Brazil holds the world’s greatest diversity of caimans, with six known species (Costa and Bernils, 2018). Caimans are opportunistic predators, eating almost any capturable prey they find, sometimes even eating individuals of their respective own species (Magnusson, Da-Silva, and Lima, 1987; Piña, Larriera, and Cabrera, 2003; Santos et al, 1996). Caimans show an ontogenetic variation of diet, with young individuals preferring invertebrates and gradually incorporating vertebrates as they grow up (Ortiz, Charruau, and Reynoso, 2020). However, eating poisonous amphibians may be dangerous. For example, the population densities of Crocodylus johnstoni in Australia declined in almost 80% due to the invasive poisonous toad Rhinella marina (Letnic, Webb, and Shine, 2008). Amphibians are widely distributed, vary in size, and are potential prey for many vertebrate and invertebrate species (Duellman and Trueb, 1994). Most predatory events of anurans are reported during the reproductive season, where many animals gather together. Despite the importance of identifying the predators of amphibians, researchers have difficulties making observations of predation in nature (Pombal Jr., 2007). Toads of the family Bufonidae reproduce at the end of the cold and dry season, probably as a strategy for the tadpoles to develop during the wet season, when food is abundant (Oda, Bastos, and Lima, 2009; Santos, Rossa-Feres, and Casatti, 2007). Bufonids are considered “true toads” due to the presence of an agglomerate of poison glands on their body. Specifically, the individuals of R. diptycha have the parotid glands behind their eyes, and the paracnemic glands on their hind legs, as well as many other small poison gland clusters scattered throughout their bodies (Frost, 2009; Jared et al, 2009). These glands are a passive defense for the toad that releases the poison when the gland is pressed (Jared et al, 2009). The potential predator would pass from local irritation to even death in less than 15 minutes after the intoxication (Knowles, 1968; Micuda, 1968; Oehme, Brown, and Fowler, 1980; Otani, Palumbo, and Read 1969). The broad-snouted-caiman, Caiman latirostris, is one of the most widely distributed caimans of South America, being present from the northeast of Brazil, through Bolivia and Paraguay, to the northeast of Argentina and Uruguay (Verdade, Larriera, and Piña, 2010). Here we report the first event of an individual of C. latirostris feeding on R. diptycha.

