationships and processes, the scale of its numbers and the impossibility of studying it individually with the necessary depth in a short period. Therefore, the current study examines the region of bairro da Luz (Luz district), one of the main areas of the city's historic center. The study aims to answer the question: Was the city marketing policy, through buildings with cultural programs, successful in the rehabilitation of its surroundings in Brazil, specifically in the center of São Paulo? The proposal for the Complexo Cultural Teatro da Dança (Cultural Complex-Dance Theatre) of São Paulo, a mega architectural and urban enterprise designed by the famous Swiss office Herzog & De Meuron, will be the study object.

City marketing

City marketing is a branch of strategic planning aimed at promoting cities to make them more appealing and competitive to investors. This approach to understanding and planning a city as a "commodity" (Ashworth and Voogd, 1990) has been intensely widespread from the 1990s and is observed in the development and planning of a significant portion of large or touristic cities worldwide. According to Sánchez (1997), these strategies have gained a key role in all new urban policies, and "their emergence and rise [...] also indicate the emergence and rise of a new planning and action ideology, a new worldview guiding these policies" (Sánchez, 2003: 26).

One of the main features of city marketing is the use of "culture" as an essential tool to enhance competitiveness and publicize the urban image required to promote a city. Developing recreational and cultural activities in institutions such as museums, galleries and theaters, among others, festivals and a fun shopping business environment results in a "cultural urbanism" (Meyer, 1999a). Architecture, as we shall see, becomes an essential tool to create a publicizable and marketable city image.

According to the literature (Ashworth and Voogd, 1990; Kavaratzis, 2004; Kavaratzis and Ashworth, 2007; van den Berg and Braun, 1999), it is possible to conclude that the main tools of city marketing are the following: i) iconic architecture, ii) emblematic events, iii) "brands", iv) speech/slogan/logo and v) public-private partnerships.

These tools are interdependent; that is, combinations of these tools should be used, relating one topic to another for city marketing to be effective.

Architecture and city marketing

Architecture has been used as an icon or symbol since the beginning of civilization. Icons have changed from natural elements (rivers, valleys, mountains) to buildings, and subsequently, another transition occurred that would complement the previous trend, wherein icons were also monuments and symbols, among others (De Melo, 2005). In Egypt, the pyramids (mausoleums) were used as a means of demonstrating their owners' power. In classical antiquity, the Parthenon in Athens (Greece) and the Coliseum in Rome (Italy) are examples of architectural icons. The former denoted the importance of the civilization it represented given its location atop the city's highest mountain in addition to being a religious center of attraction, while the latter was a meeting point where society gathered to attend Emperor-led events. In the Middle Ages, cathedrals were important for their monumentality and helped bring new urban structures to cities. Historians also report that architects had a prominent place in the political life of public administrators, both for providing great visibility through monumental works and for their notoriety, as exemplified by the positioning of architects on the Pharaoh's right-hand side at events and meetings (Mendes, 2006). This political importance -from kings and emperors in antiquity to presidents and mayors currently- also denotes a sense of the need for architectural icons designed to esthetically assert governments and states and their accomplishments (Hazan, 2003). Such proximity between political and esthetic interests does not always benefit the needs of the majority of the population. According to Henri-Pierre Jeudy (cited by Hazan, 2000) esthetics is perhaps closer to politics than ethics; it cannot be at the service of politics but can provoke political discussions.

With the large increase in metropolises and the globalization process, cities become increasingly uniform, precluding personal identification with the place of residence or visit. Such a concept was widely publicized by Koolhaas et al. (1998) with the term "Generic City".

City marketing seeks to turn "urban icons" into elements that reveal (or create) a local identity to ease this process and encourage cultural and historical uniqueness. These icons can be of large scale, including the "visual accidents" reported by Cullen (1971), or of a smaller scale (monuments, landmarks, viewpoints, among others) with a specific characteristic. These elements, according to Lynch (1960), may enhance certain features of the site or may be unnoticeable, contributing a visual disintegrator that prevents the perception of the unity of the physical and mental image of the environment. Therefore, according to Cullen (1971), readability is enhanced when visual and functional elements are enhanced considering two fundamental characteristics: contrast and innovation.

