Cinchona is a genus of plants of high medicinal value, such as Cinchona officinalis, C. pubescens, C. calisaya, whose bark contains quinine, which was supplied as the only treatment against malaria for more than three centuries (Cóndor et al., 2009). The species of this genus were overexploited and their bark was traded in several countries. According to a conservative estimate, between the 17th and 18th centuries about 500,000 kg of bark was exported annually to Europe (Van Der Hoogte and Pieters, 2016).

The natural ecosystems of C. pubescens have suffered severe damage due to migratory agriculture, cattle ranching and logging (Arbizu et al., 2021; Huamán et al., 2019), making it difficult to find populations of this species in the forests of Peru (Buddenhagen et al., 2004), which has led to prioritizing the conservation and recovery of this species in Peru (Albán-Castillo et al., 2020). Agroforestry is an alternative for the recovery of native trees, one of the complex stages lies in the production of seedlings at the nursery level (Abanto-Rodriguez et al., 2016); especially in the seed germination phase, since it depends largely on quality factors such as type of medium, substrate, humidity, fertilization and botanical seed (Santos et al., 2010).

Cinchona pubescens is mainly propagated by seed, which is of great importance in the agroforestry management of the species (Vásquez et al., 2018). Under natural conditions, C. pubescens has a low germination and regeneration rate (Armijos-González and Pérez-Ruiz, 2016; Espinosa and Ríos, 2014), finding them only in remote sites and in small groups (Buddenhagen et al., 2004).

The substrate must allow good oxygenation, nutritional balance, and good water retention, in addition, it must provide a pH compatible with the species, adequate electrical conductivity, and be free of chemical elements at toxic levels (Abanto-Rodriguez et al., 2016). To meet the maximum of these required conditions, substrates must eventually be used in combination with each other or their natural form (Frade et al., 2011). Therefore, the objective of the study was to evaluate the effect of forest soil and sand on the germination of C. pubescens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

The trial was conducted from November 5, 2020 to January 6, 2021 in the community of La Cascarilla (5°40'16.5"S and 78°53'11.6"W), province of Jaen in Peru, at 1810 masl. Annual precipitation is 1730 mm, minimum temperature of 13.0 °C and a maximum of 20.5 °C (Fernandez et al., 2021).

Collection and drying of biological material

Seeds of C. pubescens were collected in October 2020 from a single existing population at the locality of La Cascarilla (5° 4037.96S and 78° 5327.0W) at an altitude of 1760 m 1 kg of mature capsules (brown to brown color) were collected and packed in cloth bags for transfer to the nursery. The fruits were subjected to a drying process in a low light environment for 15 days, after dehiscence, seeds were selected in optimal phytosanitary conditions, with uniform size and purity; they were then stored in cloth bags at room temperature.

Trial set-up

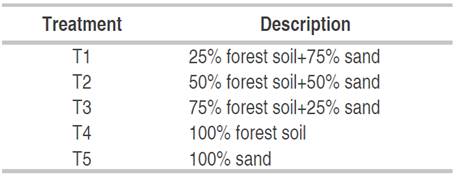

A sub-irrigation chamber of 1 m long, 0.45 m wide, and 0.5 m high was divided into 15 experimental units of 0.15 m wide, 0.2 m long and 0.1 m high. In each replicate, the combined substrates were placed according to the standardized ratio (Table 1); then they were moistened to field capacity and 100 seeds of C. pubescens were sown per replicate, after which daily irrigation was applied (0.10 L m-2) to ensure that the moisture content remained constant throughout the trial process.

Experimental design

The experiment was conducted under a completely randomized design with five treatments (Table 1) and three replicates per treatment; 100 seeds of C. pubescens per replicate and 1500 seeds were used throughout the trial.

Evaluation and data recording was carried out daily for 60 days, and the presence of the root apex was considered an indicator of germination.

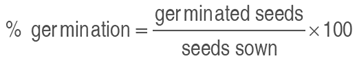

The germination rate was determined according to the following equation:

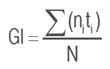

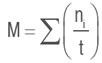

Additionally, parameters related to seed germination were calculated according to González and Orozco (1996):

Germination Index (GI)

Average germination time (T).

