Dwellers display original solutions to appropriate architectural fabric and build a new sensory space: greenery colonizing abandoned corners, protecting those from noise and sun; paints and artistic installations to distinguish their quarter, collective actions to appropriate unused places.

Developed within the context of public space studies (Whyte, 1980; Gehl, 1971; Jacobs, 1961; Lynch, 1975; Cullen, 1981), the proposition aims at understanding if using the concept of ambiance informs about urban micro-space from a different perspective compared to other urban disciplinary methods; connecting elements that are not usually related because they are studied by separated disciplines: social disciplines or spatial disciplines. Ambiance is here understood as the emerging feature of the relationship between inhabitants' spatial practices, space and its sensory elements, since built environment becomes meaningful when used, inhabited and enhanced by individuals. The study of the environment -in the sense of ambiance- would focus therefore on understanding the spatial and sensory devices that allow social practices to produce a particular and identifiable characteristic of a given space. Introducing the concept of ambiance into urban discipline allows getting around the problem of comparing spaces that are different in form and scale, as it focuses on the relation between constructed/sensory space and social use.

If space shapes inhabitants' practices, in return, the inhabitants' practices of space create uniqueness: this customized space is considered to have an ambiance. The space possibilities offered to inhabitants are anchored in built form which is at the same time defined by norm, public policies, urban approaches, and the evolution of disciplinary theory and practices. However, time after time, inhabitants transform space and re-signify it with their own proposals (De Certeau, 1990). Public space is the privileged field of study for this relation. It is the result of government's urban actions. In this perspective, urban renewal, understood as a principle of reinvestment of consolidated sectors in the city, is an object of study that facilitates tracing the origins and implementation of public space as defined by political-ideological and disciplinary principles.

Considering space in a sensory, constructed, and social perspective, this paper reports the study of three different areas of the inner district of Santiago, that have been renewed by public policies in three different periods, assuming that precedent decisions shaped the city at that time, and also determine its use today. The results presented endorse in a larger research that, using ambiance as a lens, pretends to understand why some renewed sectors are better preserved than others (Arizaga, 2016).

The focus is on public-space ambiance and the possibility to understand through it, the urban realm, as, expressed in the relations inhabitants signify: in the use of constructed space, under sensory circumstances.

The central concept ambiance is a French term used also in specialized English literature about public spaces by authors like Gordon Cullen (1968) or Sydney Brower (2000 [1966]) yet not specifically defined by them, however close to other terms as 'character' used by Lynch (1991 [1965]) and Bacon (1974 [1969]). In 1979, J.F. Augoyard wrote his seminal book, Pas a Pas, essai sur le cheminement quotidien en milieu urbain later translated as Step by Step: Everyday Walks in a French Urban Housing Project (2007), and introduced ambiance into French urban studies.

Augoyard contextualizes the concept of ambiance:

Urban atmospheres are born in the crisscrossing of multiple sensations. In this immediate experience of the world, the rain, the wind and the night hardly have any value of their own. What the inhabitant retains therefrom is the raininess, the windiness, the "fearfulness", that is to say, the affective tonality. Thus, raininess (coldness, dampness, desire for shelter) will qualify the lived world in that very moment. An everyday ambiance takes consistency on the basis of a focusing, of a value of one element in the environment that will symbolize and replicate in an expressive way the atmosphere in which one is bathed [baigné]. (Augoyard, 2010, p. 120).

Ambiance, in this sense, would be an important element for understanding the totality of an everyday place or that of an exceptional place: the element that the inhabitant highlights will be the one that synthesizes dispersed qualities of the built and sensory environment when it is perceived and used.

As a public space cannot be apprehended under a logic covering only built or social dimensions, it is postulated that use is what ensures the sustainability of the built space, and, also the first symptom of the relationship between physical and sensory built space and inhabitants. Likewise, as there are places and uses that have a sustained positive development over time -are used all day long, are used for a long time by inhabitants or have existed for many years - the approach aims to understand the essential characteristics of those spaces.