Innovation is a key topic in city marketing policies; however, what is currently observed is a "homogenization" of architecture, whereby architects design their projects without considering local cultural characteristics but rather focus on the search for global esthetics. Dubai is, currently, the most significant example of this type of artifice.

The city as commodity

As reported by Sánchez (1999), the city marketing process and its effect on planning depend on the ease whereby this mechanism incorporates new information and communication technologies, which, through connection with new social policies and representations, affects the renewal of space forms and leaves a mark on the urban space. This space production has many benefits, including attracting investments and people, increasing tourism and structural and esthetic development. However, the negative aspects of these actions must be investigated such that in the future, the city marketing tools, when revised, can be used for the benefit of the population and to improve their performance regarding the city as a whole.

In summary, concerning city marketing tools as a mechanism of city development, the following issues can be highlighted: i) PPPs wherein private interests prevail over the population's, ii) excess spending on "iconic architecture", iii) the development of "urban settings" of little use to residents, iv) gentrification and v) the weakening of local culture and traditions.

Another characteristic of city marketing is the appreciation of "iconic architecture", that is, works designed as major formal milestones in the structure of the territory. These monuments almost always represent political or economic yearnings and result in the design of settings inconsistent with the population's real condition. Public spaces previously intended for social exchange, the real space lived in, become the representation of an artificial space, detached from residents and users, as it was designed in one go, without considering the local traditions and identities (Harvey, 2000; Lefebvre, 1998; Smith, 2009). There is "a mismatch between the symbolic appropriation of modernized spaces and the effective appropriation of the products of modernization, with inclusions and exclusions driving social uses" (Sánchez, 2003: 34). Thus, as reported by Lima (2004), there is a dramatization of public life, which excludes the native population of these spaces regulated by government and corporate interests. This process that "incorporates and simultaneously conceals: social relations and how these relations occur" (Lefebvre, 1998: 81) drives that population away, both horizontally (to suburbs) and vertically (to other levels of land).

In the last decades, there have been numerous examples of cities that have adopted "cultural" or "creative" functions to give meaning to architectural monuments of billionaire budgets that are often of little use to the local population.

Luz district, São Paulo

The Luz district was one of the strongholds of the first factory system of São Paulo, whose popular profile was already evident in 1867, when received a great urbanizing boost with the implementation of the São Paulo Railway. The new physical configuration gave rise to the so-called "working class neighborhoods", with a "working village" residential architectural typology.

From the 1870s onwards, São Paulo began replacing its colonial setting, opening up to an "embryonic metropolitan cycle" (Morse, 1970).

Image 1: Luz district. Street near the Julio Prestes Station. Photo: Eduardo Costa and André Kobashi 2011.

Since the early decades of the XIX century, in the bordering streets outside the commercial concentration promoted by developers, the government installed a highly prestigious facility, Jardim Público da Luz (1825). Subsequently, Estação da Luz (1825), an urban sector committed to the city's metropolitan destiny, was created. Adjacent to Estação da Luz, commercial and hotel facilities were created that transcended, ever since their inception, the strictly local demands.

The Plano das Avenidas [Boulevards Plan] was drafted in 1930 by a Prestes Maia engineer originally seeking a systematization of the road network by creating a new structure for the center. "Although the proposal [... ] emphasized the central area roadway issues, the physical organization of urban functions related to circulation and accessibility rather exceeded this limit" (Meyer, 1999b: 24). Throughout the following four decades, the installation of a metropolitan level structure was based on the model proposed and implemented since 1930, including the design of the ring road, the delimitation of radial roads and the north-south cross-sectional road axis.

The process of decline remained unchanged despite the transfer of activities from Central Bus Station to Terminal Tietê (new central bus station) (1982) and the first subway line (1974) with the Luz Station. The index of "slum tenements" increased, and drug trafficking activities in the neighborhood streets began.