Germination speed (M)

Where:

ni: number of seeds germinated each day i

ti: number of days after planting

t: time from sowing to emergence of the last seed

N: total seeds sown in the study

The assumptions of normality (Shapiro-Wilk) and homogeneity of variances (Levine test) were verified. Then, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for each response variable and mean values were compared using Tukey's HSD post hoc test (P<0.05). Data were processed in StatGraphics Centurion XVI software (StatPoint Technologies Inc, Warrenton, VA, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

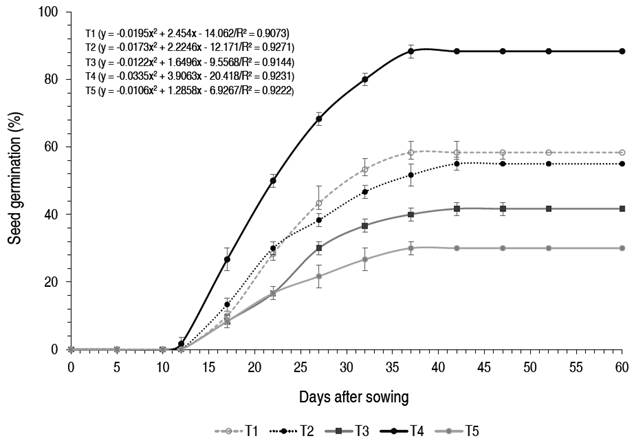

Seeds of C. pubescens germinated 12 days after sowing. Thereafter, germination increased daily, reaching the highest cumulative germination rate at 42 days (Figure 1). The cumulative germination curves show a quadratic polynomial trend, with a coefficient of determination close to 1 and with a certain degree of similarity in all treatments. The highest germination occurred between days 17 and 27 in all treatments and then its increase was minimal between days 28 and 37; completing the germination phase at 38 days (constant). However, the cumulative germination curve of T4 was always higher than that of the other treatments and T5 remained constant and below the mean.

The germination process of C. pubescens seeds started on day 12 and concluded on day 42, when the highest cumulative germination rate was recorded; these results differ from those reported by Caraguay et al.(2016), who indicated that C. officinalis seeds began to germinate on day five and finished at 35 days; these differences may be related to genetic, physiological (phenol content) and morphological conditions of the seeds (Herrera et al., 2006; Armijos-González and Pérez-Ruiz, 2016), in addition to other factors such as humidity, soil, nutrients and agricultural management (Bonfil-Sanders et al., 2008; Meza et al., 2004).