The idea of using the concept of ambiance restores the function of built space in perception, valuing the role of space in the construction of perception and social ties (Augoyard, 2004). As Thibaud proposes, eth-nomethodology substitutes the study of perception per se by the study of the implementation of perception in practice; aiming to understand how individuals' coexisting ways of perception are incorporated in daily activities and are their constitutive elements. As he states, such an undertaking engages thereby "a praxeological approach to perception" (Thibaud, 2002, p. 25).

What is proposed here is the cross-section of an observation: the urban space exists when individuals use it. In this regard, there is a necessary reciprocity between the individual and the space he/she inhabits, there is an existing co-determination between the built space and the uses the inhabitant makes of the architecture (Augoyard, 2010; Thibaud & Grosjean, 2010). Therefore, what is sought to study is how the built and sensory space shapes use, and vice versa, how uses and practices re-define, shape and re-appropriate space. Consequently, the study will be centered in practices of small urban spaces (using Whyte's term, 1980).

The objective is to show how a situation integrates and articulates different elements (built and sensory) that shape and are shaped by inhabitants to produce uniqueness. Included as such, ambiance is presumed to explain the staging of everyday life, as a social and cultural practice that structures the underlying, yet unnoticed, values that express the coherence of a place and is crucial in understanding the way inhabitants and visitors appreciate a district in particular and a city in general.

Methodologically, the downtown district of Santiago was submitted to a socioeconomic analysis, choosing districts with homogeneous outcomes with university-graduate householders, relative smaller family units, similar numbers of rooms per dwelling and so on. The manifestation of this socio-economic homogeneity has different expressions in the three chosen neighborhood's public space, because even though class sensibilities mold urban milieu, it is shown that this expression is also conditioned by the relations between built space and the potential uses and practices it enables. The specified areas have similar urban amenities: accessibility by underground, green areas and functional services, which allow a comparison between sectors.

Those areas of study are at the same time representative of the three periods proposed for understanding urban renewal policies in Santiago and described in extension in a previous characterization of urban renewal in Chile (Arizaga, 2019), briefly described below. In this case, the present proposal aims to expose the relation between historical decisions and their influence in actual uses.

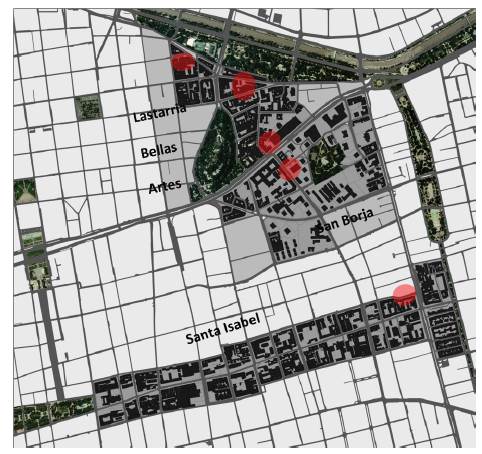

First, the three neighborhoods and the renewal policies are described. Then, the results of repetitive itineraries and the chosen places where the sustained use of space was particularly interesting, are illustrated. It enabled to define selected places where the observation of sensory conditions and the way inhabitants respond to them is studied on a broader level (Figure 1).

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 1 Lastarria-Bellas Artes, San Borja and Santa Isabel and focus (red) in selected spaces.

Focusing interest on the inhabitants' practices of the constructed and sensory space, three particular practices were selected: waiting, selling and exposing, as representative and comparable in the three neighborhoods. This practices and the supports used for them informs, first, on the way people's attitudes are molded by constructed and sensory space, and second, on how inhabitants' attitudes shape the city.

Three Neighborhoods, Three Urban Renewal Public Policies

The city of Santiago evolved in the 20th century from its colonial form to today's global city. In this process, the inner city's population has decreased: from representing 75% of the population of the province at the beginning of the century, it now, at the beginning of the 21th century, constitutes 4.5% of it, and this, in a context of exponential growth on a national and regional level. This growth and subsequent contraction, assuming a cycle well known in urban studies, explains the deterioration and need for public policies of urban renewal.

Urban renewal policy, in the context of this article, is understood as a legal, political and urban proposition with clear intentions to change center-periphery imbalances and re-qualify the consolidated city frame. Considering those indications, three different periods for urban renewal policies are assumed in the context of this article; covering more than a century of Santiago's urban history, reflecting three political and economic terms, as well as three different stages of urban discipline and the way the Chilean State has intervened the capital city.