Thus, from the 1970s, Luz district became the object of interventions, both in specific projects and in its area being included in several projects. E.g.:

The creation of a Preservation and Recovery Zone (1974).

The Cultural Luz Project (1984).

The programs Centro Seguro (Safe Center) and Ação Local (Local Action) (1991).

The São Paulo Centre - Urban and Functional Re-qualification Program (1993).

The Operação Urbana Centro (Urban Center Operation) (1997).

The Pólo Luz Project (1998), from which the renewal of Pinacoteca do Estado (museum), Julio Prestes Station (transformed into a São Paulo concert hall) and Luz Station resulted.

The Monumenta/BID (2000).

The Nova Luz Project (2005).

And the Portuguese Language Museum (2006).

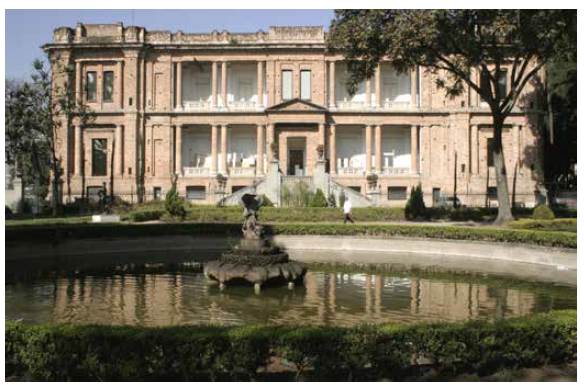

Image 2: The Pinacoteca do Estado Museum, situated in Luz district. Designed by architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha (Pritzker Prize 2006). Photo: Eduardo Costa 2011.

Despite the effort in drawing connections for the region, the fragmented process of urbanization (a result of land ownership characteristics) generated an urban mesh that was discontinuous and largely inefficient. This process of unsatisfactory integration spanned the entire twentieth century with no solution.

In this study, the focus is on a recent intervention in Luz district: the Complexo Cultural Teatro da Dança (the Cultural Complex-Dance Theater).

São Paulo's Cultural Complex-Dance Theatre

The purpose of the Cultural Complex-Dance Theater is to be one of the country's most significant centers for the performing arts, specifically designed for dance, theater, musical and opera performances. The implantation site, at Luz district, encompasses the quad formed by Júlio Prestes Square, Duque de Caxias Avenue, Rio Branco Avenue and Helvética Street. The land area is 37,000m2 (approx.), and the floor area is 90,000m2 (approx.).

Image 5: Old bus station demolished. On site will be built the Dance Theatre. Photo: Eduardo Costa and André Kobashi 2011.

First, the State Secretary of Culture commissioned the British company TPC Theatre Projects Consultants to define the profile of the future complex and detail the program of each item. Their technicians studied and analyzed the city to scale a theater of unique features.

Based on this study, the Secretary selected international offices of architects who might be interested in developing the project: the English Norman Foster, the Argentine living in the USA Cesar Pelli, the Dutch Rem Koolhaas and the Swiss office Herzog & de Meuron. "We wanted notables", confirms João Sayad, the Secretary of Culture (Miranda, 2008). The selection mainly considered that these offices are "negotiators and flexible". "They have to subject architecture to theater quality. There are many works out there that have been harmed by the architectural shape. We did not just want a theater turned sculptural work". Another criteria proposed by the Secretary was that the architecture should be innovative and that it would blend into the landscape of the region. Sayad stated that the design intent was to renew, "shock" the city (Miranda, 2008). "We wanted to cause a scandal in Brazilian architecture. In a good way" (Projeto&Design, 2009: 34). According to the Secretary, this work "will definitely put São Paulo on the map of major international architectural projects" (Projeto&Design, 2009: 34). The firm selected to design the project was Herzog & de Meuron.1

The Secretary states that the Swiss firm offered some features he deemed critical, including "their great interest in doing a project in Latin America, especially in Brazil, time availability, compared to other offices, in addition to the intention of investing in the country" (Projeto&Design, 2009: 35). The selection also considered that they were Pritzker award winners. In the Secretary's assessment, "Foster's, Peli's and Koolhaas' architecture makes their projects easily recognizable anywhere in the world, whilst Herzog & De Meuron's is always innovative, unusual" (Projeto&Design, 2009: 35).