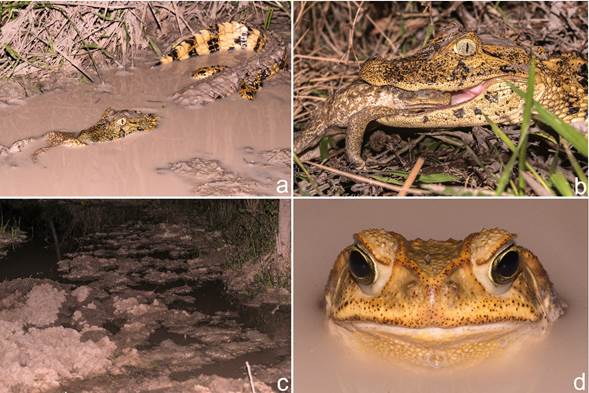

The event took place in September 2019, at 20:00 h, during a nighttime sampling of reptiles (SISBIO 64074), in a swamp (20°35'14.87"S y 51°21'29.73"W) at the municipality of Ilha Solteira, at the northwest of the state of São Paulo (Brazil). An individual of C. latirostris was detected by the reflection of the lantern’s light by its eyes. As we approached, we perceived that the individual was eating an adult male of R. diptycha, biting it through the left anterior region. The individual of C. latirostris was about 80 cm (total length), and thus considered a young individual (Verdade, 1995). The R. diptycha toad was an adult male, of approximately 15 cm long. The whole predatory event, from the death of the prey to its complete ingestion, took approximately 45 minutes. From the time we began the observation, the toad remained swollen for approximately one minute, until it died, with the caiman taking from the mouth, partially submerged (Figure 1a). Once the toad died, the caiman started moving its mouth, biting the prey until it managed to position it with the anterior part inside its mouth (Figure 1b). The caiman moved about, adjusting the toad with its mouth four or five times, and then standing still for about five minutes. We noticed that the caiman was breathing very quickly. When first spotted, the caiman was in a shallow pond with muddy water and clay (Figure 1c). Over the course of the observation, the individual moved about a meter in direction to the shore, due to interference by the flash of the photographic camera. Once the caiman ate the whole toad, without tearing parts or limbs, the crocodilian walked slowly to the marsh, where it remained at rest. When we finished the fieldwork, two hours later, we passed by the pond again to check for the presence of the individual. The caiman was still near the place, at rest. None of the animals were manipulated or collected, having as testimonial material the photographs, deposited in the Reference Zoological Collection ZUFMS (ZUFMS-AMP12942; ZUFMS-AMP12943 e ZUFMS-REP03457).

In general, anurans are part of the diet of several animal species. Animals eat poisonous amphibians by their posterior region to avoid contact with the poison (Haddad and Bastos, 1997; Loebmann, Solé, and Kwet, 2008; Toledo, 2003). Amongst vertebrates, some species are adapted to eat bufonid toads, as is the case of snakes of the genus Xenodon, which have a modified adaptation to pierce the toad’s lung and are little susceptible to its poison (Lavilla, Schrocchi, and Terán, 1979). Other animals, such as raccoons and otters, avoid intoxication by skinning the toad, taking the viscera out and avoiding ingestion of the dorsal skin (Morales, Ruiz-Olmo, Lizana, and Gutiérrez, 2016). The Australian rodent Hydromys chrysogastes avoids intoxication by making a small incision in the toad’s ventral area and only eating some internal organs (Parrott, Doody, McHenry, and Clulow, 2019). Similarly, some raptor birds eat the viscera and avoid eating the dorsal skin (Crozariol, and Gomes, 2009; Röhe, and Pinassi-Antunes, 2008,).

Figure 1 Predation of Rhinella diptycha by Caiman latirostris in a pond of Ilha Solteira (São Paulo, Brazil). A. The moment we spotted the predatory event; B. R. diptycha is positioned to be ingested by C. latirostris; C. The pond where the event was observed; D. An adult female of R. diptycha was found a few meters away from the predatory event.

Despite the different strategies used to eat bufonid toads, unsuccessful predation has been reported, such as an individual of Ceratophrys aurita, which ingested a specimen of R. diptycha and died within a day and a half after ingestion (Silva-Soares, Mônico, Ferreira, and De Castro, 2016). Records of predation and ingestion of poisonous amphibians are seldom reported in caimans. Among those reported, there are the predatory events of R. granulosa and R. marina by Caiman crocodiles crocodiles (Gorzula, 1978; Morato, Batista, and Paz, 2011); R. marina by Paleosuchus trigonatus (De Assis, and Dos Santos, 2007) and R. diptycha by P. palpebrosus (Toledo, Ribeiro, and Haddad, 2007). Although the presence of frogs in the diet of C. latirostris is already known, its actual frequency may be underestimated in the published literature due to the rapid digestion of this type of prey (Borteiro, Gutiérrez, Tedros, and Kolenc, 2009; Melo, 2002).

We think that the caiman might have been attracted to the prey by its vocalization, since we found a female R. diptycha nearby (Figure 1d). Even though mating vocalization has significant advantages for anurans to attract sexual mates, it increases exposition to predators (Toledo, 2003). This is the first record of C. latirostris predating upon a specimen of the poisonous anuran R. diptycha. Unlike the case of C. johnstoni, who died by eating introduced R. marina toads in Australia (Letnic et al, 2008), our register suggests the caiman was unaffected by the poisonous toad. This may be explained because R. diptycha is a native species, probably coexisting for millions of years with C. latirostris at the study area. We recommend future research confirming the potential tolerance of C. latirostris to R. diptycha’s poisson and assessing the causes and mechanisms that make it possible.