The first evidence of urban renewal policy is the Plan de Transformación de Santiago (1872), defined by its intendant Vicuña Mackenna, and that takes place in a context of a national urbanization process.

As diseases and overpopulation increased, the plan was hallmarked by public health concerns and the desire of modernity. The Vicuña Mackenna Plan was the first initiative designed to re-invest the inner city with a clear intention to retain, control and improve it and, at the same time, to differentiate it from the outside: distinguishing the 'proper city' inhabited by the fledgling bourgeoisie from the 'improper city' which was confusing and inhabited by the poor, the workers and the outcasts (Vicuña Mackenna, 1872).

This plan is marked by urban design in applying the policies: State investments converge in public spaces and monumental edifices as a manner to promote private placements. Part of the projects proposed by Vicuña Mackenna concluded in 1910 during the first centenary of the Chilean republic: a sewage system (1906), the circumvallation road (Camino de Cintura) and the Parque Forestal (1910) and its museums located on the edge of Barrio Lastarria-Bellas Artes analyzed below, as many others. Later on, as Vicuña Mackenna's urban-renewal policy model was developed, an urban norm designed by K. Brunner (1932), was adopted in 1939 allowing a harmonious development of the built environment. Those two dates and their related plans marked the first urban renewal policy: from Vicuña Mackena's plan expressed in the Ansart's planimetry of 1875 to the normative plan of Brunner promulgated in 1939.

After this first urban renewal period, expansion issues absorbed the city of Santiago and its planners. Even if they kept a constant concern about the inner city to maintain an overall balance; the downtown area was partially abandoned. Nearly a century later, the first policy with clear intentions of urban renewal is formulated. Labeled welfare state and deeply inspired by the CIAM, this policy will produce renewal projects bringing about a radical change of the existing urban frame.

In a context of sustained prosperity due to booming periods supported by nitrate mining (1880-1930) and later copper mining (1920-1971), the state undertook social, educational and housing policies. During Eduardo Frei Montalva's government (1964-1970), a Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (1965) was created as well as the CORMU, Urban Improvement Corporation which, from its starting date in 1965 to its dismantlement in 1976, marks the second period. The function of this institution was to: "Improve and renovate blighted areas of cities through redevelopment programs, rehabilitation, maintenance and urban development" (CORMU, 1969). It was deeply housing-oriented but dissociated the housing problem from the urban one, as two related though non-identical issues. In a reformative perspective, this policy had clear intentions to rebalance urban populations and urban access to amenities for everyone.

In a period of massive growth of Latin-American cities (Romero, 2010 [1976]), the downtown district had already lost its upper-class population, which was attracted by the garden city and started to settle at the foothills of the Andes Mountains range. This urban restructuring proposal was not only spatial and economy-oriented but was also attempting a social transformation. The Remodelación San Borja project, analyzed below, is the draft manifesto of this policy that sought a radical transformation of urban space for the new man: "if the redemption of society and the advent of the new man were to be announced, then architecture was needed to assist in this spiritual mission, announcing the new time, taking charge of the visionary aspect of the undertaking" (Raposo et al., 2005, p. 235).

Then, after the military coup (September 11, 1973), the State reduced its participation in the economy to play a merely subsidiary role and abstained from participating in the generation of city space, even if throughout this period, punctual improvements were made.

Downtown Santiago sank into progressive deterioration: obsolescence of constructions, traffic congestion, car repair shops and small industries being installed in the once upscale districts of the early 20th century. However, this was accompanied by the emergence of office towers in the main axis of the city, a phenomenon associated with the opening of the first subway line. In the 1980s, the downtown council began to concern itself with a social problem that escalated into an economic issue for the central district in terms of governance and public service funding. The 1985 earthquake marks the beginning of the third and still current period: authorities stimulated by its negative consequences become aware of the problem and created the CORDESAN, Downtown-Santiago District Development Corporation. Before the end of the military government (1973-1990), a law was enacted in 1987 to designate areas of urban renewal, and in 1991 a government subsidy was established to enable citizens to purchase flats in those defined areas.