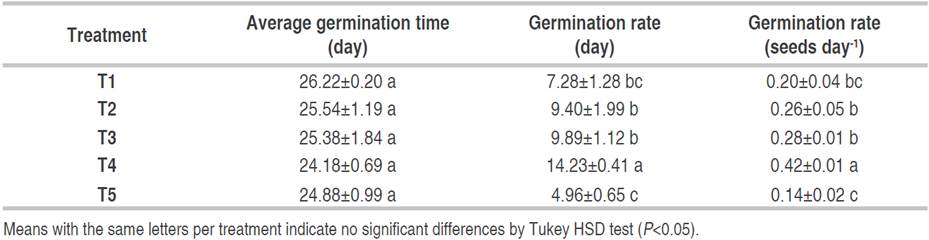

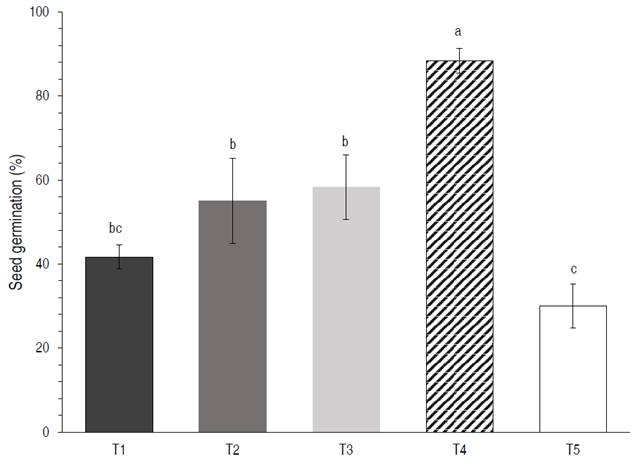

According to the analysis of variance, the type of substrate has a significant effect (P<0.05) on the total number of germinated seeds of C. pubescens. Tukey's post hoc test showed that T4 had the highest germination rate of 88.3±2.88%, followed by T3 and T2 with 58.3±2.88% and 55±10%, respectively, while T5 had the lowest germination rate of 30±5%. There were significant differences (P<0.05) between T2, T3 (germination >50%) and T1 and T5 (germination <50%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Effect of substrate on C. pubescens seed germination at 60 days. Means with the same letters per treatment indicate no significant differences by Tukey HSD test (P<0.05).

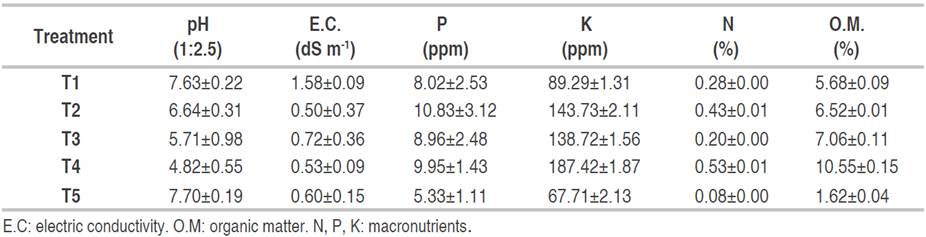

The highest germination rate (88.3%) of C. pubescens seeds was recorded at T4 (forest substrate), this result may be related to the high organic matter content (10.55%) and pH (4.82) of the substrate (García-Hoyos et al., 2011), in addition to the texture (sandy soil) which facilitates water retention and circulation, also provide the necessary nutrients during germination (Alfonso et al., 2017; Cunha et al., 2006). The type of substrate influences seed imbibition, due to a series of characteristics such as water potential (Wagner et al., 2006), which allows the activation of substances stored in the embryonic system and thus accelerates and increases their germination rate (García-Hoyos et al., 2011). The mean germination time of C. pubescens seeds was 24.18 to 26.22 days (T4 and T1, respectively). There were significant differences (P<0.05) in the speed and germination index of C. pubescens seeds. The highest germination index was recorded at T4, followed by T3 and T2. The germination speed in T4 was the highest and significant differences (P<0.05) were determined with the other treatments (Table 2). Table 3 shows the physicochemical characteristics of the substrates used in the germination of C. pubescens seeds; in the five treatments the texture was sandy loam.

Several studies have demonstrated the effect of substrate type on seed germination in species of the genus Cinchona, with some variation in results due to climatic, species, and pre-specified methodological factors. For example, Campos et al. (2016) on C. pubescens seeds with KNO3 at 1000 ppm achieved a germination rate of 91%, which is considered high compared to the rate found in this study (88.3%) and according to Conde et al. (2017), with 83.33% germination C. officinalis on peat substrates. Jäger (2014) showed that C. pubescens seeds have germination rates of 50 to 85%, which is the range that includes the results reported in this study. Rodríguez et al. (2020) reported 50% germination in sandy textured substrates, a value similar to T2 and T3 in this study. Jeréz (2017) found a germination rate of 70.67% for C. officinalis seeds treated with liquid mycorrhizae and in a substrate (20% black soil +60% pine bark +20% rice husk).

Higher germination rates and speed and shorter germination time were reported for C. pubescens seeds at T4, which favors sexual propagation of C. pubescens and avoids prolonged dormancy of seeds in the germinator that are often affected by pathogen invasion and consequently generate uneven seedling growth. There is no doubt that C. pubescens seeds require certain favorable conditions provided by the substrate, including organic matter content, water retention capacity, pH, and adequate amounts of macronutrients (Rodríguez et al., 2020).

CONCLUSIONS

It was found that the type of substrate used had a positive influence on the germination of C. pubescens seeds; in this sense, it is recommended to use forest soil extracted from areas where there are relicts of C. pubescens and avoid combining them with other substrates. Likewise, for the mass propagation of species of the genus Cinchona, it is not recommended to use pure sand as a substrate in the germination stage.