The Brazilians Oscar Niemeyer and Paulo Mendes da Rocha, also Pritzker award winners, were dropped, according to the Secretary of Culture, João Sayad, because "they already had other projects in the city" (Projeto&Design, 2009: 35) and because they wanted to avoid a bid since it "would generate the possibility of changes to the project" (Miranda, 2008).

The decision provoked diverse opinions among the Brazilian architects. Some advocated in favor of the Swiss because of their architecture; however, the vast majority criticized the manner in which the selection was made. The Institute of Architects of Brazil (Instituto dos Arquitetos do Brasil - IAB) recommends opening public tenders (bids) for single public works.

Cesar Bergstrom, Urbanism director of the National Association of Architectural and of Consulting Engineering Companies (Sindicato Nacional das Empresas de Arquitetura e Engenharia Consultiva - Sinaenco), wrote a press release stating that the decision of then Mayor José Serra was "reversed xenophobia and a demerit for the Brazilian architecture" (Sinaenco, 2008). He reported that such a definition resulted from the completely erroneous interpretation of the Bidding Law (Lei de Licitações) 8.666/93, wherein the article claiming "bidding is unenforceable when the competition for the commissioning of technical services [... ] of singular nature, with professionals or companies of recognized expertise is infeasible" (Sinaenco, 2008) appears. In a competition that involves the construction of a cultural complex of approximately 19,000m2, three theaters and that will host two key state government cultural areas, with a total investment of R$ 300 million, "it is simply absurd to allege bidding unfeasibility and exclude the Brazilian offices of architecture", states Bergstrom (Sinaenco, 2008).

Continuing his reasoning in Bravo magazine (a significant national cultural magazine), Bergstrom advocates the commissioning of national architects, stating that "the problem would be best addressed by a national office, because the structure relates to the country's culture" (Orsolini, 2008) and adds, citing the lack of a Brazilian identity, "If we were talking about an administrative building, for example, the structure is almost universal, I would agree then that they would bring a significant contribution. In the case of a dance theatre, the building must have a Brazilian identity" (Orsolini, 2008). Meanwhile, the Brazilian architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha, responsible for projects such as the Brazilian Museum of Sculpture (Museu Brasileiro de Escultura - MuBE) criticized the reaction of Brazilian architects that opposed the decision of the Secretary of Culture as "corporatist and reductionist" (Orsolini, 2008). Noting what matters in the assessment of that impasse, for this study, demonstrates the lack of dialogue.

Another common criticism at the time regarded the work cost and the architects' fees. The state government estimated that the total cost of the construction project of the Dance Theatre of São Paulo would be 160 million US dollars. According to the Secretary of Culture, the contract signed with the office Herzog & De Meuron predicts the payment of a commission between 6.5% and 8.5% of that value, which means approximately between $ 10.4 million and $ 13.6 million. These values are much higher than those usually paid to national architects, whose fees, for works of such scale, are approximately 2% of the work value.

The Government of São Paulo defends itself from critiques by stating that the Swiss office selection is supported by Federal Law (Lei Federal) 8.666 of 1993, which determines that "bidding is unenforceable when the competition for the commissioning of technical services of singular nature, with professionals or companies of recognized expertise is infeasible" (Thuswohl, 2009). "Creating a few scandals is part of our job prescription" (Antunes, 2008: 27), states Sayad. "I have the impression I would find the same reaction in other professions. The hoopla and buzz are welcome, and expected. Let us hear the criticism from national architects. This is the most significant activity of national policy, to exchange ideas", he concluded (Antunes, 2008: 27).

Visibly, "creating a scandal" is the local Secretary of Culture's proposal for an area with serious social problems, including the lack of a comprehensive urban plan, which considers the problems associated with the housing sector, safety and the development of local trade. Clearly noticeable, the goal of designing an "iconic building" results from the effect of urban renewal strategies advocated by city marketing.