Based on different studies, the policy is sustained by this housing subsidy and the Development Plan for the Renewal of Santiago with a demonstrative example in Santa Isabel quarter. The Plan aims at "social heterogeneity through property development and real estate promotion, fostering urban renewal as well as urban regeneration, the reusability of urban heritage and densification" (1991, p. 27). Nevertheless, deeply influenced by the obsolescence paradigm as a mode of production, the modest city heritage will be destroyed and replaced by dense constructions that operate without an integral logic. This time, space is the forgotten variable. In this new urban renewal policy, zoning and the standardized norm will be the only guarantees for inner-city renewal; the urban design as a guiding principle and as a mode of production is then completely abandoned; public space disappears from the city's urban renewal policies.

The three urban renewal policies described, express differently in urban morphology: conserving the former morphology of the quartier in the plan of Vicuña Mackena; proposing a new urban structure in the CORMU's period and densifying the traditional frame in the third period. Those different spatial conceptions have consequences in the porosity, permeability and the possibilities of circulation of urban space that can be resumed in the three studied neighborhoods. Furthermore, those urban renewal policies materialized in projects that are experienced differently by citizens nowadays, understanding those differences is the purpose of the second part of the article.

Three Neighborhoods, Three Constructed and Sensory Spaces

An extended field work was done to understand the places and devices that resume the differences between the three neighborhoods. In the selected places three practices: waiting, selling and exposing were particularly observed -as common practices of all the sectors - to study these differences. In that sense, analysis of practices is the focus of the methodology, assuming that by their acts and modifications of the public and constructed space, inhabitants reveal their preferences (Bourdieu, 2007); and, doing so, the spatial and sensorial qualities of the urban fabric.

The subway station, existing in the three sectors, was considered a privileged place of observation to compare uses and practices of space. In this place, the actions of people such as waiting, selling, showing, exhibiting and passing, express from a praxeological perspective, their adherence and assessment of the built environment. The immediate surroundings of this access to the neighborhoods, were confirmed as the place where the essence of the quartier is concentrated. In these places the permeability of the urban fabric, the characteristics of the sidewalks, the immediate shops and the attitude of pedestrians were studied, as well as the existence of pleasant or unpleasant noises. In particular, considering senses, body expressions, different uses of urban devices, supports and materials employed, the existence of elements that challenge sight and smell as colors and food-cooking in the street, were registered. Likewise, the interpellation of touch through objects that can be bought and therefore touched, as well as the possibility of experimenting through sight, as Pallasmaa (2010) points out, the roughness, patina and softness of the construction materials were determining factors in the observation.

Lastly, the expression of the passage of time, as what allows people to imprint their stamp on the urban space (Lynch, 1975; Bentley, 1985) and manifest the subtle individual or collective transformations that the inhabitants make to the original architectural project, through vegetation, graffiti or other elements, were recorded with interest as they are the testimony of appropriations of constructed space.

The three quarters are briefly described below to focus on the findings of the observation work. The pictures are essential as a support for the analysis in order to understand how, through the different uses and practices of the public space, the inhabitants express the characteristics of the neighborhoods, generating a unique combination of space, uses and expression of their inhabiting: an ambiance.

Lastarria Bellas Artes, the 'Trendy' Neighborhood

Before Vicuña Mackenna's Plan, Lastarria-Bellas Artes was a colonial neighborhood, carved by the division of the Mapocho river into two branches and a system of water canals resulting from its strategic position in the city. The canalization of the river and the subsequent control of its floods induced the transformation of the colonial sector into an upscale district bordered by the Parque Forestal, included in the plan. Despite this metamorphosis, the urban blocks maintained the intricacy of the original frame, which, combined with a significant complex of noble buildings, embodies this neighborhood's core structure, remaining until today.

This district is permanently renewed by private operations anchored in public projects (the underground, the GAM museum, for example). The form adopted by new investments is "urban acupuncture" (Sola Morales, 2008): preserving valuable edifices in new real estate operations, and marketing them based on public space qualities.

This particular frame enables the existence of a multitude of cafés, restaurants, art galleries and Chilean handmade design-object's shops, that coexist with traditional commerce, attracting visitors from the whole metropolis.

In the Bellas Artes underground station, waiting can be an opportunity to enjoy the evening with an ice cream, to rest on a bench, to listen to street music.

Waiting is something to be done alone or simultaneously with other people who are also waiting: each person in his/her own space in a relaxed posture as a result of each one's confidence in the other. Coffees and bars create particular devices that license people to see without being seen.

Streets' merchandises in Lastarria-Bellas Artes are sophisticated: jewelry, handmade accessories, decorative items and artistic expressions, coexisting with the sale of vegetarian sandwiches. This is combined with the traditional sale of flowers and plants, or the formalized disposal of antiques and second-hand books in the Lastarria-Merced street corner. Also, the offer can involve the selling of 'experiences' on the street: miniature theater shows, jazz and makeshift exhibitions. Those transactions are made on the sidewalk, momentarily transformed in a kind of 'beach', with vendors comfortably leaning back, or with sophisticated carts being progressively installed and complemented by racks and other display elements (Figure 2). Furthermore, the sale may overflow from the inside out, when licensed stands are installed in residential buildings or when indoors sales are promoted in the street. Then, buying represents the possibility to get into interiors: flats are converted into improvised tattoo parlors or boutiques and passers-by can visit the insides without invitation. Thus, the neighborhood's indoor and outdoor are mixed up in a peculiar and 'promiscuous' way.

In this same area, inhabitants convey their concerns in an artistic and refined manner. Subtle-minded and delicate-spirited residents articulate their reflections on space as belonging to a so- called 'hipster', 'bohemian' or 'fashionable' neighborhood, leaving a hallmark that enhances its classiness. Elaborated posters with subtle messages, simulating sophisticated personalities subverted by local messages or details (see the Tibetan monk with a Louis Vuitton foulard Figure 3) create a visual trail worked out by the photographer Claudio Caiozzi. A little further ahead, another emerging artist uses a different support as a vehicle to transmit his/her message: construction walls covered with clothes to which he/she adds sophisticated arrangements (Figure 4). The messages reflect an acute observer and are directed to a particular audience.

These visuals are complemented by street performers who offer sophisticated shows: bands playing musical instruments brought from Asia; Flamenco performances with improvised tablaos and jazz groups. Last but not least, the ecological manifesto finds a wide means of expression in the collection of recycled materials with 'directions for use', as well as in organic markets and advertising of organic products.

Body kinetics are puzzled by the multiple possibilities and peculiarities created by this space and its interaction with inhabitants; all this in an atmosphere rarely uninterrupted by cars and their disturbing noise. The neighborhood, with its visual and musical ambiance, attracts flâneurs, especially on weekends. At the same time, surrounding restaurants and sophisticated products stimulate smell and taste; and the sense of touch is mediated by clothes arrangements and the offer of handmade products.

San Borja, the Modern Neighborhood

This modern project introduced in 1969 and finished in 1976, with the towers and the park in the center, occupies principally the lot of the ancient San Borja hospital. Today, the population, as well as the infrastructure, has grown old. There are maintenance problems and renovation works are scarce or have only recently started. The current district's challenge is to be reincorporated into the city's demands.

The original plan of high buildings ensemble was built upon a commercial platform, a feature common to Modern Movement projects, and intended to allow upper-level circulation based on footbridges, currently shut down. The scheme of a free space, with multiple access possibilities, did not fit with local desires: the projected flow is now interrupted by grids and garden trellises. Nevertheless, the patina of buildings combined with buildings from the 1940s in the surroundings now creates a peculiar ensemble.

People in this neighborhood show similar practices, mainly waiting around the underground station: a semi-buried square structure that was supposed to connect the entire neighborhood with the footbridges. Here, in a rather deteriorated space, people wait sitting on benches surrounding a central green area, or resting on a poorly functional wall. The friendliness of space, in this case, is not consistent with the large number of people hanging out around. Waiting is certainly a compelling need that can be realized in a deteriorated milieu. But it is also true that this space offers many options: sunlight, shade, total exposure or semi-covered spaces. And, even if chaotic, vegetation provides a pleasant sight (Figure 5).