Therefore, as clearly noticeable by the local government, the goal of designing an "iconic building" results from the effect of urban renewal strategies advocated by city marketing.

Final considerations

A critical analysis of city marketing tools in comparison with the strategies used in the conception and design of the Cultural Complex-Dance Theatre results in the following considerations:

Speech is a city marketing tool. It is used as a manner of consolidating a political performance, including urban interventions, and gaining popular support. For speeches related to the cultural buildings of São Paulo center, there is a clear strategy of overshadowing the true urban and social conflicts of the region. This form of persuasion causes the population, influenced by the "cultural" speech, to believe that new cultural attractions suffice to renew the region. This unilateral speech is also used as propaganda to attract partnerships and gain local and even worldwide visibility. Therefore, we note that speeches were used as a form of city marketing to attract popular support and future investments.

Another aspect related to city marketing is the integration of architectural icons. These icons attract attention because of their scale, monumentality and unusual architecture and are used in many countries worldwide. The Cultural Complex-Dance Theatre of São Paulo combines all the elements listed to become an "icon" of local and international architecture. Its inclusion will change the urban landscape in the Luz area and all local spatial dynamics.

As in other city marketing operations, architects were selected from among the renowned names in the international media. The added value of the "brand" that signs the project is more significant than its spatial, functional or symbolic qualities. The architect's signature is, thus, used as a form of city marketing. According to Hazan (2003), contemporary icons gain further visibility because "they are designed by world-renowned architects, who with their professional recognition, help to mystify those works since their inception". Thus, only foreign, Pritzker award-winning architects were invited to the Cultural Complex Project.

Furthermore, demonstrates the local government's lack of interest in the impact of the Cultural Complex on its surroundings. There is full awareness that the new equipment will likely not reverse the state of abandonment and precariousness in the area. Although urban development projects belong to another administrative sector, a notorious lack of urban and social criteria guided the idealization of the project. Was the analysis of the area not considered? Is a "cultural" building a priority for the area? We should stress that the region already hosts cultural buildings, all of great relevance for the city, e.g.: Pinacoteca do Estado (museum), Estação Pinacoteca (museum), Sala São Paulo (largest concert hall in the state), Portuguese Language Museum (two of these works are signed by the architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha, the Pritzker award winner of 2006). This unique architectural complex, whose construction began in the 1990s, insignificantly changed the deplorable state of the Luz district (Medrano, 2010).

Another critical finding is the configuration, in the case studied, of the city-company-culture concept, combining money and power with art and culture. This strategy, according to authors such as Arantes (2007), does not bring benefits to cities and most residents. The urban development plan for the surrounding areas of the Dance Complex, named Nova Luz (New Luz), was commissioned by two major private corporations, the construction company Odebrecht and the corporate group headed by the incorporator Company S.A. Both the control of the urban plan for the area and dialogue with local players involved (residents, traders, etc.) did not exist. This type of "strategic operation", in which public goods serve the private interests, has occurred in recent decades in many parts of the world - and was challenged by several authors (Borja, 2001; Harvey and Smith, 2005). Its belated action in a country with serious social problems like Brazil accentuates the misconceptions of their ideological, economic and urban matrices.

Image 7: Street in Luz district. Precarious urbanization and social problems near iconic buildings. Photo: Eduardo Costa and André Kobashi 2011.

The inclusion of the Cultural Complex-Dance Theatre of São Paulo has a strong city marketing appeal, which transforms it into a high-impact urban project. The manner whereby it is being introduced, without a single study between the building and surrounding areas, will not generate benefits for the neighborhood and resident population. Regardless of the partnerships established to enable the process, it should be the government's obligation to control the urban plan in the area and its meeting of local needs. Iconic buildings, when required, should be accompanied by careful design and urban planning, addressing the different players involved. In this particular case, a thorough analysis of the local social and urban reality is essential. Without this analysis, the intervention will only generate occasional benefits, the opposite of what could be an extensive project, whereby the people of the Luz area could benefit from an urban structure consistent with the historical relevance of the neighborhood and the quality of the cultural buildings installed.