The underground station also offers a space for selling, given the massive flow of commuters. A large variety of goods are sold, and sporadic activities -such as leaflets distribution or commercial promotions- also take place. Informal trade is practiced on the floor, preferably in front of the underground access stairs. Wares offered vary according to the time of the year: scarves, jewelry and accessories, sweet bakery, sandwiches, churros, for example. Nonetheless, during the Christmas period, a craft market offering handmade items, accessories and plants is installed under the footbridges, giving these structures a new purpose.

Informal trade also takes place at Avenida Portugal, where manufactured products are offered according to seasonal availability and needs: socks, tights, jewelry, sunglasses, etc., that can be combined with some handmade items such as 'dream catchers' or handcrafted jewelry. This trade activity arises on the sidewalks, confining pedestrian traffic to a narrow corridor between the blankets on which vendors display their wares. Thus, pedestrian circulation is conditioned by space, and passers-by have to tread with caution at a regular speed, paying attention to their immediate surroundings (a crouching buyer may cause an accident). So, walking through this avenue would hardly be a pleasant experience, yet people simply pass by, and this largely explains why the ambiance associated with the vitality (using Jacob's term, 1961) of this public space is indifferent.

As far as business is concerned, a particularly interesting one takes place in San Borja ensemble: it is called La Feria Chica, a licensed fruit and vegetable stall where a group of dwellers is usually hanging out and exchanging some words with the friendly stand owner. It involves bright colors and fruit scents. A place where traditional commerce meets modern architecture's project and the hectic pace of contemporary city life: a corner of paradise barely protected from vehicles' noise and the summer's sunlight (Figure 6).

Continuing with chosen practices, in San Borja, signs and flyers are commonly posted on poles and walls, where not only professional services (plumbers, house painters, teachers, etc.) but also festivals, exhibitions and neighborhood's activities are advertised. Footbridges' pillars are in this context emblematic spots of the Remodelación San Borja: an example of an alternative use of a massively available resource. Another common display medium is the hairdress-ing salon's signboard where out-of-sight local stores are advertised, thus modifying the itinerary of passers-by: resorting with clever solutions to remedy the shortcomings of a space that is not allowing a fluid access to trade.

In San Borja, massive and collective events are of common occurrence. Particularly, there are recurrent activities on the footbridges collectively promoted by occupying space through civic demonstrations: music, collective planting, and film festivals (2014-2015). During concerts, food-trucks and other carts take place over the commercial platform making it a living space with color, sounds and smells of coffee and crêpes. It is the opportunity to sell 'homemade' items, listen to emerging musicians, talk and enjoy the evening. The gateways then become a place where students and teachers from university nearby, inhabitants of the towers and other visitors meet.

In general, San Borja inhabitants express themselves collectively in large open spaces, walkways, walls and other available supports, as can be seen in the multiple fenced gardens cared for by neighbors, replacing neutral space of modern architecture with places they can nurse together. Here the inhabitant re-appropriates the existing city resources in order to call the visitors' visual attention. Together, in a concerted or fortuitous way, inhabitants create a special way of experiencing the neighborhood and a fresh re-interpretation of the Modern Movement project.

It is like the unitary project of San Borja needed a common action of its neighbors for its reinterpretation, whereas individual interventions support a unitary result in the organic area of Lastarria.

Santa Isabel, the Real Estate Neighborhood

Santa Isabel Street was gradually opened between 1980 and 1990 by combining several small streets and blind alleys that had been existing since the early 20th century. Once constructed, the street became one of the important axes connecting eastern and western Santiago, with a heavy daily vehicular traffic that avoids a pleasant use of sidewalks.

Regarding the old middle-class neighborhood of the 1960s, only ruins and debris of houses and workshops remain awaiting imminent demolition, even though some of them are still inhabited. Up to 23-story high-rise buildings replaced the ancient urban fabric of single-story houses, thus producing a break with traditional scale and establishing a new relationship with the pedestrian space, which is condemned to remain in the shade of the buildings. Some of the smaller constructions, which have been overlooked by the real-estate boom, are soon to be turned into new buildings, or are still providing shelter to mom and pop shops, cycle repair tents, and in the worst case, in an area transformed in showrooms promoting new apartment buildings ( ).

Accessing this neighborhood by subway, a mixed commercial-residential zone can be found. Shops, institutional services and other businesses are less visually appealing than in the other studied sectors. As in the other two stations, in this one, people also wait, sitting on the benches along the access to the station, leaning on the handrail or simply standing outside. Waiting is not as pleasant as in Bellas Artes station, and there is not such a wide range of possibilities as in the access to San Borja station. Commuters seem to have gotten used to their fate, and pass by rushing to their destination. Only in the evenings, after working hours, the place seems to liven up: students, women getting out of work and street vendors inject some vitality into the atmosphere. The hustle and bustle at the nearby coffee shop begins at peak hours and is prolonged until midnight. So, at these hours, as in the other cases, the station offers a trade opportunity. Informal vendors settle beneath the semi-buried section of the station or sit on the planters' low borders: wares such as bread, clothing, jewelry or other manufactured seasonal products are offered on the floor. This trading environment is less sophisticated than in Lastarria-Bellas Artes and less institutionalized than in San Borja. There is a sort of tacit division of space, where each vendor occupies a strip on each side of the stairs, leaving just enough space for commuters' circulation. Besides this, a more spontaneous and marginal trade takes place along the street: 'sopaipillas' [fritters]; tacos and others, are offered in cooking-carts that attract workers on their way home.

Exceptions to those humdrum days are San Camilo Street market days. On Wednesdays and Fridays, this street, perpendicular to Santa Isabel, is transformed into a colorful setting filled with scents. The traditional fair's tails [colas de la feria] of the market allows vendors who do not have a licensed stand, to engage an informal and marginal trading, offering second-hand clothes, low-priced cigarettes, anticuchos [barbecue], juice, cooking utensils or sweet bakery. This gives the place a much more typical flea-market atmosphere. But as soon as the street market leaves, this colorful ambiance also vanishes.

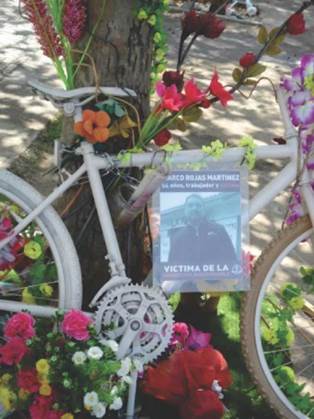

Regarding street use, business announcements are also much more modest in Santa Isabel: hand-written cardboards attached to trees, or leaflets offering room-and-board lodging. Likewise, public space serves as support for ideological graffiti expressing disapproval or social criticism, for example "Keep watching TV, but don't complain afterward", "All copper to Chile and Chilean workers...", or expressions of regret through installations alluding to recurrent road accidents involving cyclists (Figure 8). Here, as in the other sectors, inhabitants display their artistic talent on different media, which shows the existence of different degrees of sophistication in all three neighborhoods, depending on the precariousness of the format and medium used.

Confronted with those three spatial practices: waiting, selling and exposing, the Santa Isabel neighborhood shows its own reality. Scarce and shadowy space for pedestrians hinders the emergence of attractive ambiances, except on market days, when the neighborhood shows what seemed to be its ancient socialization practices, with people greeting each other in an informal but usual context. Nevertheless, residents make their presence felt on walls and express their opinions, giving color and life to nearly always empty streets. Public spaces provided by real estate investors: standardized and equipped with workout machines, gardens and children's playgrounds, are rarely used. Commuters just go from the subway station to a private condominium with its own swimming pool, gym and children's playground.

Here, massive individual projects give no place to collective actions. Inhabitants are confined in their own individuality as the collective space has become only a functional place.

Conclusions

All three neighborhoods considered in the research not only show the evolution of urban renewal policies in central Santiago but also the challenges of densifi-cation in a city that, as many others, has consumed entirely its valley.

All three periods analyzed and illustrated show a progressive neglect of public space in Urban Renewal's policies: starting with a detailed urban design, policy is ultimately confined to a norm and real estate operations. The original frame of the city, its combination of scales, time and styles, as well as its capacity to receive different people has been neutralized.

Nevertheless, inhabitants are reclaiming their city through small-scale uses combined with their particular and peculiar practices that give birth to attractive ambiances. Flexible spatial conditions make it possible for inhabitants to implant informal uses in the constructed frame. Dwellers display original solutions to appropriate architectural fabric and build a new sensory space: greenery colonizing abandoned corners, protecting those from noise and sun; paints and artistic installations to distinguish their quarter, collective actions to appropriate unused places.

The ambiances ensure differentiation between these quarters, revealing the binding of the constructed space and the sensible environment in the practices they enable. Considering the comparable middle-class characteristics of the chosen neighborhoods, ambiance also expresses distinctions in inhabitants' daily habits.

In Lastarria-Bellas Artes, the potential offered by space allows to magnify the incipient ambiance and transform it into a strong and unique one. An intricate urban frame, different styles, different temporalities of buildings, but also a bench or a wall, will allow the expression of inhabitants' art, denunciation or exhibition. Ambiance can exist here thanks to a combination of urban space and sensory conditions to be interpreted by inhabitants. This is the result of an urban policy centered in urban design which constructed a solid and porous frame that is at the same time consolidated and opened to acupunctural changes, (using Sola Morales term, 2008). This possibility of reinventing the units conserving the essence of the neighborhood ensures the coherence of uses and their permanency over time, all day and the weeklong. In Lastarria-Bellas Artes, individual actions converge to unity, as if the coherence of the urban fabric fostered harmonious actions.

In San Borja, space is arid, but residents domesticate the Modern Movement project in a version more akin to their needs. The dweller in this case will occupy the interstice where modern architecture joins the preceding city: colonial walls, plane trees and especially a traditional fruits and vegetables stand with a distinctive dynamic. Inhabitants will appropriate any piece of land to set up their garden. Collectively, in a friendly and modest manner, the city will re-signify the pure space of modernism clinging to its own weapons: the footbridges. Here the unitary architectural project is certainly less permeable to changes, but nevertheless seems to accept minor interventions and aggregates, offering still plenty of possibilities for new interpretation and re-appropriation. The accumulation of little dissimilarities over time, installs the diversity in the homogeneous project.

The Santa Isabel's case, with pedestrians quickly passing by unwelcoming buildings, shows less coherence between built form and people's needs. The city crumbling and abandoned only reinforces the reasons for demolition. Nostalgia still clings to the more modest everyday business: grocery stores, cycle repair shops. Playgrounds and workout machines, installed by the real estate companies, challenge few users. The fast traffic flow and closed façades offer dwellers little living space. Only in those few spots, where the ancient city emerges as a small-sized building, city life takes over. There, traditional activities and an intermediate scale create the possibilities in which ambiance could be anchored. The street market, though ephemeral, is the highest expression of the neighborhood's potentialities.

In this neighborhood, the sum of individual architectural projects resulted more homogenizing than the modern movement project, avoiding by this lack of diversity the emergence of ambiances and consequently the differentiation of this quarter.

In these three once renovated spaces, the study of practices enlightened the understanding of devices that enable the emergence of ambiances. Inhabitants invest space differently in each case, either completely appropriating the street and the urban fabric, or choosing exceptional locations in an unproductive space. Through their individual or collective actions, residents create and sublimate the city and thus take part in its formal possibilities to produce singularity. Even in an homogenous quarter as Santa Isabel, inhabitants express their ability to capture the possibilities of architectural elements, urban frame, and sensory elements. With their contributions to public space, they show the importance of distinction, the challenge of urban policies to leave space for the expression of the inhabitant: making it more flexible and multiplying the possibilities of occupation and appropriation of public space to allow ephemeral uses and diverse practices that enrich and vitalize the city. This way inhabitants express their understanding of urban milieu and their preferences for values and distinctive-ness of constructed solutions. The potential each sector has for interventions affects the ambiance of each neighborhood, highlighting this way the non-neutrality of the constructed space and the need for an 'urban-minded' norm and policy, to quote José Luis Sert (quoted in Krieger, 2009).